Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Footsteps of Trailblazers in Immunization

Vaccinology Today

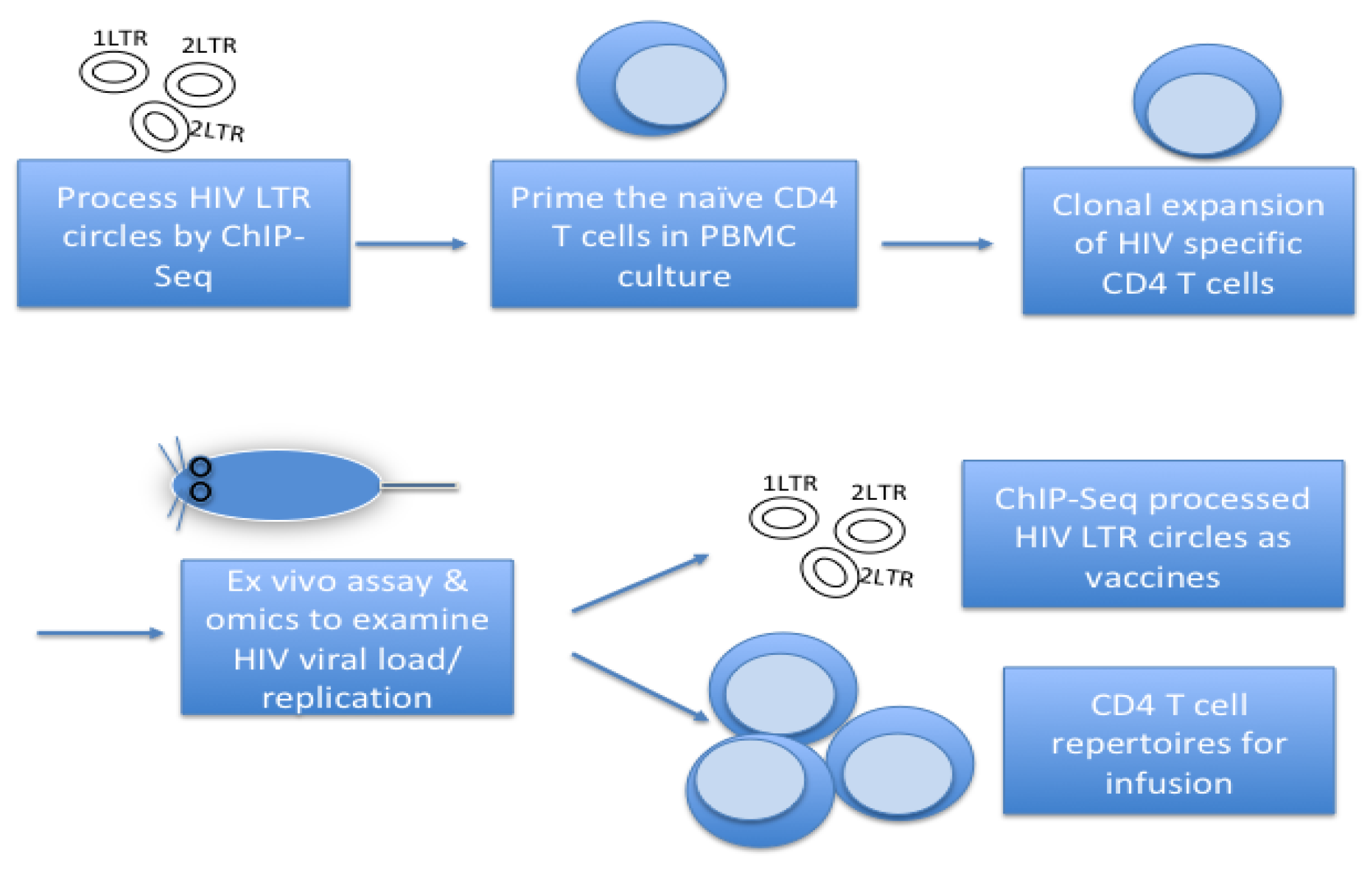

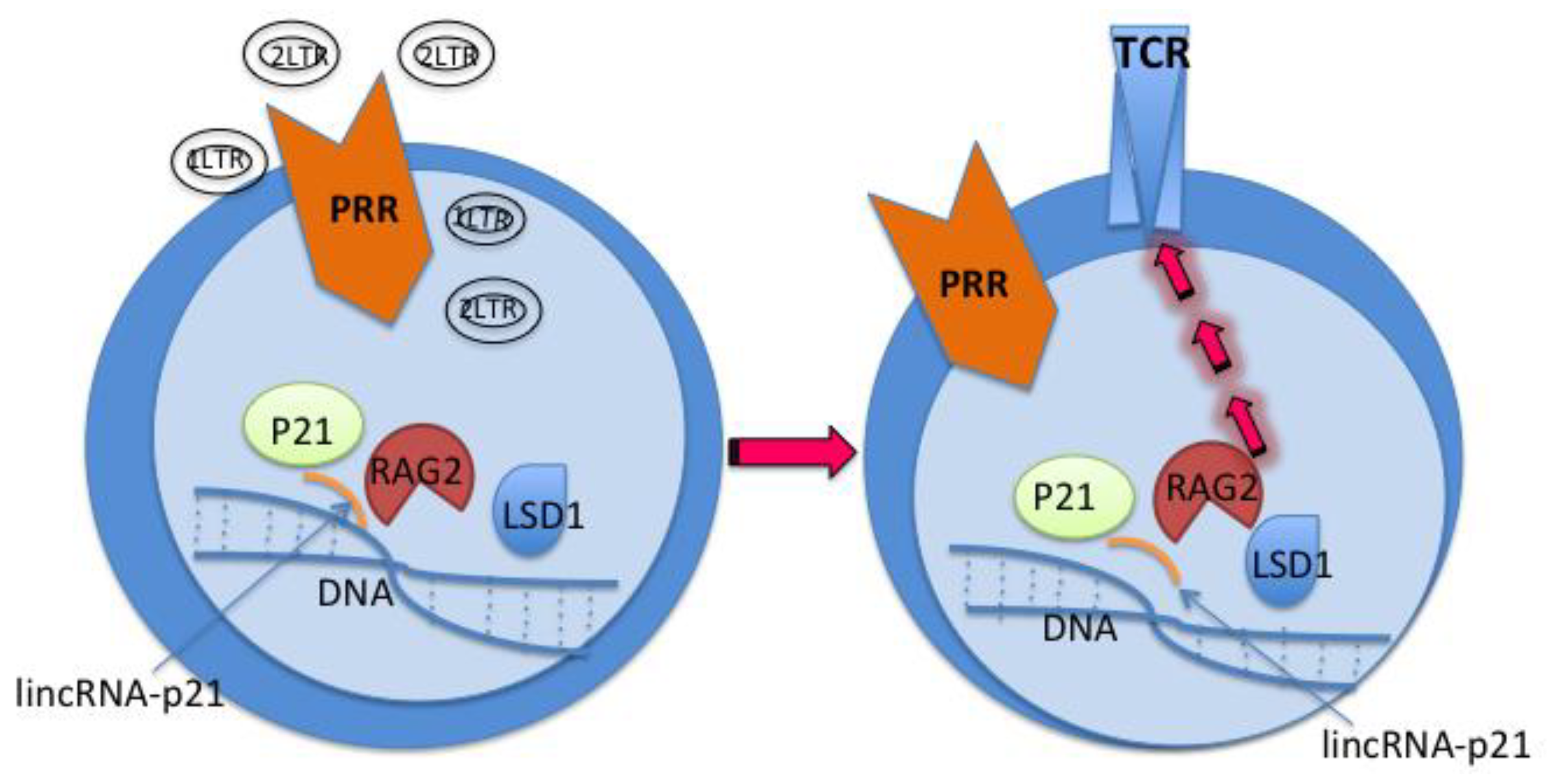

A Leap Forward in Immunization by cVacc Elicited Epigenetic Immunity

- Processing 2-/1-LTR circles by ChIP-seq, etc.

- Exposing the 2-/1-LTR circles to cell cultures

- Colony formation assay for CD4 T-cells

- Testing CD4 T-cells antigen specific function and memory in vitro and in vivo

Discussion, Conclusion, and Future Direction

References

- Glynn, I. , Glynn, J. The Life and Death of Smallpox. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- U.S. Military and Vaccine History. HistoryOfVaccines.org. Available online: https://historyofvaccines.org › how-are-vaccines-made (accessed on 2025 Mar 30).

