1. Introduction

Since ancient times, crowdsourcing information has been vital for obtaining data for various calculations (Abraham et al. 2024). Stravon mentioned the importance of the latter especially when there are no scientific measurements (i.e., in the absence of instrumental measurements) (Stravon, Geografika, Book B, Mathematical Geography). How many times did the ancient geographers rely on travellers for calculating distances? The answer is really many times. In ancient manuscripts we find that Eratosthenes was mentioning crowdsourcing information obtained by travellers or other people. (Geografika, Book B, Mathematical Geography). In any time period we live in, crowdsourcing contributes to many disciplines as crowdsourced information is instantly reported, contributed, captured and rapidly shared. We could dare to associate the information shared by people in ancient times with the information that is shared nowadays through social media. From a geographical perspective, social media data can be treated as an unconventional source of volunteered geographical information (VGI) (Goodchild 2007) in which the social media users share content, thus unintentionally contributing to related disciplines.

Even with the best of the computer-based measurements of our times though, the fact that billions of people are equipped with a mobile with a very wide range of technological capabilities and the fact that billions of posts are generated daily, social media emerge as a source that cannot be ignored (Abraham et al. 2024; Soomro et al. 2024; Du et al. 2025).

On the other hand, it is widely known that the management of environmental problems is a global concern today. Climate change affects us all, and as a result a lot of related initiatives have been added to our lives. The majority of researchers nowadays relate the increase of floods and hydrological hazards to the climatic change (Hirabayashi et al. 2021; Wasko et al. 2021).

As a result, disaster management of hydrological hazards is vital for preventing, mitigating and responding to natural disaster events. Recent technological tools that are utilized in disaster management DM tasks are imagery, drones and social media (Daud et al. 2022; Iqbal et al. 2023).

Specifically regarding the latter in hydrological hazard management, the challenges of manipulating social media data are numerous (Guo et al. 2025). Some of the most significant include the following cases: sharing incomplete information (Abraham et al. 2024); repeating information (Feng et al. 2020); the enormous volume of information (Abraham et al. 2024) produced rapidly (Chen et al. 2023); fake news (Aïmeur et al. 2023; Feng et al. 2020), although these issues are mostly reported in fields of controversial areas, like politics (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017) and not in topics regarding natural disasters and their actual consequences. With regard to floods, social media data are considered an especially effective alternative or a source of added value since survey operations and imagery of high accuracy are costly and software-based solutions are input-dependent (Guo et al. 2025). Generative artificial intelligence (GAI) is expected to worsen the related issues, especially in terms of generating scenario-based flood images.

While some automatically generated metadata of a post are precise enough (i.e a timestamp, embedded geographic coordinates), more generally there is a high level of ambiguity in social media posts as the time and place of the post do not necessarily reflect the actual time and place of the photo (Gao et al. 2011; Feng et al. 2020). Moreover, posts consisting of text, photos, videos or combinations of those are considered in many cases subjective and inaccurate or erroneous (Feng et al. 2020; Abraham et al. 2024; Soomro et al. 2024). Even in natural disasters there are no reports of fake news incidents—at least not intentional—and until the early weeks of 2025, the credibility of social media information, which is a general topic, and the effective manipulation of fake news, which is a special subtopic, are emerging in social media in general, especially with regard to the latter, when there are controversial topics (Petratos and Faccia 2023). There are some initial steps towards defining misinformation in risk response of disaster management, mostly at a qualitative level (Omar and Belle 2024) and various other deep learning-based approaches (Zair et al. 2022). Having different data modalities is a very significant capability, as they can lead to extracting significant in situ information that would not otherwise be tracked, especially when field inspection is not always an option as it requires budget and personnel. And even in those cases where it is possible, rapid field inspection is often a utopian dream (Kanth et al. 2022). Considering all of the above also in relation to the climatic change, social media have emerged as valuable ways of communicating, disseminating news, information, opinions, emotions and other comments suitable for appropriate hydrological management.

A method for measuring the credibility of social media content is similar to the notion of Linus’s Law (Haklay et al. 2010). As in open source computer software, the more programmers the fewer the bugs in the end (Schweik et al. 2008), in social media, when reporting on something really obvious—for example, the appearance of a natural disaster event—the more people mentioning the related information, the more credible the related information is.

Even if the instrumental measurements are more precise and credible, the contribution of social media can be considered, in many cases, invaluable as it can provide information that cannot be captured from satellites, such as instructions from authorities, details about missing people, humanitarian aid, emotional advice, particulars about provision, about planning, even in situ information: e.g., ‘how the clouds look from where I am’, or other comments from local experience comparing, for instance, the current natural event to those of previous times.

There is a lot of research which assesses the contribution of social media to hydrological matters (Section Related Work). In recent years, there is no doubt that there is a tendency for more AI-based approaches (Abraham et al. 2024), which can deal with the enormous volume of the information produced.

Current research presents a methodological framework within the described framework for extracting crowdsourced hydrological information from a mash-up of social media datasets and of different modalities and specifically, text strings, images and videos collected by using hashtags and keywords regarding the Ianos medicane (Mediterranean, Greek territory, September 2020) from several social media platforms. Moreover, recent trends in AI have been utilized: a comparison of Long Short Term Memory—Recurrent Neural Networks (LSTM-RNN) and transformers for text classification; an ensemble method of location entity recognition (LER) and conventional geoparsing; and an ensemble method among a fine-tuned VGG-19, ResNet101 and EfficientNet for photo classification. The same ensemble method was used for classifying video frames which were sequentially used for estimating a new index: the Relevant Share Video Index (RSVI), which provides an insight into the extent to which a video contains relevant photo images.

The next sections of the paper present indicative related work (Section Related Work), and sequentially provide a description of the medicane Ianos (

Section 2) and information about the Data and Material Used (Section Data and Material Used). The analytic description of the methodology is in

Section 3, while the next

Section 4 is related to Results and Discussion. Finally

Section 5 completes the research paper with a conclusion.

Related Work

In the international literature, there is a variety of definitions of what can be called a ‘mash-up’ according, apparently, to the field of origin of the researchers. He and Zha (2013) used previously published definitions: ‘easy, fast integration, frequently made possible by access to open APIs and data sources to produce results beyond the predictions of the data owners’ (de Vrieze et al. 2010; Bader et al. 2012).

The definition by He and Zha (2013) is specific to the social media mash-up as a ‘special type of mash-up application that relies on various open APIs and feeds to combine publicly available content from different social media sites to create valuable information and build useful new applications or services’. Inevitably a lot of research associates mash-ups with services (Hummer et al. 2010, Chen and Peng 2012). Apart from services, the term ’mash-ups’ is apparently applied to a variety of cases: among others, we find data mash-ups (Jarrar and Dikaiakos 2009; Fung et al. 2011) and the mash-up of techniques or methods (Fuller 2010; Nakamura et al. 2016) etc.

A general definition of the term mash-up could be ‘Any complementary, simultaneous use of different elements, either datasets, services, methods, or approaches, which produce a result that could not be produced by relying on the used elements individually”. Despite the lack of a precise definition, the importance of mash-ups, in a sense of combining sources, services, techniques, approaches, in crisis situations caused by hydrological disasters is significant.

The effectiveness of social media mash-ups has emerged, among others, in Schulz and Paulheim (2013) who assessed them as a ‘helpful way to provide information to the command staff’. Decision-makers can also benefit. The same authors referred to the significance of social media sources in various cases, including among others the Red River Floods (April 2009, USA). By assessing various other disastrous events, e.g., earthquakes, they concluded that crowds can be used for rapid mapping. A few years later, in 2015, the Copernicus ecosystem (source:

https://mapping.emergency.copernicus.eu/) initiated the rapid emergency mapping service, which has been providing valuable insights extracted through the automatic analysis of imagery data.

With regard to hydrological disaster events and data processing, the topic of effective photo classification of such events has been researched in recent years (Ning et al. 2020; Pereira et al. 2020; Romanascu et al. 2020; Kanth et al. 2022). As AI-related solutions are emerging, it is really obvious that those solutions would be assessed in order to confront with various time-consuming and complicated tasks of the field.

A varied performance is demonstrated in the international literature regarding classification tasks, ranging from a low to mid performance of the models (Ridwan et al. 2022; Delimayanti et al. 2020) up to more effective solutions, which receive SOTA metrics of above 90% (Ponce-Lopez and Spataru 2022). This is quite logical as there are many different factors that affect the actual SOTA evaluation metric.

Sheth et al. (2024) presented an ensemble method technique based on InceptionV3 and CNN, achieving an accuracy rate of more than 92%. They applied their approach to the CWFE-DB database, containing photos of Cyclones, Wildfires, Floods and Earthquakes. Compared to CNN only, the ensemble technique received a better score in SOTA metrics.

Moreover, Jackson et al. (2023) assessed the performance of 11 models in terms of their ability to classify photos as flood-related and not flood-related. The dataset used was FloodNet. The dataset provides Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) images, so it might not be so relevant to social media-posted photos. However, even though they are not the majority, similar photos are frequently posted on social media.

Pally and Samadi (2022) assessed the performance of a CNN model, developed by them, for flood image classification and object-detection models for object detection in flood-related images, including Fast R-CNN and YOLOv3. One conclusion, among others, is the very varying performance of different algorithms on different objects of the same dataset.

Soomro et al. (2024) assessed the effectiveness of X, formely Twitter, when contributing to flood management. They emphasized on the emotional and public opinion perspective available through X for hydrological management. They processed all the related tweets of the Pakistan floods of 2022 in Karachi. They scored the sentiment of each tweet based on a lexicon-based sentiment assessment approach.

They assessed the Twitter findings along with output from other sources, characterizing social media data and Twitter as crucial for resilience, the sharing of information and the adaptation of the announcements of the public authority.

Kanth et al. (2022) presented a deep learning approach for flood mapping based on social media data. They classified text and photos with an accuracy of 98% for a pretrained and fine-tuned Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and a range of 75–81% accuracy from various deep learning models for photo classification. They assessed their approach on three different flood events: the floods in Chennai 2015; Kerala 2018; and Pune 2019. They initially classified the texts as I. Related to floods and II. Not related to floods and then the ‘flood texts’ were further processed along with their corresponding images and classified into three main categories: I. No flood; II. Mild; and III. Severe. They assessed various machine learning models: SVM, ANN, CNN, Bi-LSTM and BERT for text classification and ResNet, VGG16, Inception V3 and Inception V4 for photo classification.

Moreover, Du et al. (2025) presented CA-Resnet, an approach based on Resnet with an addition of Coordinate Attention on it, for identifying water-depth estimation from social media data. They tested their approach on a flood dataset of photos posted on social media regarding the 2021 Henan rainstorm in China, which consisted eventually of 5676 images. Their approach, in comparison to the conventional VGGNet, ResNet, GoogleNet and EfficientNet had a slightly better performance measured by the F1, Precision, Recall, and MAE, while their approach was outperformed slightly by another model only with regard to Accuracy. In their research, social media datasets emerge as a valuable source for obtaining water-depth data from different modalities at zero cost.

The water level as a matter of classification was also formulated in Feng et al. (2020). Their approach included initially classifying images posted through social media, as ‘related’ and ‘not related’ to flood, while the related ones with the presence of people were further processed in order to classify the water level in respect to various parts of the human body that were submerged in the flooded water. As a case study they used Hurricane Harvey (2017). They used the DIRSM dataset extended by photos from other sources and consisted of 19,570 features. In general, their approach consisted of using various models, had little better precision and average precision scores calculated in cut-offs in comparison to previous approaches that had been applied during the MediaEval ’17 workshop. With regard to the estimation of water levels, the overall accuracy of their approach has impressively better metrics (overall accuracy of 89.2%), while by fusing their model with that of another method they achieved an overall accuracy of 90%. Finally they mapped the flooded area, by extracting the location of social media, and by using census administrative areas. They also manipulated the data with other sources, like remote sensing. By combining social media and remote sensing there was an increasing accuracy. One of the noted assumptions of combining remote sensing and social media is that the latter can contribute to identifying the severity of an event at an earlier time point.

Guo et al. (2025) assessed the contribution of social media to flood-related disasters by analysing posts from 2016 up to 2024 regarding urban flooding in Changsha, a city in South Central China, which is affected by flood events resulting from, among other factors, rapid urbanization, heavy rainfall, low topography and the Xiangjiang river. Their approach includes methods for extracting information from text and photos. Related information included flood locations and water depths. They also found positive correlation among the volume of the generated posts and various indicators, including population and seasonal rainfall. They performed the analysis within a prisma of a short-term and a long-term calendar time periods. During the first period, the posted information mostly relates to the response, while during the second period, the posts are concerned with prevention and governmental responsibilities. Yolo v5 was used for extracting information from photos. Other research is also available that deals with, among others, the potential of social media to contribute to identifying urban waterlogging (Chen et al. 2023).

2. Case Study: Medicane Ianos

Ianos was as a barometric low with tropical characteristics (source: National Observatory of Athens (NOA); meteo.gr). While the actual medicane formulation started on September 17 (Lagouvardos et al. 2020; Lagouvardos et al. 2022), the cyclone was formed as a surface cyclone in the Gulf of Sidra on September 15, while its original development started even earlier, somewhere during September 11–12. Its trajectory was from the north coast of Africa, in Libya, towards the north. During September 16, the medicane was located between Sicily and Greece, and thus affected the Greek territory from September 17, the date that is was formed as a medicane (Lagouvardos et al. 2022), to September 19 with an inverted u trajectory from the Ionian Sea to the south of Crete, ending its 1900 km journey on the Egyptian coast during September 20. Sea surface temperature (SST) was more than 28 °C in the Gulf of Sidra while along the route of the medicane the SST has a range of more than 2 °C (Lagouvardos et al. 2022).

The rainfall in some cases was more than 300 mm (Pertouli, West Thessaly, Greece; source: NOA and meteo.gr), and more than 350 mm (Cephalonia island, NOA), while in West Greece in general the daily accumulated rainfall was over 600 mm. The minimum sea level pressure (SLP) was 984.3 hPa, recorded in Palliki, Cephalonia, while the station in Zante recorded 989.1 hPa, and a mean wind speed of 30 m s−1, with wind gusts reaching a maximum of 54 m s−1.

Among the consequences of the medicane were numerous landslides, flooding and precipitation. Lagouvardos et al. (2022) identified more than 1400 landslides caused in two days. Four casualties and damage to numerous properties and infrastructure composed a disastrous landscape.

The medicane was named by the NOA. Other names referred to in various sources include Cassilda, Udine and Tulpar. Ianos was the fourth medicane since 2016, after medicane Trixie, Medicane Numa (November 2017) and Medicane Zorbas (September 2018) (Lagouvardos et al. 2022).

