2.1. Chemical Characterization of Extract and Fractions from Isostichopus sp. aff badionotus.

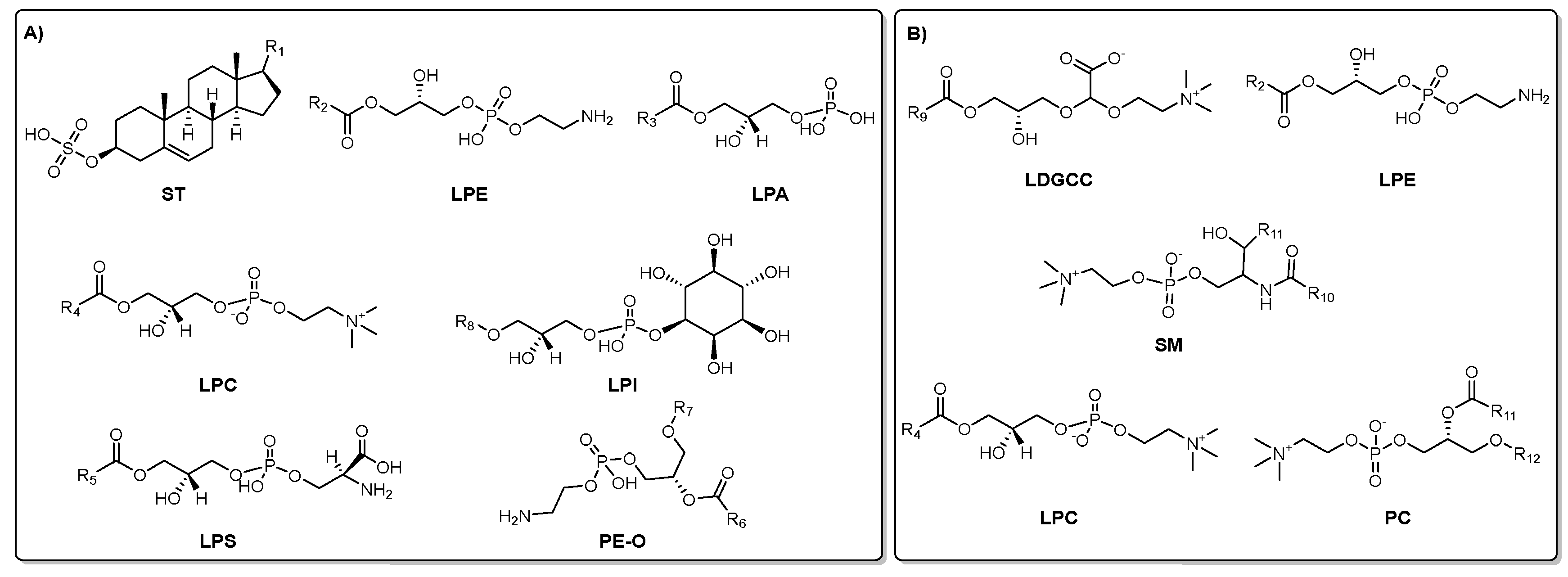

The UHPLC-QTOF-MS-based chemical characterization aimed to reveal the profile of specialized metabolites present in each extract/fractions and assess the effectiveness of the fractionation strategy. This approach was conducted in both positive and negative ionization modes to ensure comprehensive detection. High-resolution monoisotopic masses, tandem MS/MS fragmentation patterns, and chromatographic retention times were systematically compared against spectral databases including MS-DIAL, MoNA (MassBank of North America), and LipidBlast for accurate compound annotation. This analysis exposed a diverse array of lipid-derived specialized metabolites. In the negative ionization mode, compounds were primarily associated with classes such as lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), lysophosphatidic acids (LPA), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylserines (LPS), phosphoethanolamines (PE-O), glycerophosphoinositols (LPI), and sulfated sterols (ST). Conversely, positive ionization mode predominantly identified lipids including lysodiacylglycerylcarboxyhydroxymethylcholines (LDGCC), sphingomyelins (SM), LPEs, phosphatidylcholines (PC), and LPCs.

Figure 2 depicts representative molecular structures of the major specialized metabolites detected under each ionization condition, with panel A corresponding to those annotated in negative mode and panel B to those in positive mode.

Figure 1.

Annotated compound classes in I. sp. aff badionotus extract and fractions by UHPLC-MS/MS-based analysis. A) Metabolites detected and annotated in negative mode. B) Metabolites detected and annotated in positive mode. Lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), lysophosphatidic acids (LPA), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylserines (LPS), phosphoethanolamines (PE-O), glycerophosphoinositols (LPI), sulfated sterols (ST), lysodiacylglycerylcarboxyhydroxymethylcholines (LDGCC), sphingomyelins (SM), phosphatidylcholines (PC).

