1. Introduction

Melasma is a common acquired hyperpigmentation disorder, characterized by brownish spots on photoexposed areas such as the face, neck, shoulders, and upper chest [

1]. The condition is more prevalent in women of childbearing age, although men with intermediate skin phototypes may also be affected [

2]. The pathogenesis of melasma involves focal hyperactivity of epidermal melanocytes, which are primarily stimulated by ultraviolet (UV) radiation, leading to increased melanin production [

1].

Although the exact etiology of melasma is not fully understood, multiple factors are associated with its development. UV exposure remains the main triggering factor, and visible light also plays a significant role in worsening the condition [

1,

2,

3]. Genetic predisposition has been documented, suggesting hereditary susceptibility [

4]. Hormonal alterations, including pregnancy, oral contraceptives, and hormone therapies, are strongly linked to melasma onset [

1]. Other contributing factors include certain medications and endocrine disorders, such as polycystic ovary syndrome [

2].

Melasma treatment is often challenging, with limited therapeutic responses that may frustrate patients. Available options include depigmenting agents like hydroquinone, kojic acid, and tretinoin [

5]. Laser treatments and strict sun protection have shown promise, but combined approaches are often necessary for significant improvement [

6]. Due to the recurrent nature of this condition, melasma management remains a clinical challenge [

1].

Exosomes have emerged as a promising alternative for the treatment of various dermatological conditions, including melasma. These extracellular vesicles, primarily secreted by stem cells, are responsible for intercellular communication and mediate molecular information to the surrounding cellular environment [

7,

8]. ASCE-plus SRLV, a compound that contains exosomes derived from

Rosa damascena stem cells, along with hyaluronic acid, six minerals, nine growth factors, thirty amino acids, six peptides, four coenzymes, vitamins, and retinol, has been investigated for its therapeutic properties [

9].

Studies have shown that exosomes derived from

Rosa damascena stem cells (RSCEs) contain microRNAs (miRNAs) and peptides with remarkable anti-inflammatory properties, which are capable of inducing fibroblast proliferation, increasing collagen production, and reducing melanin accumulation in a dose-dependent manner [

10]. These characteristics indicate that exosomes have significant potential in modulating cellular processes involved in skin pigmentation, opening new perspectives for the treatment of conditions such as melasma.

However, the stratum corneum acts as a major barrier to the penetration of larger molecules, such as exosomes. According to the “500 Dalton rule,” a molecule must weigh less than 500 Da to cross this barrier. This raises concerns about the ability of exosomes, which are nanometric in size, to permeate the skin [

11]. Techniques like microneedling and laser microporation are used to increase skin permeability and facilitate exosome delivery.

One of the most used mechanisms for skin permeation is microneedling. It is a minimally invasive procedure widely employed in the treatment of melasma. On its own, it has shown efficacy in improving the clinical condition [

12]. The technique involves the application of microneedles with variable depths ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 mm, creating micro-injuries in the epidermis and dermis and triggering a controlled inflammatory process. This stimulus activates fibroblasts, inducing neocollagenesis and elastin production, which contributes to the renewal of the extracellular matrix and improvement in skin quality [

12,

13].

In addition to structural effects, microneedling has been shown to reduce epidermal hyperpigmentation and the presence of dermal melanophages, promoting the degradation of excess melanin accumulated in the dermis [

14]. Furthermore, the transdermal channels formed by the procedure increase skin permeability, allowing greater absorption of brightening agents such as tranexamic acid, kojic acid, and vitamin C, thereby enhancing their therapeutic effects in the treatment of melasma [

15].

Recent studies suggest that combining microneedling with topical agents or technologies like laser or intense pulsed light enhances outcomes, reducing recurrence and improving skin tone uniformity [

16]. The depth of needle penetration and frequency of sessions must be tailored to skin phenotype and pigmentation severity to prevent post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and maximize therapeutic benefits.