Data and Material Used

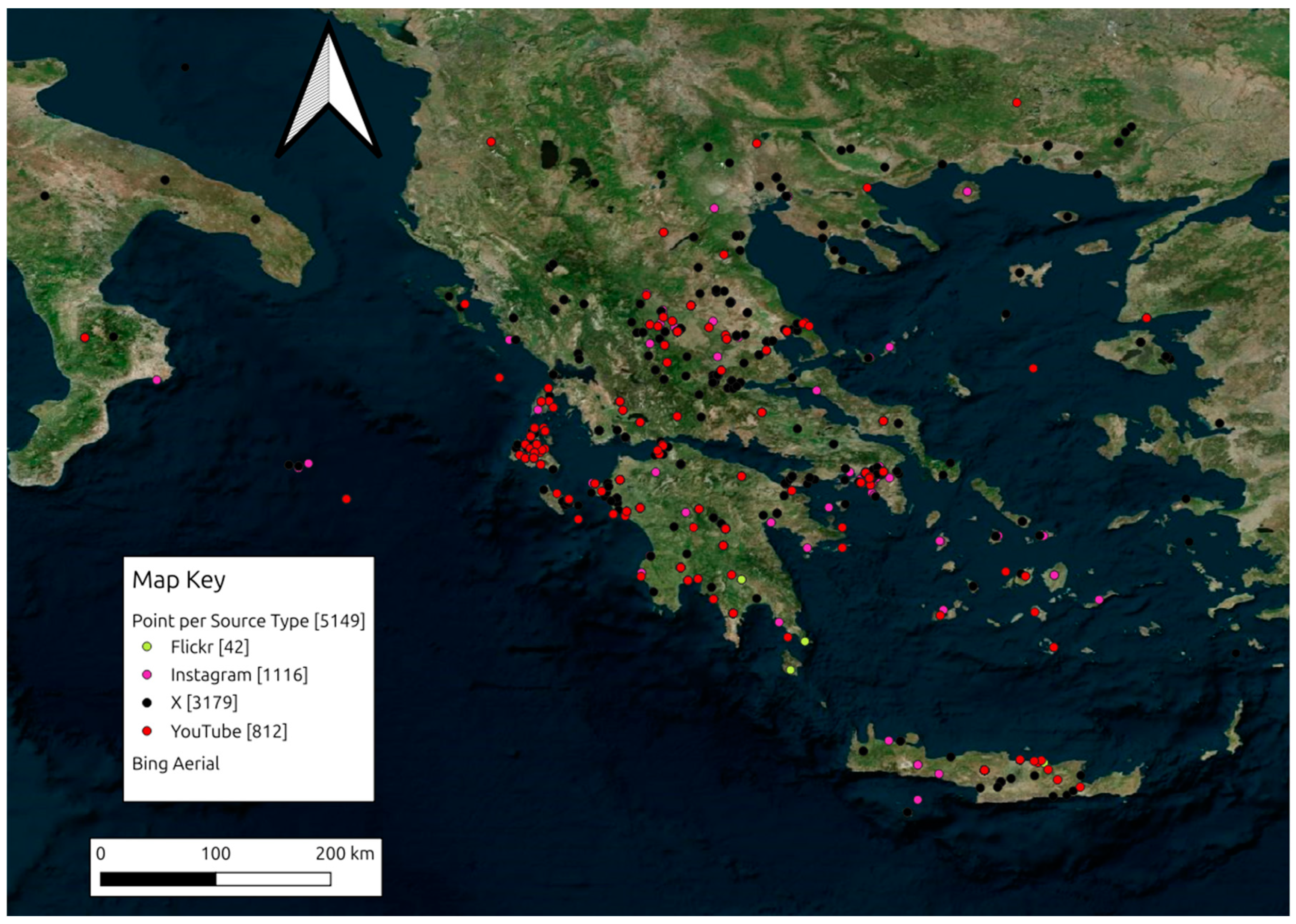

The author created and analyzed a mash-up consisting of the following datasets:

An Instagram dataset scraped during 2020 (Arapostathis, 2020), which, after processing, consisted of 241 videos and 1414 photos and related text strings, posted from 12 September up to 21 September 2020.

An X dataset, consisting of 4867 tweets, scraped during July 2024, using the application twibot v 1.4.6 and posted from 12 September 2020 up to 30 October 2020.

A Flickr dataset, consisting of 1535 photos with their related metadata which included timestamps, captions, IDs. The Flickr dataset was collected by using the official Flickr Application Programmable Interface (API), posted from 12 September up to 30 October 2020.

A YouTube dataset consisting of 512 videos and their related titles, descriptions and timestamps by employing the official API collected using the keywords: ‘medicane Ianos’ in Greek (κυκλώνας Ιανός) and English.

The Deucalion dataset (Arapostathis 2024) used for fine-tuning VGG-19, ResNet101 and EfficientNet.

The main language used in the current research was Python. Indicative libraries used were, among others, the torch, transformers, torchvision, gr-nlp-toolkit, ultralytics and pandas. LibreOffice and Quantum GIS were used for quality checks and for developing the final figures and maps, respectively.

3. Methodology

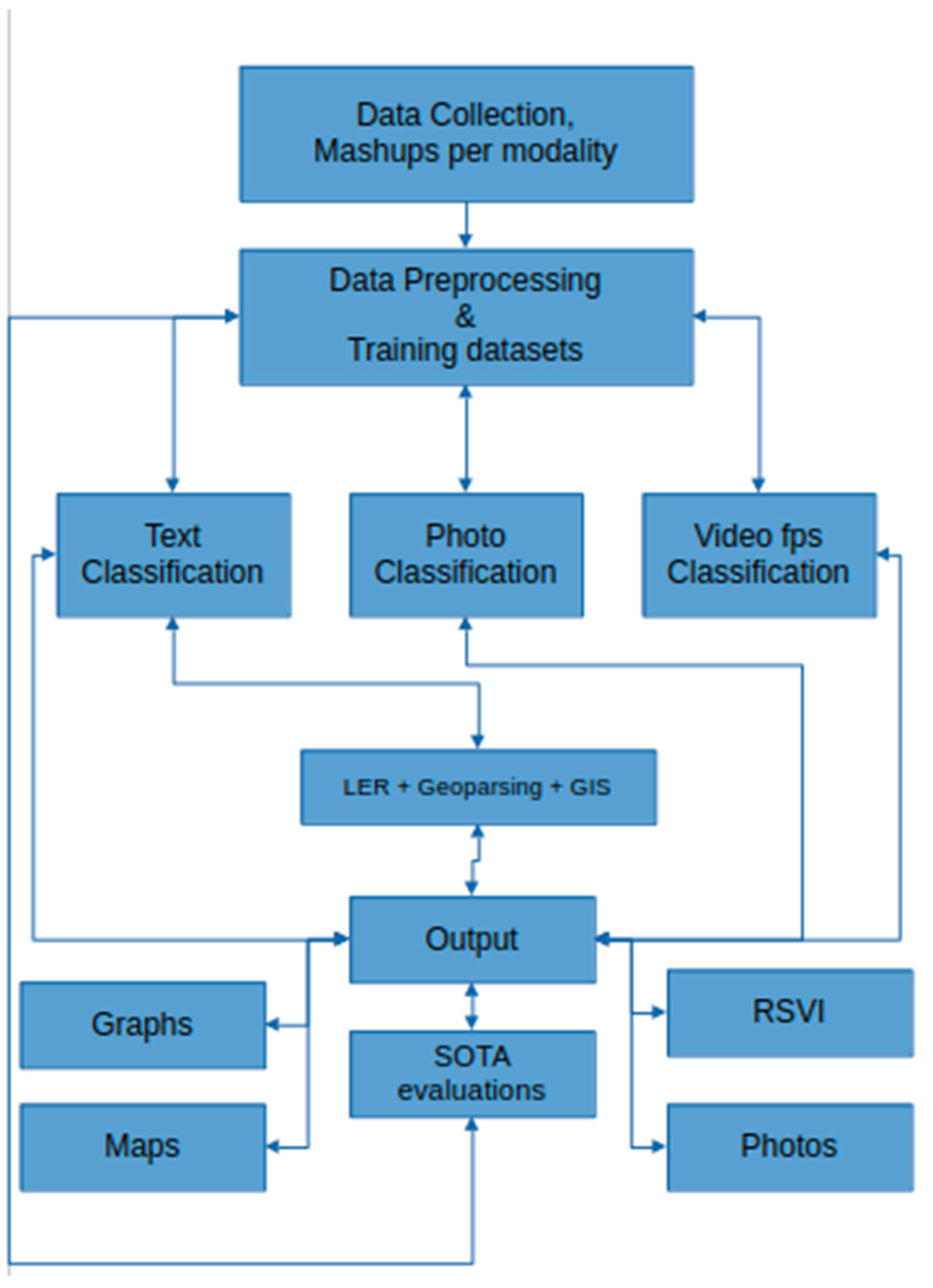

Methodology was organized into five main parts (

Figure 1). The first part was related to data collection, followed by the preprocessing of data from all modalities, which included among others the translation of the text strings that were not in Greek. Training text and photo/video models were the third and fourth parts, respectively. Part five was related to location entity recognition (LER) and all the related tasks for map creation. Finally, the presentation of the results completes the components of the current approach.

3.1. Data Collection

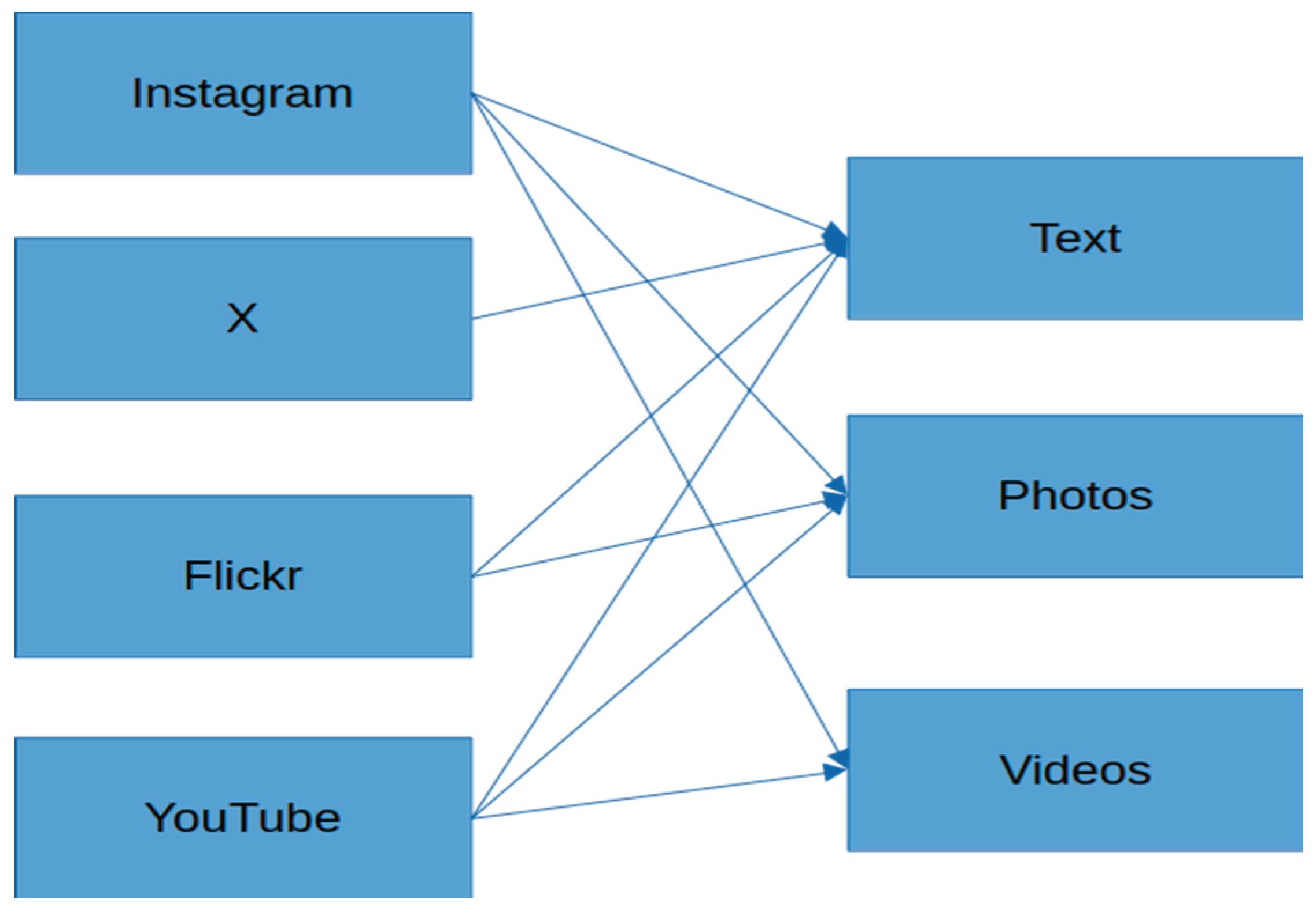

As already mentioned, various datasets of different modalities were used in the current research (

Figure 2). The Instagram dataset was scraped during 2020, after the occurrence of the Ianos medicane (Arapostathis 2020). The scraping of that time and the Instagram graph API up to the first weeks of 2025, in general, did not provide any specific parameters for defining the exact time period, apart from a ‘recent media’ endpoint. As a result, a lot of noise, consisting of posts shared previously, was accumulated.

The X (former Twitter) dataset was collected during July 2024 through the use of the Twibot app, while for Flickr and YouTube data two scrapers written in Python were created for that purpose.

The time period of interest for X, Flickr and YouTube was extended up to October 30, assuming that potentially some information regarding restoration and disaster management after the flood occurrence would appear, even though in many cases reference has been made to social media users tending to post during the flood occurrence and not afterwards (Soomro et al. 2024).

3.2. Preprocessing

Preprocessing was related to organizing the data from all sources together but for each one of the modalities separately. The text strings of Instagram, X, Flickr and YouTube (both title and description) along with the corresponding timestamps, and various IDs of the associated data (i.e., photo ids, video ids) were bound into a single data frame comprised of 7915 strings.

Processing included the translation of non-Greek texts, excluding the translation of hashtags, the removal of urls, the conversion to lowercase and the removal of various characters like dots and emojis. The translated and processed text strings were then ready for training the deep learning models.

Secondly the photos of Instagram and Flickr were bound into a single folder. Especially regarding Instagram, it should be stated that a caption was associated with more than one of the photos, while in some cases instead of photos there were videos. Some frames were extracted from the videos in order to enrich the photo dataset, while the video files were accumulated in a separate folder along with the YouTube videos.

Finally, with regard to the YouTube and Instagram videos, those were further processed for extracting frames at fps = 1 sec. The .jpg formatted frames were then stored at a separate folder, all of them with a filename suitable for associating the frames with the rest of the data in the event of that need (e.g., texts).

