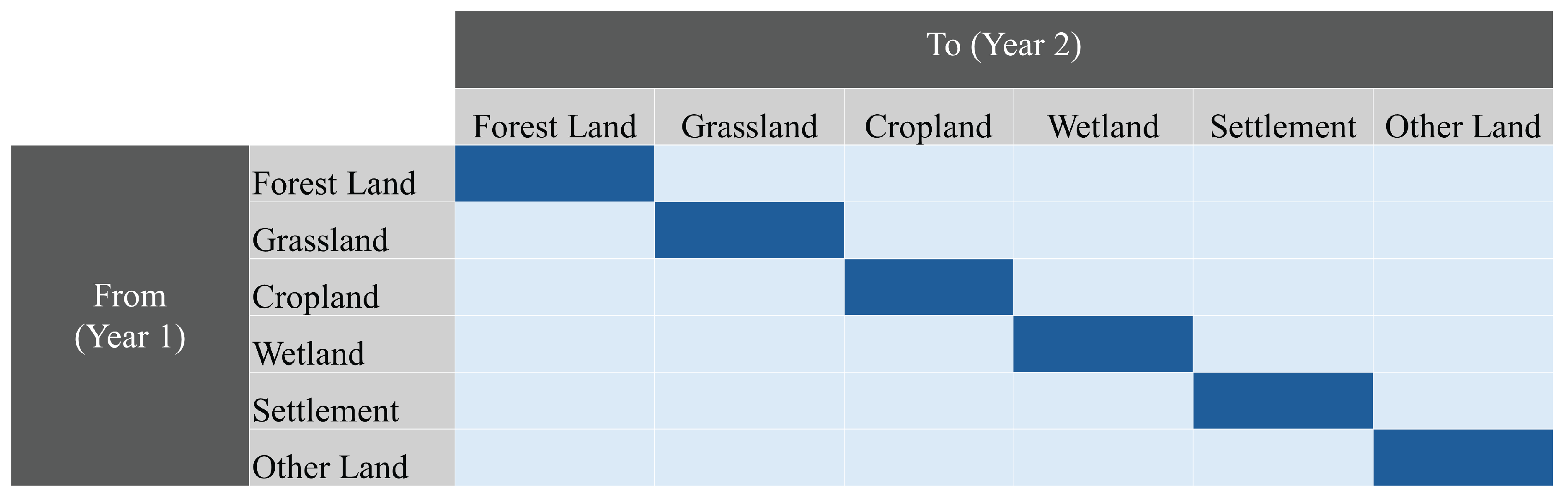

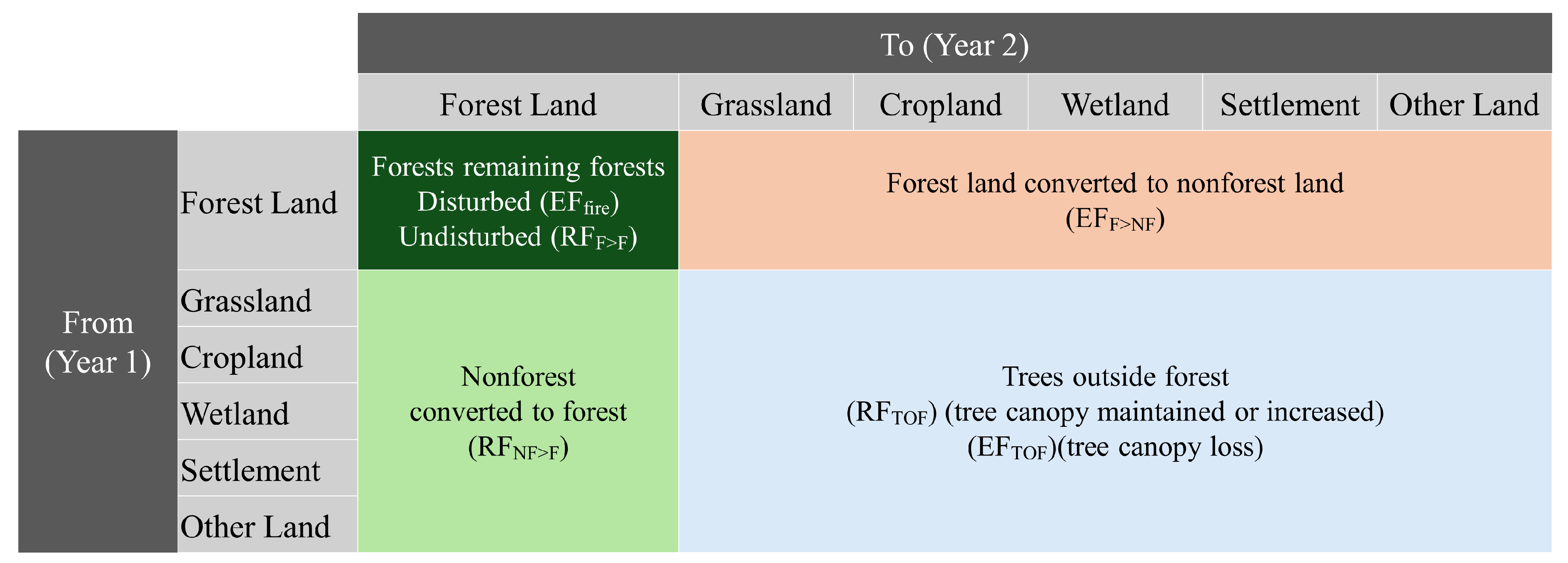

Appendix B.1. Emission and Removal Factors Framework

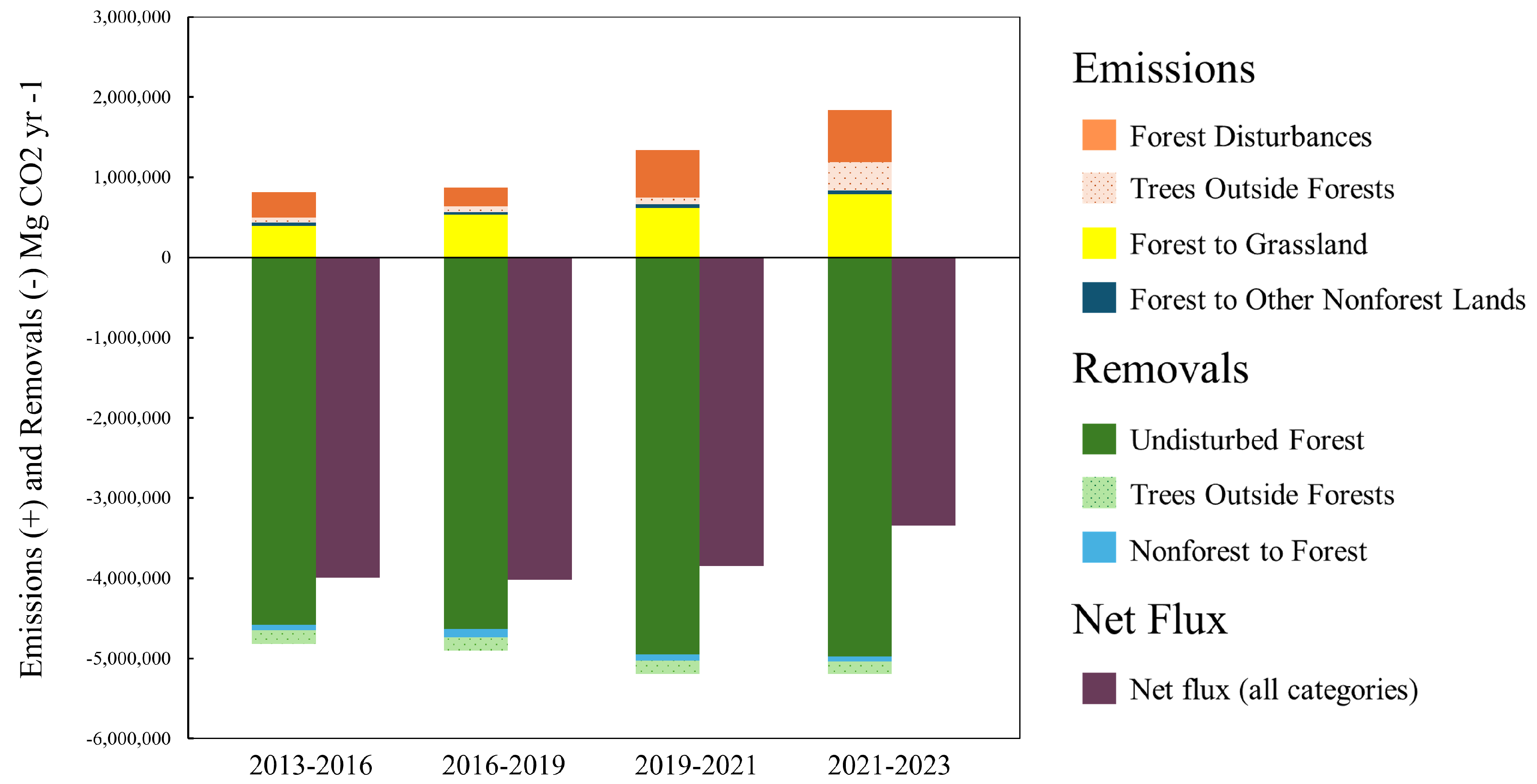

Emission and removal factors used in LEARN were developed for 11 geographic regions of the conterminous United States, selected to broadly represent distinct climatic zones and historical land management practices. These regional factors are further stratified by forest stand origin (natural or plantation), forest type group, and age class (0–20, 20–100, and 100+ years). The regional approach aligns closely with the methodologies described by the IPCC, specifically aligning with Tier 2 and Tier 3 methods. Tier 2 methodologies involve the use of national forest inventory data to derive regionally representative emission and removal factors, while Tier 3 integrates repeated direct inventory measurements with detailed remote sensing data, providing a high degree of spatial and temporal specificity.

The approach described here is consistent with IPCC guidelines and also aligns with USDA guidelines for entity-scale quantification of greenhouse gas emissions and removals in forestry [

