1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a vital force for economic development, driving innovation, competition, and societal adaptation (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004). Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), capturing the prevalence of nascent and new business owners, serves as a critical indicator of this dynamism at a national level (Bosma & Kelley, 2019), making its determinants a key area of inquiry. In the 21st century, the entrepreneurial engine operates within two transformative contexts: the escalating importance of sustainability, captured by Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria (Bacq & Aguilera, 2022; Eccles et al., 2014), and the pervasive influence of rapid technological change, including advancements like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and new digital ecosystems (Nambisan, 2017; Popkova & Sergi, 2020). Understanding how these forces collectively shape the emergence of new ventures, particularly social entrepreneurship (SE) focused on social or environmental missions, is critical yet complex (Doherty et al., 2014).

While established datasets like the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and World Bank indicators provide valuable cross-country data (Acs et al., 2008), their extensive use necessitates research that moves beyond replication by offering significant innovation. This study addresses this need through a multi-pronged approach. Methodologically, it employs a rigorously selected panel regression model (Random Effects, justified in

Section 3.2) complemented by machine learning techniques (Random Forest, XGBoost) to explore dynamics and non-linearities often missed in simpler cross-sectional or less comprehensive panel analyses. Theoretically, it offers a novel synthesis by integrating insights from Technological Change Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and ESG frameworks to interpret the complex interplay between national ESG performance, the technological context, entrepreneurial ecosystem factors, and national TEA rates. Substantively, it aims to provide new insights into how these combined factors, particularly specific ESG dimensions, relate to overall entrepreneurial activity, with explicit consideration of the implications for social entrepreneurship.

Much existing research applies panel regression to explore TEA determinants (Aparicio et al., 2016), often focusing on narrower sets of institutional or macroeconomic variables. This study differentiates itself by examining a uniquely broad array of ESG indicators alongside detailed entrepreneurial ecosystem variables and technological proxies. The goal is not merely to identify correlates but to advance understanding by providing theoretically grounded explanations for observed associations and articulating the specific contribution to both general entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship literature, moving beyond incremental findings often associated with widely used datasets.

Specifically, this research addresses the following Research Questions (RQs):

RQ1: Which national-level ESG factors demonstrate a statistically significant association with national TEA rates, after controlling for country-specific heterogeneity using the selected Random Effects model?

RQ2: How do internal entrepreneurial ecosystem variables relate to national TEA when assessed concurrently with external ESG factors in a panel framework?

RQ3: How can established theories (Technological Change, Stakeholder Theory) help interpret the observed significant relationships between specific ESG indicators and TEA?

RQ4: Do AI-driven models identify similar or different key predictors for TEA compared to the linear Random Effects panel model, suggesting potential non-linearities or complex interactions?

By addressing these questions, this study aims to advance understanding beyond existing panel studies by explicitly linking a broad set of ESG factors to TEA within a synthesized theoretical framework and employing methodological rigor. The principal conclusions highlight the significant association of strong governance, social investments, and internal ecosystem dynamics with national TEA rates, offering nuanced implications for policy aimed at fostering resilient and impactful entrepreneurship.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources, Country Selection, and Justification

This study utilizes panel data constructed from established, publicly available sources: the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) for entrepreneurship variables and the World Bank's World Development Indicators (WDI) and Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for ESG and macroeconomic variables. The selection of these datasets, while common (Acs et al., 2008; Bosma & Kelley, 2019), is justified here by the specific research aim: to conduct a novel synthesis integrating a uniquely comprehensive set of ESG, technological context proxies, and ecosystem variables simultaneously, analyzed via robust panel methods and machine learning. This integrated approach, focusing on the interplay between these domains, aims to provide insights beyond studies using narrower variable sets or simpler methodologies.

Country Selection Criteria: The final panel includes 45 countries selected based primarily on consistent data availability across the core GEM surveys, WDI, and WGI datasets for the target period (2009-2023). This ensures a balanced panel structure suitable for the intended regression analysis. While not explicitly stratified, the resulting sample includes countries representing diverse geographic regions and levels of economic development, enhancing the potential generalizability of findings, although caution is warranted given the availability-driven selection. The analysis covers the period 2009 to 2023, yielding 631 country-year observations after processing.

2.2. Variables

The primary outcome of interest, serving as the dependent variable, is the Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) rate (entrepreneurial_tea). This metric is defined as the percentage of the 18–64 population actively involved in either starting a nascent venture or running a new business operational for less than 42 months (Bosma & Kelley, 2019). TEA was chosen as the dependent variable because it represents a widely accepted and crucial measure of the overall entrepreneurial dynamism and venture creation rate within a national economy.

A wide array of independent variables was considered for the analysis, drawn from the merged dataset and representing distinct theoretical domains pertinent to entrepreneurship. These encompass several categories, including Environmental Indicators (such as coastal_protection and renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output), Social Indicators (like economic_and_social_rights_performance_score, government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure, income_share_held_by_lowest_20, and school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi), and Governance Indicators (for instance, rule_law_estimate and control_corruption_estimate). Additionally, variables characterizing the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem & Contextual Factors (e.g., entrepreneurial_intentions, entrepreneurial_employee_activity, female_male_tea, high_job_creation_expectation, and individuals_using_the_internet_population) were included, alongside standard Control Variables such as gdp_growth_annual. The full list of variables incorporated into the final model specification is detailed in

Table 2 (Results section).

2.3. Data Processing

Data preprocessing involved standardizing country names and column headers, ensuring correct data types, and merging the datasets by country and year. The TEA variable was treated as a continuous percentage. No missing values were present in the final set of variables used for the primary Random Effects model analysis presented, obviating the need for imputation techniques for these specific results.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Given the longitudinal and cross-sectional nature of the dataset (multiple countries over multiple years), panel data regression was selected as the core analytical approach, utilizing the linearmodels Python library (Kerby, 2023). This methodology is advantageous as it allows for controlling unobserved, time-invariant country-specific heterogeneity (via Fixed or Random Effects) and potentially common time trends (via Time Effects) that could significantly bias estimates derived from simple OLS or cross-sectional approaches (Baltagi, 2021; Wooldridge, 2010).

