Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Nicotine and Tobacco Smoking

2.2. Cancer Development and the Consequences of Smoking

2.3. Antioxidants

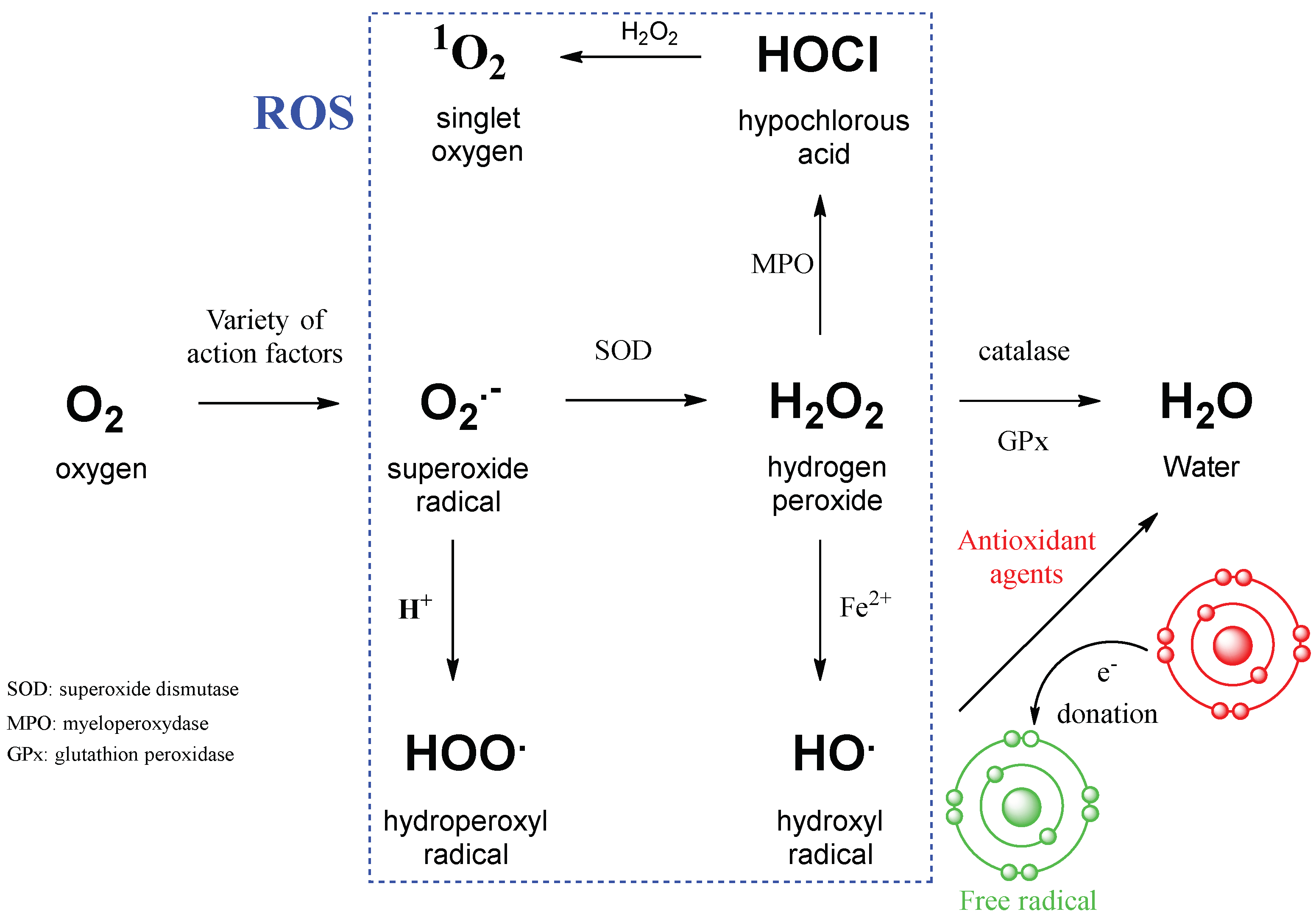

2.4. ROS in Cancer Development and Progression

2.5. On the Way to Quitting Smoking

3. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malarkey D.E., Hoenerhoff M., Maronpot R. R. Carcinogenesis: mechanisms and manifestations. In: Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, Third Edition, 2013, 107–146.

