Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

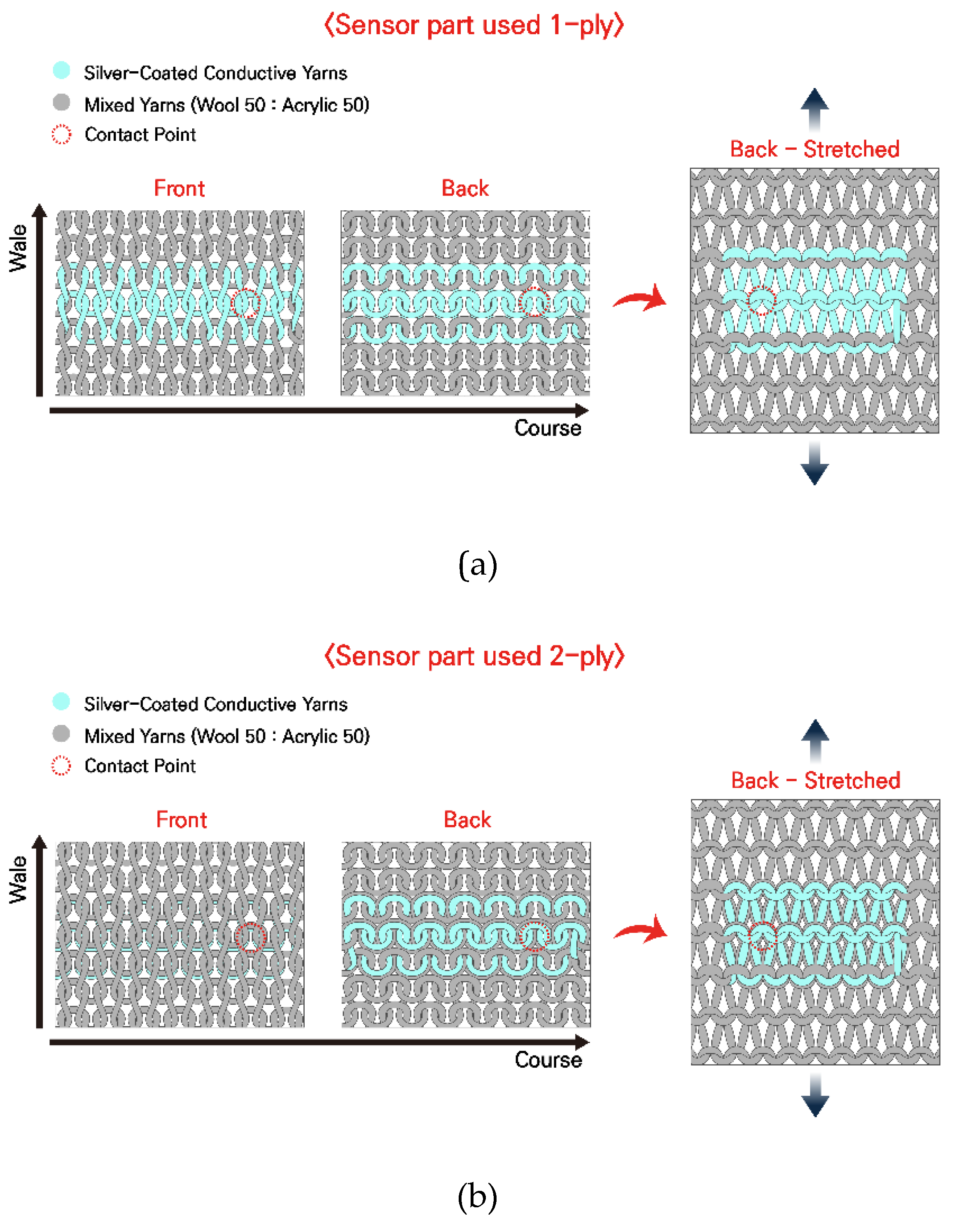

2.1. Structure and Working Mechanism

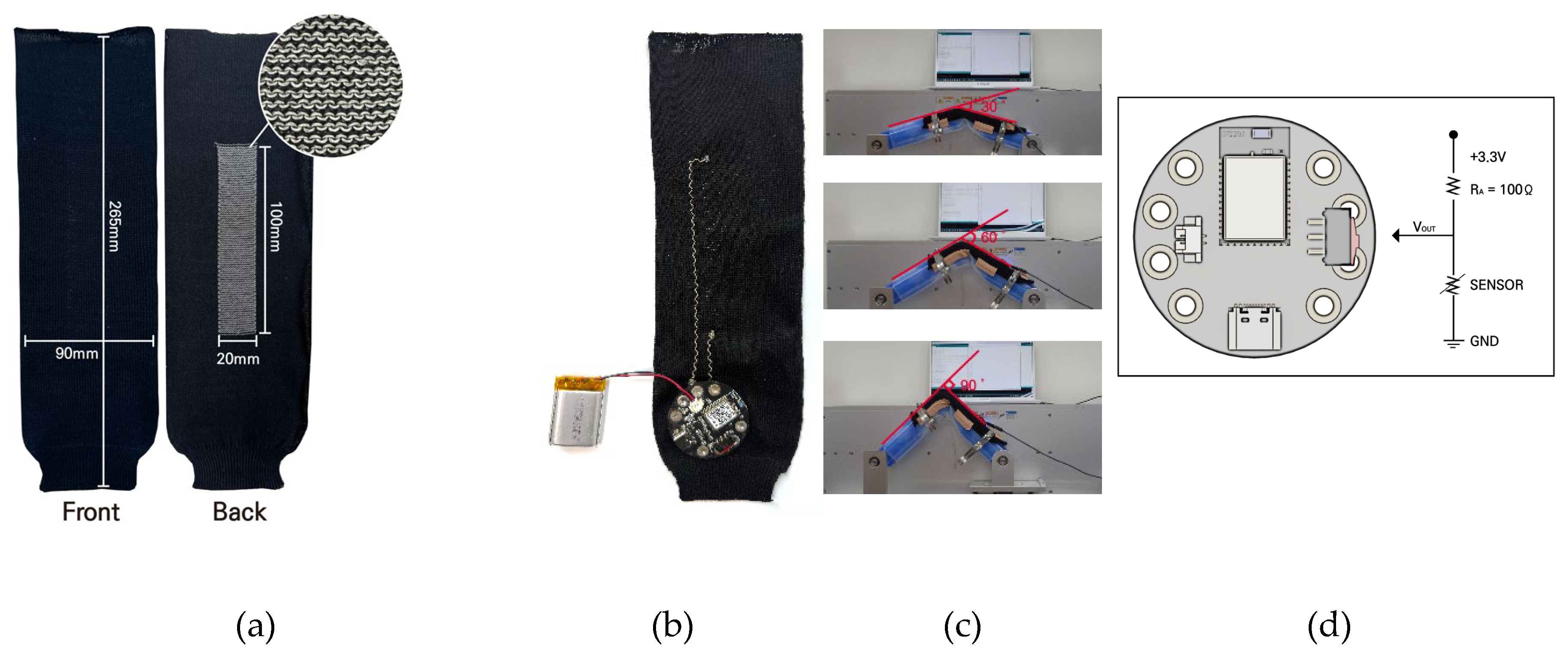

2.2. Measurement of Electromechanical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

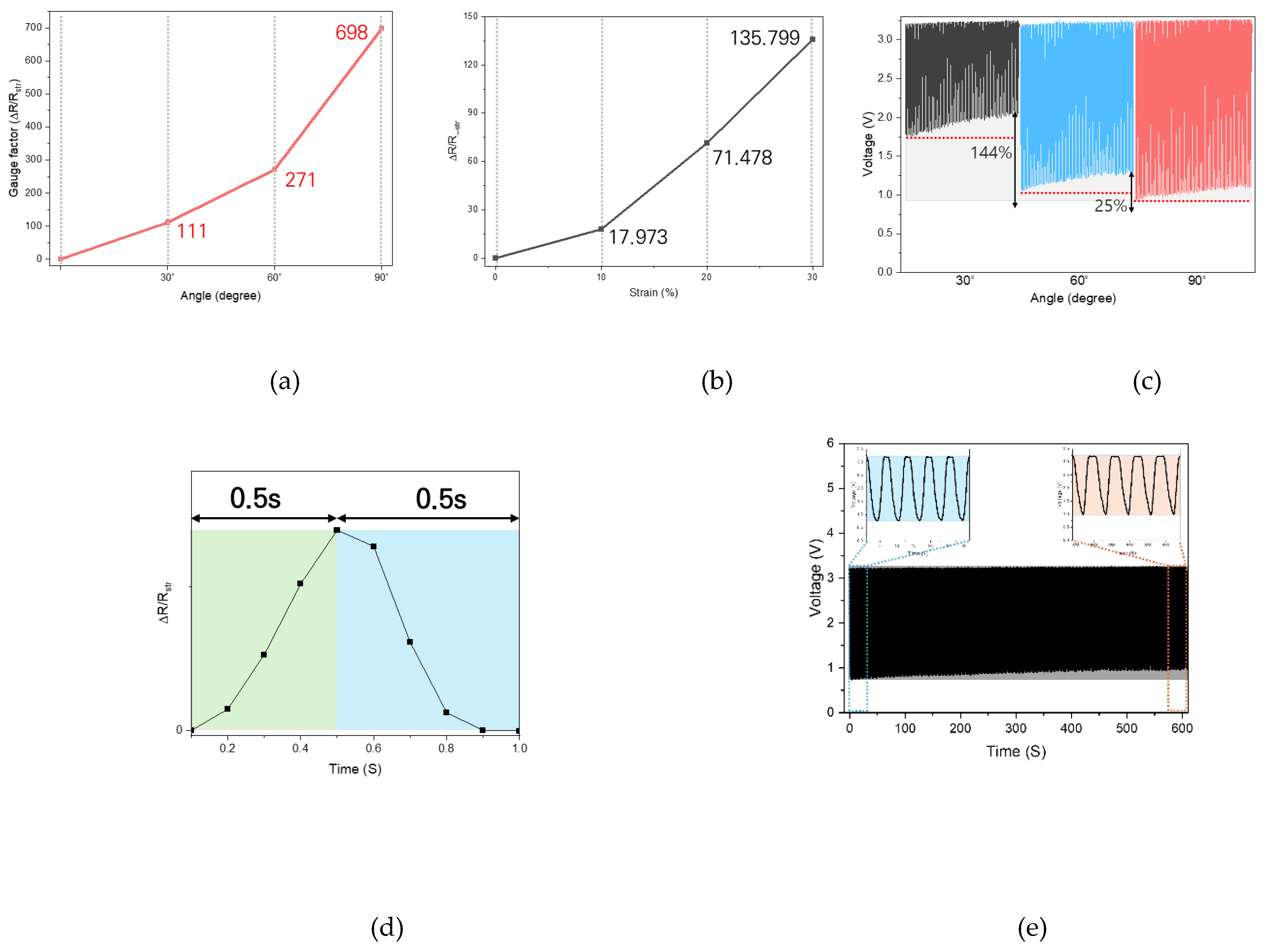

3.1. Results of Repeated Bending Experiments

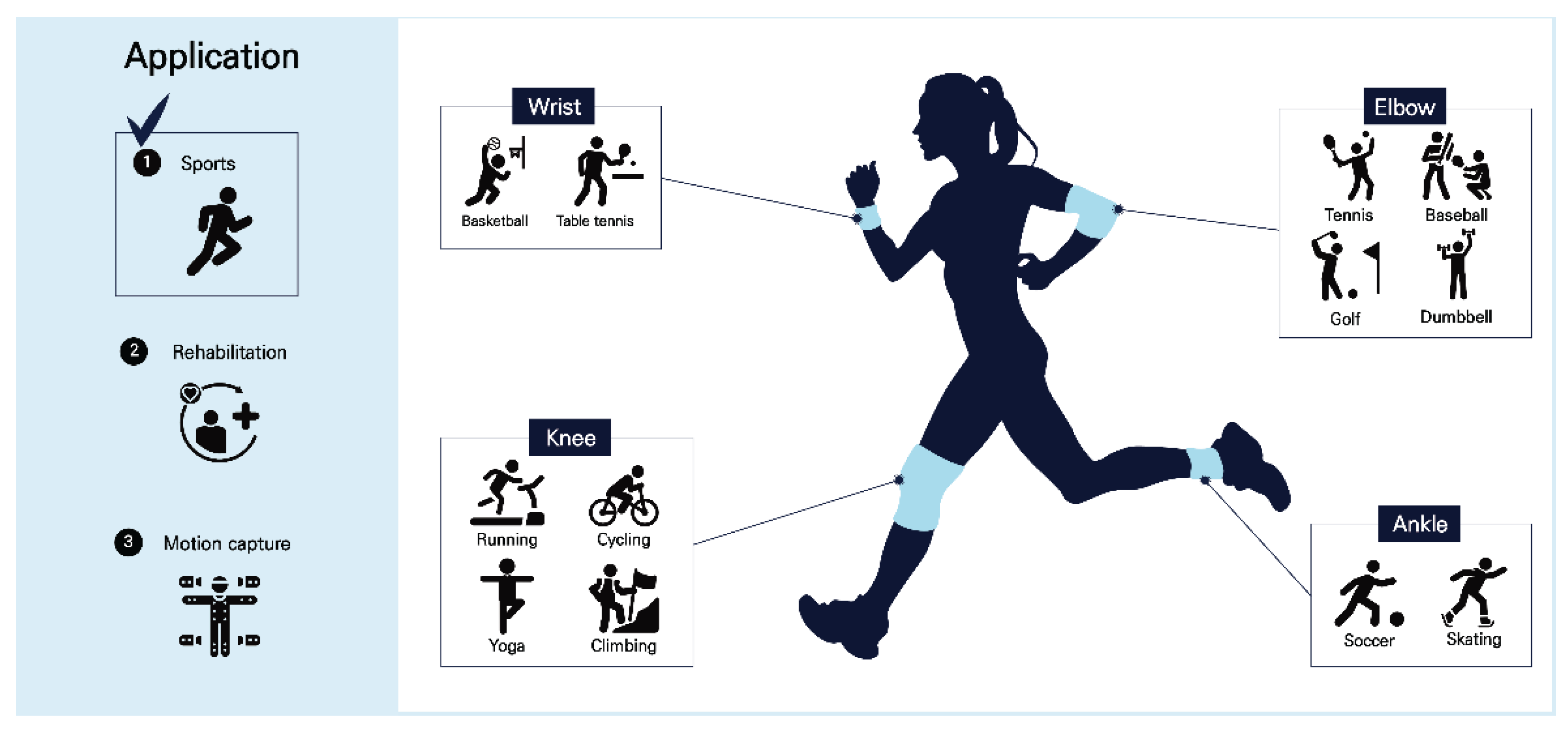

3.2. Applications of Knitted Strain Sensors

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alam, T.; Saidane, F.; Faisal, A. A.; Khan, A.; Hossain, G. Smart-textile strain sensor for human joint monitoring. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical: 2022, 341, 113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, H.; Banerjee, H.; Jusufi, A.; Strokes, A. A; Park, I.; Sitti, M.; Amjadi, M. Wearable and Stretchable Strain Sensors: Materials, Sensing Mechanisms, and Applications. Advanced Intelligent System: 2020, 2, 2000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, R. K.; Miao, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, y.; Wan, A.; Boakye, A. Knitted piezoresistive strain sensor