Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What analytical techniques are currently employed to characterize silica dust in MNM mines?

- How does the toxicity of silica dust correlate with the prevalence of lung diseases among MNM mine workers?

- How effective have past regulatory measures been in reducing silica exposure, and what potential impact might the revised MSHA standards have on future occupational health outcomes?

2. The Laws in Effect in Metal and Nonmetal Mines

2.1. A Brief History of Silica Regulations in the United States

2.2. Monitoring and Assessment of Respirable Dust Exposure

2.3. The Permissible Exposure Limits (PEL) for Respirable Crystalline Silica in MNM Mines

- To enforce compliance with the new PEL, MSHA has outlined a standardized procedure for sampling and analyzing respirable dust in MNM mines: Sample Collection and Preparation: Respirable dust sample collection is performed by MSHA inspectors at the mine. They select certain miners and a specific working area for sampling. The task is performed by using gravimetric samplers, which collect air from both the breathing zone of the miners and that of the specific work area selected for the entire shift.

- Quartz Content Analysis: Samples that are damaged, ripped, or appear wet, based on visual inspection, are disposed of. The accepted mine samples are weighed and validated for sufficient mass gain. Samples exceeding the minimum mass threshold are analyzed for RCS. In MNM mines, analysis is conducted using XRD techniques, following protocols such as MSHA P-2, NIOSH 7500, and OSHA ID-142. In contrast, samples from coal mines are analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Silica content in MNM mine samples is measured by comparing the mass of quartz or cristobalite obtained through XRD to the total respirable dust mass. Exposure calculations for MNM and coal miners are based on an 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA) for standard shifts. However, for shifts exceeding eight hours, the calculation methods differ: in coal mines, exposures are assessed based on the actual shift length, whereas in MNM mines, the assessment remains anchored to an 8-hour TWA regardless of shift duration. This procedural distinction reflects the regulatory frameworks established for each sector.. Table 2 compares MSHA procedures for RCS analysis in MNM mines and coal mines [15].

