Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- In vitro enamel erosion caused by fruit juices, smoothies, vitamin waters, kombuchas, carbonated waters, and sports/energy drinks.

- Clinical or in situ studies correlating these beverages with enamel loss or erosive wear in vivo.

- The typical pH and titratable acidity of these drinks and their relevance to erosive potential.

- Behavioral factors (frequency, consumption method, exercise, etc.) that modify erosion risk.

- Preventive or mitigating strategies, including product modifications (like calcium fortification) and patient behavioral guidance.

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol

Search Strategy

- Population: Human participants of any age OR extracted teeth/enamel samples (for in vitro) exposed to one or more of the beverages of interest.

- Exposure: At least one beverage commonly marketed as healthy, specifically: fruit juices (100% juices or juice blends), smoothies (blended fruit/vegetable drinks, often with yogurt), vitamin waters or similar flavored waters, kombucha or fermented teas, carbonated waters (seltzer, club soda, flavored sparkling water), sports drinks (electrolyte drinks for hydration), or energy drinks (caffeinated stimulant drinks). Studies on traditional soft drinks (colas, etc.) were included only if a comparison to the above beverages was made.

- Outcomes: Any measure of dental hard tissue erosion, such as enamel surface softening, loss of surface hardness, profilometric enamel loss (μm), calcium or phosphate release, erosion depth, or standardized tooth wear indices (BEWE, VEDE, etc.). For clinical studies, a reported association between beverage intake and erosive wear indices or prevalence of ETW was required.

- Study types: In vitro laboratory studies, in situ studies (e.g. intraoral appliance experiments), clinical trials, observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, or case-control) and relevant case series. Both intervention studies (e.g. testing protective agents against erosion by these drinks) and observational data were included, though the primary focus was on the erosive impact of the beverages themselves.

- Investigated only intrinsic acid erosion (e.g. GERD or bulimia) with no focus on dietary/extrinsic acids.

- Focused solely on classic soft drinks or coffee/tea without including our “healthy beverage” categories (for example, a study comparing cola vs. orange juice vs. water would be included for the juice arm; but a study of cola vs. battery acid would be excluded as irrelevant).

- Examined erosion on restorative materials only (unless enamel/dentin results were also reported).

- Were case reports without measurement, expert opinion pieces, or not peer-reviewed.

- Non-English articles, unless a translation could be obtained (no such cases ultimately met criteria after screening).

Data Extraction

- For in vitro studies, we qualitatively noted methodological strengths/limits (e.g. use of human vs bovine enamel, presence of a remineralization phase to simulate saliva, number of cycles, etc.). Although no standardized tool exists for lab studies, we considered whether the model likely overestimates or underestimates erosion (e.g. continuous immersion for days vs. short cyclic exposure).

- For clinical/observational studies, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional studies (adapted) to judge selection bias, exposure assessment (e.g. quality of dietary questionnaire or beverage frequency data), outcome assessment (calibrated examiners for tooth wear indices), and control of confounders (did studies adjust for age, oral hygiene, intrinsic acids, etc.). Studies were graded as low, moderate, or high risk of bias. No studies were excluded based on quality, but risk of bias is considered in interpreting the results.