performance, impact of conductive area and profile design. Journal of Industrial Textiles: 2020, 50, 616–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Lee, J.; Qiao, S.; Ghaffari, R.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Song, C.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.; Jun, S. W.; et al. Multifunctional wearable devices for diagnosis and therapy of movement disorders. Nature nanotechnology: 2014, 9, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozali, B.; Ghodrat, S.; Jansen, K. M. Design of Wearable Finger Sensors for Rehabilitation Applications. Micromachines: 2023, 4, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Soltanian, S.; Servati, P.; Ko, F.; Weng, M. A knitted wearable flexible sensor for monitoring breathing condition. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics: 2020, 15. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, J.; Cong, H. Design and performance of stretchable resistive sensor based on knitted loop structures for motion detection. Journal of Industrial Textiles: 2023, 53. [CrossRef]

- Morinaga Sports Fitness. (Effective) Dumbbell Exercise Guide. Seoul: Udumji; 2005. Korean.

- Seyedin, S.; Razal, J. M.; Innis, P. C.; Jeiranikhameneh, A.; Beirne, S.; Wallace, G. G. Knitted strain sensor textiles of highly conductive all-polymeric fibers. ACS applied materials & interfaces: 2015, 7, 21150–21158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, O.; Kennon, W. R.; Husain, M. D. Textile-based weft knitted strain sensors: Effect of fabric parameters on sensor properties. Sensors: 2013, 13, 11114–11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Jia, Y.; Miao, M. High sensitivity knitted fabric bi-directional pressure sensor based on conductive blended yarn. Smart Materials and Structures: 2019, 28, 035017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M. A.; Cay, G.; Ravichandran, V.; Altekreeti, A. ; Gitelson-Kahn A; Constant, N. ; Solanki, D.; Mankodiya, K. Textile knitted stretch sensors for wearable health monitoring: Design and performance evaluation. Biosensors: 2022, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liao, S.; Wei, Q.