- Gupta P. C. The public health impact of tobacco. Current Science, 81, 5, 2001.

- Caturegli G., Zhu X., Palis B., Mullet T.M, Resio B.J. et al. Smoking status of the US cancer population and a new perspective from National cancer database. JAMA Oncol., 2025, 10.1001/jamaoncol.2025.0247.

- Szent-Gyorgyi A. Introduction to a sub-molecular biology. Academic Press, New York, NY, USA, London, UK. 1960.

- Schieber M., Chandel N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2014, 24, 453–R462. [CrossRef]

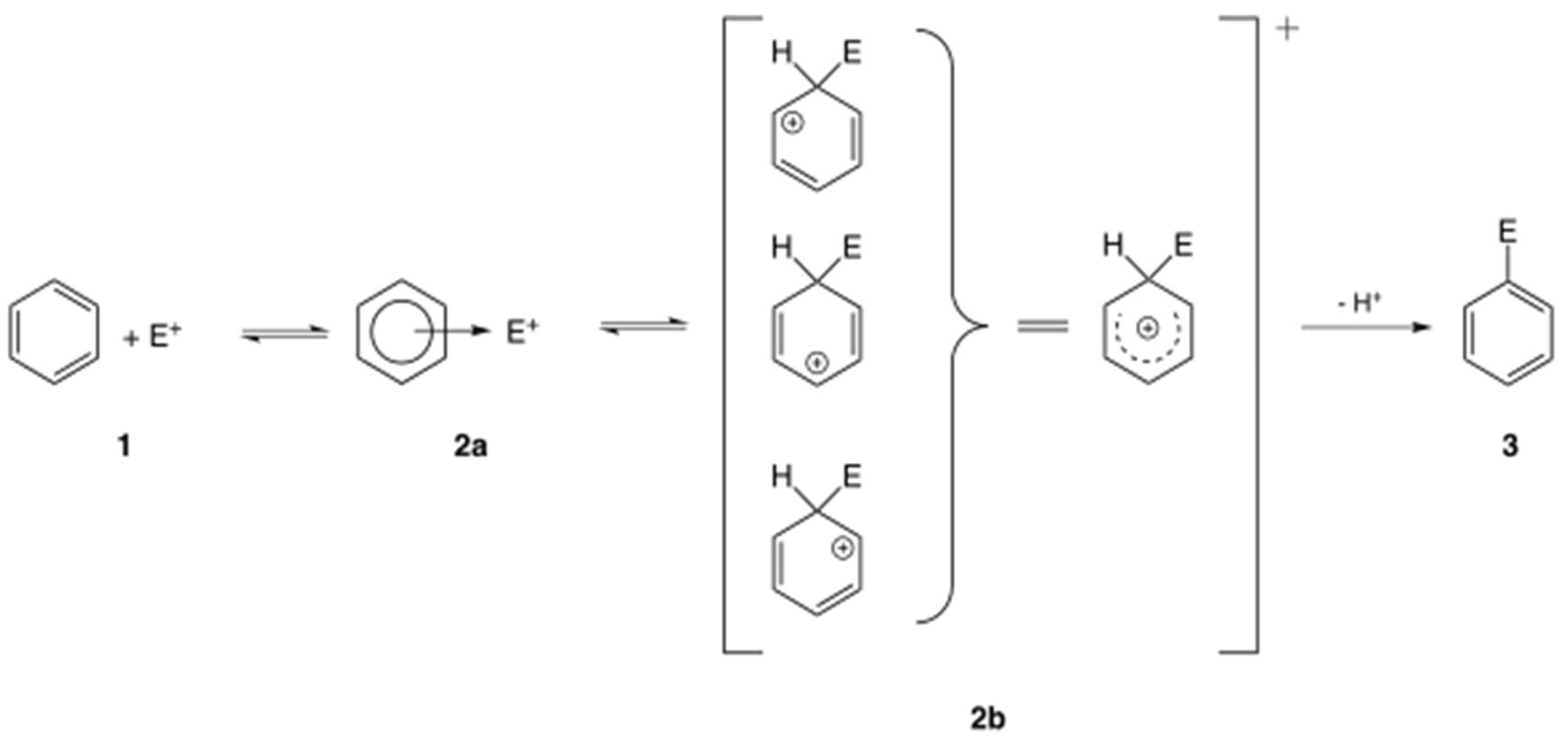

- Wheland G. W. A quantum mechanical investigation of the orientation of substituents in aromatic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1942, 64(4), p. 900-908. [CrossRef]

- Groeger A.L., Freeman B.A. Signaling actions of electrophiles: anti-inflammatory therapeutic candidates. Mol. Interv. 2010, 10(1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, N. L. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009, 49, 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque E.C., Pereira E.F.R., Alkondon M., Rogers S.W. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 73–120. [CrossRef]

- Mishra A., Chaturvedi P., Datta S., Sinukumar S., Joshi P. et al. Harmful effects of nicotine, Ind. Med. Paed. Onc. 2015, 36, 1.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Harmful and potentially harmful constituents in tobacco products and tobacco smoke: established list. 2012, 20034-20037. http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm297786.htm.

- Yarden, Y., Pines, G. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2012, 12, 553-563.

- Zhong L., Li Y., Xiong L., Wang W., Wu M. et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 201, 2021.

- Sies H., Belousov V.V., Chandel N.S., Davies M.J., Jones D.P. et al. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 499-515. [CrossRef]

- Casas A.I., Nogales C., Mucke H.A.M., Petraina A., Cuadrado A. et al. On the clinical pharmacology of reactive oxygen species. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 801-828. [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi P., Jaquet V., Marcucci F., Schmidt H.H.H.W. The oxidative stress theory of disease: levels of evidence and epistemological aspects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174(12), 1784-1796. [CrossRef]