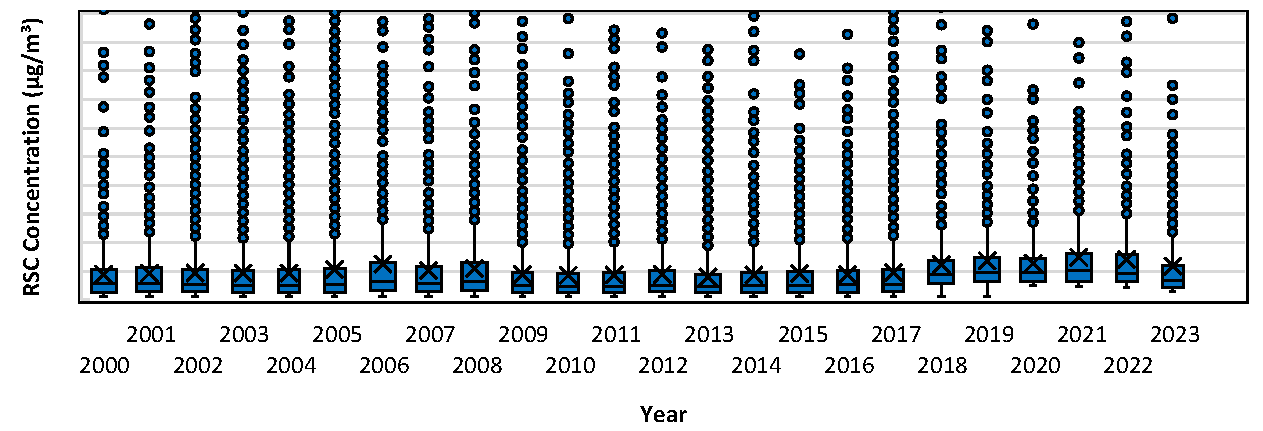

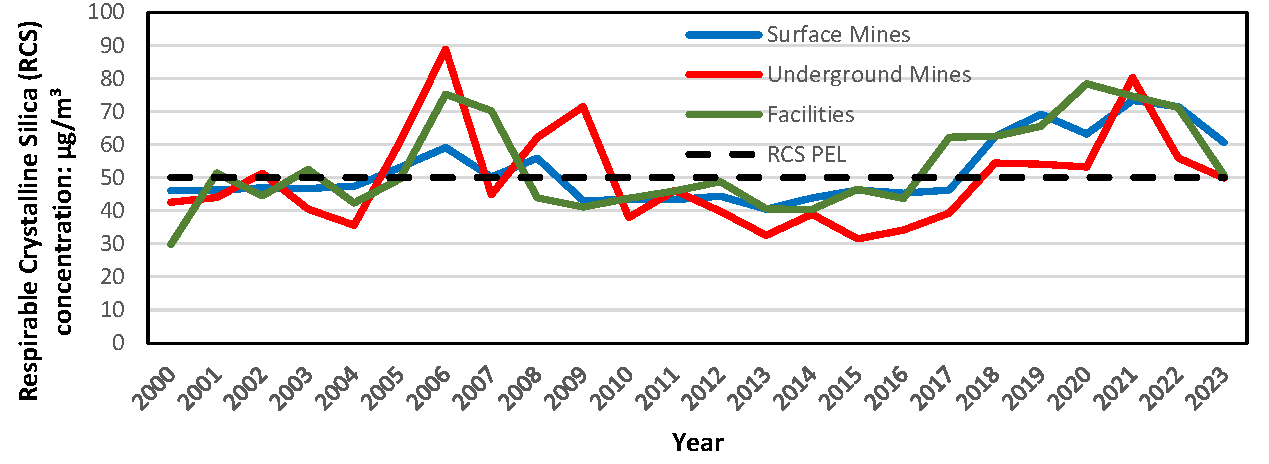

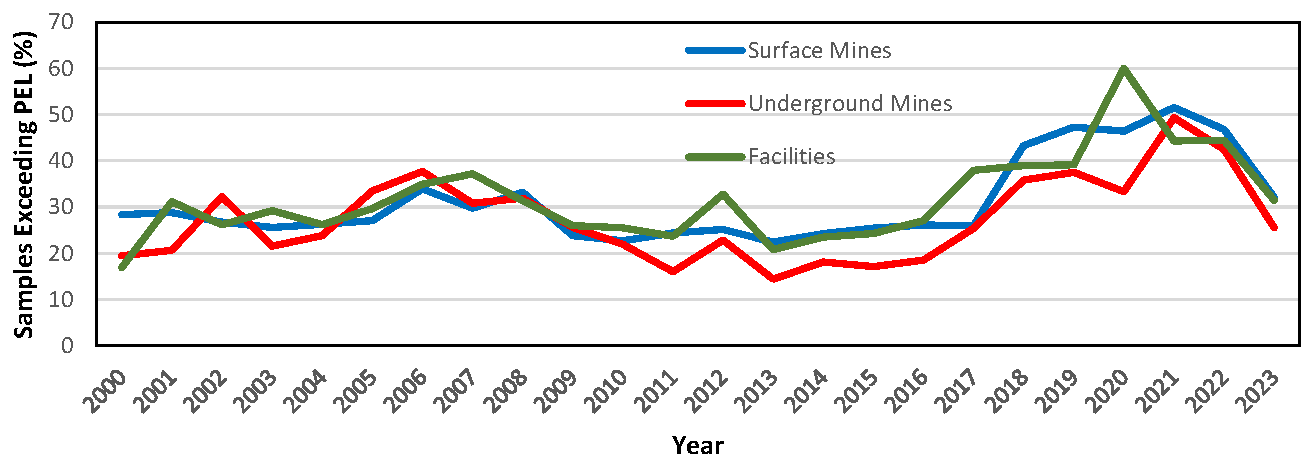

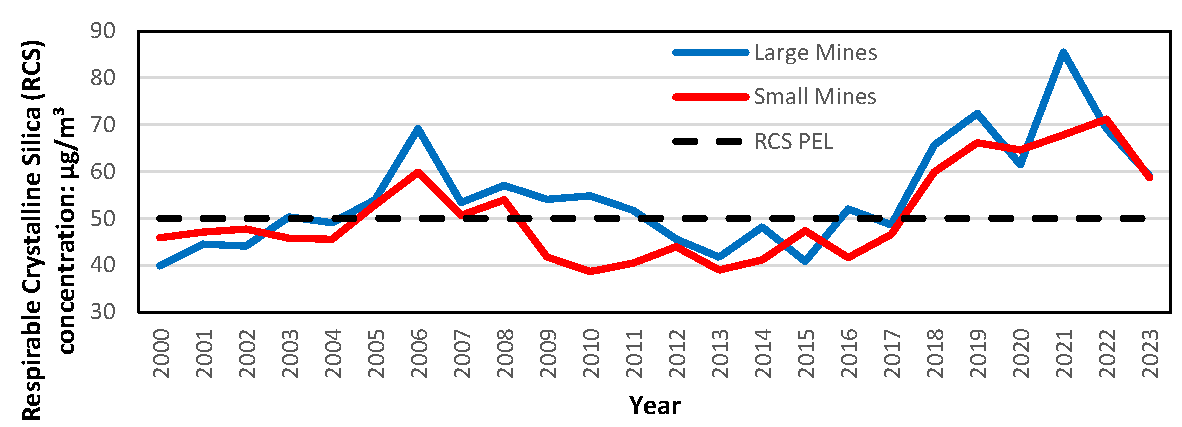

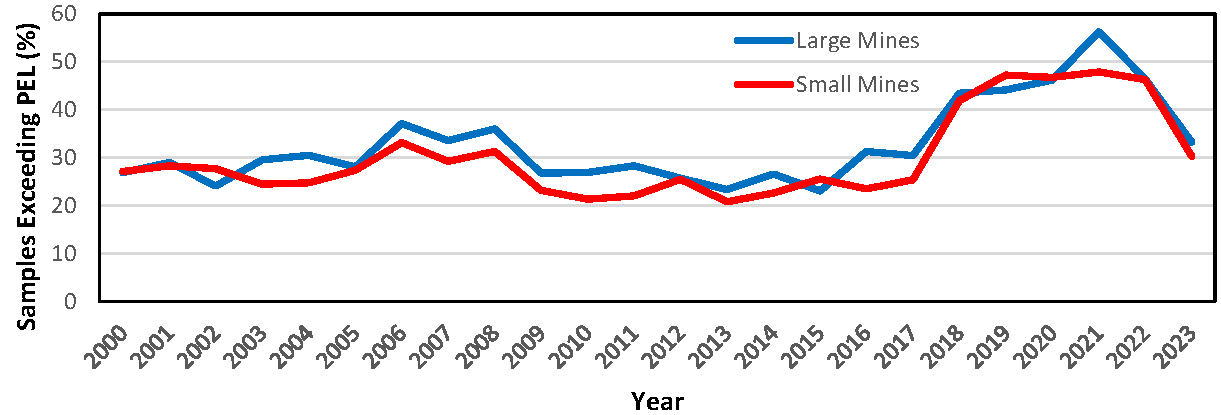

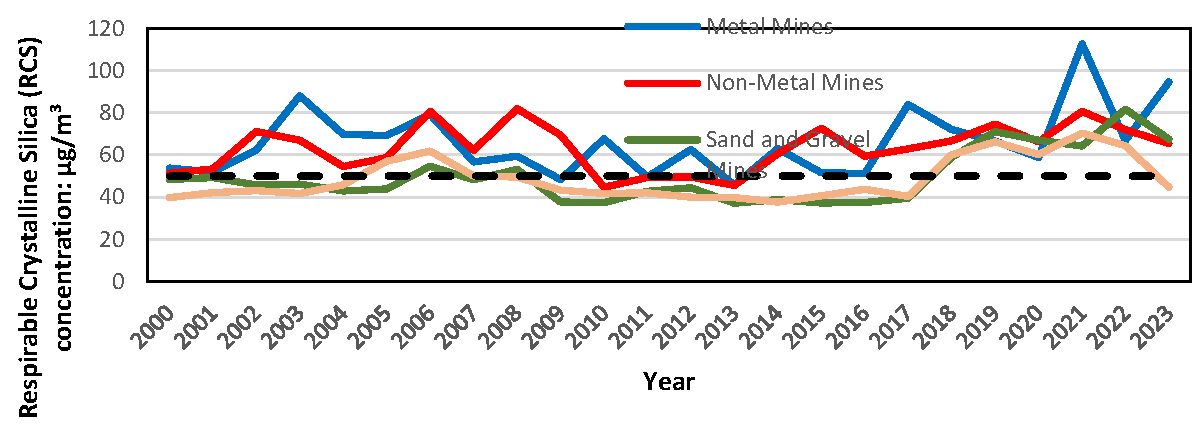

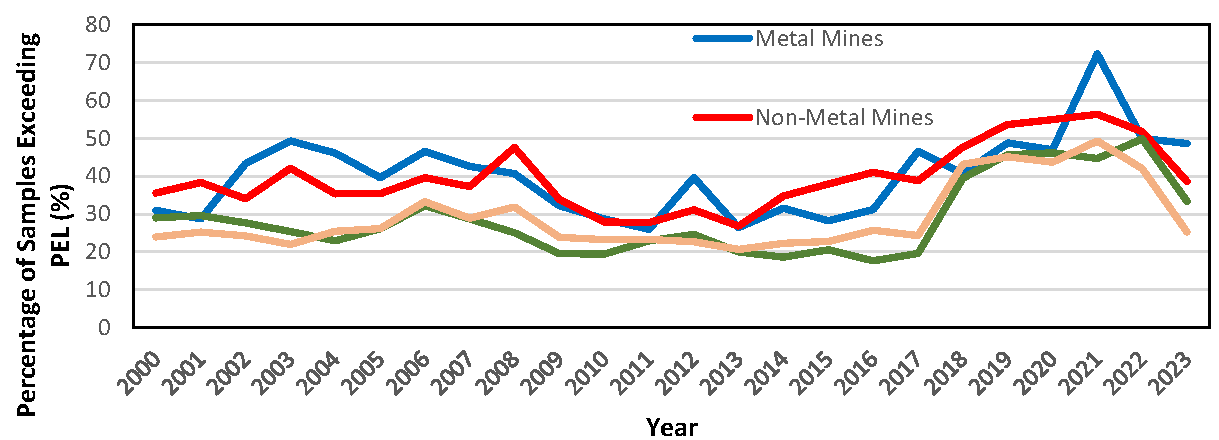

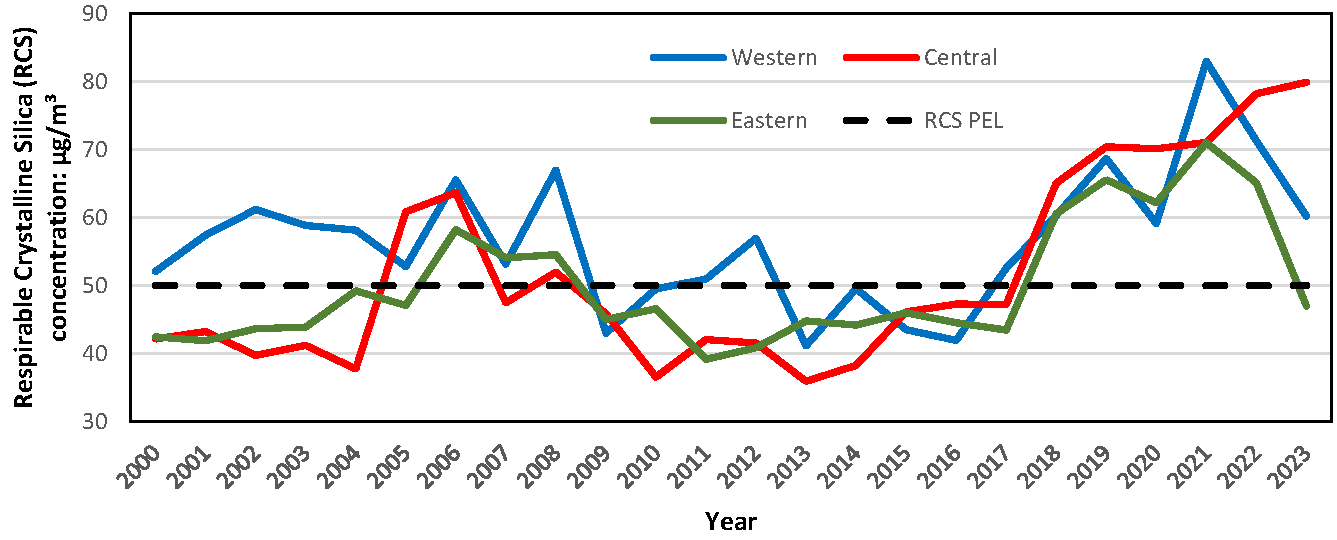

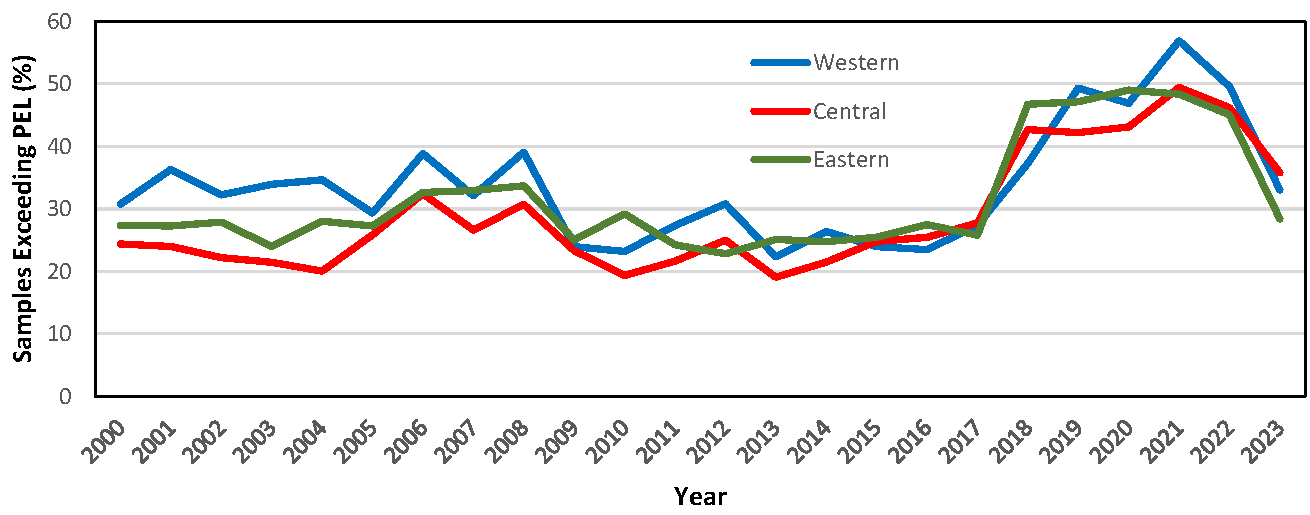

3. Respirable Crystalline Silica Concentrations in U.S. MNM Mines from 2000 to 2023

4. Characterization Techniques in Effect in MNM Mines

- Particle Size Distribution Analysis: Particle size distribution analysis provides insights into the depth and site of particle deposition within the human respiratory tract. Measurements are typically conducted by analyzing particle suspensions and measuring impedance changes as particles pass through an aperture, which generates a signal proportional to the particle volume [30,32,33].

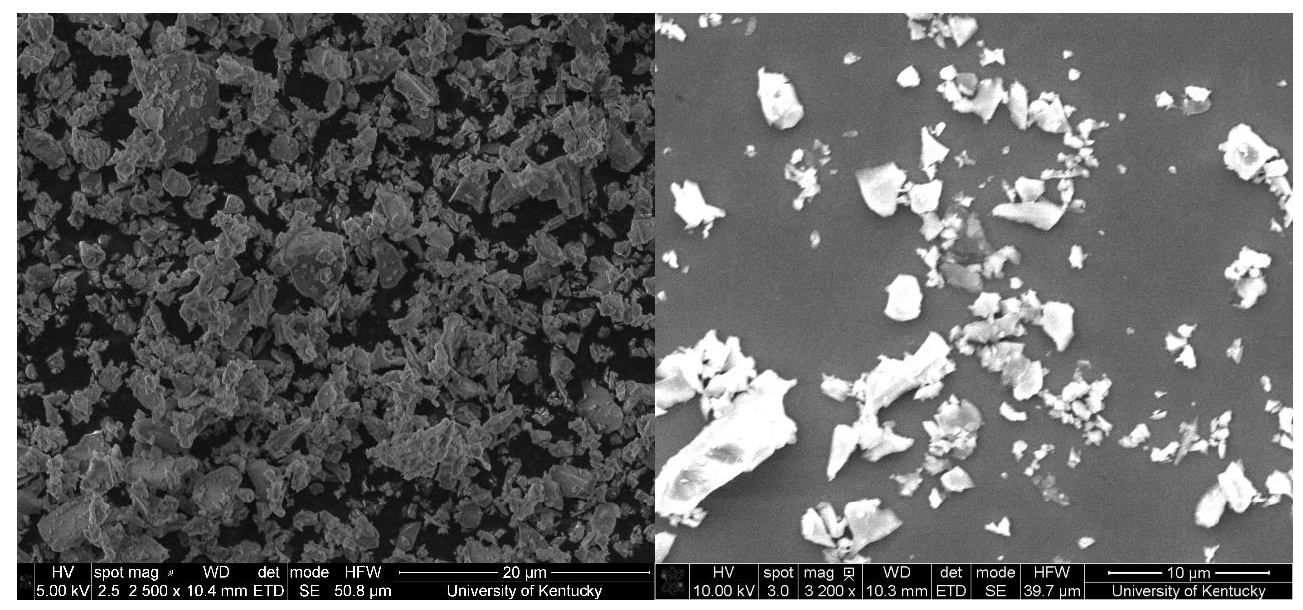

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): SEM offers detailed information on the physical and chemical properties of dust particles, including morphology, size, surface characteristics [34,35,36,37]. Although SEM provides extensive characterization capabilities, it is important to remember that SEM provides less accurate characterization in elements with low atomic masses [30,38].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): TEM enables high-resolution analysis of individual particles, providing detailed information about particle structure and composition. Although phase identification through diffraction patterns is time-consuming, TEM is particularly valuable for selective analysis of submicron particles [30,39].

- Geochemical Assessment: The assessment involves analyzing the elemental composition of dust to identify the presence of metals and metalloids associated with health risks. Such analyses are crucial for understanding environmental contamination and occupational exposure in MNM mining environments [30,39,41].

5. Toxicity of Dust in MNM Mines

6. Results and Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Enhanced Monitoring and Surveillance: Ongoing assessment of dust concentrations, along with systematic health surveillance initiatives, will facilitate the identification of high-risk zones and personnel, allowing for prompt responses.

