1. Introduction

The discrete Fourier transform (DFT) is an orthogonal transform [

1] which, for the case of N input/output samples, may be expressed in normalized form via the equation

where the input/output data vectors belong to C

N, the linear space of complex-valued N-tuples, and the transform kernel is expressed in terms of powers of W

N, where

the primitive N

th complex root of unity [

3,

15]. Fast solutions to the DFT are referred to generically as fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithms [4-6] and, when the transform length is expressible as some power of a fixed integer R – whereby the algorithm is referred to as a

fixed-radix FFT with

radix R – enable the associated arithmetic complexity to be reduced from

to just

.

The complex-valued exponential terms, , appearing in Eqtn. 1, each comprise two trigonometric components – with each pair being more commonly referred to as twiddle factors [4-6] – that are required to be fed to each instance of the FFT’s butterfly, this being the computational engine used for carrying out the algorithm’s repetitive arithmetic operations and which, for a radix-R transform, produces R complex-valued outputs from R complex-valued inputs.

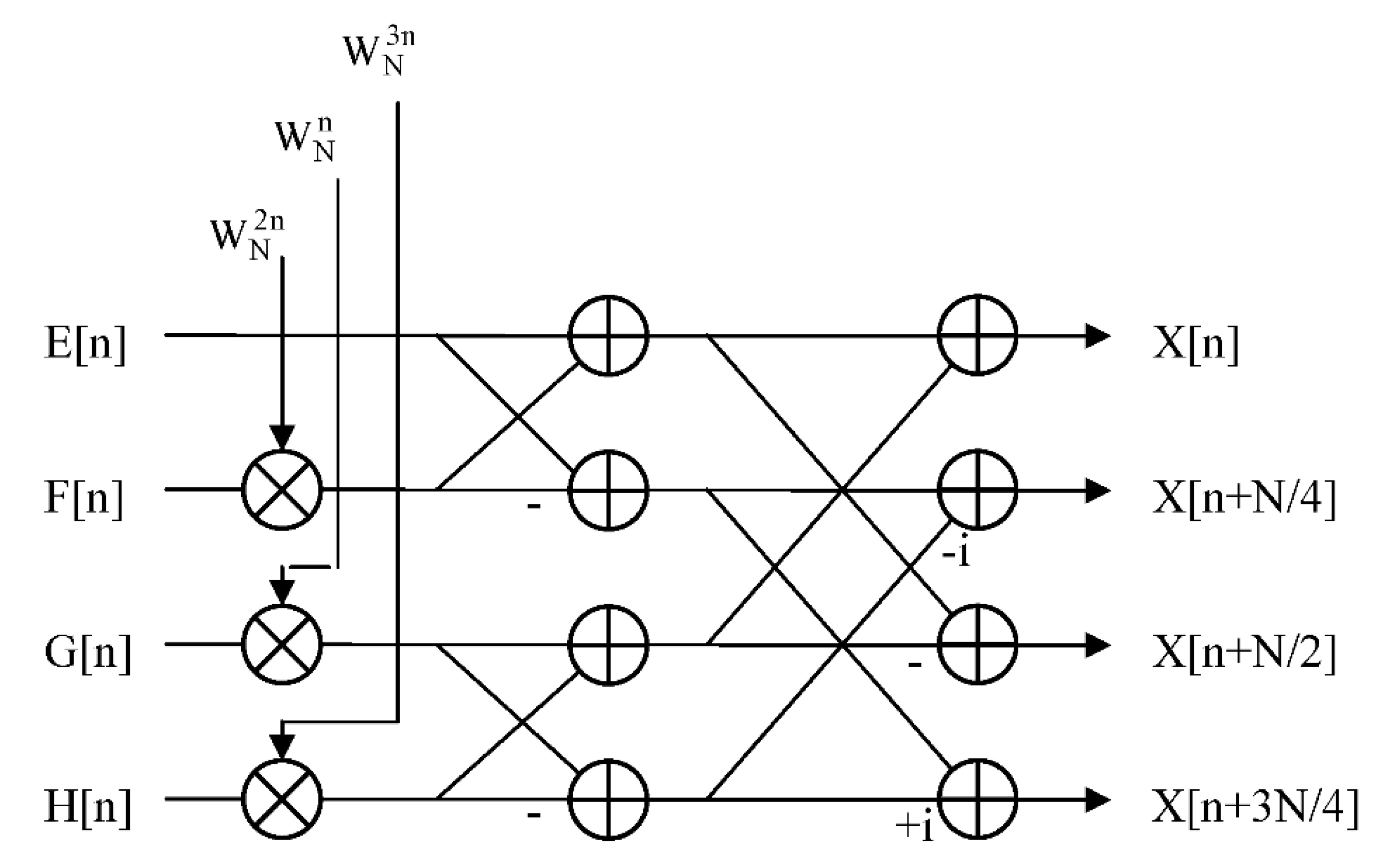

The twiddle factor requirement, more exactly, is that for a radix-R FFT algorithm there will be R-1 non-trivial twiddle factors to be applied to each butterfly. For a decimation-in-time (DIT) type FFT design [4-6], with typically digit-reverse (DR) -ordered inputs and naturally (NAT) -ordered outputs, the twiddle factors are applied to the butterfly inputs – see