- Manning G., Whyte D.B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science, 2002, 298, 1912–1934.

- Sohn H.S., Kwon J.W., Shin S., Kim H.S., Kim H. Effect of smoking status on progression-free and overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving erlotinib or gefitinib: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 661-671. [CrossRef]

- Kroeger N., Li H., De Velasco G., Donskov F., Sim H.W. et al. Active smoking is associated with worse prognosis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with targeted therapies. Clin. Genitourinary Cancer, 2019, 17, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Saad E., Gebrael G., Semaan K., Eid M., Saliby R.M. et al. Impact of smoking status on clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor-based regimens. Oncologist, 2024, 29, 699-706. [CrossRef]

- Sakanyan V., Alves de Sousa R. Why hydrogen peroxide-producing proteins are not suitable targets for drug development. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Oncology, 2024, 11, 1, 104.

- Samimi A., Khodayar M.J., Alidadi H., Khodadi E. The dual role of ROS in hematological malignancies: stem cell protection and cancer cell metastasis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep., 2020, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis A., Vlachogianni T., Fiotakis K. Tobacco smoke: Involvement of reactive oxygen species and stable free radicals in mechanisms of oxidative damage, carcinogenesis and synergistic effects with other respirable particles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2009, 6, 445-462; [CrossRef]

- Busch C., Jacob C., Anwar A., Burkholz T., Aicha Ba L. et al. Diallylpolysulfides induce growth arrest and apoptosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 36, 743–749.

- Boukhenouna S., Wilson M.A., Bahmed K., Kosmider B. Reactive oxygen species in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 5730395.

- Seo Y-S., Park J-M., Kim J-H., Lee M-Y. Cigarette smoke-induced reactive oxygen species formation: A concise review. Antioxidants, 2023, 12, 1732. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen C.E., Carroll K.S. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: Chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4633–4679.

