1. Introduction

Proteins and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Proteins are essential biomolecules made up of extended amino acid chains that fold into precise three- dimensional shapes that enable their functions. Proteins are crucial in almost every biological process since they act as enzymes and structural components when transporting substances and signaling between cells. The fundamental role of proteins in the brain includes supporting neurotransmission, as well as synaptic plasticity, along with energy metabolism and cell repair functions, which help neurons maintain efficient communication and adapt to various stimuli. Proteins achieve proper function by forming specific shapes guided by their amino acid sequences. The folding mechanism of proteins facilitates their appropriate interactions with other molecules while preserving both cellular efficiency and stability [

9].

The protein folding mechanism operates under strict regulation, but sometimes fails and produces in- correctly folded proteins. Misfolded proteins can emerge from genetic mutations, environmental stress, imbalances in molecular chaperones, or disruptions of the proteostasis network. Misfolded proteins may stop functioning correctly or destabilize and form aggregates that disrupt normal cell processes. Cells use chaperone proteins and degradation pathways to detect misfolded proteins and control their build-up within manageable limits. The failure of the proteostasis network allows misfolded proteins to persist, disrupting normal cellular functions [

9].

Misfolded protein accumulation is a well-documented hallmark feature in various neurodegenerative disorders. Amyloid beta and misfolded tau protein plaques and tangles interfere with neuronal signaling while also activating inflammatory responses in Alzheimer’s disease. In Parkinson’s disease, aggregates of misfolded alpha-synuclein, which develop into Lewy bodies, damage dopamine-producing neurons. Huntington protein (HTT) with an abnormal polyglutamine expansion forms toxic aggregates that damage neuronal function, leading to Huntington’s disease. The misfolding of the protein TDP- 43 or SOD1 will cause the key pathological events that drive ALS and FTD, both of which cause progressive motor and cognitive degeneration. Prion diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, have a characteristic pathogenic mechanism in which misfolded proteins propagate between proteins, resulting in faster brain damage [

39].

In particular, a recent experimental study in mice [

41] using anti-TRPV1 beta-synuclein nanoparticles (ATB NP) demonstrated that direct disaggregation and removal of misfolded alfa-synuclein aggregates in the substantia nigra led to a clear reversal of Parkinsonian motor symptoms. This finding provides important biological validation that removal of pathological proteins, even in advanced stages, can restore neural function, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of direct interventions targeting protein aggregates. Currently, no treatment can cure neurodegenerative diseases.

Medical interventions can be broadly divided into two categories: Neurodegenerative disease treatment methods include pharmacological treatments along with non-pharmacological approaches that use external stimulation.

The primary target of pharmacological treatments is to manage disease symptoms while slowing the progression of the disease. While Levodopa offers temporary relief for Parkinson’s disease patients by raising dopamine levels it fails to halt the progression of neurodegeneration [

28] [

19]. Cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists show minimal cognitive benefits while failing to stop protein aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease treatments [

8] [

23]. Present research targets molecular chaperones along with RNA-based therapies and gene editing methods to prevent toxic protein misfolding while enhancing the removal of detrimental protein aggregates. Immunotherapy offers promising results for Alzheimer’s disease treatment through antibodies targeting misfolded proteins while researchers examine anti-amyloid medications like aducanumab and lecanemab [

14] [

29] [

22].

Researchers are examining external stimulation techniques like electromagnetic and mechanical waves to affect neural functions and counteract disease progression without the use of drugs. These include but not limited:

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) serves as a recognized surgical intervention focusing mainly on motor symptoms during the advanced phases of Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Electrodes implanted in the sub- thalamic nucleus (STN) or globus pallidus internus (GPi) regions deliver electrical impulses to modify dysfunctional neural circuits. DBS treatment leads to significant reductions in tremors and rigidity while improving bradykinesia and motor complications from levodopa which enables patients to lower their medication dosage for better life quality [

34]. Nonetheless DBS has its share of disadvantages. Surgical complications and neuropsychiatric effects including depression or apathy along with cogni- tive decline are postoperative risks which older patients or those with existing cognitive deficits face. APOE epsilon 4 and GBA1 mutations among genetic factors can heighten these risks [

1].

The use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) represents an experimental treatment currently being developed to adjust memory and cognitive pathways in order to decelerate or reverse the progression of cognitive deterioration. DBS is an established treatment for Parkinson’s Disease but researchers continue to study its application for Alzheimer’s Disease where it is used in early or mild cases. Investigations into deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer’s Disease focus primarily on targeting the fornix as the hippocampus’s major output tract and the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) for its role in cholinergic signaling. A number of small clinical trials along with meta-analyses have shown minor enhancements in memory function and attention as well as better functional brain connectivity for patients treated with fornix DBS [

25] [

11]. The results of treatments differ significantly across cases and the cognitive improvements patients experience usually fail to persist over extended periods. The main limitations of this procedure consist of its invasive nature, inconsistent patient responses and absence of established protocols and extensive randomized studies. Experts continue to worry about the risk of delirium, seizures or worsening neurodegeneration in sensitive brain pathways during treatments [

27]. DBS in AD treatment remains in the preclinical and early clinical trial stages requiring stronger evidence for clinical implementation.

The non-invasive neuromodulation technique Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (LIFU) presents promis- ing therapeutic benefits for neurodegenerative conditions through early clinical and preclinical trials in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). LIFU delivers pulsed acoustic energy to targeted brain regions, offering two principal benefits in AD: LIFU temporarily opens the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and directly modulates neural activity within memory-related brain circuits including the hippocampus and en- torhinal cortex. Research shows LIFU facilitates amyloid-beta removal from the brain and stimulates new neuron growth and slightly enhances cognitive function both with drugs such as aducanumab and when used independently [

24] [

31]. LIFU stands apart from Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) due to its non-invasive nature which lowers surgical complication risks. However, challenges remain: Because treatment responses differ widely treatment outcomes can vary because sonication protocols lack stan- dardization and inaccurate parameter calibration may produce off-target effects or tissue damage [

13]. LIFU remains experimental but shows great promise as an AD treatment tool when used alongside pharmacological therapies.