3. Results

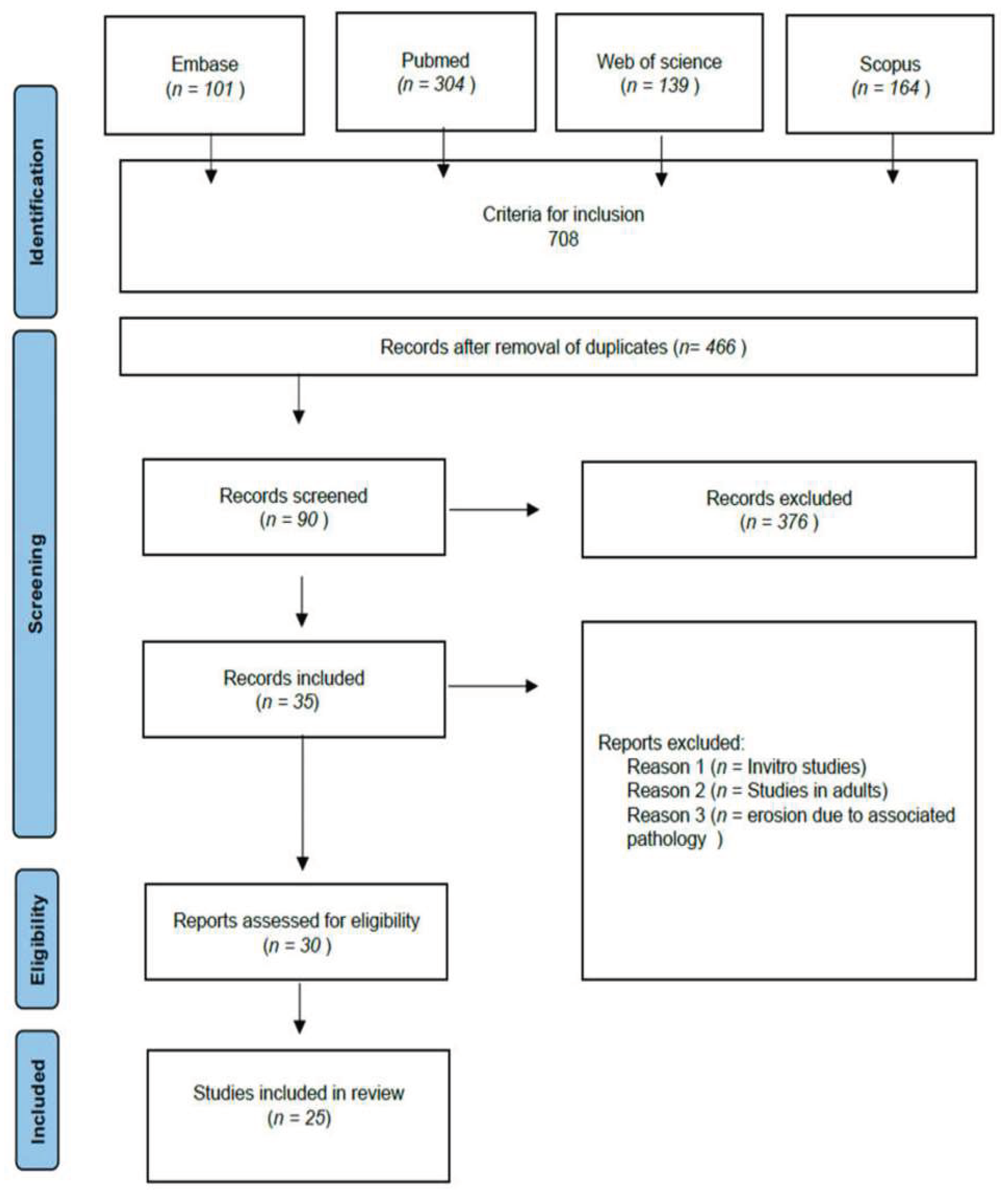

Study Selection

Study Characteristics

Behavioral and Usage Factors

- Frequency of intake: Individuals who sip acidic drinks many times a day (or continually throughout the day) are at much higher risk than those who have an occasional drink with meals [19, 23]. Many clinical studies show a dose-response: e.g. those drinking acidic beverages 2–3× daily had significantly higher odds of advanced tooth wear than those who consumed them <1× weekly. One study in young adults found those with “moderate/severe” wear consumed a median of 6 acidic drinks per day vs. 1 per day in those without wear [29]. Frequent sipping means constant acid exposure without sufficient time for saliva to neutralize and remineralize the enamel.

- Consumption method: Slow sipping or “swishing” the drink amplifies erosion. For example, holding a sports drink in the mouth and swishing (as some athletes do to prevent dryness) bathes the teeth in acid far longer than quickly drinking and swallowing. Instructing patients to avoid swishing acidic drinks and to use a straw positioned toward the back of the mouth can reduce contact with the teeth [29]. One in situ study demonstrated that using a straw markedly reduced erosion on anterior teeth as the liquid bypassed them.

- Timing relative to meals: Consuming acidic drinks between meals or at bedtime is riskier than with meals. Meals stimulate saliva (which buffers acid) and also often involve other foods that can partially neutralize acids. Many “healthy” drinks like lemon water or apple cider vinegar tonics are taken on an empty stomach in the morning – from a dental view, this is a worst-case scenario: unbuffered acid on teeth first thing in the morning when saliva flow is just ramping up. Studies advise that if acidic beverages are consumed, doing so with food or at least not right before brushing (to avoid brushing softened enamel) is prudent [29].

