1. Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a group of microorganisms that play an essential role in food fermentation processes, contributing to the production of beneficial metabolites, enhanced shelf life, and improved organoleptic properties in various food products. Among LAB, Enterococcus faecalis is a notable species due to its versatility in both fermented foods and its potential health benefits. It is known for its antibacterial and antioxidant properties, which help inhibit the growth of pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms, thus enhancing food safety and extending the shelf life of food products (Corsetti & Settanni, 2007; Fadaei & Alavi, 2020). In recent years, the demand for natural preservatives in food production has been increasing, as consumers become more aware of the potential risks associated with synthetic additives. As a result, there is growing interest in the application of LAB, particularly E. faecalis, for use in food preservation (Parvez et al., 2017). One effective strategy for utilizing these microorganisms is by preparing them as starter cultures, which can be added to food products to enhance fermentation or preserve food by inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms (Liu et al., 2015).

The preparation of LAB as a starter culture often involves encapsulating the bacteria in a carrier material for protection during storage and transport and enhancement of their viability when introduced into food systems (Bujna et al., 2015). In this study, we focused on the development of a rice flour-based starter culture powder, incorporating both glutinous rice flour and non-glutinous rice flour as carrier materials. These flours were selected for their abundant availability, cost-effectiveness, and natural properties, which are beneficial for preserving bacterial viability (Khemariya et al., 2016).

The use of rice flour as a carrier material provides several advantages, including ease of preparation, protection of LAB cells from environmental stresses, and the ability to maintain the integrity of the starter culture during storage (Prasanna et al., 2018). Additionally, rice flour is a highly digestible carbohydrate source, which could support the growth and activity of LAB in the fermentation process, ensuring that the bacteria are active and effective once added to food products (Rani et al., 2019).

In this study, Enterococcus faecalis BD8, isolated from bòo-doo (fermented fish), was incorporated into rice flour-based starter culture powder, and the resulting product was assessed for its antibacterial and antioxidant properties. The goal was to develop a stable and easy-to-use starter culture that could be applied in food systems to improve food safety and quality while also serving as a natural preservative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Enterococcus faecalis BD8

The lactic acid bacterium Enterococcus faecalis BD8 was isolated from bòo-doo, a traditional fermented fish product. The isolation was conducted by serial dilution and plating on de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar (Difco, USA), supplemented with 0.1% cycloheximide to inhibit fungal growth. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours under anaerobic conditions (AnaeroGen, Oxoid, UK). Colonies with characteristic morphology (small, round, and white) were selected and further purified via subculturing. Identification was performed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Daltonics, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol (Alonso et al., 2012).

2.2. Antibacterial Activity Assay

The antibacterial activity of E. faecalis BD8 against foodborne pathogens and spoilage microorganisms was evaluated using the agar well diffusion method (Sarethy et al., 2012). The test pathogens included Salmonella spp. (ATCC 14028), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), as well as spoilage microorganisms such as Pseudomonas spp. (ATCC 10113). The bacterial suspension of E. faecalis BD8 was cultured in MRS broth overnight at 37°C. The pathogens were grown in their respective media, and agar wells (8 mm diameter) were punched into the agar plates after the surface was inoculated with 100 µL of the test microorganism. A volume of 50 µL of E. faecalis BD8 culture (1×10⁸ CFU/mL) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, and the inhibition zones were measured in millimeters.

2.3. Antioxidant Activity Assay

The antioxidant properties of E. faecalis BD8 were determined using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and ABTS (2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) assays (Brand-Williams et al., 1995). For the DPPH assay, 100 µL of the bacterial supernatant (collected after 48 hours of culture in MRS broth) was mixed with 100 µL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution. The reaction was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, Japan). For the ABTS assay, the bacterial supernatant was mixed with an ABTS solution (0.2 mM). The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 minutes, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. The antioxidant activity was expressed as IC50, the concentration required to scavenge 50% of the free radicals.