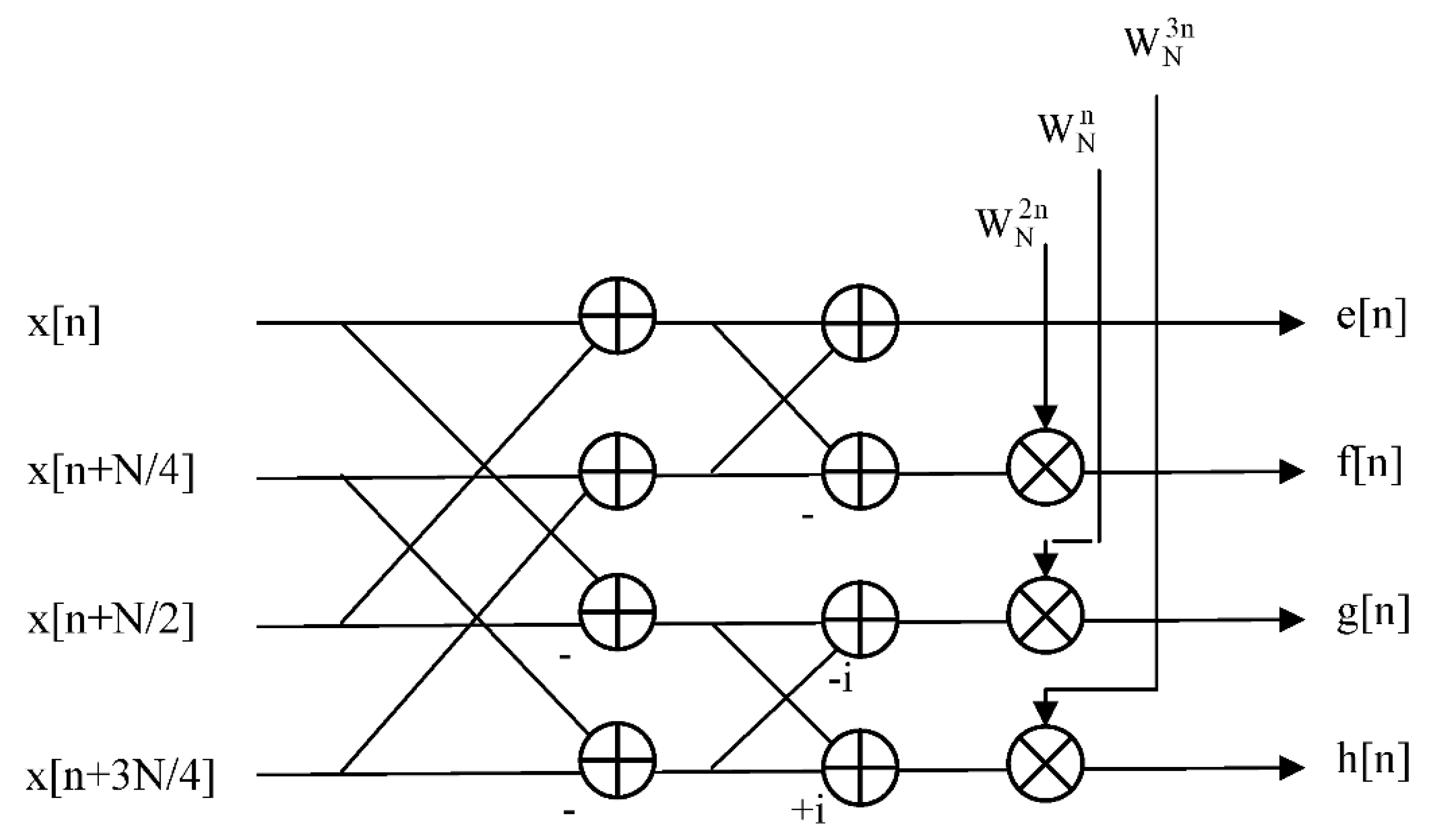

Figure 1, whilst for a decimation-in-frequency (DIF) type FFT design [4-6], with typically NAT-ordered inputs and DR-ordered outputs, the twiddle factors are applied to the butterfly outputs – see

Figure 2. Each twiddle factor, as stated above, possesses two components, one being defined by the sine function and the other by the cosine function, which may be retrieved directly from the

coefficient memory or generated

on-the-fly in order to be able to carry out the necessary processing for the FFT butterfly.

Note that the DR-ordered and NAT-ordered index mappings referred to above may each be applied to either the input or output data sets for both the DIT and DIF variations of the fixed-radix FFT, yielding a total of four possible combinations for any fixed-radix transform: namely, DIT

NR, DIT

RN, DIF

NR and DIF

RN where ‘N’ refers to the NAT-ordered mapping and ‘R’ to the DR-ordered mapping and where the first letter of each pair corresponds to the input data mapping and the second letter to the output data mapping [

5]. The DIT

RN and DIF

NR radix-4 butterflies correspond to those already illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively, from which one can easily visualize how the designs may be straightforwardly generalized to higher radices. For the case of an arbitrary radix-R DIT algorithm, for example, the twiddle factors will be applied to all but one of the R butterfly inputs, whereas with the corresponding DIF algorithm, the twiddle factors will be applied to all but one of the R butterfly outputs.