- Joklik, Willett, Amos, Wilfer. Zinsser Microbiology. 19th Edition. Appleton & Lange, 1988.

- Plotkin, SA. Vaccines: past, present and future. Nat Med. 2005 Apr;11(4 Suppl):S5-11.

- Norrby, E. Yellow fever and Max Theiler: the only Nobel Prize for a virus vaccine. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 2779–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, G.C. Adenovirus 4 and 7 Vaccine: New Body Armor for U.S. Marine Corps Officer Trainees. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 221, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Askenase, P.; Jaenisch, R.; Crumpacker, C.S. Approaches to pandemic prevention – the chromatin vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1324084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talotta, R. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines as hypothetical epigenetic players: Results from an in silico analysis, considerations and perspectives. Vaccine 2023, 41, 5182–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya R, Shamim U, Mishra P, Swaminathan A, Raina A, Tarai B, Budhiraja S, Pandey R. Intertwined Dysregulation of Ribosomal Proteins and Immune Response Delineates SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Breakthroughs. Microbiol Spectr. 2023 Jun 15;11(3):e0429222.

- Mortari, E.P.; Ferrucci, F.; Zografaki, I.; Carsetti, R.; Pacelli, L. T and B cell responses in different immunization scenarios for COVID-19: a narrative review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1535014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, P.; Korosec, C.S.; Budylowski, P.; Chau, S.L.L.; Pasculescu, A.; Qi, F.; Delgado-Brand, M.; Tursun, T.R.; Mailhot, G.; Dayam, R.M.; et al. mRNA vaccine-induced SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IFN-γ and IL-2 T-cell responses are predictive of serological neutralization and are transiently enhanced by pre-existing cross-reactive immunity. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0168524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonis, A.; Theobald, S.J.; E Koch, A.; Mummadavarapu, R.; Mudler, J.M.; Pouikli, A.; Göbel, U.; Acton, R.; Winter, S.; Albus, A.; et al. Persistent epigenetic memory of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in monocyte-derived macrophages. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2025, 21, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, E.D.; Watson, J.D.; Collins, F.S. Human Genome Project: Twenty-five years of big biology. Nature 2015, 526, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.A.; DePaola, R.V. Human endogenous retroviruses: our genomic fossils and companions. Physiol. Genom. 2023, 55, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium; Kundaje, A. ; Meuleman, W.; Ernst, J.; Bilenky, M.; Yen, A.; Heravi-Moussavi, A.; Kheradpour, P.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 2015, 518, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ENCODE Project Consortium; Moore, J. E.; Purcaro, M.J.; Pratt, H.E.; Epstein, C.B.; Shoresh, N.; Adrian, J.; Kawli, T.; Davis, C.A.; Dobin, A.; et al. Expanded encyclopaedias of DNA elements in the human and mouse genomes. Nature 2020, 583, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, J.; Gabdank, I.; Luo, Y.; Lin, K.; Sud, P.; Myers, Z.; Hilton, J.A.; Kagda, M.S.; Lam, B.; O'Neill, E.; et al. The ENCODE Portal as an Epigenomics Resource. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2019, 68, e89–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.A.; Hitz, B.C.; Sloan, C.A.; Chan, E.T.; Davidson, J.M.; Gabdank, I.; Hilton, J.A.; Jain, K.; Baymuradov, U.K.; Narayanan, A.K.; et al. The Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): data portal update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D794–D801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehrsson, E.C.; Choudhary, M.N.K.; Sundaram, V.; Wang, T. The epigenomic landscape of transposable elements across normal human development and anatomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, V.; Harris, R.A.; Onuchic, V.; Jackson, A.R.; Charnecki, T.; Paithankar, S.; Subramanian, S.L.; Riehle, K.; Coarfa, C.; Milosavljevic, A. Epigenomic footprints across 111 reference epigenomes reveal tissue-specific epigenetic regulation of lincRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6370–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang JL, Crumpacker CS. Towards a Cure, does host immunity play a role? mSphere. 2017; 2:e00138-17 (and references therein).

