1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally [

1]. Thermal ablation is currently an established treatment modality for patients with HCC [

2]. In recent years, the detection of tumours small enough to be treated with thermal ablation has increased [

3,

4]; conversely, the outcomes of thermal ablation for liver tumours have improved, particularly when performed percutaneously [

5]. Imaging guidance serves as the cornerstone of every percutaneous intervention, which has also benefitted from significant technological advancements. Ultrasound (US) is widely regarded as the preferred imaging modality for the ablation of hepatic tumours due to its broad availability and the critical advantage of real-time imaging [

6]. However, US can be limited by deep lesions, large patients, or poor tumoral sonographic conspicuity. Furthermore, the livers of patients with HCC are often affected by chronic changes, resulting in diffuse parenchymal inhomogeneity and pseudo-lesion formation [

7].

To overcome these challenges, interventional radiologists can take advantage of advanced US guidance modalities, including contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and ultrasound fusion imaging (USFI). Fusion imaging involves registering two or more imaging datasets from different modalities, whether obtained simultaneously or at different times. When applied to US in interventional radiology, it typically refers to the overlay of pre-procedural cross-sectional studies onto real-time ultrasound images, achievable manually or automatically using anatomical landmarks, pathological landmarks, or sensor coils [

5]. USFI is performed to combine the clear visualization of anatomy and targets offered by cross-sectional imaging with the benefits of real-time ultrasound guidance.

The existing literature, coming mainly from the Eastern world, has demonstrated the utility of US fusion imaging in treating patients with HCC [

8,

9,

10]. In particular, US fusion imaging appears to enhance the operator’s confidence in planning and performing procedures, thus facilitating the treatment of invisible or poorly detectable lesions on simple B-mode US [

11].

Despite the existing evidence, this technique is still not widely adopted, and reports from the Western world are still a minority.

In this study we aim to report the real-life experience with the use of US Fusion imaging for percutaneous thermal ablation of HCC tumors poorly or non-identifiable with simple US.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population Characteristics

This multi-centric retrospective study, in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration, enrolled patients with HCC treated with percutaneous MWA guided by USFI at Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda - Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (n=42) and Ospedale MultiMedica San Giuseppe (n=14), both located in Milan, from January 2021 to December 2024.

All patients included in the study met the following inclusioncriteria:

Age ≥ 18 years;

Solitary HCC measuring ≤ 3.5 cm or ≤ 3 HCC lesions each measuring ≤ 3.0 cm;

Availability of follow-up imaging ≥ 1-month post-ablation.

Availability of pre-procedural imaging performed within 1 month before procedure.

≥ 1 poorly visible or non-visible HCC nodule with B-mode US that was treated with USFI.

Patients in whom the microwave antenna was positioned or corrected with guidance modalities other than USFI were excluded. In cases of multifocal disease, the presence of a single poorly visible or non-visible HCC nodule resulted in the treatment of all remaining nodules with USFI-guided MWA.

Eligibility for tumour ablation was determined, following major societies guidelines [

12,

13], based on standard criteria such as disease stage, comorbidity, patient age, and refusal of surgical intervention.

A multidisciplinary team involving hepatologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and radiation oncologists indicated treatment for each patient.

In our institutions, each patient eligible for percutaneous liver thermal ablation undergoes a pre-procedural outpatient US examination to establish whether the target lesion is visible, poorly visible, or non-visible under simple B-mode. Nodules are classified as poorly visible when they are partially visible even during deep inspiration, or if they exhibit poor conspicuity or have indistinct tumour margins. If no focal change in the sonographic properties of the liver is detected, tumours are classified as non-visible [

14].

Electronic medical records were reviewed to collect epidemiological and patient-related data, including sex, age at the time of treatment, presence of cirrhosis, etiology of liver disease, Child-Pugh score, BCLC stage, and previous hepatic treatments.

Pre-procedural CECT and CEMR were evaluated to assess tumor-related data, including the number of nodules, maximum axial dimension, hepatic segmental location, and challenging localization.

Nodules were classified as challenging when located near potentially delicate structures, specifically within 5 mm of the heart, diaphragm, gallbladder, main bile duct, vessels >3 mm in diameter, or the hepatic capsule.

