Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

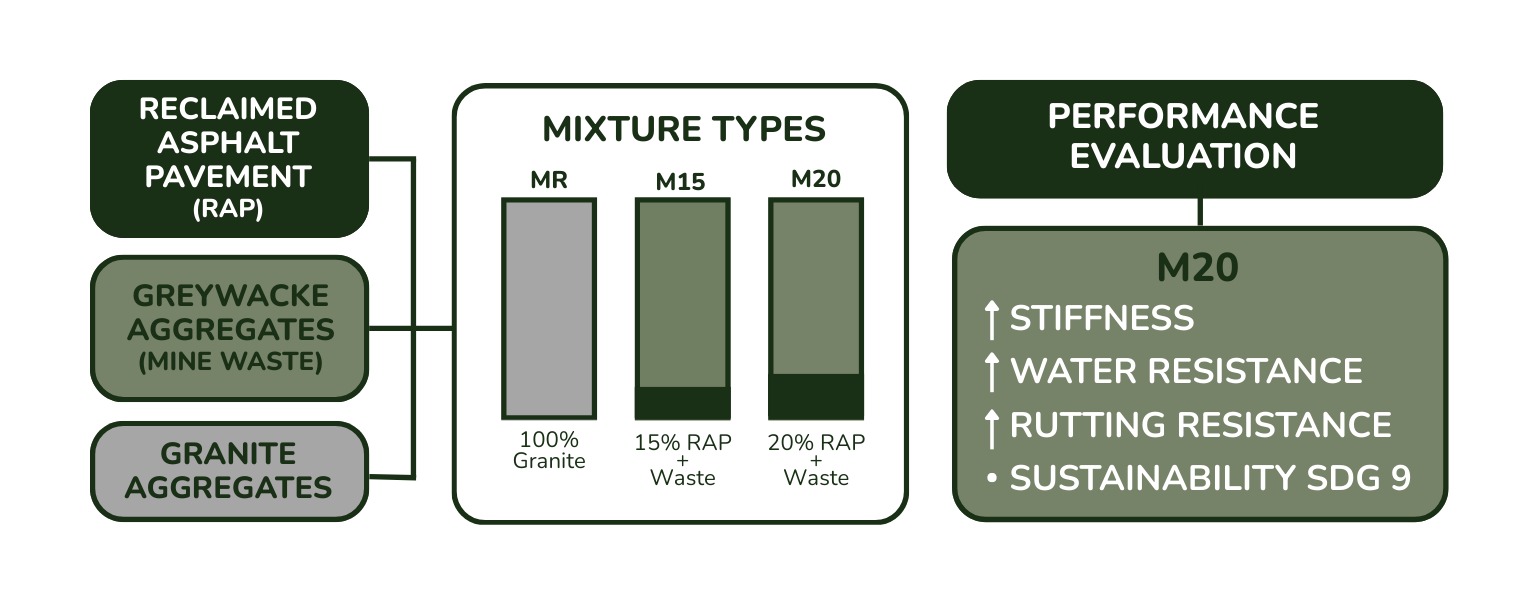

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Bitumen

2.1.2. Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP)