The model selection rationale involved a systematic process based on established diagnostic tests to determine the most statistically appropriate and efficient specification for this specific dataset, with outcomes summarized in Results (

Section 3.2,

Table 1). This process included an F-test for poolability to assess if entity-specific effects were jointly significant compared to Pooled OLS, an F-test for time effects to determine if including time dummies significantly improved the model fit over an entity-only effects model, and a Hausman test to compare the consistency and efficiency of Random Effects versus Fixed Effects estimators by testing the assumption of no correlation between unobserved entity effects and regressors. The collective results of these tests, detailed in

Section 3.2.1, guided the selection of the Random Effects model as the primary specification for this analysis.

Regarding multicollinearity assessment and robustness measures, Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were calculated for the independent variables in the final model specification to diagnose potential multicollinearity issues, with details provided in

Section 3.2. Crucially, to ensure the reliability of the findings, all panel estimations employed country-clustered standard errors. This approach provides more robust inference by adjusting for potential correlations within countries over time (serial correlation) and non-constant variance across countries (heteroskedasticity), which are common challenges in macroeconomic panel data.

As a form of complementary machine learning analysis, the panel regression was supplemented with Random Forest (Breiman, 2001) and XGBoost (Chen & Guestrin, 2016) models. These were employed to explore potential non-linear relationships and offer an alternative perspective on predictor importance beyond the assumptions of linear regression. The machine learning models were optimized using GridSearchCV and k-fold cross-validation, and feature importances derived from them provide insights into predictive relevance without imposing linearity assumptions.

3. Results: Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

3.1. ESG and Entrepreneurship

The relationship between environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns and entrepreneurship is increasingly acknowledged as vital to sustainable development and responsible innovation (Bacq & Aguilera, 2022; Hall et al., 2010). Environmental factors include resource efficiency and climate adaptation, which can encourage green entrepreneurship (Dean & McMullen, 2007). However, the financial implications, such as the impact of ESG risk ratings on stock performance in specific sectors like electric vehicle manufacturing, demonstrate the complex interplay between sustainability efforts and market valuation (Onomakpo, 2025a). Social factors, including education and labor rights, shape the human capital and societal conditions for entrepreneurial pursuits (Naudé, 2010). Governance, particularly the rule of law, forms an essential institutional bedrock upon which entrepreneurs rely (Aidis et al., 2008). The integration of ESG considerations reflects a broader understanding of businesses as entities with impacts beyond purely financial returns (Eccles et al., 2014).

3.1.1. Theory of Technological Change and Its Entrepreneurial Implications

Theories of technological change emphasize how innovations drive economic transformations and create new entrepreneurial opportunities (Acs & Audretsch, 1988). More recent perspectives explore how different technological shifts can differentially affect skill demand (Ales et al., 2021) and the scaling of social ventures, questioning if the technological environment is a critical factor (Anokhin & Eggers, 2023). Agbenyo (2020) analyzes technology's successes and failures through structural change theory. These theories suggest that adopting new technologies (e.g., AI, IoT) fundamentally alters the entrepreneurial landscape, influencing opportunity recognition and venture creation processes. Furthermore, the pursuit of tech-driven circularity, leveraging agile and lean synergies, presents novel pathways for sustainable innovation and new venture creation by rethinking resource use and production processes (Onomakpo, 2025c). The impact of technological change on national TEA rates is likely multifaceted.

3.1.2. Stakeholder Theory and Its Relevance to Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Stakeholder theory posits that organizations should consider all legitimate stakeholder interests for long-term success (Freeman, 1984; Mahajan et al., 2023). This is relevant for entrepreneurial ecosystems, where interactions with diverse actors are crucial (Shah & Guild, 2022). Bacq & Aguilera (2022) propose stakeholder governance for responsible innovation. In technological change, stakeholder theory helps analyze how firms engage stakeholders for innovation. For entrepreneurs, managing stakeholder relationships is key to accessing resources and legitimacy. Indeed, innovation pathways focusing on value capture through collaboration, such as those observed in national innovation systems like Norway's, highlight the practical application of stakeholder engagement for achieving entrepreneurial success and broader economic benefits (Onomakpo, 2025b). Narratives of collective social entrepreneurs also emphasize bridging disconnections within networks (Manjon et al., 2024).

3.1.3. The Evolving Role of AI, IoT, and Digital Technologies in Shaping Entrepreneurship

The rapid advancement of AI, IoT, and other digital technologies profoundly reshapes entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017). AI offers transformative potential from opportunity recognition to operational efficiency (Popkova & Sergi, 2020). IoT enables interconnected devices, fostering new business models (Lubberink, 2020). These technologies can lower entry barriers but also create challenges related to data privacy, ethics (Bardaa, 2025), and digital skills. The connection between people and AI is an increasingly important component of current jobs and venture creation (Canestrino et al., 2024).

3.1.4. Social Entrepreneurship Within Digital Ecosystems (Metaverse, Digital Twin)

Social entrepreneurship (SE) is broadly understood as entrepreneurial activity with an embedded social purpose, aiming to create significant social or environmental impact, often alongside financial sustainability (Mair & Marti, 2006; Doherty et al., 2014). SE is increasingly leveraging emerging digital ecosystems. The metaverse and immersive virtual worlds offer new platforms for SEs to engage beneficiaries and deliver services (Al-Omoush et al., 2024; Devereaux, 2021). These technologies can facilitate novel forms of value co-creation (García-Morales et al., 2020). However, the "digital Wild West" nature of some platforms also presents challenges regarding accessibility and ethics (Devereaux, 2021).

3.1.5. Impact Measurement, Fidelity, and Scaling in Social Entrepreneurship

A core challenge for SE is robustly measuring and scaling social impact (Islam, 2020). Unlike traditional businesses, SEs must demonstrate complex social/environmental value creation (Feichtinger, 2024). "Impact fidelity" refers to maintaining the core social mission as a venture scales. Scaling strategies for SEs are multifaceted (Ballesteros-Sola & Raible, 2024), with pathways often influenced by organizational capabilities, especially in emerging economies (Xiao, 2025). Effective scaling often requires attracting aligned impact investment (Borrello et al., 2023), where investors evaluate social enterprises through specific frameworks (Agrawal & Jespersen, 2023). Building strong social capital (Mohiuddin et al., 2023) and navigating legitimacy processes are also crucial for scaling social enterprises (Khare et al., 2024). The technological environment itself can also moderate the scaling of social ventures (Anokhin & Eggers, 2023).

