Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacers |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Pb | Lead |

| MLP | Maximum Permissible Limits |

| IC50 | Half maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| bp | Base Pair |

References

- M. H. Wong, “Ecological restoration of mine degraded soils, with emphasis on metal contaminated soils,” Chemosphere, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 775–780, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Covarrubias, J. A. García Berumen, and J. J. Peña Cabriales, “Microorganisms role in the bioremediation of contaminated soils with heavy metals,” Acta Univ., vol. 25, no. NE-3, pp. 40–45, 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. García Aguirre, “La minería en México,” Espac. para el Cap. a cielo abierto, INEGI, pp. 128–136, 2012, Available: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/124/12426062013.pdf.

- O. A. Flores-Amaro et al., “Characterization and evaluation of the bioremediation potential of Rhizopus microsporus Os4 isolated from arsenic-contaminated soil,” Water. Air. Soil Pollut., vol. 235, no. 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- DOF, NORMA OFICIAL MEXICANA NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004, Que establece criterios para determinar las concentraciones de remediación de suelos contaminados por arsénico, bario, cadmio, cromo hexavalente, mercurio, níquel, plata, selenio, talio y/o vanadio. 2007, pp. 35–96. Available: http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/libros/402/cuencas.html.

- S. A. Covarrubias and J. J. Peña Cabriales, “Contaminación ambiental por metales pesados en México: Problemática y estrategias de fitorremediación,” Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient., vol. 33, pp. 7–21, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Sep, “Toxicological Profile for Cadmium,” ATSDR’s Toxicol. Profiles, no. September, 2002. [CrossRef]

- L. Newsome and C. Falagán, “The Microbiology of Metal Mine Waste: Bioremediation Applications and Implications for Planetary Health,” GeoHealth, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 1–53, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Tian et al., “A new insight into lead (II) tolerance of environmental fungi based on a study of Aspergillus niger and Penicillium oxalicum,” Environ. Microbiol., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 471–479, 2019. [CrossRef]

- FAO & ITPS, Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR) – Technical Summary. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation and Intergovernmental echnical Panel on Soils, Rome, Italy. 2015. Available: http://www.fao.org/3/i5126e/i5126e.pdf link accessed on 28/04/2020.

- I. E. García, “Microorganismos del suelo y sustentabilidad de los agroecocistemas,” Rev. Argent. Microbiol., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 1–3, 2011, Available: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2130/213019226001.pdf.

- J. A. Samaniego-Gaxiola and Y. Chew-Madinaveitia, “Diversidad de géneros de hongos del suelo en tres campos con diferente condición agrícola en La Laguna, México,” Rev. Mex. Biodivers., vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 383–390, 2007.

- M. Delgado, “Los microorganismos del suelo en la nutrición vegetal,” Investig. ORIUS Biotecnol., pp. 1–9, 2008, Available: https://portalcamaronero.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Los-microorganismos-del-suelo-en-la-nutrición-vegetal.pdf.

- E. P. Burford, M. Fomina, and G. M. Gadd, “Fungal involvement in bioweathering and biotransformation of rocks and minerals,” Mineral. Mag., vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 1127–1155, 2003. [CrossRef]

- X. Yu and Q. Zhan, “Phosphate-Mineralization Microbe Repairs Heavy Metal Ions That Formed Nanomaterials in Soil and Water,” Nanomater. - Toxicity, Hum. Heal. Environ., pp. 3–9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., “Microbial controls on heavy metals and nutrients simultaneous release in a seasonally stratified reservoir,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1937–1948, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Ayangbenro and O. O. Babalola, “A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: A review of microbial biosorbents,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Qiu et al., “Experimental and modeling studies of competitive Pb (II) and Cd (II) bioaccumulation by Aspergillus niger,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 105, no. 16–17, pp. 6477–6488, 2021. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11497-3. [CrossRef]

- A. Kapoor, T. Viraraghavan, and D. R. Cullimore, “Removal of heavy metals using the fungus Aspergillus niger,” Bioresour. Technol., vol. 70, pp. 95–104, 1999.