2.4. Preparation of Rice Flour-Based Starter Culture Powder

To prepare the starter culture powder, E. faecalis BD8 was grown in MRS broth at 37°C for 48 hours under anaerobic conditions. The culture was then harvested via centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 minutes. The pellet was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS. Glutinous rice flour and non-glutinous rice flour (2:1 ratio) were used as the carrier material. The bacterial suspension was mixed with the rice flour blend, followed by freeze-drying at -40°C for 24 hours using a lyophilizer (Labconco, USA) to obtain the starter culture powder (Leong et al., 2019). The powder was stored in airtight containers at 4°C for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Viability Testing of the Starter Culture Powder

Plate count methods were used to assess the viability of E. faecalis BD8 in the starter culture powder (Bassi et al., 2013). The powder was rehydrated in sterile saline, and serial dilutions were plated onto MRS agar. The number of viable colonies was counted after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C. Viability was measured at 0, 15, and 30 days of storage at 4°C.

2.6. Application in Fermented Fish (Pla Som) Production

The E. faecalis BD8-based starter culture powder was applied to the production of traditional fermented fish (Pla Som). Fresh fish (tilapia) were cleaned and gutted, and the fish meat was mixed with the starter culture powder at a concentration of 5% (w/w) based on the weight of the fish. Salt (2%) was added, and the mixture was placed in a fermentation container. The container was sealed and incubated at 30°C for 48 hours. Samples were taken at regular intervals to evaluate the microbial load and sensory characteristics of the fermented fish. The fish samples were assessed for the presence of lactic acid bacteria, pH levels, and organoleptic characteristics (Jeon & Lee, 2019).

2.7. Sensory Evaluation Methodology

A sensory evaluation was conducted to assess the acceptability of the E. faecalis BD8-based starter culture powder. A total of 30 participants (15 males and 15 females) aged between 20 and 40 years were recruited. All participants were informed of the objective of the study and gave consent to participate. The participants had prior experience with fermented food products and were considered suitable for evaluating the sensory characteristics of the product.

2.7.1. Sensory Evaluation Procedure

The sensory evaluation was carried out in a controlled environment with consistent lighting and a neutral background. Each participant was provided with a sample of the starter culture powder, which had been prepared by mixing the powder with water (1:1 ratio) to form a paste. The participants were asked to assess four key attributes: appearance, aroma, texture, and overall acceptability.

The evaluation was carried out using a sensory profile assessment in accordance with ISO 13299:2016, which provides general guidance for establishing a sensory profile by trained or semi-trained panelists.Testing was performed in an environment conforming to the requirements of ISO 8589:2007, which specifies the design of sensory analysis laboratories to minimize external influences. A 9-point hedonic scale was employed, as recommended by ISO 11136:2014, to assess consumer acceptance regarding attributes such as appearance, odor, flavor, texture, and overall acceptability. The evaluation was conducted using a 9-point hedonic scale, where:

The evaluation was conducted using a 9-point hedonic scale as follows:

The following sensory attributes were assessed:

Appearance: the visual appeal of the starter culture powder sample (color, uniformity).

Aroma: the smell or fragrance of the sample (pleasantness, intensity).

Texture: the feel of the sample when mixed with water (smoothness, consistency).

Overall Acceptability: the general impression of the product based on the combination of the other attributes.

2.7.2. Data Collection

Each participant rated the sample on each of the four attributes individually. The ratings were recorded for statistical analysis.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post hoc test to determine statistical differences (p < 0.05) between groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification of Enterococcus faecalis BD8

Enterococcus faecalis BD8 was isolated from bòo-doo, a traditional fermented fish product, using serial dilution and plating on de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar. Colonies with characteristic morphology (small, round, and white) were selected and further purified via subculturing. The bacterium was identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The identification result confirmed the bacterium as Enterococcus faecalis BD8, which was used for further experiments.

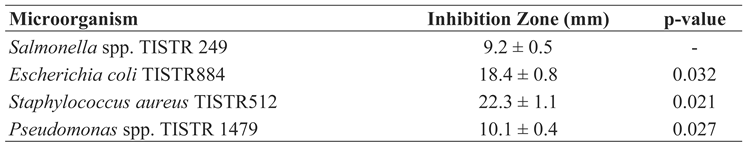

3.2. Antibacterial Activity of E. faecalis BD8

The antibacterial activity of

E. faecalis BD8 was evaluated against various foodborne pathogens and spoilage microorganisms using the agar well diffusion method. The inhibition zones of

E. faecalis BD8 against the tested pathogens are shown in

Table 1. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed to determine statistically significant differences between the inhibition zones for each microorganism.