The combination of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRgFUS) presents a new non-invasive surgical approach to treat Parkinson’s Disease (PD) in pa- tients who cannot undergo deep brain stimulation (DBS). HIFU uses precisely focused ultrasound waves to ablate specific brain structures like the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus or the globus pallidus internus (GPi) which results in tremor suppression and motor symptom relief without surgical incisions or implanted devices. Ablation using focused ultrasound has demonstrated fast relief from tremors and rigidity in clinical research while receiving FDA approval for unilateral tha- lamotomy treatment in Parkinson’s Disease patients. Patients benefit from faster recovery periods and lower infection risks while avoiding implanted hardware and extended programming needs. However, HIFU has limitations: The one-sided effect of HIFU makes it inappropriate for bilateral treatment needs while presenting potential irreversible side effects that include gait problems, paresthesia, or speech difficulties in certain patients [

37]. Long-term data about cognitive outcomes and symptom progression are still limited particularly when compared with DBS which provides adjustable stimula- tion. MRgFUS-HIFU shows great potential as a non-invasive therapy for specific PD patients facing medication-refractory tremor although its usage is restricted by anatomical limitations and regulatory as well as technological barriers.

Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) represents an innovative non-invasive brain mod- ulation method that delivers weak sinusoidal currents at specific frequencies to synchronize disrupted neural oscillations particularly in the gamma ( 40 Hz) and theta (4–8 Hz) bands which are affected in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The MIT lab led by Li-Huei Tsai achieved a significant breakthrough by showing that gamma-frequency stimulation through sensory entrainment can reduce amyloid-beta plaques and enhance both microglial activity and synaptic function in AD mouse models [

17]. Re- searchers have now applied non-invasive transcranial electrical stimulation to this method which is currently being tested in early-phase human trials (MIT Picower Institute Review, 2024). The ad- vancements from these studies have initiated fresh clinical research investigations into gamma-tACS as a new therapeutic approach. Through their detailed review [

10] demonstrated how tACS has the potential to restore neural synchrony in Alzheimer’s Disease which may lead to improved cognitive functions including attention and memory capacity. TACS research shows potential but continues to struggle with issues like brief treatment effects and inconsistent patient responses along with miss- ing standardized protocols [

2] [

36]. The non-invasive nature of tACS combined with its potential for home usage provides strong reasons for its wider implementation in the early treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Physical stimulation methods utilizing mechanical or electromagnetic stimuli are increasingly accepted because they produce disease-modifying effects through neurophysiological and molecular pathway targeting. Our proposed approach builds upon existing knowledge by using a resonance-frequency- targeted method which selectively activates misfolded protein aggregates through specific vibrations for their denaturation process.

2. Protein Resonance Frequencies

The resonance frequency of a system is its natural vibration mode that is preferentially excited by an external periodic force. When the frequency of the external force aligns with this natural vibrational mode, energy transfer into the system is maximized, resulting in a significantly enhanced oscillatory amplitude. This physical phenomenon is observed across a broad range of systems, from macroscopic mechanical assemblies to interactions at atomic and molecular scales.

In the context of proteins, the resonance frequency denotes the characteristic vibrational modes as- sociated with their molecular structure. These modes arise from the dynamic interactions among the constituent atoms and molecular subgroups governed by parameters such as atomic mass, bond stiffness, and overall conformational topology of the protein.

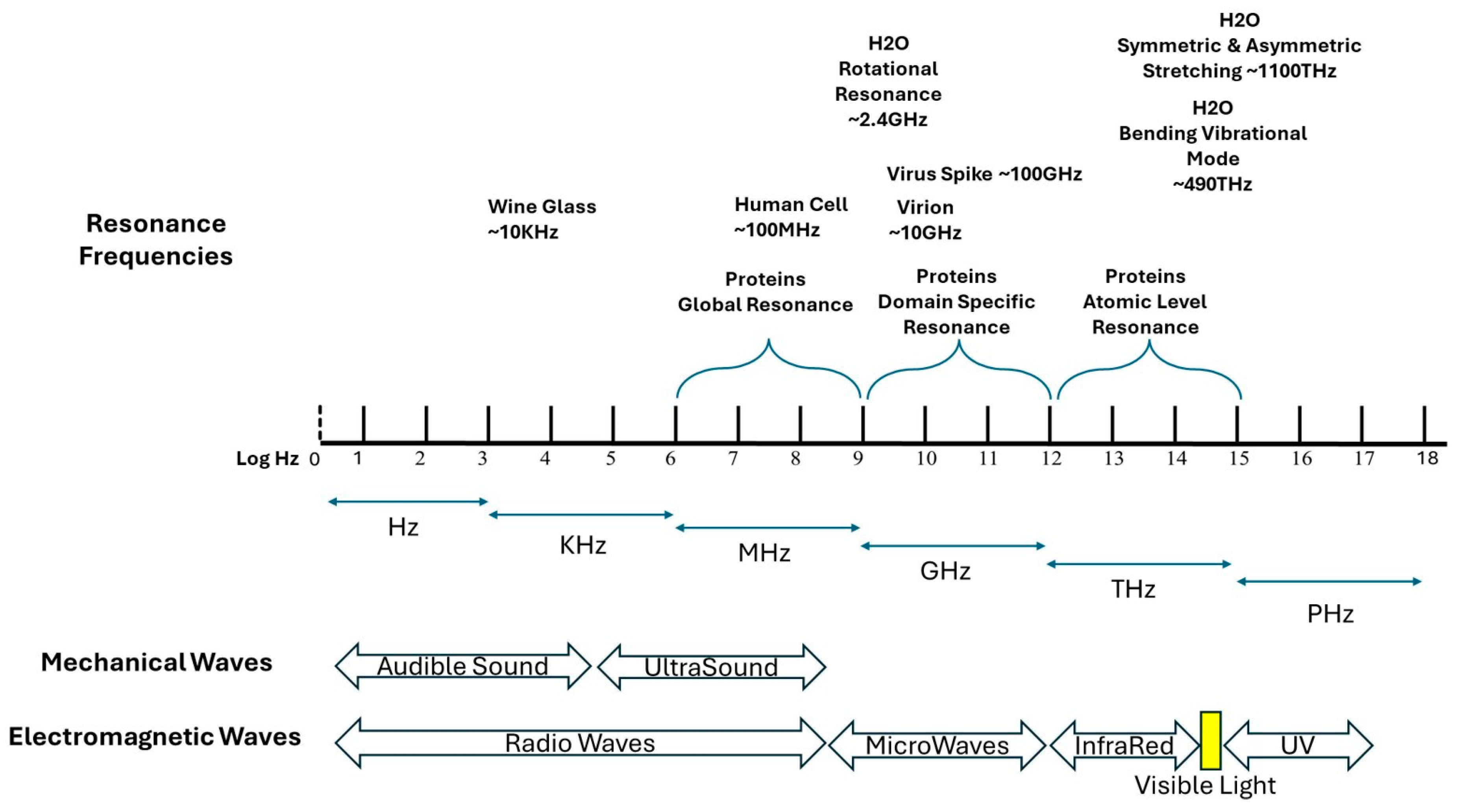

Figure 1.