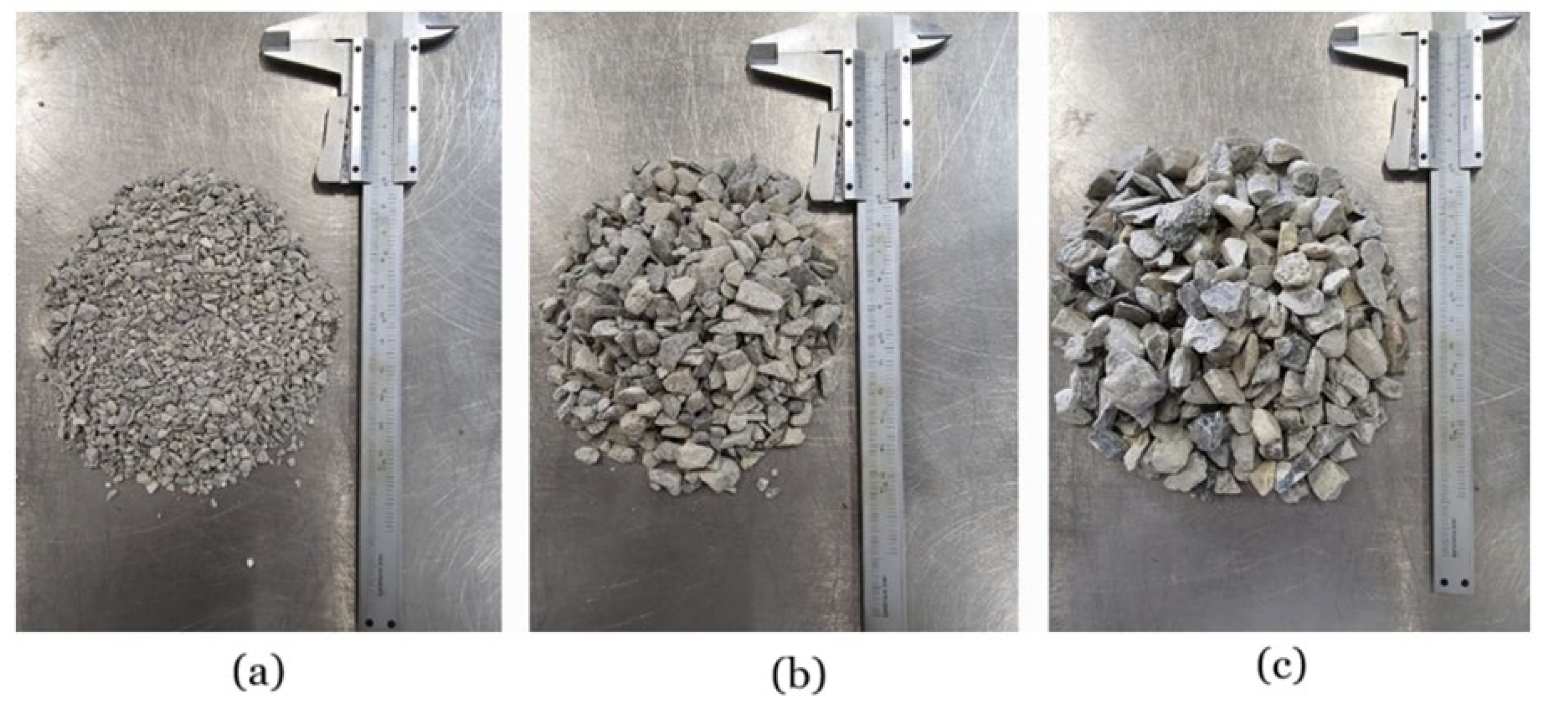

2.1.3. Natural and Waste Aggregates

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Optimum Bitumen Content

2.2.2. Stiffness Modulus

2.2.3. Water Sensitivity

2.2.4. Resistance to permanent deformation

3. Results

3.1. Stiffness Modulus

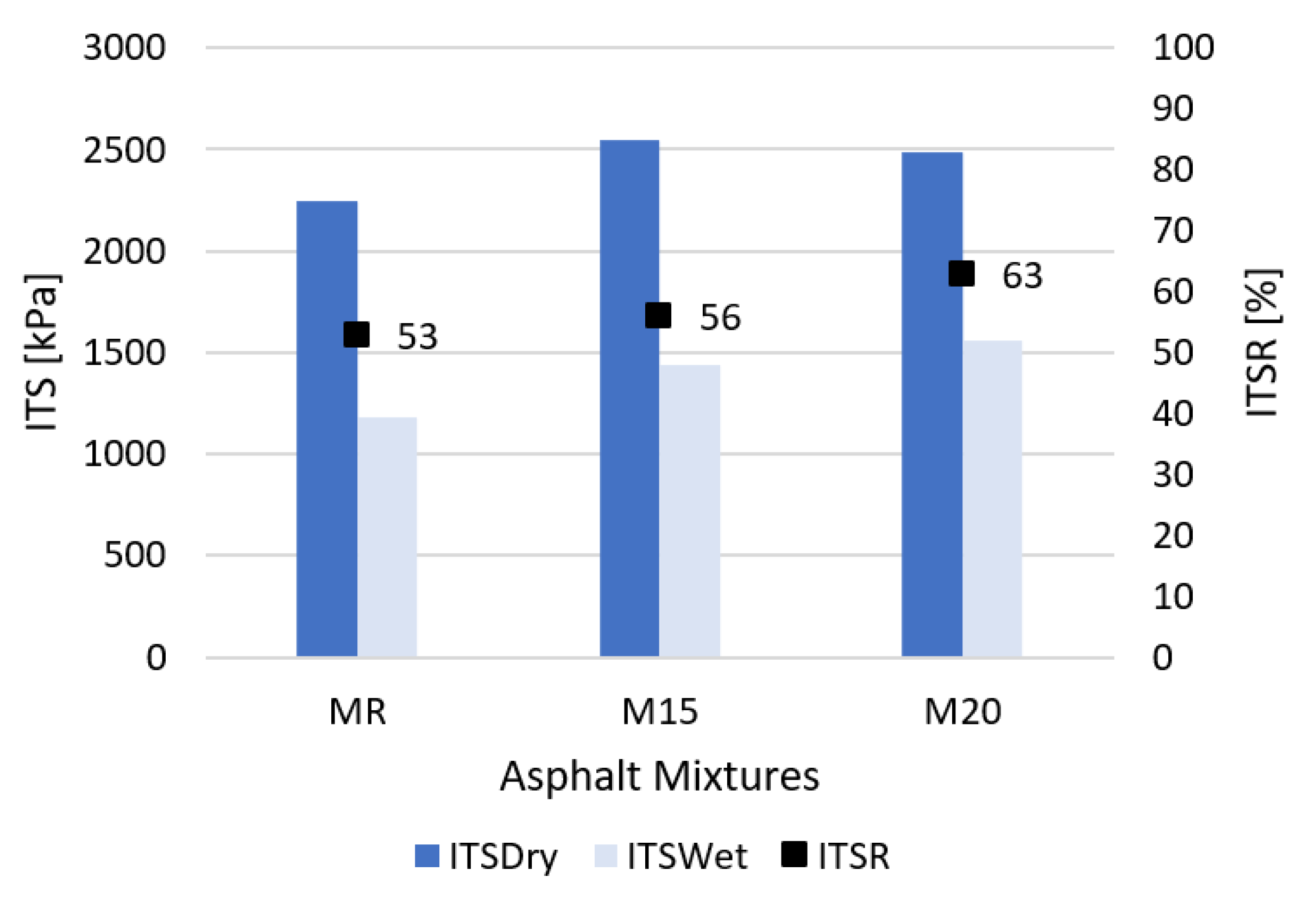

3.2. Water Sensitivity

3.3. Resistance to Permanent Deformation

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Stiffness Modulus: The incorporation of RAP significantly increased the stiffness of asphalt mixtures compared to the reference mixture (MR), due to the aged bitumen’s lower penetration and reduced elasticity.

- (2)

- Water Sensitivity: The addition of RAP improved the indirect tensile strength (ITS) under both dry and wet conditions. This enhancement indicates better moisture resistance and overall mechanical integrity of the RAP-modified mixtures.

- (3)

- Permanent Deformation: The M20 mixture demonstrated the lowest rut depth and wheel tracking slope values, showing the best resistance to permanent deformation among the mixtures tested.

- (4)

- Optimal Design: Among the evaluated mixtures, M20 emerged as the most promising solution in terms of mechanical performance, water resistance, and dimensional stability, fully complying with Portuguese road specifications.

References

- J. Choudhary, B. Kumar and A. Gupta, “Utilization of solid waste materials as alternative fillers in asphalt mixes: A review,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 234, p. 117271, 2020.

- A. Raposeiras, D. Movilla, O. Muñoz and M. Lagos, “Production of asphalt mixes with copper industry wastes: Use of copper slag as raw material replacement,” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 293, p. 112867, 2021.

- Y. Sun, X. Zhang, J. Chen, J. Liao and C. Shi, “Mixing design and performance of porous asphalt mixtures containing solid waste,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 21, 2024.

- M. G. López Domínguez, A. Pérez Salazar e P. Garnica Anguas, “Estado del arte sobre el uso de residuos y sub productos industriales en la construcción de carreteras,” Instituto Mexicano del Transporte ISSN 0188 - 7297, 2014.

- P. Kumar Gautam, K. Pawan, A. Singh Jethoo, R. Agrawal e H. Singh, “Sustainable use of waste in flexible pavement: A review,” Construction and Bulding Materials, nº 180, pp. 239 - 253, 2018.