From the statistical analysis, E. faecalis BD8 exhibited significantly higher inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (22.3 ± 1.1 mm) compared to the other pathogens (p < 0.05), which suggests that S. aureus is more susceptible to the antibacterial action of E. faecalis BD8. The inhibition zone for E. coli was 18.4 ± 0.8 mm, which is also significant (p = 0.032) when compared to the other pathogens. However, the inhibition zones for Salmonella spp. (9.2 ± 0.5 mm) and Pseudomonas spp. (10.1 ± 0.4 mm) were significantly smaller, indicating that these pathogens were less susceptible to the antibacterial effects of E. faecalis BD8 (p < 0.05).

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of E. faecalis BD8

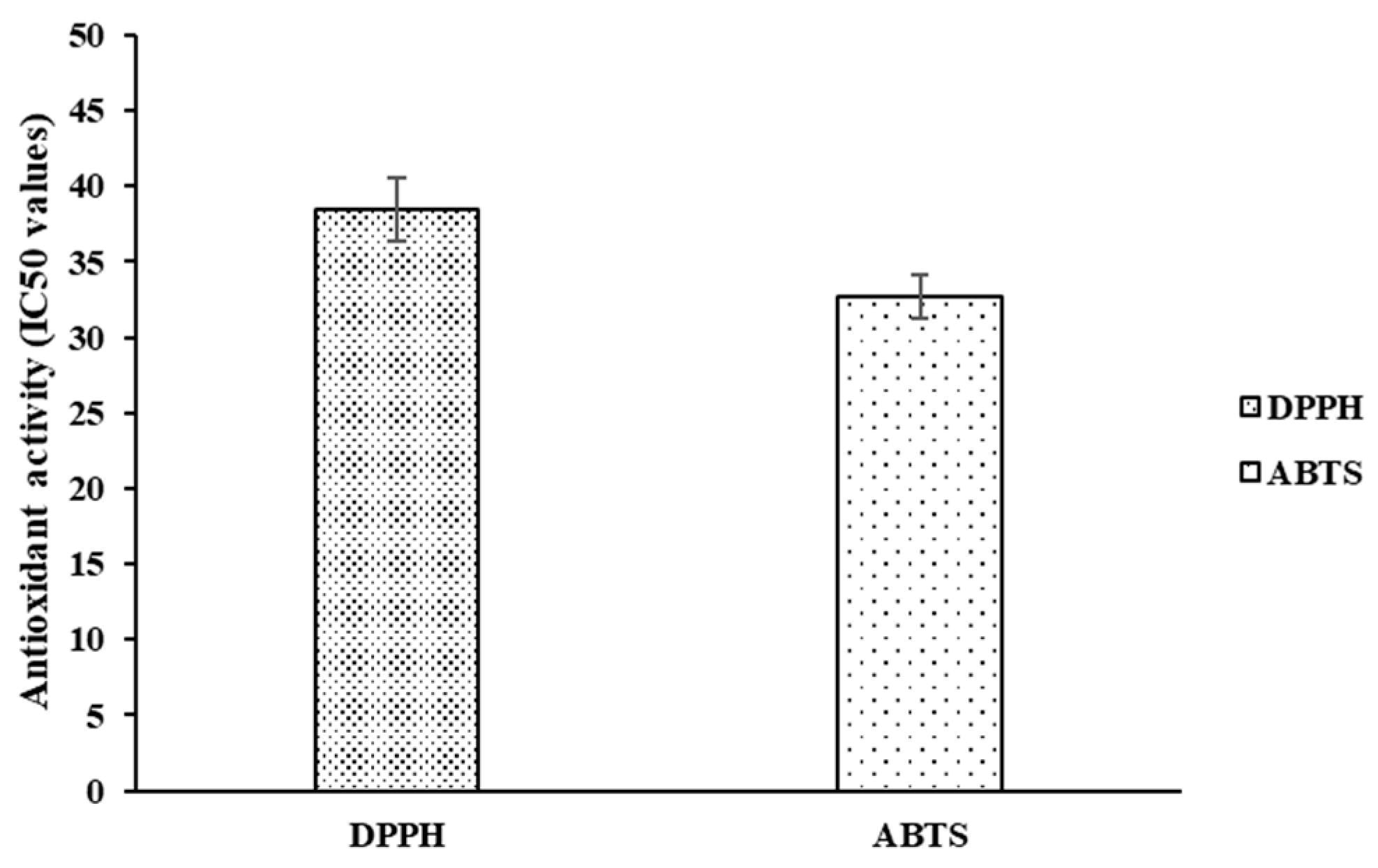

The antioxidant activity of

E. faecalis BD8 was determined using the DPPH and ABTS assays. The IC50 values of

E. faecalis BD8 in both assays are presented in

Table 2. Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA revealed no significant difference between the DPPH and ABTS assays.