In patients with multifocal tumors all nodules were treated in the same session.

Procedure

Risks and benefits of the proposed treatment were discussed with each patient before the procedure, and informed consent was obtained.

Coagulation tests were within the normal range for all patients; patients undergoing anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet therapy were managed as specified by interventional society documents. [

15]

Each patient received antibiotic prophylaxis.

All procedures were performed in an angiographic suite with anesthesiologic support and with continuous monitoring of vital parameters by one of six interventional radiologists that had no experience with USFI at the beginning the study period.

Before the procedure, pre-procedural CECT or CEMR images were uploaded into the US machine (Epiq 5, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands).

All patients were positioned supine and kept in light sedation for the first part of the procedure to allow patient cooperation, including breath holding which is required for the fusion process.

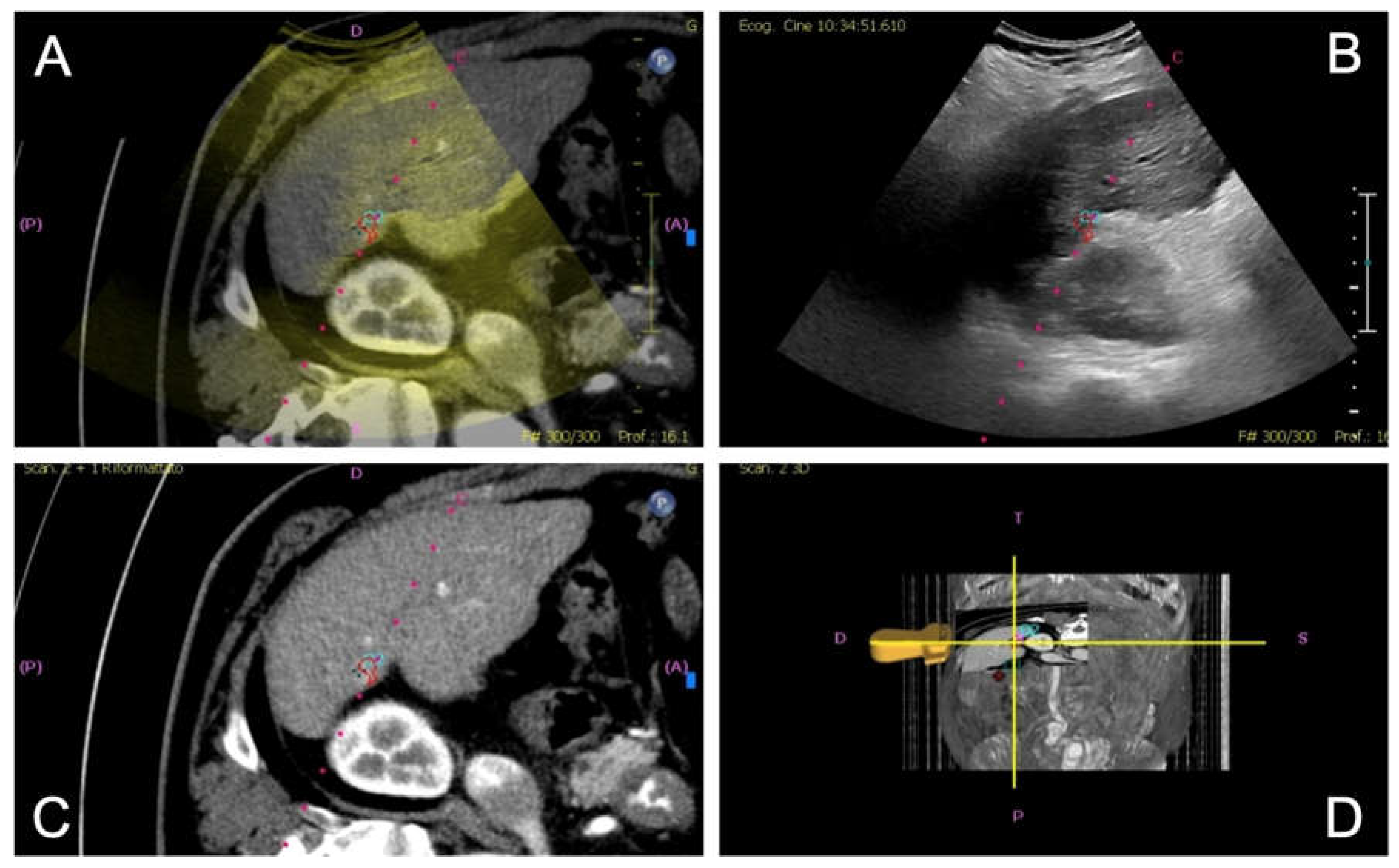

Fusion imaging was performed with electromagnetic tracking using automatic vessel registration via dedicated software (PercuNav System, Philips Medical Systems). The process involves acquiring an ultrasound scan of the liver to create a 3D dataset registered by a software to cross-sectional images based on the hepatic vessels (

Figure 1). If automatic registration was not judged adequate, some manual adjustments were performed.