Figure 1.

Annotated compound classes in I. sp. aff badionotus extract and fractions by UHPLC-MS/MS-based analysis. A) Metabolites detected and annotated in negative mode. B) Metabolites detected and annotated in positive mode. Lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), lysophosphatidic acids (LPA), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylserines (LPS), phosphoethanolamines (PE-O), glycerophosphoinositols (LPI), sulfated sterols (ST), lysodiacylglycerylcarboxyhydroxymethylcholines (LDGCC), sphingomyelins (SM), phosphatidylcholines (PC).

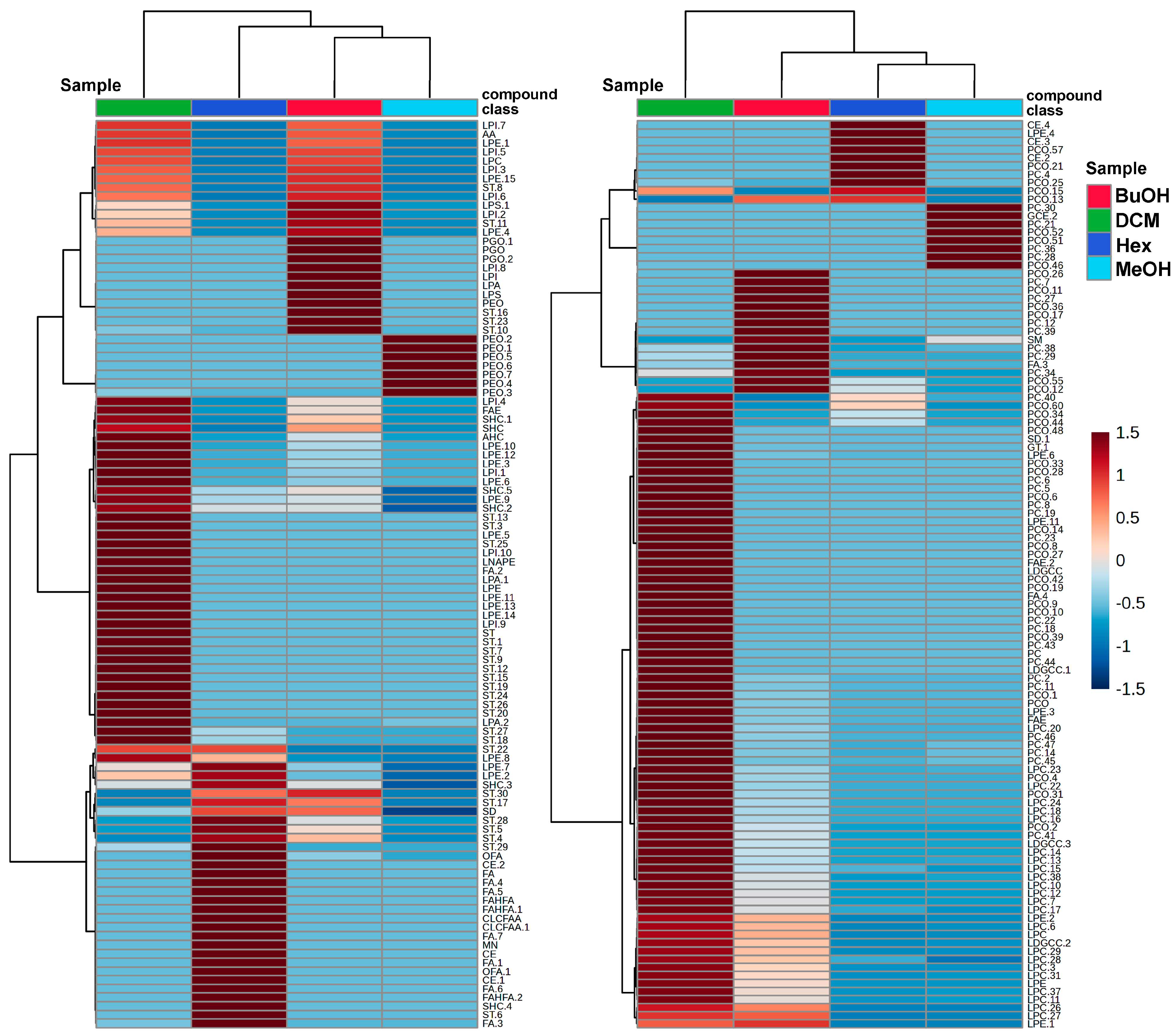

The distribution and relative abundance of the annotated metabolites across the different extract and its derived fractions are intuitively visualized in the heat map (

Figure 2), which presents two subsets of detected compounds obtained under negative and positive ionization modes (

Figure 2A and 2B, respectively). Metabolite intensities were normalized and visualized using a color gradient, with red tones indicating higher abundance and blue tones representing lower abundance. Thus, hierarchical clustering of both subsets and extract/fractions revealed distinct chemical profiles among the fractions, emphasizing the efficiency of the liquid–liquid partitioning in segregating metabolites based on solvent removal. The DCM fraction showed the highest diversity and intensity of detected metabolites (especially in positive mode), suggesting enrichment of moderately polar metabolites (mainly ST, LPE, LPC, LDGCC, and PC) in both subsets. The BuOH fraction also retained several polar and amphiphilic compounds (e.g., LPI, LPA), some overlapping with those in the DCM fraction (ST, LPE, PC).