When the DFT is viewed as a matrix operator, Eqtn. 1 becomes a matrix-vector product, with the effect of the radix-R FFT being to factorize the N×N DFT matrix into a product of logRN sparse matrices, with each sparse matrix being of size N×N and comprising N/R sub-matrices, each of size R×R, where each sub-matrix corresponds in turn to the operation of a radix-R butterfly. Thus, each sparse matrix factor produces N partial-DFT outputs though the execution of N/R radix-R butterflies. The effect of such a factorization is thus to reduce the computation of the original length-N transform to the execution of logRN computational stages, with each stage comprising radix-R butterflies, where the execution of a given stage can only commence once that of its predecessor has been completed, and with the FFT output being produced on completion of the final computational stage. Thus, from this analysis, it is evident that the computational efficiency of the fixed-radix FFT is totally dependent upon the computational efficiency of the individual butterfly.

Also, an efficient parallel implementation of the fixed-radix FFT – particularly for the processing of long (of order one million samples, as might be encountered with the processing of wideband signals embedded in astronomical data) to ultra-long (of order one billion samples, as might be encountered with the processing of ultra-wideband signals embedded in cosmic microwave data) data sets [

13] – invariably requires an efficient parallel mechanism for the generation or computation of the twiddle factors (unless the DFT is solved by approximate means via the adoption of a suitably defined sparse FFT algorithm [

8,

11]) as it is essential that the full set of R-1 non-trivial terms required by each radix-R butterfly – whether applied to the inputs or the outputs – should be available simultaneously in order to avoid potential timing issues and delays and to be produced at a rate that is consistent with the processing rate of the FFT.

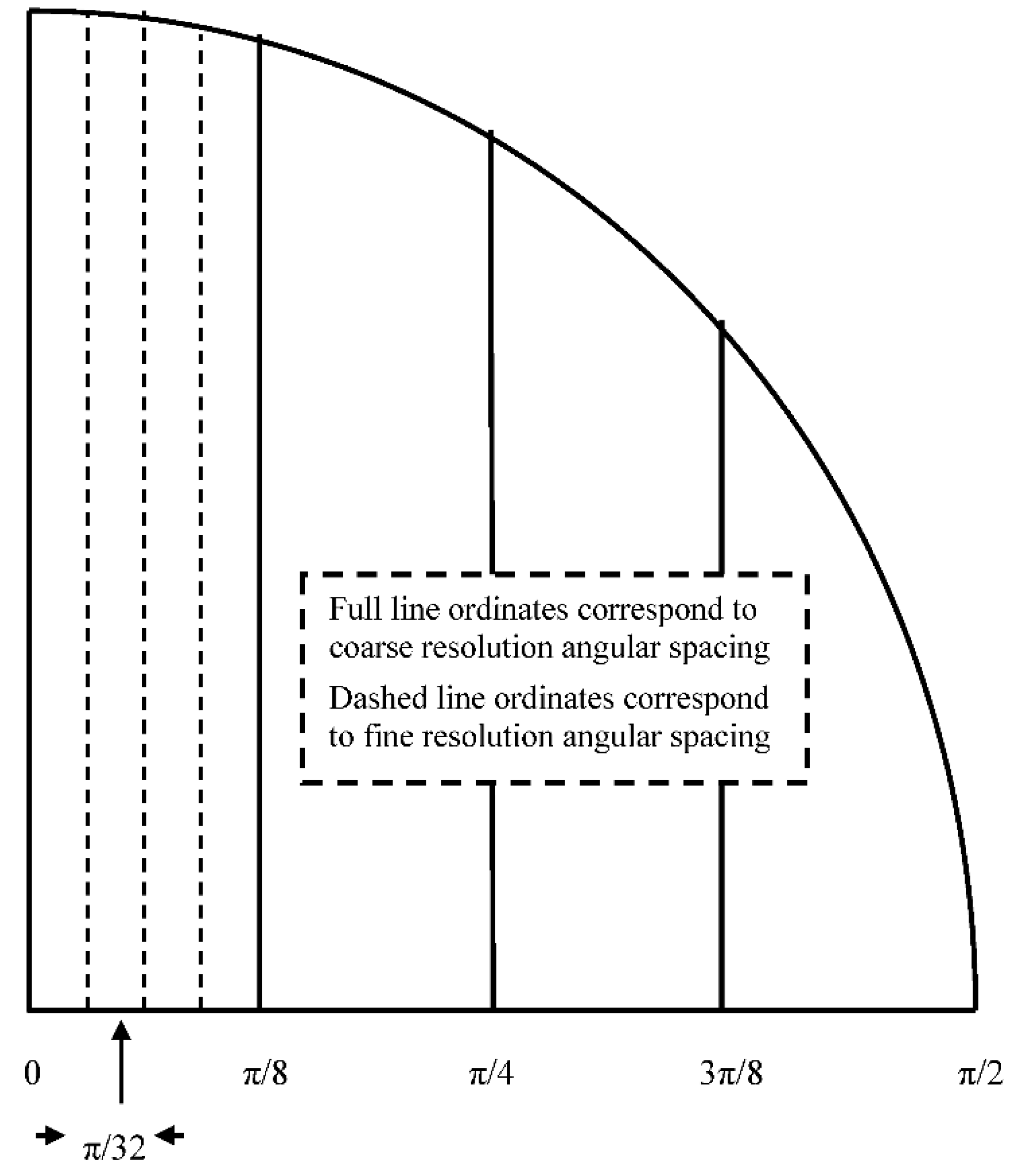

The computational efficiency of the twiddle factor generation for the fixed-radix FFT may be optimized by trading off the arithmetic component of the resource requirement against the memory component through the combined use of appropriately defined look-up tables (LUTs) – which may be of either single-level (comprising a single LUT with a fixed angular resolution) or multi-level (comprising multiple single-level LUTs each with its own distinct fixed angular resolution) type [