Although clinical studies on exosomes for skin disorders are still limited, their use in dermatology is increasing. Evaluating the efficacy of combining microneedling with exosomes versus microneedling alone is essential for determining the safety, benefits, and therapeutic potential of this approach in melasma treatment.

The objective on this article is to compare the efficacy of microneedling combined with the use of exosomes (ASCE-plus SRLV) versus microneedling alone in the treatment of melasma, evaluating clinical outcomes, tolerability, and safety.

2. Methodology

A randomized, double-blind, controlled pilot clinical trial was conducted with a convenience sample of female patients attending the dermatology outpatient clinic of a public hospital in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Twelve women aged 34 to 57 years, with Fitzpatrick skin types II–IV and clinically diagnosed melasma, were included regardless of prior depigmenting treatments or disease duration. Exclusion criteria included occupational or recreational sun exposure, concurrent pigmentary disorders, pregnancy, and lactation.

Participants were randomly assigned using sealed envelopes. Group 1 received microneedling followed by topical application of 1 mL of ASCE-plus SRLV, applied manually and left on the skin for 8 hours. Group 2 received microneedling followed by topical application of saline solution, following the same protocol.

All patients received topical anesthesia before the procedure, and skin asepsis was performed with aqueous chlorhexidine. Microneedling was performed using an electric device (Dermapen) set to a depth of 0.4 mm. Each participant underwent three sessions spaced 28 days apart. During the study period, patients were instructed to use broad-spectrum tinted sunscreen daily, discontinue topical acids, and avoid direct sun exposure.

Treatment efficacy was assessed before and after the three sessions using objective methods. 3D photographic records (Quantificare) documented pigmentation changes. Melasma severity was measured using MASI, and aesthetic improvement was rated using GAIS by two blinded independent dermatologists.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and Excel 365. All statistical tests were conducted with a 5% significance level (p ≤ 0.05). Only valid responses were included in the analysis. Results were presented in tables with absolute and relative frequencies. Numerical variables were described using measures of central tendency and dispersion. Associations between categorical variables were tested using Fisher’s Exact Test. Comparisons between independent groups used the Mann-Whitney test, while paired groups were compared using the Wilcoxon test. Intraobserver reliability of clinical and photographic assessments was measured using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

The project complies with Resolution No. 510, dated April 7, 2016, of the Brazilian National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde – CNS), which establishes ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa – CEP) of Hospital Otávio de Freitas under the Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Consideration (CAAE) No. 843841241.1.0000.5200, with approval opinion No. 7.362.879 issued on February 6, 2025 (Annex 1).

This study involves minimal risks inherent to the procedures performed. Topical anesthesia, although generally well tolerated, may cause mild and transient reactions such as skin irritation and temporary erythema, with systemic toxicity being extremely rare. Superficial microneedling may result in temporary discomfort, erythema, and edema, in addition to a small risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with higher phototypes. However, these reactions are self-limited and reversible. The topical application of exosomes following microneedling carries a theoretical risk of cutaneous sensitization or inflammatory response, but to date, no adverse effects have been reported in the literature regarding the use of ASCE-plus SRLV.

Confidentiality and privacy of information were ensured at all stages of the study, in accordance with current legislation, and will be maintained for five years under the responsibility of the principal investigator for future reference, in order to clarify any questions regarding the research conducted. After this period, the data will be securely destroyed.

3. Results

Twelve patients were included in the study. However, two did not adhere to photoprotection guidelines and were directly exposed to sunlight during the study period, leading to their exclusion based on the established exclusion criteria. Thus, ten patients completed the study. None of them experienced allergic reactions, hypersensitivity, or other adverse effects.

Population characteristics are listed in

Table 1. The mean age of participants was 45.1 ± 7.53 years, with a median of 45.0 years (39.5; 51.75) and a range of 34.0 to 57.0 years. The onset of the condition occurred at a mean age of 33.3 ± 5.01 years, with a median of 33.5 years (29.5; 36.75) and a range of 26.0 to 42.0 years. The disease duration averaged 11.8 ± 6.6 years, with a median of 10.5 years (6.0; 18.25) and ranged from 3.0 to 22.0 years. Regarding Fitzpatrick phototype, seven patients were classified as type III (70%), two as type IV (20%), and one as type V (10%).