3.3. Classification

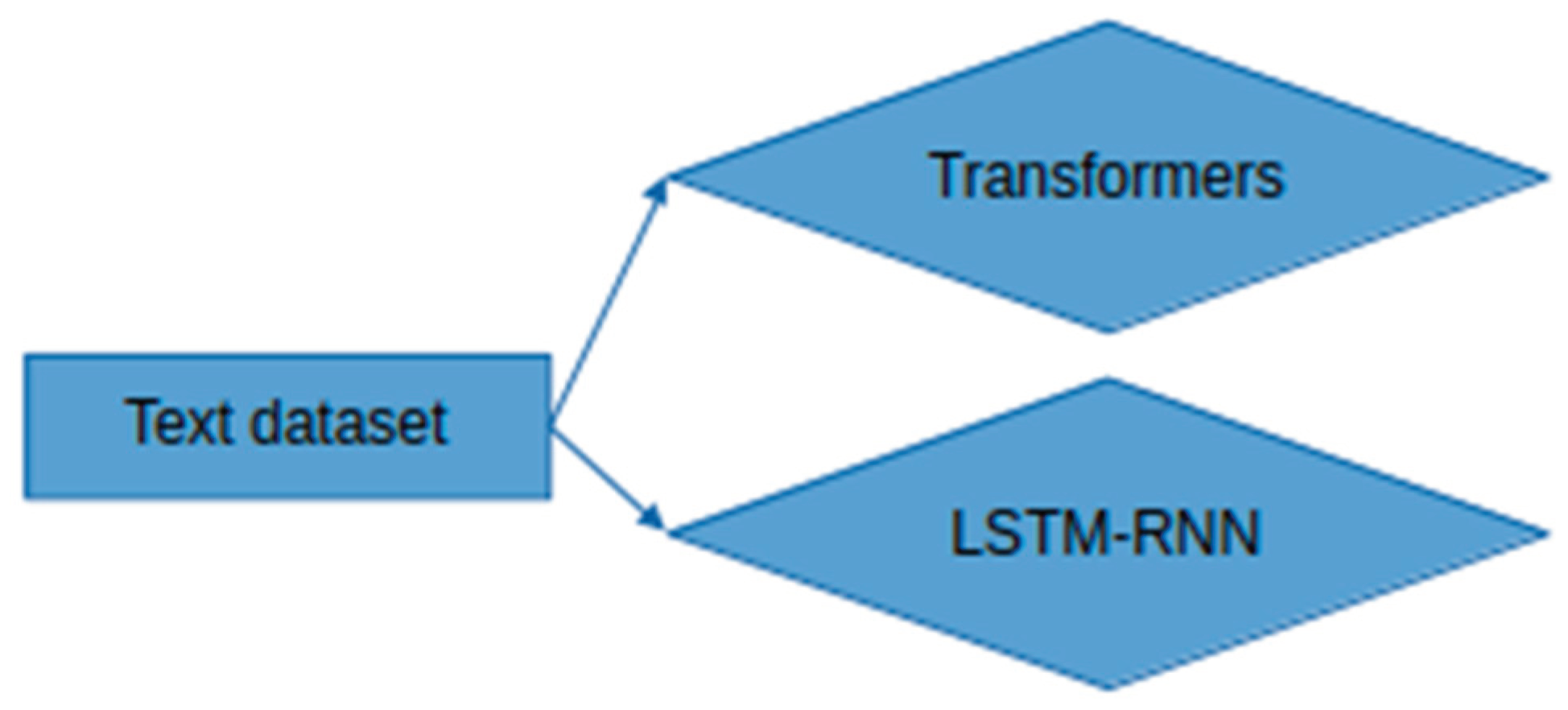

LSTM-RNN and transformers were employed for text classification (

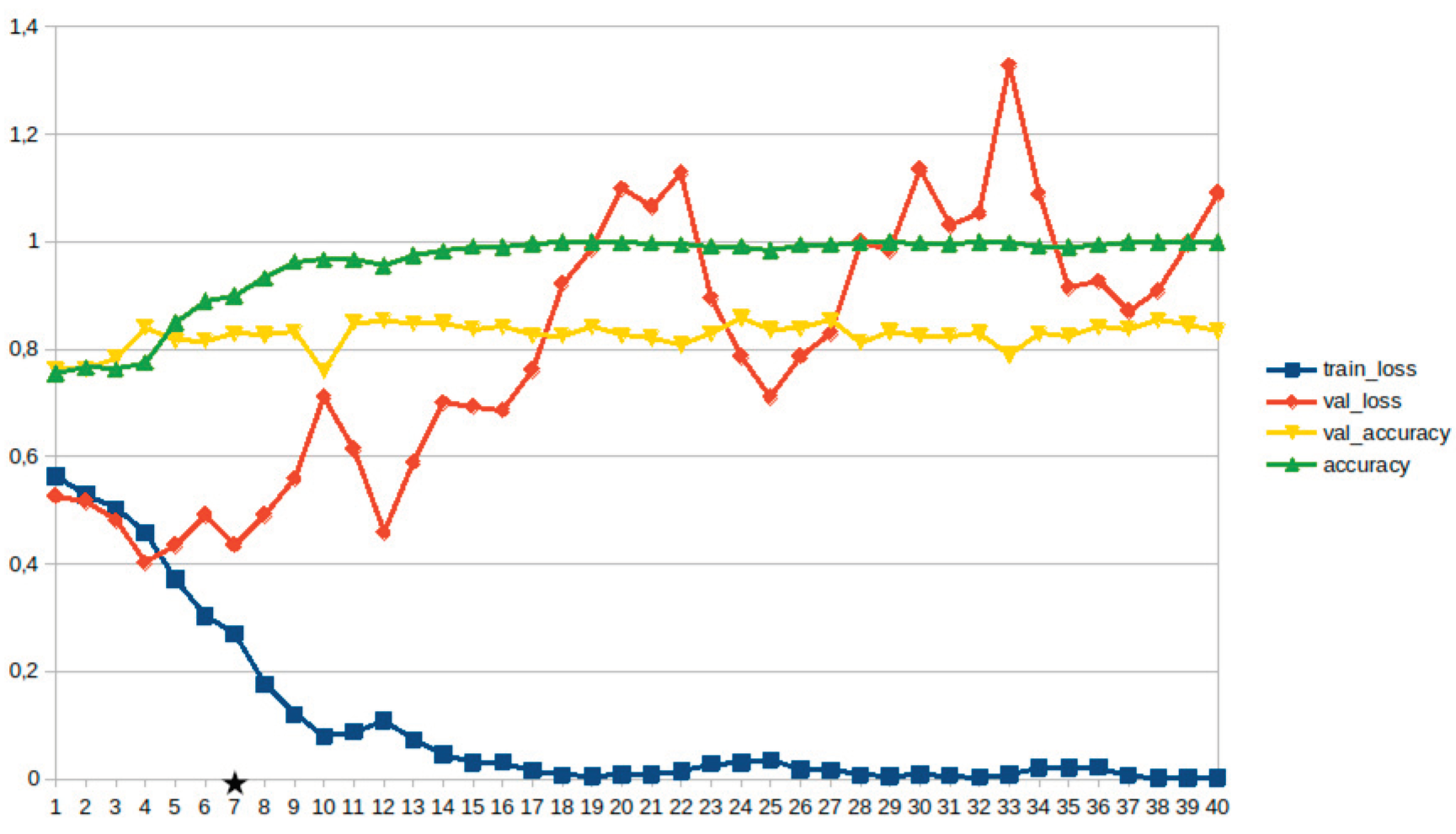

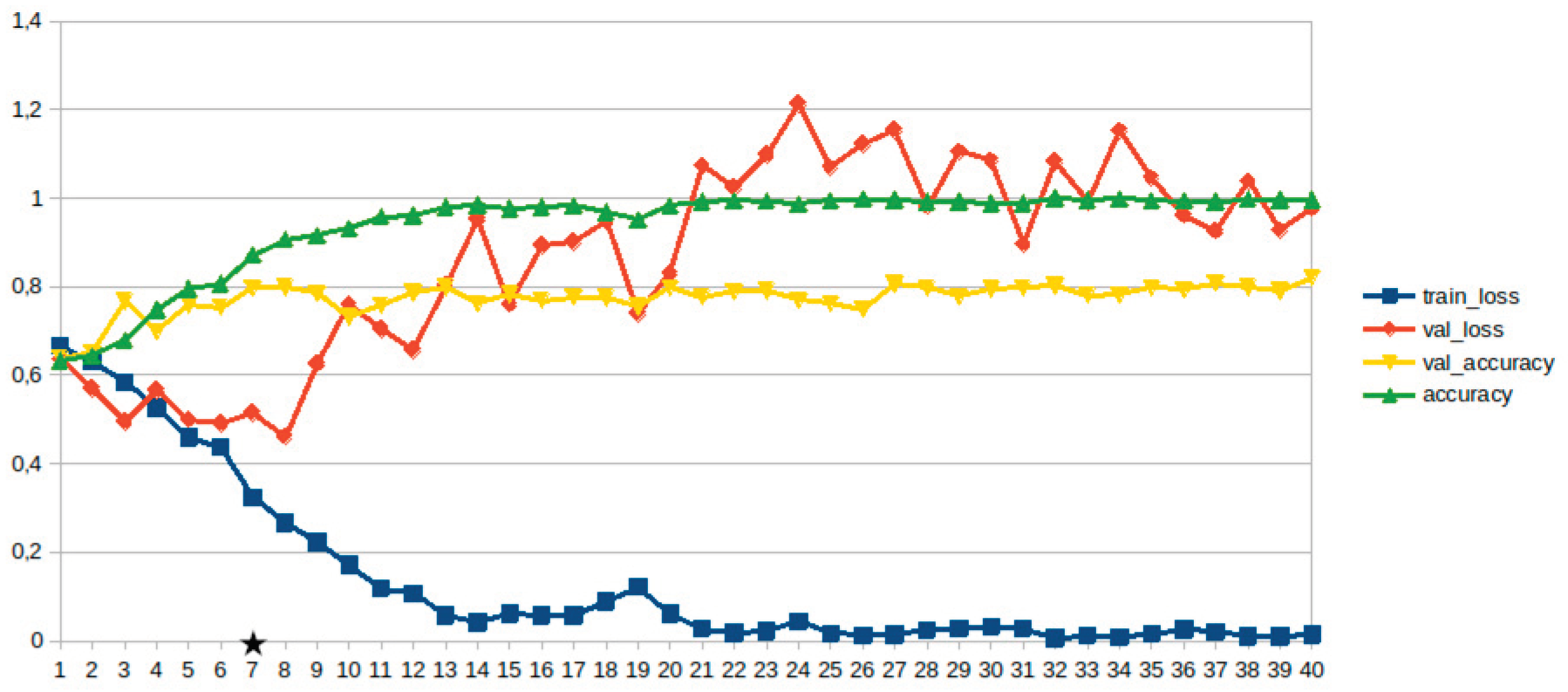

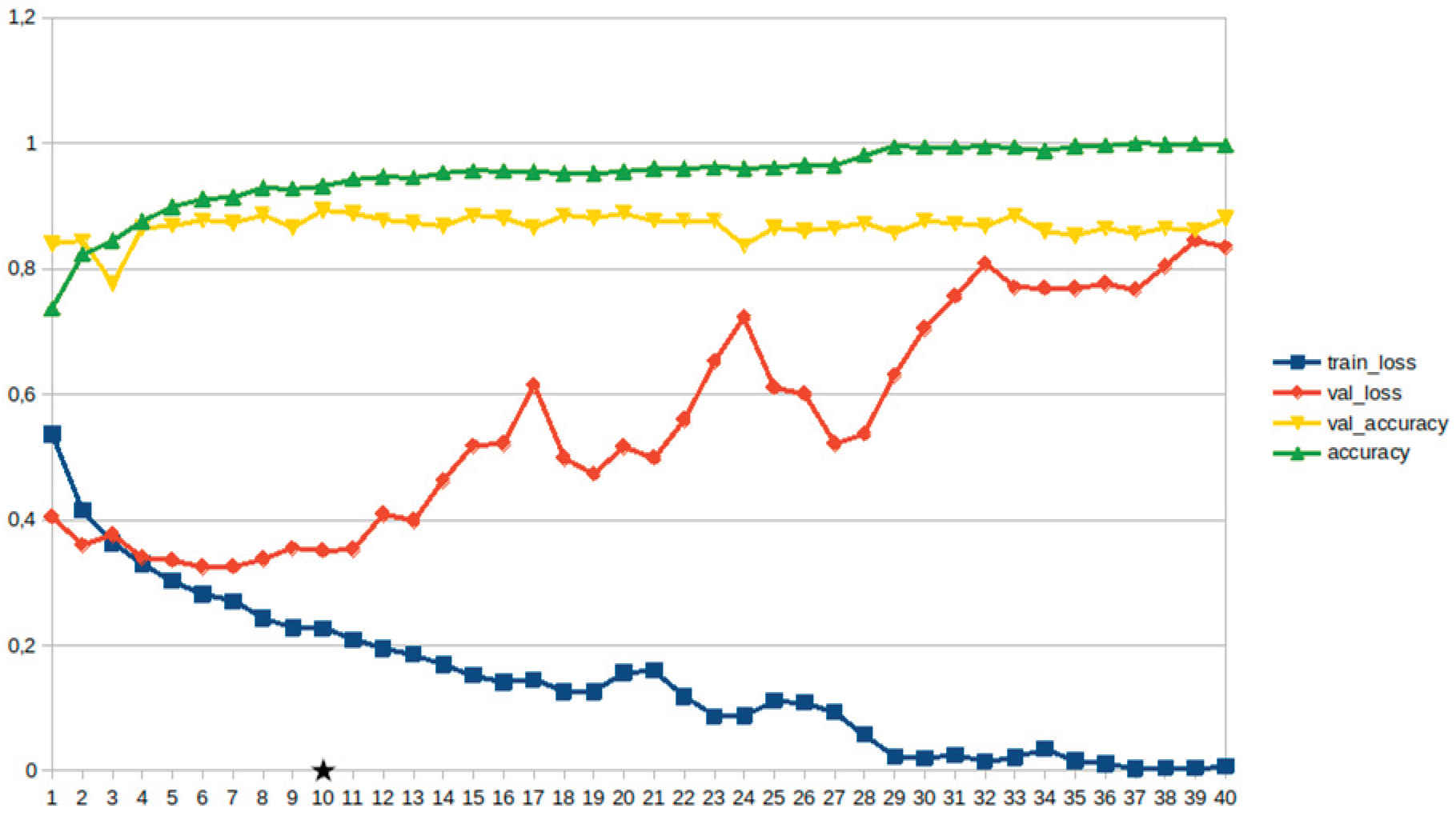

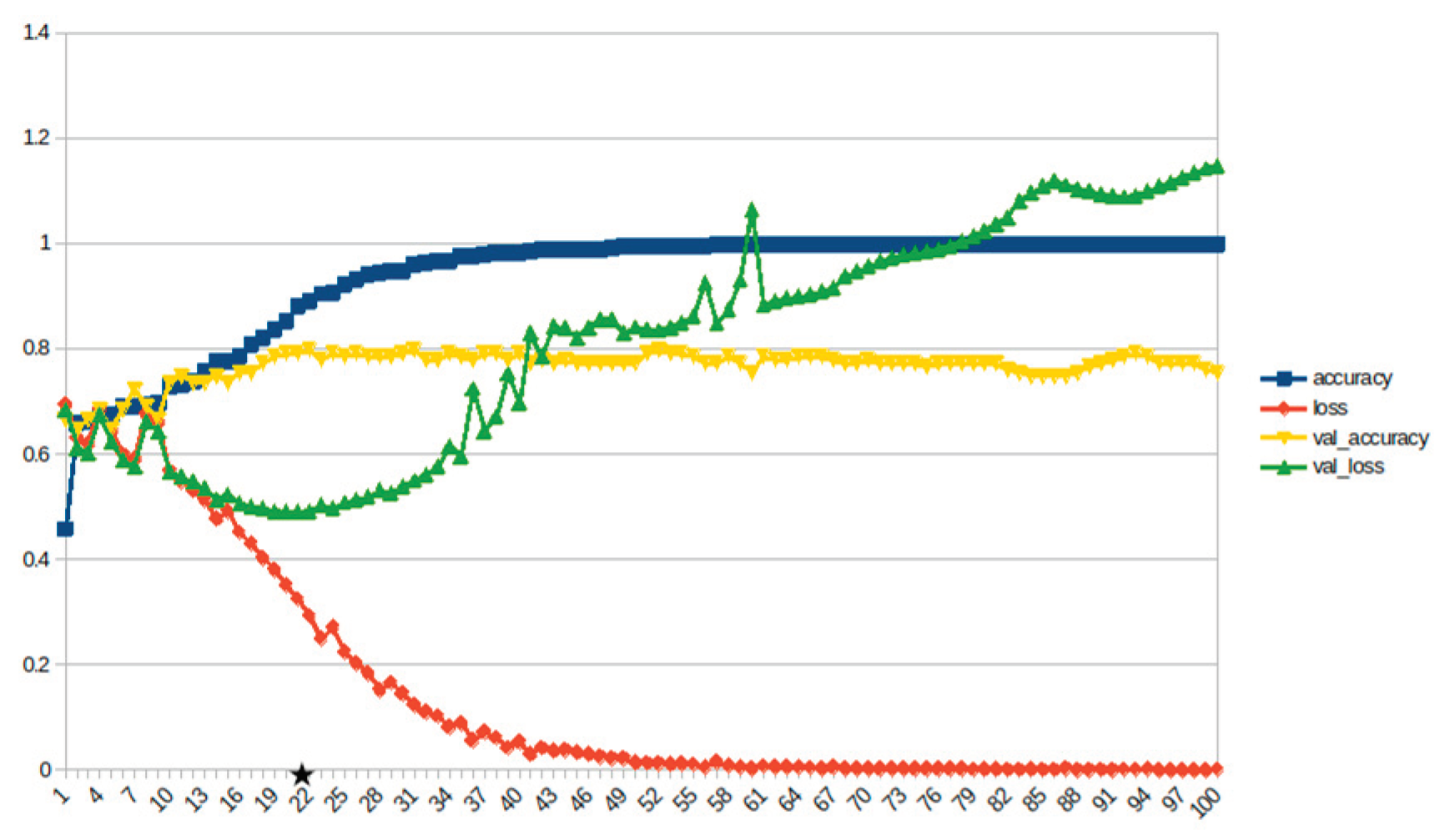

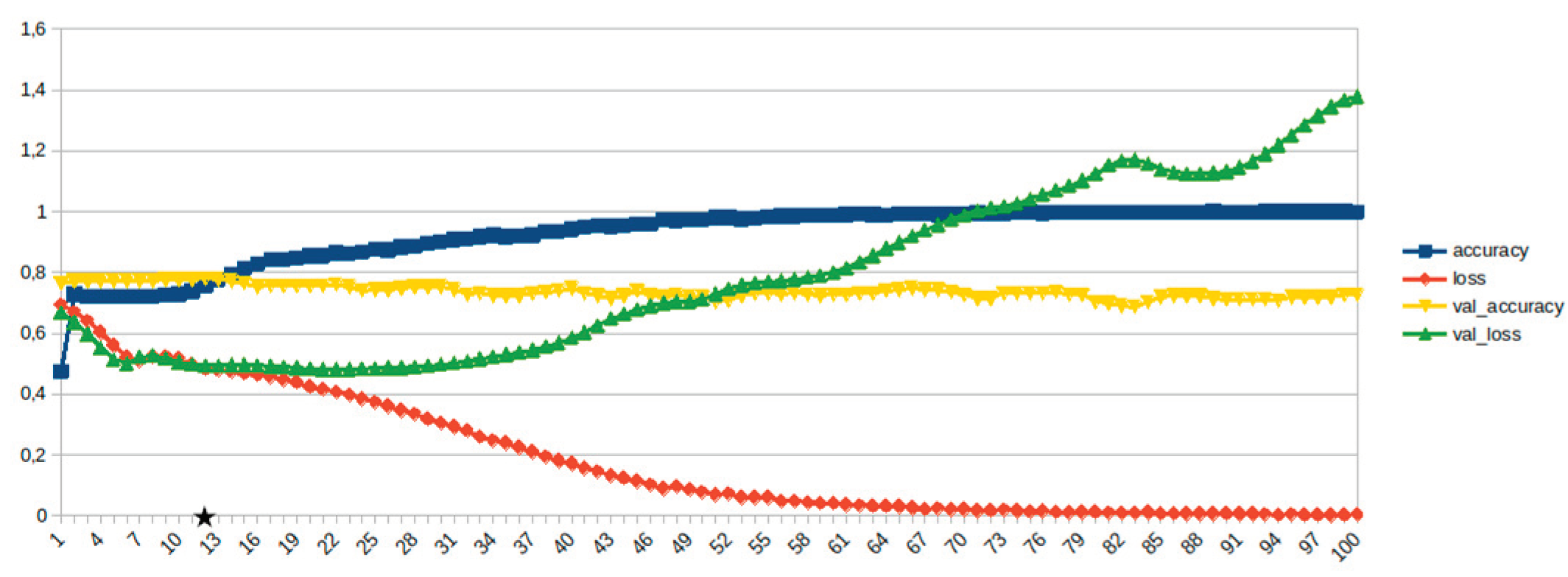

Figure 3). As previously mentioned, the author defined a classification schema consisting of five classes: I. Identification; II. Consequences; III; Tracking and Disaster Management; IV. Weather/Meteo Info.; and V. Emotions, Opinions and Other Comments. There was a long-term experimentation to define the parameters for both models. The final parameters are presented in the results section, where the author emphasized on the importance of the dataset, respecting performance, among others. For that purpose, to select the appropriate classifier the author compared the SOTA metrics of both the LSTM-RNN and transformers by using two different training datasets. The first consisted of approximately 10% of the data, and the second of approximately 15%. One aspect that is worth mentioning is that the author used custom epoch values, based on the balance between Training Accuracy and Validation Accuracy, thus avoiding over-fitting. In other words, even if Training Accuracy was up to 100%, the appropriate balance ensures more ‘compatible’ training. Therefore, the selected epoch in all of the related graphs in the results section is indicated with a star.

Table 1.

Classification Schema Followed for Text Classification.

Table 1.

Classification Schema Followed for Text Classification.

| Class Name |

Brief Description |

| Identification |

Only simple identification regarding the presence of rain, strong wind etc. Not past events |

| Consequences |

Consequences of the Ianos: Damage, difficulties in everyday tasks, human loss, injuries, floods, electricity cut, etc. |

| Disaster Management |

Everything regarding Tracking and Disaster Management: Information about the status, consequences, red alerts, posts that imply in situ information in photos. |

| Weather |

All information related to: meteo; meteo announcements; actual reports regarding weather: rain, rainy day, sunny day. Past events are not included apart from reports like: ‘rain just stopped’. |

| Emotions, Opinions, Comments, etc. |

Emotions, opinions, comments related to Ianos only and connected effects. Statements of politicians, blame, criticism of the authorities, links like ‘read more’ and characterizations of the situation are also included. |

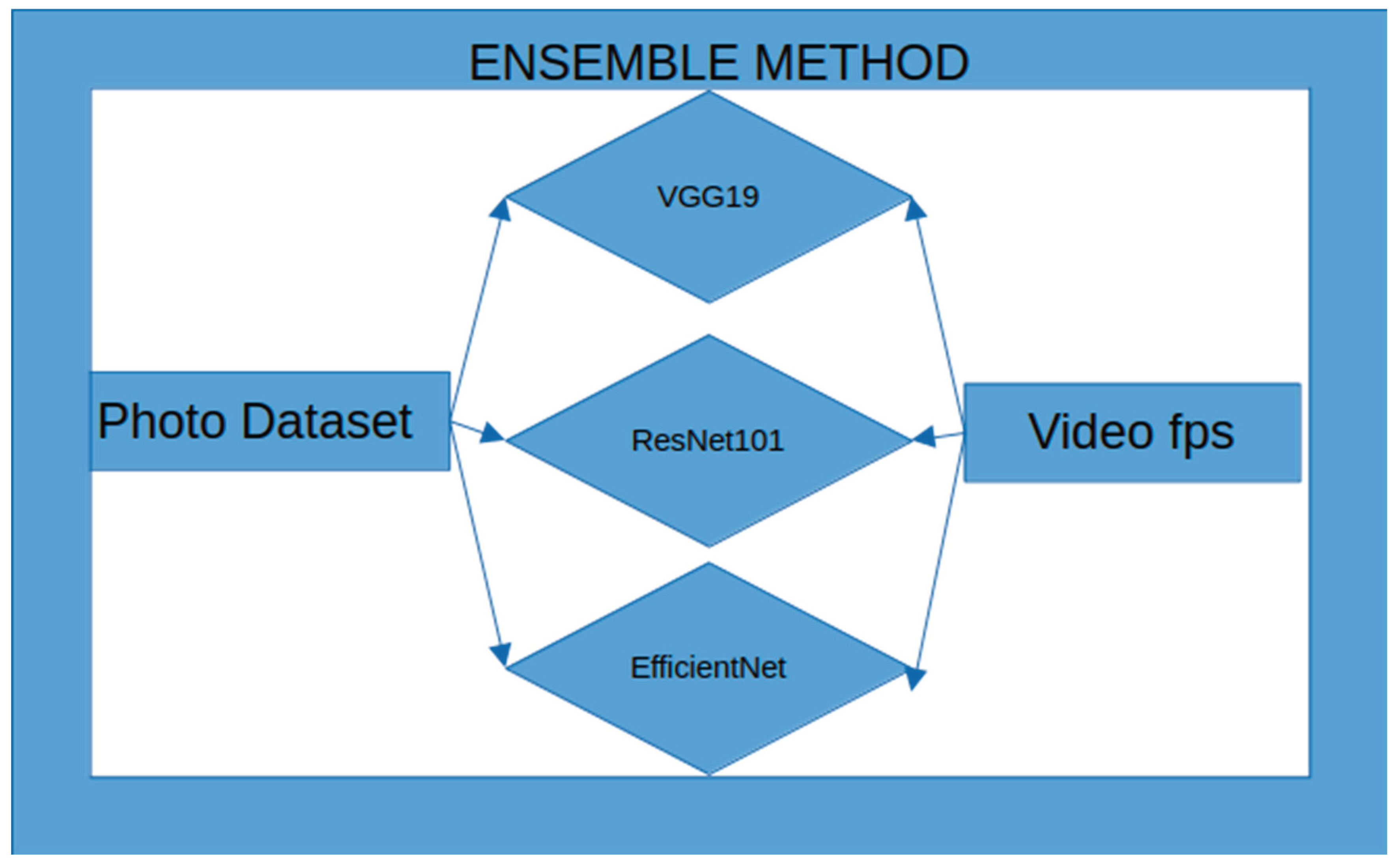