9], as well as methodologies used in annual greenhouse gas inventories reported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [

26]. Specifically, LEARN integrates emission and removal factors derived from detailed analyses of repeated FIA measurements managed by the USDA FS. Biomass carbon stocks and stock changes in live trees are calculated based on individual tree measurements of diameter and height from FIA plots, which are converted to biomass using standardized equations. Non-biomass carbon pools are estimated using empirical models derived from FIA measurements, as detailed in [

27] and [

31]. Detailed methodological descriptions and underlying assumptions used to derive these emission and removal factors, including data selection, statistical methods, and regional adjustments, are extensively documented in Glen et al. 2024 [

13].

Appendix B.2. Data Sources

Emission and removal factors were derived primarily using data from the FIA database maintained by the USDA FS. This database provides extensive plot-level data collected systematically across the conterminous United States. FIA data include direct measurements of tree diameter, height, and species, which are converted into biomass and carbon stock estimates using standardized biomass equations. Non-biomass carbon pools, including dead wood, forest floor, and soil organic carbon, are modeled based on empirical relationships established from detailed measurements on a subset of FIA inventory plots, following methodologies described in [

27] and [

31].

Forest type classifications and forest stand age used in LEARN are derived from BIGMAP, a modeling effort led by the FIA program. BIGMAP integrates data from over 213,000 FIA inventory plots measured from 2014–2018, approximately 4,900 Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager scenes collected during the same period, and auxiliary climatic and topographic raster datasets. Landsat scenes were processed specifically to extract vegetation phenology data, which along with climatic and topographic information, informed an ecological ordination model assigning FIA-derived attributes (forest type group, stand age, stocking, and Lorey’s height) to individual pixels [

5].

