Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

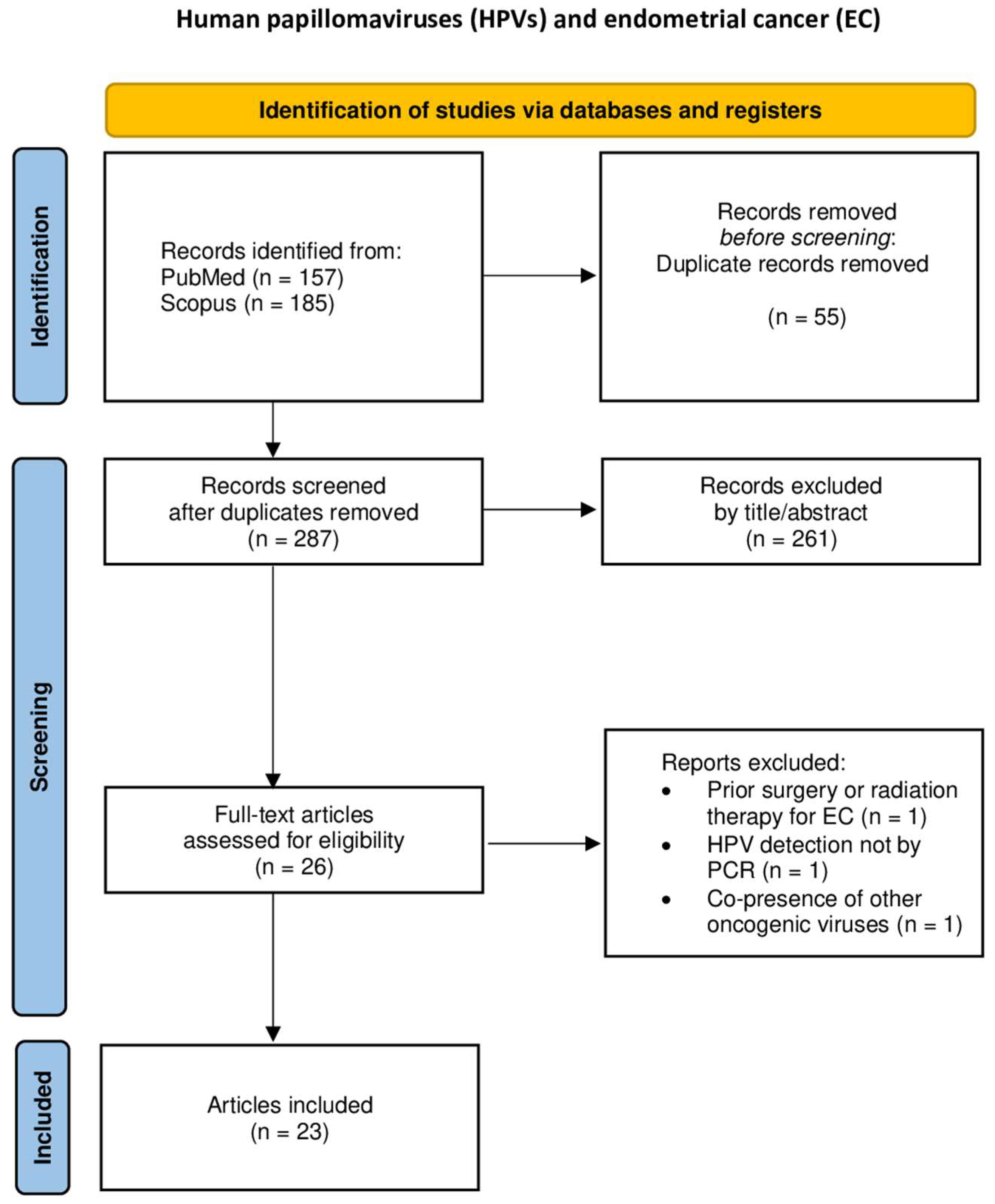

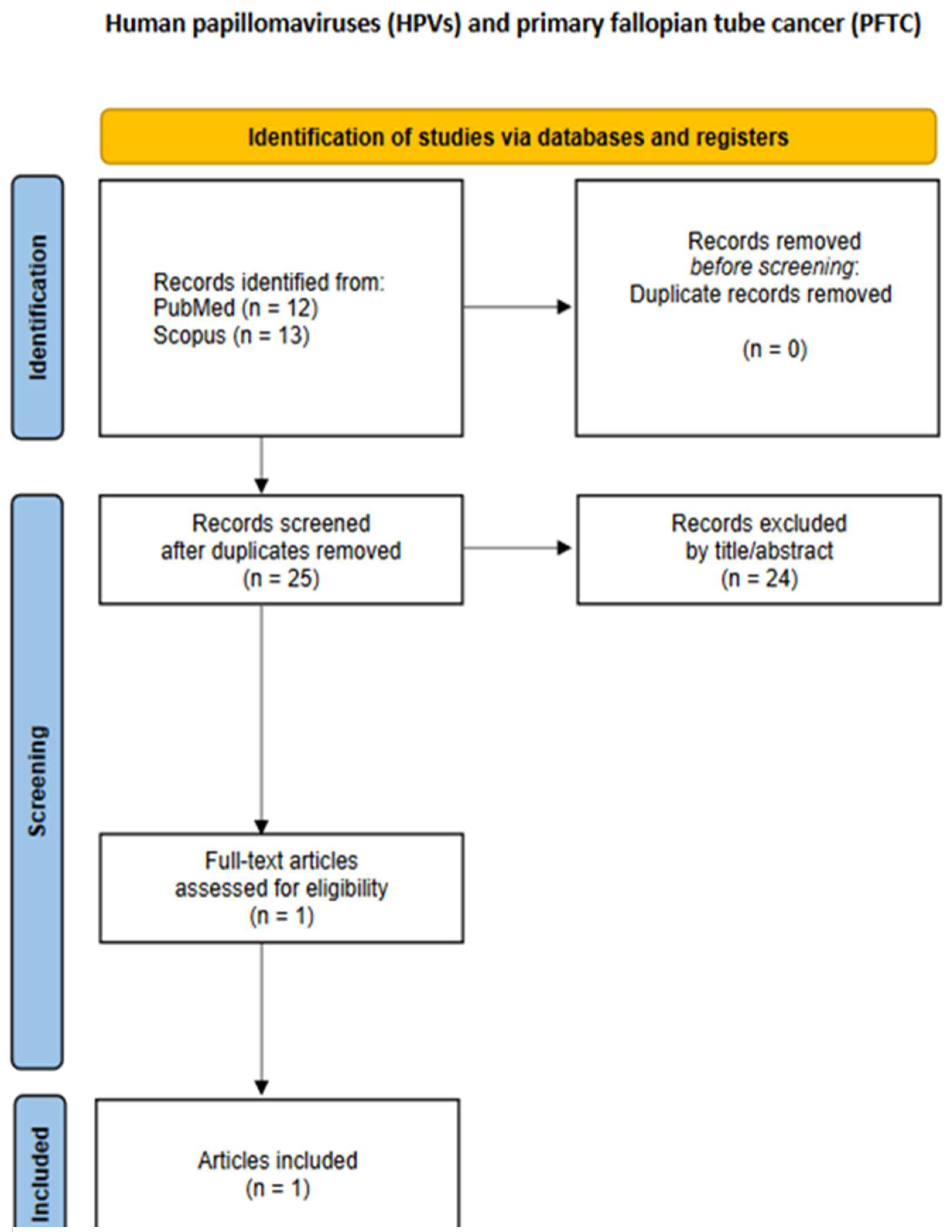

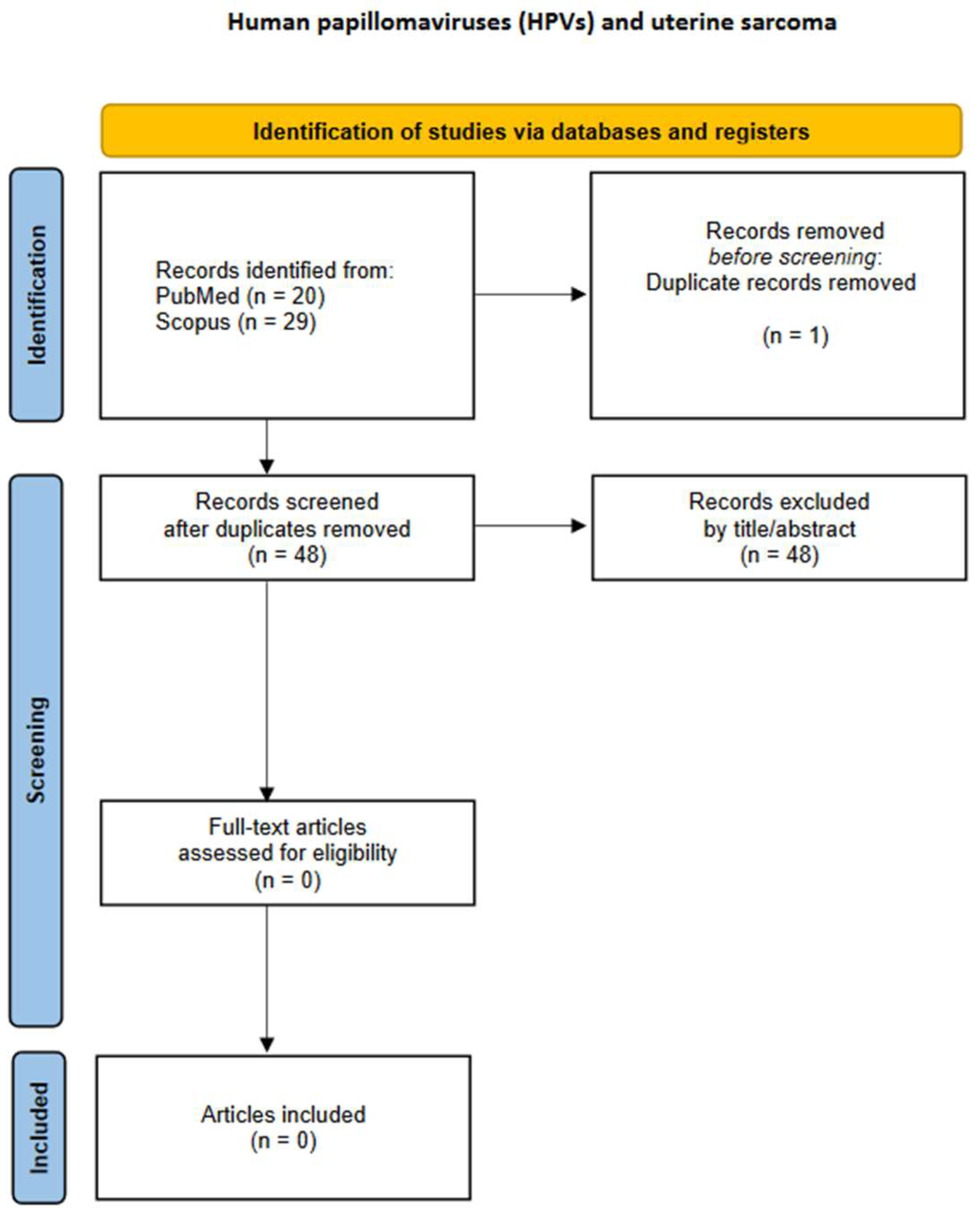

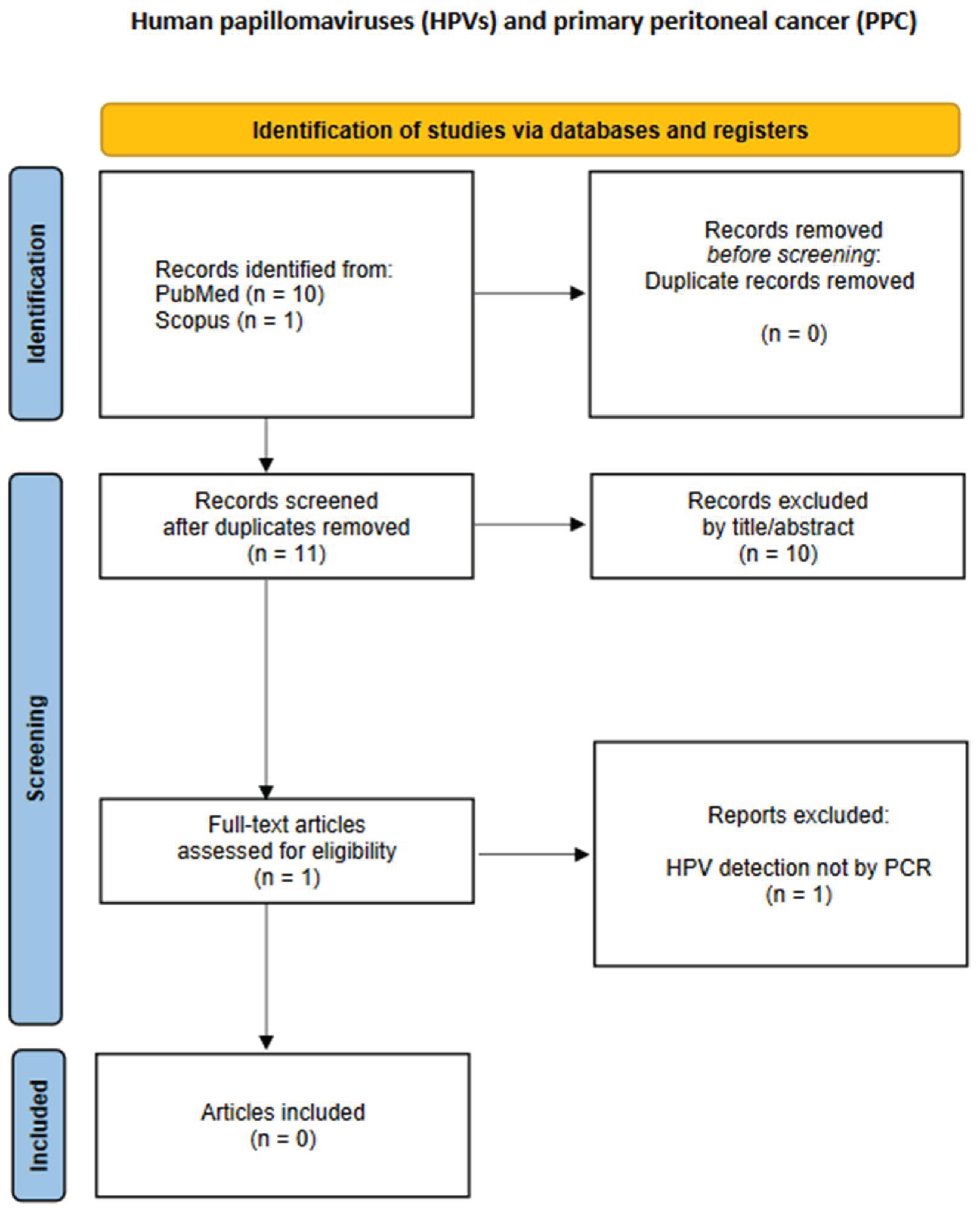

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Screening and Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Endometrial Cancer (EC)

3.2. Uterine Sarcomas

3.3. Primary Fallopian Tube Cancer (PFTC)

3.4. Ovarian Cancer (OC)

3.5. Primary Peritoneal Cancer (PPC)

4. Discussion

4.1. General Considerations

4.2. HPV and Endometrial Cancer

4.3. HPV and Ovarian Cancer

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Practice and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EC | Endometrial Cancer |

| FAS | Fatty Acid Synthase |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded |

| GBM | Glioblastoma Multiforme |

| GLOBOCAN | Global Cancer Observatory |

| GST | Glutathione S-Transferase |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| MDM2 | Mouse Double Minute 2 homolog |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| OC | Ovarian Cancer |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PFTC | Primary Fallopian Tube Carcinoma |