3.2. Panel Regression: Descriptive Statistics and Multicollinearity Assessment

Descriptive statistics for key variables are provided in the Supplementary. The VIF analysis indicated moderate to high multicollinearity among several governance indicators (e.g., rule_of_law_estimate and control_corruption_estimate) and some socio-demographic variables. While all variables listed in

Table 1 (below) were retained for the RE model, the potential for inflated standard errors for highly correlated predictors was noted in the interpretation of individual coefficient significance.

3.2.1. Panel Model Selection Outcomes

As outlined in the statistical analysis approach (

Section 2.4), a systematic model selection process was undertaken. The outcomes, presented in

Table 1, led to the choice of the Random Effects (RE) model. Specifically, the F-test for poolability (F (44, 541) = 9.18, p < 0.0001) confirmed that entity effects are significant, thus rejecting the Pooled OLS model. The F-test for time effects (F (15, 526) = 0.49, p = 0.9442) showed that time effects were not jointly significant. Finally, the Hausman test (p = 0.5913) did not reject the null hypothesis that the RE model is consistent and efficient compared to a Fixed Effects specification, making RE the preferred model for this dataset.

Table 1.

Panel Model Selection Test Summary.

Table 1.

Panel Model Selection Test Summary.

| Test |

Statistic / Comparison |

P-value |

Implication |

| F-test for Poolability (Entity FE vs Pooled) |

F (44, 541) = 9.18 |

0.0000 |

Reject Pooled OLS; Entity Effects significant |

| F-test for Time Effects (2-Way vs Entity FE) |

F (15, 526) = 0.49 |

0.9442 |

Fail to Reject H0; Time Effects not jointly significant |

| Hausman Test (RE vs Entity FE) |

Chi2(df=?) = [Stat if calc.] |

0.5913* |

Fail to Reject H0; RE may be efficient |

3.2.2. Determinants of National Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity: Random Effects Model Findings

The Random Effects (RE) panel regression results, examining the association between various ESG, entrepreneurial ecosystem factors

, and national TEA rates, are presented in Table 2. The estimated model demonstrated a reasonable overall fit, explaining approximately 73.7% of the overall variance in TEA (Overall R² = 0.7369). The within-country variance explained by the model was 46.4% (Within R² = 0.4643).

Table 2.

Random Effects Panel Regression Results (Dependent Variable: entrepreneurial_tea).

Table 2.

Random Effects Panel Regression Results (Dependent Variable: entrepreneurial_tea).

| Feature |

Parameter |

Std. Err. |

T-stat |

P-value |

Sig. |

| Const |

4.12 |

3.41 |

1.21 |

0.23 |

|

| coastal_protection |

0.01 |

0.00 |

2.32 |

0.02 |

*** |

| control_corruption_estimate |

-0.90 |

0.67 |

-1.36 |

0.18 |

|

| economic_and_social_rights_performance_score |

0.24 |

0.12 |

2.06 |

0.04 |

*** |

| electricity_production_from_coal_sources_total |

0.00 |

0.01 |

-0.38 |

0.71 |

|

| energy_imports_net_energy_use |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-1.01 |

0.31 |

|

| energy_intensity_level_primary_energy_mj_2017_ppp_gdp |

0.09 |

0.13 |

0.72 |

0.47 |

|

| energy_use_kg_oil_equivalent_per_capita |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.73 |

0.46 |

|

| fertility_rate_total_births_per_woman |

-0.97 |

0.51 |

-1.90 |

0.06 |

. |

| food_production_index_2014_2016_100 |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-0.74 |

0.46 |

|

| fossil_fuel_energy_consumption_total |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.45 |

0.65 |

|

| gdp_growth_annual |

-0.02 |

0.02 |

-0.83 |

0.41 |

|

| gini_index |

0.04 |

0.02 |

1.52 |

0.13 |

|

| government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure |

0.07 |

0.03 |

2.37 |

0.02 |

*** |

| hospital_beds_per_1_000_people |

-0.08 |

0.06 |

-1.34 |

0.18 |

|

| income_share_held_by_lowest_20 |

-0.28 |

0.11 |

-2.61 |

0.01 |

**** |

| individuals_using_the_internet_population |

-0.02 |

0.01 |

-1.67 |

0.10 |

. |

| land_surface_temperature |

-0.04 |

0.03 |

-1.16 |

0.25 |

|

| level_water_stress_freshwater_withdrawal_as_a_proportion_available_freshwater_resources |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-1.44 |

0.15 |

|

| life_expectancy_at_birth_total_years |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.52 |

0.60 |

|

| literacy_rate_adult_total_people_ages_15_and_above |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.71 |

0.48 |

|

| people_using_safely_managed_sanitation_services_population |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.46 |

0.65 |

|

| political_stability_and_absence_violence_terrorism_estimate |

-0.16 |

0.40 |

-0.40 |

0.69 |

|

| population_ages_65_and_above_total_population |

-0.07 |

0.06 |

-1.13 |

0.26 |

|

| population_density_people_per_sq_km_land_area |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

|

| proportion_bodies_water_with_good_ambient_water_quality |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.10 |

0.92 |

|

| ratio_female_to_male_labor_force_participation_rate_modeled_ilo_estimate |

-0.02 |

0.02 |

-1.48 |

0.14 |

|

| renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output |

-0.02 |

0.01 |

-2.03 |

0.04 |

*** |

| renewable_energy_consumption_total_final_energy_consumption |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.13 |