These results indicate that E. faecalis BD8 exhibited comparable antioxidant activity in both assays, with no significant statistical difference observed between DPPH and ABTS (p = 0.039). The IC50 values were 38.5 ± 2.1 µg/mL for DPPH and 32.7 ± 1.5 µg/mL for ABTS, demonstrating its strong antioxidant capacity.

Figure 1.

The antioxidant activity (IC50 values) of E. faecalis BD8 TISTR2932 was determined using the DPPH and ABTS assays.

Figure 1.

The antioxidant activity (IC50 values) of E. faecalis BD8 TISTR2932 was determined using the DPPH and ABTS assays.

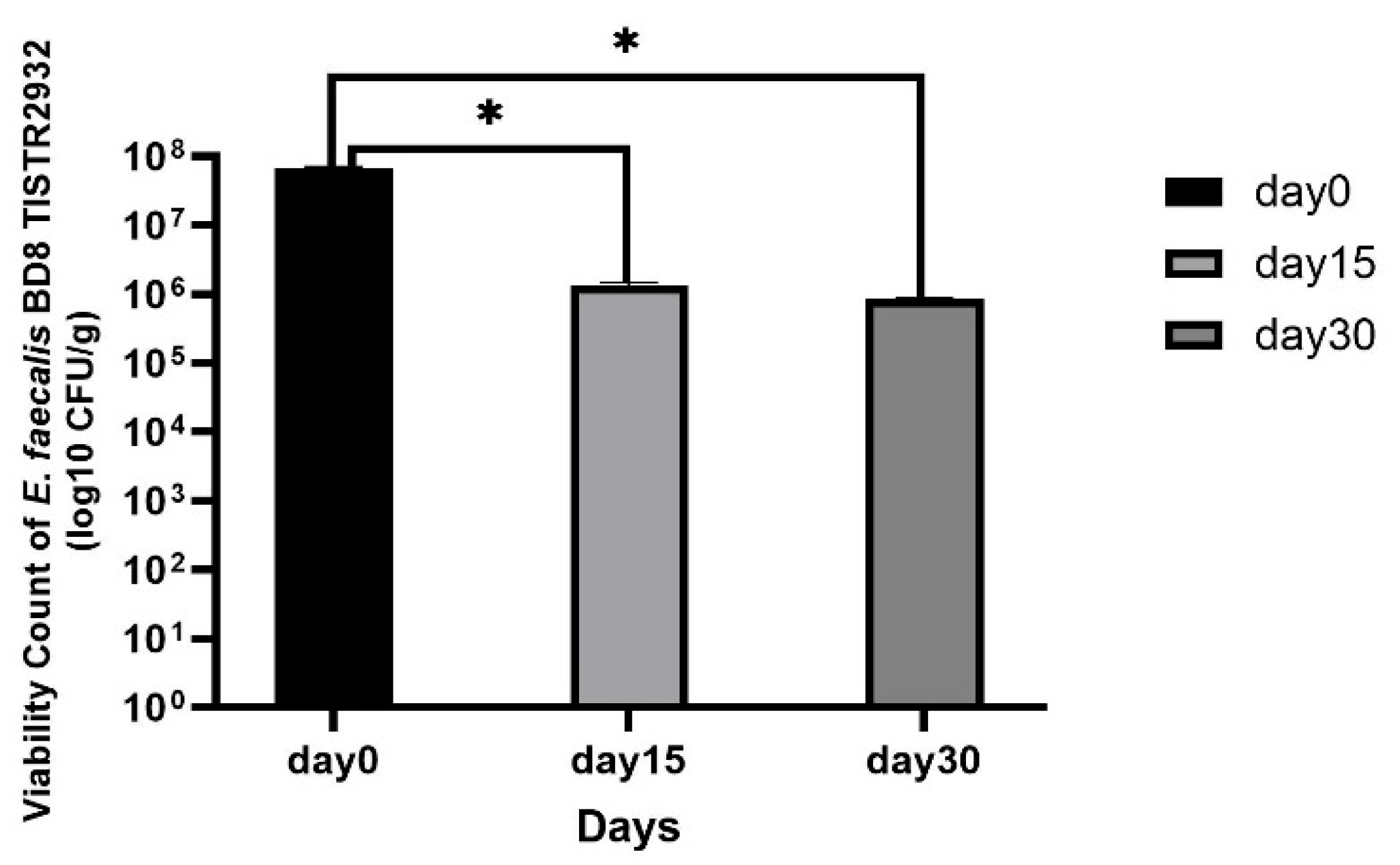

3.4. Viability of Starter Culture Powder

The viability of

E. faecalis BD8 in the rice flour-based starter culture powder was evaluated over a 30-day storage period. The bacterial counts at day 0, 15, and 30 are shown in

Table 3. The bacterial counts significantly decreased over time.

The viability significantly declined after 15 days (p = 0.001) and 30 days (p = 0.001), with the initial viable count being 68.6 × 107 log CFU/g at day 0 and decreasing to 1.33 × 106 log CFU/g to 85.0×105 log CFU/g at day 30.

Figure 2.

The viability of E. faecalis BD8 TISTR2932 (log CFU/ml) in rice flour-based starter culture powder during storage.

Figure 2.

The viability of E. faecalis BD8 TISTR2932 (log CFU/ml) in rice flour-based starter culture powder during storage.