- Salivary factors: Saliva is a critical natural defense. It buffers acids and supplies calcium/phosphate to remineralize enamel. Individuals with low salivary flow (due to dehydration, exercise, or medical conditions) will experience more erosion. Athletes exercising vigorously may become temporarily xerostomic; combined with sports drink use, this creates a high-risk situation [21]. One survey of triathletes showed those who mouth-breathed during training and sipped sports drinks had significantly more tooth surface loss than those who mainly drank water. Good hydration and possibly using sugar-free gum to stimulate saliva after acidic drinks can help [29].

- Concurrent risk factors: The presence of other forms of tooth wear (attrition from grinding, abrasion from overbrushing) can exacerbate erosive damage. Erosion weakens and thins enamel, making teeth more susceptible to mechanical wear. Many included studies noted combined patterns. For instance, energy drink users who also had bruxism showed dramatically rapid enamel loss – acid softened the surfaces and grinding then abraded them easily. Likewise, swimmers in chlorinated pools (which can cause chemical erosion) who also drank acidic sports beverages had compounded effects.

- Misconceptions and behaviors: Some “health” fads inadvertently promote erosive habits – e.g. sipping lemon water or apple cider vinegar throughout the day for metabolism or detox benefits. Patients often do this unaware of dental consequences. One study found that among individuals aware of dental erosion, fewer (only ~40%) recognized that vitamin waters or sports drinks could harm teeth [1]. Education is lacking. Also, those aware of acidic foods sometimes still consume them in risky ways (perhaps believing brushing right after will solve it – which is actually contraindicated because brushing softened enamel accelerates wear).

Mitigation Strategies and Protective Factors

- Use of straws and quick ingestion: As noted, drinking through a straw positioned towards the throat can significantly reduce contact of the liquid with [28]. Similarly, finishing the drink relatively quickly (rather than sipping over hours) shortens the acid attack duration. Patients can be advised to consume their smoothie or sports drink in one go rather than over a long period.

- Rinsing with water or milk: Immediately after consuming an acidic beverage, rinsing the mouth with plain water can help wash away residual acids. Even better, drinking or rinsing with milk can neutralize acid – milk has a higher pH (~6.8) and calcium which can promote remineralization [5, 28]. One in situ study showed that ending an erosive challenge with a milk rinse or cheese snack helped recover enamel hardness faster. In children, those who drank milk regularly were found to have less erosion, supporting a protective effect [5].

- Delaying toothbrushing: Patients should be cautioned not to brush immediately after acidic drinks. The enamel surface will be softened for a time (studies suggest around 30 minutes to 1 hour for saliva to reharden it) [28]. Brushing in that window can abrade the softened enamel. It is recommended to wait at least 30–60 minutes before brushing after consuming acidic beverages. Alternatively, brushing beforehand (especially if a fluoride toothpaste is used to lay down some protection) and then just rinsing after the drink, is a safer routine.

- Fluoride and remineralizing agents: Frequent use of fluoride toothpaste (1,450 ppm) or higher-strength fluoride rinses can increase enamel resistance to acid. Stannous fluoride in particular has shown anti-erosion benefits by forming a protective SnF<sub>2</sub>-rich surface layer. Several included in situ studies (e.g. on sports drinks) demonstrated that fluoride pre-treatment significantly reduced enamel softening during acidic challenges [10]. Some products (toothpastes and mouthrinses) are specifically marketed for erosion control, often containing stannous fluoride or calcium phosphates. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) pastes have also been tested: results are mixed, but they can aid remineralization between acid exposures. For high-risk individuals (e.g. daily kombucha drinkers), prescribing a neutralizing rinse (like an alkaline mouthrinse or even baking soda in water) to use after the drink can help.

- Calcium fortification of beverages: From a product development standpoint, adding calcium to acidic drinks can lower their erosive potential. One included study fortified a fruit juice with calcium citrate malate (1000 mg/L) and observed a pH increase from 3.4 to 4.0 and a dramatic reduction in enamel calcium loss (by ~90%) [17]. The fortified juice caused much less enamel demineralization than the original juice. Another recent experiment (Dedhia et al. 2022) found that calcium-fortified beverages caused significantly less erosion in primary teeth than non-fortified equivalents. Some commercially available orange juices are calcium-fortified and indeed have slightly higher pH (~4.0) [17] and have been noted in literature to be less erosive. While fortifying all acidic drinks with calcium isn’t standard, it’s a promising approach. Manufacturers could consider reformulating sports drinks and energy drinks with calcium or other buffers to reduce harm. A caveat is that adding calcium may alter taste, but calcium citrate malate has been used successfully in juices for this purpose.