Assessment of treatment response using the MASI index indicated a significant reduction in scores. For evaluator 1, the initial MASI score had a mean of 13.83 ± 3.59, a median of 13.55 (10.88; 16.88), and ranged from 8.0 to 19.5, decreasing to a mean of 9.24 ± 3.03, median of 9.60 (7.20; 10.80), and range of 4.80 to 14.90 post-treatment. For evaluator 2, the initial score was 12.03 ± 3.64, median of 12.15 (8.55; 14.93), ranging from 6.90 to 18.00, decreasing to a mean of 6.88 ± 2.90, median of 6.65 (4.50; 8.63), and values between 3.50 and 12.60 after the intervention. The absolute difference in MASI (Δ MASI) supported this improvement, with mean values of 4.59 ± 2.75 for evaluator 1 (median of 5.20; range 0.00 to 7.80) and 5.15 ± 2.62 for evaluator 2 (median of 4.60; range 1.00 to 8.40). Moreover, global improvement assessment using GAIS showed that 80.0% of patients were rated at level 2 by both evaluators, while the remaining 20.0% were rated at level 3, reinforcing the positive perception of the treatment’s clinical effects.

In

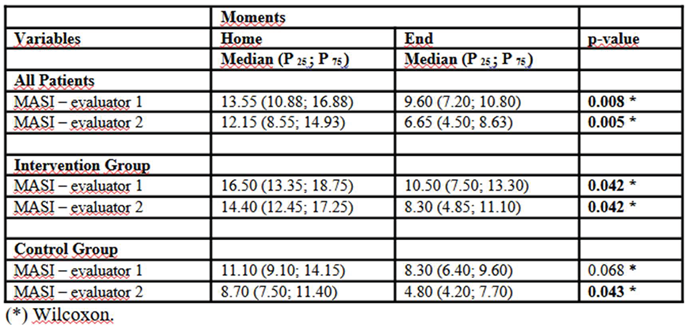

Table 2, the median initial MASI score assessed by the first evaluator was significantly higher in the Intervention group (16.50; P25–P75: 13.35–18.75) compared to the Control group (11.10; P25–P75: 9.10–14.15; p = 0.047). The same pattern was observed in the second evaluator’s assessment, with a higher initial MASI score in the Intervention group (14.40; P25–P75: 12.45–17.25) versus the Control group (8.70; P25–P75: 7.50–11.40; p = 0.016), suggesting that patients in the intervention group presented with a more severe clinical picture at baseline. However, there were no statistically significant differences in final scores for either evaluator (p = 0.093 for evaluator 1 and p = 0.293 for evaluator 2). The absolute difference in MASI (Δ MASI) also indicated a greater reduction in the Intervention group compared to the Control group, particularly in the second evaluator’s assessment (median of 8.20 in the Intervention group versus 3.90 in the Control group; p = 0.059), though without reaching statistical significance. Fitzpatrick phototype distribution was similar between groups, with no significant differences (p = 1.000), as were participant age (median of 45.00 years in both groups; p = 1.000) and disease duration (p = 1.000). The global improvement perception by GAIS indicated that all patients in the Intervention group were rated at level 2 by both evaluators, while in the Control group, 40% were rated at level 3 and 60% at level 2, with no statistically significant differences between groups (p = 0.444).