- Zhang JL, Crumpacker CS. An integrative immunobiology and inflammation study on cytomegalovirus. Integrative Immunobiology and Inflammation 2016; [S.l.] v. 1, n. 1. [Available online to 2018].

- Zhang J, Crumpacker C. HIV UTR, LTR, and Epigenetic Immunity. Viruses. 2022;18;14(5): 1084.

- Cullen, H.; Schorn, A.J. Endogenous Retroviruses Walk a Fine Line between Priming and Silencing. Viruses 2020, 12, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, J.; Vincendeau, M. SnapShot: Human endogenous retroviruses. Cell 2022, 185, 400–400.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazer, V.; Bonaventura, P.; Tonon, L.; Michel, E.; Mutez, V.; Fabres, C.; Chuvin, N.; Boulos, R.; Estornes, Y.; Maguer-Satta, V.; et al. HERVs characterize normal and leukemia stem cells and represent a source of shared epitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 1200–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, F.; Kitsou, K.; Magiorkinis, G. HERVs: Expression Control Mechanisms and Interactions in Diseases and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Genes 2024, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, T.P.; Magiorkinis, G. Epigenetic Control of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Expression: Focus on Regulation of Long-Terminal Repeats (LTRs). Viruses 2017, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.H.; Gilbert, M.; E Ivan, M.; Komotar, R.J.; Heiss, J.; Nath, A. The role of human endogenous retroviruses in gliomas: from etiological perspectives and therapeutic implications. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, D.; Fstkchyan, Y.S.; Ho, J.S.Y.; Cheon, Y.; Patel, R.S.; Degrace, E.J.; Mzoughi, S.; Schwarz, M.; Mohammed, K.; Seo, J.-S.; et al. Nuclear RNA catabolism controls endogenous retroviruses, gene expression asymmetry, and dedifferentiation. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 4255–4271.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchasovnikarova, I.A.; Timms, R.T.; Matheson, N.J.; Wals, K.; Antrobus, R.; Göttgens, B.; Dougan, G.; Dawson, M.A.; Lehner, P.J. Epigenetic silencing by the HUSH complex mediates position-effect variegation in human cells. Science 2015, 348, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer TJ, Rosenkrantz JL, Carbone L, Chavez SL. Endogenous Retroviruses: With Us and against Us. Front Chem. 2017 Apr 7;5:23.

- Reiss, D.; Mager, D.L. Stochastic epigenetic silencing of retrotransposons: Does stability come with age? Gene 2007, 390, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, M.; Faure-Dupuy, S. Virus hijacking of host epigenetic machinery to impair immune response. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0065823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capparelli R, Iannelli D. Epigenetics and Helicobacter pylori. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Feb 3;23(3):1759.

- Kim, E.-J.; Ma, X.; Cerutti, H. Gene silencing in microalgae: Mechanisms and biological roles. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhya, D.; Basu, A. Epigenetic modulation of host: new insights into immune evasion by viruses. J. Biosci. 2010, 35, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun JC, Lopez-Verges S, Kim CC, DeRisi JL, Lanier LL. NK cells and immune „memory”. J Immunol. 2011 Feb 15;186(4):1891-7.

- Netea, M.G.; Quintin, J.; van der Meer, J.W. Trained Immunity: A Memory for Innate Host Defense. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Ifrim, D.C.; Saeed, S.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; de Jong, D.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 17537–17542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.; Jacobs, C.; Xavier, R.J.; van der Meer, J.W.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. BCG-induced trained immunity in NK cells: Role for non-specific protection to infection. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 155, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, W.B.; Netea, M.G.; Kater, A.P.; van der Velden, W.J. 'Trained immunity: consequences for lymphoid malignancies. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourbal, B.; Pinaud, S.; Beckers, G.J.M.; Van Der Meer, J.W.M.; Conrath, U.; Netea, M.G. Innate immune memory: An evolutionary perspective. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 283, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, L.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P.; Keating, S.T. Getting to the Marrow of Trained Immunity. Epigenomics 2018, 10, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden CDCC, Noz MP, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP, Keating ST. Epigenetics and Trained Immunity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018 Oct 10;29(11):1023-1040.