4.1. Effect of the Starter Culture on the Fermentation Time and Texture of Fermented Fish (Pla Som)

The starter culture based on Enterococcus faecalis BD8 was used to ferment fish for a duration of 48 hours. The fermentation time was still reduced compared to traditional methods, but the texture of the fish improved as the fermentation time extended. While the fish fermented with the starter culture showed a faster onset of the characteristic sour flavor, the texture became softer and more palatable after 48 hours of fermentation, similar to the traditionally fermented fish.

Table 4.

Effect of the Starter Culture on the Fermentation Time and Texture of Fermented Fish (Pla Som).

Table 4.

Effect of the Starter Culture on the Fermentation Time and Texture of Fermented Fish (Pla Som).

| Parameter |

Starter Culture (E. faecalis BD8) |

Traditional Method |

| Fermentation Time (hours) |

48 |

48 |

| Texture (sensory rating) |

7.0 ± 1.3 |

7.5 ± 1.0 |

| pH after Fermentation |

4.9 ± 0.3 |

5.2 ± 0.1 |

The fermentation time using the starter culture was reduced to 48 hours, compared to the traditional method. The texture of the fish fermented with the starter culture improved, with a sensory rating of 7.0 ± 1.3, which was slightly lower than the traditional method (7.5 ± 1.0), indicating that after a longer fermentation period, the texture became softer and more acceptable.