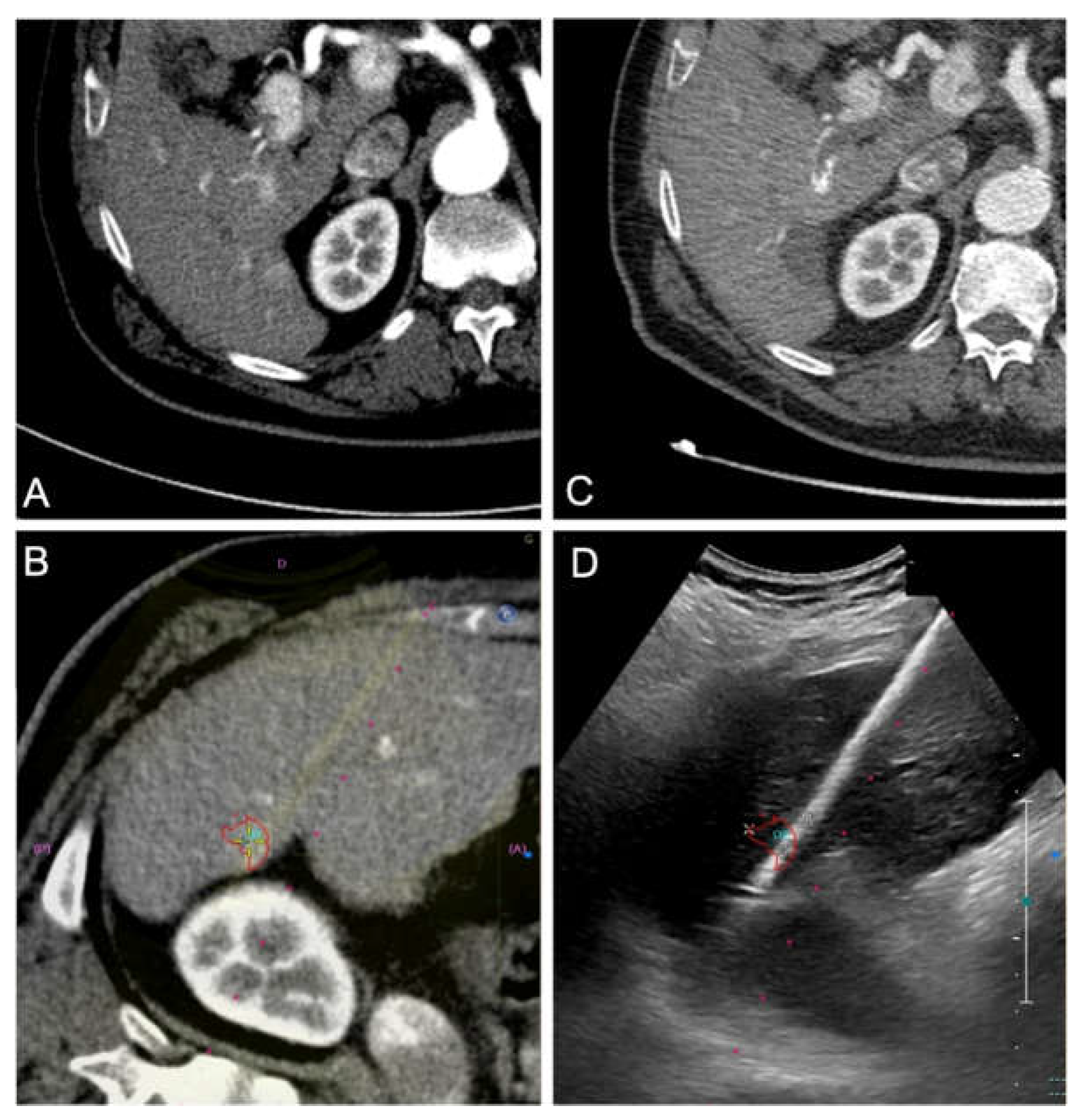

Once the microwave 13.5 G antenna (Emprint Microwave Ablation System, Medtronic, and Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA) was in place, sedation was deepened and ablation was performed with a power of either 100 or 150W for a time established by the operator based on the tumor size and the microwave manufacturer data; all cases were ended with track ablation (

Figure 2c,d).

If the clinical course was uncomplicated, patients were hospitalized for one night after the procedure and discharged the following day.

Technical success was defined as performing the registration process correctly and the entire procedure under USFI guidance.

Any complication during or after procedure was registered [

16].

Figure 1.

Image fusion workflow for percutaneous ablation planning. After co-registration of pre-procedural CT images with real-time ultrasound (US), the integrated display includes: fused CT-US images (A), real-time US alone (B), CT images alone (C), and 3D position of the US probe (D). The target lesion is highlighted with a pink circle, aiding in precise localization for intervention.

Figure 1.

Image fusion workflow for percutaneous ablation planning. After co-registration of pre-procedural CT images with real-time ultrasound (US), the integrated display includes: fused CT-US images (A), real-time US alone (B), CT images alone (C), and 3D position of the US probe (D). The target lesion is highlighted with a pink circle, aiding in precise localization for intervention.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) in the arterial phase demonstrates a newly diagnosed HCC located in segment VI of the liver, near the hepatic capsule. The lesion shows intense arterial-phase hyperenhancement (wash-in), a typical imaging hallmark of HCC. (A) CT-US fusion image following co-registration, enabling precise visualization of the lesion (highlighted by a red target. (B) The corresponding real-time US image during the ablation procedure, with the lesion and ablation needle clearly visualized. (C) One-month follow-up CECT shows no residual enhancement, consistent with complete response to treatment. (D).

