Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Parkinson’s Disease – Epidemiology, Aetiology, Current Treatments and the Search for Disease Modification

Methodology

Neuropathophysiology of Parkinson’s Disease - What We Know

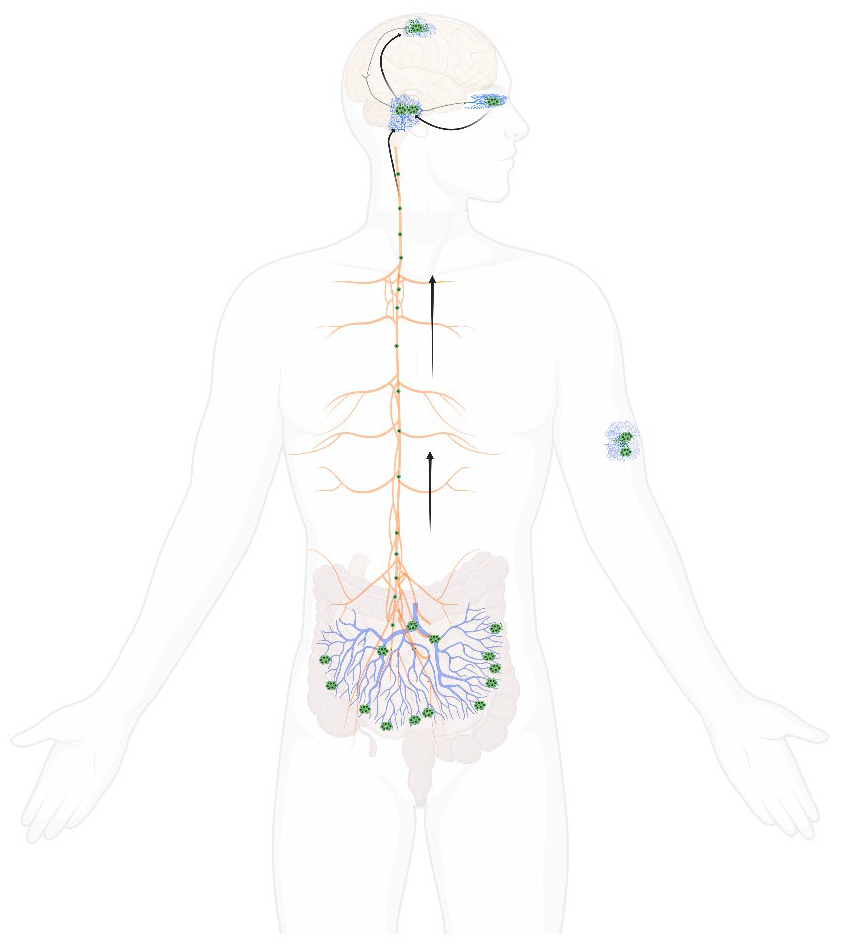

Alpha-Synuclein Aggregates, Known as Lewy Bodies, Are the Histopathological Hallmark of PD