For photo classification, the author fine-tuned a VGG-19 model for classifying the related photos in two main classes: 1. Related and 2. Not related to Ianos. As previously mentioned, the dataset used was the Deucalion, enriched with various photos of current sources. The enriched version of Deucalion was also used for fine-tuning a ResNet101, along with an EfficientNet model in the same binary classification. As per text classification, the author selected the appropriate models by considering the balance between Training accuracy and Validation accuracy. In other words, if the difference of the two metrics was more than a specific threshold then the model was not saved and was not used. Therefore, as per text classification models, the epoch in which the model was saved is indicated with a star.

Videos were processed as a set of photos extracted at an analogy of 1 fps. Based on that set of photos, the author defined and calculated the Relevant Share Video Index (RSVI). RSVI was estimated by estimating the proportion of relevant frames to the total ones, at step k, which is the value of extracted frames per second. In our case, as already mentioned, this was set to 1 s.

Upon extracting the frames from all videos and classifying them through the ensemble method, the author finally proceeded to the RSVI estimation. The actual interpretation of current index is that the bigger the value of the RSVI and more related frames existed in the set of extracted frames.

Ensemble Approach: The 3 Guessers: Probabilities Scenario

In that section the author presents the essential theory on which the ensemble method is based on. Let’s assume that there are three guessers. Guesser A guesses with an accuracy P1 while Guesser B guesses with an accuracy of P2. Finally, guesser C guesses with an accuracy of P3. The probability of having only one guesser having a correct guess is defined as:

pi: The probability that the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, respectively predicted correctly.

1-pi is the probability that the ith predicted wrongly.

The probability of having one guesser correct and the two other wrong is estimated as:

while the percentage of having correct output by considering at least the two-thirds is estimated as:

pi = the probability of ith voter to be correct

q1 = 1—pi, the probability of the ith voter to be wrong

This approach actually describes the estimation of the accuracy of the ensemble method based on a voting system, in which each voter has a value of one as long as the voter’s Acc > 0.5. Since all the guessers in our case received accuracy of more than 50%, the vote of the two, either estimating the sum of weights or each one as one, is the majority. So, in the current case, the approach considers as always correct the decision of at least the two-thirds of the guessers. In our case it could be said that the classifiers are assigned the role of those briefly described “guessers”. In (3) it is assumed that errors are uncorrelated between models. In practical cases, actual ensemble performance may vary depending on error correlation, which is not directly measured in this current research.