Frequency scale of mechanical and electromagnetic vibrations. Resonance Frequencies for Viruses, proteins, water, and Human Cells.

Figure 1.

Frequency scale of mechanical and electromagnetic vibrations. Resonance Frequencies for Viruses, proteins, water, and Human Cells.

Proteins, being complex macromolecules, exhibit resonance at multiple levels:

Global resonance (Low-frequency vibrations, megahertz range): Protein structures experience these low-frequency vibrations throughout their entire structure. The global protein dynamics encompasses domain movements as well as loop flexibility and cavity breathing functions because these motions enable enzymatic reactions and allosteric control.

Domain-Specific Resonance (Intermediate-Frequency Vibrations, Gigahertz Range): Specific struc- tural elements like alpha-helices, beta-sheets, and folded domains are sites where these vibrations occur. These elements enhance protein stability and bio-molecular interactions that enable different protein regions to move synchronously.

Atomic-Level Resonance (High-Frequency Vibrations, Terahertz Range): - Vibrations happen at the level of individual chemical bonds and side-chain torsional movements. - Protein folding and functionality depend on hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions and vibrational movements [

43].

Resonance Frequency Changes in Misfolded Proteins

The protein resonance frequencies or natural vibration modes, vary significantly for different protein molecular 3D structures even though they are made of similar sets of amino acids as their elementary chemical building blocks. [

33] These vibrations occur due to the forces between atoms and molecular groups within the protein. Misfolded versions of proteins, such as alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and Tau in Alzheimer’s disease, should exhibit altered resonance frequencies due to changes in their structural conformation. While certain secondary structure elements, such as beta-sheets, may retain similar dimensions—often around 4.7 angstroms between adjacent beta-strands—this does not mean that their resonance frequencies remain unchanged. The overall three-dimensional organization of these sheets within the misfolded protein is different from that of the properly folded form. Misfolding leads to distinct packing arrangements, altered interatomic forces, and variations in intramolecular hydrogen bonding, which are expected to influence the vibrational modes at different scales.

One concern that could be raised is that mechanical or dipolar oscillations might not be sufficiently distinct between native and misfolded proteins to enable selective targeting. However, evidence from spectroscopy, and neutron scattering suggests that proteins do exhibit characteristic vibrational modes influenced by their structure, interactions, and aggregation state [

32]. While most observed frequencies are associated with high-frequency bond-level vibrations rather than whole-protein oscillations, the hypothesis underlying this approach is that misfolded aggregates, due to their altered structure and mechanical properties, may exhibit distinct low-frequency vibrational modes. These shifts could be leveraged for selective excitation through finely tuned external stimuli.

Additionally, the increased rigidity and altered hydrogen bonding networks observed in amyloid fibrils and other misfolded aggregates suggest that their vibrational response may differ significantly from that of their native counterparts [

43] [

6]. Techniques such as normal mode analysis (NMA) and quasi- harmonic approximations have been used to explore these vibrational behaviors in molecular dynamics simulations, providing computational insights that complement experimental findings.

Nonetheless, challenges remain in achieving selective excitation, given that broadband oscillations in biological environments may lead to background excitation of multiple proteins. The working hypothesis is that, through fine-tuning of excitation parameters (pulse duration, modulation, and energy absorption characteristics), it may be possible to enhance selectivity for misfolded proteins. Future experimental validation is needed to substantiate these assumptions and refine the methodology for practical applications.

3. Determining the Resonance Frequency of Misfolded Proteins

Protein resonance frequencies depend on their structural attributes which include vibrations occurring at global, domain-specific, and atomic levels. The resonance frequencies range, from megahertz to terahertz, as function of the molecular mass, bonding interactions, and conformational dynamics. Typically, proteins exhibit natural vibration modes from megahertz to gigahertz as their relatively small size constrains their vibrational spectrum. Given their complex macromolecular architecture, proteins feature multiple resonance modes that arise from distinct organizational levels. [

43]

Fortunately, the first 70 natural vibration modes have already been determined for more than 100,000 proteins whose 3D molecular structures are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [

32] [

7]. The file containing these frequencies is available upon request. For any protein or misfolded version not available in the previously mentioned file, we will first need to determine its 3D structure, if not available in the PDB [

7] or through Google AlphaFold [

18], followed by the determination of its resonance frequencies.

3.1. Identification of the Misfolded Proteins Three-Dimensional Structure

The methodology to determine the resonance frequencies of misfolded proteins typically starts with the precise mapping of the protein’s three-dimensional structure using techniques like Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM), X-ray Crystallography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). Cryo-EM is especially well-suited for the task, given its capability to resolve high-definition, three-dimensional (3D) molecular architectures of proteins in their native conformation—including those susceptible to aggregation, such as alpha-synuclein (linked to Parkinson’s disease) and Tau (implicated in Alzheimer’s disease). [

20]

3.2. Theoretical Estimation via Computational Modeling

Given the protein structural data, the four most used approaches to determine the theoretical resonance frequencies are:

3.2.1. Mass-Spring Model

Approach: Represents molecules as networks of masses (atoms or residues) connected by springs (bonds) [

5].

Energy Minimization: Typically involves minimizing potential energy to find the equilibrium positions before analyzing vibrations.

Computational Complexity: Low; suitable for large systems due to its simplicity.

Precision: Provides a basic understanding of molecular vibrations but lacks detailed atomic interac- tions.

3.2.2. Normal Mode Analysis (NMA)

Approach: Analyzes the harmonic oscillations around a molecule’s equilibrium structure by solving the eigenvalue problem of the Hessian matrix (second derivatives of the potential energy) [

6].

Energy Minimization: Requires prior energy minimization to ensure analysis around a stable equilib- rium.

Computational Complexity: Moderate; involves matrix diagonalization, which can be computationally demanding for large systems.

Precision: Captures collective motions effectively but is limited to small, near-equilibrium fluctuations.

3.2.3. Gaussian Network Model (GNM)

Approach: A coarse-grained version of the mass-spring model that represents the protein structure as a network of nodes (usually C alpha atoms) connected by springs if they are within a certain cutoff distance [

4].

Energy Minimization: Assumes the structure is already near its equilibrium; focuses on fluctuations around this state without explicit energy minimization.

Computational Complexity: Low; due to its coarse-grained nature and simplified interactions.

Precision: Efficiently predicts global motions and has been shown to correlate well with experimental data, sometimes outperforming more detailed MD simulations in capturing certain dynamics.