- Fok, E.T.; Davignon, L.; Fanucchi, S.; Mhlanga, M.M. The lncRNA Connection Between Cellular Metabolism and Epigenetics in Trained Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Andrés, J.; AB Joosten, L.; Netea, M.G. Induction of innate immune memory: the role of cellular metabolism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019, 56, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.M.; Mills, K.H.G.; Basdeo, S.A. The Effects of Trained Innate Immunity on T Cell Responses; Clinical Implications and Knowledge Gaps for Future Research. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, K.T.M.; Mills, K.H. Trained Innate Immunity in Hematopoietic Stem Cell and Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation 2021, 105, 1666–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, P.; Jayaseelan, V.P. Implication of epitranscriptomics in trained innate immunity and COVID-19. Epigenomics 2021, 13, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain BN, Tran BT, Luna PN, Cao R, Le DT, Florez MA, Maneix L, Toups JD, Morales-Mantilla DE, Koh S, Han H, Jaksik R, Huang Y, Catic A, Shaw CA, King KY. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells confer cross-protective trained immunity in mouse models. iScience. 2023 Aug 9;26(9):107596.

- Stier, S.; Cheng, T.; Forkert, R.; Lutz, C.; Dombkowski, D.M.; Zhang, J.L.; Scadden, D.T. Ex vivo targeting of p21Cip1/Waf1 permits relative expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 2003, 102, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Attar, E.; Cohen, K.; Crumpacker, C.; Scadden, D. Silencing p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 expression increases gene transduction efficiency in primitive human hematopoietic cells. Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Scadden, D.T.; Crumpacker, C.S. Primitive hematopoietic cells resist HIV-1 infection via p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng J, Ke Q, Jin Z, Wang H, Kocher O, Morgan J, Crumpacker C, Zhang JL. Cytomegalo-virus Infection Causes an Increase of Arterial Blood Pressure. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5(5)e: 1000427.

- Zhang, J.; Crumpacker, C.S. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in HIV/AIDS and immune reconstitution. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang JL, Poznansky M, Crumpacker CS. Naïve and memory CD4+ T-cells in HIV eradication and immunization. J Infect Dis 2012; 206(4): 617-8.

- Zhang JL, Crumpacker CS. Eradication of HIV and Cure of AIDS, Now and How? Front Immunol 2013; 4:337.

- Zhang, J.; Crumpacker, C. Hematopoietic Stem and Immune Cells in Chronic HIV Infection. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Askenase, P.; Crumpacker, C.S. Systems Vaccinology in HIV Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara, K.; Vahedi, G.; Ghoreschi, K.; Yang, X.-P.; Nakayamada, S.; Kanno, Y.; O’shea, J.J.; Laurence, A. Helper T-cell differentiation and plasticity: insights from epigenetics. Immunology 2011, 134, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayamada, S.; Kanno, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Jankovic, D.; Lu, K.T.; Johnson, T.A.; Sun, H.-W.; Vahedi, G.; Hakim, O.; Handon, R.; et al. Early Th1 Cell Differentiation Is Marked by a Tfh Cell-like Transition. Immunity 2011, 35, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayamada, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kanno, Y.; O'Shea, J.J. Helper T cell diversity and plasticity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara, K.; Poholek, A.; Vahedi, G.; Laurence, A.; Kanno, Y.; Milner, J.D.; O’shea, J.J. Mechanisms underlying helper T-cell plasticity: Implications for immune-mediated disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G. , Wei L., Zhu J., Zang C., Hu-Li J., Yao Z., Cui K., Kanno Y., Roh T.Y., Watford W.T., et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167.