Table 3 shows that MASI score analysis over time revealed a significant reduction in clinical severity among the evaluated patients. Considering all participants, there was a notable decrease in MASI scores by both evaluators, with median reductions from 13.55 (P25–P75: 10.88–16.88) to 9.60 (P25–P75: 7.20–10.80; p = 0.008) and from 12.15 (P25–P75: 8.55–14.93) to 6.65 (P25–P75: 4.50–8.63; p = 0.005), respectively. When results were stratified by group, patients in the Intervention group showed significant improvement, with MASI score reductions for evaluator 1 from 16.50 (P25–P75: 13.35–18.75) to 10.50 (P25–P75: 7.50–13.30; p = 0.042), and for evaluator 2 from 14.40 (P25–P75: 12.45–17.25) to 8.30 (P25–P75: 4.85–11.10; p = 0.042). The Control group also showed clinical improvement, although to a lesser extent. The initial MASI recorded by evaluator 1 decreased from 11.10 (P25–P75: 9.10–14.15) to 8.30 (P25–P75: 6.40–9.60), though not statistically significant (p = 0.068). Evaluator 2’s assessment revealed a significant reduction from 8.70 (P25–P75: 7.50–11.40) to 4.80 (P25–P75: 4.20–7.70; p = 0.043). These findings suggest that although both groups showed improvement over time, the intervention may have had a greater impact in reducing the clinical severity of the condition.

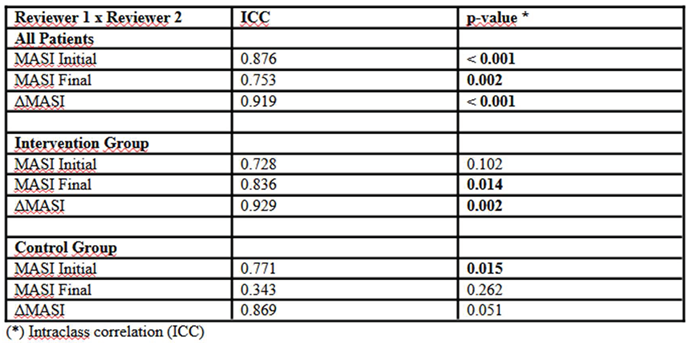

The analysis of inter-rater agreement, measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), revealed varying levels of reproducibility across the different evaluation stages (

Table 4). Considering all patients, agreement was high in the initial MASI assessment (ICC = 0.876; p < 0.001) and in the change in score over time (Δ MASI: ICC = 0.919; p < 0.001). However, agreement for the final MASI assessment was slightly lower (ICC = 0.753; p = 0.002), possibly indicating greater subjectivity in evaluating post-treatment clinical improvements. When analyzing groups separately, initial agreement in the intervention group did not reach statistical significance (ICC = 0.728; p = 0.102), suggesting more variability in evaluator interpretations at the study’s start. Nevertheless, final assessment reproducibility was significantly higher (ICC = 0.836; p = 0.014), indicating greater consistency in post-treatment observations. The change in MASI score over time maintained high reliability (Δ MASI: ICC = 0.929; p = 0.002). In the Control group, agreement was significant in the initial evaluation (ICC = 0.771; p = 0.015), but no significant correlation was observed in the final evaluation (ICC = 0.343; p = 0.262), indicating greater evaluator interpretation discrepancies after the follow-up period. However, the change in MASI score (Δ MASI) maintained good agreement (ICC = 0.869; p = 0.051), albeit without statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicated that both microneedling alone and its association with the use of exosomes were effective in reducing the severity of melasma, as measured by the MASI score. Both evaluators recorded a significant reduction in index values, reinforcing the effectiveness of the treatment. Improvement was more pronounced in the intervention group, with a MASI reduction from 16.50 to 10.50 according to the first evaluator (p=0.042) and from 14.40 to 8.30 according to the second evaluator (p=0.042), whereas the control group also showed improvement, but with lower magnitude and no statistical significance in some assessments. Clinical images (

Figure 1) illustrate the reduction in hyperpigmentation over time in the group that received exosome application, while the control group showed more modest improvement (

Figure 2).

The distribution of Fitzpatrick phototypes (70% type III, 20% type IV, and 10% type V) reflects a representative sample of individuals who often present therapeutic challenges due to a greater propensity for post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. This characteristic is relevant, as patients with higher phototypes tend to present variable responses to melasma treatments, which may influence the efficacy and safety of interventions [

1].