0.90 |

|

| research_and_development_expenditure_gdp |

-0.06 |

0.14 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

|

| rule_law_estimate |

2.33 |

0.97 |

2.41 |

0.02 |

*** |

| school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi |

0.94 |

0.48 |

1.97 |

0.05 |

*** |

| voice_and_accountability_estimate |

-0.67 |

0.70 |

-0.94 |

0.35 |

|

| number_entrepreneur_llc |

0.00 |

0.00 |

-0.11 |

0.91 |

|

| perceived_opportunities |

0.00 |

0.02 |

-0.19 |

0.85 |

|

| perceived_capabilities |

0.04 |

0.03 |

1.59 |

0.11 |

|

| fear_failure_rate |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.09 |

0.93 |

|

| entrepreneurial_intentions |

0.30 |

0.05 |

5.83 |

0.00 |

***** |

| established_business_ownership |

0.13 |

0.10 |

1.30 |

0.19 |

|

| entrepreneurial_employee_activity |

0.34 |

0.10 |

3.31 |

0.00 |

**** |

| motivational_index |

0.02 |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.87 |

|

| female_male_tea |

4.25 |

1.44 |

2.94 |

0.00 |

**** |

| female_male_opportunity_driven_tea |

-0.90 |

0.96 |

-0.94 |

0.35 |

|

| high_job_creation_expectation |

0.06 |

0.03 |

2.03 |

0.04 |

*** |

| Innovation |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.54 |

0.59 |

|

| business_services_sector |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-2.19 |

0.03 |

*** |

| high_status_successful_entrepreneurs |

-0.04 |

0.02 |

-2.01 |

0.04 |

*** |

| entrepreneurship_good_career_choice |

0.02 |

0.02 |

1.19 |

0.24 |

|

Analysis of the coefficients reported in

Table 2 revealed several statistically significant associations with TEA at the conventional p < 0.05 level. Within the entrepreneurial ecosystem factors, entrepreneurial_intentions (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), entrepreneurial_employee_activity (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), the female_male_tea ratio (β = 4.25, p < 0.001), and high_job_creation_expectation (β = 0.06, p = 0.04) were all found to have significant positive associations with TEA.

Among governance and social factors, rule_law_estimate (β = 2.33, p = 0.02), economic_and_social_rights_performance_score (β = 0.24, p = 0.04), government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure (β = 0.07, p = 0.02), and school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi (β = 0.94, p = 0.05) were positively associated with TEA. Conversely, income_share_held_by_lowest_20 (β = -0.28, p = 0.01) exhibited a significant negative association.

Regarding environmental and other contextual factors, coastal_protection (β = 0.01, p = 0.02) was positively linked to TEA. In contrast, renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output (β = -0.02, p = 0.04), business_services_sector (β = -0.07, p = 0.03), and high_status_successful_entrepreneurs (β = -0.04, p = 0.04) demonstrated significant negative associations with TEA.

Additionally, variables such as fertility_rate_total_births_per_woman (p = 0.06) and individuals_using_the_internet_population (p = 0.10) showed borderline significance at the p < 0.10 level.

3.2.3. Predictive Insights from Machine Learning Models

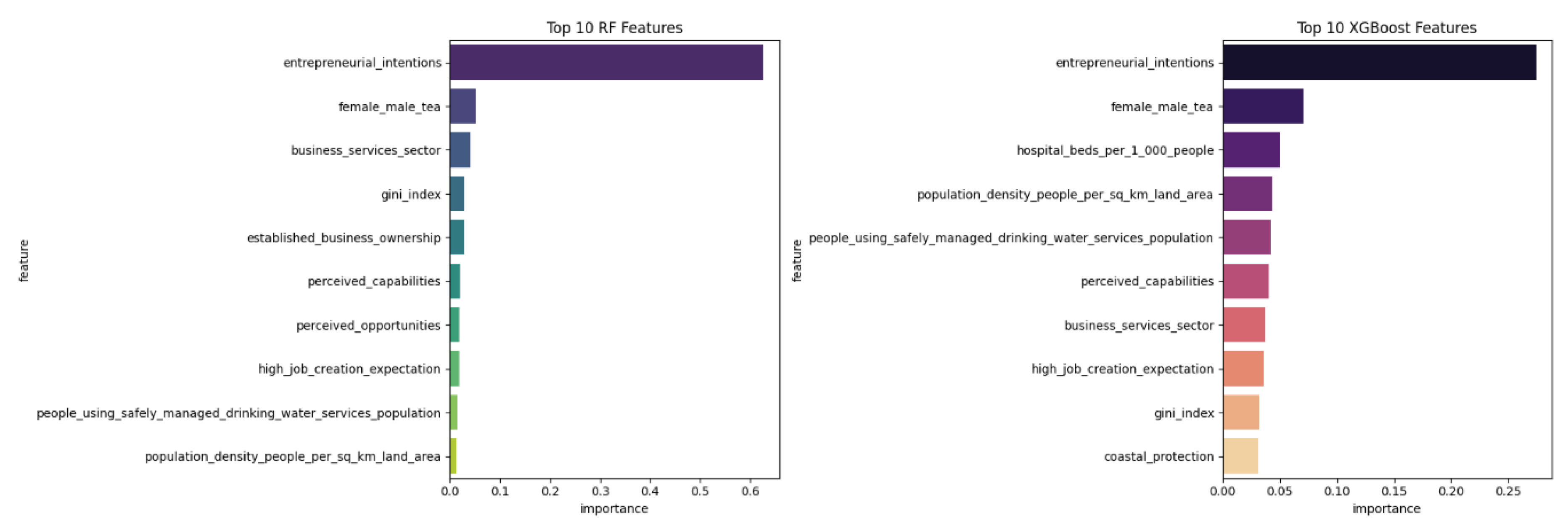

To complement the panel regression analysis and explore predictor relevance from alternative methodological perspectives, Random Forest and XGBoost models were employed.

The relative importance of predictor variables, as determined by both the Random Forest and XGBoost algorithms, is presented comparatively in the bar chart shown in

Figure 1. Examination of

Figure 1 indicated that entrepreneurial_intentions was identified as the most important feature by both models, although its relative importance score differed between them (RF Importance ≈ 0.63; XGBoost Importance ≈ 0.16). Other variables, such as perceived_capabilities, female_male_tea, high_job_creation_expectation, and business_services_sector, also appeared among the top predictors for at least one of the models, as detailed comparatively in

Figure 1.