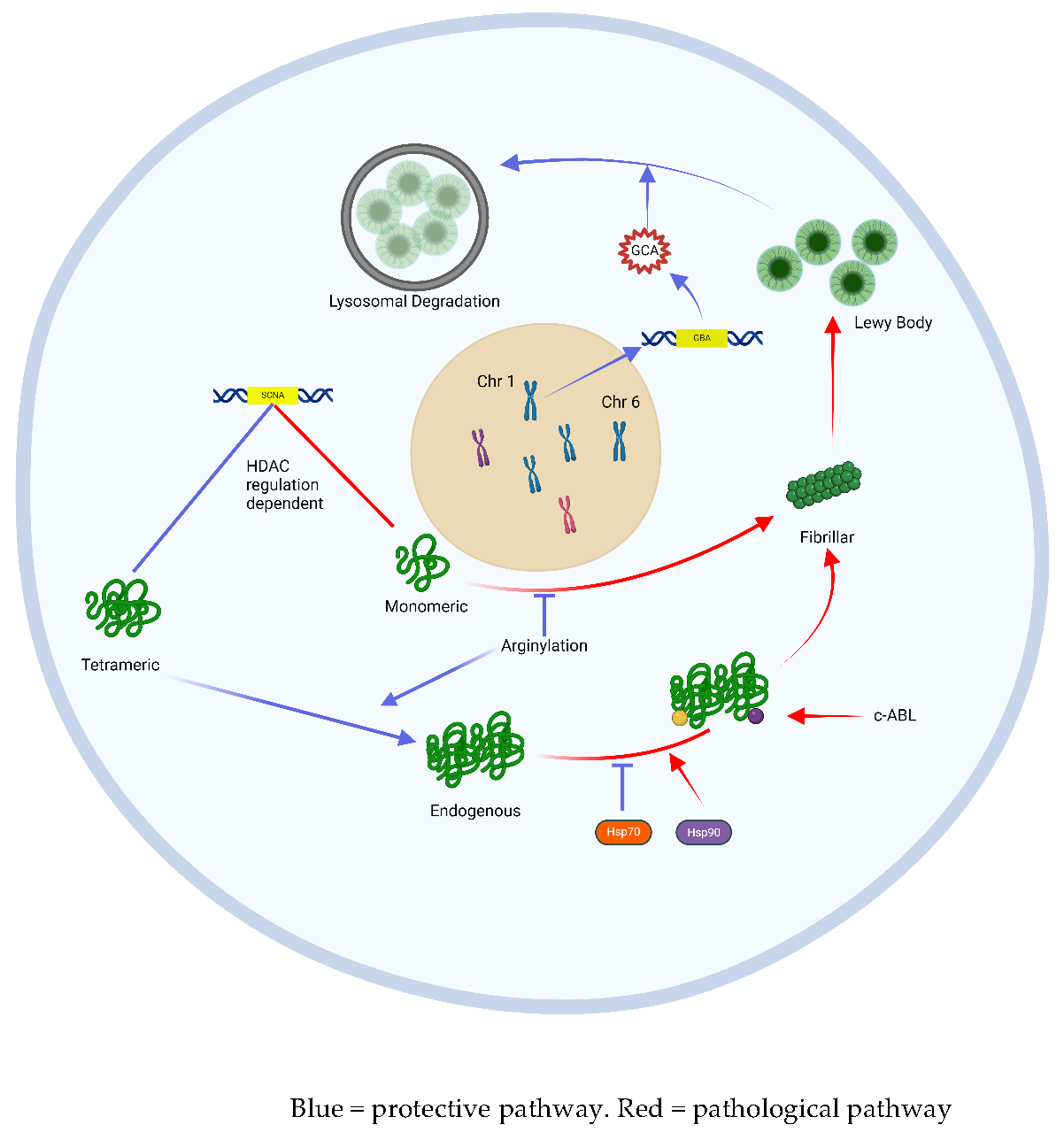

Alpha-Synuclein in the Neuron – Protective and Pathological Pathways

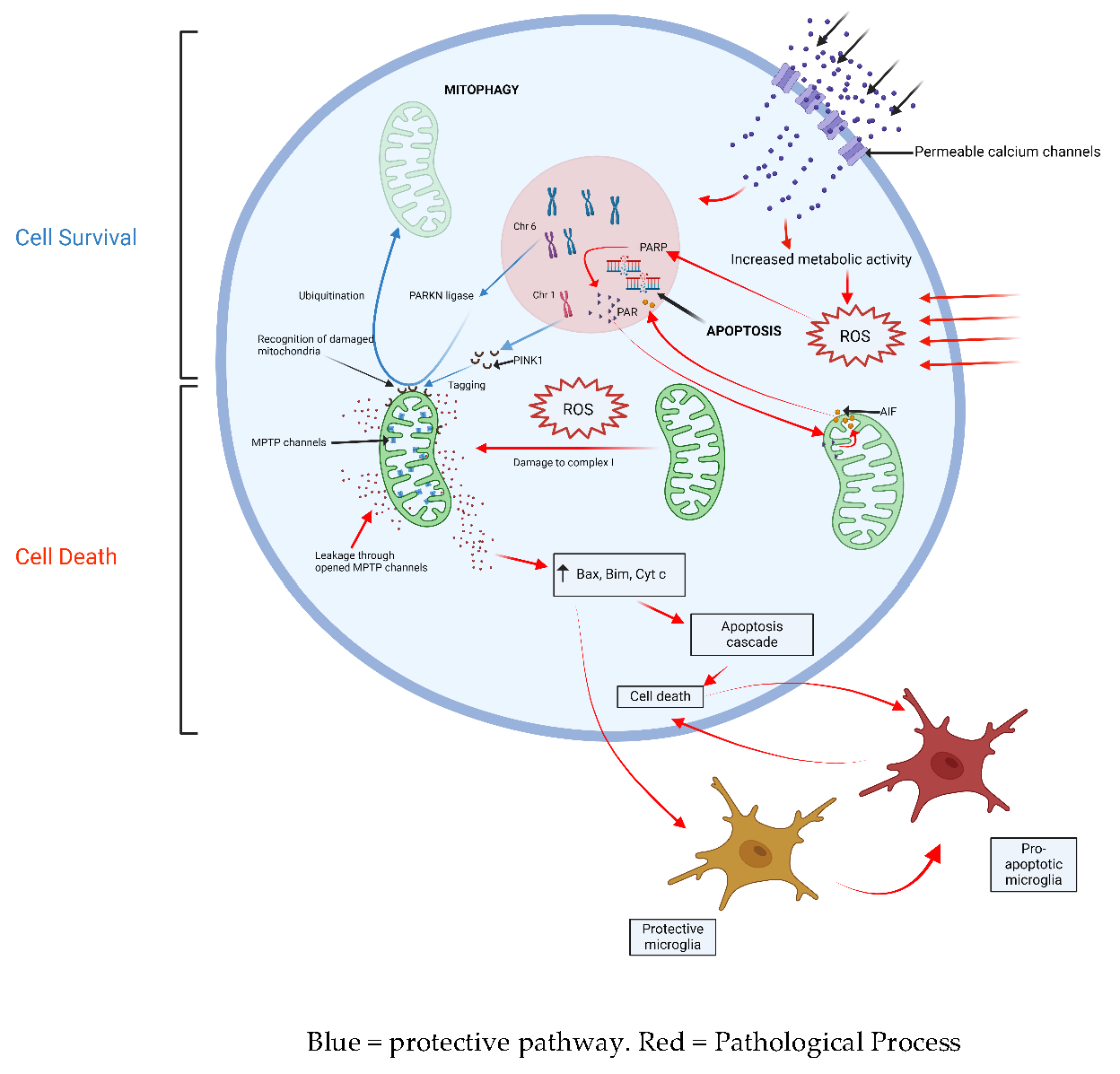

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induce Innate Immune Processes that Drive Cell Death in PD

Interactions Between Oxidative Stress, Mitochondria and Innate Immunity

The Vicious Cycle of Oxidative Stress and Alpha-Synuclein Deposition

Targets for Disease Modification

Prevention and Attenuation of Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation

Modification of Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neuroinflammation

Regeneration of Lost Neurons

Repurposing Old Drugs

| Agent/Intervention | Mechanism of action | Efficacy in preclinical models | Participant profile/human trial form | Status |

| alpha-synuclein | ||||

| Salbutamol (beta2AR agonist) | ?suppression of SCNA gene expression | Large Norwegian cohort of salbutamol users | Cohort data demonstrating 34% lifetime risk reduction | |

| Clenbuterol (beta2AR agonist) | ?suppression of SCNA gene expression | Protection of SNPc neurons in MPTP mouse models | ||

| siFTO (upstream SCNA gene regulator) | ?suppression of SCNA gene expression through upstream moodlation of FTO gene function | Neuroprotective in mouse models of PD | ||

| UCB0599 | Inhibition of aS misfolding and aggregation | Phase 1/1b trial | Good tolerability amongst 94 volunteers | |

| ABT888 | Inhibition of as misfiling and aggregation (?through inhibition of PARP-1) | Reduced deposition of fibrillar aS in mouse brains | ||

| Geldanamycin | Upregulation of HsP mediated proteosomal activity | Prevention of dopaminergic neuron degeneration in MPTP mouse models | ||

| NanoCA | Upregulation of tfEB mediated aS clearance | Protection against MPP+ induced neuron toxicity | ||

| GY4137 | Prevention of aS nitration | Reduced aS aggression in mouse models | ||

| Nilotinib | c-abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Reduced dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in mouse models | Phase 1: 6 month triall of 76 participants | No clinical benefit on UPDRS motor score Poor CSF bioavailability |

| Vodobatinib | Novel c-abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Phase 1 tolerability study | Good CSF bioavailability, good tolerability | |

| PDO1A | Active immunization against aS | Phase 1: 32 participants, mild IPD (within 4 years of diagnosis) | Reduced CSF aS concentration in human PD participants | |