3.2.4. Molecular Dynamics (MD)

Approach: Simulates the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system by numerically solving New- ton’s equations of motion for all atoms [

20].

Energy Minimization: Often involves an initial energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes or unfavorable interactions, but the simulation itself explores a wide range of conformations beyond local minima.

Computational Complexity: High; due to the need to calculate forces and integrate motions over many time steps, especially for large systems or long simulations.

Precision: Provides detailed insights into molecular behavior, including large conformational changes and non-harmonic motions, offering a comprehensive view of molecular dynamics.

Mass-Spring Model vs. GNM: Both simplify the system into a network of masses and springs, but GNM offers a more refined approach by focusing on the topology of interactions and has been shown to align closely with experimental data [

4].

NMA vs. MD: While NMA provides insights into the intrinsic, collective motions of proteins around their equilibrium states, MD simulations offer a dynamic and detailed trajectory of molecular motions over time, capturing both small and large-scale conformational changes [6, 20].

3.3. Empirical Validation Through Spectroscopy

The vibrational dynamics of proteins across low-frequency ranges associated with collective molecular motions can be examined through Neutron Scattering (Inelastic Neutron Scattering, INS), Brillouin Scattering, and Microwave Spectroscopy as powerful investigative methods.

INS functions as a spectroscopic method for identifying protein vibrations between MHz and GHz frequencies, which helps to reveal how proteins undergo large-scale shape changes and how they manage energy loss [

42].

Brillouin Scattering detects protein structural oscillations through analysis of scattered light frequency shifts by acoustic phonons to study molecular mechanical characteristics and elastic changes [

15].

Microwave Spectroscopy examines molecular excitations at GHz frequencies to identify unique reso- nances that indicate dipolar interactions and significant domain movements in protein structures [

21].

The techniques mentioned above demonstrate their utility in distinguishing between the vibrational patterns of properly folded proteins and those that are misfolded, which offers potential for selective targeting in medical treatments [15, 21, 42].

4. Cellular Clearance Mechanisms in the Brain for Removing Denatured Proteins

The primary objective of the resonance-frequency-targeted HIFU or HIFMW approach is to destabilize large misfolded protein aggregates into monomeric or disorganized forms, which the brain’s natural clearance systems can then efficiently remove. Several endogenous pathways play key roles in main- taining proteostasis by clearing misfolded, damaged, or aggregated proteins.

Key clearance pathways include [

40] 1. Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS): Misfolded proteins are tagged with ubiquitin, targeting them for enzymatic degradation in the proteasome.

Autophagy-lysosomal pathway: Cellular debris and protein aggregates are encapsulated in au- tophagosomes that fuse with lysosomes for degradation by hydrolytic enzymes.

Molecular chaperones: These assist in correct protein folding and, in cases of persistent misfolding, direct the protein to degradation pathways. In particular, the chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) pathway, involving HSC70 and LAMP2A, plays a key role in identifying and transporting destabilized proteins into lysosomes.

Glymphatic system: A fluid-based clearance mechanism that removes extracellular waste—including misfolded proteins—from the interstitial space via cerebrospinal fluid.

Microglial phagocytosis: Microglia engulf and degrade extracellular protein aggregates and debris, reducing neurotoxicity.

4.1. Experimental Validation of Heat-Activated Clearance: The ATB NPs Approach

A recent study [

41] employing Anti-TRPV1–beta-synuclein nanoparticles activated by near-infrared light (ATB NPs with NIR) demonstrated that direct activation of dopaminergic neurons, combined with targeted disruption of alfa-synuclein aggregates, could restore motor function in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

In this system, gold-based nanoparticles are conjugated with: • an antibody targeting TRPV1 to anchor onto dopaminergic neurons, • beta-synuclein peptides to bind and destabilize alfa-synuclein fibrils, • and boronate ester linkers that release these peptides upon localized heating via NIR light.

The NIR-induced heat both reactivates neurons via TRPV1 channels and triggers the brain’s en- dogenous CMAz pathway by activating HSC70, which recognizes thermally destabilized proteins and transports them into lysosomes via LAMP2A for degradation. This study provides compelling experi- mental confirmation that once a misfolded protein is rendered unstable or exposed, the brain’s natural clearance systems are capable of completing its removal.

While effective in rodents, the translation of the ATB NP system to human therapy faces key limita- tions, such as the poor penetration depth of NIR light through human cranial tissue, and the need for stereotactic intracerebral injection and potentially invasive optical fiber placement.

4.2. Implications for the Resonance-Frequency-Based Approach

The findings from the ATB NP study support a central hypothesis of this paper: that destabilizing misfolded proteins is sufficient to initiate their removal by the brain’s own mechanisms. Importantly, in the proposed resonance-frequency- targeted method, heat is generated intrinsically by the protein itself, as it absorbs vibrational energy at its specific natural frequency.

This localized thermal excitation could:

Physically disrupt misfolded aggregates;

Expose structural motifs that activate HSC70 recognition;

Trigger CMA and lysosomal degradation as observed in the ATB NP study.

Thus, even without injecting exogenous peptides or relying on antibody targeting, the selective vi- brational excitation of pathological proteins in our approach may achieve both disaggregation and clearance, non-invasively and with higher molecular specificity.