- Enhanced Dust Control Strategies: The implementation of engineering controls, including ventilation systems, wet drilling, and dust suppression technologies, can markedly decrease dust levels in mining settings.

- Worker Education and Training: Instructing miners on the hazards of respirable crystalline silica (RCS) exposure and the significance of utilizing personal protective equipment (PPE) can mitigate exposure and enhance overall safety.

- Research and Development: Additional investigation is required to enhance comprehension of the health risks associated with RCS exposure, especially the synergistic implications of silica in conjunction with other deleterious compounds, including radon and diesel exhaust. Establishing swift and precise testing methodologies for dust characterization will be essential for efficient risk management.

Funding

References

- Shumate, A.M. , et al., Morbidity and health risk factors among New Mexico miners: a comparison across mining sectors. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utembe, W.; Faustman, E.; Matatiele, P.; Gulumian, M. Hazards identified and the need for health risk assessment in the South African mining industry. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2015, 34, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.A.; Petsonk, E.L.; Rose, C.; Young, B.; Regier, M.; Najmuddin, A.; Abraham, J.L.; Churg, A.; Green, F.H.Y. Lung Pathology in U.S. Coal Workers with Rapidly Progressive Pneumoconiosis Implicates Silica and Silicates. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. , et al., Concentration, sources and health effects of silica in ambient respirable dust of Jharia Coalfields Region, India. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2022. 34, p. 68.

- Poinen-Rughooputh, S.; Rughooputh, M.S.; Guo, Y.; Rong, Y.; Chen, W. Occupational exposure to silica dust and risk of lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.C. T.S. Yu, and W. Chen, Silicosis. The Lancet, 2012. 379, p. 2008-2018.

- Cecala, A.B. , et al., Lower respirable dust and noise exposure with an open structure. 2006.