| Prasinezumab | Passive immunotherapy | Phase 2: 316 participants, early stage IPD | Negative result. | |

| Cinpanemab | Passive immunotherapy | Phase 2: 357 participants with early stage IPD | Negative result | |

| Mitochondrial dysfunciton/oxidative stress | ||||

| Vitamin E | Termination of oxidative chain reactions | Cohort meta-analysis —> DATATOP study —> 800 participants, early IPD |

Reduced IPD incidence Modest benefit in UPDRS score over 12 week treatment period |

|

| IV + oral NAC (N-acetyl choline) | Antioxidant | Enhanced dopaminergic neuronal viability in 6-OHDA PD mouse model | Phase 1: 42 participants, mild IPD | Increased DAT binding in caudate and putamen |

| Intranasal glutathione | Antioxidant | Phase 2 | Negative trial | |

| Inosine | Increases urate concentration | Phase 1 —> Phase 2 —> 298 participants, 2 year treatment |

Increases CSF urate concentration, well tolerated Negative trial |

|

| Lipophilic metalloporphyrins | Novel scavenger antioxidant | Preserves ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons in mice models | ||

| Rapamycin | Reduced mitochondrial stress | Dopaminergic neuron protection in LRRK2 mutant mice | ||

| Immune modulation | ||||

| C-DIM12 | Microglial nuclear receptor-4A2 ligand | Neuroprotective in MPTP knockout mice | ||

| Dexamethasone liposome vector | Dexamethasone delivery to CD163+ macrophages | Neuroprotective in 6-OHDA mouse model | ||

| NLY01 | Modification of microglia activity | 36 week trial of 255 participants with early PD | Negative result | |

| Regeneration of lost dopaminergic neurons | ||||

| Stem cell therapies | Regeneration of lost neurons | Pending | Pending | |

| Intraputamenal injection of CDNF | Neurotrophic stimulation of puatmenal stem cells | Phase 1 trial | Good tolerability | |

| Repurposing of old drugs | ||||

| Isradipine | Calcium channel blocker ?reduced metabolic toxicity to dopaminergic neurons | Protective in mouse models | Phase 3 —> 336 participants, early stage IPD (<3yrs) | Negative result |

| SU4312 | Anti-cancer agent, ?MAO-B inhibition | Neuroprotective in MPTP mouse models | ||

| Exanatide | GLP-1 agonist | Cohort study —> Phase 2 clinical trial —> 62 participants, early PD |

Neuroprotective in 6-OHDA mouse model Negative trial |

|

| Fingolimod | S1P modulator AND aS modulator | Neuroprotective in 6-OHDA mouse model |

COVID-19: A Unique Window into the Pathogenesis of IPD?