- W. Victory, “A review on the utilization of waste material in asphalt pavements,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 29, p. 27279–27282, 2022.

- H.-H. Chu, A. Almohana, G. QasMarrogy, S. Almojil, A. Alali, K. Almoalimi and A. Raise, “Experimental investigation of performance properties of asphalt binder and stone matrix asphalt mixture using waste material and warm mix additive,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 368, no. 130397, p. 130397, 2023.

- A. Mahpour, S. Alipour, M. Khodadadi, A. Khodaii and J. Absi, “Leaching and mechanical performance of rubberized warm mix asphalt modified through the chemical treatment of hazardous waste materials,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 366, no. 130184, p. 130184, 2023.

- K. Zhang, W. Zhang, W. Xie, Y. Luo and G. Wei, “Investigation of mechanical properties, chemical composition and microstructure for composite cementitious materials containing waste powder recycled from asphalt mixing plants.,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 96, p. 110362, 2024.

- L. Riberito de Reznede, L. Ramos da Silveira, W. Lima de Araújo e M. Pereira da Luz, “Reuse of Fine Quarry Wastes in Pavement: Case Study in Brazil,” Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 26, nº 8, 2013.

- M. O. Marques, N. L. Cunha and L. R. Rezende, “The use of non-conventional materials in asphalt pavements base,” Road Materials and Pavement Design, vol. 16, pp. 799-814, 2015.

- J. Neves and A. Freire, “Special Issue “The Use of Recycled Materials to Promote Pavement Sustainability Performance”,” MDPI, vol. 7, p. 12, 2022.

- W. Zhao e Q. Yang, “Life-cycle assessment of sustainable pavement based on the coordinated application of recycled asphalt pavement and solid waste: Environment and economy,” Clener Production, 2023.

- M. Barral, J. A. Navarro, A. García Siller e M. Cembrero, “Experiencia en obra con una mezcla bituminosa reciclada templada con alta tasa de material de fresado,” CEPSA, 2023.

- M. Dinis-Almeida, J. Gomes, C. Sangiorgi, S. Zoorob and M. Afonso, “Performance of Warm Mix Recycled Asphalt containing up to 100% RAP,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 112, pp. 1 - 6, 2016.

- D. -. H. Kang, S. Gupta, A. Z. Ranaivoson, J. Siekmeier e R. Roberson, “Recycled Materials as Substitutes for Virgin Aggregates in Road Construction: I. Hydraulic and Mechanical Characteristics,” Soil Science Society of America Journal, vol. 75, pp. 1265-1275, 2011.

- Y. Yao, J. Yang, J. Gao, M. Zheng, J. Xu, W. Zhang and L. Song, “Strategy for improving the effect of hot in-place recycling of asphalt pavement,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 366, p. 130054, 2023.

- P. N. Khosla, H. Nair, B. Visintine e G. Malpass, “Effect of Reclaimed Asphalt and Virgin Binder on Rheological Properties of Binder Blends,” International Journal of pavement research and technology, vol. 5, nº 5, pp. 317-325, 2012.

- J. Oliver, “The Influence of the Binder in RAP on Recycled Asphalt Properties,” Road Materials and Pavement Design, vol. 2, pp. 311-325, 2001.

- H. Zhong, W. Huang, C. Yan, Y. Chang, Q. Lv, L. Sun and L. Liu, “Investigating binder aging during hot in-place recycling (HIR) of asphalt pavement,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 276, p. 122188, 2021.

- K. Kaur, A. Krishna and A. Das, “Constituent Proportioning in Recycled Asphalt Mix with Multiple RAP Sources,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 104, pp. 21-28, 2012.

- R. Karlsson and U. Isacsson, “Material-Related Aspects of Asphalt Recycling—State-of-the-Art,” Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 18, 2006.

- Y. Liu, H. Wang, S. Tighe, D. Pickel and Z. You, “Study on impact of variables to pavement preheating operation in HIR by using FEM,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 243, p. 118304, 2020.