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) in the arterial phase demonstrates a newly diagnosed HCC located in segment VI of the liver, near the hepatic capsule. The lesion shows intense arterial-phase hyperenhancement (wash-in), a typical imaging hallmark of HCC. (A) CT-US fusion image following co-registration, enabling precise visualization of the lesion (highlighted by a red target. (B) The corresponding real-time US image during the ablation procedure, with the lesion and ablation needle clearly visualized. (C) One-month follow-up CECT shows no residual enhancement, consistent with complete response to treatment. (D).

Follow-Up and Outcome

Each patient underwent radiological follow-up contrast-enhanced CT after 1 month and every 3-4 months thereafter.

The primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate the outcome of the procedure through local tumor control, measured as residual disease (RD) or local tumor progression (LTP).

RD was the presence of residual viable tumor at the ablative margin at the first 1-month follow-up imaging, whereas LTP was tumor reappearing after ≥ 1 contrast-enhanced follow-up had shown no residual viable tumor at the ablative margin [

17,

18]. Follow-up time was defined as the time interval between the treatment date and the most recent imaging examination at our institution or institutional visit in which imaging from elsewhere was assessed.

In the case of tumor detection during follow-up, the indication for a new treatment was discussed in a multidisciplinary setting.

Patients were censored in case of liver transplant, systemic therapy or death [

19].

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were reported as mean and median values, with corresponding minimum and maximum values, while categorical variables were presented as absolute counts and percentages.

To assess the statistical association between nodule visibility and response at the 1-month follow-up, the single visible nodule present in the dataset was excluded from the analysis.

The associations between local response at 1-month and nodule visibility were evaluated using the Pearson Chi-Square test. Another association test was used to assess local response at 1-month and difficult site location of the nodule.