3.4. Location Entity Recognition (LER) and GIS Processing

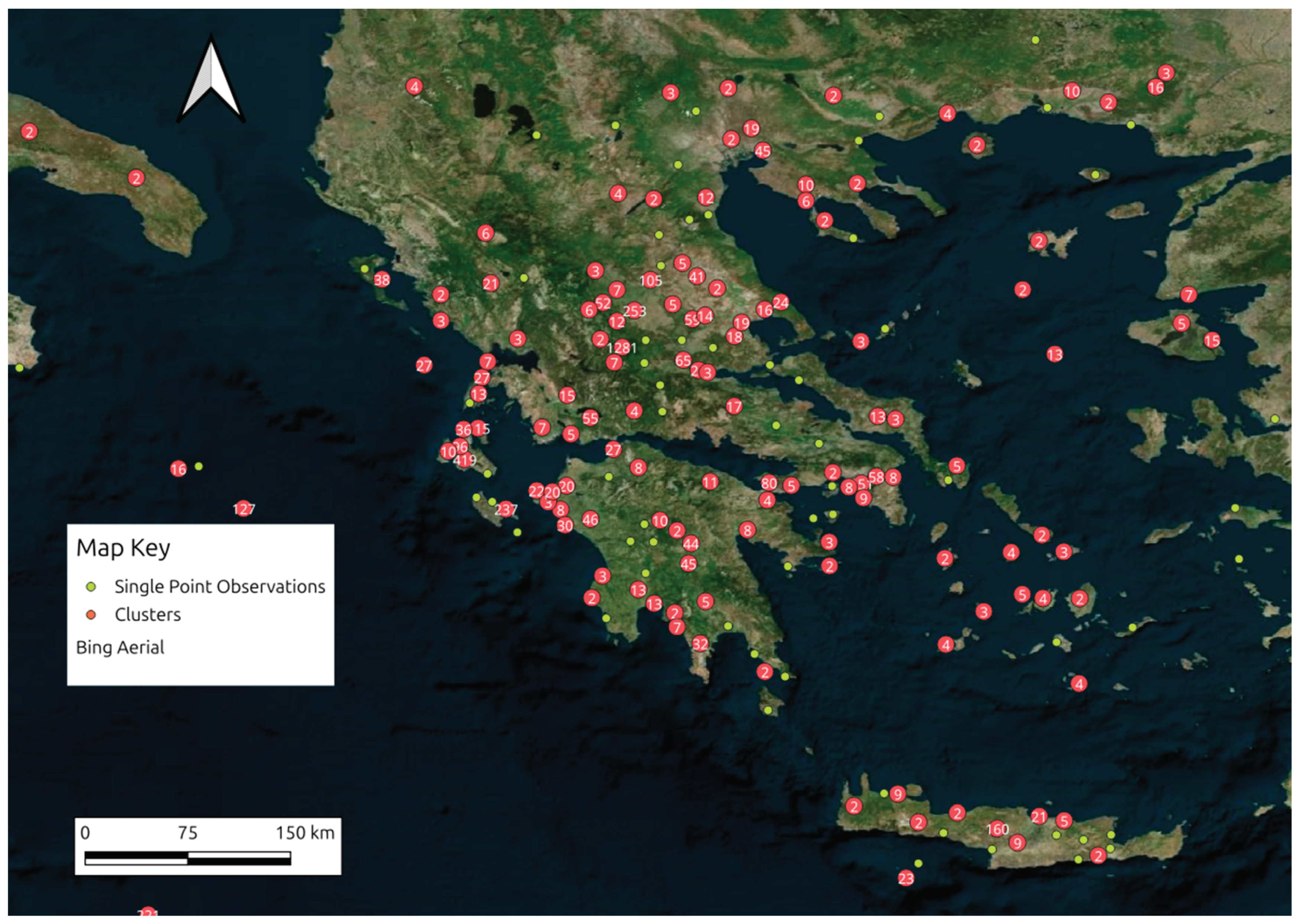

The author used a transformer pretrained in Greek, available through the GR-NLP-Toolkit (Loukas et al. 2024) for detecting location in the text corpus of the mash-up. An ensemble method was applied using conventional geoparsing as well as for increasing the accuracy of the model. The detected geolocations were geocoded by using commercial geocoding APIs while they were processed in a GIS environment, including filtering of the geocoded locations within the geographic area of interest (GAOI).

Figure 4.

Models and data participating in current ensemble approach for photo and video processing.

Figure 4.

Models and data participating in current ensemble approach for photo and video processing.

Figure 1.

Main components of the methodology.

Figure 1.

Main components of the methodology.

Figure 2.

Data sources and data types used.

Figure 2.

Data sources and data types used.

Figure 3.

Deep learning models for text classification.

Figure 3.

Deep learning models for text classification.

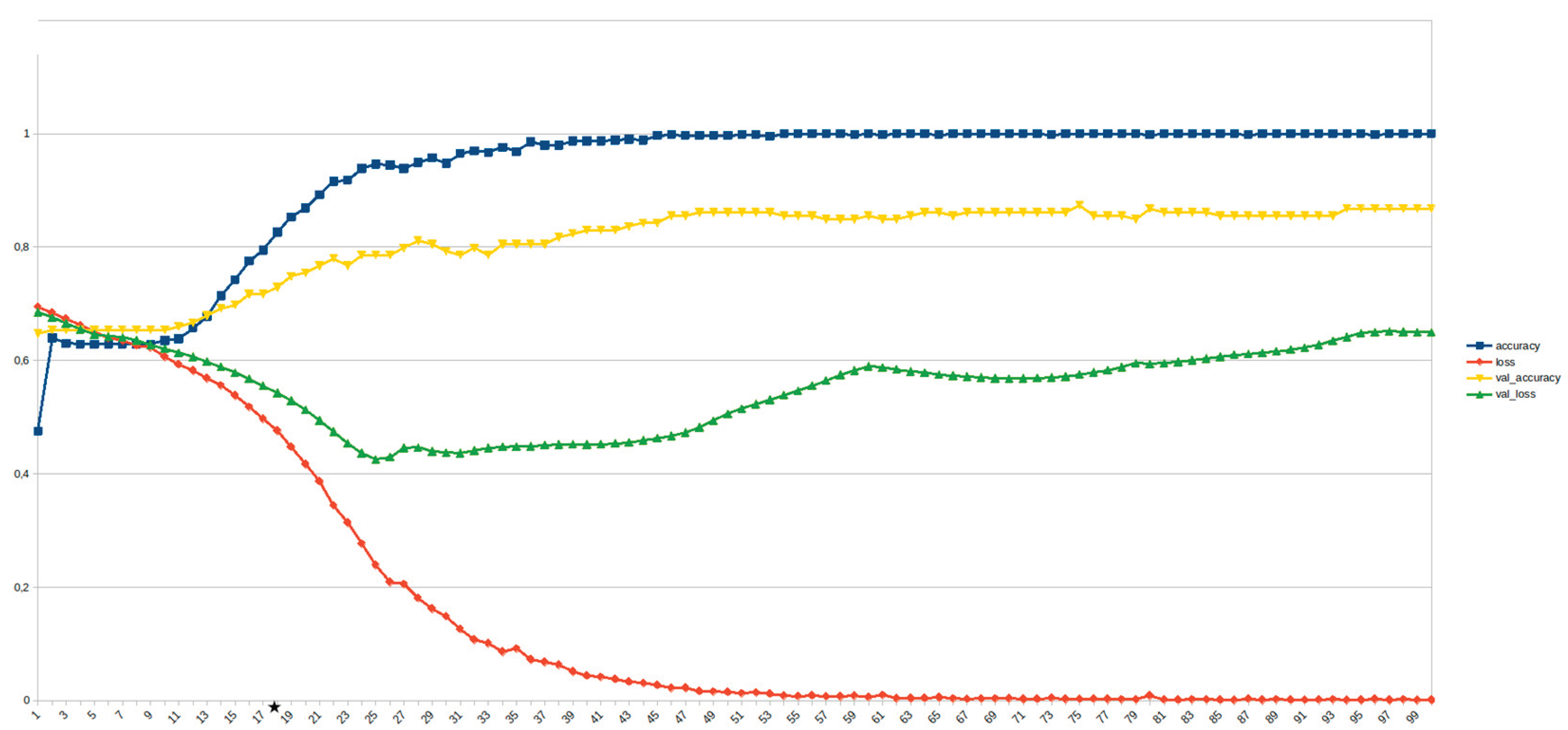

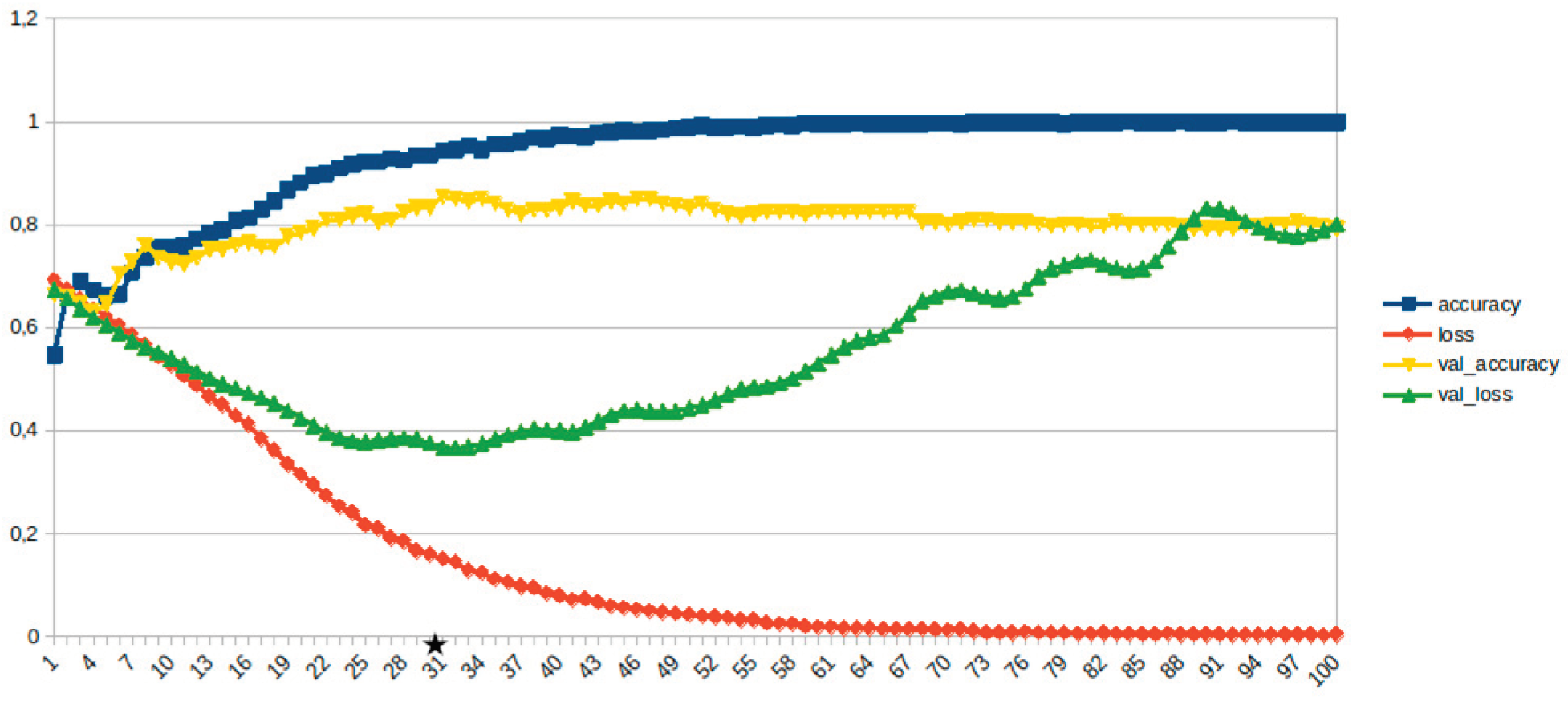

Figure 5.

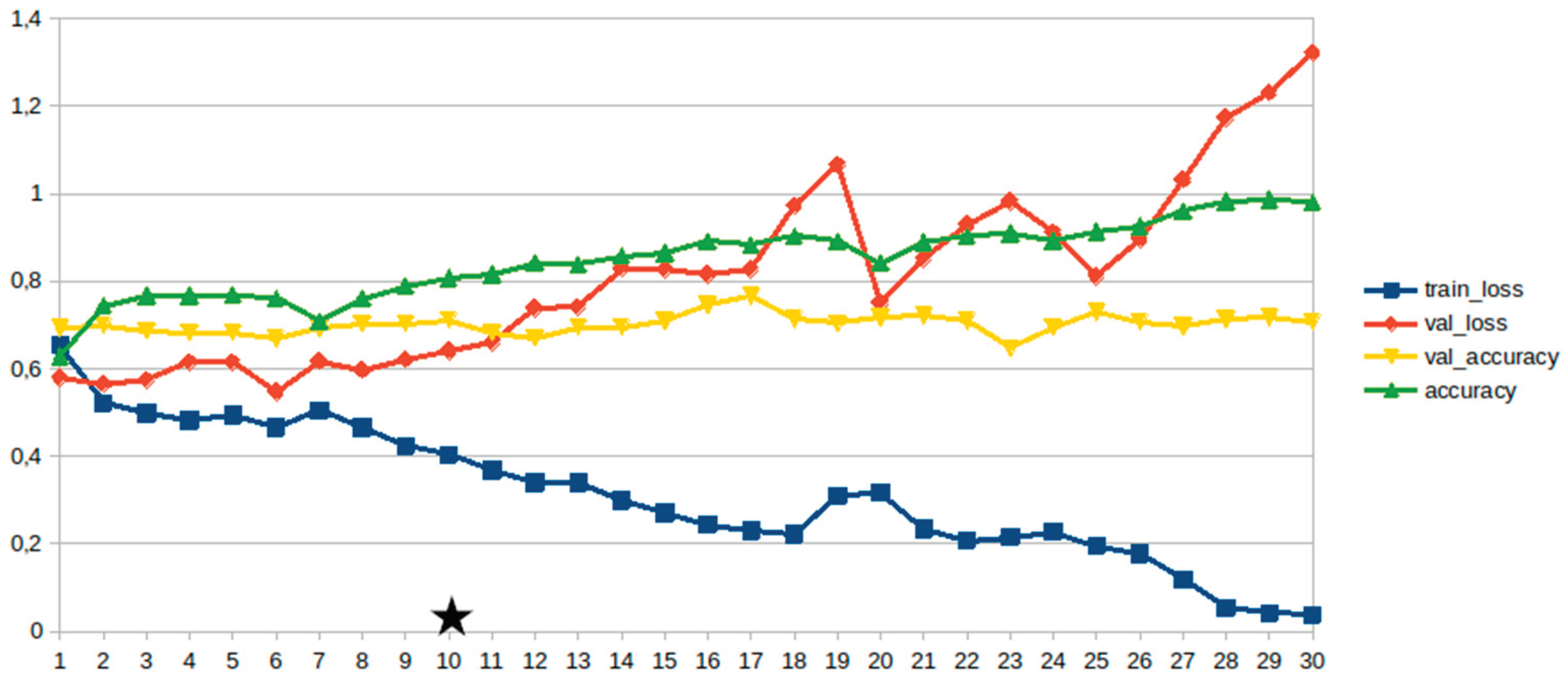

Transformers, emotions, opinions etc. ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 5.