10,

12] – and trigonometric identities. Although the FFT radix can actually take on any integer value, the most commonly used radices are those of two and four, primarily for the resulting flexibility (generating a large number of possible transform sizes for various possible applications) that they offer and for ease of implementation. The attraction of choosing a solution based upon the radix-4 factorization, rather than that of the more familiar radix-2, is that of its greater computational efficiency – in terms of both a reduced arithmetic requirement (that is, of the required numbers of multiplications and additions) and reduced number of memory accesses (four complex-valued samples at a time instead of just two – comprising both real and imaginary components) for the retrieval of data from memory.

There is, in turn, the potential for exploiting greater parallelism, at the arithmetic level, via the use of a larger sized butterfly, thereby offering the possibility of achieving a higher

computational density (that is, throughput per unit area of silicon [

9]) when implemented in silicon with a suitably chosen computing device and architecture. As a result, we will be particularly concerned with the radix-4 version of the FFT algorithm, together with the two-level version of the LUT, as these two algorithmic choices facilitate ease of illustration and offer the potential for flexible computationally-efficient FFT designs.

Thus, following this introductory section, complexity considerations for both sequential and parallel computing devices are discussed in

Section 2, followed by the derivation of a collection of formulae in

Section 3 for some of the standard trigonometric identities which, together with suitably defined LUTs – dealing with both single-level and multi-level types – as discussed in

Section 4, will be required for the efficient computation of the twiddle factors.

Section 5 then describes, in some detail, two different parallel computing solutions to the task of twiddle factor computation where the computation of each twiddle factor is assigned its own processing element (PE). The first scheme is based upon the adoption of the

single- instruction multiple-data (SIMD) technique [

2], as applied in the

spatial domain, whereby the PEs operate independently upon their own individual LUTs and may thus be executed simultaneously, whilst the second scheme is based upon the adoption of the

pipelining technique [

2], as applied in the

temporal domain, whereby the operation of all but the first LUT-based PE is based upon second-order recursion using previously computed PE outputs. Detailed examples for these two approaches are provided using a radix-4 butterfly combined with two-level LUTs and a brief comparative analysis provided in terms of both the

space-complexity, as expressed in terms of their relative arithmetic and memory components, and the

time-complexity, as expressed in terms of their associated latencies and throughputs, for a silicon-based hardware implementation. Finally, a brief summary and conclusions is provided in

Section 6.

2. Complexity Considerations

When dealing with questions of complexity relating to the twiddle factor computations for the case of a

sequential single-processor computing device, as is the case in

Section 3 and

Section 4, the memory requirement is to be denoted by C

MEM, with the associated arithmetic complexity being referred to via the required

number of arithmetic operations, as expressed in terms of the number of multiplications, denoted C

MPY, and the number of additions/subtractions, denoted C

ADD. When dealing with a silicon-based hardware implementation, however, on a suitably chosen

parallel computing device – as might typically be made available with field- programmable gate array (FPGA) technology [

14] – the complexity is to be defined in terms of the space-complexity and time-complexity. These parallel computing aspects, as will be discussed in some detail in

Section 5, will be the main focus of our interest

The space-complexity comprises: 1) the memory component, denoted RMEM, (and which is the same as CMEM when expressed in ‘words’) which represents the amount of random access memory (RAM) needed for construction of the LUTs; and 2) the arithmetic component, which consists of the number of arithmetic operators, as expressed in terms of the number of hardware multipliers, denoted RMPY, and the number of hardware adders, denoted RADD, assigned to the computational task. Note also, that with the adoption of fixed-point arithmetic, multiplication by any power of two equates to that of a simple left-shift operation, with multiplication by two thereby equating to that of a left-shift operation of length just one. The associated time-complexity will be represented by means of the latency, which is the elapsed time between the initial accesses of trigonometric data from an LUT to the production of the corresponding twiddle factor, and the throughput rate, which is the number of twiddle factors that can be produced in a given period of time (typically taken to be a clock cycle, which is the rate at which the target computing device operates).

5. Parallel Computation of Twiddle Factors

Two parallel schemes, together with architectures, are now described for the computation of the twiddle factors for the radix-4 FFT butterfly, assuming the adoption of a suitably chosen parallel computing device. The space-complexity is first discussed, whereby one is able to optimize the resource utilization by trading off the memory component against the arithmetic component. The time-complexity is also discussed, this relating to how the two approaches may differ in terms of latency, due to possible timing delays, and throughput, due to possible differences in the computational needs of their respective PEs. The requirement, for a fully parallel implementation of the radix-4 FFT, is that all the twiddle factors are to be made simultaneously available for input to each instance of the radix-4 butterfly, thereby preventing potential timing delays and enabling the associated butterfly and its FFT to achieve and maintain real-time operation.