- Myshchenko, I.; Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska, M.; Dudarewicz, A.; Bortkiewicz, A. Health Risks Due to Co-Exposure to Noise and Respirable Crystalline Silica Among Workers in the Open-Pit Mining Industry—Results of a Preliminary Study. Toxics 2024, 12, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, R.; Akugizibwe, P.; Siegfried, N.; Rees, D. The association between silica exposure, silicosis and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langwana, V.; Khoza, N.; Rathebe, P.C.; Mbonane, T.P.; Masekameni, M.D. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices on Occupation Health and Safety Amongst Mine Workers Exposed to Crystalline Silica Dust in a Low-Income Country: A Case Study from Lesotho. Safety 2024, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierska, D.; Thomassen, L.C.J.; Lison, D.; Martens, J.A.; Hoet, P.H. The nanosilica hazard: another variable entity. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H. , et al., Silica-associated lung disease: an old-world exposure in modern industries. Respirology, 2019. 24, p. 1165-1175.

- Marques Da Silva, V. , et al., Pulmonary toxicity of silica linked to its micro-or nanometric particle size and crystal structure: A review. Nanomaterials, 2022. 12, p. 2392.

- Vupputuri, S.; Parks, C.G.; Nylander-French, L.A.; Owen-Smith, A.; Hogan, S.L.; Sandler, D.P. Occupational Silica Exposure and Chronic Kidney Disease. Ren. Fail. 2012, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSHA, Lowering Miners’ Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica and Improving Respiratory Protection. 2024, Mine Safety and Health Administration. p. 28218-28228.

- Misra, S.; Sussell, A.L.; Wilson, S.E.; Poplin, G.S. Occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica among US metal and nonmetal miners, 2000–2019. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAteer, J.D. , The Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977: Preserving a Law that Works. W. Va. L. Rev., 1995. 98: p. 1105.

- Karmis, M. , Mine health and safety management. 2001: SME.

- Kasongo, J.; Alleman, L.Y.; Kanda, J.-M.; Kaniki, A.; Riffault, V. Metal-bearing airborne particles from mining activities: A review on their characteristics, impacts and research perspectives. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 951, 175426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MANUAL, S. , Measurement of Hazardous Substances. 2023.

- Ali, L. , Analysis of the Efficacy of the Msha Respirable Dust Sampling Program in Surface Metal/Nonmetal Mining Industry. 2017: The Pennsylvania State University.

- Watts Jr, W.F. B. Huynh, and G. Ramachandran, Quartz concentration trends in metal and nonmetal mining. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 2012. 9, p. 720-732.

- Paluchamy, B. P. Mishra, and D.C. Panigrahi, Airborne respirable dust in fully mechanised underground metalliferous mines–Generation, health impacts and control measures for cleaner production. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021. 296: p. 126524.

- Wang, D. , et al., Comparison of risk of silicosis in metal mines and pottery factories: a 44-year cohort study. Chest, 2020. 158, p. 1050-1059.

- Nabiwa, L.; Masekameni; Hayumbu, P. ; Sifanu, M.; Mmereki, D.; Linde, S. A systematic review of respirable dust and respirable crystalline silica dust concentrations in copper mines: guiding Zambia’s development of an airborne dust monitoring programme. Occup. Heal. South. Afr. 2024, 30, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupani, M.P. Challenges and opportunities for silicosis prevention and control: need for a national health program on silicosis in India. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2023, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumchev, K.; Van Hoang, D.; Lee, A. Case Report: Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica and Respiratory Health Among Australian Mine Workers. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 798472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, D.H. and D. Rees, Can the South African milestones for reducing exposure to respirable crystalline silica and silicosis be achieved and reliably monitored? Frontiers in Public Health, 2020. 8: p. 107.

- Okoye, K. and S. Hosseini, Mann–Whitney U Test and Kruskal–Wallis H Test Statistics in R, in R programming: Statistical data analysis in research. 2024, Springer. p. 225-246.

- Noble, T.L. , et al., Mineral dust emissions at metalliferous mine sites. Environ. Indic. Met. Min. 2017, 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ferg, E.E.; Loyson, P.; Gromer, G. The Influence of Particle Size and Composition on the Quantification of Airborne Quartz Analysis on Filter Paper. Ind. Heal. 2008, 46, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, T.L., et al., Prediction of mineral dust properties at mine sites. Environ. Indic. Met. Min. 2017, 343-354.

- McTainsh, G., A. Lynch, and R. Hales, Particle-size analysis of aeolian dusts, soils and sediments in very small quantities using a Coulter Multisizer. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 1997. 22, p. 1207-1216.

- Jones, T.; Blackmore, P.; Leach, M.; Bérubé, K.; Sexton, K.; Richards, R. Characterisation of Airborne Particles Collected Within and Proximal to an Opencast Coalmine: South Wales, U.K. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2002, 75, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.; Jones, T.P.; Beérubeé, K.A.; Wise, H.; Richards, R. Toxicity of airborne dust generated by opencast coal mining. Miner. Mag. 2003, 67, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G. Methods for Characterization of Composition of Fly Ashes from Coal-Fired Power Stations: A Critical Overview. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuccio, G.S.; Schlaegle, S.F.; Lersch, T.L.; Huffman, G.P.; Chen, Y.; Shah, N. Measurement of fine particulate matter using electron microscopy techniques. Fuel Process. Technol. 2004, 85, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choël, M.; Deboudt, K.; Osán, J.; Flament, P.; Van Grieken, R. Quantitative Determination of Low-ZElements in Single Atmospheric Particles on Boron Substrates by Automated Scanning Electron Microscopy−Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 5686–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lottermoser, B. Predictive environmental indicators in metal mining. Environ. Indic. Met. Min. 2017, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Laskina, O.; Young, M.A.; Kleiber, P.D.; Grassian, V.H. Infrared extinction spectroscopy and micro-Raman spectroscopy of select components of mineral dust mixed with organic compounds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 6593–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, S.; Bravo, M.A.; Quiroz, W.; Moreno, T.; Karanasiou, A.; Font, O.; Vidal, V.; Cereceda, F. Distribution of trace elements in particle size fractions for contaminated soils by a copper smelting from different zones of the Puchuncaví Valley (Chile). Chemosphere 2014, 111, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenbach, J. , Classification of PM10 and fall out dust sampling in the iron ore mining industry, Northern Cape province of South Africa. 2019.

- Entwistle, J.A.; Hursthouse, A.S.; Reis, P.A.M.; Stewart, A.G. Metalliferous Mine Dust: Human Health Impacts and the Potential Determinants of Disease in Mining Communities. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2019, 5, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keast, D.; Sheppard, N.P.; Papadimitriou, J. Some biological properties of respirable iron ore dust. Environ. Res. 1987, 42, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenhorst, R. , Characterisation of airborne dust in a South African opencast iron ore mine: a pilot study. 2013.

- Paluchamy, B.; Mishra, D.P. Dust pollution hazard and harmful airborne dust exposure assessment for remote LHD operator in underground lead–zinc ore mine open stope. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 89585–89596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraos, C. , In Vitro Toxicity Assessment of Dust Emissions from Six South African Gold Mine Tailings Sites. 2019, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences.

- Bandopadhyay, A.K. and S. Kumari, Quartz in respirable airborne dust in workplaces in selected coal and metal mines in India, in Silica and Associated Respirable Mineral Particles. 2013, ASTM International.

- Arrandale, V.H.; Kalenge, S.; Demers, P.A. Silica exposure in a mining exploration operation. Arch. Environ. Occup. Heal. 2017, 73, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.F.; Autenrieth, D.A.; Cauda, E.; Chubb, L.; Spear, T.M.; Wock, S.; Rosenthal, S. A comparison of respirable crystalline silica concentration measurements using a direct-on-filter Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) transmission method vs. a traditional laboratory X-ray diffraction method. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2018, 15, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slouka, S.; Brune, J.; Rostami, J.; Tsai, C.; Sidrow, E. Characterization of Respirable Dust Generated from Full Scale Cutting Tests in Limestone with Conical Picks at Three Stages of Wear. Minerals 2022, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, R.; Barone, T.; Cauda, E.; Krebs, P.; Pejcic, B.; Daboss, S.; Mizaikoff, B. Direct infrared spectroscopy for the size-independent identification and quantification of respirable particles relative mass in mine dusts. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 3499–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaggard, H.N. , Mineralogical characterization of tailings and respirable dust from lead-rich mine waste and its control on bioaccessibility. 2012: Queen's University (Canada).