Transformers, emotions, opinions etc. ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

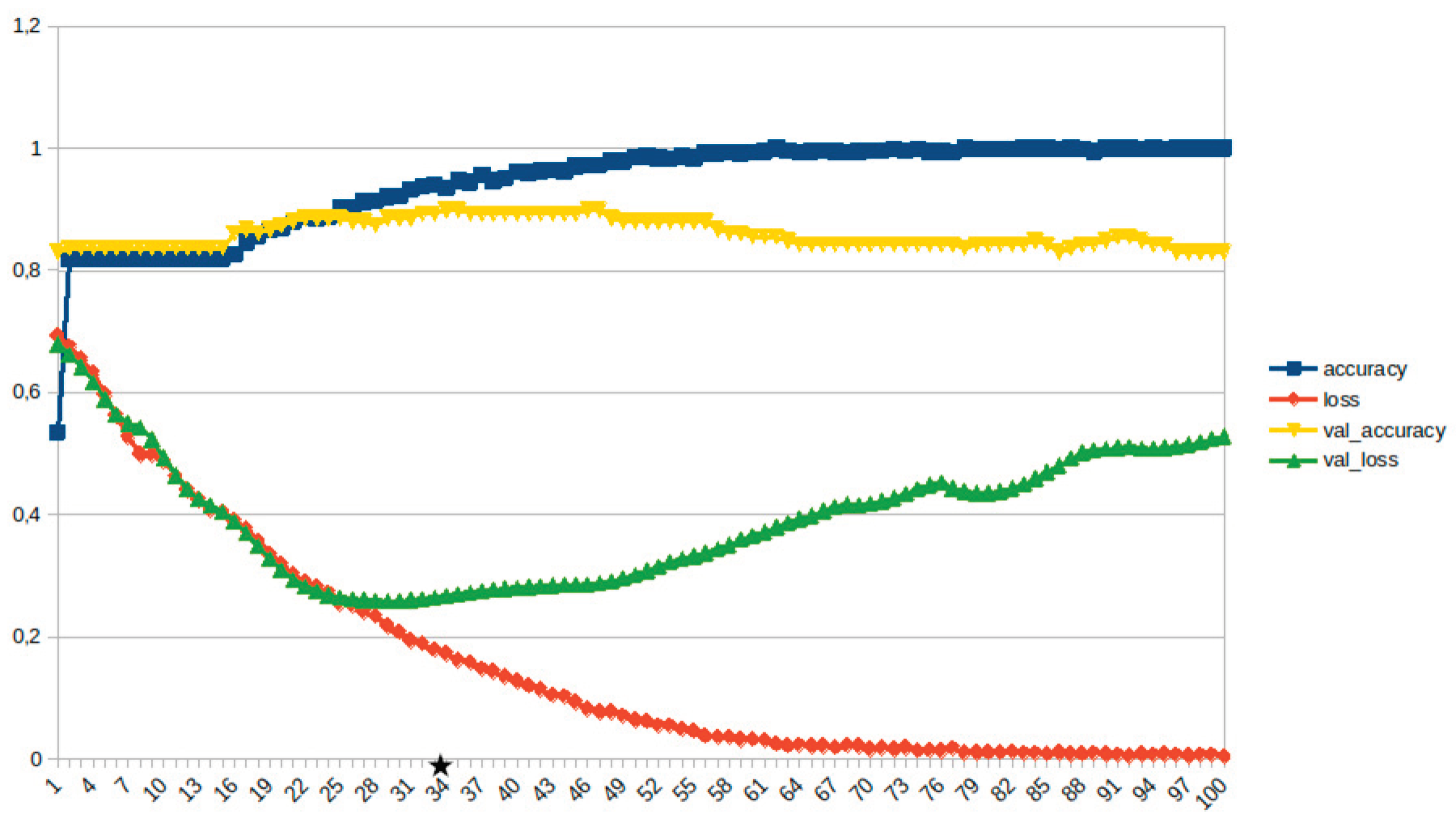

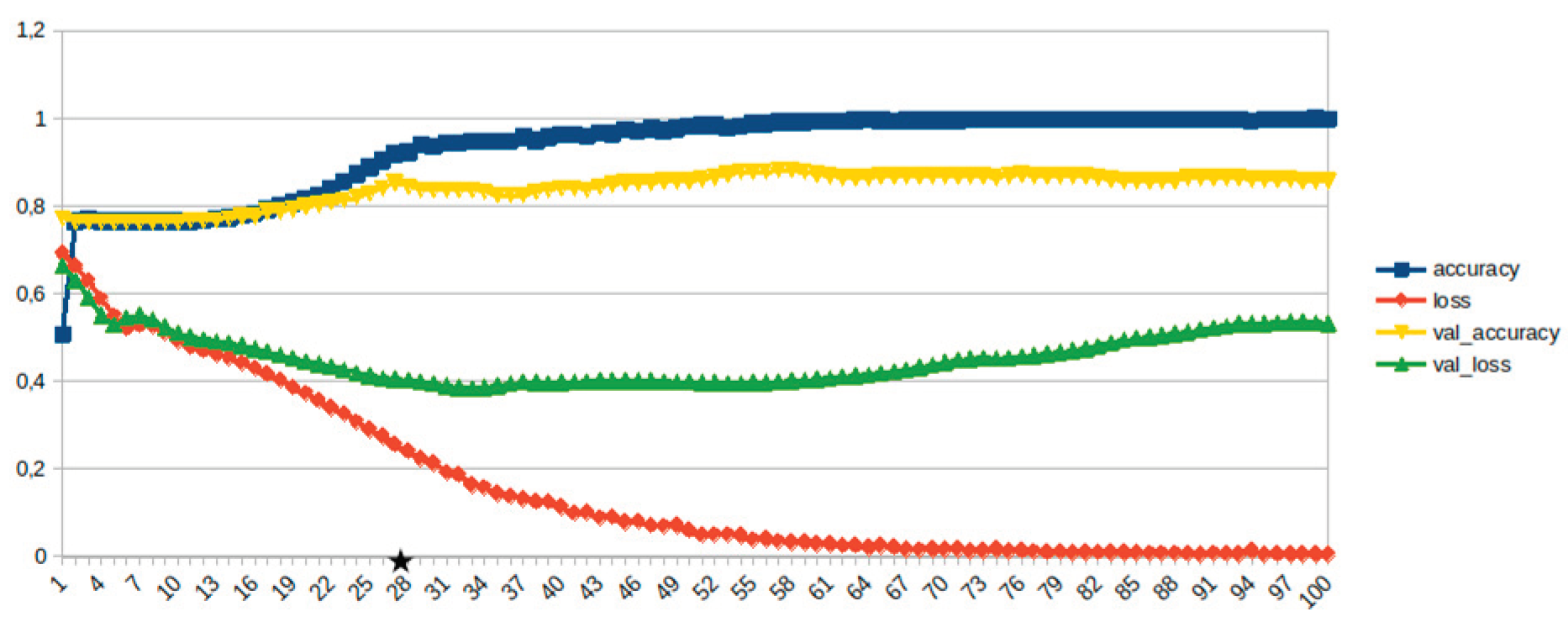

Figure 6.

Transformers, consequences ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 6.

Transformers, consequences ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

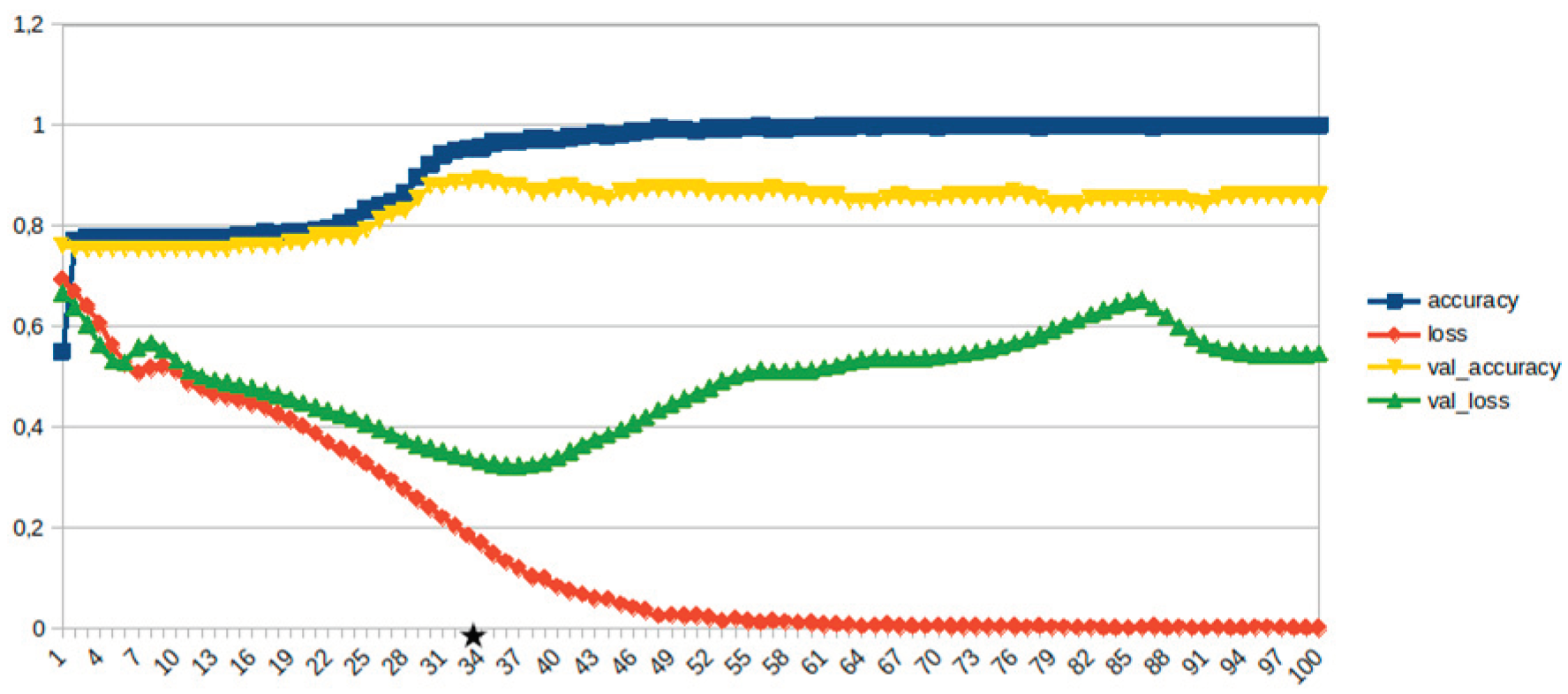

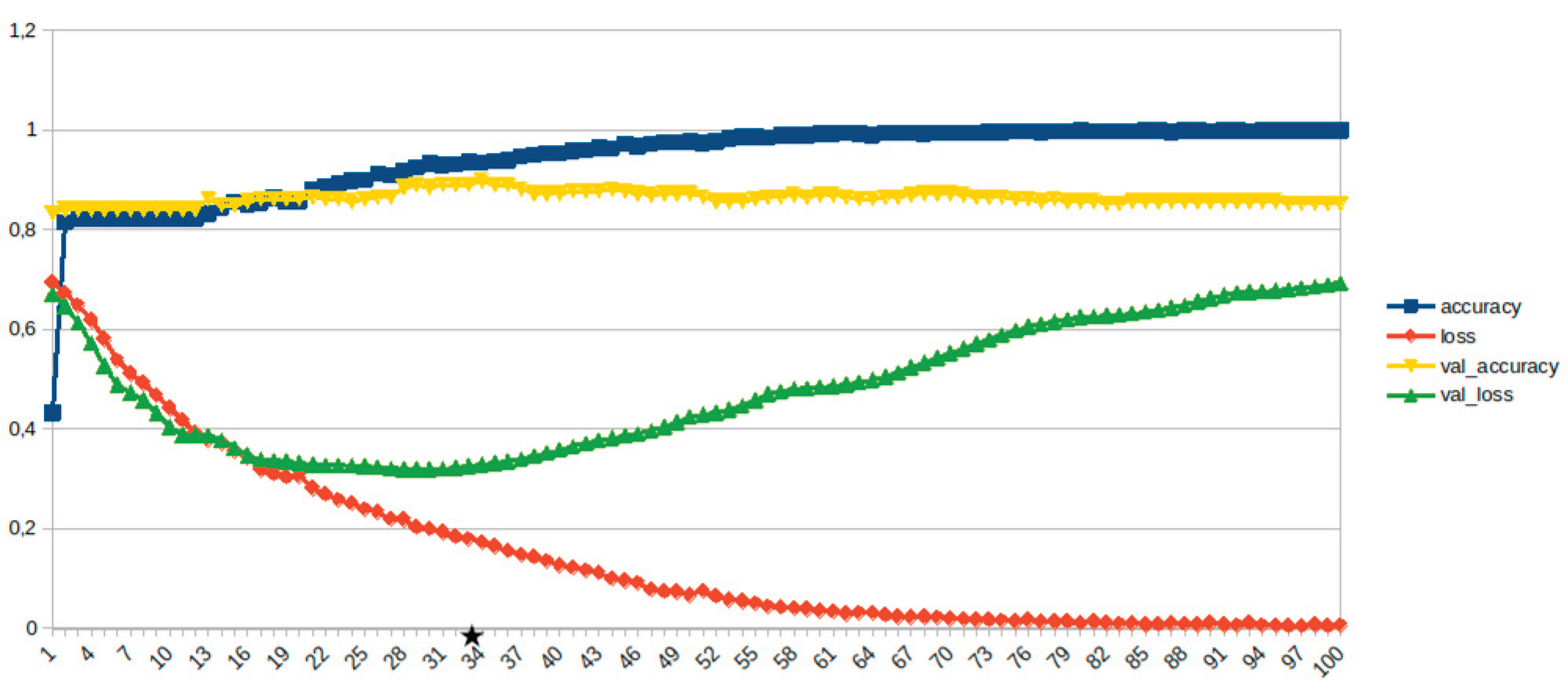

Figure 7.

Transformers, disaster management ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.).

Figure 7.

Transformers, disaster management ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.).