- Marzo N.D., Chisci E., Giovannoni R. The role of hydrogen peroxide in redox-dependent signaling: Homeostatic and pathological responses in mammalian cells. Cells 2018, 7, 156. [CrossRef]

- Lennicke C., Rahn J., Lichtenfels R., Ludger A. Wessjohann L.A., Seliger B. Hydrogen peroxide – production, fate and role in redox signaling of tumor cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 39. [CrossRef]

- Hattori Y., Nishigori C., Tanaka T., Ushida K., Nikaido O. et al. 8-Hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine is increased in epidermal cells of hairless mice after chronic ultraviolet B exposure. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1996, 107, 733-737. [CrossRef]

- Lonkar P., Dedon P.C. Reactive species and DNA damage in chronic inflammation: reconciling chemical mechanisms and biological fates. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 1999−2009.

- Lobo V., Patil A., Phatak A., Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Sena L.A., Chandel N.S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell, 2012, 48, 158−167.

- Sheng Y., Abreu I.A., Cabelli D.E., Miller A-F., Teixeira M. et al. Superoxide dismutases and superoxide reductases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7, 3854–3918. [CrossRef]

- Gropper S.S., Smith J.L., Carr T.P. Advanced nutrition and human Metabolism, 7th Ed,,Cengage Learning Inc., Wadsworth, 2017.

- Kocot J., Kiełczykowska M., Luchowska-Kocot D., Kurzepa J., Musik I. Antioxidant potential of propolis, bee pollen, and royal jelly: possible medical application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 707420. [CrossRef]

- Martinello M., Mutinelli F. Antioxidant activity in bee products: A review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021, 10, 71. [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi A.M., Pop A., Iordache F., Stanca L., Predoi G. et al. Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants - an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 2021, 209, 112891.

- Perillo B., Di Donato M., Pezone A., Di Zazzo E., Giovannelli P., Galasso G., Castoria G., Migliaccio A. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52(2), 192-203. [CrossRef]

- Cyran A.M., Zhitkovich A. HIF1, HSF1, and NRF2: Oxidant-responsive trio raising cellular defenses and engaging immune system. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Moi P., Chan K., Asunis I., Cao A., Kan Y.W. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9926-9930. [CrossRef]

- Joshi G., Johnson J.A. The Nrf2-ARE pathway: a valuable therapeutic target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2012, 7(3), 218-229. [CrossRef]