In contrast, the Hex fraction exhibited a more restricted profile, enriched in a narrower set of non-polar metabolites (fatty acids, terpenoids, and miscellaneous). The parent MeOH extract exhibited an unfractionated chemical profile, characterized by intermediate levels of many annotated metabolites, and served as a baseline for comparative analysis. This profile likely reflects the presence of residual compounds (e.g., PE, PC) that were not entirely removed during the partitioning process, consistent with its role as the original matrix encompassing a broader diversity and potentially higher abundance of metabolites. Consequently, the clustering patterns and differential distribution confirm that solvent-guided fractionation effectively separated metabolites according to their physicochemical properties. Notably, the BuOH and DCM fractions retained a higher abundance of structurally diverse metabolites, supporting their potential role in the observed biological activities and underscoring their relevance for pharmacological investigation.

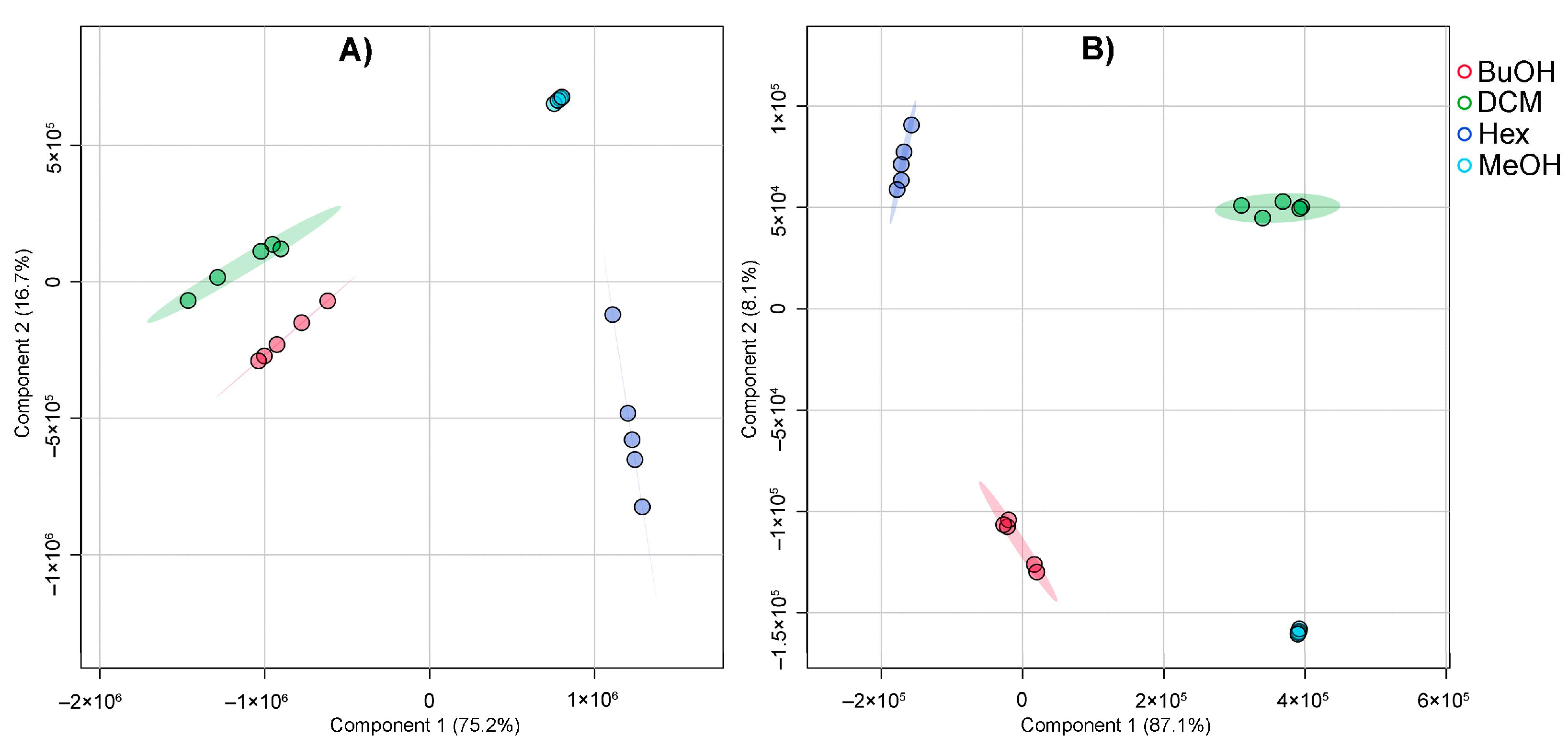

Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) was employed to assess the metabolic differences among the MeOH extract and its derived solvent fractions. As shown in