The same statistical approach was applied to assess the associations between the total follow-up local response and nodule US visibility, and between total follow-up local response and difficult tumor site, after excluding those patients that had residual disease at the first follow-up examination.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (version 29.0.2.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

Population

Between January 2021 and December 2024, a total of 549 patients underwent percutaneous MWA for HCC nodules in the two institutions. Ultrasound fusion imaging (USFI) was used in 56/549 patients (9.8%), 42 from Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda - Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico and 14 from Ospedale MultiMedica San Giuseppe, with a total of 73 nodules; this population was enrolled in our study.

The mean age of included patients was 70.5 years (range 39-91 years). Most patients (96.4%) had liver cirrhosis with the most common etiology of liver disease being HCV, accounting for 51.8% of cases, followed by alcoholic cirrhosis (19.4%) and HBV or HBV/HDV coinfection (19.4%). Most patients were classified as Child-Turcotte-Pugh A (83.9%) and BCLC A (78.6%). The other causes of cirrhosis, along with the Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification and the BCLC groups, are listed in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristic.

Table 1.

Patient characteristic.

| Age |

Mean/Median |

| 70.46/69.5 (39-91) |

| Sex |

Male |

| 44 (78.6%) |

| Female |

| 12 (21.4%) |

| Cirrhosis |

Yes |

| 54 (96.4%) |

| No |

| 2 (3.6%) |

| Etiology |

HCV |

| 29 (51.8%) |

| NAFLD |

| 17 (30.4%) |

| Alcohol |

| 11 (19.6%) |

| HBV and HBV/HDV |

| 11 (19.6%) |

| Child-Pugh |

A |

| 47 (83.9%) |

| B |

| 6 (10.7%) |

| C |

| 1 (1.8%) |

| Not classified |

| 2 (3.6%) |

| BCLC grade |

0 |

| 5 (8.9%) |

| A |

| 44 (78.6%) |

| B |

| 6 (10.7%) |

| C |

| 1 (1.8%) |

Tumor related data are summarized in

Table 2.

Most patients (75%) had monofocal disease, whereas a minority had 2 (19.6%) or 3 (5.4%) HCC nodules. The mean diameter of tumors was 15.5 mm (range 7-33 mm). The VIII segment was the most frequently involved (42,5%).

Among target nodules, 37% had already been subject to treatment attempts and therefore were residual disease. HCC nodules were visible and poorly visible in 43.8% and 54.8% of cases, respectively. A single nodule that was visible on B-mode US was treated with USFI in one patient that had concurrent non-visible tumors.

More than half of the nodules (53.4%) were in challenging areas, particularly near the liver capsule (31.5% of cases). A thermal ablation power of 100 W was applied to 74% of the nodules, while 26% were treated with a thermal ablation power of 150 W.

Table 2.

HCC characteristics among patients included in the study.

Table 2.

HCC characteristics among patients included in the study.

| Number of HCC-nodule |

1 |

| 42 (75%) |

| 2 |

| 11 (19.6%) |

| 3 |

| 3 (5.4%) |

| Previous treatment on target nodule |

Yes |

| 27 (37%) |

| No |

| 46 (63%) |

| Nodule dimension (mm) |

Mean/Median |

| 15.5/15 (5-33) |

| Nodule dimension (n) |

<10 mm |

| 6 (8.2%) |

| 10-20 mm |

| 50 (68.5%) |

| >20mm |

| 17 (23.3%) |

| Hepatic segments |

8 |

| 31 (42.5%) |

| 6 |

| 13 (17.8%) |

| 4 |

| 9 (12.3%) |

| 5 |

| 6 (8.2%) |

| 7 |

| 6 (8.2%) |

| 2 |

| 5 (6.8%) |

| 3 |

| 3 (4.1%) |

| 1 |

| 0 (0%) |

| Difficult location |

Yes |

|

| 39 (53.4%) |

|

| Subcapsular |

| 23 (31.5%) |

| Diaphragm |

| 6 (8.2%) |

| Diaphragm and subcapsular |

| 4 (5.5%) |

| Vessel and subcapsular |

| 4 (5.5%) |

| Vessel |

| 2 (2.7%) |

| No |

| 34 (46.6%) |

| US visibility |

Not Visible |

| 32 (43.8%) |

| Poorly Visible |

| 40 (54.8%) |

| Visible |

| 1 (1.4%) |

Complication and Follow-Up

The follow-up period varied from 1 to 40 months, with a mean of 14.2 months and a median of 13 months.