- Pellicle modification: The natural salivary pellicle on teeth can protect against erosion. Research is ongoing into boosting pellicle’s protective power (for example, using polyphenols or proteins that bind to enamel). One interesting finding: green tea and coffee, despite being acidic, have polyphenols that might form a protective film on enamel; but their net effect is still being studied. Some mouthrinse additives (like metal ions) can enhance pellicle defense. However, no specific pellicle-enhancing consumer product is on the market yet for erosion prevention [1].

- Patient education: A cornerstone of prevention is informing at-risk patients of the problem. Many included studies noted that knowledge gaps exist – even among health students – regarding which drinks cause erosion [1]. Dentists and hygienists should routinely ask about the intake of juices, sports and energy drinks, etc., particularly if they observe cupping on molars or incisal translucency. For patients who rely on these beverages (e.g. an athlete needing electrolytes or a diabetic using orange juice for lows), tailor advice to minimize harm (use of straw, rinse after, etc. as above rather than complete avoidance if not feasible).

- Alternative beverages: Encourage substitution of erosive drinks with non- or less-erosive options when possible. For hydration, water (plain water) is best (pH ~7). For caffeine, unsweetened coffee or tea (which are less acidic than soda/energy drinks, especially if a bit of milk is added) is preferable to energy drinks. If one enjoys carbonation, unflavored sparkling water is a safer alternative to cola. Some companies produce “tooth-friendly” sports drinks with reduced citric acid – these may be recommended if verified by research.

Summary of Evidence Quality

4. Discussion

Recommendations for Practice

- Identify at-risk patients: Those with early signs of erosion or those who report high intake of the beverages discussed. Ask specifically about sports drinks (many assume only sodas are harmful), energy drinks (which some might not mention unless prompted), and daily habits like hot water with lemon or vinegar cleanses.

- Provide personalized dietary counseling: Without demonizing patients’ choices, educate them on how these drinks affect teeth. Use analogies if helpful (e.g. “That sports drink is helping your muscles recover, but it’s like putting your teeth in an acid bath each time. Let’s find ways to reduce that effect.”).

- Recommend mitigation techniques: as detailed (straws, rinsing, not brushing immediately, fluoride use, etc.). For an athlete, something as simple as chewing sugar-free gum after a workout drink can stimulate saliva and reduce acid time.

- Consider topical interventions: For those unwilling or unable to change intake, more frequent application of remineralizing agents is warranted. Prescription high-fluoride toothpaste or custom trays with neutralizing gel (e.g. baking soda toothpaste in trays) might be useful in extreme cases.

- Monitor progression: Once identified, tooth wear should be monitored with study models or photos, so that any progression can be documented and addressed before requiring extensive restorations.

- Collaborate with patients’ physicians or coaches when appropriate: For example, if a patient is an athlete under nutritional guidance, a note to the team nutritionist about the dental findings and perhaps suggesting alternative hydration methods could be impactful.

Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmidt, J.; Huang, B. Awareness and knowledge of dental erosion and its association with beverage consumption: a multidisciplinary survey. BMC Oral Heal. 2022, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zero, D.T.; Lussi, A. Erosion — chemical and biological factors of importance to the dental practitioner. Int. Dent. J. 2005, 55, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni SS, Ehrlich Y, Hunke K, et al. The pH of beverages in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(4):255–263.

- American Dental Association (ADA). Dental Erosion. ADA Science & Research – Oral Health Topics. Updated Nov 2021. Available: https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/dental-erosion.

- Salas, M.; Nascimento, G.; Vargas-Ferreira, F.; Tarquinio, S.; Huysmans, M.; Demarco, F. Diet influenced tooth erosion prevalence in children and adolescents: Results of a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett ER, Bowsher J, Fillmore D, et al. Acids in sugar-free beverages could erode tooth enamel, research finds. ADA News (Science & Research Update). June 21, 2022.

- Okunseri, C.; Wong, M.C.M.; Yau, D.T.W.; McGrath, C.; Szabo, A. The relationship between consumption of beverages and tooth wear among adults in the United States. J. Public Heal. Dent. 2015, 75, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmassebi, J.F.; Kandiah, P.; Sukeri, S. The effects of fruit smoothies on enamel erosion. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 15, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind E, Lussi A, Hellwig E, et al. Erosive potential of ice tea beverages and kombuchas. Acta Odontol Scand. 2023;81(5):369–377.