Figure 3, the PLS-DA score plots clearly differentiate the samples based on their chemical profiles under both negative (

Figure 3A) and positive (

Figure 3B) ionization modes. In the negative ionization mode (

Figure 3A), the first two components explained 75.2% and 16.7% of the total variance, respectively. The score plot reveals a distinct clustering of all four extract/fraction types, indicating that each extract/fraction harbors a unique metabolite composition. The BuOH and DCM fractions form separate, tight clusters, suggesting well-defined chemical profiles enriched in polar and moderately polar compounds, respectively. The Hex fraction, dominated by non-polar metabolites, is clearly separated along Component 1. Meanwhile, the MeOH extract occupies a unique position between the fractions, reflecting its broader chemical diversity as the parent extract.

In the positive ionization mode (

Figure 3B), the first two components account for 87.1% and 8.1% of the variance, indicating strong discriminative power of the model. As in the negative mode, the extract/fractions form well-separated clusters with minimal overlap. Again, the BuOH and DCM fractions show strong clustering, highlighting their compositional consistency. The Hex fraction appears more distinct in this mode, and the MeOH extract is again positioned between the extremes, further supporting its role as a chemically rich and heterogeneous matrix. The PLS-DA-derived outcome demonstrated that solvent partitioning effectively segregated metabolite classes based on their polarity and ionization properties. The clear separation among extract/fraction types reinforces the utility of this approach in enriching and distinguishing specialized metabolite subsets for further bioactivity evaluation.