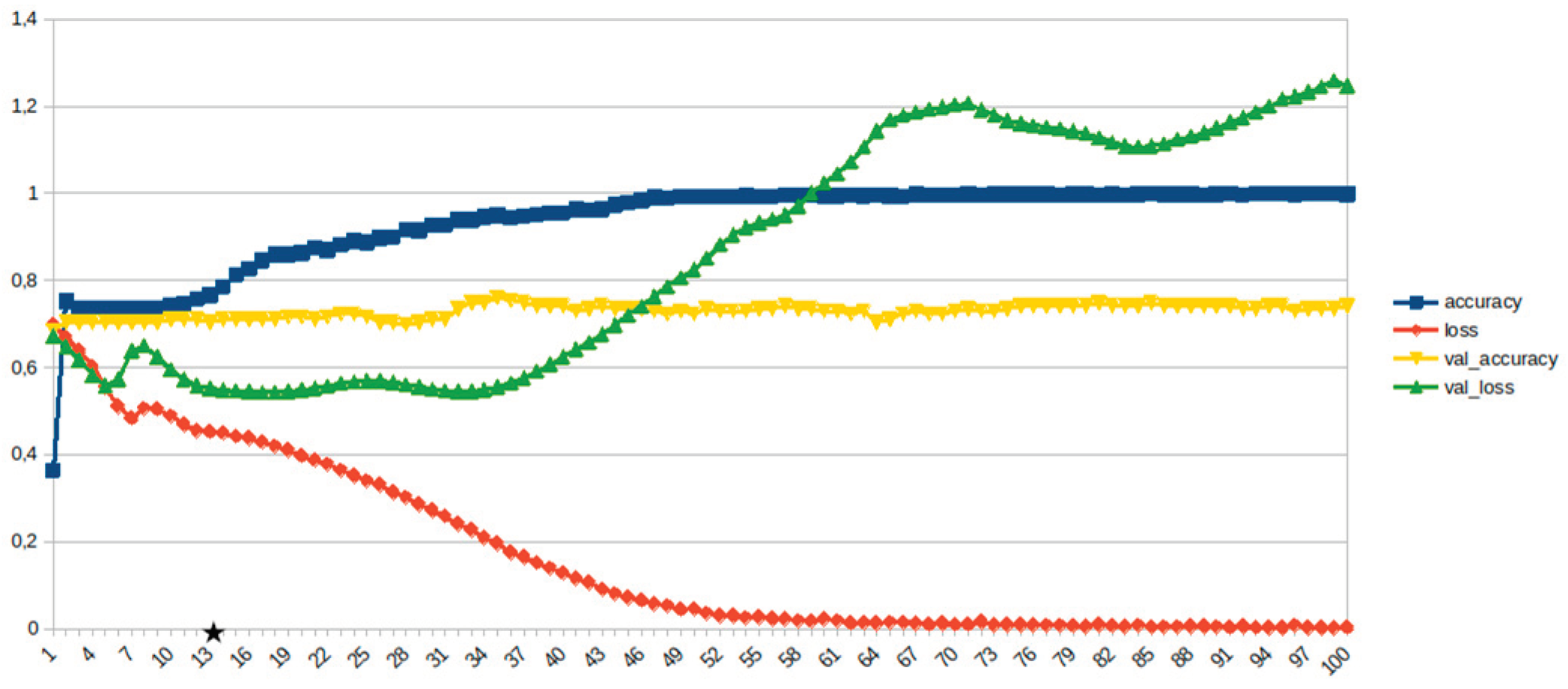

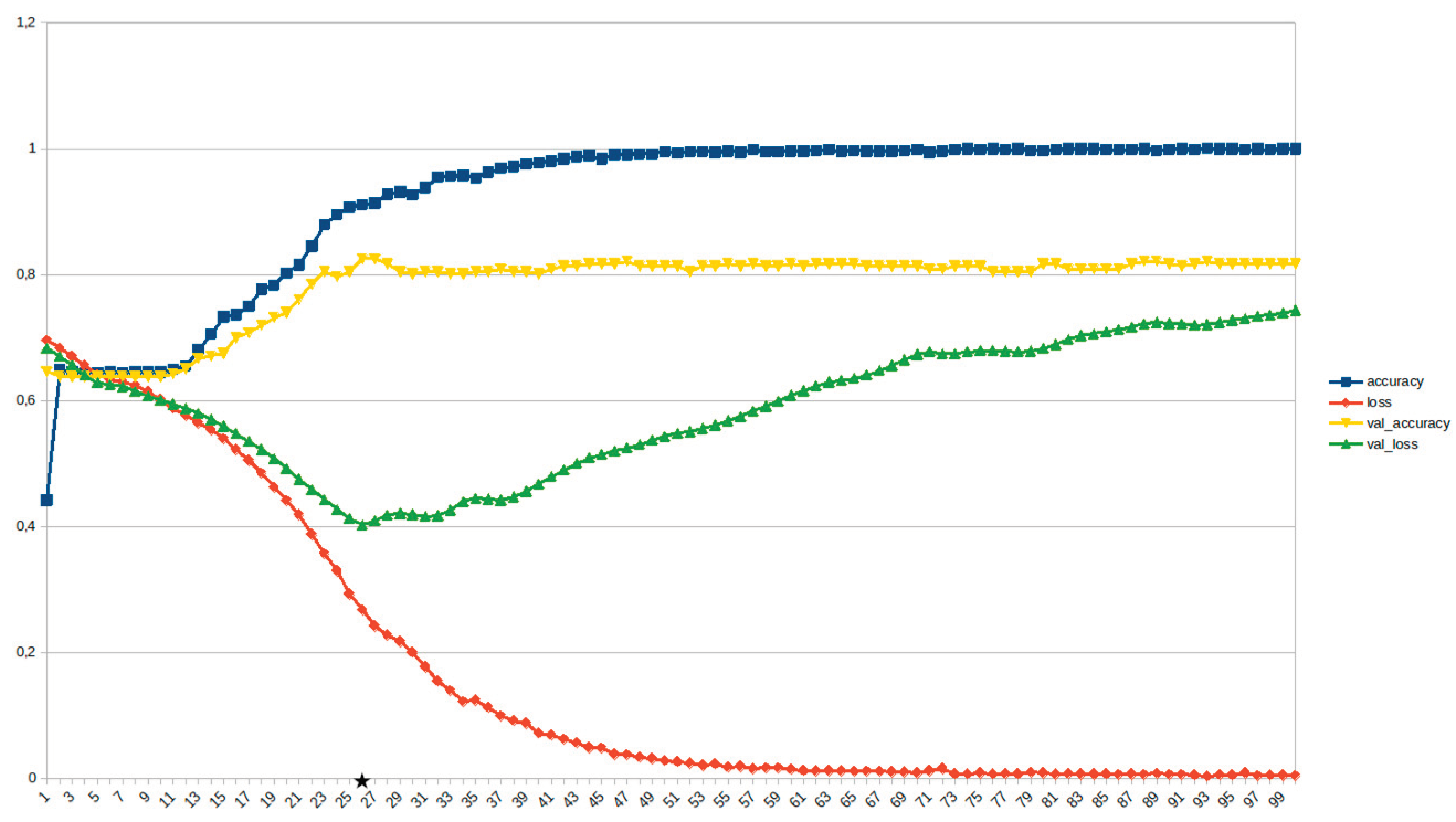

Figure 8.

Transformers, weather ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.).

Figure 8.

Transformers, weather ~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.).

Figure 9.

Transformers, identification~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 9.

Transformers, identification~10%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 10.

Transformers, emotions, opinions etc. ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 10.

Transformers, emotions, opinions etc. ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

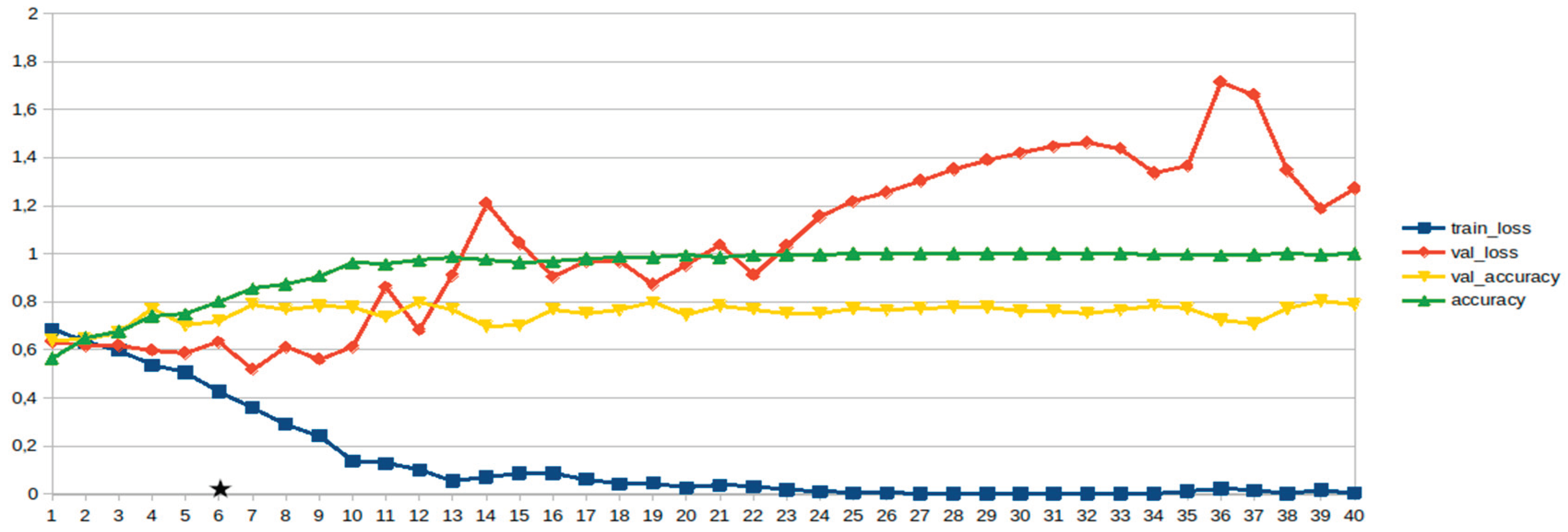

Figure 11.

Transformers, consequences ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 11.

Transformers, consequences ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

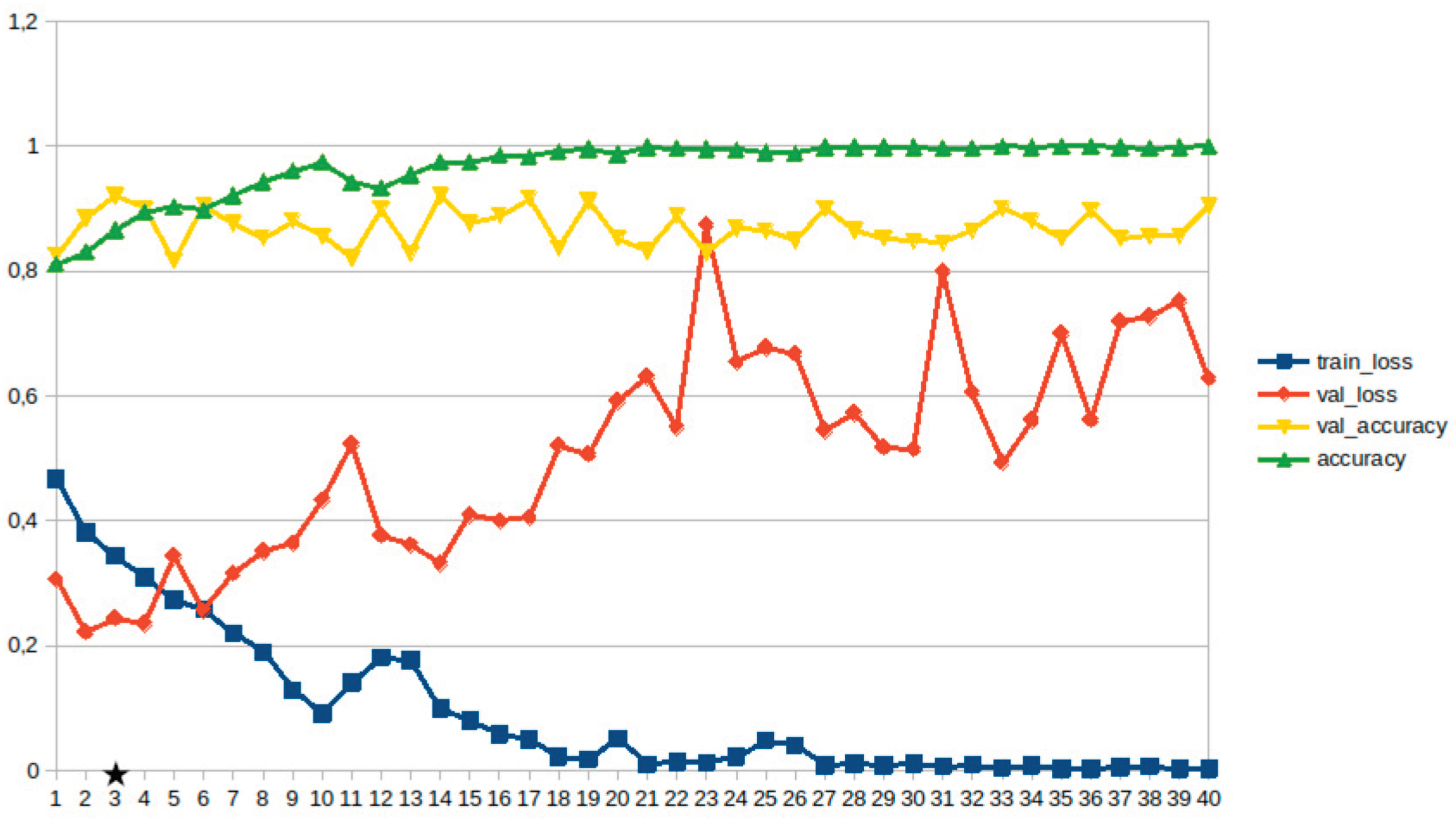

Figure 12.

Transformers, weather ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 12.

Transformers, weather ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 13.

Transformers, identification~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 13.