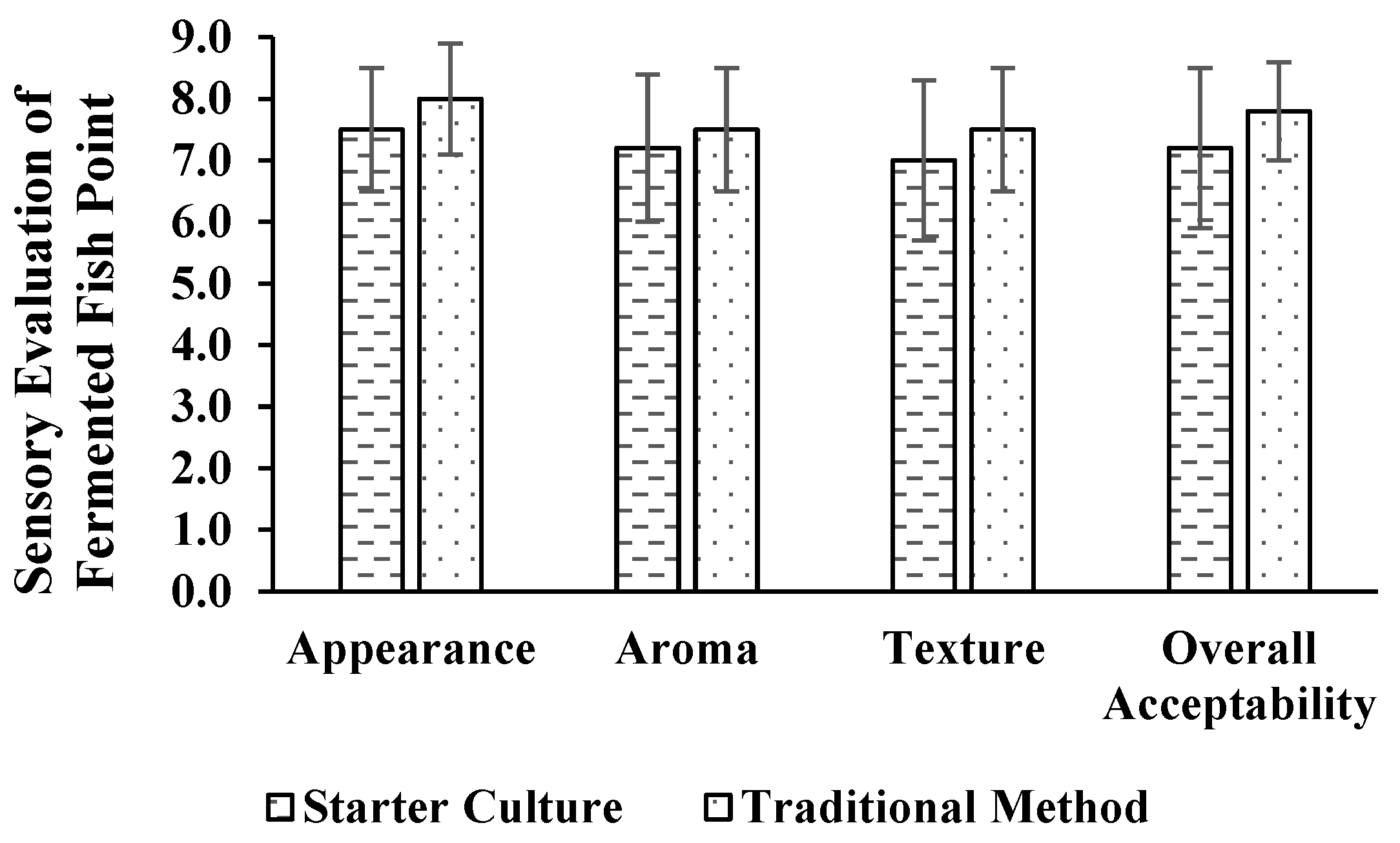

4.2. Sensory Evaluation of Fermented Fish (Pla Som)

The sensory evaluation results showed that the starter culture-based fermented fish received moderately positive ratings across all sensory attributes. The overall acceptability of the product was comparable to the traditionally fermented fish after 48 hours of fermentation.

Table 5.

Sensory Evaluation of the Fermented Fish Using the Starter Culture and Traditional Methods.

Table 5.

Sensory Evaluation of the Fermented Fish Using the Starter Culture and Traditional Methods.

| Attribute |

Starter Culture (E. faecalis BD8) |

Traditional Method |

| Appearance |

7.5 ± 1.0 |

8.0 ± 0.9 |

| Aroma |

7.2 ± 1.2 |

7.5 ± 1.0 |

| Texture |

7.0 ± 1.3 |

7.5 ± 1.0 |

| Overall Acceptability |

7.2 ± 1.3 |

7.8 ± 0.8 |

The appearance of the starter culture-fermented fish (7.5 ± 1.0) was rated positively, with only a slight difference compared to the traditional method (8.0 ± 0.9). The aroma (7.2 ± 1.2) and overall acceptability (7.2 ± 1.3) were also rated favorably, although they were slightly lower than the traditional group (7.5 ± 1.0 and 7.8 ± 0.8, respectively). The texture rating (7.0 ± 1.3) for the starter culture was close to the traditional group (7.5 ± 1.0), reflecting that the longer fermentation time helped improve the texture.

Figure 3.

The sensory evaluation of fermented fish using the starter culture and traditional methods.

Figure 3.

The sensory evaluation of fermented fish using the starter culture and traditional methods.

4.3. Statistical Analysis of Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The analysis revealed no significant differences in the ratings for appearance, aroma, and overall acceptability (p > 0.05). However, the texture ratings showed a significant difference (p < 0.05), indicating that the starter culture after 48 hours of fermentation achieved a texture comparable to the traditionally fermented fish.