Conclusions and ‘Where to from Here’

References

- Fearnley, J. M. and A. J. Lees (1991). "Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity." Brain 114 ( Pt 5): 2283-2301. [CrossRef]

- Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(10):565-81. [CrossRef]

- Hung AY, Schwarzschild MA. Approaches to Disease Modification for Parkinson's Disease: Clinical Trials and Lessons Learned. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(4):1393-405. [CrossRef]

- Grenn FP, Kim JJ, Makarious MB, Iwaki H, Illarionova A, Brolin K, et al. The Parkinson's Disease Genome-Wide Association Study Locus Browser. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(11):2056-67.

- Kim CY, Alcalay RN. Genetic Forms of Parkinson's Disease. Semin Neurol. 2017;37(2):135-46.

- Poewe W, Seppi K, Marini K, Mahlknecht P. New hopes for disease modification in Parkinson's Disease. Neuropharmacology. 2020;171:108085. [CrossRef]

- Jackson H, Anzures-Cabrera J, Simuni T, Postuma RB, Marek K, Pagano G. Identifying prodromal symptoms at high specificity for Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1232387. [CrossRef]

- Fengler S, Liepelt-Scarfone I, Brockmann K, Schaffer E, Berg D, Kalbe E. Cognitive changes in prodromal Parkinson's disease: A review. Mov Disord. 2017;32(12):1655-66. [CrossRef]

- Fang C, Lv L, Mao S, Dong H, Liu B. Cognition Deficits in Parkinson's Disease: Mechanisms and Treatment. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;2020:2076942. [CrossRef]

- Poewe W, Antonini A, Zijlmans JC, Burkhard PR, Vingerhoets F. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: an old drug still going strong. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:229-38. [CrossRef]

- Kordower JH, Burke RE. Disease Modification for Parkinson's Disease: Axonal Regeneration and Trophic Factors. Mov Disord. 2018;33(5):678-83. [CrossRef]

- Kalia LV, Kalia SK, Lang AE. Disease-modifying strategies for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(11):1442-50.

- Engelhardt E, Gomes MDM. Lewy and his inclusion bodies: Discovery and rejection. Dement Neuropsychol. 2017;11(2):198-201. [CrossRef]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197-211. [CrossRef]

- Hilker R, Schweitzer K, Coburger S, Ghaemi M, Weisenbach S, Jacobs AH, et al. Nonlinear progression of Parkinson disease as determined by serial positron emission tomographic imaging of striatal fluorodopa F 18 activity. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(3):378-82. [CrossRef]

- Athauda D, Foltynie T. Challenges in detecting disease modification in Parkinson's disease clinical trials. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;32:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Burre J, Sharma M, Sudhof TC. Cell Biology and Pathophysiology of alpha-Synuclein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(3).

- Melki, R. Alpha-synuclein and the prion hypothesis in Parkinson's disease. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2018;174(9):644-52. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi M, Collins LM, Sullivan AM, O'Keeffe GW. The class II histone deacetylases as therapeutic targets for Parkinson's disease. Neuronal Signal. 2020;4(2):Ns20200001. [CrossRef]

- Thomas EA, D'Mello SR. Complex neuroprotective and neurotoxic effects of histone deacetylases. J Neurochem. 2018;145(2):96-110. [CrossRef]

- Park G, Tan J, Garcia G, Kang Y, Salvesen G, Zhang Z. Regulation of Histone Acetylation by Autophagy in Parkinson Disease. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(7):3531-40. [CrossRef]

- Friesen EL, De Snoo ML, Rajendran L, Kalia LV, Kalia SK. Chaperone-Based Therapies for Disease Modification in Parkinson's Disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2017;2017:5015307. [CrossRef]

- Tao J, Berthet A, Citron YR, Tsiolaki PL, Stanley R, Gestwicki JE, et al. Hsp70 chaperone blocks alpha-synuclein oligomer formation via a novel engagement mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100613. [CrossRef]

- Riboldi GM, Di Fonzo AB. GBA, Gaucher Disease, and Parkinson's Disease: From Genetic to Clinic to New Therapeutic Approaches. Cells. 2019;8(4).

- Gan-Or Z, Bar-Shira A, Gurevich T, Giladi N, Orr-Urtreger A. Homozygosity for the MTX1 c.184T>A (p.S63T) alteration modifies the age of onset in GBA-associated Parkinson's disease. Neurogenetics. 2011;12(4):325-32. [CrossRef]

- Glajch KE, Moors TE, Chen Y, et al. Wild-type GBA1 increases the alpha-synuclein tetramer-monomer ratio, reduces lipid-rich aggregates, and attenuates motor and cognitive deficits in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(31).