Forest type group classifications from BIGMAP align directly with FIA, providing ecologically meaningful classifications to enhance accuracy for estimating emissions and removals. Forest stand age data from BIGMAP provide detailed spatial distributions reflecting variability related to historical disturbances and reforestation practices. LEARN employs three distinct stand-age classes (0–20, 20–100, and 100+ years) to represent different growth dynamics and carbon sequestration potential post-disturbance. Where forest pixels identified by NLCD lacked corresponding forest type group or stand age within BIGMAP, data were extrapolated from adjacent mapped areas.

Planted and intensively managed forests are delineated separately due to significantly higher growth rates compared to naturally regenerated forests, particularly in the South and Pacific Northwest regions. Plantation areas were identified using the Spatial Database of Planted Trees [

18], which incorporates publicly available spatial layers from the USDA FS filtered by forest type, timberland extent, forest age, ownership, protected status, and typical rotation ages. Seven forest types commonly associated with plantations—Douglas fir, loblolly pine, loblolly pine/hardwood, shortleaf pine, shortleaf pine/oak, slash pine, and slash pine/hardwood—were included in this delineation. These mapped plantation areas specifically support improved accuracy of LEARN emission and removal estimates. Efforts are currently underway to develop a 30-meter resolution stand-origin dataset through the BIGMAP modeling framework, intended for future integration into LEARN.

Appendix B.4. Undisturbed Forests Remaining Forests

Removal factors for undisturbed forests were developed using the FIA database accessed through the EVALIDator query tool provided by the USDA FS. To ensure accuracy, plots with recent recorded disturbances (such as fire, harvesting, or severe insect mortality) or atypical stocking conditions (below 60% or above 120% stocking, depending on region) were systematically excluded. Plots that had stocking greater than 120 percent in the eastern United States were also removed since these “overstocked” stands represent unusual conditions of high-density tree populations that do not represent typical fully stocked growing conditions. In the South and Pacific Northwest, where forests are more intensively managed than other regions and understocked forests quickly become fully stocked, the <60 percent stocking filter was not included. Planted and intensively managed forests were separated from other forests, primarily in the South and Pacific Northwest, because their growth rates are significantly higher than less intensively managed forests.

Removal rates were estimated using two approaches, depending on data availability (East versus West) and varied by carbon pool, with modifications to address insufficient data. In the East, all states had at least one complete remeasurement cycle of 5 to 10 years available in the database, and the most recent complete inventory cycle was selected for analysis. For biomass, database variables included estimates of average annual change in biomass or carbon (above- and belowground) by age class on a per-acre basis, allowing for a remeasurement approach to estimate removal rates. All variables were converted to consistent units of megagrams of carbon per hectare per year (Mg C/ha/yr). Data were retrieved in 10- or 20-year age-class groups by forest type for each region, provided sufficient sample plots were available based on sampling errors reported in the FIA database. Area-weighted averages across 20-year age classes were calculated for the 20–100 and 100+ year age-class categories.

For other carbon pools in the East, data were available as carbon stocks per acre for different age classes, requiring the use of a stock-difference approach. Average annual change was estimated by calculating the difference in estimated stocks at two time points, divided by the number of years, and converted to Mg C/ha/yr. Where data were sparse, subsets of available age classes most representative of the period of interest were used to estimate annual changes.

In the West, similar methods were employed, but due to the lack of remeasurement data, the stock-difference approach was exclusively used for biomass and other carbon pools. Unlike the East, plots with stocking greater than 120 percent were not excluded due to the risk of losing too many plots, which would result in inadequate representation of older stands common in the region.

In cases where FIA data were insufficient for certain uncommon forest types (approximately 10 percent of total forest area), removal factor estimates were derived from analogous forest types in adjacent regions or closely related forest types within the same region. This approach ensures consistency and minimizes gaps in data coverage.

Sampling errors associated with removal factors are relatively low due to the substantial number of sample plots contributing to regional estimates. However, these errors represent region-wide sampling uncertainty and do not include additional errors (or biases) when applying these factors at smaller scales. LEARN employs a map-based weighting procedure to minimize bias by estimating area-weighted averages by forest type and age class specific to the area of interest. Nonetheless, community-specific conditions significantly different from regional averages may lead to larger errors.