There were no ablation-related deaths. Most patients (87.5%) did not experience any complications and only one patient experienced major complications. The most common complication following ablation was pain, which affected 4 patients. Fever and post-ablation syndrome were registered in two cases. There was only one case which involved a hemorrhagic complication characterized by hemoperitoneum without evidence of active arterial bleeding, which was monitored in the following days and resolved spontaneously without any intervention.

At 1 month follow-up we registered a complete response in 78.1% of cases while residual disease was observed in 21.9%.

During the entire follow-up time, complete local response was registered in 67.1% and LTP in 9.6% of patients. Mean time to local tumour progression was 12.1 months (range 3–33 months). (

Table 3)

Table 3.

Outcome.

| Local Ablation Response (1 month) |

CR |

| 57 (78.1%) |

| RD |

| 16 (21.9%) |

| Local Ablation Response |

CR |

| 49 (67.1%) |

| LTP |

| 7 (9.6%) |

| RD & Censored Cases |

| 17 (23.3%) |

| Time of LTP (Month) |

Mean/Median |

| 12.1/9 (3-33) |

Table 4 reports the association results between nodule US visibility and local tumor response, both at 1 month and during total follow-up period.

At 1-month poorly visible nodules showed a higher residual disease rate compared to non-visible ones (18.1% vs. 4.2%; p = 0.019), while during the total follow-up time LTP rates were lower for poorly visible nodules when compared to non-visible ones (1.4% vs. 8.3%; p = 0.010).

Table 4.

association between US visibility and local treatment response.

Table 4.

association between US visibility and local treatment response.

| |

US Visibility |

|

| Not Visible Nodules |

Poorly Visible |

|

P-Value |

| Local Ablation Response (1 month) |

RD |

3 (4.2%) |

13 (18.1%) |

|

0.019 |

| CR |

29 (40.3%) |

27 (37.5%) |

|

| |

|

| Local Ablation Response |

LTP |

6 (8.3%) |

1 (1.4%) |

0.010 |

| CR |

23 (31.9%) |

26 (36.1%) |

|

Table 5 reports the association results between nodule location and local tumor response, both at 1 month and during total follow-up period. The location of tumors was not associated to local treatment response both at 1-month and at the total follow-up evaluation.

Table 5.

Association between nodules location and local treatment response.

Table 5.

Association between nodules location and local treatment response.

| |

Difficult Location |

|

| Yes |

No |

|

P-Value |

| Local Ablation Response (1 month) |

RD |

9 (12.3%) |

7 (9.6%) |

|

0.798 |

| CR |

30 (41.1%) |

27 (37.0%) |

|

| |

|

| Local Ablation Response |

LTP |

4 (5.5%) |

3 (4.1%) |

0.839 |

| CR |

25 (34.2%) |

24 (32.9%) |

|

4. Discussion

Imaging guidance represents a key to success in interventional radiology. Percutaneous ablation of HCC is now a standard procedure performed in many cases under B-mode guidance, but this imaging modality has inherent limitations in its ability to correctly visualize some of the target nodules.

To overcome this issue, advanced ultrasound guidance modalities are available today, including USFI [

20,

21].

In this study we reported the real-life clinical use, safety and efficacy of percutaneous thermal ablation of liver HCC from two different Italian centres using USFI as imaging guidance.

This technique is used for a minority of patients with HCC in which indication is given to treatment with percutaneous image-guided thermal ablation; this selected population, composed in our practice by patients with tumors either poorly visible or non-visible with standard US, represents less than 10% of the patients treated (9.8%).

Of note, tumors treated with percutaneous thermal ablation under USFI received previous treatments in a high proportion (37%); this might be expected as an altered anatomy from prior treatments makes nodule identification more difficult or impossible in some cases with standard US, and at the same time highlights the difficulty in treating these lesions.

Interestingly, like in our population, tumors in the eighth segment were the most frequently treated using USFI, likely due to its relative sonographic inaccessibility caused by distance from the ultrasound probe and limited acoustic windows.