- S. E. Hassan, M. Hijri, and M. St-Arnaud, “Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on trace metal uptake by sunflower plants grown on cadmium contaminated soil,” N. Biotechnol., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 780–787, 2013. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2013.07.002. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, H. Luo, Z. Du, L. Hu, and J. Fu, “Identification of cadmium-resistant fungi related to Cd transportation in bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers.],” Chemosphere, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 786–792, 2014. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.10.037. [CrossRef]

- M. Refaey, A. M. Abdel-Azeem, H. H. Abo Nahas, M. A. Abdel-Azeem, and A. A. El-Saharty, Role of Fungi in Bioremediation of Soil Contaminated with Heavy Metals, no. June. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Bonifaz Trujillo, Micología Médica Básica, Cuarta. Ciudad de Mexico: Mc Graw-Hill, 2012. Available: https://mega.nz/folder/UR0D0YwL#eRPcO3H4VRhMrkJeVBtUoA.

- C. L. Văcar et al., “Heavy metal-resistant filamentous fungi as potential mercury bioremediators,” J. Fungi, vol. 7, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Janicki, J. Długoński, and M. Krupiński, “Detoxification and simultaneous removal of phenolic xenobiotics and heavy metals with endocrine-disrupting activity by the non-ligninolytic fungus Umbelopsis isabellina,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 360, pp. 661–669, 2018. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.047. [CrossRef]

- M. Le Berre, J. Q. Gerlach, I. Dziembała, and M. Kilcoyne, “Calculating Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) Values from Glycomics Microarray Data Using GraphPad Prism,” Methods Mol. Biol., vol. 2460, pp. 89–111, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Rangel-Muñoz et al., “Assessment of the Potential of a Native Non-Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus Isolate to Reduce Aflatoxin Contamination in Dairy Feed,” Toxins (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Aljanabi and I. Martinez, “Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 25, pp. 4692–4693, 1997.

- J. Sambrook and D. . Russell, Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed., vol. 2. New York: Cold Sring Harbor Labratory, 2001. [CrossRef]

- D. Gola, A. Malik, M. Namburath, and S. Z. Ahammad, “Removal of industrial dyes and heavy metals by Beauveria bassiana: FTIR, SEM, TEM and AFM investigations with Pb(II),” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 25, no. 21, pp. 20486–20496, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Luo, S. Qiang, R. Geng, L. Shi, J. Song, and Q. Fan, “Mechanistic study for mutual interactions of Pb2+ and Trichoderma viride,” Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., vol. 233, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Chen, S. L. Ng, Y. L. Cheow, and A. S. Y. Ting, “A novel study based on adaptive metal tolerance behavior in fungi and SEM-EDX analysis,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 334, pp. 132–141, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. R. Noormohamadi, M. R. Fat’hi, M. Ghaedi, and G. R. Ghezelbash, “Potentiality of white-rot fungi in biosorption of nickel and cadmium: Modeling optimization and kinetics study,” Chemosphere, vol. 216, pp. 124–130, 2019. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.113. [CrossRef]

- F. Ye, D. Gong, C. Pang, J. Luo, X. Zeng, and C. Shang, “Analysis of Fungal Composition in Mine-Contaminated Soils in Hechi City,” Curr. Microbiol., vol. 77, no. 10, pp. 2685–2693, 2020. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02044-w. [CrossRef]

- Z. Deng et al., “Characterization of Cd- and Pb-resistant fungal endophyte Mucor sp. CBRF59 isolated from rapes (Brassica chinensis) in a metal-contaminated soil,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 185, no. 2–3, pp. 717–724, 2011. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.078. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Salazar et al., “Pb accumulation in spores of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 643, pp. 238–246, 2018. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.199. [CrossRef]

- A. Sagar, R. Riyazuddin, P. K. Shukla, P. W. Ramteke, and R. Z. Sayyed, “Heavy metal stress tolerance in Enterobacter sp. PR14 is mediated by plasmid,” Indian J. Exp. Biol., vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 115–121, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Budamagunta et al., “Nanovesicle and extracellular polymeric substance synthesis from the remediation of heavy metal ions from soil,” Environ. Res., vol. 219, p. 114997, Feb. 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013935122023246. [Accessed: Apr. 24, 2025]. [CrossRef]