- Kumari, S.; Kumar, R.; Mishra, K.K.; Pandey, J.K.; Udayabhanu, G.N.; Bandopadhyay, A.K. Determination of Quartz and Its Abundance in Respirable Airborne Dust in Both Coal and Metal Mines in India. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Rajhans, G.S.; Malik, O.P.; Tombe, K.D. Respirable Dust and Respirable Silica Exposure in Ontario Gold Mines. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2014, 11, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Figueroa, D.; Maier, R.M.; de la O-Villanueva, M.; Gómez-Alvarez, A.; Moreno-Zazueta, A.; Rivera, J.; Campillo, A.; Grandlic, C.J.; Anaya, R.; Palafox-Reyes, J. The impact of unconfined mine tailings in residential areas from a mining town in a semi-arid environment: Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico. Chemosphere 2009, 77, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, T. , et al., Size fractionation in mercury-bearing airborne particles (HgPM10) at Almadén, Spain: implications for inhalation hazards around old mines. Atmospheric Environment, 2005. 39, p. 6409-6419.

- Saarikoski, S. , et al., Particulate matter characteristics, dynamics, and sources in an underground mine. Aerosol Science and Technology, 2018. 52, p. 114-122.

- Chubb, L.G.; Cauda, E.G. Characterizing Particle Size Distributions of Crystalline Silica in Gold Mine Dust. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mala, H.; Tomasek, L.; Rulik, P.; Beckova, V.; Hulka, J. Size distribution of aerosol particles produced during mining and processing uranium ore. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 157, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.T.; Cauda, E.; Chubb, L.; Krebs, P.; Stach, R.; Mizaikoff, B.; Johnston, C. Complexity of Respirable Dust Found in Mining Operations as Characterized by X-ray Diffraction and FTIR Analysis. Minerals 2021, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.; Mugford, C.; Murray, A.; Shepherd, S.; Woskie, S.R. Characterization of Occupational Exposures to Respirable Silica and Dust in Demolition, Crushing, and Chipping Activities. Ann. Work. Expo. Heal. 2019, 63, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Carey, R.N.; Reid, A.; Driscoll, T.; Glass, D.C.; Peters, S.; Benke, G.; Darcey, E.; Fritschi, L. The Australian Work Exposures Study: Prevalence of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2016, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanvirat, K., N. Chaiear, and T. Choosong, Determinants of respirable crystalline silica exposure among sand-stone workers. Am J Public Health Res, 2018. 6, p. 44-50.

- Mbuya, A.W.; Mboya, I.B.; Semvua, H.H.; E Msuya, S.; Howlett, P.J.; Mamuya, S.H. Concentrations of respirable crystalline silica and radon among tanzanite mining communities in Mererani, Tanzania. Ann. Work. Expo. Heal. 2024, 68, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poormohammadi, A.; Moeini, E.S.M.; Assari, M.J.; Khazaei, S.; Bashirian, S.; Abdulahi, M.; Azarian, G.; Mehri, F. Risk assessment of workers exposed to respirable crystalline silica in silica crushing units in Azandarian Industrial Zone, Hamadan, Iran. J. Air Pollut. Heal. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margan, A.; Verlak, D.; Roj, G.; Fikfak, M.D. Occupational exposure to silica dust in Slovenia is grossly underestimated. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2022, 73, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doney, B.C.; Miller, W.E.; Hale, J.M.; Syamlal, G. Estimation of the number of workers exposed to respirable crystalline silica by industry: Analysis of OSHA compliance data (1979-2015). Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, P.; Mousa, H.; Said, B.; Mbuya, A.; Kon, O.M.; Mpagama, S.; Feary, J. Silicosis, tuberculosis and silica exposure among artisanal and small-scale miners: A systematic review and modelling paper. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2023, 3, e0002085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebert, P.; Andersson, T.; Feychting, M.; Sjögren, B.; Plato, N.; Gustavsson, P. Occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica and acute myocardial infarction among men and women in Sweden. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 80, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.S.; Nandi, S.S.; Deshmukh, A.; Dhatrak, S.V. Exposure profile of respirable crystalline silica in stone mines in India. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2020, 17, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatrak, S.; Nandi, S. Assessment of silica dust exposure profile in relation to prevalence of silicosis among Indian sandstone mine workers: Need for review of standards. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, K.M.; Attfield, M.D.; Wood, J.M.; Syamlal, G. National trends in silicosis mortality in the United States, 1981–2004. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2008, 51, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Chen, J.-Q.; Miller, W.; Chen, W.; Hnizdo, E.; Lu, J.; Chisholm, W.; Keane, M.; Gao, P.; Wallace, W. Risk of silicosis in cohorts of Chinese tin and tungsten miners and pottery workers (II): Workplace-specific silica particle surface composition. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005, 48, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnizdo, E. Risk of silicosis: Comparison of South African and Canadian miners. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1995, 27, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.S. , Characterization of arsenic-hosting solid phases in Giant mine tailings and tailings dust. 2017, Queen's University (Canada).

- Steenland, K.; Brown, D. Silicosis among gold miners: exposure--response analyses and risk assessment. . Am. J. Public Heal. 1995, 85, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P. , et al., Estimating factors to convert Chinese ‘total dust’measurements to ACGIH respirable concentrations in metal mines and pottery industries. Annals of occupational hygiene, 2000. 44, p. 251-257.

- Tsai, C.S.-J.; Shin, N.; Brune, J. Evaluation of Sub-micrometer-Sized Particles Generated from a Diesel Locomotive and Jackleg Drilling in an Underground Metal Mine. Ann. Work. Expo. Heal. 2020, 64, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaapen, A.M.; Albrecht, C.; Becker, A.; Höhr, D.; Winzer, A.; Haenen, G.R.; Borm, P.J.; Schins, R.P. DNA damage in lung epithelial cells isolated from rats exposed to quartz: role of surface reactivity and neutrophilic inflammation. Carcinog. 2002, 23, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. , et al., Essential role of p53 in silica-induced apoptosis. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 2005. 288, p. L488-L496.

- Lalmanach, G.; Diot, E.; Godat, E.; Lecaille, F.; Hervé-Grépinet, V. Cysteine cathepsins and caspases in silicosis. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.S. , Validation of biomarkers for improved assessment of exposure and early effect from exposure to crystalline silica. 2015, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences.

- Puyo, C.A. , et al., Endotracheal intubation results in acute tracheal damage induced by mtDNA/TLR9/NF-κB activity. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 2019. 105, p. 577-587.

- Li, B.; Mu, M.; Sun, Q.; Cao, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Hu, D.; Tao, X.; et al. A suitable silicosis mouse model was constructed by repeated inhalation of silica dust via nose. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 353, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabolli, V.; Badissi, A.A.; Devosse, R.; Uwambayinema, F.; Yakoub, Y.; Palmai-Pallag, M.; Lebrun, A.; De Gussem, V.; Couillin, I.; Ryffel, B.; et al. The alarmin IL-1α is a master cytokine in acute lung inflammation induced by silica micro- and nanoparticles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Dai, X.; Yao, T.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, G.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, M.; He, Y.; Peng, Z.; Hu, G.; et al. Mefunidone alleviates silica-induced inflammation and fibrosis by inhibiting the TLR4-NF-κB/MAPK pathway and attenuating pyroptosis in murine macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Min, H.; Chen, J.; Li, C. Crystalline silica-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes the pathogenesis of silicosis by augmenting proinflammatory interstitial pulmonary macrophages. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 946, 174299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.A.; Beamer, C.A.; Migliaccio, C.T.; Holian, A. Critical Role of MARCO in Crystalline Silica–Induced Pulmonary Inflammation. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 108, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.-L.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Hu, H.-J.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.-Q. Silica-induced ROS in alveolar macrophages and its role on the formation of pulmonary fibrosis via polarizing macrophages into M2 phenotype: a review. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2024, 35, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, G. , et al., Crystalline silica on the lung–environment interface: Impact on immunity, epithelial cells, and therapeutic perspectives for autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2024: p. 103730.

- Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Bruch, J. Exposures to silica mixed dust and cohort mortality study in tin mines: Exposure-response analysis and risk assessment of lung cancer. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoman, K.M.; Halldin, C.N.; Wood, J.; Storey, E.; Johns, D.; Laney, A.S. Current knowledge of US metal and nonmetal miner health: Current and potential data sources for analysis of miner health status. Arch. Environ. Occup. Heal. 2016, 71, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country/Region | Respirable Silica PEL (mg/m3) |

|---|---|

| USA | 0.05 [15] |

| Canada | 0.1 [24] |

| European Union | 0.1 [25] |

| India | 0.15 [26] |

| Australia | 0.05 [27] |

| Britain | 0.1 [24] |

| South Africa | 0.1 [25,28] |

| Italy | 0.1 [24] |

| France | 0.1 [24] |

| China | 0.07 to 0.35 (varies with silica content) [24] |

| MNM Mines | Coal Mines | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Full-shift sampling using gravimetric samplers in breathing zones | Similar full-shift sampling approach |

| Exposure Calculation | 8—hours TWA regardless of shift length | Adjusted based on actual shift length |

| Analytical Methods | X-ray diffraction (XRD) | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Control Measures | Engineering controls like ventilation, additional sampling for verification | Engineering/environmental controls, monitoring compliance with dust limits |

| Study | Sampling Locations (Sites) | No. of Samples |

Instrument | Characteristic Technique | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rautenbach, J. J. (2019) [42] | Iron ore mining environment | Single dust bucket (SDB): 8 monitoring points; Multi-directional dust bucket (MDB): 4 monitoring points; PM10: 3 monitoring points | Single dust bucket (SDB), Multi-directional dust bucket (MDB) | Chemical analysis of dust for 42 elements; PM10 analysis | - The average dust levels in SDB and MDB were below the residential limit of 600 mg/m2/day - PM10 levels remained within limits - Copper and iron concentrations surpassed exposure limits - Wind direction minimally affected dust measurement methods, but wind speed influenced PM10 levels at specific locations - Recommended revising the multi-directional bucket system and enforcing legislation for dust chemical monitoring |

| Entwistle, Jane A., et al. (2019) [43] | Metalliferous mines worldwide, with specific reference to impacts from arsenic, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, uranium, and zinc | Not specified | Not specified (General discussion on monitoring and analysis methods) | Chemical analysis for potentially toxic elements (PTEs,) in vitro and in vivo studies, epidemiological and toxicological assessments | - Mining-related dust contains PTEs, posing risks to human health and ecosystems - A review of epidemiological studies on Pb, As, and Cd exposure shows synergistic neurodevelopmental toxicity from combined mixtures, emphasizing the need for updated toxicological models - Fine particulates (≤2.5 μm) from smelting deposit in alveoli, with oral breathing during exertion increasing exposure- In vivo studies suggest that Fe-rich particles in mine dust contribute to oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to DNA damage and chronic inflammation |

| Keast, D., et al. (1987) [44] |

North-west of Western Australia | 91 samples of respirable fraction | Casella Hextlett sampler with an elutriator | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy ( EDS) analysis for physical and chemical properties, Ames test for mutagenicity, Gamma emission spectra for radioactivity assessment, Animal exposure and intrapleural implantation studies were conducted to evaluate dust inhalation effects | - Approximately 5% of dust particles measured >1 μm, with an average length of 2.5 μm and some reaching 6.5 μm - Fibrous particles were predominantly aluminosilicate or iron-rich, with low silica or alumina levels, none classified as asbestos - Silica content ranged from 1.5% to 11.1%, with most (<61%) samples containing <3.5% silica - All samples tested negative for mutagenicity in the Ames test - Small amounts of 59Fe and 54Mn were detected (<2 pCu/10 g) - Animal exposure and intrapleural implantation of respirable iron ore dust caused interstitial pneumonia, lung damage (e.g., fibrosis, emphysema), and increased tumor rates in rats and mice, but did not induce mesothelioma. |

| Badenhorst, R. (2013) [45] | Opencast iron ore mine: primary-secondary crusher, tertiary crusher, quaternary crusher, and sifting house | Not specified | Static inhalable and respirable samplers, optical particle counters (OPC), condensation particle counters (CPC) | SEM and EDS for physical and chemical characterization | - Inhalable dust levels were high across all process areas, with notable spikes at the primary-secondary crusher - Particle analysis showed a prevalence of 0.3 µm particles, with significant ultrafine particles (<0.3 µm), notably at specific crushers - SEM findings revealed particle agglomeration and splinters - EDS analysis identified predominant elemental compositions, varying across the beneficiation process - Warned of respiratory overexposure and systemic risks from ultrafine particles, potentially leading to lung pathologies |

| Paluchamy, B., & Mishra, D. P. (2022) [46] | Kayad Lead-Zinc Ore Mine (KLZM), Rajasthan, India | Not explicitly mentioned, but data recorded over 10 Load-Haul-Dump (LHD) mucking trips | Grimm Aerosol Spectrometers (Model 1.108) | Size distribution analysis and airflow simulation using Ventsim software | - Remote LHD operator site had high total airborne dust (TAD) levels, mainly ≤10 μm (PM10) - Downcast airflow led to greater dust exposure than upcast airflow - Empirical models estimated alveolic, thoracic, and inhalable dust from total airborne dust (TAD) - Emphasized ventilation management to reduce worker dust exposure |

| Andraos, C. (2019) [47] | Tailings storage facilities (TSFs) | Not specified; multiple bulk samples analyzed | AS200 Jet Sieve Shaker, Electrostatic Classifier Model 3080, condensation particle counter (CPC) Model 3772, Aerodynamic Particle Sizer (APS) Model 3321, Small-Scale Powder Disperser (SSPD) Model 3433, electron spin resonance (ESR) Spectroscopy | Size fractionation, size distribution analysis, surface area and porosity determination, shape, and elemental composition analysis, mineral composition via X-ray diffraction (XRD), elemental composition via inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES), surface activity measurement | - Tailings dusts exhibited in vitro toxicity to human airway cells, indicating potential health risks - Min-U-Sil 5 silica showed the highest toxicity, with tailings dust samples varying in activity and toxicity levels - High levels of Fe in ERGO dust correlated with increased toxicity - Elemental composition, including Cu and Cr, varied among samples, affecting toxicity - Quartz content and surface area influenced toxicity, but were not sole determinants |

| Bandopadhyay, A. K., & Kumari, S. (2013) [48] | Coal and metal (zinc and manganese) mines | Not specified; samples collected from various mine locations | Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer | Direct-on-filter method for quartz determination | - Coal mine dust: Quartz content <1%, except in some cases - Metal mines: Quartz >5% in many areas - Effective in metal mines: Wet drilling, ventilation - Suggested worker rotation in challenging dust suppression areas |

| Arrandale et al. (2018) [49] | Core processing facility operated by a gold mining company in Northern Ontario, Canada | 19 personal and 10 area samples; 16 personal and 9 area samples analyzed after exclusions | SKC aluminum cyclones, pre-weighed 37mm Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) filters, sampling pumps | Gravimetry (NIOSH method 0600), FTIR (NIOSH method 7602) for respirable dust and silica analysis | - Personal respirable dust concentration mean: 0.46 mg/m3; stationary: 0.41 mg/m3 - Core saw rooms had highest levels: 0.63 mg/m3 - Silica: 69% of personal and 67% area samples were below the limit of detection (LOD) - Three samples exceeded ACGIH TLV for respirable crystalline silica |

| Hart et al. (2018) [50] | Three Northwestern U.S. metal/nonmetal mines | 75 dust samples | FTIR spectrometry and XRD | Direct-on-filter RCS evaluation using FTIR and comparison with XRD | - Strong positive correlations between FT-IR and XRD respirable crystalline silica (RCS) concentrations were observed, with Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from 0.84 to 0.97 across the three mines - FTIR showed lower mean RCS concentrations than XRD - Mean differences ranged from -4 to -133 µg/m3, with percent errors from 12% to 28% - Significant improvement post-calibration at two mines, with mean differences of -0.03 and -0.02 on a log scale |

| Slouka et al. (2022) [51] | Laboratory setting simulating limestone cutting | Multiple samples from three pick wear stages (new, moderately worn, worn) | Nylon Dorr-Oliver cyclones, Tsai Diffusion Sampler (TDS), vacuum for deposited particles, SEM for imaging | Collection of airborne and deposited particles for concentration, mineralogy, shape, and size distribution analysis | - Airborne dust rises with worn picks, indicating increased generation- All picks emit dust with hazardous silica minerals- Particle shape analysis found no significant differences- Particle size distribution varied, with worn picks generating smaller airborne particles and the opposite for deposited particles |

| Stach et al. (2020) [52] | Three limestone mines in the USA. One sandstone sample from Berlin, Germany. |