- Pan B, Kamo N, Shimogawa M, Huang Y, Kashina A, Rhoades E, et al. Effects of Glutamate Arginylation on alpha-Synuclein: Studying an Unusual Post-Translational Modification through Semisynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(52):21786-98. [CrossRef]

- Mahul-Mellier AL, Fauvet B, Gysbers A, Dikiy I, Oueslati A, Georgeon S, et al. c-Abl phosphorylates alpha-synuclein and regulates its degradation: implication for alpha-synuclein clearance and contribution to the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(11):2858-79.

- Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29739-52. [CrossRef]

- Arawaka S, Sato H, Sasaki A, et al. Mechanisms underlying extensive Ser129-phosphorylation in alpha-synuclein aggregates. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):48. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem SS, Majbour NK, Vaikath NN, et al. α-Synuclein phosphorylation at serine 129 occurs after initial protein deposition and inhibits seeded fibril formation and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(15):e2109617119. [CrossRef]

- Irwin DJ, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Parkinson's disease dementia: convergence of alpha-synuclein, tau and amyloid-beta pathologies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(9):626-36.

- van der Gaag BL, Deshayes NAC, Breve JJP, Bol J, Jonker AJ, Hoozemans JJM, et al. Distinct tau and alpha-synuclein molecular signatures in Alzheimer's disease with and without Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2024;147(1):14.

- Skaper SD, Facci L, Zusso M, Giusti P. An Inflammation-Centric View of Neurological Disease: Beyond the Neuron. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:72. [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund G, Dadar M, Anderson G, Chirumbolo S, Maes M. Preventive treatments to slow substantia nigra damage and Parkinson's disease progression: A critical perspective review. Pharmacol Res. 2020;161:105065. [CrossRef]

- Park HA, Ellis AC. Dietary Antioxidants and Parkinson's Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(7). [CrossRef]

- Hastings L, Sokratian A, Apicco DJ, Stanhope CM, Smith L, Hirst WD, et al. Evaluation of ABT-888 in the amelioration of alpha-synuclein fibril-induced neurodegeneration. Brain Commun. 2022;4(2):fcac042. [CrossRef]

- Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2015;85(2):257-73.

- Wallings R, Manzoni C, Bandopadhyay R. Cellular processes associated with LRRK2 function and dysfunction. FEBS J. 2015;282(15):2806-26. [CrossRef]

- Le W, Wu J, Tang Y. Protective Microglia and Their Regulation in Parkinson's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:89. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds A, Laurie C, Mosley RL, Gendelman HE. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:297-325.

- Schwab AD, Thurston MJ, Machhi J, Olson KE, Namminga KL, Gendelman HE, et al. Immunotherapy for Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;137:104760.

- Grillo P, Sancesario GM, Bovenzi R, Zenuni H, Bissacco J, Mascioli D, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte count reflect alterations in central neurodegeneration-associated proteins and clinical severity in Parkinson Disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023;112:105480. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Zhao Y, Zhu G. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate in the development and progression of Parkinson's disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1288437. [CrossRef]

- Schwedhelm E, Englisch C, Niemann L, Lezius S, von Lucadou M, Marmann K, et al. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate, Motor Severity, and Progression in Parkinson's Disease (MARK-PD). Mov Disord. 2021;36(9):2178-82.

- Barrett PJ, Timothy Greenamyre J. Post-translational modification of alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2015;1628(Pt B):247-53.

- Pezzella A, d'Ischia M, Napolitano A, Misuraca G, Prota G. Iron-mediated generation of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine quinone by reaction of fatty acid hydroperoxides with dopamine: a possible contributory mechanism for neuronal degeneration in Parkinson's disease. J Med Chem. 1997;40(14):2211-6. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa JH, Santos AC, Tumas V, Liu M, Zheng W, Haacke EM, et al. Quantifying brain iron deposition in patients with Parkinson's disease using quantitative susceptibility mapping, R2 and R2. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33(5):559-65. [CrossRef]

- De Franceschi G, Fecchio C, Sharon R, Schapira AHV, Proukakis C, Bellotti V, et al. alpha-Synuclein structural features inhibit harmful polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation, suggesting roles in neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(17):6927-37.

- Abdelmotilib H, West AB. Breathing new life into an old target: pulmonary disease drugs for Parkinson's disease therapy. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Mittal S, Bjørnevik K et al. β2-Adrenoreceptor is a regulator of the α-synuclein gene driving risk of Parkinson's disease. Science. 2017;357(6354):891-8.

- Hopfner F, Höglinger GU et al. β-adrenoreceptors and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):247-54. [CrossRef]

- Geng Y, Long X et al. FTO-targeted siRNA delivery by MSC-derived exosomes synergistically alleviates dopaminergic neuronal death in Parkinson's disease via m6A-dependent regulation of ATM mRNA. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):652.

- den Heijer JM, Kruithof AC et al. A Phase 1B Trial in GBA1-Associated Parkinson's Disease of BIA-28-6156, a Glucocerebrosidase Activator. Mov Disord. 2023;38(7):1197-208.