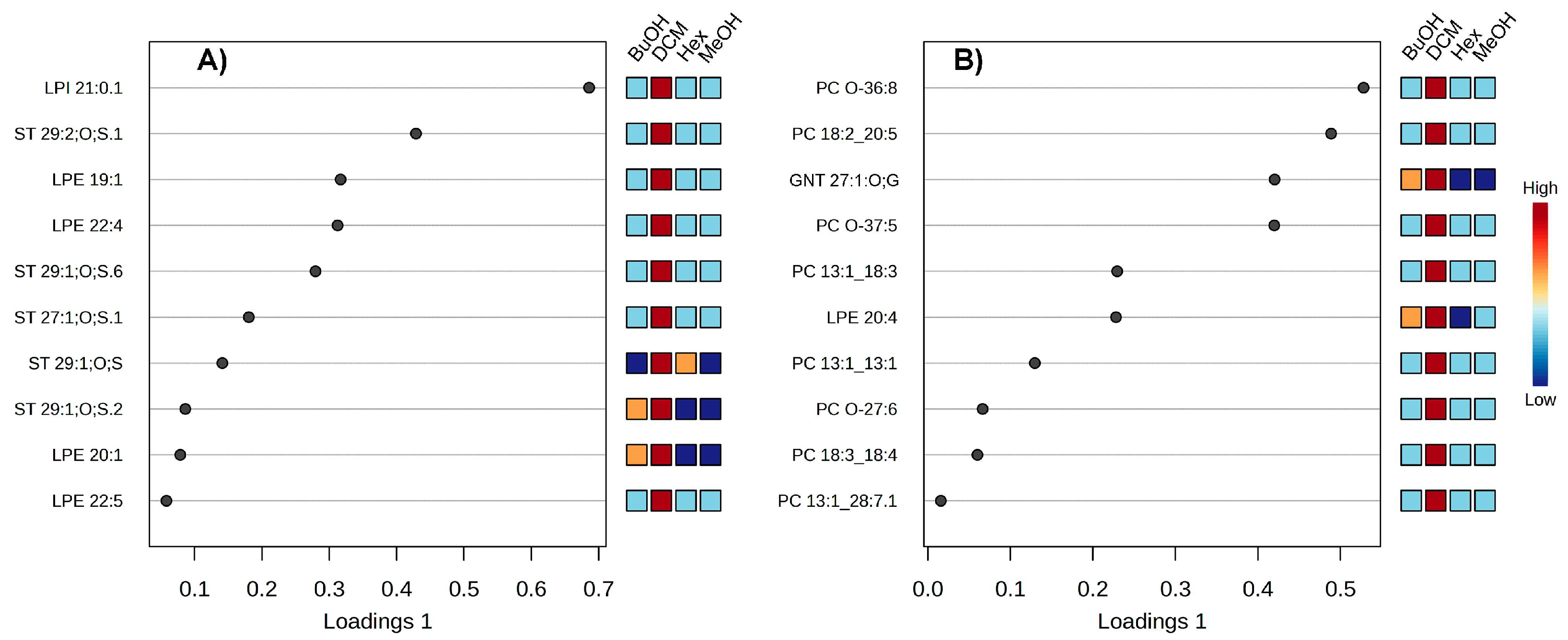

To identify the metabolites driving the separation observed in the PLS-DA score plots, the corresponding loadings plots (

Figure 4) were analyzed for both negative (Panel A) and positive (Panel B) ionization datasets. The compounds displayed represent the top contributors (highest loadings on component 1) to the discriminative power of the model. In negative ion mode (

Figure 4A), lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI 21:0:1) and several lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPEs), such as LPE 22:4 and LPE 22:5, were among the most influential compounds. Sulfated sterols (e.g., ST 29:1;O;S and ST 27:1;O;S) also exhibited strong discriminative contributions. The associated heatmap reveals distinct patterns of metabolite distribution across extract/fractions, e.g., sulfated sterols were particularly enriched in the DCM and Hex fractions, whereas LPEs showed higher abundance in BuOH and MeOH, reflecting the polarity-dependent partitioning of these lipids.

In positive ion mode (

Figure 4B), discriminant features included several phosphatidylcholines (PCs), such as PC_O-36:8, PC_18:3_18:4, and PC 13:1_28:7:1, along with LPE 20:4 and a glycosylated alkyl-substituted nor-terpenoid (GNT 21:1;O;G). These metabolites showed strong associations with the BuOH and DCM fractions, with phosphatidylcholines more abundant in DCM and BuOH fractions, consistent with their intermediate polarity. Notably, the MeOH extract exhibited moderate levels for most metabolites, underscoring its broad and unspecific metabolite composition as the parent matrix. Collectively, these findings highlight the selective enrichment of lipid subclasses in each solvent fraction. Sulfated sterols and PCs play a pivotal role in differentiating the extract/fractions, supporting the efficiency of the partitioning strategy to segregate bioactive lipid species and providing a chemical rationale for targeted downstream bioactivity assays.

On the other hand, the distribution of STs across the solvent fractions revealed distinct patterns according to ionization mode and fraction polarity. Under negative ionization, ST compounds were particularly enriched in the butanol (BuOH) and dichloromethane (DCM) fractions, accounting for 36.52% and 17.46% of the total metabolite content, respectively. A lower proportion was detected in the Hex fraction (2.16%), while STs were observed at very low abundance in the methanol (MeOH) fraction. In contrast, the positive ionization mode revealed that PCs were the predominant lipid class detected, with their relative abundance varying across extract/fractions: 10.64% in DCM, 5.88% in BuOH, 4.82% in Hex, and 3.28% in MeOH. These results demonstrate that DCM and BuOH fractions are richer in key specialized metabolites, while the MeOH extract contains lower proportions of both ST and PC families.

2.2. Molecular Networks Based on the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS)

To explore and connect the UHPLC-MS-based chemical diversity of specialized metabolites present in

I. sp. aff. Badionotus across fractions, we further analyzed the chemical profiles through the global natural product social (GNPS) molecular networking computational web platform. The generated molecular networks (

Figure 5) visually represent the chemical space occupied by specialized metabolites in the four solvent extract/fractions. In both negative (panel A) and positive (panel B) ionization modes, clusters of structurally related metabolites were evident, indicating chemical diversity and specificity across extract/fraction types. Based on mass and fragmentation patterns, molecular networks were then examined. The color distribution within clusters indicated that certain metabolite families are exclusive to specific extract/fractions, while others are shared among two or more solvents, revealing the complementary nature of the fractionation. DCM and BuOH share many chemical features, likely due to overlapping polarity ranges, which might explain the shared presence of key sterols and lipids. On the other hand, Hex and MeOH show fewer shared nodes, reflecting their extraction of chemically distinct metabolite sets—non-polar lipids in Hex and hydrophilic or polar compounds in MeOH. The network analysis confirms that DCM and BuOH fractions harbor the highest chemical diversity, particularly for bioactive specialized metabolites, while the MeOH and Hex fractions show lower complexity or narrower chemical space coverage. These insights reinforce the importance of using a polarity-gradient extraction strategy to capture the broadest spectrum of marine-derived metabolites.