The overall perception of improvement assessed by the GAIS reinforces the benefits of the treatment, with 80% of participants classified at level 2, indicating significant improvement. In the intervention group, all patients were classified at this level, while in the control group, 40% were classified at level 3, suggesting a less pronounced response to standard treatment.

The reliability of the assessment was tested using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), demonstrating high agreement in the initial MASI evaluation (ICC = 0.876; p < 0.001) and in the variation of the score over time (ICC = 0.919; p < 0.001). However, agreement in the final evaluation was slightly lower (ICC = 0.753; p = 0.002), which may indicate greater subjectivity in the measurement of clinical improvement. In the intervention group, there was an improvement in inter-rater agreement in the final phase of the study, suggesting that the treatment response was more uniform and noticeable. In contrast, in the control group, greater discrepancy in the final evaluation may reflect subtle differences in clinical response, making measurement more subjective.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous literature demonstrating the efficacy of similar interventions in the management of melasma. Cassiano et al. [

14] investigated the effects of microneedling at a depth of 1.5 mm in 20 patients, demonstrating significant histopathological improvement after a single session. Similarly, Taher, El-Sayed, and Bessar [

17] compared microneedling at 1.5 mm with placebo on hemifaces of 17 patients and observed a statistically significant reduction in melasma lesions.

However, studies on the use of microneedling at shallower depths (≤ 0.5 mm) for the treatment of melasma are scarce, with most research focusing on this technique to enhance the permeation of topical agents. Farag et al. [

18], in a split-face study with 30 patients, used microneedling at 0.25–0.5 mm associated with 5% topical methimazole. The study found statistical significance only on the treated hemiface, while the control side showed no significant changes. In contrast, the findings of the present study indicate clinical improvement in both the intervention and control groups, suggesting that microneedling, even at shallower depths, may provide therapeutic benefits, possibly through additional mechanisms such as inflammatory modulation or tissue remodeling.

Research on the use of exosomes in the treatment of melasma is progressing, although still in its early stages, especially regarding exosomes derived from the stem of

Rosa damascena (RSCEs). In an uncontrolled interventional study conducted by Proietti et al. [

19], a significant reduction in the Modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI) was observed after five sessions of 1.5 mm microneedling combined with RSCE application. The results showed that 90% of participants experienced clinical improvement. Among patients with severe melasma, 40% shifted to mild classification and 60% to moderate; in turn, among patients with moderate melasma, 88.9% progressed to the mild classification. These findings support the results of the present study, which demonstrated significant improvement even using a lower microneedling depth and a reduced number of sessions. These data underscore the relevance of exploring innovative biological therapies, such as exosomes derived from stem cells, which show promising potential in melasma management by acting through mechanisms of skin regeneration and pigmentation modulation.

Despite the efficacy observed in the intervention, some limitations must be considered. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results, and the absence of statistical significance in some comparisons highlights the need for studies with larger samples for more robust analysis. Additionally, the follow-up period may have been insufficient to assess the long-term durability of the effects. Another factor to consider is the complexity of the formulation used, which contains several substances, making it difficult to identify the isolated impact of exosomes on the observed outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrated the efficacy of microneedling combined with the use of exosomes in reducing the severity of melasma, as evidenced by a significant decrease in the MASI score compared to the control group, which underwent microneedling alone. The overall perception of improvement, assessed using the GAIS scale, supports these findings, highlighting a high rate of positive response to the treatment. Furthermore, the high reliability of the evaluations, confirmed by the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), reinforces the robustness of the data, particularly in score variation over time analysis, ensuring greater accuracy in the interpretation of results.