Additionally, sampling errors do not account for modeling errors. Biomass and other carbon pools are not directly measured; rather, they are estimated using models relating easily measured attributes, such as tree diameter, or categorical classifications such as forest type. Modeling errors can be substantial, potentially introducing significant bias if models inadequately represent the population of trees in the local inventory domain.

The inclusion of small-scale and low-severity disturbances in calculating removal factors is unlikely to lead to substantial underestimation or overestimation of net emissions because removal factors are harmonized with activity data. Such disturbances typically recover quickly within the inventory period, aligning well with undisturbed forest calculations. However, these small-scale and low-severity disturbances are not explicitly characterized in activity data, and thus their contributions to emissions and removals are not separately identified. The removal factors inherently include compensating biases from these small-scale events.

Resulting removal factors represent net annual carbon increments for each region and forest type group, explicitly incorporating aboveground and belowground live biomass, standing and down dead wood, forest floor, and soil organic carbon (to a depth of one meter). Currently available soil carbon data do not vary by age class and thus do not influence age-related removal estimates, except for the "nonforest converted to forest" category, described in a subsequent section. Generally, young forests (0–20 years) exhibit higher removal rates due to rapid growth, mature forests (20–100 years) demonstrate intermediate rates, and older forests (100+ years) show significantly reduced removal rates resulting from natural mortality and increased decomposition.

Appendix B.6. Trees Outside Forests

Emission and removal factors for trees outside forests were derived primarily from urban forestry data documented by [

20], due to the absence of comprehensive data covering rural or other nonforest landscapes with dispersed trees. (see Figure

Table A2) and (see Figure

Table A3) present illustrative examples of emission and removal factors from representative cities and states in the northeastern United States. Similar methods and criteria were consistently applied to select representative cities and states across all regions. Given this limitation, it was assumed that trees in nonforest areas (including rural agricultural and suburban landscapes) exhibit carbon dynamics more similar to urban trees, rather than forest trees, which typically have significantly higher densities and different carbon dynamics.

Table A2.

Example of emission factors for trees outside forests in select cities in the Northeastern U.S. Standard error calculated at the 67% confidence level based on biomass data from FIA sample plots [

20]. For a 95% confidence level, multiply the standard error by 1.96.

Table A2.

Example of emission factors for trees outside forests in select cities in the Northeastern U.S. Standard error calculated at the 67% confidence level based on biomass data from FIA sample plots [

20]. For a 95% confidence level, multiply the standard error by 1.96.

| City & State |

Emission Factor (Mg C/ha) |

Standard Error (%) |

| Baltimore, MD |

103.0 |

12 |

| Boston, MA |

70.2 |

14 |

| Camden, NJ |

110.4 |

61 |

| Chester, PA |

88.3 |

14 |

| Hartford, CT |

109.9 |

15 |

| Jersey City, NJ |

43.7 |

20 |

| Morristown, NJ |

99.5 |

9 |

| Morgantown, WV |

95.2 |

12 |

| New York, NY |

63.2 |

12 |

| Philadelphia, PA |

86.5 |

17 |

| Scranton, PA |

92.4 |

14 |

| Syracuse, NY |

94.8 |

11 |

| Woodbridge, NJ |

81.9 |

10 |

Removal factors associated with canopy growth or maintenance were provided as state-level averages. These estimates, documented in the U.S. EPA’s national greenhouse gas inventories [

26], were originally derived by Nowak et al. [

20] and represent average annual carbon removals by tree canopy within urbanized areas across each state. Emission factors linked to canopy loss were developed at the city-specific level, reflecting local variations in urban tree composition, density, and management practices.

Table A3.

Removal factors for trees outside forests in select states in the Northeastern U.S. Standard error calculated at the 67% confidence level based on biomass data from FIA sample plots [

20]. For a 95% confidence level, multiply the standard error by 1.96.

Table A3.