- Lind, E.; Mähönen, H.; Latonen, R.-M.; Lassila, L.; Pöllänen, M.; Loimaranta, V.; Laine, M. Erosive potential of ice tea beverages and kombuchas. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.rdhmag.com/patient-care/article/16409422/only-part-of-the-story-the-danger-of-soft-drink-beverages-requires-a-closer-look-at-the-chemistry.

- Martínez, L.M.; Lietz, L.L.; Tarín, C.C.; García, C.B.; Tormos, J.I.A.; Miralles, E.G. Analysis of the pH levels in energy and pre-workout beverages and frequency of consumption: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Heal. 2024, 24, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlueter, N.; Amaechi, B.T.; Bartlett, D.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Carvalho, T.S.; Ganss, C.; Hara, A.T.; Huysmans, M.-C.D.; Lussi, A.; Moazzez, R.; et al. Terminology of Erosive Tooth Wear: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by the ORCA and the Cariology Research Group of the IADR. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali H, Tahmassebi JF. The effects of smoothies on enamel erosion: an in situ study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24(3):184–191.

- Zimmer, S.; Kirchner, G.; Bizhang, M.; Benedix, M. Influence of Various Acidic Beverages on Tooth Erosion. Evaluation by a New Method. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.news-medical.net/news/20220621/Acids-in-sugar-free-beverages-could-erode-tooth-enamel-research.

- Franklin, S.; Masih, S.; Thomas, A.M. An in-vitro assessment of erosive potential of a calcium-fortified fruit juice. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 15, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhart SD, Yunker M, Lill GE, et al. The erosive potential of sugar-free beverages on cervical dentin. JADA Found Sci. 2022;1(2):100009.

- Memon MA, Adekunle AO, Razak PA, et al. Sports Drinks and Dental Erosion: Unveiling the Evidence from a Systematic Review. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2025;(in press): [Epub ahead of print].

- Cruz-Gonzales G, Paredes-Rodríguez VM, González-Aragón Pineda ÁE, et al. Erosive Potential of Sports, Energy Drinks, and Isotonic Solutions on Athletes’ Teeth: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025;17(3):403.

- Memon, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, M.; Tariq, I.; Younus, K.; Aleem, B.; Lee, K.Y. Sports Drinks and Dental Erosion: Unveiling the Evidence from a Systematic Review. Curr. Oral Heal. Rep. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, M.; Nascimento, G.; Vargas-Ferreira, F.; Tarquinio, S.; Huysmans, M.; Demarco, F. Diet influenced tooth erosion prevalence in children and adolescents: Results of a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okunseri, C.; Wong, M.C.M.; Yau, D.T.W.; McGrath, C.; Szabo, A. The relationship between consumption of beverages and tooth wear among adults in the United States. J. Public Heal. Dent. 2015, 75, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacker, S.M.; Chadwick, R.G. An in vitro investigation of the erosive potential of smoothies. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 214, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surarit, R.; Jiradethprapai, K.; Lertsatira, K.; Chanthongthiti, J.; Teanchai, C.; Horsophonphong, S. Erosive potential of vitamin waters, herbal drinks, carbonated soft drinks, and fruit juices on human teeth: An in vitro investigation. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2023, 17, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.rdhmag.com/patient-care/article/16409422/only-part-of-the-story-the-danger-of-soft-drink-beverages-requires-a-closer-look-at-the-chemistry.

- Gálvez-Bravo, F.; Edwards-Toro, F.; Contador-Cotroneo, R.; Opazo-García, C.; Contreras-Pulache, H.; Goicochea-Palomino, E.A.; Cruz-Gonzales, G.; Moya-Salazar, J. Erosive Potential of Sports, Energy Drinks, and Isotonic Solutions on Athletes’ Teeth: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Martins, J.; de Sousa, E.; Fernandes, N.; Meira, I.; Sampaio, F.; de Oliveira, A.; Pereira, A. Influence of energy drinks on enamel erosion: In vitro study using different assessment techniques. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e1076–e1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; Azzollini, D.; Trilli, I.; Carpentiere, V.; Hazballa, D.; Bordea, I.R.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M. Advances in Preventive and Therapeutic Approaches for Dental Erosion: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; Norris, D.F.; Momeni, S.S.; Waldo, B.; Ruby, J.D. The pH of beverages in the United States. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71.