Another important point is that a high proportion of tumors treated with USFI were non-visible at all with standard US (43%); for these tumors, excluding MR guidance which is expensive, needs specialized equipment and personnel and therefore is of very limited actual use across the world, USFI guidance is very important to offer ablation as a treatment instead of leaving only the option to convert to TACE.

Keeping this in mind, we observed a complete local response to treatment at 1 month in 78.1% of tumors, which is slightly lower than what described in a recent systematic review by Calandri et al that reported 1-month complete local response rates between 84.3% and 100% [

22]. This may be attributed to several technical and clinical factors. Firstly, in our institution ablations are performed under light/deep sedation to extend the indication to patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia, a factor that makes the registration process more challenging and leads to a variability in the registration of images during the breathing phase. Secondly, the populations examined across studies are different: in our study as mentioned above there was a high rate (43%) of nodules classified as not visible, 37% of patients had previously undergone locoregional treatments and a high number of patients had advanced stage of chronic liver disease. All these factors reflect the challenging population treated with USFI in our referral centre. Additionally, unlike most studies where patients underwent supplemental ablation in case of residual disease therefore resulting in secondary efficacy, in this study we have considered the efficacy of only the first ablation treatment session (primary efficacy).

Interestingly, we registered a high 1-month complete local response rate (95.8%) when considering only the subgroup of non-visible target tumors by simple B-mode US. This is similar to what was reported by Ahn et al., that, among 216 patients with 245 HCCs, described a 1-month complete local response rate of 96.1% for non-visible tumors, which resulted similar to the 97.6% complete local response rate reported for visible nodules [

14].

Regarding LTP rate during the entire follow-up time, our registered rate was 9,6% which is consistent with data reported in literature [

22].

Regarding the association with local treatment response at 1-month and nodule visibility, the fact that poorly visible nodules had a higher rate of residual disease when compared to totally non-visible nodules (18.1% vs 4.2%, respectively p = 0.019) was unexpected, but it might be explained: since the treatment of non-visible nodules relies totally on USFI the operators probably have chased in this group the highest possible degree of accuracy in the coregistration of CT/MR and US images; in contrast, the “poorly visible” group probably suffered from operator bias and overconfidence in the US B-mode, resulting in less accuracy during the registration process and therefore worse outcome [

23]. However, the statistical significance of this data is certainly limited by the low number of patients.

When interpreting the difference observed for LTP rates based on nodule visibility, it has to be kept in mind that the analysis is made only in patients that had an initial complete response, both for poorly visible and non-visible nodule group, and this further limits the significance of results as numbers are even smaller. Nevertheless, in this case a higher rate of LTP during follow-up for non-visible tumors when compared to poorly visible ones (8.3% vs. 1.4%, p = 0.010), is not unexpected.

There was no difference in this study regarding ablation outcomes between tumors in difficult and non-difficult locations, both in terms of residual disease at 1month (12.3% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.798) and LTP during follow-up (5.5% vs. 4.1%, p = 0.839), suggesting that anatomical challenges did not compromise the efficacy of treatment and that USFI may be applied to all cases.

Lastly, in our experience percutaneous MWA ablation of HCC guided by USFI was safe and well tolerated, as demonstrated by the vast majority (87.5%) of cases showing no complications, with only one major complication and no deaths.

This study has several limitations including the limited number of patients, its retrospective nature and the absence of data regarding the quality of the coregistration of CT/MR images to US images for each patient.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in real-life clinical practice USFI-guided percutaneous thermal ablation of liver HCCs is a safe treatment which is used as an advanced tool for complex cases, allowing to offer ablation to otherwise unablatable tumors with satisfactory outcome results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B., L.G.M. and G.C.; methodology, P.B.; software, F.C.; validation, P.B. and G.V.D.A.; formal analysis, F.C.; investigation, F.C.; resources, P.B., V.A., S.A.A., C.L., F.U.I., P.T., A.M.I, L.G.M. and G.C.; data curation, F.C., J.T., N.F., F.U.I. and G.V.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., F.C., G.V.D.A. and V.A.; writing—review and editing, P.B. and G.V.D.A.; visualization, P.B., F.C. and G.V.D.A.; supervision, P.B.; project administration, P.B., G.V.D.A., A.M.I. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the retrospective nature of work.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CECT |