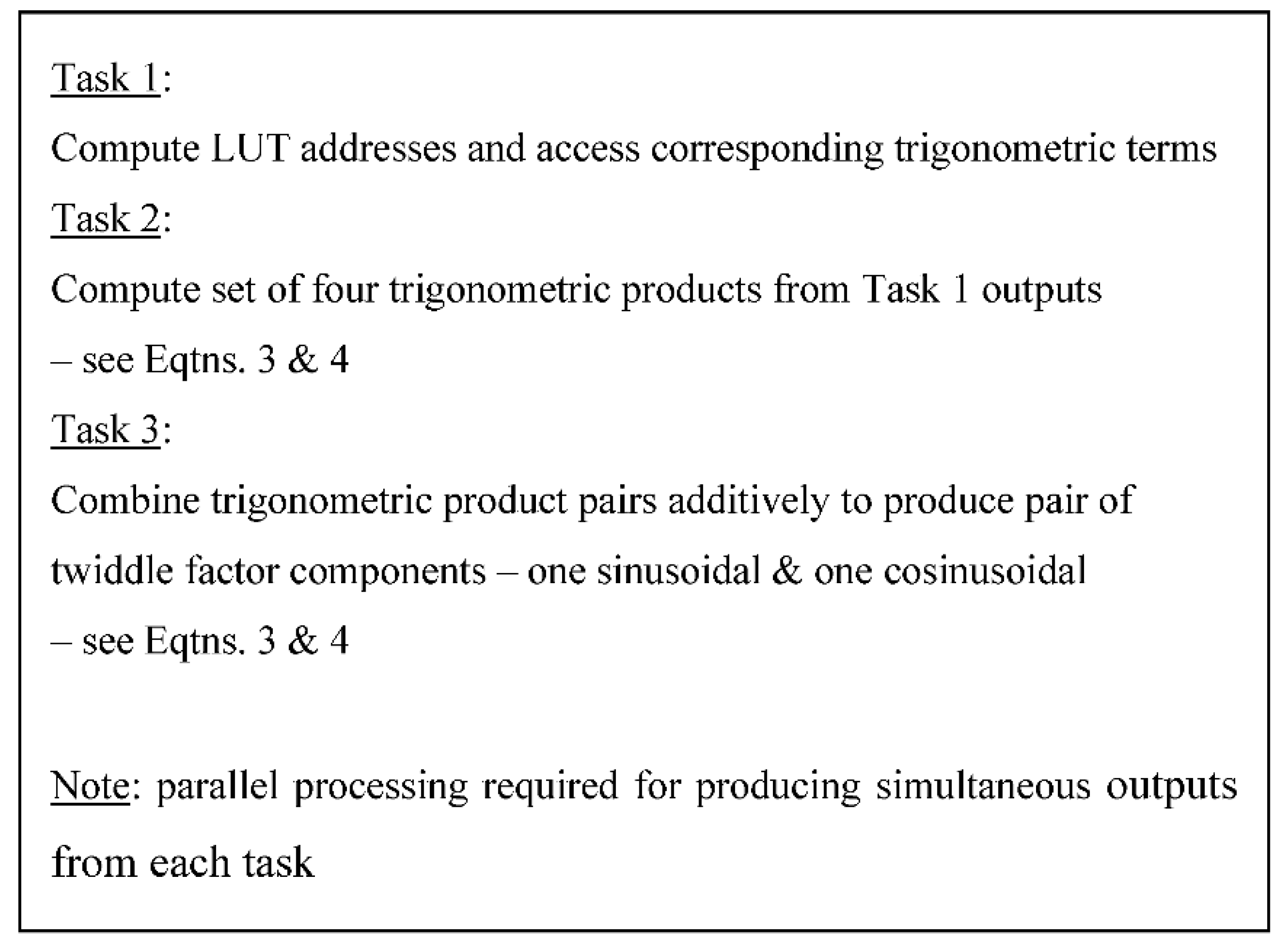

There are two computational domains where parallelism may be exploited: namely, the temporal domain and the spatial domain. The first of the two proposed schemes is based upon the adoption of the SIMD technique, as applied in the spatial domain, whilst the second is based upon the adoption of the pipelining technique, as applied in the temporal domain. Both approaches use one or more two-level LUTs, where the contents of a given LUT are combined in an appropriate fashion via the standard two-angle identities of Eqtns. 3 and 4 – as illustrated in

Figure 4.