- Pineda, Á.E.G.-A.; Borges-Yáñez, S.A.; Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.; Lussi, A. Relationship between erosive tooth wear and beverage consumption among a group of schoolchildren in Mexico City. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 23, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.; Masih, S.; Thomas, A.M. An in-vitro assessment of erosive potential of a calcium-fortified fruit juice. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 15, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedhia, P.; Pai, D.; Shukla, S.D.; Anushree, U.; Kumar, S.; Pentapati, K.C. Analysis of Erosive Nature of Fruit Beverages Fortified with Calcium Ions: An In Vitro Study Evaluating Dental Erosion in Primary Teeth. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.S.; Colon, P.; Ganss, C.; Huysmans, M.C.; Lussi, A.; Schlueter, N.; Schmalz, G.; Shellis, R.P.; Tveit, A.B.; Wiegand, A. Consensus report of the European Federation of Conservative Dentistry: erosive tooth wear—diagnosis and management. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1557–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulic, A.; Skudutyte-Rysstad, R.; Tveit, A.B.; Skaare, A.B. Risk indicators for dental erosive wear among 18-yr-old subjects in Oslo, Norway. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012, 120, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Nihill, P.; Sobkowski, J.; Agustin, M.Z. Commercial soft drinks: pH and in vitro dissolution of enamel. Gen Dent. 2007, 55, 150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Inage, H.; Kawamoto, R.; Tonegawa, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Tsubota, K.; Takamizawa, T.; Miyazaki, M. Ultrasonic monitoring of the setting of glass–ionomer luting cements. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 116, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussi, A.; Hellwig, E.; Zero, D.; Jaeggi, T. Erosive tooth wear: diagnosis, risk factors and prevention. Am J Dent.. 2006, 19, 319–25. [Google Scholar]

- Buzalaf MAR, Magalhães AC, Rios D. Preventive measures for dental erosion. In: Lussi A, Ganss C (eds). Dental Erosion: Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, Treatment. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;25:338–352.

- El Aidi H, Bronkhorst EM, Huysmans MC, Truin GJ. Stages in the progression of erosive tooth wear in adolescents: a 3-year longitudinal study. Caries Res. 2010;44(2):129–134.

- Bartlett D, O’Toole S. Prevalence of tooth wear and the role of erosive diet in the aging population. J Dent. 2019;87:101013.

| Beverage Category | Typical pH (range) | Titratable Acidity (TA)<sup>†</sup> | Relative Erosive Potential<sup>‡</sup> |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit Juices (100%) | 3.0 – 3.8 (often ~3.5) | High – e.g. ~10–20 ml NaOH to neutralize 100 ml<sup>§</sup> (varies by juice) | High (contains citric/malic acids; can soften enamel quickly; some juices as erosive as sodas) [17] |

| Fruit Smoothies | 3.5 – 4.0 | Very High – e.g. requires ~3–4× more base than cola to neutralize | High (erosive in vitro similar or greater than cola; prolonged fruit acid exposure) [8] |

| Vitamin Waters | 3.1 – 3.8 | Moderate/High – buffered by citric acid (TA higher than plain water, less than pure juice) | Moderate–High (cause enamel weight loss in vitro; slightly less than fruit juices in one study) [18] |

| Herbal/Iced Teas | 2.7 – 5.5 (sweetened bottled teas often 3.0–3.5) | Variable – depends on added acids (e.g. lemon tea high TA, vs. neutral teas) | Moderate (unsweetened teas low erosive potential, but lemon/hibiscus teas can be High, comparable to colas) [10] |

| Kombucha (fermented tea) | 2.5 – 3.5 | High – contains acetic and gluconic acids (buffering capacity considerable) | High (in vitro Ca release and enamel erosion considerable, often more than cola) [10] |

| Sports Drinks (isotonic) | 3.2 – 4.0 (typical ~3.5) | High – typically formulated with citric acid (TA similar to juices) | High (known to cause enamel softening; frequent use linked to ETW in athletes ) [18, 19] |

| Energy Drinks | 2.5 – 3.7 (many ~3.1) | Very High – multiple acids (citric, phosphoric); e.g. Red Bull TA ≈ 52 vs. Coke 18 (arbitrary units) | High (most erosive category in many studies; in vitro enamel loss 2× that of sports drinks in one report) [20] |

| Carbonated Water (plain) | ~5.0 – 5.5 | Very Low – carbonic acid weakly buffered (little base needed to neutralize) | Low (minimal enamel effects if unflavored; saliva can readily neutralize) [18] |

| Flavored Sparkling Water | 3.0 – 4.0 | Moderate – often contains citric acid flavoring (some buffering) | Moderate (demonstrable enamel softening in vitro, though less than soda; prolonged exposure can contribute to wear) [18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).