Despite limitations inherent to sample size and follow-up period, the results suggest that the intervention may represent a promising approach in the management of the condition studied. Future studies with larger samples and extended follow-up are needed to validate these findings and investigate the durability of the observed benefits. In addition, combining this intervention with other therapeutic modalities and incorporating biomarkers may contribute to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved in treatment response. Thus, the present research provides a relevant foundation for further investigations and potential clinical applications of this therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dermatology outpatient clinic team and participating patients for their contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miot LD, Miot HA, Silva MG, Marques MEA (2009) Fisiopatologia do melasma. An Bras Dermatol 84(6): 623–635. [CrossRef]

- Handel AC, Miot LD, Miot HA (2014) Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case–control study. British Journal of Dermatology 171(3): 588–594. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Li Y, Wang Y (2022) Mechanisms of ultraviolet-induced melasma formation: A review. J Dermatol 49(12): 1201–1210. [CrossRef]

- Holmo NF, Ramos GB, Salomão H, Werneck RI, Mira MT, Miot LD (2018) Complex segregation analysis of facial melasma in Brazil: evidence for a genetic susceptibility with a dominant pattern of segregation. Arch Dermatol Res 310(10): 827–831. [CrossRef]

- McKesey J, Tovar-Garza A, Pandya AG (2020) Melasma Treatment: An Evidence-Based Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 21(2): 173–225. [CrossRef]

- Philipp-Dormston WG, Vila Echagüe A, Pérez Damonte SH, Riedel J, Filbry A, Warnke K, et al. (2023) Melasma: A Step-by-Step Approach Towards a Multimodal Combination Therapy. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 16: 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PRM, Andreu Z, Bedina Zavec A, Borràs FE, et al. (2015) Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles 4(1): 27066. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979354.

- Wu J, Wu S, Zhang L, Zhao X, Li Y, Yang QY, et al. (2022) Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: A New Method for Reversing Skin Aging. Tissue Eng Regen Med 19(5): 961–968. [CrossRef]

- Dal’Forno-Dini T, Birck MS, Rocha M, Bagatin E (2025) Explorando a realidade dos exossomos na Dermatologia. An Bras Dermatol 100(1): 121–130. [CrossRef]

- Won YJ, Lee E, Min SY, Cho BS (2023) Biological Function of Exosome-like Particles Isolated from Rose (Rosa Damascena) Stem Cell Culture Supernatant. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Bos JD, Meinardi MM (2000) The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs. Exp Dermatol 9(3): 165–169. [CrossRef]

- El Attar Y, Doghaim N, El Far N, El Hedody S, Hawwam SA (2022) Efficacy and Safety of Tranexamic Acid Versus Vitamin C After Microneedling in Treatment of Melasma: Clinical and Dermoscopic Study. J Cosmet Dermatol 21(7): 2817–2825. [CrossRef]

- Iriarte C, Awosika O, Rengifo-Pardo M, Ehrlich A (2017) Review of applications of microneedling in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 10: 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Cassiano DP, Espósito AC, Hassun KM, Lima EV, Bagatin E, Miot HA (2019) Early clinical and histological changes induced by microneedling in facial melasma: A pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 85(6): 638–641. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Su H, Xie J (2024) The efficacy and safety of microneedling with topical tranexamic acid for melasma treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol 23(1): 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Jiryis B, Toledano O, Avitan-Hersh E, Khamaysi Z (2024) Management of Melasma: Laser and Other Therapies—Review Study. J Clin Med 13(5):1468. [CrossRef]

- Taher NA, El-Sayed MM, Bessar HA (2021) Efficacy of skin needling device versus placebo in treatment of melasma. Egypt J Hosp Med 85(1): 2968–2972. https://ejhm.journals.ekb.eg/article_151682.html.

- Farag A, Hammam M, Alnaidany N, et al. (2021) Methimazole in the treatment of melasma: A clinical and dermoscopic study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 14(2): 14–20. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8211339/.

- Proietti I, Battilotti C, Svara F, Innocenzi C, Spagnoli A, Potenza C (2024) Efficacy and Tolerability of a Microneedling Device Plus Exosomes for Treating Melasma. Appl Sci 14(16): 7252. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).