The network obtained from the dataset in negative mode (

Figure 5A), which is particularly suitable for detecting acidic and sulfated compounds such as sulfated sterols, reveals thirteen densely interconnected clusters predominantly colored in light blue and dark green—indicative of the DCM and BuOH fractions, respectively. These results support the earlier analysis showing a high abundance of sulfated sterols in these two fractions. Hexane fraction (light green) contributes only a few nodes, which agrees with its lower extraction efficiency for polar or ionizable compounds. Metabolites in the methanolic extract (dark blue nodes) are sparsely distributed, highlighting a comparatively lower chemical diversity or ionization efficiency in this mode.

These analyses revealed that cluster N1 involved PE-type compounds with different side chains and substitution patterns, which were mainly identified in the BuOH and DCM fractions, with a higher percentage in the DCM, reaffirming its richness in this lipid-like composition (

Figure 6A). This well-defined cluster shows a clear pattern in mass (e.g., m/z 478.3, 490.2, 506.8), consistent with a PE-like lipid core modified by alkyl chain variations.

Similarly, STs were grouped within the same cluster (N2) in their [M–H]⁻ form (

Figure 6B), suggesting structural similarity. This dense network is composed primarily of nodes with light blue and dark green borders, indicating the dominance of metabolites in the DCM and BuOH fractions. The high connectivity suggests a family of structurally related compounds, potentially sterol-like lipids or sulfated triterpenoids, abundant in sea cucumbers and known for their bioactivity. The consistent

m/z spacing and node proximity suggest sequential modifications such as hydroxylation or sulfation. In this regard, an abundant ST exhibited an MS² fragment ion with

m/z 96.960 ([M-H]

– = 465.3061), matching the structure of cholesterol-3-sulfate (

1) in the GNPS database, with a cosine score of 0.99. This sulfated sterol

1 has been previously identified in other sea cucumber species and is known as the most abundant sulfated sterol in

Eupentacta fraudatrix, along with other cholestane derivatives and, to a lesser extent, sulfated stigmastanes [

15].

Similarly, metabolite analysis of

Psolus fabricii revealed the presence of the same sterols, although at significantly lower concentrations [

16]. In the case of

Cucumaria frondosa, it was reported that 51% of the pure fraction of sulfated sterols corresponds to cholesterol sulfate. This evidence supports the identification of compound

1 as cholesterol sulfate. In comparison, the precursor ions of other ST-like compounds showed mass differences of 12 Da (+CH₂/–H₂) ([M–H]⁻ = 477.3062) relative to compound

1, while others differed by 14 Da (+CH₂) ([M–H]⁻ = 479.3205) and 16 Da (+CH₂/+H₂) ([M–H]⁻ = 481.3525), consistent with campesterol-type sterols. Both cholestane (compound

1) and campesterol analogs also exhibited hydroxylated variants (+16 Da, +OH). Additional STs displayed a 29 Da increase (+CH₃CH₂) ([M–H]⁻ = 491.3203) relative to compound

1, indicative of stigmastane-type sterols. These sulfated sterols have been previously reported in other sea cucumber species.

The remaining identified clusters in the negative ion mode dataset (N3–N10) were associated with various lipid classes and other compound types. Cluster N3 (m/z 512–854, [M–H]⁻) primarily comprised ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamines (PE-O) and lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), while cluster N4 (m/z 830–928, [M–H]⁻) contained ether-linked phosphatidylglycerols (PG-O). Clusters N5 and N6 (m/z > 564, [M–H]⁻) were attributed to lysophosphatidylinositols (LPI) and lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), respectively. Cluster N7 (m/z < 327, [M–H]⁻) included fatty acids (FA), and cluster N8 (m/z < 339, [M–H]⁻) was dominated by sulfated long-chain hydrocarbons. Cluster N9 (m/z < 532, [M–H]⁻) was assigned to lysoneuroaminophosphatidylethanolamines (LNAPE). Finally, cluster N10 (m/z > 1082) comprised high-molecular-weight, yet unidentified, compounds that may represent complex or conjugated lipids.

A different network topology was observed in positive mode (

Figure 5B), where neutral and basic compounds such as phosphatidylcholines ionize more efficiently. The formed clusters (P1-P10) were more evenly distributed among the extract/fractions, although DCM (light blue) and BuOH (dark green) still dominate, aligning with their richer and more diverse chemical profiles. Notably, more dark blue nodes (MeOH) appeared in this mode compared to the negative mode, suggesting that the methanolic extract contained metabolites more prone to ionization in positive polarity—likely including polar lipids, peptides, or even glycosides.

Detailed analysis of the molecular network obtained in positive ion mode confirmed a high abundance of [M+H]⁺ adducts related to phosphatidylcholines (PC), primarily in the DCM and BuOH fractions.