| PPC | Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| TZ | Transformation Zone |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Patel, S.K.; Valicherla, G.R.; Micklo, A.C.; Rohan, L.C. Drug Delivery Strategies for Management of Women’s Health Issues in the Upper Genital Tract. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 177, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatla, N.; Aoki, D.; Sharma, D.N.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the Cervix Uteri: 2021 Update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2021, 155, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskas, M.; Amant, F.; Mirza, M.R.; Creutzberg, C.L. Cancer of the Corpus Uteri: 2021 Update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2021, 155, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatani, N.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Prat, J. Uterine Sarcomas. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2018, 143, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Renz, M.; Kehoe, S.; Kumar, L.; Friedlander, M. Cancer of the Ovary, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneum: 2021 Update. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2021, 155, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.M.; Laversanne, M.; Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Parkin, D.M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. The GLOBOCAN 2022 Cancer Estimates: Data Sources, Methods, and a Snapshot of the Cancer Burden Worldwide. Int J Cancer 2025, 156, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walboomers, J.M.; Jacobs, M. V; Manos, M.M.; Bosch, F.X.; Kummer, J.A.; Shah, K. V; Snijders, P.J.; Peto, J.; Meijer, C.J.; Muñoz, N. Human Papillomavirus Is a Necessary Cause of Invasive Cervical Cancer Worldwide. J Pathol 1999, 189, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses in Human Cancers. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1999, 111, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachira, D.; Congedo, M.T.; D’Argento, E.; Meacci, E.; Evangelista, J.; Sassorossi, C.; Calabrese, G.; Nocera, A.; Kuzmych, K.; Santangelo, R.; et al. The Role of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) in Primary Lung Cancer Development: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Life 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyouni, A.A.A. Human Papillomavirus in Cancer: Infection, Disease Transmission, and Progress in Vaccines. J Infect Public Health 2023, 16, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingerslev, K.; Hogdall, E.; Skovrider-Ruminski, W.; Schnack, T.H.; Karlsen, M.A.; Nedergaard, L.; Hogdall, C.; Blaakær, J. High-Risk HPV Is Not Associated with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer in a Caucasian Population. Infect Agent Cancer 2016, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisseljova, N.; Zhordania, K.; Fedorova, M.; Katargin, A.; Valeeva, A.; Pajanidi, J.; Pavlova, L.; Khvan, O.; Vinokurova, S. Detection of Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Ovarian Cancer by Different Test Systems. Intervirology 2020, 62, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, D.; Schmoeckel, E.; Höhn, A.K.; Hiller, G.G.R.; Horn, L.-C. Aktuelle WHO-Klassifikation Des Weiblichen Genitale. Pathologe 2021, 42, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Glasziou, P.; Mar, C. Del; Bannach-Brown, A.; Stehlik, P.; Scott, A.M. A Full Systematic Review Was Completed in 2 Weeks Using Automation Tools: A Case Study. J Clin Epidemiol 2020, 121, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Lubad, M.A.; Jarajreh, D.A.; Helaly, G.F.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Haddadin, W.J.; Dabobash, M.D.; Albataineh, E.M.; Aqel, A.A.; Alnawaiseh, N.A. Human Papillomavirus as an Independent Risk Factor of Invasive Cervical and Endometrial Carcinomas in Jordan. J Infect Public Health 2020, 13, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, E.N.; Villa, L.L.; De Souza, I. V; Sebastião, A.P.M.; Urbanetz, A.A.; De Carvalho, N.S. Does Human Papillomavirus Play a Role in Endometrial Carcinogenesis? International Journal of Gynecological Pathology 2009, 28, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadayi, N.; Gecer, M.; Kayahan, S.; Yamuc, E.; Onak, N.K.; Korkmaz, T.; Yavuzer, D. Association between Human Papillomavirus and Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. Med Oncol 2013, 30, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, M.; Brestovac, B.; Thompson, J.; Sterrett, G.; Filion, P.; Smith, D.; Frost, F. The Value of HPV DNA Typing in the Distinction between Adenocarcinoma of Endocervical and Endometrial Origin. Pathology 2003, 35, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, G.; Sharifi, N.; Sadeghian, A.; Rezaei, A.; Shidaee, H. Failure to Demonstrate the Role of High Risk Human Papilloma Virus in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. 2012.