A total of 9 synthetic calibration mixtures were created. 4 natural samples were used for validation: D4, D9, D10 (limestone samples from the USA). SSB (sandstone sample from Berlin). |

- For FTIR Measurements: Portable Bruker Alpha FTIR spectrometer equipped with Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) and a transmission assembly- For SEM/EDX Measurements: Quanta 3D FEG FIB-SEM dual-column system | - Particle Size Characterization: Agate mortar grinding for inhalable (>5 μm) and respirable (≤4 μm) particles - attenuated total reflection (ATR) Transmission, and DRIFTS Measurements: Analyzing samples without dilution and with KBr dilution for DRIFTS - Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) Verification: Ensuring mineral purity and identifying impurities |

- Particle size decrease maximized IR spectrum signals, nearing respirable range- Strong correlations between FTIR measurements and particle sizes found during calibration and validation with real-world samples - Combined DRIFTS and transmission IR model allowed mineral quantification and particle size classification, facilitating rapid field dust exposure assessment |

| Jaggard, H. (2012) [53] | New Calumet Mine, Quebec, Canada; former Pb-Zn mine | Not specified; airborne dust and near-surface tailings samples | (Proton Induced X-ray Emission Spectroscopy) PIXE Cascade Impactor, environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM), synchrotron techniques (microXRD, micro X-ray Fluorescence (XRF)) | Bioaccessibility tests, total metal content, grain size distribution, Pb speciation | - Galena identified as the most abundant Pb-bearing phase in pH-neutral tailings, with cerussite and hydrocerussite forming alteration rims on galena grains - Bioaccessibility tests showed 0-0.05% bioaccessible Pb in lung fluid and 23-69% bioaccessible Pb in gastric fluid |

| Kumari et al. (2011) [54] | Zinc mines in Rajasthan and Orissa, Manganese mines in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, India | Locations vary; 30 for zinc mines, 52 for manganese mines | AFC-123 (Casella London) personal sampler, FTIR (Model 1760X, Perkin-Elmer) for direct on-filter analysis | Sampling on pre-weighed GLA-5000 PVC membrane filters, FTIR for quartz content analysis | - Dust and quartz concentrations varied across mine types and locations - Health risk assessments spanned from Low to Very High based on maximum exposure limit (MEL) in India and the USA - Some mining and crusher sites exhibited high quartz content and dust despite preventive measures - Effective dust control observed in some areas via wet drilling and ventilation, while others need additional measures like worker rotation - Calls for international consensus on MEL standards for comparable health risk assessments |

| Verma et al. (2014) [55] | 8 operating gold mines in Ontario, Canada | 288 long-term personal respirable dust air samples | DuPont personal sampling pump, BCIRA metal cyclone, XRD method | - Personal long-term air sampling covering full shifts (7–8 hrs.), measurement of respirable dust and silica | - Mean respirable dust: 1 mg/m3 - Mean respirable silica: 0.08 mg/m3 - Mean % silica in respirable dust: 7.5% - Potential feasibility of replacing konimeter assessment with gravimetric sampling indicated by data |

| Meza-Figueroa et al. (2009) [56] | , Nacozari mining town in Sonora, northern Mexico | 70 mine tailings, 7 efflorescence salts, Soils (S1–S6), Residential soils (C1–C21), Road dust (RD1–RD3) | Innov-XXT400 portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer, Perkin-Elmer 4200 DV ICP for ICP-AES analysis, X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) | - Collection and analysis of tailings, soils, and dust for metal content, statistical analysis including principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis to assess data | - Mine tailings generally contained low levels of certain metals but higher concentrations of Ag, Cu, and Hg - Efflorescence salts indicated significant metal accumulation - Urban soils and road dust showed evidence of metal dispersion from mine tailings, especially Cu and As - Statistical analysis confirmed mine tailings as the metal source and identified spatial clusters linked to wind dispersion. - Climate likely influenced metal mobility and dispersion mechanisms |

| Moreno et al. (2005) [57] | Las Cuevas mine waste dumps, Almadén, Spain | Not specified | SEM, (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) ICP-MS, XRD | SEM for particle analysis, ICP-MS for chemical analysis, XRD for mineralogical composition | - High levels of mercury contamination, especially in PM10- Presence of cinnabar, native mercury, and chlorine-bearing compounds |

| Saarikoski et al. (2018) [58] | Underground chrome mine, Kemi, Northern Finland | Not specified | Online instruments with high time-resolution, offline particulate sampling for elemental and ionic analyses | High time-resolution monitoring, elemental and ionic analyses | - PM1 mainly from diesel engine emissions - Sub-micrometer particles also from explosives combustion (nitrate, ammonium) - PM1 composition: 62% organic matter, 30% black carbon, 8% major inorganic species - Elements like Al, Si, Fe, and Ca peaked above 1 µm, indicating a mineral dust origin from mechanical activities such as crushing and tunnel excavation. - Average particle number concentration: (2.3 ± 1.4)*104 #/cm3 - Particle size distribution peaked between 30 and 200 nm, with a distinct mode <30 nm - Origin of nano-size particles required further investigation |

| Chubb, L., & Cauda, E. (2017) [59] | Alaska, Nevada, South Africa gold mines | Not specified | TSI 3321 APS, TSI scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS), MOUDI-110R, 10-mm nylon cyclones, ICP-MS, SEM, XRD | Aerodynamic and electromobility size distribution measurement, mineral composition analysis, silica quantification by IR and XRD | - Dusts primarily quartz silica, with varied mineral compositions - The count median particle diameter (CMD) and mass median diameter (MMD) ranged from 498 nm (Nevada) to 1680 nm (Alaska) - Silica content varied by size fraction - Silica quantified using both IR and XRD to address potential biases - Particle mass size distributions for total dust and silica component showed slight differences |

| Malá et al. (2016) [60] | Czech Republic, specifically in the Rožná I uranium mine | 13 | Cascade Impactors (Sierra Andersen SA 236 model), Gamma Spectrometry Analysis (HPGe detectors) | Aerosol Particle Size Distribution, Activity Concentration of 226Ra, Log-normal Distribution Characterization | - 226Ra concentrations: 5.2×10−3 to 5.1×10−2 Bq/m3 - activity median aerodynamic diameter (AMAD): 2.0 μm to 14.2 μm, geometric standard deviation (GSDs): 2.8 to 12.5 - Highest activity in coarse particles (>10 μm) - 13-22% activity in aerosol aerodynamic diameters (ADs) <0.39 μm - AMADs: 4.2 μm (F, EOC), 9.8 μm (CP) - Radon emanation coefficient: 0.39, no significant AD variations |

| Walker et al. (2021) [61] | 56 sites in the USA, with additional sites in Canada, South Africa, Chile, and Australia, Included mining commodities such as gold, copper, limestone, granite, iron, sand & gravel, and other metals | 130 mine dust samples analyzed | GK2.69 sampler and AirTouch pump | XRD and FTIR analysis | - Most samples exhibited approximately 5 mineral phases including α-Quartz, Muscovite, Plagioclase, K-feldspar, and Chlorite - FTIR accurately predicted the correct mineral phase 77% of the time, showcasing its potential for on-site monitoring of respirable dust mineralogy |

| Bello et al. (2019) [62] | several sites in Massachusetts, USA, across several construction-related activities | 51 personal breathing zone samples from workers and 33 area samples at the perimeter of demolition and crushing sites | 37 mm diameter PVC filters, two-piece cassettes housed in BGI 4 respirable cyclones, GilAir 3 sampling pumps | Gravimetric analysis, FTIR Spectro photometry | - Personal 8-hour Time-Weighted Average (TWA) RCS exposures surpassed the OSHA PEL - Emphasized the difficulty in managing crystalline silica exposures to meet the new OSHA PEL |

| Si et al. (2016) [63] | Across Australia | 4,993 | Did not directly use air sampling instruments. | - The assessment relied on workers' self-reported tasks and the implementation of control measures at their workplace.- The evaluation was conducted using OccIDEAS, an application designed for assessing job-related exposures. | - Miners and construction workers were most prone to experiencing high-level RCS exposure. - In 2012, 6.4% of respondents were identified as being exposed to RCS at work |