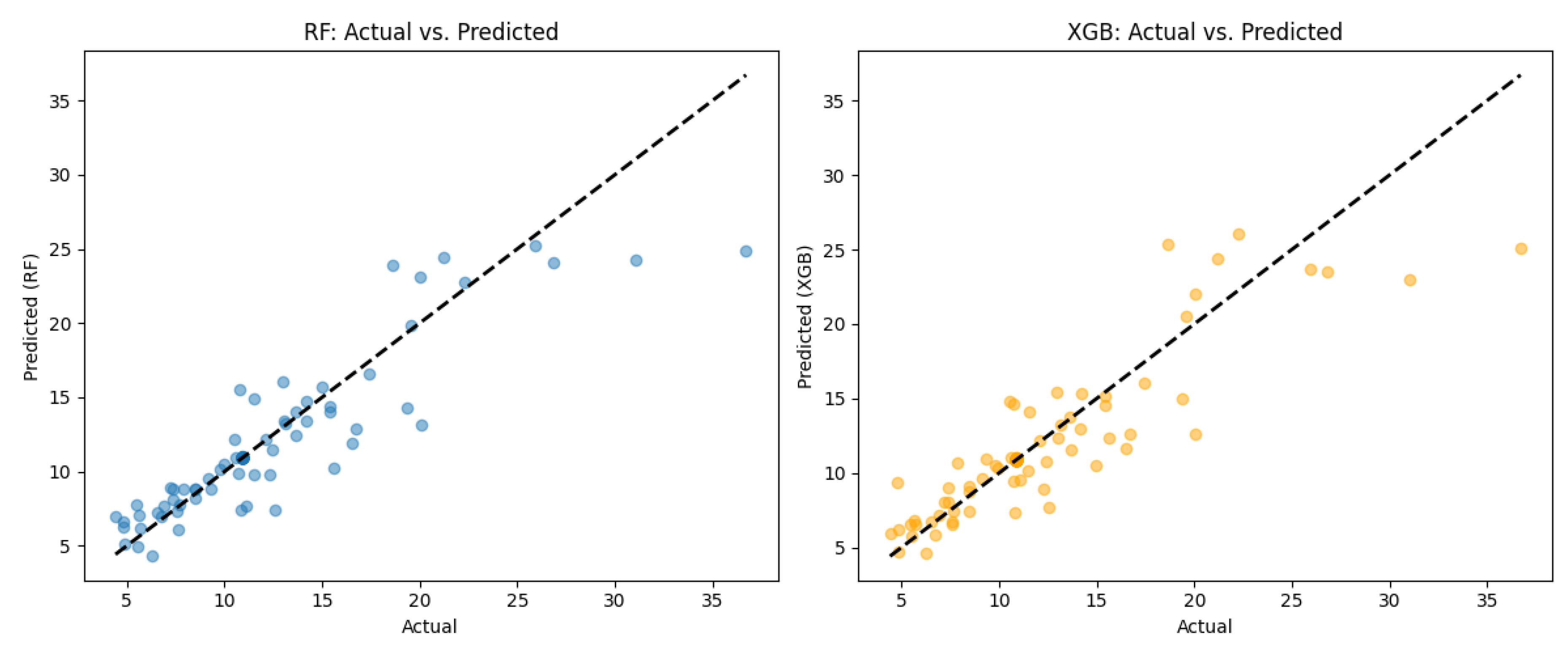

Additionally, the predictive performance of the trained Random Forest and XGBoost models is visualized in

Figure 2, which displays scatter plots comparing the models' predicted TEA values against the actual TEA values for the test dataset.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of predictions around the line of perfect fit for both the Random Forest and XGBoost models, providing a visual assessment of their predictive accuracy on unseen data.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to provide a synthesized analysis of how national-level Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors, considered alongside the internal entrepreneurial ecosystem and proxies for the technological context, are associated with Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), using established datasets (GEM, World Bank) but employing a methodologically rigorous and theoretically integrated approach. The findings from the Random Effects (RE) panel regression model (

Table 2), selected through systematic diagnostic testing (

Table 1), alongside complementary insights from machine learning models (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), offer several points for discussion in light of the research questions and existing literature.

4.1. The Dominant Role of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (Addressing RQ2)

Confirming a substantial body of literature derived from GEM data (Bosma & Kelley, 2019), the analysis underscores the critical importance of factors intrinsic to the entrepreneurial ecosystem concerning national TEA rates (RQ2). The variable entrepreneurial_intentions emerged as the most significant positive predictor in the RE model (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) and was overwhelmingly dominant in the machine learning feature importance rankings (

Figure 1). This highlights its role as a crucial precursor to action, representing the pool of potential entrepreneurs within a population. Similarly, entrepreneurial_employee_activity (EEA) showed a strong positive association (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), suggesting that intrapreneurial behavior within established firms may foster a broader entrepreneurial culture or provide skills and networks that spill over into new venture creation.

Furthermore, the significant positive coefficient for the female_male_tea ratio (β = 4.25, p < 0.001) indicates that greater gender parity in early-stage activity correlates strongly with higher overall national TEA. This suggests that national contexts enabling higher relative female participation tap into a larger entrepreneurial potential. The positive link between high_job_creation_expectation and TEA (β = 0.06, p = 0.04) points towards the perceived growth orientation often associated with opportunity-driven entrepreneurship captured within the TEA metric. These ecosystem-specific factors, representing individual perceptions, behaviors, and characteristics of the entrepreneurial activity itself, collectively show stronger associations in this model than many broader contextual factors, aligning with the high feature importance assigned to them by the predictive ML models (

Figure 1).

4.2. Interpreting ESG Dimensions: Governance and Social Pillars (Addressing RQ1 & RQ3)

Moving beyond the internal ecosystem, the study examined the association of specific ESG factors with TEA (RQ1), interpreted through relevant theoretical lenses (RQ3). The significant positive coefficient for rule_law_estimate (β = 2.33, p = 0.02) robustly supports institutional theory postulates, suggesting that stable, predictable, and fair legal environments are foundational for reducing uncertainty and encouraging venture creation (Aidis et al., 2008). From a Stakeholder Theory perspective (Freeman, 1984), strong rule of law safeguards diverse stakeholder interests (e.g., property rights, contract enforcement), fostering the trust and predictability necessary for investment and collaboration in new ventures (Bacq & Aguilera, 2022; Onomakpo, 2025b).