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Q. Comparative study of different carbon materials for the preparation of knitted fabric sensors. Cellulose: 2022, 29, 7431–7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jun, J.; Oh, Y.; Choi, H.; Lee, M.; Min, K.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Nam, H.; Singh, S.; et al. Assessing the Role of Yarn Placement in Plated Knit Strain Sensors: A Detailed Study of Their Electromechanical Properties and Applicability in Bending Cycle Monitoring. Sensors: 2024, 24, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liang, X.; Wan, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, G.; Dong, Z.; Chen, C.; Cong, H.; He, H. A Review on Knitted Flexible Strain Sensors for Human Activity Monitoring. Advanced Materials Technologies: 2023, 8, 2300820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jun, J.; Oh, Y.; Choi, H.; Lee, M.; Min, K.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Nam, H.; Singh, S.; et al. Assessing the Role of Yarn Placement in Plated Knit Strain Sensors: A Detailed Study of Their Electromechanical Properties and Applicability in Bending Cycle Monitoring. Sensors: 2024, 24, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.; Lee, S. Durability Evaluation of Stainless Steel Conductive Yarn under Various Sewing Method by Repeated Strain and Abrasion Test. Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles: 2018, 42, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaga Sports Fitness. (Effective) Dumbbell Exercise Guide. Seoul: Udumji; 2005. Korean.

- Morinaga Sports Fitness. (Effective) Dumbbell Exercise Guide. Seoul: Udumji; 2005. Korean.

- Kim, S. A Smart Glove Study that Performs Language Translation by Pattern Recognition by Applying Strain Sensors. Master’s degree, Hanyang University, Seoul, 2023 Feb.

- Roh, J. Wearable Textile Strain Sensors. Fashion & Textile Research Journal: 2016, 18, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, O.; Kennon, W. R; Husain, M.D. Textile-based weft knitted strain sensors: Effect of fabric parameters on sensor properties. Sensors: 2013, 13, 11114–11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. Programming Noise Filtering System for E-Band Textile Strain Sensor. Master’s degree, Soongsil University, Seoul, 2023 Feb.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).