Contrast enhanced computed tomography |

| CEMR |

Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance |

| CR |

Complete response |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| HCC |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C virus |

| HDV |

Hepatitis D virus |

| NAFLD |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| LTP |

Local tumor progression |

| MR |

Magnetic resonance |

| MWA |

Microwave ablation |

| RD |

Residual disease |

| TACE |

Transarterial chemoembolization |

| US |

Ultrasound |

| USFI |

Ultrasound fusion imaging |

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011, 61, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanci C, Sobhani F, Ucbilek E, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Diagnosis and Monitoring of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Liver Transplantation: A Comprehensive Review. Ann Transplant 2016, 21, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park HJ, Lee JM, Park S Bin, et al. Comparison of Knowledge-based Iterative Model Reconstruction and Hybrid Reconstruction Techniques for Liver CT Evaluation of Hypervascular Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2016, 40, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puijk RS, Dijkstra M, van den Bemd BAT, et al. Improved Outcomes of Thermal Ablation for Colorectal Liver Metastases: A 10-Year Analysis from the Prospective Amsterdam CORE Registry (AmCORE). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2022, 45, 1074–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata V, Grassi R, Fusco R, et al. Diagnostic evaluation and ablation treatments assessment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Infect Agent Cancer 2021, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, MW. Fusion imaging of real-time ultrasonography with CT or MRI for hepatic intervention. Ultrasonography 2014, 33, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krücker J, Xu S, Venkatesan A, et al. Clinical Utility of Real-time Fusion Guidance for Biopsy and Ablation. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2011, 22, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng Y, Sun X, Sun H, et al. Fusion imaging versus ultrasound-guided percutaneous thermal ablation of liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Acta radiol 2023, 64, 2506–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami Y, Kudo M. Ultrasound fusion imaging technologies for guidance in ablation therapy for liver cancer. Journal of Medical Ultrasonics 2020, 47, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee MW, Rhim H, Ik Cha D, et al. Planning US for Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation of Small Hepatocellular Carcinomas (1–3 cm): Value of Fusion Imaging with Conventional US and CT/MR Images. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2013, 24, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetti L, de Baére T, Pereira PL, Tarantino FP. CIRSE Standards of Practice on Thermal Ablation of Liver Tumours. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2020, 43, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn SJ, Lee JM, Lee DH, et al. Real-time US-CT/MR fusion imaging for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017, 66, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel IJ, Rahim S, Davidson JC, et al. Society of Interventional Radiology Consensus Guidelines for the Periprocedural Management of Thrombotic and Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Image-Guided Interventions—Part II: Recommendations. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2019, 30, 1168–1184.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippiadis DK, Binkert C, Pellerin O, et al. Cirse Quality Assurance Document and Standards for Classification of Complications: The Cirse Classification System. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017, 40, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puijk RS, Ahmed M, Adam A, et al. Consensus Guidelines for the Definition of Time-to-Event End Points in Image-guided Tumor Ablation: Results of the SIO and DATECAN Initiative. Radiology 2021, 301, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni R, Llovet J. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) Assessment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30, 052–060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, et al. Image-guided Tumor Ablation: Standardization of Terminology and Reporting Criteria—A 10-Year Update. Radiology 2014, 273, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunishi Y, Numata K, Morimoto M, et al. Efficacy of Fusion Imaging Combining Sonography and Hepatobiliary Phase MRI With Gd-EOB-DTPA to Detect Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma. American Journal of Roentgenology 2012, 198, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo PC, Jang H-J, Burns PN, et al. Integration of Contrast-enhanced US into a Multimodality Approach to Imaging of Nodules in a Cirrhotic Liver: How I Do It. Radiology 2017, 282, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calandri M, Mauri G, Yevich S, et al. Fusion Imaging and Virtual Navigation to Guide Percutaneous Thermal Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review of the Literature. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2019, 42, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn SJ, Lee JM, Lee DH, et al. Real-time US-CT/MR fusion imaging for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017, 66, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long Y, Xu E, Zeng Q, et al. Intra-procedural real-time ultrasound fusion imaging improves the therapeutic effect and safety of liver tumor ablation in difficult cases. Am J Cancer Res 2020, 10, 2174–2184. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).