- H. Naz et al., “Mesorhizobium improves chickpea growth under chromium stress and alleviates chromium contamination of soil,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 338, p. 117779, Jul. 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479723005674?via%3Dihub. [Accessed: Apr. 24, 2025]. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Urquhart, N. F. Chong, Y. Yang, and A. Idnurm, “A large transposable element mediates metal resistance in the fungus Paecilomyces variotii,” Curr. Biol., vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 937-950.e5, 2022. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.048. [CrossRef]

- M. Słaba, E. Gajewska, P. Bernat, M. Fornalska, and J. Długoński, “Adaptive alterations in the fatty acids composition under induced oxidative stress in heavy metal-tolerant filamentous fungus Paecilomyces marquandii cultured in ascorbic acid presence,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 3423–3434, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Zeng, J. Tang, H. Yin, X. Liu, P. Jiang, and H. Liu, “Isolation, identification and cadmium adsorption of a high cadmium-resistant Paecilomyces lilacinus,” African J. Biotechnol., vol. 9, no. 39, pp. 6525–6533, 2010.

- E. Alori and O. Fawole, “Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Aluminium and Manganese by Two Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi,” J. Agric. Sci., vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 246–252, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Hassan, A. Pariatamby, I. C. Ossai, and F. S. Hamid, “Bioaugmentation assisted mycoremediation of heavy metal and/metalloid landfill contaminated soil using consortia of filamentous fungi,” Biochem. Eng. J., vol. 157, no. February, p. 107550, 2020. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2020.107550. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Joshi, A. Swarup, S. Maheshwari, R. Kumar, and N. Singh, “Bioremediation of Heavy Metals in Liquid Media Through Fungi Isolated from Contaminated Sources,” Indian J. Microbiol., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 482–487, 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. Sey and E. J. D. Belford, “Heavy Metals Tolerance Potential of Fungi Species Isolated from Gold Mine Tailings in Ghana,” J. Environ. Heal. Sustain. Dev., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1231–1242, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Chun, Y. J. Kim, Y. Cui, and K. H. Nam, “Ecological network analysis reveals distinctive microbial modules associated with heavy metal contamination of abandoned mine soils in Korea,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 289, no. January, p. 117851, 2021. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117851. [CrossRef]

- F. Liaquat et al., “Evaluation of metal tolerance of fungal strains isolated from contaminated mining soil of Nanjing, China,” Biology (Basel)., vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Zotti, S. Di Piazza, E. Roccotiello, G. Lucchetti, M. G. Mariotti, and P. Marescotti, “Microfungi in highly copper-contaminated soils from an abandoned Fe-Cu sulphide mine: Growth responses, tolerance and bioaccumulation,” Chemosphere, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 471–476, 2014. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.057. [CrossRef]

- O. G. Oladipo, O. O. Awotoye, A. Olayinka, C. C. Bezuidenhout, and M. S. Maboeta, “Heavy metal tolerance traits of filamentous fungi isolated from gold and gemstone mining sites,” Brazilian J. Microbiol., vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 29–37, 2018. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2017.06.003. [CrossRef]

- A. Singh and A. Roy, In Fungal communities for the remediation of environmental pollutants, A. N. Yada., vol. 1. Springer International Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