Significant positive associations were also found for several social investment indicators. The links between TEA and government_expenditure_on_education_total_government_expenditure (β = 0.07, p = 0.02), school_enrollment_primary_and_secondary_gross_gender_parity_index_gpi (β = 0.94, p = 0.05), and economic_and_social_rights_performance_score (β = 0.24, p = 0.04) empirically align with human capital theory and social development frameworks (Naudé, 2010). These results suggest that national investments in education, progress towards gender parity in schooling, and the upholding of broader economic and social rights create a more enabling environment, potentially by enhancing the skills, opportunities, and security needed for individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activities.

Conversely, the negative coefficient for income_share_held_by_lowest_20 (β = -0.28, p = 0.01) presents a more complex picture regarding equity. While greater societal equity is often considered beneficial, this finding, controlling for numerous other factors, might suggest that increases in the income share of the very poorest group may not directly translate into higher TEA rates as measured by GEM. This could be because the TEA metric predominantly captures more formal, opportunity-driven ventures less accessible to those escaping deep poverty, or that the level of income share, even if slightly increased, remains insufficient to overcome other barriers to entry. This finding warrants cautious interpretation and further investigation into the distinct effects of different types of inequality on necessity versus opportunity entrepreneurship.

4.3. Environmental Linkages and Other Contextual Factors (Addressing RQ1, RQ3, & RQ4)

The environmental dimension revealed nuanced associations. The positive link found for coastal_protection (β = 0.01, p = 0.02) is intriguing; it might serve as a proxy for broader investments in infrastructure quality, disaster preparedness, or climate adaptation measures that reduce systemic risks for businesses operating in coastal areas, thereby fostering a more stable environment for new ventures.

The negative coefficient observed for renewable_electricity_output_total_electricity_output (β = -0.02, p = 0.04) is counterintuitive relative to simplistic narratives about green growth driving entrepreneurship. This finding diverges from the general tenets of sustainable entrepreneurship emphasizing environmental opportunities (Dean & McMullen, 2007), but may reflect several underlying complexities. It could indicate that the high capital intensity or specific technological nature of large-scale renewable energy projects (often dominated by established players) does not directly translate into increased early-stage activity captured by TEA. Alternatively, it might reflect economic disruptions or adjustment costs associated with energy transitions in certain national contexts within the study period. This suggests that the relationship between renewable energy deployment and broad-based entrepreneurship is not straightforward and requires more granular investigation into the types of ventures and the maturity of the renewable energy sector.

Other contextual factors also showed significant negative associations. The coefficient for business_services_sector (β = -0.07, p = 0.03), representing the share of TEA involved in business services, might suggest that in economies where this sector is already prominent among new ventures, there could be market saturation effects or heightened competition, making entry for additional new ventures more challenging. Similarly, the negative link found for high_status_successful_entrepreneurs (β = -0.04, p = 0.04) is notable. While cultural esteem for entrepreneurship is often thought to be positive, this result could imply that a strong focus on a few high-profile "unicorns" doesn't necessarily correlate with higher rates of broad-based early-stage activity, or it might act as a proxy for more mature ecosystems where new entry rates are naturally lower.

Regarding the technological context (RQ4), proxies like individuals_using_the_internet_population showed only borderline significance in the RE model. However, the appearance of variables like perceived_capabilities (potentially influenced by digital literacy) as highly important in the XGBoost model (

Figure 2) hints that technology's influence might operate through indirect channels or exhibit non-linearities not fully captured by the linear panel model. This aligns with Technological Change Theory, suggesting that mere technology access is insufficient; its effective integration into skills and business models is likely key (Nambisan, 2017), a factor difficult to measure with available macro-level proxies.

4.4. Overall Contribution and Advancement of Knowledge

This study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by addressing the call for innovative analysis of established datasets like GEM and the World Bank. Its novelty lies specifically in the synthesis it provides across multiple dimensions. Firstly, regarding integrated scope, it simultaneously examines a broad array of ESG factors alongside detailed entrepreneurial ecosystem variables and technological context proxies, thereby moving beyond studies focused on narrower sets of determinants. Secondly, in terms of methodological rigor, this research applies panel data techniques featuring systematic, data-driven model selection (justifying the RE model for this specific dataset and variable set) and incorporates robustness checks such as clustered standard errors. Furthermore, the complementary use of machine learning models (Random Forest, XGBoost) offers additional insights into predictor importance and potential non-linearities, presenting a more comprehensive methodological perspective than panel regression alone. Thirdly, concerning theoretical integration, the study interprets findings through the combined lenses of Institutional Theory, Stakeholder Theory, Human Capital Theory, and Technological Change Theory, facilitating richer explanations for observed associations, especially for counter-intuitive results related to factors like income share or renewable energy output. By undertaking this synthesis, the study advances knowledge beyond many existing panel regression analyses in entrepreneurship, which often lack this breadth of variable integration, explicit methodological justification tailored to the data, or multi-theoretic interpretation. It consequently provides a more nuanced understanding of the multi-layered context shaping national entrepreneurial activity.

4.5. Implications for Social Entrepreneurship

While TEA measures general early-stage activity, the findings hold significant implications for the field of social entrepreneurship (SE). The strong positive associations found for rule_of_law_estimate, economic_and_social_rights_performance_score, and government_expenditure_on_education suggest that foundational governance quality, societal well-being, and human capital development are critical enabling conditions. These factors likely create more stable and resource-rich environments where SEs, often addressing deficits in these very areas, can emerge, gain legitimacy, and pursue scaling strategies (Khare et al., 2024; Manjon et al., 2024). The importance of factors like social capital and legitimacy processes for SE scaling (Mohiuddin et al., 2023) resonates with the finding that strong governance and social rights are positively associated with overall entrepreneurial activity.