5. Ultrasound and Microwaves

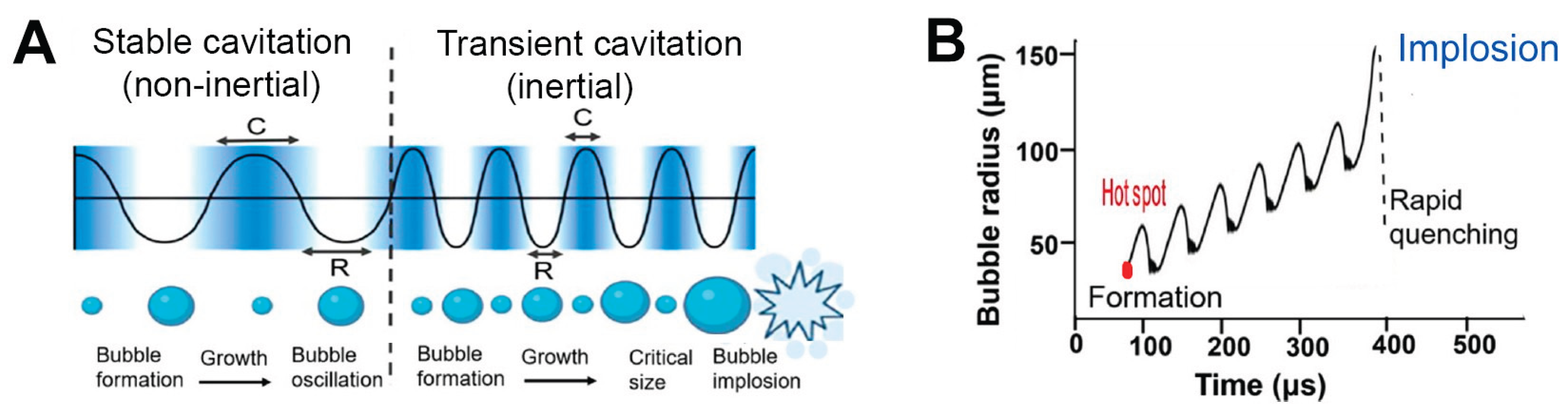

Ultrasound describes mechanical waves that exceed the human hearing range with frequencies above 20 kHz and finds primary applications in medical imaging and therapeutic interventions. The propa-gation of these waves through tissues happens through particle oscillations within the medium which makes them ideal for applications that demand mechanical contact with biological structures. Elec- tromagnetic waves in the range of 300 MHz to 300 GHz make up microwaves. Microwaves propagate through space without needing a medium by interacting with matter through electromagnetic fields which mainly affect dipole rotation and ionic conduction.

Ultrasound and microwaves play significant roles within medical applications. Diagnostic imaging utilizes ultrasound extensively while its higher intensity application targets therapeutic interventions like lithotripsy and tumor ablation. Medical applications of microwaves extend to hyperthermia cancer treatments and non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. While both modalities can deposit energy into biological tissues, their modes of action differ fundamentally: Ultrasound generates energy through mechanical means while microwaves provide electromagnetic energy. Therapeutic ultrasound creates cavitation (see

Figure 2) which involves the formation and destruction of microbubbles in a liquid environment through alternating pressure waves. The process produces localized high temperatures and strong shear forces thus improving therapeutic outcomes while creating safety risks when precise control becomes essential [

35].

Our proposed method does not rely on cavitation as its primary operational mechanism. Our method employs ultrasound and microwaves to activate misfolded proteins like alpha-synuclein and Tau aggre- gates by matching their natural resonance frequencies through non-thermal vibration. The proposed strategy uses mechanical or electromagnetic resonance to disrupt targets while intentionally preventing thermal damage to healthy tissues. Our ultrasound techniques maintain operation below safe pressure limits to prevent cavitation while ensuring a non-thermal setting suitable for precise molecular. [

3] [

40].

6. Proposed Mechanism of Action

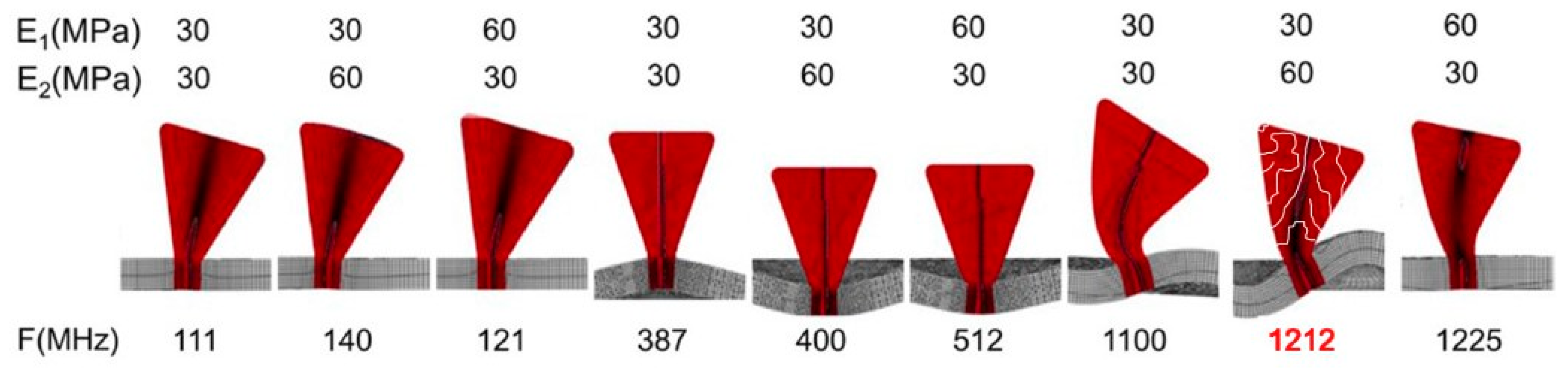

Emerging evidence supports the hypothesis that biomolecules can be selectively disrupted by externally applied vibrational energy when tuned to their specific resonance frequencies. In this context, misfolded proteins—particularly alpha-synuclein and tau—exhibit altered vibrational modes as a result of their aberrant three-dimensional structures. This foundational principle has been successfully demonstrated in recent studies targeting viral particles through frequency-matched vibrational disruption (see

Figure 3) [

41].