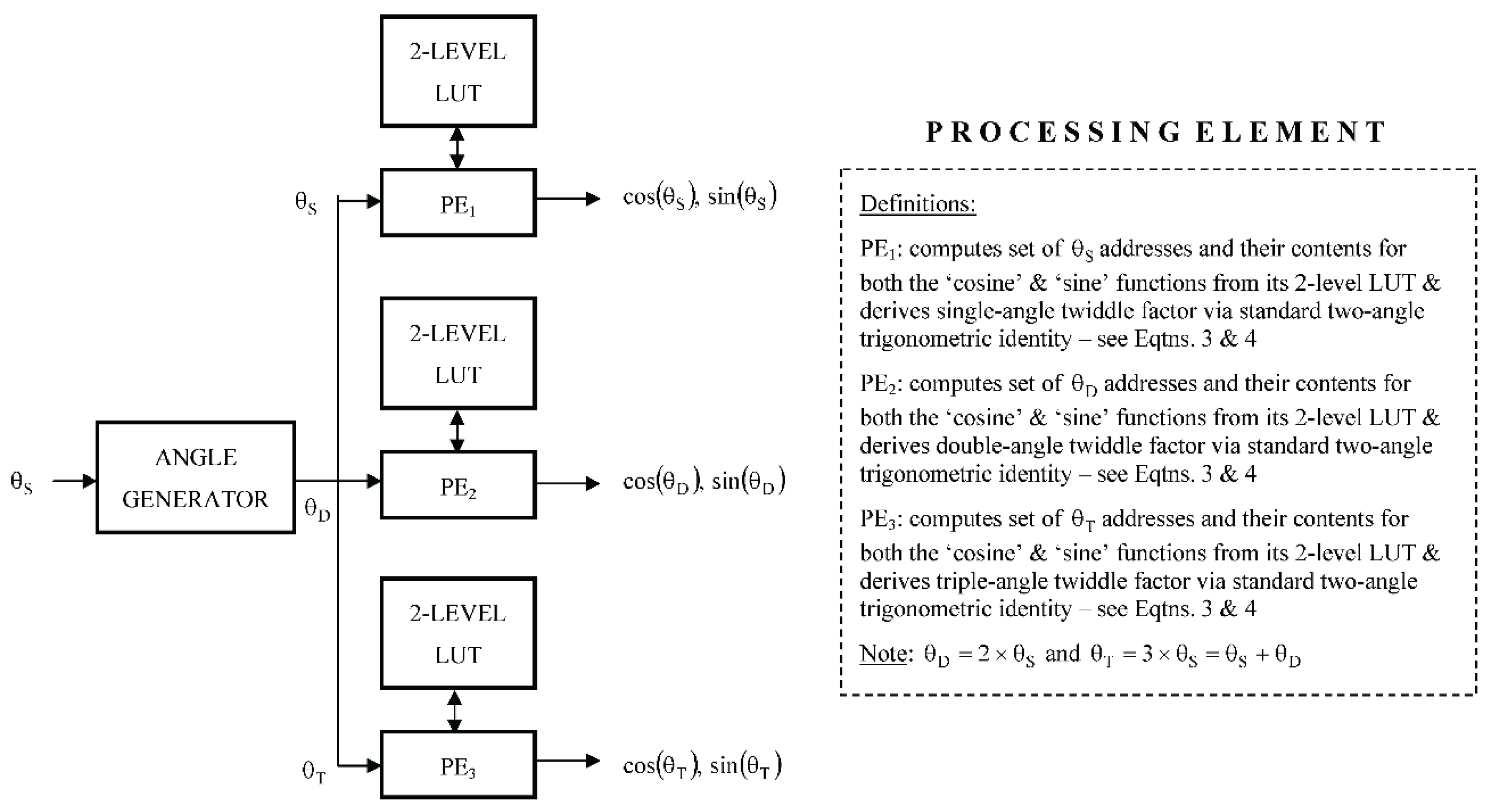

5.1. SIMD Approach with Multiple LUTs

With the SIMD approach, the computation of each non-trivial twiddle factor is assigned its own PE which has access, in turn, to its own individual two-level LUT, as illustrated in

Figure 5, thereby enabling each PE to produce a twiddle factor via the application of the standard two-angle identities of Eqtns. 3 and 4. As the parallelism is defined in the spatial domain, all three PEs may operate independently, being thus able to produce all three non-trivial twiddle factors simultaneously – noting that the other remaining twiddle factor is trivial with a fixed value of one. As a result, all the non-trivial twiddle factors are available for input to the radix-4 butterfly at the same time.

By denoting by

the logic-based function that converts a pair of angles,

and

, to the required set of addresses for accessing the two-level LUT, the initial operation of the PEs may be defined in the following way:

where addresses m

1 and m

2 both access the coarse-resolution LUT, whilst addresses n

1 and n

2 each accesses its own fine-resolution LUT. The subscripts/superscripts ‘S’, ‘D’ and ‘T’ refer to the angles used by the single-angle, double-angle and triple-angle twiddle factors, respectively.

These addresses, together with the coarse-resolution LUT, denoted

, and the two fine-resolution LUTs, denoted

and

, now enable the subsequent operation of the PEs to be defined in the following way:

so that, for a fully-parallel silicon-based hardware implementation, the execution of all three PEs require a total of: 1) 12 adders plus logic for setting up the three sets of LUT addresses, plus 2) 12 multipliers and six adders for the subsequent derivation of the twiddle factors, together with 3) three two-level LUTs, each two-level LUT comprising three single-level LUTs, each of length

for the case of a length-N transform.