Figure 7 displays four relevant clusters (P3, P5, P11, and P12), in which the identified compounds mainly belong to the PC family, with a smaller proportion corresponding to lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) and phosphatidylinositols (PI).

The clusters P3 and P5 were dominated by light blue (DCM) and light green (Hex) node borders. It featured ions in the

m/z 490–726 range (e.g., 538.4, 544.3, 550.3, 714.55, 716.57, 726.57), which align with mid-polar lipophilic compounds, possibly free fatty acids, oxidized sterols, or monoglycerides. The connectivity suggested a shared core structure modified by alkyl chain variations or oxidations. The Hex preference reflected their moderate polarity, while DCM’s enrichment hints at a mix of amphipathic or lightly functionalized analogs. In addition, the compact and well-structured cluster P11 also included metabolites with strong BuOH and MeOH representation involving phosphocholine-like species. The similarity between nodes and their consistent MS/MS fragmentation supported a common backbone structure with acyl variation. Their solubility in polar solvents again supported their amphipathic nature and roles in membrane dynamics or bioactive signaling. Finally, this sparse mini-cluster contained larger molecules (e.g., m/z 763.6, 803.6) with mixed extract/fraction prevalence but notable BuOH and MeOH dominance. Their high mass range and limited network connectivity suggested the presence of complex glycosylated compounds, such as the annotated steroidal metabolite glycosylated 3,12-dihydroxycholan-24-oic acid (m/z 803.5612, [M–H]⁻) (

Figure 7), which aligns with the well-documented chemical defense mechanisms of sea cucumbers.

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

In this study, the antibacterial activity of the MeOH extract and its fractions DCM, Hex, BuOH from

I. sp.

aff. badionotus was evaluated at an initial concentration of 1,000 µg/mL against eight clinically relevant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Growth curve analysis revealed that all extract/fractions effectively inhibited bacterial growth by delaying the growth rate of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains, with the DCM fraction exhibiting the most pronounced effect (

Figure 8).