Transformers, identification~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

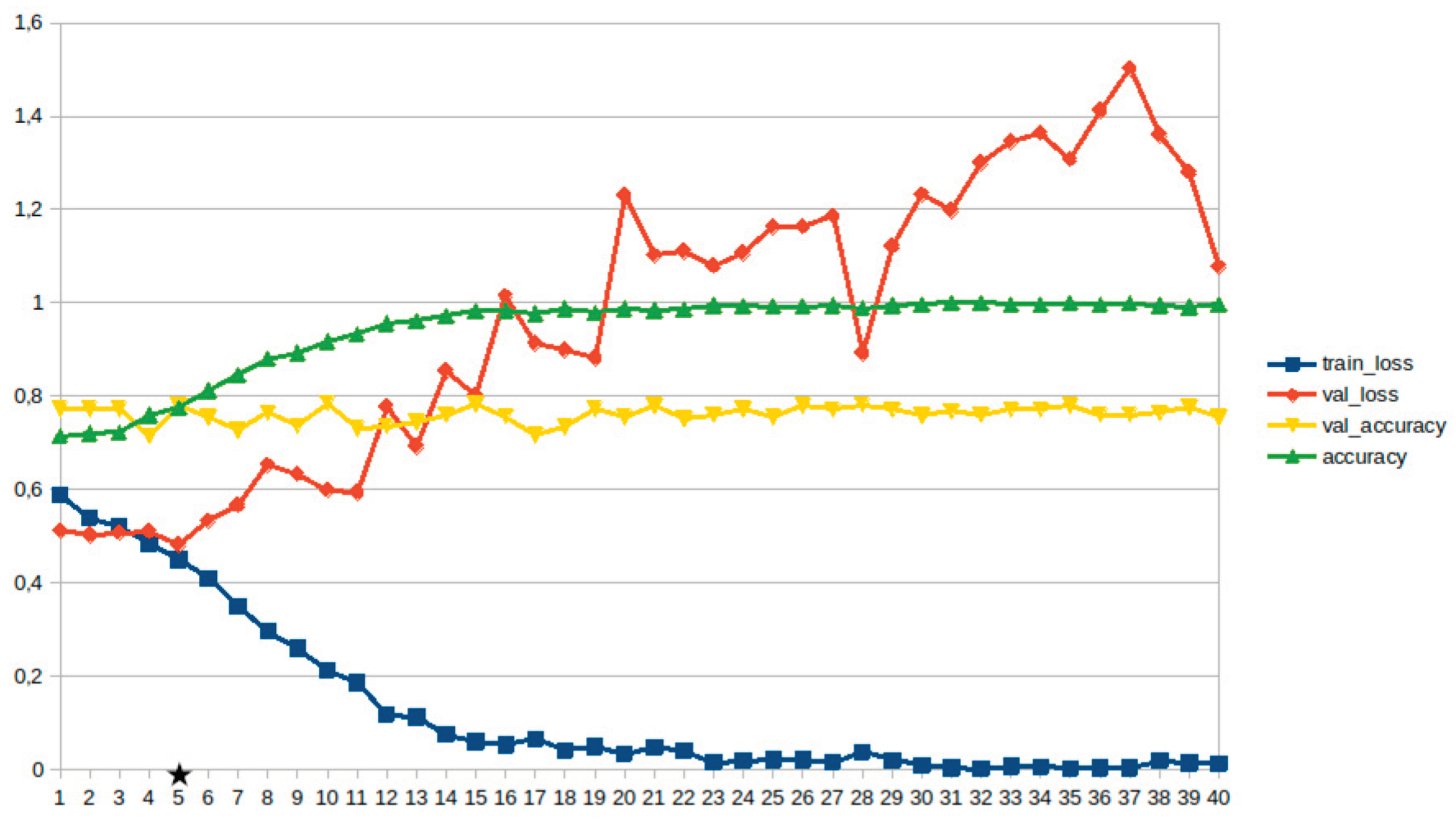

Figure 14.

Transformers, disaster management ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 14.

Transformers, disaster management ~15%. (Star indicates the best balanced model.)

Figure 15.

LSTM, Disaster management ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 15.

LSTM, Disaster management ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 16.

LSTM, weather ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 16.

LSTM, weather ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 17.

LSTM, identification ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 17.

LSTM, identification ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 18.

LSTM, consequences ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 18.

LSTM, consequences ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 19.

LSTM, emotions, opinions, etc. ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 19.

LSTM, emotions, opinions, etc. ~10%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 20.

LSTM, disaster management ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 20.

LSTM, disaster management ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 21.

LSTM, consequences ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 21.

LSTM, consequences ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 22.

LSTM, identification ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 22.

LSTM, identification ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 23.

LSTM, weather ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 23.

LSTM, weather ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 24.

LSTM, Emotions_opinions,_etc. ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

Figure 24.

LSTM, Emotions_opinions,_etc. ~15%. (Star indicates the epoch in which the best balanced model appeared.)

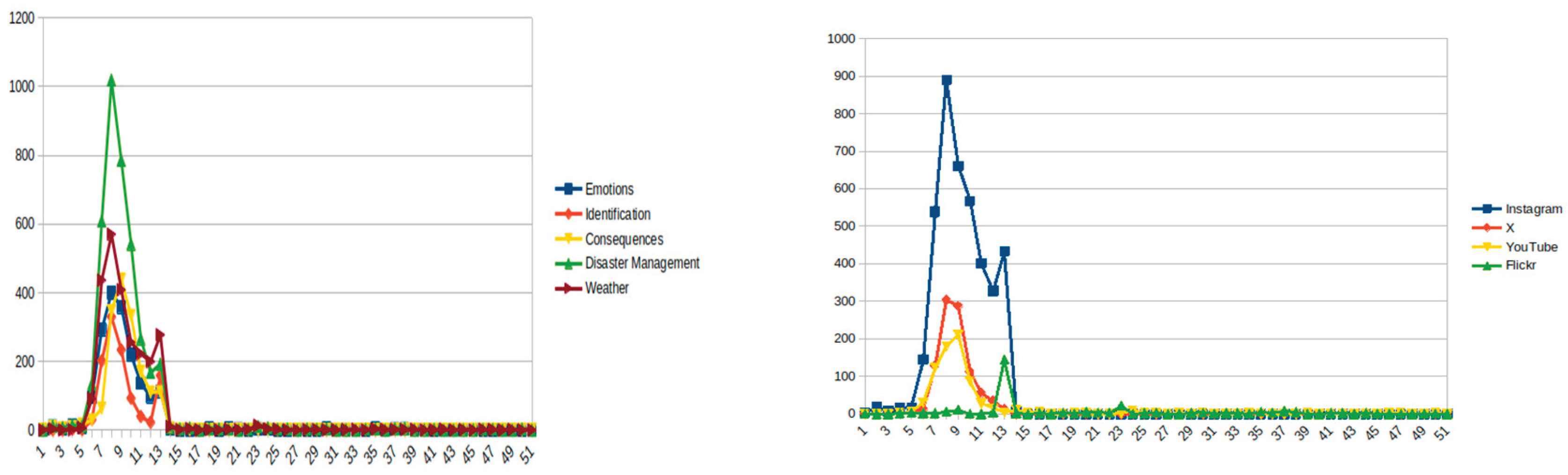

Figure 25.

Frequency of posts per class, divided into 24-h time periods. Right: Frequency of posts per source.

Figure 25.

Frequency of posts per class, divided into 24-h time periods. Right: Frequency of posts per source.

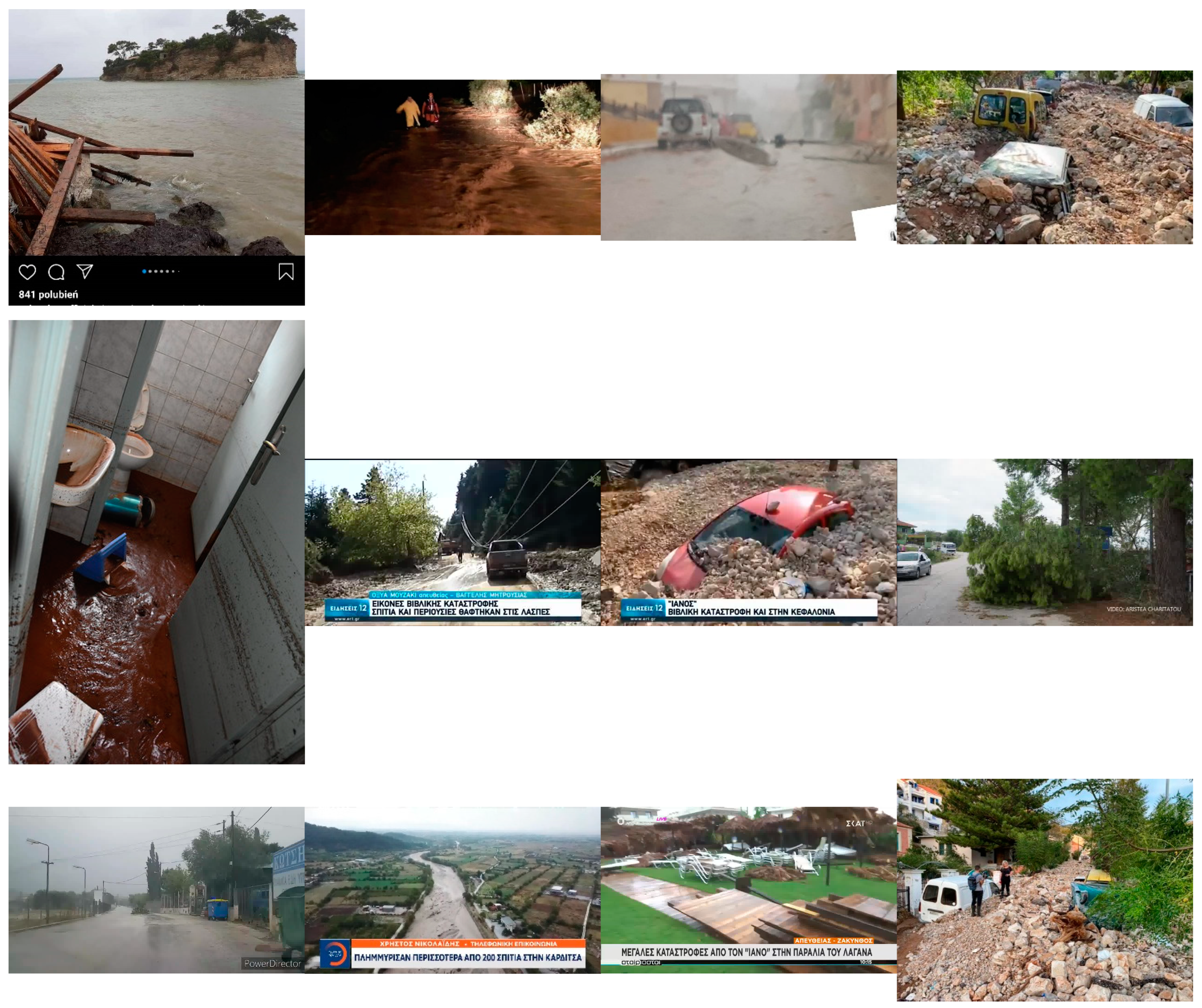

Figure 26.

Indicative photos/video frames that were successfully identified.

Figure 26.

Indicative photos/video frames that were successfully identified.

Figure 27.

Clusters of geocoded locations recognized in text strings of social media posts.

Figure 27.

Clusters of geocoded locations recognized in text strings of social media posts.

Figure 28.

Mapping locations recognized in text strings of Instagram and Flickr posts.

Figure 28.

Mapping locations recognized in text strings of Instagram and Flickr posts.

Table 2.

Parameters, LSTM–RNN.

Table 2.

Parameters, LSTM–RNN.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Epoch |

custom |

| Drop Out |

0.2 |

| Hidden Layers |

100 |

| Batch Size |

1024 |

| Activation |

softmax |

| Dense |

2 |

Table 3.

Parameters, Transformers.

Table 3.

Parameters, Transformers.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Epoch |

custom |

| Learning Rate |

5e-5 |

| Batch Size |

128 |

Table 4.

Train Accuracy and Precision, Validation Accuracy and Precision of LSTM-RNN and Transformers in Both Training Datasets: ~10%, ~15% of the Total Volume.

Table 4.

Train Accuracy and Precision, Validation Accuracy and Precision of LSTM-RNN and Transformers in Both Training Datasets: ~10%, ~15% of the Total Volume.

| Model/Training Dataset |

Train_Acc |

Val_Acc |

Model, Training Dataset |

Train_Acc |

Val_Acc |

| LSTM-RNN 10% Identification |

0.94 |

0.9 |

Transformers, 10% Identification |

0.87 |

0.92 |

| LSTM-RNN 10% Weather |

0.83 |

0.73 |

Transformers, 10% Weather |

0.77 |

0.7 |

| LSTM-RNN 10% Consequences |

0.96 |

0.89 |

Transformers 10% Consequences |

0.87 |

0.84 |

| LSTM-RNN 10% Disaster Management |

0.89 |

0.8 |

Transformers 10% Disaster Management |

0.80 |

0.72 |

| LSTM-RNN 10% Opinions, Comments, Emotions |

0.78 |

0.71 |

Transformers 10% Opinions, Comments, Emotions |

0.81 |

0.71 |

| LSTM-RNN 15% Identification |

0.93 |

0.9 |

Transformers15% Identification |

0.93 |

0.89 |

| LSTM-RNN 15% Weather |

0.91 |

0.83 |

Transformers 15% Weather |

0.87 |

0.8 |

| LSTM-RNN 15% Consequences |

0.93 |

0.85 |

Transformers 15% Consequences |

0.90 |

0.83 |

| LSTM-RNN Disaster Management 15% |

0.94 |

0.85 |

Transformers Disaster Management 15% |

0.87 |

0.8 |

| LSTM-RNN Opinions, Comments, Emotions 15% |

0.76 |

0.78 |

Transformers’ Opinions, Comments, Emotions 15% |

0.78 |

0.78 |

Table 5.

SOTA Metrics of LSTM-RNN After 1 Iteration, Enriching the Training Dataset with the FPs, FΝs.

Table 5.

SOTA Metrics of LSTM-RNN After 1 Iteration, Enriching the Training Dataset with the FPs, FΝs.

| N = 100 |

Pred. Accuracy |

Pred. Precision |

Pred. F1 |

Pred. Recall |

| Identification |

0.94 |

0.73 |

0.81 |

0.91 |

| DM |

0.88 |

0.83 |

0.87 |

0.92 |

| Consequences |

0.94 |

0.90 |

0.86 |

0.82 |

| Weather |

0.94 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| Opinions, comments etc. |

0.89 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

0.81 |

Table 6.

Training, Validation and Prediction Acc for all Models and Ensemble Approach.

Table 6.

Training, Validation and Prediction Acc for all Models and Ensemble Approach.

| N = 150 |

Train Acc |

Validation Acc |

Pred_Acc |

| VGG-19 Fine-tuned |

0.93 |

0.94 |

0.82 |

| ResNet101 fine-tuned |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.82 |

| EfficientNet fine-tuned |

0.94 |

0.93 |

0.69 |

| Ensemble approach |

0.99* |

0.99* |

0.98* |

Table 7.

SOTA Evaluation of Video Frames Classification: Prediction Accuracy.

Table 7.

SOTA Evaluation of Video Frames Classification: Prediction Accuracy.

| Model |

Prediction Accuracy

YouTube Frames, n = 150 |

Prediction Accuracy

Instagram Video Frames, N = 200 |

| VGG-19 fine-tuned |

0.69 |

0.80 |

| ResNet101 fine-tuned |

0.73 |

0.81 |

| EfficientNet fine-tuned |

0.75 |

0.79 |

| Ensemble approach |

Actual: 0.77 |

Actual: 0.82 |

Table 8.

RSVI Summary.

| N of Videos. |

Mean RSVI |

Source |

| 511 |

0.34 |

YouTube |

| 241 |

0.55 |

Instagram |

Table 9.

SOTA evaluation of Location Entity Extraction. One Round of Additions.

Table 9.

SOTA evaluation of Location Entity Extraction. One Round of Additions.

| N = 200 Rows, 476 Cases |

Precision |

Accuracy |

Recall |

F1 |

Specificity |

| LER |

0.88 |

0.85 |

0.93 |

0.9 |

0.58 |

| LER + Geoparsing |

1 |

0.93 |

0.91 |

0.95 |

1 |

Table 10.

Geocoding Evaluation.

Table 10.

Geocoding Evaluation.

| N = 100 |

Accuracy |

| GIS Analysis, conventional geocoding APIs |

0.99 |