- Dadashi, M.; Eslami, G.; Faghihloo, E.; Pourmohammad, A.; Hosseini, J.; Taheripanah, R.; Arab-Mazar, Z. Detection of Human Papilloma Virus Type 16 in Epithelial Ovarian Tumors Samples. Arch Clin Infect Dis 2017, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.H.; Hsueh, S.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, M.Y.; You, G.B.; Chang, H.C.; Pao, C.C. Human Papillomavirus in Benign and Malignant Ovarian and Endometrial Tissues. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1992, 11, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.E.; Abdel Fattah, N.F.; Seadawy, M.G.; Lymona, A.M.; Nasr, S.S.; El Leithy, A.A.; Abdelwahed, F.M.; Nassar, A. The Clinical Importance of IFN-γ and Human Epididymis Protein 4 in Egyptian Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Combined with HPV Infection. Hum Immunol 2024, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, K.; Nakakuki, K.; Imai, H.; Shiraishi, T.; Inuzuka, M. Infection of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and P53 over-Expression in Human Female Genital Tract Carcinoma. JOURNAL-PAKISTAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 1996, 46, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, J.J.; Landers, R.J.; Crowley, M.; Healy, I.; O’Donovan, M.; Healy, V.; Kealy, W.F.; Hogan, J.; Doyle, C.T. Human Papillomavirus and Mixed Epithelial Tumors of the Endometrium. Hum Pathol 1998, 29, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Malpica, A.; Deavers, M.T.; Guo, M.; Villa, L.L.; Nuovo, G.; Merino, M.J.; Silva, E.G. Endometrial Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Corpus Involving the Cervix: Some Cases Probably Represent Independent Primaries. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology 2010, 29, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bures, N.; Nelson, G.; Duan, Q.; Magliocco, A.; Demetrick, D.; Duggan, M.A. Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Endometrium: Clinicopathologic and Molecular Characteristics. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2013, 32, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Shroyer, K.R.; Markham, N.E.; Inoue, M.; Iwamoto, S.; Kyo, S.; Enomoto, T. Association of Human Papillomavirus with Malignant and Premalignant Lesions of the Uterine Endometrium. Hum Pathol 1995, 26, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachisuga, T.; Matsuo, N.; Iwasaka, T.; Sugimori, H.; Tsuneyoshi, M. Human Papilloma Virus and P53 Overexpression in Carcinomas of the Uterine Cervix, Lower Uterine Segment and Endometrium. Pathology 1996, 28, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.; D’Adda, T.; Gnetti, L.; Froio, E.; Merisio, C.; Melpignano, M. Detection of Human Papillomavirus in Organs of Upper Genital Tract in Women with Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2006, 16, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hording, U.; Daugaard, S.; Visfeldt, J. Adenocarcinoma of the Cervix and Adenocarcinoma of the Endometrium: Distinction with PCR-Mediated Detection of HPV DNA. APMIS 1997, 105, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, S.M.; Wong, L.C.; Xu, C.M.; Cheung, A.N.Y.; Tsang, P.C.K.; Ngan, H.Y.S. Detection of Human Papillomavirus DNA in Malignant Lesions from Chinese Women with Carcinomas of the Upper Genital Tract. Gynecol Oncol 2002, 87, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Pao, C.C. Detection of Human Papillomavirus RNA in Ovarian and Endometrial Carcinomas by Reverse Transcription/Polymerase Chain Reaction. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1994, 38, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Enríquez, A.; González-Rocha, T.; Burgos, E.; Stolnicu, S.; Mendiola, M.; Nogales, F.F.; Hardisson, D. Transitional Cell Carcinoma of the Endometrium and Endometrial Carcinoma with Transitional Cell Differentiation: A Clinicopathologic Study of 5 Cases and Review of the Literature. Hum Pathol 2008, 39, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.-W.; Zivanovic, O.; Theuerkauf, I.; Dürkop, B.; Hernando, J.J.; Simon, M.; Büttner, R.; Kuhn, W. The Diagnostic Utility of Human Papillomavirus-Testing in Combination with Immunohistochemistry in Advanced Gynaecologic Pelvic Tumours: A New Diagnostic Approach. Int J Oncol 2004, 24, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J.; Liu, V.W.S.; Tsang, P.C.K.; Yip, A.M.W.; Ng, T.-Y.; Cheung, A.N.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S. Comparison of Human Papillomavirus DNA Levels in Gynecological Cancers: Implication for Cancer Development. Tumour Biol 2003, 24, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, G.D.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Rozendaal, L.; Daalmeijer, N.F.; Risse, E.K.J.; Voorhorst, F.J.; Jiwa, N.M.; van der Linden, H.C.; de Schipper, F.A.; Runsink, A.P.; et al. The Presence of High-Risk HPV Combined with Specific P53 and P16INK4a Expression Patterns Points to High-Risk HPV as the Main Causative Agent for Adenocarcinoma in Situ and Adenocarcinoma of the Cervix. J Pathol 2003, 201, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, W.R.; Monk, B.J.; Burger, R.A.; Bergen, S.; Wilczynski, S.P. Does Human Papillomavirus Have a Role in Cancers of the Uterine Corpus? Gynecol Oncol 1999, 75, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnebaum, I.B.; Köhler, T.; Stickeler, E.; Rosenthal, H.E.; Kieback, D.G.; Kreienberg, R. P53 Mutation Is Associated with High S-Phase Fraction in Primary Fallopian Tube Adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 1996, 74, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffa, M.; Koumantakis, E.; Ergazaki, M.; Malamou-Mitsi, V.; Spandidos, D.A. Detection of Ras Gene Mutations and HPV in Lesions of the Human Female Reproductive Tract. Int J Oncol 1994, 5, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnebaum, I.B.; Maier, S.; Tong, X.W.; Rosenthal, H.E.; Mobus, V.J.; Kieback, D.G.; Kreienberg, R. Human Papillomavirus Integration Is Not Associated with Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer in German Patients. Cancer Epidemiology-Biomarkers and Prevention 1995, 4, 573–576. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.R.; Chan, P.J.; Seraj, I.M.; King, A. Absence of Human Papillomavirus E6-E7 Transforming Genes from HPV 16 and 18 in Malignant Ovarian Carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1999, 72, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.K.; Hafez, M.M.; Kamel, M.M.; Zekri, A.R.N. Human Papillomavirus Genotypes and Methylation of CADM1, PAX1, MAL and ADCYAP1 Genes in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2017, 18, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; You, Q.; Yao, G.; Geng, J.; Ma, R.; Meng, H. Evaluation of P16 in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer for a 10-Year Study in Northeast China: Significance of Hpv in Correlation with Pd-L1 Expression. Cancer Manag Res 2020, 12, 6747–6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarych, D.; Mikulski, D.; Wilczyński, M.; Wilczyński, J.R.; Kania, K.D.; Haręża, D.; Malinowski, A.; Perdas, E.; Nowak, M.; Paradowska, E. Differential MicroRNA Expression Analysis in Patients with HPV-Infected Ovarian Neoplasms. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.S.; Wong, Y.F.; Tam, O.S.; Tam, J.S. Detection of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Infection in Paraffin-Embedded Tissues of Endometrial Carcinoma. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1993, 33, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.; D’Adda, T.; Merisio, C.; Gnetti, L. Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Endometrium: A Case Report with Immunohistochemical and Molecular Study. Gynecol Oncol 2005, 96, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, A.; Nishida, T.; Okina, H.; Tomioka, Y.; Hirai, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Yakushiji, M. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Endometrium with Human Papillomavirus Type 31. Kurume Med J 1997, 44, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, A.; Nishida, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Hori, K.; Honda, S.; Yakushiji, M. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Endometrium with Human Papillomavirus Type 31 and without Tumor Suppressor Gene P53 Mutation. Gynecol Oncol 1997, 65, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatalica, Z.; Foster, J.M.; Loggie, B.W. Low Grade Peritoneal Mucinous Carcinomatosis Associated with Human Papilloma Virus Infection: Case Report. Croat Med J 2008, 49, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svahn, M.F.; Faber, M.T.; Christensen, J.; Norrild, B.; Kjaer, S.K. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Tissue. A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014, 93, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, T.B.; Svahn, M.F.; Faber, M.T.; Duun-Henriksen, A.K.; Junge, J.; Norrild, B.; Kjaer, S.K. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2014, 134, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, M.I.; Silva, G.D.; De Azedo Simões, P.W.T.; Souza, M. V; Panatto, A.P.R.; Simon, C.S.; Madeira, K.; Medeiros, L.R. The Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Ovarian Cancer : A Systematic Review. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2013, 23, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimova, M.K.; Kokorina, E. V; Tsyganov, M.M.; Churuksaeva, O.N.; Litviakov, N. V Human Papillomavirus and Ovarian Cancer (Review of Literature and Meta-Analysis). Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, S.; Amine, A.; Thies, S.; Taube, E.T.; Braicu, E.I.; Sehouli, J.; Kaufmann, A.M. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Detection in Ovarian Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2021, 40, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verguts, J.; Amant, F.; Moerman, P.; Vergote, I. HPV Induced Ovarian Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007, 276, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, O.; Miriam Elfström, K.; Lamin, H.; Dillner, J. HPV-MRNA and HPV-DNA Detection in Samples Taken up to Seven Years before Severe Dysplasia of Cervix Uteri. Int J Cancer 2019, 144, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Malignancy site | PubMed | SCOPUS |