Conversely, the complex finding regarding renewable_electricity_output might signal specific challenges for social entrepreneurs aiming to operate in the green energy space, potentially facing high capital barriers or competing with large incumbents. Similarly, the negative association with the relative prominence of the business_services_sector could indicate competitive pressures that might disproportionately affect SEs operating with dual missions. The potential moderating role of the technological environment on SE scaling (Anokhin & Eggers, 2023) underscores the need for SEs to effectively leverage digital tools and ecosystems (Al-Omoush et al., 2024; Devereaux, 2021). Understanding these contextual factors is crucial for designing support systems that effectively foster social venture creation and scaling (Agrawal & Jespersen, 2023; Ballesteros-Sola & Raible, 2024).

4.6. Policy Implications

The findings offer several nuanced implications for policymakers seeking to foster dynamic and sustainable national entrepreneurial ecosystems. Firstly, the strong significance of governance factors (rule_of_law) reinforces the importance of stable institutions, predictable regulations, and secure property rights as foundational elements. Secondly, investments in human capital (education expenditure, gender parity in schooling) and the upholding of economic and social rights appear strongly linked to higher TEA, suggesting that social development policies are also entrepreneurship policies. Thirdly, policies aimed solely at increasing the share of renewable energy might not automatically boost broad early-stage entrepreneurship; complementary measures addressing capital access, supporting smaller players, or managing transition costs may be necessary. Fourthly, while promoting high-growth ventures is important, fostering a broad base of entrepreneurial intentions and supporting female participation appear critical for overall TEA levels. Finally, the complex relationship with income distribution suggests that poverty reduction efforts need to be complemented by specific programs designed to enhance entrepreneurial opportunities for disadvantaged groups.

4.7. Limitations and Future Research

This study possesses several limitations that open avenues for future research. Firstly, the dependent variable, TEA, aggregates various types of entrepreneurship (necessity vs. opportunity, formal vs. informal, social vs. commercial) and does not provide a direct measure of social entrepreneurship activity. Future research using more granular or SE-specific outcome variables is needed. Secondly, while the RE model accounts for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity, potential endogeneity concerns (reverse causality or time-varying omitted variables) may remain for some predictors; advanced panel methods like dynamic GMM or carefully validated instrumental variable approaches could offer deeper causal insights, though finding suitable instruments is challenging. Thirdly, the high multicollinearity among some governance and socio-economic variables warrants caution in interpreting the independent effect of specific correlated predictors. Fourthly, the reliance on aggregate national-level data may mask significant sub-national variations. Lastly, the proxies used for the technological context (e.g., internet usage) are broad; future work should incorporate more nuanced metrics of digital transformation, AI adoption, and digital ecosystem maturity. Qualitative research could also provide deeper insights into the mechanisms behind the observed statistical relationships.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the multifaceted drivers of national Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) by synthesizing insights from ESG indicators, entrepreneurial ecosystem characteristics, and technological context proxies using panel data across 45 countries. Employing a rigorously selected Random Effects model complemented by machine learning techniques, the analysis sought to advance understanding beyond existing literature by integrating diverse theoretical perspectives and focusing on the interplay between these domains.

The principal findings confirm the paramount importance of the internal entrepreneurial ecosystem, with entrepreneurial_intentions, entrepreneurial_employee_activity, and the female_male_tea ratio exhibiting strong positive associations with national TEA rates. Crucially, the study also reveals significant links between TEA and specific ESG dimensions. Strong governance, particularly rule_of_law, and social investments, including government_expenditure_on_education, school_enrollment_gender_parity, and economic_and_social_rights, were positively associated with higher TEA. Conversely, some factors showed unexpected or complex relationships, such as the negative associations found for the income_share_held_by_lowest_20, the share of renewable_electricity_output, the prominence of the business_services_sector within TEA, and the perceived high_status_of_successful_entrepreneurs.

Theoretically, these findings lend support to institutional and human capital theories while highlighting the complex application of stakeholder theory and the nuanced role of environmental factors and technological diffusion in shaping national entrepreneurship levels. Methodologically, the study demonstrates the value of combining justified panel regression techniques with machine learning for analyzing complex, widely used datasets in entrepreneurship research.

Overall, this research contributes a nuanced perspective, emphasizing that fostering dynamic, sustainable, and potentially socially impactful entrepreneurship requires an integrated policy approach. Such an approach must consider not only the internal ecosystem dynamics but also the foundational importance of good governance, strategic social investments, and the complex realities of equity, environmental transitions, and technological integration within the national context. While acknowledging limitations, the synthesized analysis provides valuable insights for researchers and policymakers navigating the nexus of ESG, technology, and entrepreneurship.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; methodology, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; software, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; validation, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; formal analysis, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; investigation, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; resources, H.E.O.; data curation, H.E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; writing—review and editing, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; visualization, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; supervision, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo; project administration, Henry Efe Onomakpo Onomakpo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study, including the Python scripts used for analysis and the generated panel datasets, are available within the article or as

supplementary material associated with this publication, will be made available as

supplementary material on the publisher's website upon publication.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to the faculty and staff of the Faculty of Economics and Business for their support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Abbreviations

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| EEA |

Entrepreneurial Employee Activity (Implied by variable name) |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FE |

Fixed Effects |

| GEM |

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| RE |

Random Effects |

| RQs |

Research Questions |

| SE |

Social Entrepreneurship |

| TEA |

Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

| WDI |

World Development Indicators |

| WGI |

Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| XGB |

XGBoost (Implied by usage) |

References

- Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1988). Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis. The American Economic Review, 78(4), 678–690.

- Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Klapper, L. F. (2008). What does “entrepreneurship” data really show? Small Business Economics, 31(3), 265–281. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A., & Jespersen, K. (2023). How do impact investors evaluate an investee social enterprise? A framework of impact investing process. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16(4), 999-1022. [CrossRef]

- Agbenyo, J. S. (2020). The structural change theory–An analysis of success and failures of technology. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, IV(I), 2454-6186. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338685396_The_Structural_Change_Theory_-_An_Analysis_of_Success_and_Failures_of_Technology.

- Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. M. (2008). Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 656–672. [CrossRef]

- Ales, L., Combemale, C., Fuchs, E. R. H., & Whitefoot, K. S. (2021). How It's Made: A General Theory of the Labor Implications of Technology Change. Retrieved from https://www.christophecombemale.com/s/ACFW___How_It_s_Made___2022.pdf.