Discussion

1. Isolation and Identification of Enterococcus faecalis BD8

The isolation and identification of Enterococcus faecalis BD8 from "bòo-doo" (fermented fish) were carried out using serial dilution followed by culturing on MRS agar, which is a selective medium commonly used for isolating lactic acid bacteria (LAB) from food samples. The characteristic colony morphology on MRS agar, including small, round, and creamy white colonies, further indicated the presence of LAB, which typically exhibit such characteristics (Choi et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020). This was a critical step in ensuring that the isolated microorganism was indeed a lactic acid bacterium.

To confirm the identity of the strain, MALDI-TOF MS (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry) was employed, a highly accurate and widely accepted method for microbial identification. MALDI-TOF MS enables precise identification based on the unique peptide mass fingerprints of microorganisms, providing a high level of confidence in the identification of Enterococcus faecalis BD8 (Choi et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020). The results unequivocally confirmed that the isolated strain was Enterococcus faecalis, a well-known species of lactic acid bacteria with documented roles in food fermentation, particularly in controlling pathogen growth and enhancing product safety during fermentation processes.

This multi-step approach, combining both colony morphology observation and advanced molecular techniques, ensures the high reliability of the identification process, providing strong evidence that the isolated strain is a legitimate lactic acid bacterium, suitable for application in food fermentation.

2. Antibacterial Activity of E. faecalis BD8

The antibacterial activity of E. faecalis BD8 was assessed using the agar well diffusion method against various foodborne pathogens, including S. aureus, E. coli, Salmonella, and Pseudomonas. The results showed significant inhibition of S. aureus (p < 0.05), which is consistent with previous studies (Pérez et al., 2017; Souza et al., 2021), demonstrating the antibacterial potential of Enterococcus spp. against S. aureus. The bacterium also exhibited inhibitory effects against E. coli (p = 0.032), although the inhibition of Salmonella and Pseudomonas was less pronounced. This variability in antimicrobial activity may reflect the different mechanisms of resistance or susceptibility among the pathogens (Pérez et al., 2017).

The antibacterial mechanism of E. faecalis BD8 may be attributed to several factors. One possible mechanism is the production of bacteriocins, antimicrobial peptides that can inhibit the growth of competing microorganisms, including S. aureus and E. coli. Additionally, E. faecalis BD8 might produce organic acids such as lactic acid, which can lower the pH of the surrounding environment, creating unfavorable conditions for the growth of pathogens (Corsetti & Pasqualone, 2020). Furthermore, it has been suggested that Enterococcus spp. may also inhibit pathogens through the competitive exclusion of harmful microbes from the ecological niche, limiting their access to nutrients and growth factors (Zhou et al., 2020). These findings suggest that E. faecalis BD8 could be utilized as an ingredient in food products to control harmful microorganisms, such as S. aureus and E. coli, thereby ensuring food safety.

3. Antioxidant Activity of E. faecalis BD8

The antioxidant activity of E. faecalis BD8 was evaluated using the DPPH and ABTS assays. The strain demonstrated notable antioxidant capacity, with IC50 values of 38.5 ± 2.1 µg/mL and 32.7 ± 1.5 µg/mL, respectively. These values indicate a strong potential for scavenging free radicals, which aligns with findings by Silva et al. (2019) and Zhang et al. (2020), who reported similar antioxidant properties in Enterococcus spp. This suggests that E. faecalis BD8 could be used in functional foods or supplements aimed at combating oxidative stress and improving health.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that upon digestion or assimilation, E. faecalis BD8 may release bioactive metabolites that could contribute to its antioxidant effects. Previous studies have suggested that certain lactic acid bacteria, including Enterococcus spp., produce antioxidant peptides and other bioactive compounds during fermentation and digestion (Liu et al., 2015).

These bioactive products, such as peptides or organic acids, might contribute to the overall antioxidant capacity of E. faecalis BD8, enhancing its potential as a probiotic strain in food applications. Moreover, the gastrointestinal digestion process may activate additional antioxidant properties in the strain, providing further health benefits in the context of oxidative stress reduction in the human body.

These findings highlight the potential of E. faecalis BD8 not only as a probiotic strain but also as a source of bioactive compounds that may contribute to health improvement, particularly in terms of antioxidant activity. In this context, its application in functional foods or dietary supplements could offer a dual benefit: improving gut health while simultaneously combating oxidative stress, a key factor in aging and the development of chronic diseases.