- Wang Q, Luo Y, Ray Chaudhuri K, Reynolds R, Tan EK, Pettersson S. The role of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson's disease: mechanistic insights and therapeutic options. Brain. 2021;144(9):2571-93. [CrossRef]

- Sun MF, Zhu YL, Zhou ZL et al. Neuroprotective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease mice: Gut microbiota, glial reaction and TLR4/TNF-α signaling pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;70:48-60.

- Smit JW, Basile P, Prato MK et al. Phase 1/1b Studies of UCB0599, an Oral Inhibitor of α-Synuclein Misfolding, Including a Randomized Study in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2022;37(10):2045-56.

- Török N, Majláth Z, Szalárdy L, Vécsei L. Investigational α-synuclein aggregation inhibitors: hope for Parkinson's disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(11):1281-94. [CrossRef]

- Shen HY, He JC, Wang Y et al. Geldanamycin induces heat shock protein 70 and protects against MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(48):39962-9. [CrossRef]

- Sardoiwala MN, Karmakar S, Choudhury SR. Chitosan nanocarrier for FTY720 enhanced delivery retards Parkinson's disease via PP2A-EzH2 signaling in vitro and ex vivo. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;254:117435. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Liu C, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu K, Song JX, et al. A Self-Assembled alpha-Synuclein Nanoscavenger for Parkinson's Disease. ACS Nano. 2020;14(2):1533-49.

- Finkelstein DI, Billings JL, Adlard PA et al. The novel compound PBT434 prevents iron mediated neurodegeneration and alpha-synuclein toxicity in multiple models of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Devos D, Labreuche J, Rascol O et al. Trial of Deferiprone in Parkinson's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2045-55. [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Yuan Y, Sheng Y et al. GYY4137, an H(2)S Slow-Releasing Donor, Prevents Nitrative Stress and alpha-Synuclein Nitration in an MPTP Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:741.

- Pagan F, Hebron M, Valadez EH et al. Nilotinib Effects in Parkinson's disease and Dementia with Lewy bodies. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(3):503-17. [CrossRef]

- Pagan FL, Hebron ML, Wilmarth B et al. Nilotinib Effects on Safety, Tolerability, and Potential Biomarkers in Parkinson Disease: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(3):309-17.

- Werner, M.H. , Olanow, C.W., 2022. Parkinson's Disease Modification Through Abl Kinase Inhibition: An Opportunity. Movement Disorders 37, 6–15. [CrossRef]

- Walsh RR, Damle NK, Mandhane S et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of vodobatinib, a neuroprotective c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023;108:105281. [CrossRef]

- Volc D, Poewe W, Kutzelnigg A et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the alpha-synuclein active immunotherapeutic PD01A in patients with Parkinson's disease: a randomised, single-blinded, phase 1 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(7):591-600.

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Mante M et al. Passive immunization reduces behavioral and neuropathological deficits in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of Lewy body disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19338. [CrossRef]

- Jankovic J, Goodman I, Safirstein B et al. Safety and Tolerability of Multiple Ascending Doses of PRX002/RG7935, an Anti-alpha-Synuclein Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(10):1206-14.

- Pagano G, Boess FG, Taylor KI et al. A Phase II Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Prasinezumab in Early Parkinson's Disease (PASADENA): Rationale, Design, and Baseline Data. Front Neurol. 2021;12:705407. [CrossRef]

- Pagano G, Taylor KI, Anzures-Cabrera J, Marchesi M, Simuni T, Marek K, et al. Trial of Prasinezumab in Early-Stage Parkinson's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(5):421-32. [CrossRef]

- Lang AE, Siderowf AD, Macklin EA et al. Trial of Cinpanemab in Early Parkinson's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(5):408-20. [CrossRef]

- Park HA, Ellis AC. Dietary Antioxidants and Parkinson's Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(7). [CrossRef]

- Etminan M, Gill SS, Samii A. Intake of vitamin E, vitamin C, and carotenoids and the risk of Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(6):362-5.

- Parkinson Study, G. Effects of tocopherol and deprenyl on the progression of disability in early Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(3):176-83.

- Taghizadeh M, Tamtaji OR, Dadgostar E et al. The effects of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E co-supplementation on clinical and metabolic status in patients with Parkinson's disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurochem Int. 2017;108:183-9. [CrossRef]

- Tardiolo G, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. Overview on the Effects of N-Acetylcysteine in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules. 2018;23(12). [CrossRef]

- Virel A, Johansson J, Axelsson J et al. N-acetylcysteine decreases dopamine transporter availability in the non-lesioned striatum of the 6-OHDA hemiparkinsonian rat. Neurosci Lett. 2022;770:136420. [CrossRef]

- Monti DA, Zabrecky G, Kremens D et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine Is Associated With Dopaminergic Improvement in Parkinson's Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(4):884-90. [CrossRef]

- Mischley LK, Lau RC, Shankland EG et al. Phase IIb Study of Intranasal Glutathione in Parkinson's Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(2):289-99. [CrossRef]

- Crotty GF, Schwarzschild MA. Chasing Protection in Parkinson's Disease: Does Exercise Reduce Risk and Progression? Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:186.