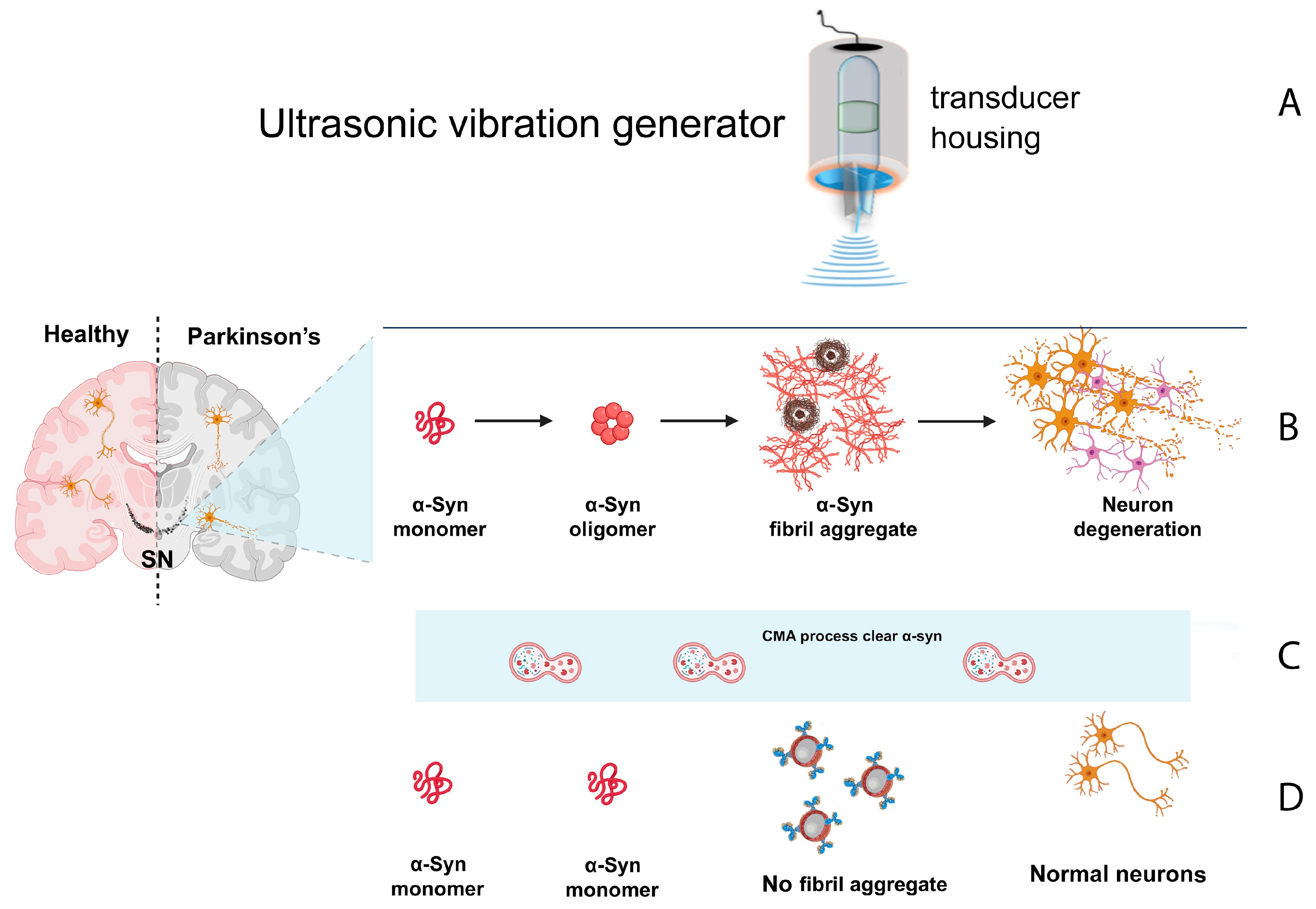

Our proposed therapeutic approach expands upon this principle by employing High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) or High-Intensity Focused Microwave (HIFMW) to selectively target misfolded protein species involved in neurodegenerative diseases. Unlike methods that solely focus on late- stage aggregates such as Lewy bodies, our approach is designed to act across the entire pathological cascade—from early misfolded monomers to intermediate oligomers and mature inclusions.

The

Figure 4 visually illustrates the progression of alpha-synuclein pathology, from misfolded monomeric species to oligomeric assemblies, Lewy bodies, and ultimately neuronal degradation. It also highlights the intervention points of our proposed method, showing how HIFU and HIFMW can target and destabilize misfolded monomers before aggregation, as well as disassemble existing fibrils and inclusions.

This broad-spectrum action offers a comprehensive strategy for minimizing the pathological burden of these proteins.

Importantly, once the misfolded proteins absorb energy and become thermally destabilized at their specific resonance frequencies, they are rendered more visible and accessible to the brain’s intrin- sic clearance systems. In particular, heat-activated pathways such as chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) and lysosomal degradation are triggered. This results in the breakdown and removal of frag- mented protein aggregates—whether they originated as monomers, oligomers, or Lewy bodies—via lysosomal digestion and proteasomal processing. The final metabolic products, including short pep- tides and amino acids, are naturally recycled or cleared by the organism, completing a full biochemical cleanup of the pathological residues.

Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) can be employed in combination with the resonance- frequency-targeted approach proposed herein to enhance the clearance of fragmented or denatured mis- folded proteins. Following selective disruption of pathological protein aggregates by resonance-based techniques (HIFU or HIFMW), applying tACS could stimulate endogenous neural oscillations and enhance neural network activity associated with glymphatic function and autophagic pathways. Con- sequently, the combined strategy of resonance-induced disruption and subsequent neuromodulation via tACS has the potential to significantly improve the efficiency of cellular clearance mechanisms, further reducing protein accumulation and enhancing therapeutic outcomes in neurodegenerative diseases.”

In this context, it is important to consider the manner in which energy is delivered. Focused energy deposition—whether via HIFU or HIFMW—enables the targeting of specific pathological regions while minimizing the generation of systemic thermal byproducts. This localized stimulation offers two key advantages: (1) it reduces the risk of damaging healthy tissue and (2) it produces a manageable volume of denatured proteins for clearance, aligning with the brain’s limited capacity to process molecular debris.

Conversely, a more generalized “bath” approach—where energy is diffusely applied across broader brain regions—may overwhelm the endogenous clearance systems by generating a large volume of denatured proteins simultaneously. Although the use of resonance frequency ensures that only misfolded proteins are affected, regardless of whether energy is delivered focally or diffusely, a bulk release of unfolded material could exceed the capacity of lysosomal and proteasomal pathways. This could result in incomplete clearance, potential reaggregation, or unintended inflammatory responses. For this reason, our methodology favors a progressive, spatially controlled stimulation to allow real-time assessment of both protein disruption and the brain’s capacity for cleanup.

It is also crucial to emphasize that not all monomers are pathological; only the misfolded conform- ers pose a threat. Our technique aims to selectively excite these disease-associated species without disturbing the functional ones, taking advantage of their altered vibrational characteristics.

This multipronged intervention model carries significant therapeutic implications. If the underlying cause of misfolding is a singular initiating event—as suggested by the prion-like propagation the- ory—then full clearance of misfolded species might interrupt the pathological cycle and potentially constitute a functional cure. In contrast, when misfolding arises from continuous genetic mutations or chronic dysfunction in protein homeostasis, the proposed method could serve as a maintenance ther- apy. By periodically disrupting and clearing misfolded species, it may help preserve neuronal integrity over time.

Ultimately, this approach integrates targeted disruption with endogenous cleanup mechanisms, offering a non-invasive strategy that shifts the treatment paradigm toward proactive molecular sanitation rather than symptomatic management.

7. Challenges and Considerations

Frequency Determination: Identifying resonance frequencies of misfolded protein aggregates in living organisms proves difficult because biological tissues exhibit complex properties.

Safety: Research must evaluate how focused ultrasound/microwave at specific frequencies affects both brain function and surrounding tissues.

Technical Limitations: HIFU/HIFMW technology requires modifications to meet precision stan- dards.

Regulatory Approval: New medical technologies need to be tested thoroughly and receive regu- latory approval before they can be used clinically.