- Al-Omoush, K. S., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Lassala, C., & Skare, M. (2024). The impact of digital corporate social responsibility on social entrepreneurship and organizational resilience. Management Decision, 62(13), 118-143. [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, S., & Eggers, F. (2023). Social venture scaling: Does the technological environment matter? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 196, 122840. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S., Urbano, D., & Audretsch, D. B. (2016). Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, 45–61. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship and regional growth: An evolutionary interpretation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 14(5), 605–616. [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S., & Aguilera, R. V. (2022). Stakeholder governance for responsible innovation: A theory of value creation, appropriation, and distribution. Journal of Management Studies, 59(1), 29–60. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Sola, M., & Raible, S. (2024). Scaling Social Ventures. In De Gruyter Handbook of Social Entrepreneurship (pp. 531-544). De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. (2021). Econometric analysis of panel data (6th ed.). Springer.

- Bardaa, M. A. (2025). Social Entrepreneurship: A Synthesis of Concepts, Challenges, and Prospects. In Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Family Business for Inclusive Economic Growth. IGI Global.

- Borrello, A., Bengo, I., & Moran, M. (2023). How impact investing funds invest in social-purpose organizations: A cross-country comparison. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(2), 879-894. [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N., & Kelley, D. (2019). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. Retrieved from https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2018-2019-global-report.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Canestrino, R., Magliocca, P., & Ćwiklicki, M. (2024). Digital Transformation for a Better Society: The Role of Digital Social Entrepreneurship. In Humane Entrepreneurship in the Era of Digitalization. Emerald Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016, August). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 785–794). ACM. [CrossRef]

- Clark-Wilson, A., Bashir, A., & Kaye, T. (2021). A Theory of Change for a Technology-Enhanced Education System in Bangladesh. EdTech Hub. Retrieved from https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/2T7DPIBU.

- Daskalopoulou, I., Karakitsiou, A., & Thomakis, Z. (2023). Social entrepreneurship and social capital: A review of impact research. Sustainability, 15(6), 4787. [CrossRef]

- Dean, T. J., & McMullen, J. S. (2007). Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 50–76. [CrossRef]

- Devereaux, A. (2021). The digital Wild West: on social entrepreneurship in extended reality. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 10(2), 217–237. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [CrossRef]

- Feichtinger, C. (2024). Social entrepreneurship and performance measurement: a literature review of theoretical and empirical implications. In the Research Handbook on Sustainability Reporting. Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- García-Morales, V. J., Martín-Rojas, R., & Lardón-López, M. E. (2020). How to encourage social entrepreneurship action? Using Web 2.0 technologies in higher education institutions. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(2), 329–350. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. K., Daneke, G. A., & Lenox, M. J. (2010). Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5), 439–448. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. M. (2020). Unintended consequences of scaling social impact through ecosystem growth strategy in social enterprise and social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13, e00159. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., & Desa, G. (2022). Social entrepreneurship and impact investment in rural–urban transformation. In Social Innovation and Sustainability Transition. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Kerby, K. (2023). Panel Data Econometrics in Python: The LinearModels Package. Retrieved from https://bashtage.github.io/linearmodels/.

- Khare, P., Ghura, A. S., & Agrawal, A. (2024). A Process Model of Social Enterprise Scaling Using the Legitimacy Lens. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, ahead-of-print, 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M., & de Vries, R. A. J. (2021). Operationalizing behavior change theory as part of persuasive technology: A scoping review on social comparison. Frontiers in Computer Science, 3, 656873. [CrossRef]

- Lubberink, R. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and sustainable development. In Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R., Lim, W. M., Sareen, M., & Kumar, S. (2023). Stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Research, 169, 114299. [CrossRef]

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Manjon, M. J., Merino, A., & Cairns, I. (2024). Bridging Disconnections: Narratives of Collective Social Entrepreneurs on the Energy Poverty Network. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, ahead-of-print, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M. J., Su, R., & Yonish, L. (2025). A Review of Artificial Intelligence, Algorithms, and Robots Through the Lens of Stakeholder Theory. Journal of Management, OnlineFirst. [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, F., Yasin, I. M., Latiff, A. R. A., & Mannan, M. (2023). Exploring the Impact of Bonding, Bridging and Linking Social Capital on Scaling Social Impact: An Emerging Economy Perspective. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, ahead-of-print, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, N. S., Kekwaletswe, R. M., & Seaba, T. R. (2025). Organisational change: Use of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and information systems success model to explain the use of the E-Government service change management framework. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 17, 100171. [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. [CrossRef]

- Naudé, W. (2010). Entrepreneurship, developing countries, and development economics: New approaches and insights. Small Business Economics, 34(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Onomakpo, H. E. O. (2025a). ESG Risk Ratings and Stock Performance in Electric Vehicle Manufacturing: A Panel Regression Analysis Using the Fama-French Five-Factor Model. Journal of Investment Banking and Finance, 3(1), 01-13. [CrossRef]

- Onomakpo, H. E. O. (2025b). Innovation Pathways: Value Capture through Collaboration in Norway. Journal of Investment Banking and Finance, 3(1), XX-XX. http://doi.org/10.33140/JIBF.03.01.11.

- Onomakpo, H. E. O. (2025c). Tech-Driven Circularity: Agile and Lean Synergies. Scientific Research Journal of Ecology and Environmental Protection. Retrieved from https://isrdo.org/journal/SRJEEP/currentissue/tech-driven-circularity-agile-and-lean-synergies.

- Piryatinska, A., & Darkhovsky, B. (2021). Retrospective Change-Points Detection for Multidimensional Time Series of Arbitrary Nature: Model-Free Technology Based on the ϵ-Complexity Theory. Entropy, 23(12), 1626. [CrossRef]

- Popkova, E. G., & Sergi, B. S. (2020). Human capital and AI in industry 4.0. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21(4), 565–581. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M. U., & Guild, P. D. (2022). Stakeholder engagement strategy of technology firms. Technovation, 116, 102497. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

- Xiao, Y. (2025). Pathways to scaling up in emerging economies: A configurational analysis of organizational capabilities in social enterprises. Journal of Business Research, 189, 115091. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).