|---|---|---|

| Endometrial cancer | (("human papillomavirus viruses"[MeSH Terms] OR "human papillomavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "HPV"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("endometrial neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR "endometrial neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR ("endometrial"[All Fields] AND "neoplasms"[MeSH Terms]) OR "endometrial cancer*"[Title/Abstract] OR "endometrial carcinoma*"[Title/Abstract] OR ("endometrial"[All Fields] AND "malignant neoplasm*"[Title/Abstract]) OR "endometrial ca"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((excludepreprints[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (1985/1/1:2025/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])) | (INDEXTERMS("human papillomavirus viruses") OR TITLE-ABS("human papillomavirus") OR TITLE-ABS(HPV)) AND (INDEXTERMS("endometrial neoplasms") OR INDEXTERMS("endometrial neoplasms") OR (ALL(endometrial) AND INDEXTERMS(neoplasms)) OR TITLE-ABS("endometrial cancer*") OR TITLE-ABS("endometrial carcinoma*") OR (ALL(endometrial) AND TITLE-ABS("malignant neoplasm*")) OR TITLE-ABS("endometrial ca")) AND PUBYEAR > 1985 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE,"final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ) ) |

| Uterine sarcoma | (("human papillomavirus viruses"[MeSH Terms] OR "human papillomavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "HPV"[Title/Abstract]) AND ((("uterin"[All Fields] OR "uterines"[All Fields] OR "uterus"[MeSH Terms] OR "uterus"[All Fields] OR "uterine"[All Fields]) AND "sarcoma"[MeSH Terms]) OR "uterine sarcoma*"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((excludepreprints[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (1985/1/1:2025/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])) | (INDEXTERMS("human papillomavirus viruses") OR TITLE-ABS("human papillomavirus") OR TITLE-ABS(HPV)) AND (((ALL(uterin) OR ALL(uterines) OR INDEXTERMS(uterus) OR ALL(uterus) OR ALL(uterine)) AND INDEXTERMS(sarcoma)) OR TITLE-ABS("uterine sarcoma*")) AND PUBYEAR > 1984 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE,"final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ) ) |

| Fallopian tube cancer | (("human papillomavirus viruses"[MeSH Terms] OR "human papillomavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "HPV"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("ovarian neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR "ovarian neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR (("ovarian"[All Fields] OR "ovarians"[All Fields]) AND "neoplasms"[MeSH Terms]) OR "ovarian cancer*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian carcinoma*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian malignant neoplasm*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian ca"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((excludepreprints[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (1985/1/1:2025/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])) | (INDEXTERMS("human papillomavirus viruses") OR TITLE-ABS("human papillomavirus") OR TITLE-ABS(HPV)) AND (INDEXTERMS("fallopian tube neoplasms") OR TITLE-ABS("fallopian tube cancer*") OR TITLE-ABS("fallopian tube carcinoma*") OR ((INDEXTERMS("fallopian tubes") OR (ALL(fallopian) AND ALL(tubes)) OR ALL("fallopian tubes") OR (ALL(fallopian) AND ALL(tube)) OR ALL("fallopian tube")) AND TITLE-ABS("malignant neoplasm*"))) AND PUBYEAR > 1995 AND PUBYEAR < 2022 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE,"final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ) ) |

| Ovarian cancer | (("human papillomavirus viruses"[MeSH Terms] OR "human papillomavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "HPV"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("ovarian neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR "ovarian neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR (("ovarian"[All Fields] OR "ovarians"[All Fields]) AND "neoplasms"[MeSH Terms]) OR "ovarian cancer*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian carcinoma*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian malignant neoplasm*"[Title/Abstract] OR "ovarian ca"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((excludepreprints[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (1985/1/1:2025/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])) | (INDEXTERMS("human papillomavirus viruses") OR TITLE-ABS("human papillomavirus") OR TITLE-ABS(HPV)) AND (INDEXTERMS("ovarian neoplasms") OR INDEXTERMS("ovarian neoplasms") OR ((ALL(ovarian) OR ALL(ovarians)) AND INDEXTERMS(neoplasms)) OR TITLE-ABS("ovarian cancer*") OR TITLE-ABS("ovarian carcinoma*") OR TITLE-ABS("ovarian malignant neoplasm*") OR TITLE-ABS("ovarian ca")) AND PUBYEAR > 1986 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE,"final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ) ) |