Uncertainty in Clearance Origin and Capacity: One of the most profound challenges lies in our limited understanding of the brain’s capacity to clear denatured protein material. There is increasing evidence [

26] suggesting that neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s may originate, in part, from defects in autophagic or lysosomal clearance systems. If the pathological accumulation of misfolded proteins results from an impaired cleanup mechanism, then relying on this same system to eliminate additional denatured proteins produced by the therapy may be ineffective—or even counterproductive. In extreme scenarios, accelerated removal attempts could exacerbate the burden on a compromised system, potentially accelerating disease progression.

However, it is important to note that once misfolded proteins are mechanically disrupted at their resonance frequency, their resulting fragments differ structurally from the original aggregates. These new fragments—ranging from short peptides to free amino acids—may be more readily recognized and processed by the brain’s cleanup systems.

Furthermore, the heat generated by vibrational disruption may serve a dual role: not only does it denature pathological aggregates, but it also acts as a trigger for heat-sensitive clearance pathways such as chaperone-mediated autophagy and macroautophagy. These processes are not typically activated by the mere presence of misfolded proteins, but are responsive to local thermal stress. This temperature-dependent activation could provide an additional layer of efficacy to the proposed therapy, even in patients whose baseline proteostatic systems are partially compromised.

Overlapping Pathologies: A broader question arises from the observation that many neurodegen- erative diseases share common hallmarks, such as the accumulation of misfolded proteins (e.g., alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s, tau in Alzheimer’s, and TDP-43 in ALS). If a fundamental defect in protein clearance underlies these disorders, it raises the possibility of concurrent or sequential disease processes. Clinical and post-mortem studies have indeed revealed mixed pathologies in many patients, suggesting that protein clearance dysfunctions may not be disease-specific. Un- derstanding the selectivity, capacity, and hierarchical behavior of protein cleanup systems will be essential to ensuring targeted and effective intervention.

8. Conclusion

The proposed strategy targets neurodegenerative disorders with a non-invasive method that uses High- Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) or Microwaves (HIFMW) to destroy misfolded protein aggregates through resonance frequency tuning. This technology targets and decomposes harmful proteins through their specific vibrational signatures but leaves healthy proteins and adjacent tissues untouched.

However, this approach faces several relevant challenges. The technical challenge persists in identi- fying the specific resonance frequencies of pathological protein conformers within complex biological matrices. Therapy effectiveness requires exact energy delivery and depends on the brain’s ability to eliminate generated fragments safely. Many neurodegenerative diseases develop because of fundamen- tal issues in autophagic and lysosomal clearance systems which suggests that the cleanup mechanisms themselves are impaired in patients who require them most.

Despite these challenges, the proposed method introduces a promising shift toward proactive molecular sanitation. We recognize the high-risk, high-reward nature of this strategy and strongly encourage crit- ical evaluation, collaboration, and feedback from the broader scientific community to refine, validate, and realize its clinical potential.

9. Suggested Treatment Development Roadmap

9.1. Stage 1 – Proof of Concept (POC)

The objective of this POC is to demonstrate the feasibility of selectively denaturing misfolded proteins without affecting normal proteins or surrounding tissue.

9.1.1. Task I: Protein Domain Definition

Define the structural variations of both normal and misfolded versions of alpha-synuclein and Tau proteins that need to be analyzed.

Establish criteria to classify structural deviations that could influence resonance properties.

9.1.2. Task II: 3D Structure Identification

Perform a comprehensive search for available 3D structural data of the selected protein variants and their natural vibrational modes.

If reliable 3D structures are unavailable, use Cryo-EM (Cryogenic Electron Microscopy) to determine their structures.

9.1.3. Task III: Theoretical Natural Vibration Modes Calculation

9.1.4. Task IV: Experimental Validation of Normal Modes

Use Neutron or Brillouin Scattering or Microwave spectroscopy to determine the natural vibrational frequencies of misfolded and normal proteins, using theoretical calculations as reference.

Employ neutron scattering spectroscopy to enhance precision in vibrational mode identification,

particularly for amyloid structures.

Compare computational predictions with experimental results to refine the resonance frequency model.

9.1.5. Task V: In Vitro Denaturation Study

Conduct experiments in vitro under pH and ionic conditions that closely mimic the extracellular environment of the human brain, considering neurochemical shifts typical in individuals over 30-40 years old. Sample preparation may involve post-mortem human brain tissue, patient-derived neuronal cultures, brain organoids, or recombinant misfolded protein aggregates, depending on feasibility and experimental needs.

Apply High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) or High-Intensity Focused Microwaves (HIFMW) at the experimentally determined frequencies.

Evaluate the denaturation efficiency of misfolded proteins while ensuring minimal impact on normal proteins and surrounding environments.

Utilize circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to confirm protein denaturation.

Perform Western blot analysis and mass spectrometry to verify structural degradation and fragmen- tation of misfolded proteins.

9.2. Stage 2: Preclinical Animal Studies

Objective: Evaluate the safety and efficacy of the method in living models.

Development of Specialized Hardware: Customize HIFU and HIFMW devices for testing in living organisms.

Cell Culture Testing: Monitor the degradation of target proteins and the activation of intracellular clearance pathways (proteasome, autophagy).

Small Animal Experiments: Use genetically modified mice to model advanced stages of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

Thermal Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Measure heat distribution to confirm precise targeting.

Safety Analysis: Examine potential collateral damage to healthy tissues.

Parameter Refinement: Adjust frequencies, intensity, and exposure time to optimize selectivity.

9.2.1. Stage 3: Phase 1 Clinical Trials

Objective: Test safety and initial effects in human patients. • Preclinical Regulatory Approval: Submit documentation to regulatory agencies (FDA, ANVISA, EMA).

Clinical Protocol Development: Define patient inclusion criteria, treatment parameters, and efficacy measurements.

Trials with Advanced Stage Patients: Focus on patients in advanced stages of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s to better observe potential improvements.

Monitoring of Responses: Use neuroimaging and biomarker tests to assess treatment response.

9.2.2. Stage 4: Phase 2 and 3 Clinical Trials

Objective: Confirm therapeutic efficacy and obtain regulatory approval.

Large-Scale Trials: Multicenter studies involving hundreds of patients.

Comparison with Standard Treatments: Assess results against already approved medications.

Long-Term Monitoring: Evaluate potential adverse effects and the durability of treatment benefits.

Final Device Optimization: Fine-tune the technology before commercial release.