| Chanvirat et al. (2018) [64] | Northeastern Thailand, sandstone processing | 88 | Gravimetric method (NIOSH 600) for respirable dust (RD) and NIOSH 7601 spectrophotometer for RCS | Personal air sampling from the breathing zone of workers throughout the 8-hour working day, analyzed according to the NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods | - Geometric mean (GM) of RCS exposure was 0.10 mg/m3, with the highest levels observed among stone cutters in mines at 0.14 mg/m3, followed by stone carvers at 0.10 mg/m3 |

| Mbuya et al. (2024) [65] | Mererani Mines, Northern Tanzania | 66 | Personal dust samples (PDS) | Infrared absorption Spectrophotometry technique | - Median TWA concentration of RCS in mining pits was 1.23 mg/m3 - 65 out of 66 analyzed PDS samples from mining pits showed RCS concentrations exceeding the OSHA PEL of 0.05 mg/m3 |

| Poormohammadi et al. (2021) [66] | Hamadan, Iran (silica stone crushing units) | Not specified | Average-flow personal sampling pump (Gilian- LFS 113DC), PVC filter (37-mm, 5-µm), FTIR (Elmer Perkin/Tow Spectrum device) | FTIR | - - Average exposure to RCS ranged from 0.14 to 1.70 mg/m3, with the highest exposure observed in stamping machine operator |

| Margan et al. (2022) [67] | Slovenia (targeting industries with a high risk of RCS exposure, including mining, and natural stone processing) | 18,064 | Online questionnaire | Lung radiographs | - Lung radiograph reviews revealed that about one-third of exposed workers exhibited lung changes associated with silicosis - A significant underestimation of RCS exposure was observed, with only 8.3% of companies conducting dust concentration measurements and 1.81% measuring silica concentration |

| Doney et al. (2020) [68] | United States (various industries) | 27,700 RCS air samples | OSHA compliance inspection sampling data | Not specified | - The construction industry was identified with the highest levels of RCS exposure, with around 100,000 workers exposed above the RCS recommended exposure limit (REL) |

| Howlett et al. (2023) [69] | 10 countries (Artisanal and small-scale mining) | 18 studies involving 29,562 miners | gravimetric analysis and NIOSH method 7500 | Logistic and Poisson regression models were used to estimate silicosis prevalence and tuberculosis incidence at different distributions of cumulative silica exposure. | - RCS intensity was notably high, ranging from 0.19 to 89.5 mg/m3, with respiratory symptoms commonly reported - Simple interventions like wet drilling or improved ventilation can reduce dust exposure by up to 80%, offering substantial health benefits at low cost. |

| Wiebert et al. (2023) [70] | Sweden (workers in various industries known for RCS exposure) | 1,085,853 individuals | Job-exposure matrix (JEM) | RCS was linked to job titles using the JEM, and health outcomes acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were determined from nationwide registers; cox regression was used to estimate HRs and 95% CIs, adjusted for demographic factors | - The risk of AMI increased with cumulative exposure, especially notable in the highest quartile of exposure - Among manual workers exposed to RCS, women exhibited a significantly higher adjusted risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) with a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 1.29, compared to men with HR 1.02 |

| Prajapati et al. (2020) [71] | Stone mines in India | 71 personal dust samples | Sidekick-51MTX dust samplers, PVC filters and plastic cyclones | FTIR, gravimetric analysis | - Mean RCS concentrations: Sandstone mines: 0.12 mg/m3 Masonry and granite stone mines: 0.17 mg/m3 - RCS concentrations in granite and masonry mines surpassed the Directorate General of Mine Safety in India limit of 0.15 mg/m3, indicating a necessity for standard adjustments to align with international standards |

| Dhatrak and Nandi (2020) [72] | Sandstone mines in India | 26 personal dust samples | Personal dust sampler Side Kick Model no. MTX 51, PVC 37 mm filter paper, FTIR (Bruker make Alpha T model) | Free silica content was estimated FTIR following NIOSH-7602 methodology | - Radiographs compatible with silicosis were seen in 12.3% of workers, the mean concentration was found to be 0.12 mg/m3, with 70% of the samples falling below India's prescribed safety standard of 0.15 mg/m3 |

| Bang et al. (2008) [73] | United States, with a focus on industries such as mining and quarrying, metal and mineral processing, and occupations associated with high risk of silicosis mortality | Analysis of 6,326 deaths with silicosis from 1981 to 2004 | Analyzed mortality data rather than directly measuring air samples | Trends and associations with occupation and industry were identified through analysis of death certificates and proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) based on National Occupational Respiratory Mortality Surveillance (NORMS) data | - Silicosis mortality rates declined from 2.4 per million in 1981 to 0.7 per million in 2004 - Industries with significantly elevated PMRs included mining and quarrying - Occupations with elevated PMRs were linked to metal and mineral processing |

| Harrison et al. (2005) [74] | Chinese tin and tungsten mines and pottery workplaces | 47 respirable dust samples were collected from 13 worksites | NIOSH cyclone separator, PVC filter collector for respirable dust, multiple-voltage scanning electron microscopy–energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (MVSEM-EDS) | Comparing silicon-to-aluminum ratios at different electron beam voltages to distinguish between clay-coated silica particles and those with homogeneous aluminum contamination | - Pottery workplaces had the highest average of alumino-silicate occlusion on silica particles (45%), followed by tin mines (18%) and tungsten mines (13%) |

| Hnizdo (1995) [75] | South African gold miners and Canadian hard rock miners | Not specified | Standard thermal precipitator | The analysis involved converting historical respirable surface area measurements to gravimetric units (mg/m3) and approximating the average concentration of quartz in respirable dust | - The risk of silicosis is comparable at certain levels of cumulative dust exposure but emphasizing differences in exposure levels, fibrogenicity of silica dust, and the proportion of quartz in respirable dust |

| Bailey (2017) [76] | Abandoned gold mine in Canada, specifically focusing on tailings impoundments and airborne tailings dust | Material sampled from three tailings impoundments | Total suspended particulate (TSP) high volume air sampler, ICP-OES and ICP-MS for bulk chemical data SEM, Electron Microprobe Analysis (EMPA), µXRD, µXRF for mineralogical data; X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) for oxidation state data of arsenic |

Combination of ICP methods for chemical analysis, scanning electron microscopy and electron microprobe analysis for mineralogical identification, and synchrotron-based techniques for detailed mineral phase analysis | - Dust primarily contained Fe-oxides as the As host, with very little arsenic trioxide found in tailings and none in dust samples - The findings suggest that nearby soils might present a higher risk to human health due to historic emissions, given the low arsenic trioxide levels in tailings and dust |

| Steenland and Brown (1995) [77] | Gold miners in the United States | 3,330 gold miners | The analysis was based on historical exposure data, applying a job-exposure matrix to estimate cumulative exposures for each job category in the mine | Silicosis cases were identified through death certificates and from two cross-sectional radiographic surveys in 1960 and 1976, using International Labor Organization (ILO) categories for x-ray confirmed cases | - Found a significant exposure-response relationship between cumulative silica exposure and the risk of silicosis, with the risk increasing with cumulative exposure |

| Gao et al. (2000) [78] | Metal mines and pottery industries in China | 100+ | 10 mm nylon cyclones, multi-stage 'cassette' impactors, Chinese total dust samplers for airborne dust sampling | Comparison of respirable dust concentrations to 'total dust' concentration, conversion factors developed to estimate respirable dust concentrations from historical Chinese 'total dust' measurements |

- Conversion factors varied across industries, with the lowest in the pottery industry |

| Tsai et al. (2020) [79] | Edgar Experimental Mine, which is operated by the Colorado School of Mines | Multiple samples collected over 4 hours | Sioutas cascade impactor, respirable cyclone sampler, and a Tsai diffusion sampler (TDS) for airborne particle collection, real-time instruments (NanoScan SMPS and ptical Particle Sizer (OPS)) for particle number concentrations measurement, TEM and SEM for particle morphology and elemental composition | Combined use of gravimetric analysis for mass concentration and number metrics for particle count; utilized a unique sampler designed for nanoparticles and respirable particle characterization | - Drilling produced sub-micrometer particles peaking at ~50 nm, with concentrations >1.7 × 10⁶ particles/cm3 Diesel exhaust showed peak particle sizes at ~30 nm, averaging 5.4 × 10⁵ particles/cm3 Mass concentrations were low (<0.6 mg/m3) but high particle counts indicated substantial exposure risk Particles included elements like Cu, Fe, Si, Al, and Mg, suggesting metallic and mineral dust origin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).