| Primary peritoneal cancer | (("human papillomavirus viruses"[MeSH Terms] OR "human papillomavirus"[Title/Abstract] OR "HPV"[Title/Abstract]) AND ((("primaries"[All Fields] OR "primary"[All Fields]) AND ("peritoneally"[All Fields] OR "peritoneum"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritoneum"[All Fields] OR "peritoneal"[All Fields] OR "peritonism"[All Fields] OR "peritonitis"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritonitis"[All Fields]) AND "neoplasms"[MeSH Terms]) OR (("primaries"[All Fields] OR "primary"[All Fields]) AND ("peritoneally"[All Fields] OR "peritoneum"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritoneum"[All Fields] OR "peritoneal"[All Fields] OR "peritonism"[All Fields] OR "peritonitis"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritonitis"[All Fields]) AND "carcinoma"[MeSH Terms]) OR "primary peritoneal cancer*"[Title/Abstract] OR "primary peritoneal carcinoma*"[Title/Abstract] OR (("primaries"[All Fields] OR "primary"[All Fields]) AND ("peritoneally"[All Fields] OR "peritoneum"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritoneum"[All Fields] OR "peritoneal"[All Fields] OR "peritonism"[All Fields] OR "peritonitis"[MeSH Terms] OR "peritonitis"[All Fields]) AND "malignant neoplasm*"[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((excludepreprints[Filter]) AND (fft[Filter]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (female[Filter]) AND (1985/1/1:2025/1/1[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter])) | (INDEXTERMS("human papillomavirus viruses") OR TITLE-ABS("human papillomavirus") OR TITLE-ABS(HPV)) AND (((ALL(primaries) OR ALL(primary)) AND (ALL(peritoneally) OR INDEXTERMS(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneal) OR ALL(peritonism) OR INDEXTERMS(peritonitis) OR ALL(peritonitis)) AND INDEXTERMS(neoplasms)) OR ((ALL(primaries) OR ALL(primary)) AND (ALL(peritoneally) OR INDEXTERMS(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneal) OR ALL(peritonism) OR INDEXTERMS(peritonitis) OR ALL(peritonitis)) AND INDEXTERMS(carcinoma)) OR TITLE-ABS("primary peritoneal cancer*") OR TITLE-ABS("primary peritoneal carcinoma*") OR ((ALL(primaries) OR ALL(primary)) AND (ALL(peritoneally) OR INDEXTERMS(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneum) OR ALL(peritoneal) OR ALL(peritonism) OR INDEXTERMS(peritonitis) OR ALL(peritonitis)) AND TITLE-ABS("malignant neoplasm*"))) AND PUBYEAR > 1986 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE,"final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ) ) |

| First author, year, reference | Study type | Malignant neoplasm histopathologic type | HPV positivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anwar et al., 1996[24] | Case series | 15 endometrial carcinomas |

|

| 3 ovarian carcinomas | None | ||

| O'Leary et al., 1998[25] | Case series | 20 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 2/20 (10%) HPV-11 |

| 41 endometrial adenocarcinomas with squamous metaplasia |

|

||

| 2 adenosquamous endometrial carcinomas | 1/2 (50%) HPV-6 & HPV-33 (same patient) |

||

| Jiang et al., 2010[26] | Case series | 4 endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas |

|

| Abu-Lubad et al., 2020[16] | Case-control study | 36 endometrial carcinomas | 3/20 (15%) HPV-18 |

| Bures et al., 2013[27] | Case series | 5 primary squamous cell carcinomas of the endometrium8 endometrioid endometrial carcinomas | None |

| Fedrizzi et al., 2009[17] | Case-control study | 50 endometrial carcinomas |

|

| Fujita et al., 1995[28] | Case series | 85 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 8/85 (9%) HPV-16 |

| Giordano et al., 2006[30] | Case series | 2 mucinous microglandular endometrial adenocarcinomas | None |

| Giordano et al., 2005[47] | Case report | 1 primary squamous cell endometrial carcinoma | None |

| Hachisuga et al., 1996[29] | Case series | 30 endometrial carcinomas | None |

| Hording et al., 1997[31] | Case series | 23 endometrial carcinomas | None |

| Ip et al., 2002[32] | Case series | 55 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 5/55 (9%) HPV-16 |

| 60 primary epithelial ovarian carcinomas | 6/60 (10%) HPV-16/18 | ||

| 4 mucinous borderline ovarian tumors | 3/60 (5%) HPV-16 1/60 (2%) HPV-18 |

||

| 1 clear cell ovarian adenocarcinoma | 1/60 (2%) HPV-16 | ||

| 1 mucinous ovarian adenocarcinoma | 1/60 (2%) HPV-16 | ||

| Karadayi et al., 2013[18] | Case-control study | 30 endometrial adenocarcinomas | None |

| Kataoka et al., 1997[49] | Case report | 1 primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium | 1 (100%) HPV-31 |

| Lai et al., 1994[33] | Case series | 18 epithelial ovarian adenocarcinomas, of which: 9 serous 7 mucinous 2 undifferentiated adenocarcinomas |