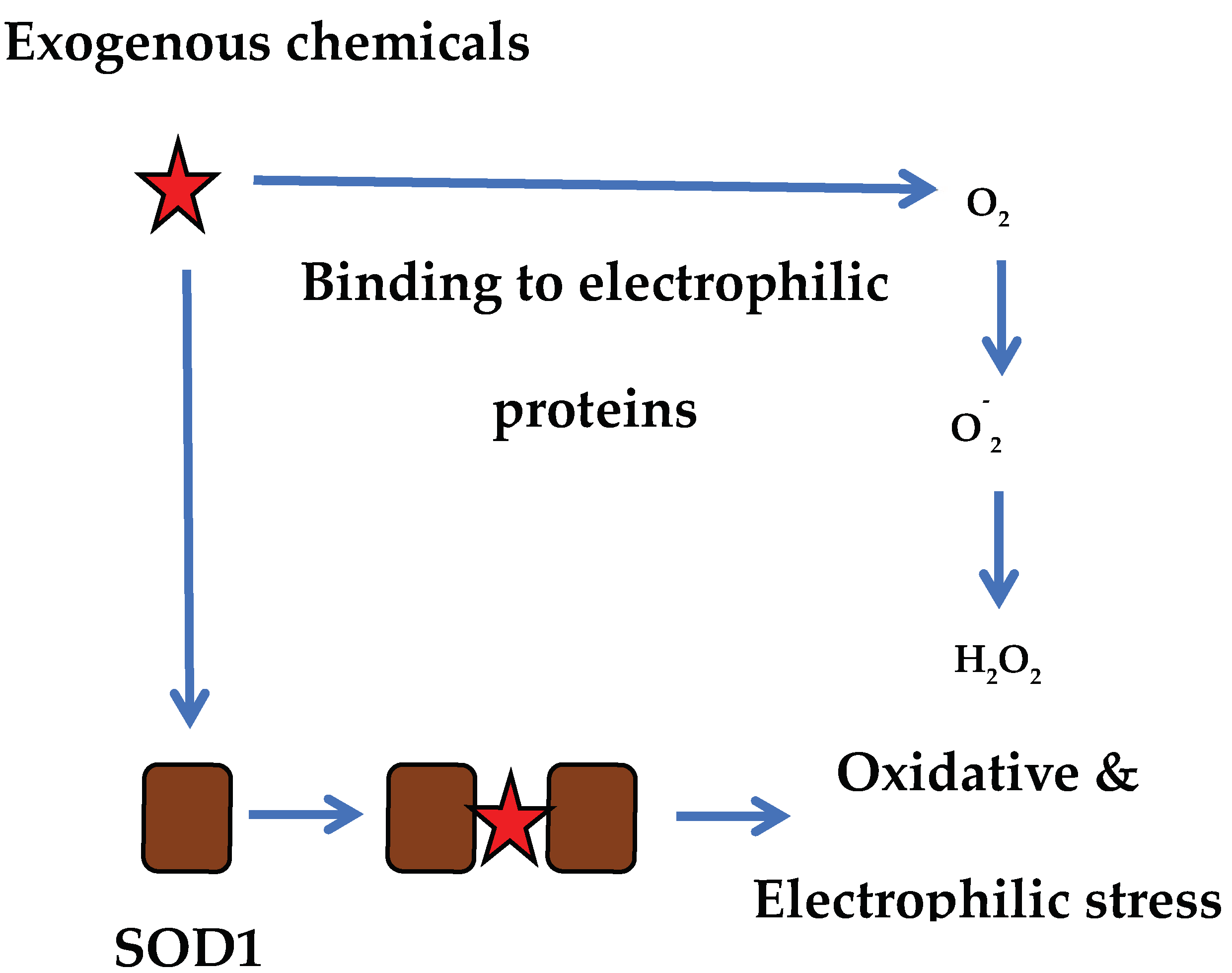

- Unoki T., Akiyama M., Kumagai Y. Nrf2 activation and its coordination with the protective defense systems in response to electrophilic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 545. [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi O., Dabirmanesh B., Ghazi F., Amanlou M., Atabakhshi-Kashi M., Fathollahi Y., Khajeh K. The effect of Nrf2 deletion on the proteomic signature in a human colorectal cancer cell line. BMC Cancer, 2022, 22(1), 979. [CrossRef]

- Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Superoxide dismutases: role in redox signaling, vascular function, and diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1583-1606. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli C., Chio I.I.C., Tuveson D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29(17), 1727-1745. [CrossRef]

- Radi R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115(23), 5839-5848. [CrossRef]

- Akaike T., Nishida M., Fujii S. Regulation of redox signalling by an electrophilic cyclic nucleotide. J. Biochemistry, 2013, 153, 2, 131-138. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg F., Ramnath N., Nagrath D. Reactive oxygen species in the tumor microenvironment: An overview. Cancers 2019, 11, 1191. [CrossRef]

- Sakanyan V., Hulin P., Alves de Sousa R., Silva V., Hambardzumyan A. et al. Activation of EGFR by small compounds through coupling the generation of hydrogen peroxide to stable dimerization of Cu/Zn SOD1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21088. [CrossRef]

- Sakanyan V., Benaiteau F., Alves de Sousa R., Pineau C., Artaud I. Straightforward detection of reactive compound binding to multiple proteins in cancer cells: Towards a better understanding of electrophilic stress. Ann. Clin. Exp. Metabol. 2016, 1, 1006.