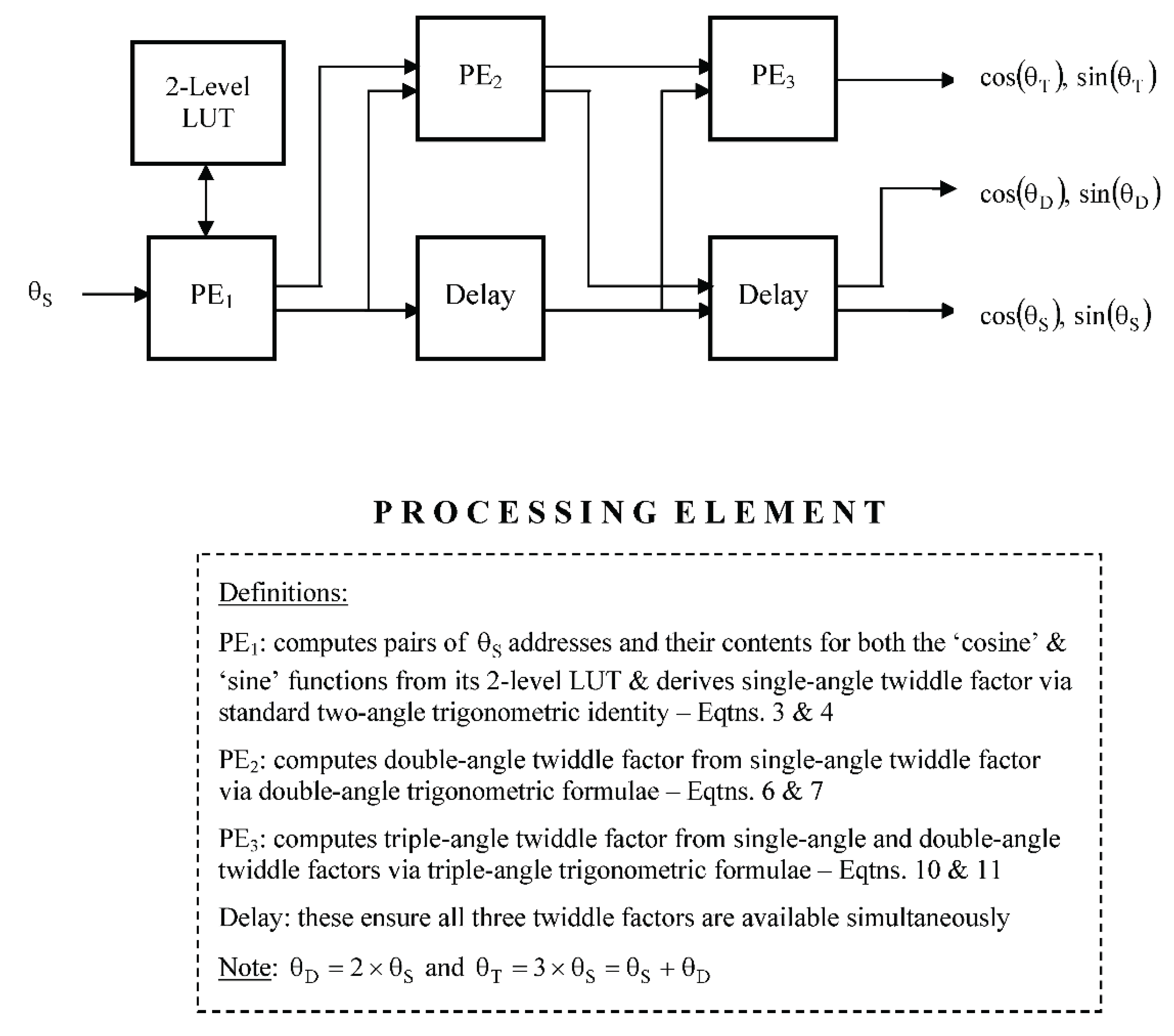

5.2. Pipelined Approach with One LUT + Recursion

With the pipelined approach, each non-trivial twiddle factor is again computed with its own PE, but whereas the first PE has access to its own individual two-level PE, the remaining two PEs each produce a twiddle factor in a

recursive manner from the previously computed twiddle factors, as illustrated in

Figure 6, via the application of the multi-angle formulae of Eqtns. 6 and 7 for the second non-trivial twiddle factor and Eqtns. 10 and 11 for the third non-trivial twiddle factor – these equations being particular cases of those expressed generically via Eqtns. 13 and 14. As the parallelism is defined in the temporal domain, the processing within each PE relies on the outputs produced by its predecessors, with the processing for a given PE being only able to commence once that of its predecessor has been completed. As a result, timing delays are required to ensure that all the non-trivial twiddle factors become available for input to the radix-4 butterfly at the same time – noting that the other remaining twiddle is trivial with a fixed value of one.

By denoting by

the logic-based function that converts a pair of angles,

and

, to the required set of addresses for accessing the two-level LUT, the initial operation of the first PE may be defined in the following way:

and its subsequent operation as

The twiddle factor outputs from the remaining PEs are derived in a recursive manner from previously computed twiddle factors, so that if

they may be defined in the following way:

so that, for a fully-parallel silicon-based hardware implementation, the execution of all three PEs require a total of: 1) four adders plus logic for setting up the set of LUT addresses, plus 2) eight multipliers (four of which – as required for PE

2 and PE

3 – are followed by a left-shift operation of length one) and five adders for the subsequent derivation of the twiddle factors, together with 3) one two-level LUT, comprising three single-level LUTs, each of length

for the case of a length-N transform.

5.3. Comparison of Resource Requirements

Firstly, from

Section 5.1, the total space-complexity for the twiddle factor computation via the SIMD-based solution may be expressed in terms of its arithmetic and memory components, denoted T

A and T

M, respectively, where

together with a small amount of logic for the address generation, and

words, for the case of a length-N transform.

Secondly, from

Section 5.2, the total space-complexity for the twiddle factor computation via the pipelined solution may also be expressed in terms of its arithmetic and memory components, denoted T

A and T

M, respectively, where

together with four trivial left-shift operations, each of length one, and a small amount of additional logic for the address generation, and

words, for the case of a length-N transform.

Assuming a silicon-based hardware implementation with a suitably chosen FPGA-based parallel computing device, the arithmetic component of the space-complexity of each solution will be dominated by the number of multipliers, given that for fixed-point arithmetic and with a word-length of W, the complexity of a multiplier will involve O(W2) slices of programmable logic whereas an adder will involve just O(W) such slices. As a result, the arithmetic component of the space-complexity for the pipelined solution is approximately two-thirds that of the SIMD-based solution, whilst its memory component is just one-third that of the SIMD-based solution, making the pipelined solution the more resource-efficient – and thus able to achieve a higher computational density – of the two studied solutions and particularly attractive, due to the low memory component, for those big-data memory-intensive applications involving the use of long to ultra-long FFTs.