- Investigators TPSGS-P. Effect of Urate-Elevating Inosine on Early Parkinson Disease Progression: The SURE-PD3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(10):926-39.

- Zhang C, Zhao M, Wang B et al. The Nrf2-NLRP3-caspase-1 axis mediates the neuroprotective effects of Celastrol in Parkinson's disease. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102134. [CrossRef]

- Liang LP, Fulton R, Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Pearson-Smith J, Day BJ, Patel M. Optimization of Lipophilic Metalloporphyrins Modifies Disease Outcomes in a Rat Model of Parkinsonism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2021;377(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Cooper O, Seo H, Andrabi S et al. Pharmacological rescue of mitochondrial deficits in iPSC-derived neural cells from patients with familial Parkinson's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(141):141ra90. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Zhi F, Mao J et al. delta-opioid receptor activation protects against Parkinson's disease-related mitochondrial dysfunction by enhancing PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(24):25035-59.

- Ham S, Lee YI, Jo M et al. Hydrocortisone-induced parkin prevents dopaminergic cell death via CREB pathway in Parkinson's disease model. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):525.

- Chen Y, Shen J, Ke K, Gu X. Clinical potential and current progress of mesenchymal stem cells for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(5):1051-61. [CrossRef]

- Cooray R, Gupta V, Suphioglu C. Current Aspects of the Endocannabinoid System and Targeted THC and CBD Phytocannabinoids as Potential Therapeutics for Parkinson's and Alzheimer's Diseases: a Review. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57(11):4878-90. [CrossRef]

- Hammond SL, Popichak KA, Li X et al. The Nurr1 Ligand,1,1-bis(3'-Indolyl)-1-(p-Chlorophenyl)Methane, Modulates Glial Reactivity and Is Neuroprotective in MPTP-Induced Parkinsonism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;365(3):636-51. [CrossRef]

- Tentillier N, Etzerodt A, Olesen MN et al. Anti-Inflammatory Modulation of Microglia via CD163-Targeted Glucocorticoids Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in the 6-OHDA Parkinson's Disease Model. J Neurosci. 2016;36(36):9375-90. [CrossRef]

- Lecca D, Nevin DK, Mulas G et al. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of a novel non-thiazolidinedione PPARγ agonist in vitro and in MPTP-treated mice. Neuroscience. 2015;302:23-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang YD, Bao XQ, Xu S et al. A Novel Parkinson's Disease Drug Candidate with Potent Anti-neuroinflammatory Effects through the Src Signaling Pathway. J Med Chem. 2016;59(19):9062-79. [CrossRef]

- Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD et al. Parkinsonian signs and substantia nigra neuron density in decendents elders without PD. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(4):532-9. [CrossRef]

- Kirkeby A, Parmar M, Barker RA. Strategies for bringing stem cell-derived dopamine neurons to the clinic: A European approach (STEM-PD). Prog Brain Res. 2017;230:165-90.

- Unnisa A, Dua K, Kamal MA. Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Multitarget Disease- Modifying Therapy for Parkinson's Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023;21(4):988-1000. [CrossRef]

- Song JJ, Oh SM, Kwon OC et al. Cografting astrocytes improves cell therapeutic outcomes in a Parkinson's disease model. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(1):463-82. [CrossRef]

- Marsili L, Sharma J, Outeiro TF et al. Stem Cell Therapies in Movement Disorders: Lessons from Clinical Trials. Biomedicines. 2023;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Stoddard-Bennett T, Pera RR. Stem cell therapy for Parkinson's disease: safety and modeling. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15(1):36-40. [CrossRef]

- Virachit S, Mathews KJ, Cottam V et al. Levels of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor are decreased, but fibroblast growth factor 2 and cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor are increased in the hippocampus in Parkinson's disease. Brain Pathol. 2019;29(6):813-25.

- Kirik D, Cederfjäll E, Halliday G et al. Gene therapy for Parkinson's disease: Disease modification by GDNF family of ligands. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;97(Pt B):179-88. [CrossRef]

- Huttunen HJ, Booms S, Sjogren M et al. Intraputamenal Cerebral Dopamine Neurotrophic Factor in Parkinson's Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Phase 1 Trial. Mov Disord. 2023;38(7):1209-22. [CrossRef]

- Francardo V, Geva M, Bez F et al. Pridopidine Induces Functional Neurorestoration Via the Sigma-1 Receptor in a Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16(2):465-79. [CrossRef]

- Fischer DL, Sortwell CE. BDNF provides many routes toward STN DBS-mediated disease modification. Mov Disord. 2019;34(1):22-34. [CrossRef]

- Hauser RA, Li R, Pérez A et al. Longer Duration of MAO-B Inhibitor Exposure is Associated with Less Clinical Decline in Parkinson's Disease: An Analysis of NET-PD LS1. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(1):117-27. [CrossRef]

- 1Guo B, Hu S, Zheng C, Wang H, Luo F, Li H, et al. Substantial protection against MPTP-associated Parkinson's neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo by anti-cancer agent SU4312 via activation of MEF2D and inhibition of MAO-B. Neuropharmacology. 2017;126:12-24. [CrossRef]

- Mullapudi A, Gudala K, Boya CS et al. Risk of Parkinson's Disease in the Users of Antihypertensive Agents: An Evidence from the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J Neurodegener Dis. 2016;2016:5780809. [CrossRef]

- Isradipine Versus Placebo in Early Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):591-8.