References

- Afshari M, O’Shea SA, Metman LV, Sani S. 2025. APOE carrier status and cognitive out- comes after STN-DBS surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. [CrossRef]

- Agboada D, Zhao Z, Wischnewski M. 2025. Neuroplastic Effects of Transcranial Alternating Cur- rent Stimulation (tACS): From Mechanisms to Clinical Trials. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Bachu VS, Kedda J, Suk I, Green JJ, Tyler B. 2021. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound: A Review of Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 49(9), 1975–1991. [CrossRef]

- Bahar I, Atilgan AR, Demirel MC, Erman B. 1998. Vibrational dynamics of folded proteins: Significance of slow and fast modes in relation to function and stability. Physical Review Letters, 80(12), 2733–2736. [CrossRef]

- Bahar I, Atilgan AR, Erman, B. 1997. Direct evaluation of thermal fluctuations in proteins using a single-parameter harmonic potential. Folding and Design, 2(3), 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Bahar I, Rader AJ. 2005. Coarse-grained normal mode analysis in structural biology. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 15(5), 586–592. [CrossRef]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig, H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research, 28(1), 235–242. [CrossRef]

- Birks J. 2006. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD005593. [CrossRef]

- Branden C, Tooze J. 1999. Introduction to Protein Structure. Garland Science, 2nd ed. ISBN: 978-0815323051.

- Capone D, Guerra A, Rocchi L, Di Lazzaro V. 2024. Using TMS-EEG to assess the effects of neuromodulation techniques: a narrative review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1247104. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary U. 2025. Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques: DBS for Neurological and Psychi- atric Disorders. In Foundations of Brain-Computer Interface Technology (pp. 101–118). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ciechanover A, Kwon Y. 2015. Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp Mol Med 47, e147. [CrossRef]

- Cox SS, Connolly DJ, Peng X, Badran BW. 2024. A Comprehensive Review of Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Parameters and Applications in Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders. Brain Stimulation. [CrossRef]

- Cummings J, Lee G, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Taghva K. 2021. Alzheimer’s disease drug develop- ment pipeline. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions, 7(1), e12179. [CrossRef]

- Cusack S, Doster W. 1990. Temperature dependence of the low frequency dynamics of myoglobin.

-

Nature, 347(6292), 614–617. [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena S, Assaedi E, George T. 2025. Modeling Dementia in Patients with Parkin- son’s Disease Years After Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino HF, Singer AC, Martorell AJ, Rudenko A, Gao F, Gillingham TZ, et al. 2016. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia activity. Nature, 540(7632), 230–235. [CrossRef]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Kalia LV, Lang AE. 2015. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet, 386(9996), 896–912. [CrossRef]

- Karplus M, McCammon JA. 2002. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nature Struc- tural Biology, 9(9), 646–652. [CrossRef]

- Kruk D, Meier R, Ratajczak H, Zimmermann H. 2010. Microwave dielectric relaxation studies of hydrated proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 1804(1), 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Lantz R, Du D. 2019. Vibrational Approach to the Dynamics and Structure of Protein Amyloids. Molecules, 24(1), 186. [CrossRef]

- Lipton S. 2006. Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: Memantine and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 5, 160–170. [CrossRef]

- Mehta RI, Ranjan M, Haut MW. 2024. Focused ultrasound for neurodegenerative diseases. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America, 32(1), 101–117. [CrossRef]

- Mello JS, Bechara GI, Aguiar PHP. 2025. Effectiveness of DBS as a treat- ment for Alzheimer’s disease: Meta-analysis. Deep Brain Stimulation, 4(1), 20–32. [CrossRef]

- Menzies FM, Fleming A, Rubinsztein DC. 2015. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(6), 345–357. [CrossRef]

- Myers MH, Hossain G. 2024. Advances in non-invasive brain stimulation techniques for dementia: Comparative perspectives on tDCS, TMS, and LIFU. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 18, 1524097. [CrossRef]

- Nutt JG. 2008. Levodopa therapy for Parkinson’s disease: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacody- namics. Movement Disorders, 23(S3), S531–S541. [CrossRef]

- Panza F, Lozupone M, Logroscino G, Imbimbo BP. 2019. A critical appraisal of amyloid- beta-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology, 15(2), 73–88. [CrossRef]

- Park KW, Baik K, Lee S, Lee CN. 2025. MRgFUS pallidothalamic tractotomy following GPi DBS in a patient with refractory hemichorea: A case report. Brain Stimulation, 18(2), 210–213. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Han Y, Wang L. 2024. Opening neural gateways: old dog now has new tricks in Alzheimer’s neuromodulation. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1389383. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z, Buehler MJ. 2019. Analysis of the vibrational and sound spectrum of over 100,000 protein structures and application in sonification. Extreme Mechanics Letters, 29, 100460. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z, Yu Q, Buehler MJ. 2020. Machine learning model for fast prediction of the natural frequen- cies of protein molecules. RSC Advances, 10, 16607–16615. [CrossRef]

- Roberts AG, Zhang J, Akkus S, Romano D, Kopell BH. 2024. Radiomic Predic- tion of Parkinson’s Disease Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery Motor and Non-motor Out- comes using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping. Preprint available at ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388035895.

- Sadraeian M, Kabakova I, Zhou J, Dayong Jin D. 2022. Virus inactivation by matching the vibrational resonance. Appl. Phys. Rev., 11(2): 021324. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Glinski B, Sharifi K. 2025. Functional Connectivity Changes Following 40 Hz tACS in AD Patients: An fMRI Study. Brain Stimulation. [CrossRef]

- Saporito G. 2024. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) for tremor: short and long-term cognitive outcomes. University of Catania Dissertation Repository. https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/180392.

- Shah BR. 2024. When millimeters matter: Precision in MR-guided focused ultrasound for Parkin- son’s and essential tremor. European Radiology. [CrossRef]

- Soto C. 2003. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci, 4, 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Zou W, Li X, Liang Y, Wang P. 2022. Study and application status of the nonthermal effects of microwaves in chemistry and materials science - a brief review. RSC Advances, 12(27), 17158–17181. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Cui X, Bao L, Liu G, Wang X, Chen C. 2025. A nanoparticle-based wireless deep brain stimulation system that reverses Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Adv., 11, eado4927.

- DOI:10.1126/sciadv.ado4927.

- Zaccai G. 2000. How soft is a protein? A protein dynamics force constant measured by neutron scattering. Science, 288(5471), 1604–1607. [CrossRef]

- Zadorozhnyi R, Gronenborn AM, Polenova T. 2024. Integrative approaches for characterizing protein dynamics: NMR, CryoEM, and computer simulations. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 84, 102736. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).