Note that with both solutions, whilst the adders may be implemented very simply in programmable logic, optimal arithmetic efficiency will be obtained when the multiplications are carried out using the fast embedded multipliers as provided by the equipment manufacturer.

5.4. Discussion

To address the question of time-complexity for the two studied solutions, note firstly that the implementation of each LUT-based PE, as is evident from Eqtns. 36 to 41, involves the operation of four multipliers, which may be carried out in parallel, followed by the operation of two adders, which may also be carried out in parallel. For the remaining PEs, the twiddle factors are produced from previously computed twiddle factors in a recursive manner, so that the implementation of each such PE, as is evident from Eqtns. 47 to 50, involves the operation of just two multipliers, which may be carried out in parallel, followed by the operation of two adders, which may also be carried out in parallel. As a result, with simple internal pipelining for the implementation of the multipliers and adders, the computation for each type of PE would possess comparable latency with each PE able to produce a new twiddle factor every clock cycle. Therefore, with each type of solution, whether of SIMD or pipelined type, the set of three PEs could produce a new set of non-trivial twiddle factors every clock cycle and would thereby be consistent with the throughput rate of the associated butterfly – assuming the butterfly to be also implemented in a fully-parallel fashion using SIMD and/or pipelining techniques – thereby enabling the associated butterfly and its FFT to achieve and maintain real-time operation.

Thus, assuming the latency of each internally-pipelined PE to be one time step – expressible itself as a fixed number of clock cycles – then the only difference in time-complexity between parallel implementations of the radix-4 FFT, using the two types of twiddle factor computation schemes discussed, is that the pipelined solution requires an additional two time steps to account for the initial start-up delay due to the internal pipelining of PE2 and PE3.

Finally, note that although we have discussed the particular case of the radix-4 butterfly and its associated twiddle factors, the results generalize in a straightforward manner to the case of a radix of arbitrary size. Clearly, a radix-R butterfly would need the input of R-1 non-trivial twiddle factors, rather than the three discussed here. For the SIMD-based solution, the arithmetic and memory components of the space-complexity for the case of a length-N transform may be approximated by

and

words, whilst for the pipelined solution, the arithmetic and memory components of the space-complexity may be approximated by

and

words. As a result, the arithmetic component of the space-complexity for the pipelined solution is approximately (R-2)/(R-1) that of the SIMD-based solution, whilst its memory component is just 1/(R-1) that of the SIMD-based solution, making the two solutions comparable, for sufficiently large R, in terms of their arithmetic component, but with the pipelined solution being clearly increasingly more memory-efficient, with increasing R, and thus making it particularly attractive for those big-data memory-intensive applications involving the use of long to ultra-long FFTs.

A comparison of the space-complexities for the two solutions, for various FFT radices and transform lengths, is provided in

Table 2, whereby the relative attractions of the two schemes for different scenarios are evident. The larger FFT radices are included purely for the purposes of illustration and, although the amount of resources clearly increases with increasing radix, it is also the case that greater parallelism is achievable with the larger-sized butterfly so that the computational throughput may also be commensurately increased in terms of outputs per clock cycle. As one would expect, only the memory component of the space-complexity for the twiddle factor computation varies as the transform length is increased.

6. Summary and Conclusions

The paper has described two schemes, together with architectures, for the resource-efficient parallel computation of twiddle factors for the fixed-radix version of the FFT algorithm. Assuming a silicon-based hardware implementation with a suitably chosen parallel computing device, the two schemes have shown how the arithmetic component of the resource requirement, as expressed in terms of the numbers of hardware multipliers and adders, may be traded off against the memory component, as expressed in terms of the amount of RAM required for constructing the LUTs needed for their storage. Both schemes showed themselves able to achieve the throughputs needed for the associated butterfly and its FFT to achieve and maintain real-time operation.

The first scheme considered was based upon the adoption of the SIMD technique, as applied in the spatial domain, whereby the PEs operated independently upon their own individual LUTs and were thus able to be executed simultaneously, whilst the second scheme was based upon the adoption of the pipelining technique, as applied in the temporal domain, whereby the operation of all but the first LUT-based PE was based upon second-order recursion using previously computed PE outputs. Both schemes were assessed using the radix-4 version of the FFT algorithm, together with the two-level version of the LUT, as these two algorithmic choices facilitated ease of illustration and offered the potential for flexible computationally-efficient FFT designs – the attraction of the radix-4 butterfly being its simple design and low arithmetic complexity, with the attraction of the two-level LUT being a memory requirement of just , as opposed to the of the more commonly used single-level LUT, making it ideally suited to the task of minimizing the twiddle factor storage.

The study concluded with a brief comparative analysis of the resource requirements which showed that for the pipelined solution, the arithmetic component of the space-complexity was approximately two-thirds that of the SIMD-based solution, whilst its memory component was just one-third that of the SIMD-based solution, making the pipelined solution the more resource-efficient – and thus able to achieve a higher computational density – of the two studied solutions and particularly attractive, due to the low memory component, for those big-data memory-intensive applications involving the use of long to ultra-long FFTs.