9/18 (50%) HPV-16 3/18 (17%) HPV-18 |

| 18 endometrial adenocarcinomas, of which: 10 adenocarcinomas 6 adenosquamous carcinomas 1 clear cell carcinoma 1 undifferentiated carcinoma |

8/18 (44%) HPV-16 3/18 (17%) HPV-18 |

||

| Mariño-Enríquez et al., 2008[34] | Case series | 5 primary transitional cell carcinomas of the endometrium and endometrial carcinomas with transitional cell differentiation | None |

| Park et al., 2004[35] | Case series | 10 endometrial adenocarcinomas | None |

| Plunkett et al., 2003[19] | Case-control study | 50 endometrial carcinomas, of which: 38 endometrioid villoglandular 1 serous papillary 7 mixed adenocarcinomas 1 adenosquamous |

1/50 (2%) HPV-16 |

| Yang et al., 2003[36] | Case series | 46 endometrioid endometrial carcinomas | Endometrial carcinomas: 7/46 (15%) HPV-16 |

| 14 endometrioid ovarian carcinomas | |||

| 21 serous ovarian carcinomas | |||

| 11 mucinous ovarian carcinomas | Ovarian carcinomas: 18/56 (32%) HPV-16 1/56 (2%) HPV-18 |

||

| 6 clear cell ovarian carcinomas | |||

| 4 undifferentiated ovarian carcinomas | |||

| Zielinski et al., 2003[37] | Case series | 20 endometrial adenocarcinomas | None |

| Brewster et al., 1999[38] | Case series | 58 endometrioid endometrial carcinomas | None |

| 4 adenosquamous endometrial carcinomas | 1/4 (25%) HPV-16 | ||

| 3 malignant mixed mesodermal tumors of the endometrial cavity | None | ||

| 1 squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrial cavity | 1 (100%) HPV-18 | ||

| Wong et al., 1993[46] | Case series | 22 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 1/22 (5%) HPV-16 |

| Runnebaum et al., 1996[39] | Case series | 7 primary fallopian tube adenocarcinomas | None |

| Koffa et al., 1994[40] | Case series | 14 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 5/14 (36%) HPV-? (11/16/18/33) |

| 1 clear cell endometrial carcinoma | None | ||

| 1 uterine leiomyosarcoma | None | ||

| 5 ovarian adenocarcinomas | None | ||

| 1 ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma | None | ||

| 1 borderline mucinous ovarian tumor | None | ||

| 1 Krukenberg tumor | None | ||

| Runnebaum et al., 1995[41] | Case series | 20 ovarian serous cystadenocarcinomas | None |

| 2 ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas | None | ||

| 2 ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinomas | None | ||

| 1 ovarian mixed (endometrioid and serous) cystadenocarcinoma | None | ||

| 1 heterologous malignant mixed Müllerian ovarian tumor | None | ||

| 1 undifferentiated ovarian carcinoma | None | ||

| 1 granulosa cell ovarian tumor | None | ||

| Chen et al., 1999[42] | Case series | 20 ovarian carcinomas | None |

| Alavi et al., 2012[20] | Case-control study | 43 ovarian serous cystadenocarcinomas | 2/43 (5%) HPV-? (16/18) |

| 7 ovarian mucinous adenocarcinomas | 1/7 (14%) HPV-? (16/18) | ||

| Ingerslev et al., 2016[11] | Case series | 146 ovarian serous adenocarcinomas | 1/146 (1%) HPV-18 |

| 10 ovarian mucinous adenocarcinomas | None | ||

| 12 ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas | None | ||

| 6 ovarian clear cell carcinomas | None | ||

| Dadashi et al., 2017[21] | Case-control study | 25 ovarian carcinomas | 25/70 (36%) HPV-16 |

| Hassan et al., 2017[43] | Case series | 100 ovarian carcinomas | 5/100 (5%) HPV-16 4/100 (4%) HPV-18 1/100 (1%) HPV-33 |

| Kisseljova et al., 2020[12] | Case series | 29 ovarian serous adenocarcinomas | 18/34 (53%) HPV-16 |

| 2 ovarian mucinous adenocarcinomas | |||

| 3 ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas | |||

| Yang et al., 2020[44] | Case series | 310 ovarian carcinomas, of which: 208 serous ovarian adenocarcinomas 48 mucinous ovarian adenocarcinomas |

78/310 (25%) HPV-? |

| Jarych et al., 2024[45] | Case series | 33 serous ovarian adenocarcinomas | 14/46 (30%) HPV-16 9/46 (20%) HPV-18 7/46 (15%) HPV-16+18 |

| 5 borderline ovarian tumors | |||

| 3 clear-cell ovarian adenocarcinomas | |||

| 3 mucinous ovarian adenocarcinomas | |||

| 2 other types of epithelial ovarian adenocarcinomas | |||

| Lai et al., 1992[22] | Case-control study | 11 epithelial ovarian carcinomas, of which: 7 serous ovarian carcinomas 3 mucinous ovarian carcinomas 1 mixed ovarian carcinoma |

2/11 (18%) HPV-16 3/11 (27%) HPV-18 |

| 8 endometrial adenocarcinomas | 2/8 (25%) HPV-16 | ||

| Mohamed et al., 2024[23] | Case-control study | 47 epithelial ovarian carcinomas, of which: 15 high grade serous carcinomas 11 papillary serous adenocarcinomas 10 endometrioid adenocarcinomas 4 undifferentiated carcinomas 2 squamous cell carcinomas 2 mucinous borderline tumors (atypical proliferative mucinous tumors) 2 adult type granulosa cell tumors 1 mixed malignant mullerian tumor |

6/47 (13%) HPV-16 1/47 (2%) HPV-18 5/47 (11%) HPV-? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).