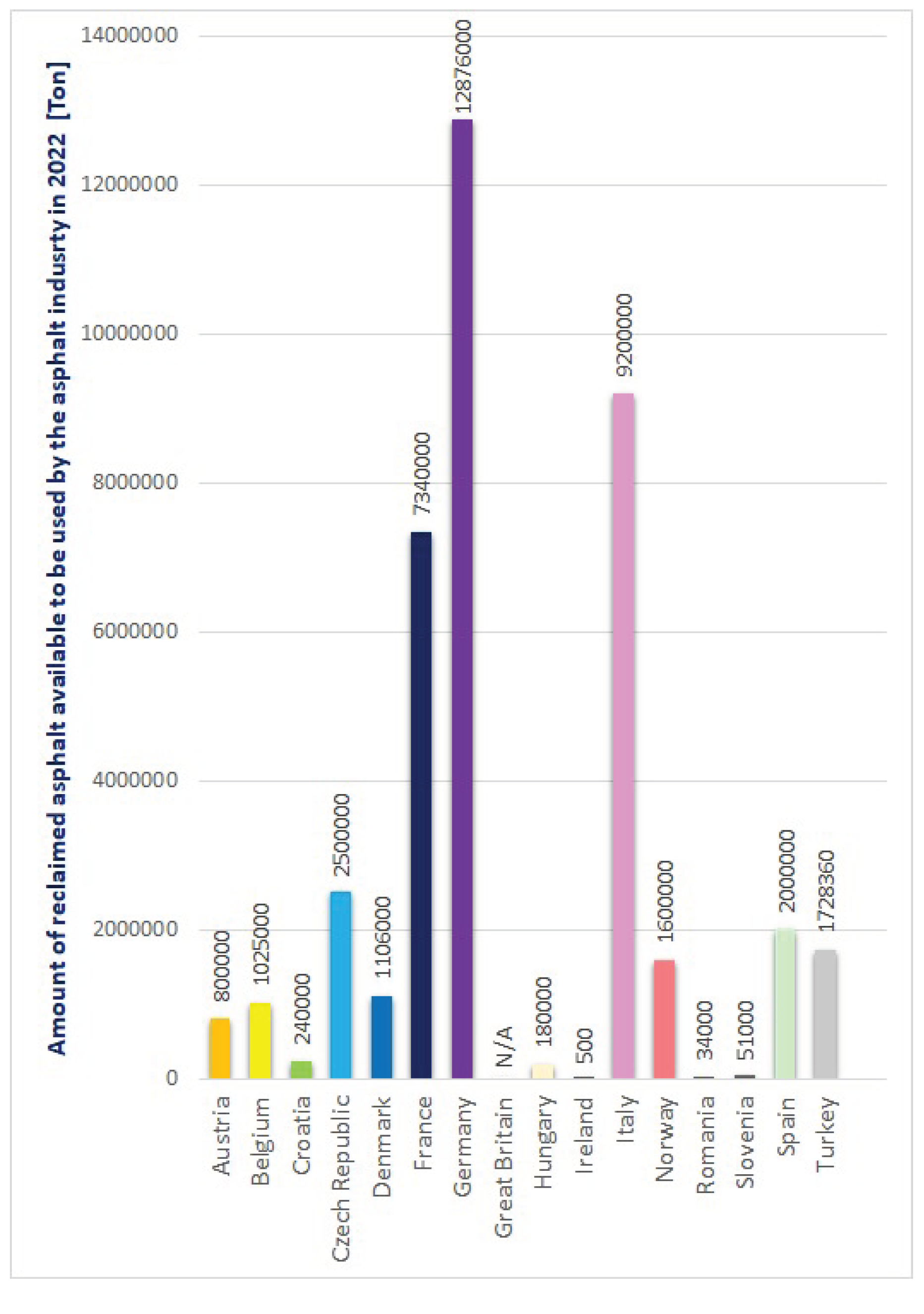

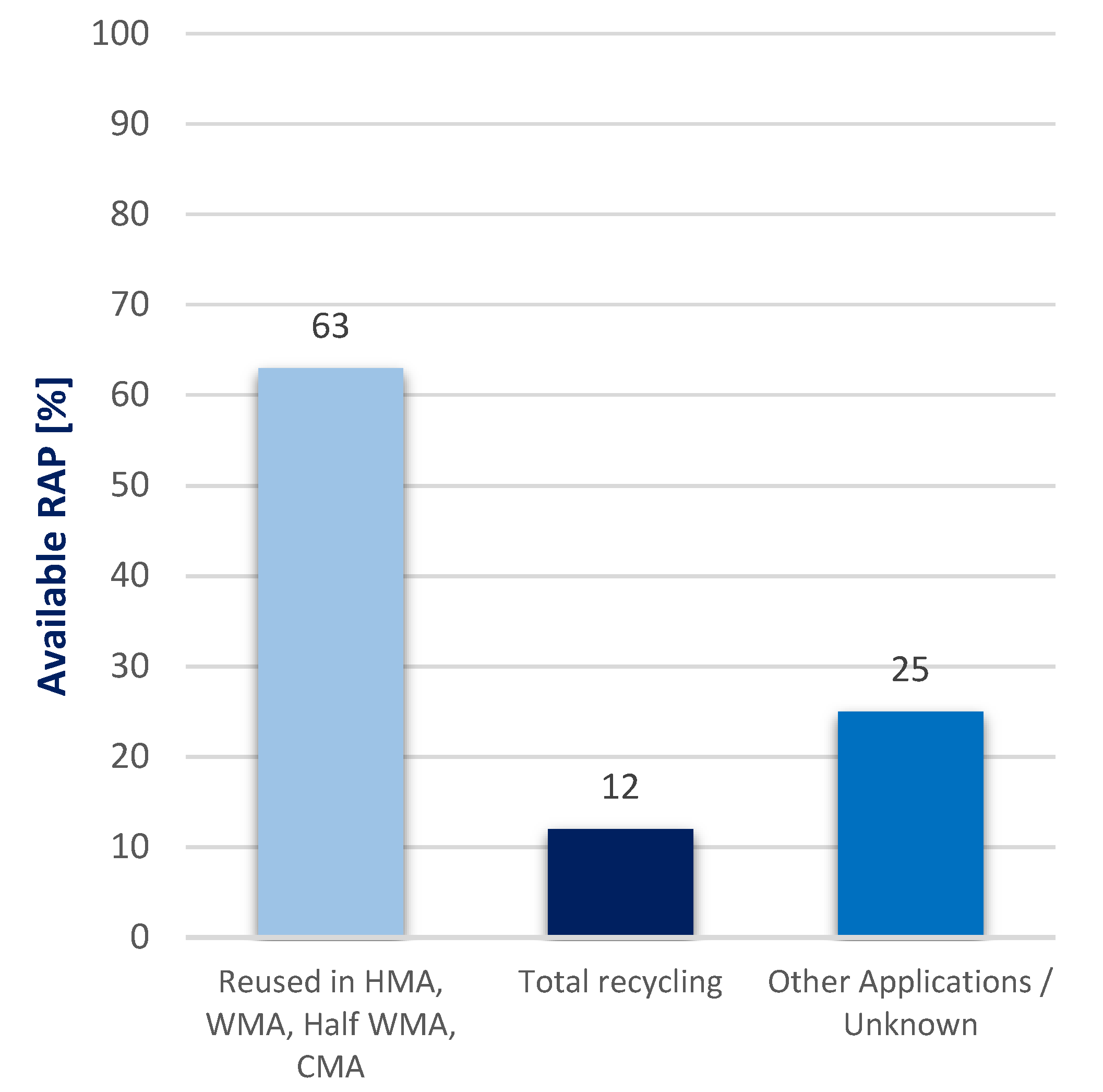

- EAPA, “EAPA Asphalt in Figures 2022,” 2022.

- M. Nandal, H. Sood e P. Kumar Gupta, “A review study on sustainable utilisation of waste in bituminous layers of flexible pavement,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 19, 2023.

- Y. Chen, Z. Chen, Q. Xiang, W. Qin and J. Yi, “Research on the influence of RAP and aged asphalt on the performance of plant-mixed hot recycled asphalt mixture and blended asphalt,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 15, 2021.

- G. Masi, A. Michelacci, S. Manzi and M. Bignozzi, “Assessment of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) as recycled aggregate for concrete,” Construction and Builgind Materials, vol. 341, p. 127745, 2022.

- G. Blight, “Chapter 5 - Mine Waste: A Brief Overview of Origins, Quantities, and Methods of Storage,” Waste, pp. 77 - 88, 2011.

- P. Segui, A. Mahdi, M. Amrani and M. Benzaazoua, “Mining Wastes as Road Construction Material: A Review,” MDPI, vol. 13, p. 90, 2023.