- Vahedi, G.; Kanno, Y.; Sartorelli, V.; O'Shea, J.J. Transcription factors and CD4 T cells seeking identity: masters, minions, setters and spikers. Immunology 2013, 139, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Georgakilas, G.; Petrovic, J.; Kurachi, M.; Cai, S.; Harly, C.; Pear, W.S.; Bhandoola, A.; Wherry, E.J.; Vahedi, G. Lineage-Determining Transcription Factor TCF-1 Initiates the Epigenetic Identity of T Cells. Immunity 2018, 48, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durek, P.; Nordström, K.; Gasparoni, G.; Salhab, A.; Kressler, C.; de Almeida, M.; Bassler, K.; Ulas, T.; Schmidt, F.; Xiong, J.; et al. Epigenomic Profiling of Human CD4+ T Cells Supports a Linear Differentiation Model and Highlights Molecular Regulators of Memory Development. Immunity 2016, 45, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issuree, P.D. , Day K., Au C., Raviram R., Zappile P., Skok J.A., Xue H.H., Myers R.M., Littman D.R. Stage-specific epigenetic regulation of CD4 expression by coordinated enhancer elements during T cell development. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3594.

- Maqbool, M.A.; Pioger, L.; El Aabidine, A.Z.; Karasu, N.; Molitor, A.M.; Dao, L.T.; Charbonnier, G.; van Laethem, F.; Fenouil, R.; Koch, F.; et al. Alternative Enhancer Usage and Targeted Polycomb Marking Hallmark Promoter Choice during T Cell Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiano, J.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Vahedi, G. Enhancing our understanding of enhancers in T-helper cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 2998–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, S.; O'Shea, J.J.; Vahedi, G. Super-enhancers: Asset management in immune cell genomes. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukrinsky, M.; Sharova, N.; Stevenson, M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 2-LTR circles reside in a nucleoprotein complex which is different from the preintegration complex. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 6863–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, A.; Vargas, J.; Keller, M.; Jones, S.; Mosoian, A.; Gurtman, A.; Cohen, A.; Parkas, V.; Wallach, F.; Chusid, E.; et al. Circular Viral DNA and Anomalous Junction Sequence in PBMC of HIV-Infected Individuals with No Detectable Plasma HIV RNA. Virology 2002, 292, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwan, I.D.; Karnowski, H.L.; Bogerd, H.P.; Tsai, K.; Cullen, B.R. Reversal of Epigenetic Silencing Allows Robust HIV-1 Replication in the Absence of Integrase Function. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geis, F.K.; Kelenis, D.P.; Goff, S.P. Two lymphoid cell lines potently silence unintegrated HIV-1 DNAs. Retrovirology 2022, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ross, A.E.; Desiderio, S. Cell Cycle-dependent Accumulation in Vivo of Transposition-competent Complexes between Recombination Signal Ends and Full-length RAG Proteins. 279, 8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dordai, D.I.; Lee, J.; Desiderio, S. A Conserved Degradation Signal Regulates RAG-2 Accumulation during Cell Division and Links V(D)J Recombination to the Cell Cycle. Immunity 1996, 5, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.C.; Desiderio, S. Cell cycle regulation of V(D)J recombination-activating protein RAG-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994, 91, 2733–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews AG, Oettinger MA. Regulation of RAG transposition. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;650:16-31.

- Teng G, Schatz DG. Regulation and Evolution of the RAG Recombinase. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:1-39.

- Jiang, H.; Chang, F.-C.; Ross, A.E.; Lee, J.; Nakayama, K.; Desiderio, S. Ubiquitylation of RAG-2 by Skp2-SCF Links Destruction of the V(D)J Recombinase to the Cell Cycle. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner A, Hallam SJ, Nielsen SJ, Cuadra GI, Berges BK. Development of human B cells and antibodies following human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to Rag2(-/-)γc(-/-) mice. Transpl Immunol. 2015 Jun;32(3):144-50.

- Fuente, C.; Maddukuri, A.; Kehn, K.; Baylor, S.Y.; Deng, L.; Pumfery, A.; Kashanchi, F. Pharmacological Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors as HIV-1 Antiviral Therapeutics. Curr. HIV Res. 2003, 1, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Tungaturthi, P.K.; Ayyavoo, V.; Ghafouri, M.; Ariga, H.; Khalili, K.; Srinivasan, A.; Amini, S.; E Sawaya, B. The Role of Vpr in the Regulation of HIV-1 Gene Expression. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2626–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Cung, T.; Seiss, K.; Beamon, J.; Carrington, M.F.; Porter, L.C.; Burke, P.S.; Yang, Y.; et al. CD4+ T cells from elite controllers resist HIV-1 infection by selective upregulation of p21. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu XG, Lichterfeld M. Elite control of HIV: p21 (waf-1/cip-1) at its best. Cell Cycle. 3: 2011;10(19), 2011.