- Sakanyan V. Reactive chemicals and electrophilic stress in cancer: A minireview. High-Throughput 2018, 7, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T., Joubert P., Ansari-Pour N., Zhao W., Hoang P.H. et al. Genomic and evolutionary classification of lung cancer in never smokers. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1348–1359. [CrossRef]

- Frankell A.M., Dietzen M., Bakir M.A., Lim E.L., Karasaki T. et al. The evolution of lung cancer and impact of subclonal selection in TRACERx. Nature, 2023, 616, 525-533. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X., Zeng W., Rong S., Lv H., Chen Y. et al. Alendronate-modified nanoceria with multiantioxidant enzyme-mimetic activity for reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species scavenging from cigarette smoke. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 47394-47406. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q., Zhao S., Zhang Y., An X., Wang Q. et al. Biochar nanozyme from silkworm excrement for scavenging vapor-phase free radicals in cigarette smoke. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2022, 5, 1831-1838. [CrossRef]

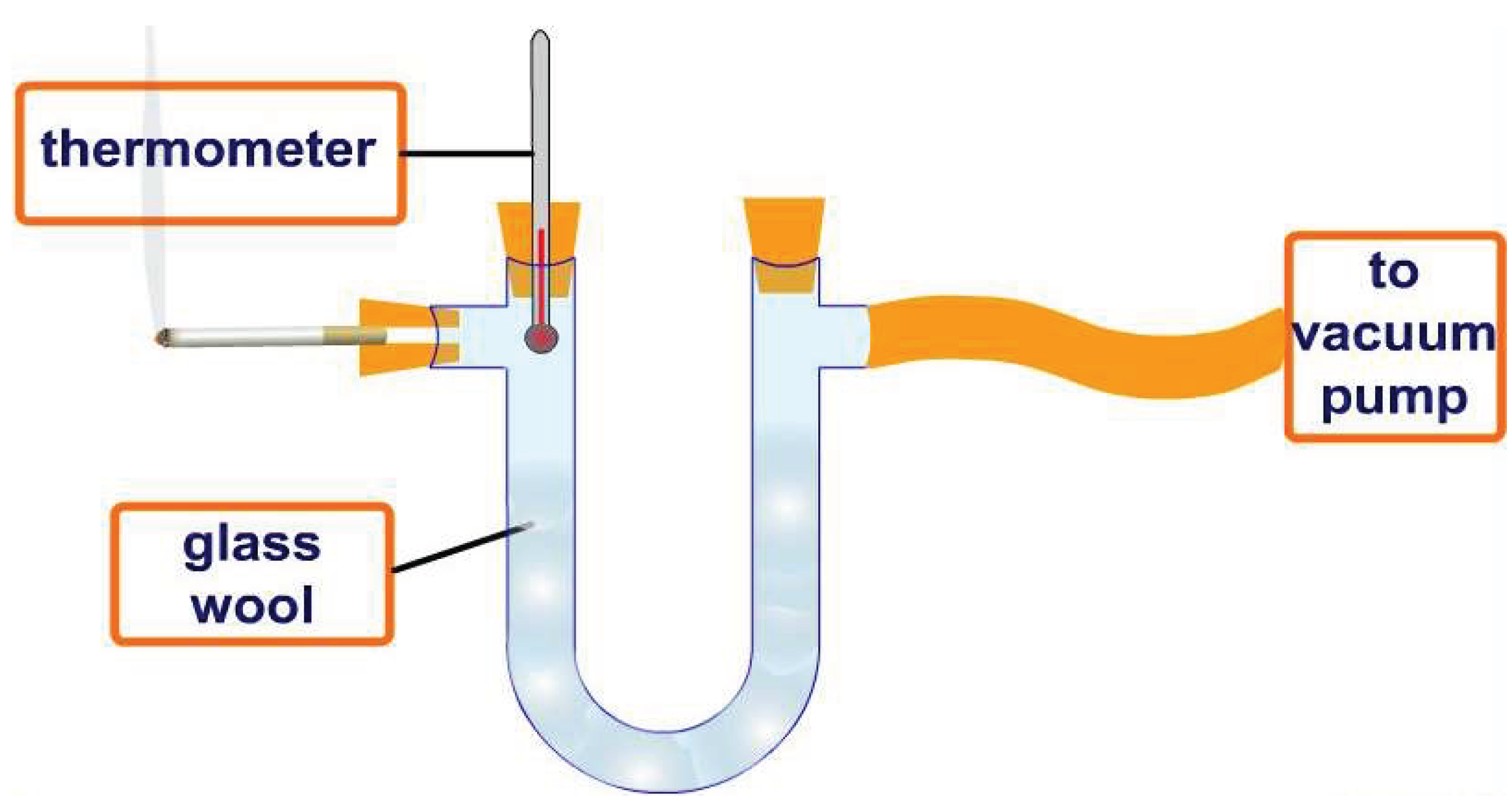

- Aghajanyan A.E., Hambardzumyan A.A., Minasyan E.V., Hovhannisyan G.J., Yeghiyan K.I. Efficient isolation and characterization of functional melanin from various plant sources. Inter. J. Food Scie. Tech. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Geiss, D. Kotzias. Tobacco, cigarettes and cigarette smoke: An overview. Euro. Com., Dir. Gen., Joint Res. Centre. 2007, EUR 22783 EN.

- Madani A., Alack K., Richter M.J., Kruger K. Immune-regulating effects of exercise on cigarette smoke-induced inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 11, 155−167.

- Wu Z., Xia F., Lin, R. Global burden of cancer and associated risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1980–2021: a systematic analysis for the GBD 2021. J. Hematol. Oncol .17, 2024, 119. [CrossRef]

- Caliri A.W., Tommasi S., Besaratinia A. Relationships among smoking, oxidative stress, inflammation, macromolecular damage, and cancer. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 787, 108365. [CrossRef]