- P. Ávila, E. Ferreira, A. Salgueiro and J. Jarinha, “Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Mill Tailings Impoundments from the Panasqueira Mine (Portugal): Implications for the Surrounding Environment,” Mine Water and the Environment, pp. 210 - 224, 2008.

- C. Marignac, M. Cuney, M. Cathelineau, E. Carocci and F. Pinto, “The Panasqueira Rare Metal Granite Suites and Their Involvement in the Genesis of the World-Class Panasqueira W–Sn–Cu Vein Deposit: A Petrographic, Mineralogical, and Geochemical Study,” MDPI - Minerals, p. 562, 2020.

- Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, “Jóias da Terra: o minério da Panasqueira,” 2004. [Online]. Available: https://museus.ulisboa.pt/joias-da-terra-o-o-minerio-da-panasqueira.

- M. Maia, M. Dinis-Almeida and F. Martinho, “The Influence of the Affinity between Aggregate and Bitumen on the Mechanical Performance Properties of Asphalt Mixtures,” MDPI - Materials, vol. 14, 2021.

- Estradas de Portugal, S.A., “Caderno de Encargos Tipo Obra (CETO), 14.03 - Pavimentação Características dos materiais,” 2014. [Online]. Available: https://servicos.infraestruturasdeportugal.pt/pdfs/infraestruturas/14_03_set_2014.pdf. [Accessed 8 August 2024].

- M. Dinis-Almeida and M. Afonso, “Warm Mix Recycled Asphalt – a sustainable solution,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 107, pp. 310-316, 2015.

| Sieve size [mm] |

Cumulative Passing [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granite aggregates | Greywacke aggregates | RAP | Hydraulic lime | ||||

| Stone Dust | Gravel 8/16 | Stone Dust | Gravel 2/10 |

Gravel 8/14 | |||

| 20 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 14 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 98 | 100 |

| 10 | 100 | 61 | 100 | 96 | 37 | 91 | 100 |

| 4 | 100 | 7 | 93 | 17 | 1 | 74 | 100 |

| 2 | 85 | 5 | 41 | 3 | 1 | 56 | 100 |

| 0,5 | 44 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 100 |

| 0,125 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 100 |

| 0,063 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Aggregate | MR | M15 | M20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Stone Dust | 35 | - | - |

| Natural Gravel 8/16 | 62 | - | - |

| Greywacke stone dust | - | 28 | 20 |

| Greywacke Gravel 2/10 | - | 16 | 17 |

| Greywacke Gravel 8/14 | - | 35 | 35 |

| Hydraulic lime | 3 | 6 | 8 |

| RAP | - | 15 | 20 |

| Bituminous mixtures | Bitumen [%] | Bulk density [kg/m3] | Marshall Stability [kN] | Marshall flow [mm] |

Marshall quotient [kN/mm] | VMA [%] |

Porosity [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | 5,2 | 2340 | 17,1 | 3,1 | 5,6 | 16,9 | 5,1 |

| M15 | 4,4 | 2448 | 13,7 | 4,3 | 3,2 | 15,3 | 4,8 |

| 3,9 | 2430 | 14,2 | 3,0 | 4,8 | 16,6 | 6,4 | |

| 3,4 | 2393 | 12,1 | 2,9 | 4,2 | 18,6 | 8,4 | |

| M20 | 4,4 | 2464 | 12,6 | 2,7 | 4,6 | 14,2 | 3,7 |

| 3,9 | 2450 | 13,1 | 3,3 | 4,0 | 15,5 | 5,0 | |

| 4,9 | 2475 | 11,7 | 3,7 | 3,2 | 13,1 | 2,5 | |

| Portuguese road requirements | - | - | 7,5 – 15 | 2 – 4 | >3 | Min 14 | 3 – 5 |

| Bituminous mixtures | % Bitumen | Stiffness Modulus [MPa] |

|---|---|---|

| MR | 5,2 | 7195 |

| M15 | 4,4 | 11343 |

| M20 | 4,4 | 11739 |

| Asphalt mixtures | Bitumen [%] | RD [mm] | WTS [mm/103 cycles] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | 5,2 | 5,9 | 0,31 | |

| M15 | 4,4 | 9,6 | 0,80 | |

| M20 | 4,4 | 3,3 | 0,19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).