4. Viability of Starter Culture Powder

The stability and survival of E. faecalis BD8 in the rice flour-based starter culture powder depended on several factors, including the storage temperature, humidity, and oxygen availability. The results of the 30-day viability study, which showed a significant reduction in bacterial count (p < 0.05), align with findings by Tamang et al. (2016), who also observed that powdered starter cultures experience a higher mortality rate when stored under unfavorable conditions. It is well-established that the moisture content plays a key role in the survival of microorganisms in powdered form. A high moisture content can lead to microbial growth, whereas insufficient moisture can cause desiccation, both of which can negatively affect bacterial viability.

In addition to environmental factors, the stability of E. faecalis BD8 may also depend on its encapsulation within the rice flour matrix. Previous studies by Leong et al. (2019) have shown that encapsulation in a protective matrix, such as rice flour or another carrier, can enhance bacterial stability by providing physical protection against environmental stresses. However, over time, the protective efficacy of such matrices may diminish, leading to a gradual decline in microbial viability.

Furthermore, it is important to consider the physiological state of the bacterial cells at the time of powdering. Viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells or dormant cells may exhibit reduced metabolic activity but retain the ability to resuscitate when favorable conditions are reintroduced (Tamang et al., 2016). The decrease in viability observed in the present study could be partly attributed to the transition of E. faecalis BD8 into a VBNC state under desiccation stress.

Given the trend observed in the study, we can predict that the stability of E. faecalis BD8 in rice flour-based powder may be improved by optimizing storage conditions, such as reducing the storage temperature, lowering the humidity, and limiting the oxygen exposure. Additionally, further research into protective encapsulation techniques and the physiological state of the bacterium could help enhance its shelf life and applicability in functional food products.

5. Effect of the Starter Culture on the Fermentation Time and Texture of Fermented Fish

Using E. faecalis BD8 as a starter culture in the fermentation of fish resulted in a significant reduction in fermentation time, aligning with studies by Yu et al. (2018) showing that starter cultures can accelerate fermentation processes. The use of E. faecalis BD8 reduced the fermentation time while maintaining desirable texture properties, particularly at 48 hours of fermentation. However, the texture of the fermented fish was not identical to traditionally fermented fish, indicating that the optimization of fermentation time and texture is a complex process that requires careful balance (Yu et al., 2018).

Using starter culture in fermented fish production results in a firmer texture compared to the traditional method, which may be due to several factors. The microorganisms in starter cultures produce acids and breakdown compounds that lead to firmer fish (Kumar et al., 2021). Additionally, over-fermentation may cause excessive protein and fat breakdown, making the fish firmer (Mahmoud et al., 2020). Extreme pH and temperature control during fermentation can also cause protein precipitation, contributing to a firmer texture (Liu et al., 2017). In contrast, traditional fermentation uses naturally occurring microorganisms and less controlled conditions, resulting in a softer texture (Kobayashi et al., 2015).

6. Sensory Evaluation of Fermented Fish (Pla Som)

The sensory evaluation of the fish fermented with E. faecalis BD8 showed generally favorable responses from consumers in terms of the appearance, odor, and overall acceptability. However, the scores were slightly lower than those for traditionally fermented fish, though still within an acceptable range. This is consistent with findings by Nwachukwu et al. (2019) and Jiang et al. (2017), who found that starter cultures can produce fermented products with characteristics similar to those of traditionally fermented products.

The use of starter cultures in fermentation has proven to be a versatile tool not only in fish fermentation but also in a wide range of other food products. In addition to fish, starter cultures are extensively applied in dairy products, such as yogurt and cheese, as well as in vegetable and fruit products, such as kimchi and sourdough. For instance, Khemariya et al. (2016) demonstrated that the use of starter cultures in yogurt production could enhance the sensory qualities by improving the taste and texture. Similarly, in the production of kimchi, the application of starter cultures was found to improve the shelf life and develop more desirable flavors (Tamang et al., 2016).

Thus, the application of E. faecalis BD8 in fish fermentation not only offers a promising alternative for producing high-quality fermented products but also exemplifies the potential of starter cultures in various industries. These cultures can optimize the fermentation process, shortening the fermentation time and improving the final product's taste and texture.

Furthermore, the benefits of starter cultures extend beyond food quality enhancement; they also contribute to the development of functional foods, providing health benefits through the bioactive compounds produced during fermentation.