Removal factors for trees outside forests in select states in the Northeastern U.S. Standard error calculated at the 67% confidence level based on biomass data from FIA sample plots [

20]. For a 95% confidence level, multiply the standard error by 1.96.

| State |

Removal Factor (Mg C/ha/year) |

Standard Error (%) |

| Connecticut |

-2.62 |

17 |

| Delaware |

-3.66 |

21 |

| Maine |

-2.42 |

18 |

| Maryland |

-3.53 |

19 |

| Massachusetts |

-2.78 |

17 |

| New Hampshire |

-2.38 |

18 |

| New Jersey |

-3.21 |

17 |

| New York |

-2.63 |

17 |

| Pennsylvania |

-2.67 |

17 |

| Rhode Island |

-2.83 |

19 |

| Vermont |

-2.34 |

19 |

| West Virginia |

-2.64 |

18 |

In instances where data for specific geographies are unavailable, users should select representative cities that most closely match the geographic location, climatic conditions, urban tree composition, and overall land management practices of the nonforest area being analyzed. Selecting an appropriate representative city enhances the accuracy of emission estimates by better reflecting local conditions. Where uncertainty exists regarding the best representative city, it is recommended to consult regional forestry experts or review supplementary materials provided with the original datasets to make informed selections.

Due to limited data availability for other types of nonforest land with trees (e.g., cropland, pasture, and nonforest wetlands), the urban-derived factors were applied broadly across these nonforest landscapes, assuming similar biomass densities and growth rates for open-grown trees regardless of their specific land-use context. This generalized approach ensures consistent and comparable estimation of carbon emissions and removals associated with trees outside forests.

Appendix B.7. Forest Converted to Nonforest

Emission factors for forest-to-nonforest conversions were developed by applying standardized carbon loss percentages derived from EPA guidelines to baseline carbon stocks. Baseline carbon stocks were estimated using data from the BIGMAP Biomass and Carbon Pools dataset [

5], which provides spatially explicit, high-resolution (30-meter) estimates of forest carbon stocks. These baseline stocks were categorized by LEARN into living biomass (aboveground, belowground, and understory), dead organic matter (standing dead trees, coarse woody debris, and litter), and soil organic carbon pools.

Carbon stock estimates for each identified forest-to-nonforest land-use transition type were calculated and then multiplied by associated default carbon loss percentages. These percentages vary depending on the subsequent land-use type, such as conversion to cropland, grassland, settlements, or other developed land uses, with the highest carbon loss percentages typically associated with conversion to intensively managed or developed land uses [

26].

Table A4.

National average percent of carbon (C) stock lost upon conversion of forest to different non-forest land uses, by carbon pool [

26].

Table A4.

National average percent of carbon (C) stock lost upon conversion of forest to different non-forest land uses, by carbon pool [

26].

| |

Forest Converted to … |

| Carbon Pool |

Cropland |

Grassland |

Wetland |

Settlement |

Other Land |

| Biomass C |

100 |

50 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Dead organic matter C |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Organic soil C |

23 |

0 |

0 |

30 |

100 |

Due to the inherent variability and uncertainties regarding exact proportions of carbon loss from different carbon pools, these default percentages provide an essential standardized basis for estimating emissions. Users lacking specific local data are recommended to utilize these EPA-derived default percentages to ensure consistency and comparability in emission estimates across assessments. However, users with detailed local information on land-use conversion impacts are encouraged to apply site-specific carbon loss percentages to enhance accuracy. This approach allows for robust, spatially explicit, and consistent estimation of emissions resulting from the conversion of forest lands to nonforest categories, ensuring alignment with national greenhouse gas inventory practices.