- Saez-Cirion, A.; Hamimi, C.; Bergamaschi, A.; David, A.; Versmisse, P.; Melard, A.; Boufassa, F.; Barre-Sinoussi, F.; Lambotte, O.; Rouzioux, C.; et al. Restriction of HIV-1 replication in macrophages and CD4+ T cells from HIV controllers. Blood 2011, 118, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chao, W.; Saini, M.; Potash, M.J. A Common Path to Innate Immunity to HIV-1 Induced by Toll-Like Receptor Ligands in Primary Human Macrophages. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e24193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Casuso, J.C.; Allouch, A.; David, A.; Lenzi, G.M.; Studdard, L.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Müller-Trutwin, M.; Kim, B.; Pancino, G.; Sáez-Cirión, A. p21 Restricts HIV-1 in Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells through the Reduction of Deoxynucleoside Triphosphate Biosynthesis and Regulation of SAMHD1 Antiviral Activity. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01324–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Crumpacker C. Personal communication & unpublished studies, 2018.

- Osei Kuffour E, Schott K, Jaguva Vasudevan AA, Holler J, Schulz WA, Lang PA, Lang KS, Kim B, Häussinger D, König R, Münk C. USP18 (UBP43) Abrogates p21-Mediated Inhibition of HIV-1. J Virol. 2018 Sep 26;92(20):e00592-18.

- Shi, B.; Sharifi, H.J.; DiGrigoli, S.; Kinnetz, M.; Mellon, K.; Hu, W.; de Noronha, C.M.C. Inhibition of HIV early replication by the p53 and its downstream gene p21. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, K.L.; Siegler, E.L.; Kenderian, S.S. CAR-T Cell Therapy: the Efficacy and Toxicity Balance. Curr. Hematol. Malign- Rep. 2023, 18, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M.; Raje, N. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma: can we do better? Leukemia 2020, 34, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzner, R.G.; Mackall, C.L. Tumor Antigen Escape from CAR T-cell Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, K.J.; Margossian, S.P.; Kernan, N.A.; Silverman, L.B.; Williams, D.A.; Shukla, N.; Kobos, R.; Forlenza, C.J.; Steinherz, P.; Prockop, S.; et al. Toxicity and response after CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy in pediatric/young adult relapsed/refractory B-ALL. Blood 2019, 134, 2361–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, A.V.; Turtle, C.J. Toxicities of CD19 CAR-T cell immunotherapy. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, S42–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenna, E.; Davydov, A.N.; Ladell, K.; McLaren, J.E.; Bonaiuti, P.; Metsger, M.; Ramsden, J.D.; Gilbert, S.C.; Lambe, T.; Price, D.A.; et al. CD4+ T Follicular Helper Cells in Human Tonsils and Blood Are Clonally Convergent but Divergent from Non-Tfh CD4+ Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 137–152.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, M.A.; Cyster, J.G. T follicular helper cells in germinal center B cell selection and lymphomagenesis. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 296, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Craft, J. T follicular helper cell heterogeneity: Time, space, and function. Immunol. Rev. 2019, 288, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621-63.

- Crotty, S. T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity 2019, 50, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesemann, D.R.; Portuguese, A.J.; Meyers, R.M.; Gallagher, M.P.; Cluff-Jones, K.; Magee, J.M.; Panchakshari, R.A.; Rodig, S.J.; Kepler, T.B.; Alt, F.W. Microbial colonization influences early B-lineage development in the gut lamina propria. Nature 2013, 501, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braams, M.; Pike-Overzet, K.; Staal, F.J.T. The recombinase activating genes: architects of immune diversity during lymphocyte development. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1210818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, P.C.; Monroe, J.G. Negative Selection of Immature B Cells by Receptor Editing or Deletion Is Determined by Site of Antigen Encounter. Immunity 1999, 10, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maës, J.; Caspi, Y.; Rougeon, F.; Haimovich, J.; Goodhardt, M. Secondary V(D)J Rearrangements and B Cell Receptor-Mediated Down-Regulation of Recombination Activating Gene-2 Expression in a Murine B Cell Line. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).