- Caini S., Del Riccio M., Vettori V., Scotti V., Martinoli C., et al. Quitting smoking at or around diagnosis improves the overall survival of lung cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac Oncol. 2022, 17, 623-636. [CrossRef]

- Cinciripini P.M., Kypriotakis G., Blalock J.A., Karam-Hage M., Beneventi D.M. et al. Survival outcomes of an early intervention smoking cessation treatment after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1689-1696. [CrossRef]

- Cinciripini P.M., Kypriotakis G., Blalock J.A., Karam-Hage M., Beneventi D.M. et al. Survival outcomes of an early intervention smoking cessation treatment after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1689-1696.

- Lowy D.R., Fiore M.C., Willis G., Mangold K.N., Bloch M. H. et al. Treating smoking in cancer patients: An essential component of cancer care - the new National cancer institute tobacco control monograph. JCO Onc. Pract., 2022, 18, 12, 1971-1976. [CrossRef]

- Davis B., Williams M., Talbot P. iQOS: evidence of pyrolysis and release of a toxicant from plastic. Tobacco Control, 2019, 28, 334-410.

- Shehata S.A., Toraih E.A., Ismail E.A., Hagras A.M., Elmorsy E. et al. Environmental toxicants exposure, and lung cancer risk. Cancers 2023, 15, 4525. [CrossRef]

- Kundu A., Sachdeva K., Feore A., Sanchez S., Sutton M. et al. Evidence update on the cancer risk of vaping e-cigarettes: A systematic review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2025, 23, 6. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Optical Density of DPPH Solution |

|---|---|

| Water-alcohol solution of DPPG | 1,198 |

| Original iqos cigarette | 0,379 |

| Filter treated with water | 0,355 |

| Filter impregnated with grape melanin | 0,199 |

| Compound | µg/Cig. |

|---|---|

| Nicotine | 100-3000 |

| Nornicotine | 5-150 |

| Anatabine | 5-15 |

| Anabasine | 5-12 |

| Total non-volatile HC | 300-400 |

| Naphthalenes | 3-6 |

| Pyrenes | 0.3-0.5 |

| Phenol | 80-160 |

| Other Phenols | 60-180 |

| Catechol | 200-400 |

| Other Catechols | 100-200 |

| Other Dihydroxybenzenes | 200-400 |

| Palmitic Acid | 100-150 |

| Quinones | 0.5 |

| Solanesol | 600-1000 |

| Linoleic Acid | 150-250 |

| Indole | 10-15 |

| Quinolines | 2-4 |

| Benzofurane | 200-300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).