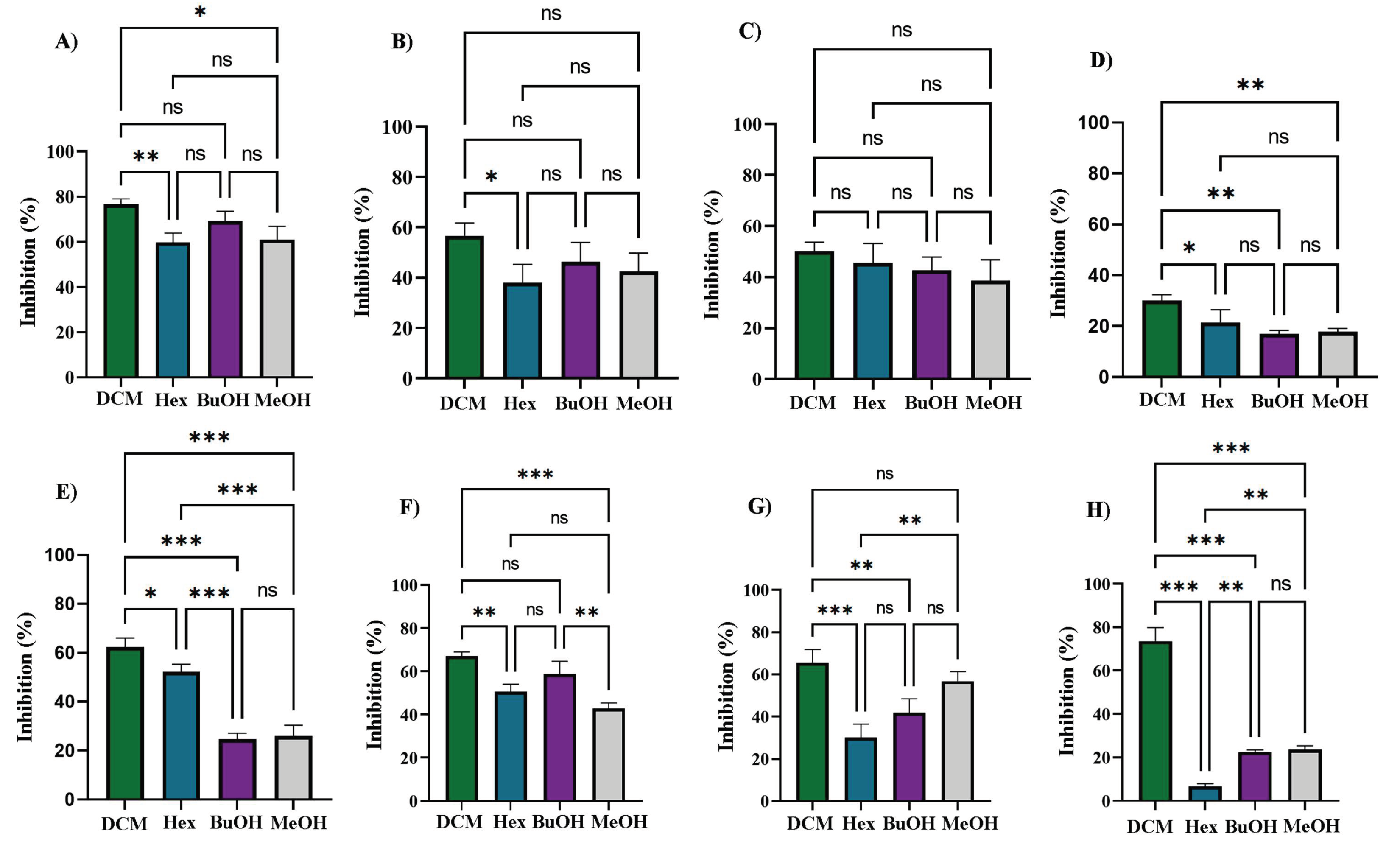

The DCM fraction exhibited significant antibacterial activity, particularly against

E. coli (

Figure 9A), with an inhibition rate of 76.5 ± 2.51%, and against several Gram-positive bacteria:

S. aureus (62.5 ± 3.56%,

Figure 9E),

B. cereus (67.0 ± 2.02%,

Figure 9F),

S. epidermidis (65.5 ± 6.39%,

Figure 9G), and

S. warneri (73.6 ± 6.23%,

Figure 9H). These values were statistically higher than those obtained with the other extract/fractions (

p < 0.05). The Hex and BuOH fractions showed moderate activity, with the highest inhibition also observed against

E. coli, at 59.8 ± 4.06% and 69.2 ± 4.28%, respectively (

Figure 9A). For

K. pneumoniae, the inhibition values were 38.1 ± 7.27% (Hex) and 46.3 ± 3.00% (BuOH) (

Figure 9B); for

S. flexneri, 45.6 ± 7.64% (Hex) and 42.7 ± 5.18% (BuOH) (

Figure 9C); for

S. aureus, 52.2 ± 3.13% (Hex) and 24.6 ± 2.54% (BuOH) (

Figure 9E); and for

B. cereus, 50.5 ± 3.48% (Hex) and 58.9 ± 5.78% (BuOH). In contrast, the MeOH extract displayed only mild antibacterial activity.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the most active extract/fractions was determined to fall within the 1–1,000 µg/mL range. MIC values were calculated using nonlinear regression, fitting the experimental data to the modified Gompertz equation with GraphPad Prism 9.3 [

17]. The calculated MICs aligned with the observed inhibition percentages (

Table 1), confirming the superior activity of the DCM fraction. This outcome suggests that the synergistic effects of its constituent compounds offer promising potential for treating infections, especially those caused by Gram-positive bacteria.

The observed differences in antibacterial activity may be attributed to structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial membranes. Gram-positive bacteria possess a simpler cell wall composed primarily of a thick peptidoglycan layer, which facilitates the permeation of bioactive compounds [

18]. This increased permeability enhances compound access to critical cellular targets, leading to disruption of essential bacterial processes and, ultimately, cell death [

19]. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a more complex cell envelope, consisting of both outer and inner membranes and an intervening layer rich in lipopolysaccharides (LPS). This multilayered structure provides a robust barrier, contributing to resistance against antibiotics, disinfectants, and other lytic agents in the environment [

20].

Structurally, the steroidal compounds identified in the most active DCM and BuOH fractions possess both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, imparting amphipathic properties. This structural polarity is associated with antimicrobial activity, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria, through mechanisms that include destabilization of membrane integrity and increased permeability. These disruptions lead to membrane rupture and leakage of intracellular contents, ultimately resulting in bacterial death [

21,

22]. Additionally, these metabolites may interfere with membrane potential and the proton motive force at the mitochondrial level, further compromising bacterial viability [

23]. These factors may explain the differential antibacterial effects observed between the DCM fraction and the other extract/fractions tested.

The antibacterial activity demonstrated by the test materials from the sea cucumber

I. sp.

aff. badionotus makes a valuable contribution to the field of natural product research. This work supports ongoing efforts to discover potent specialized metabolites from marine sources with activity against clinically relevant pathogens. In recent years, many studies have focused on exploring natural resources due to their diverse array of molecules with antibacterial potential [

24,

25]. Such research has emphasized mechanisms of action targeting bacterial membrane proteins, efflux pumps, biofilm formation, and quorum sensing—all of which play crucial roles in developing antimicrobial resistance [

26]. Natural products may act independently or serve as complementary agents to enhance the efficacy of conventional antibiotic therapies.