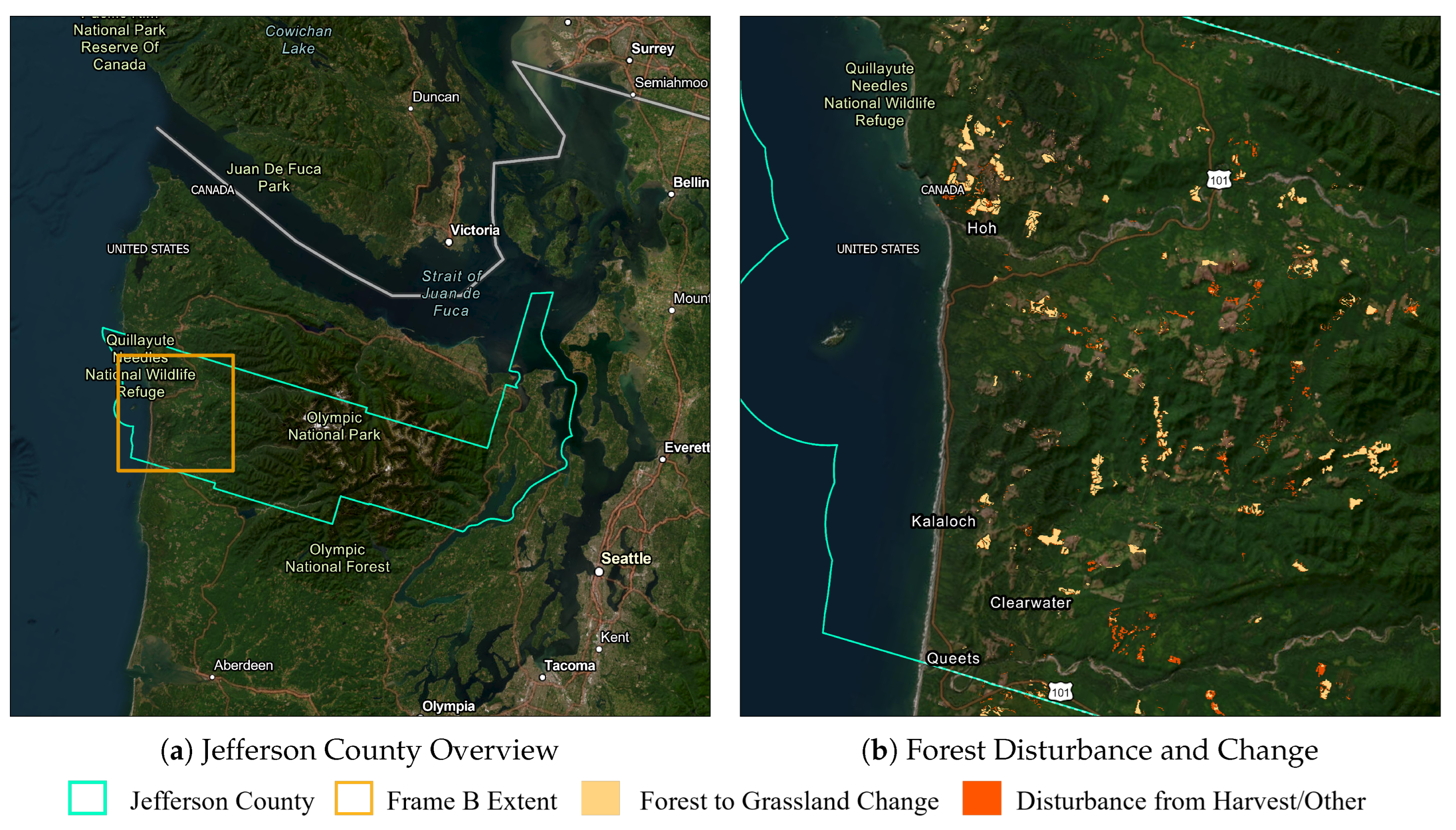

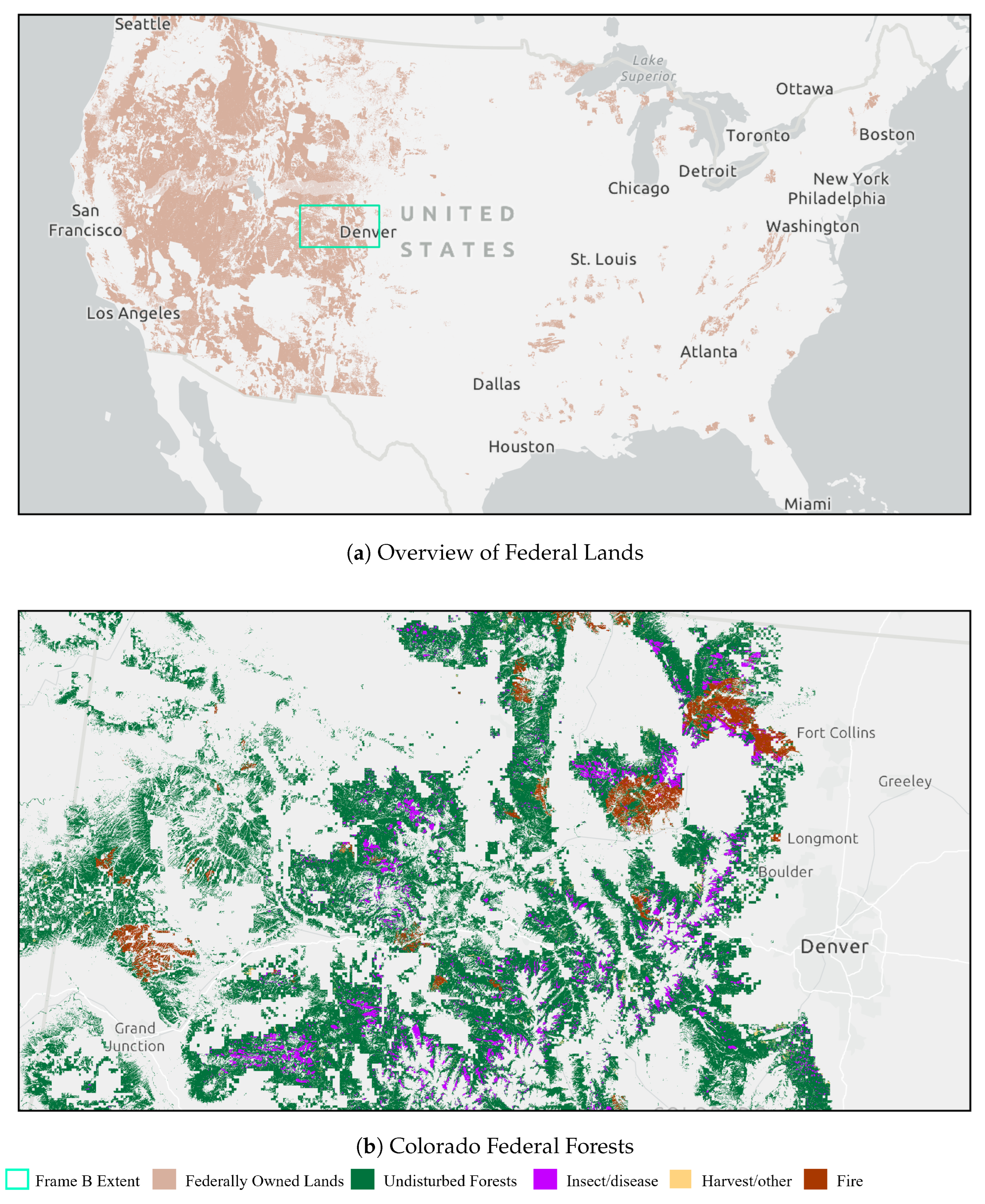

Appendix B.8. Forest Disturbances

Emission factors for forest disturbances—including fire, insect and disease mortality, and timber harvest or other disturbances—were derived primarily from comprehensive regional studies by [

25] and [

21]. These studies conducted detailed analyses of pre- and post-disturbance carbon stocks using data from FIA.

Disturbance emission factors specifically represent carbon losses resulting from high-severity disturbances, defined as events affecting 50% or more of the forest canopy. The emission factors vary by disturbance type, severity class, forest type group, region, and initial carbon stock levels. They reflect immediate carbon losses associated with biomass combustion in fires, tree mortality, subsequent decomposition of dead material, and reductions in soil organic carbon.

Due to the complexity of disturbance dynamics, LEARN employs a simplified yet rigorous approach. Emission factors for disturbances were initially calculated from FIA data in national forests and subsequently applied across broader public and private forest lands within corresponding regions, assuming similarities in forest composition and disturbance impacts. Although this approach introduces some uncertainty, it ensures comprehensive and regionally consistent estimates.