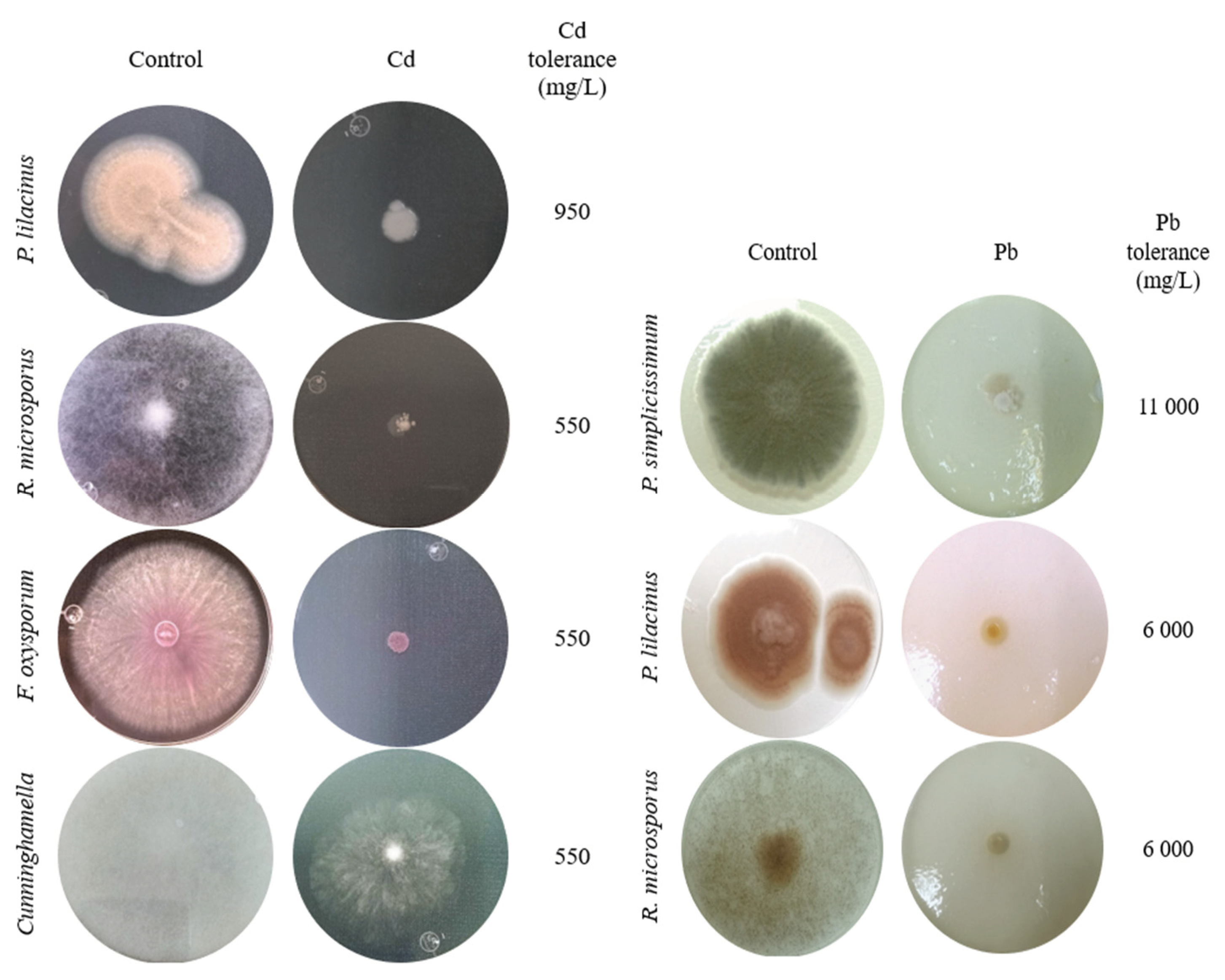

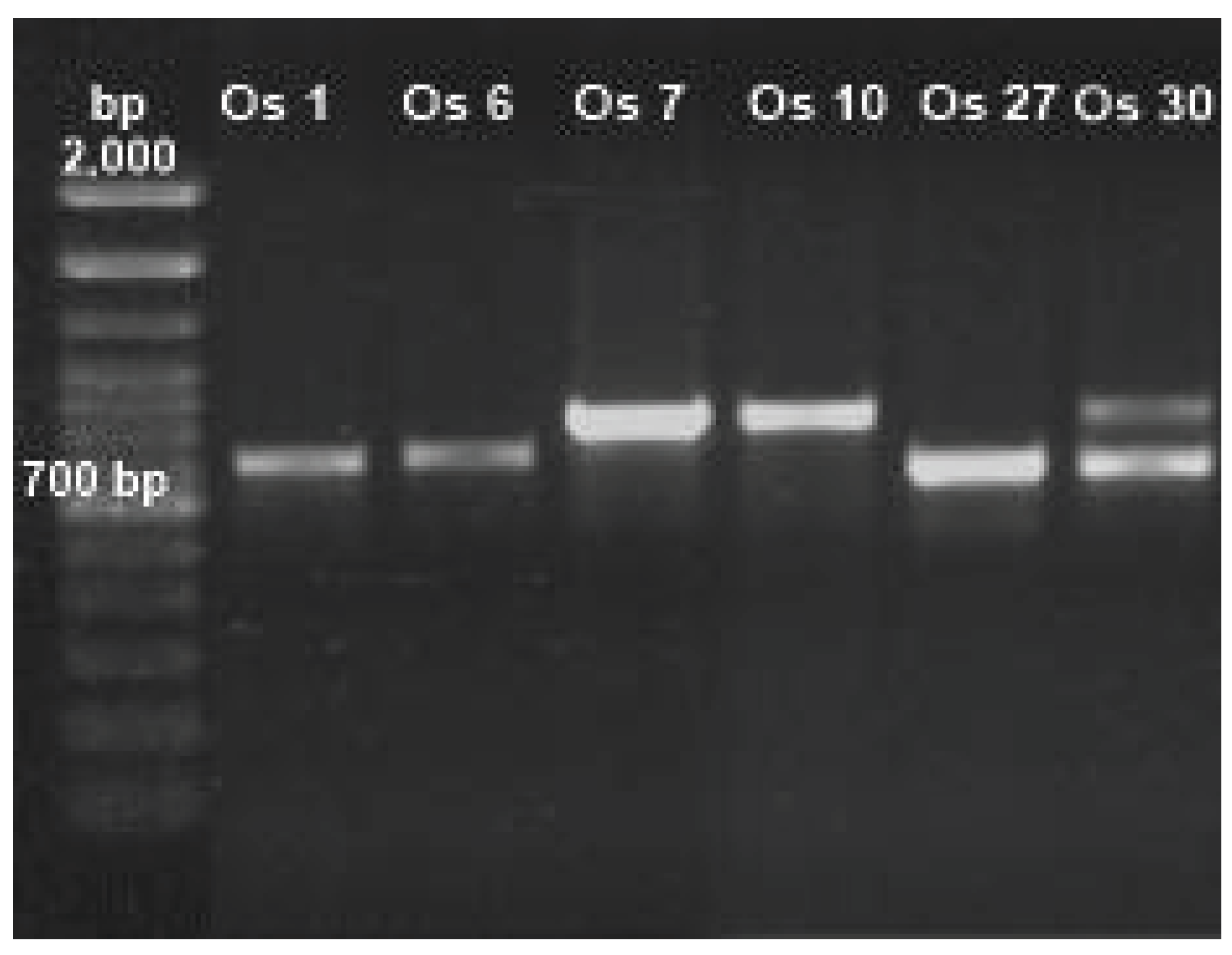

| Isolate ID | Morphological identification | Size (bp) | Molecular identification | Coincidence (%) | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Os 1 Os 6 Os 7 |

Penicillium sp. | 552 | P. simplicissimum | 99.4 | MW485753.1 |

| Paecilomyces sp. | 641 | P. lilacinus | 99.8 | MT453285.1 | |

| Rhizopus sp. | 664 | R. microsporus | 100 | MH473977.1 | |

|

Os 10 Os 27 |

Rhizopus sp. | 666 | R. microsporus | 100 | MH473977.1 |

| Fusarium sp. | 513 | F. oxysporum | 99.6 | KX655587.1 | |

|

Os 30 Os 1 |

Cuninghamella sp. | 715 | Cuninghamella sp. | 87.5 | OR096349.1 |

| Penicillium sp. | 552 | P. simplicissimum | 99.4 | MW485753.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).