- Dietiker C, Kim S, Zhang Y et al. Characterization of Vitamin B12 Supplementation and Correlation with Clinical Outcomes in a Large Longitudinal Study of Early Parkinson's Disease. J Mov Disord. 2019;12(2):91-6. [CrossRef]

- Athauda D, Foltynie T. Insulin resistance and Parkinson's disease: A new target for disease modification? Prog Neurobiol. 2016;145-146:98-120.

- Athauda D, Wyse R, Brundin P et al. Is Exenatide a Treatment for Parkinson's Disease? J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7(3):451-8.

- Bu LL, Liu YQ, Shen Y et al. Neuroprotection of Exendin-4 by Enhanced Autophagy in a Parkinsonian Rat Model of α-Synucleinopathy. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18(2):962-78. [CrossRef]

- McGarry A, Rosanbalm S, Leinonen M et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt M, Dehay B, Bezard E et al. Harnessing the trophic and modulatory potential of statins in a dopaminergic cell line. Synapse. 2016;70(3):71-86. [CrossRef]

- Zhao P, Yang X, Yang L et al. Neuroprotective effects of fingolimod in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. FASEB J. 2017;31(1):172-9. [CrossRef]

- Roy D, Ghosh R, Dubey S et al. Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48(1):9-24. [CrossRef]

- Sulzer D, Antonini A, Leta V et al. COVID-19 and possible links with Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism: from bench to bedside. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2020;6:18. [CrossRef]

- Brundin P, Nath A, Beckham JD. Is COVID-19 a Perfect Storm for Parkinson's Disease? Trends Neurosci. 2020;43(12):931-3.

- Jang H, Boltz D, Sturm-Ramirez K et al. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus can enter the central nervous system and induce neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(33):14063-8. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman LA, Vilensky JA. Encephalitis lethargica: 100 years after the epidemic. Brain. 2017;140(8):2246-51. [CrossRef]

- Victorino DB, Guimarães-Marques M, Nejm M, Scorza FA et al. COVID-19 and Parkinson's Disease: Are We Dealing with Short-term Impacts or Something Worse? J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(3):899-902.

- Sadasivan S, Zanin M, O'Brien K et al. Induction of microglia activation after infection with the non-neurotropic A/CA/04/2009 H1N1 influenza virus. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124047.

- Jellinger, KA. Absence of alpha-synuclein pathology in postencephalitic parkinsonism. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(3):371-9. [CrossRef]

- Pavel A, Murray DK, Stoessl AJ. COVID-19 and selective vulnerability to Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):719. [CrossRef]

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Dubeau P et al. Human Coronaviruses and Other Respiratory Viruses: Underestimated Opportunistic Pathogens of the Central Nervous System? Viruses. 2019;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry ZL, Klenja D, Janjua N et al. COVID-19 and Parkinson's Disease: Shared Inflammatory Pathways Under Oxidative Stress. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11). [CrossRef]

- Fairfoul G, McGuire LI, Pal S, Ironside JW, Neumann J, Christie S, et al. Alpha-synuclein RT-QuIC in the CSF of patients with alpha-synucleinopathies. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(10):812-8.

- Okuzumi A, Hatano T, Matsumoto G et al. Propagative α-synuclein seeds as serum biomarkers for synucleinopathies. Nat Med. 2023;29(6):1448-55. [CrossRef]

- Iranzo A, Mammana A, Munoz-Lopetegi A et al. Misfolded alpha-Synuclein Assessment in the Skin and CSF by RT-QuIC in Isolated REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Neurology. 2023;100(18):e1944-e54. [CrossRef]

- Vijiaratnam N, Simuni T, Bandmann O et al. Progress towards therapies for disease modification in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(7):559-72. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Robles C, Bartlett M, Burnell, C.S. et al. Embedding Patient Input in Outcome Measures for Long-Term Disease-Modifying Parkinson Disease Trials. Mov Disord. 2024;39(2):433-8. [CrossRef]

- Lenka A, Jankovic J. How should future clinical trials be designed in the search for disease-modifying therapies for Parkinson's disease? Expert Rev Neurother. 2023;23(2):107-22.

- Ko WKD, Bezard E. Experimental animal models of Parkinson's disease: A transition from assessing symptomatology to alpha-synuclein targeted disease modification. Exp Neurol. 2017;298(Pt B):172-9. [CrossRef]

- Gao L, Tang H, Nie K et al. Cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein as a biomarker for Parkinson's disease diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125(9):645-54. [CrossRef]

- McGhee DJ, Ritchie CW, Zajicek JP et al. A review of clinical trial designs used to detect a disease-modifying effect of drug therapy in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:92. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).