1. Introduction

The growing interest to equip electric cars with multi-speed gearboxes to increase their efficiency [

1,

2,

3] also leads to novel proposals and solutions in gear shifting itself. The speed of an electric motor can be controlled much easier than the crankshaft speed of a combustion engine, so, the driving motor can directly synchronize the rotation speed of the gearwheel which has to be engaged with the speed of the output shaft. Thus, the use of an additional friction clutch to decouple the motor from the gearbox is not more required, as well as synchronizers inside the gearbox, whose operation principle (synchronization of speeds by friction) inevitably causes their wear and creates related problems [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Instead, a dual-sided dog clutch integrated between two gearwheels can be used [

8]. After the speeds become approximately equalized, the shift sleeve of the clutch, which can move axially on the output shaft, shifts the required gear engaging with the slots of the gearwheel. The preliminary speed synchronization by the driving motor eliminates the main problem of dog clutches, which is a limited range of relative speeds where the gear can be shifted. This can make their application common not only in motorbikes and racing cars [

9] but also in passenger cars [

10].

This fact has made dog clutches an object of many scientific studies in the last years. Researchers from Budapest University of Technology and Economics have intensively investigated the probability of successful shifting at different conditions in early 2010s [

11,

12,

13] and in recent years [

14,

15,

16]. If the face surfaces of the shift sleeve teeth collide with the face surfaces of the teeth on the counterpart during the shifting process, the friction force between them can prevent the further engagement of the teeth with the slots [

11]. To avoid this problem, algorithms for a direct teeth-slots engagement based on the trajectory planning have been proposed by our institute [

17] and also by other researchers [

8,

18,

19]. A related topic of study is reducing the impact force between the side surfaces of the teeth and the slots [

20].

Comparing to the considered problems, the simplification of the clutch actuation has gotten less attention. Usually, the shift sleeve is actuated by a shift fork, which is connected to a rotary motor outside the gearbox via several intermediate parts that transform the rotary motion of the motor to the linear motion of the fork [

3,

7,

8,

9,

16,

18,

19,

20,

21]. A linear actuator has been proposed to avoid the use of intermediate mechanisms, but is still placed outside the gearbox and moves the sleeve indirectly via the shift fork [

22]. To eliminate this drawback, we have proposed a direct actuation of the shift sleeve by electromagnetic actuators integrated into the double-sided dog clutch [

17,

23].

However, it has long been known that the synchronization of the gearwheel and sleeve speeds by the driving motor of an electric or hybrid vehicle just creates another problem, which is called as torque holes [

24]. While the speeds are synchronized, the wheels are disconnected from the motor, significantly reducing the drivability of the vehicle. The solutions proposed earlier [

25] and recently [

26,

27] always include the use of two electric motors, one of which is connected with the wheels and propels the vehicle while the other synchronizes the rotation speeds in the gearbox. The torque holes can be minimized with the use of only one motor if a dual-clutch transmission is applied [

28]. Basically, it is a manual gearbox with two countershafts, where one of them drives the gearwheels of even gears (1, 3...) while the second drives the gearwheels of odd gears (2, 4...), and two multi-plate clutches connected with the corresponding countershaft. Switching between the countershafts is realized by releasing one clutch and connecting the other to the driving motor. All gearwheels can freely rotate on the output shaft or be coupled with it mechanically by corresponding shift sleeves. The required odd gear can be pre-selected and shifted by engaging the corresponding gearwheel interlocked with the disconnected countershaft while the vehicle is being propelled in an even gear (or vice versa). However, synchronizers are required again to equalize the rotation speed of the pre-selected gearwheel with the output shaft speed. If the shifting actuator could apply torque on the gearwheel to increase or reduce its rotation speed before the shift sleeve is axially moved under the influence of the force generated by the actuator, the synchronizers would no more be necessary. Such an actuator can find application not only in dual-clutch transmissions but also replace synchronizers in manual transmissions and automated manual transmissions [

29] to avoid a possible failure caused by wear [

30].

To generate not only axial shifting force bur also synchronizing torque, a linear-rotary actuator is required. Linear-rotary electromagnetic actuators (LREAs) presented in the literature are either complex structures with numerous permanent magnets (PMs) [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] or common electrical machines with multiple stator packets [

38,

39]. They are not suitable for the use as a shifting actuator integrated into a dog clutch due to their size and complexity. Therefore, a novel LREA for application in dog clutches was firstly proposed by B. Miroschnitschenko in [

40]. The method of design and optimization is developed for the LREA in [

41], and modified designs with additional features are described in [

42]. It has a very simple construction, where no PMs are required, and only two coils are placed coaxially. The shift sleeve of a one-sided dog clutch and its counterpart represent active parts of the actuator. Thus, it can be simply integrated and applied to synchronize the speeds of two rotating elements and de-/couple them mechanically.

The design and operation principle of the LREA presented in [

40,

41] are briefly introduced in Section II. To allow the use of the actuator as a double-sided dog clutch, its topology can be simply repeated on the side of the second gearwheel. However, this will double its size and number of parts. To avoid this, we propose a modified design of the actuator, that represents a double-sided electromagnetically actuated dog clutch, in Section III. Its operation principle is similar to the operation principle of the one-sided clutch and is also described in Section III. However, the control algorithm for the synchronization of rotation speeds is more complex. It is developed in Section IV. Moreover, a control algorithm for a direct teeth-slots engagement to eliminate the possibility of unsuccessful shifting is given in Section IV together with the mechanics of the shifting process and simulation results. The basic idea and theoretical results of this and previous works are experimentally verified in Section V, which also describes the developed testrig with a prototype of the double-sided clutch placed into a designed testing gearbox. The conclusions are drawn in Section VI.

2. Design and Operation Principle of a Novel One-Sided Dog Clutch

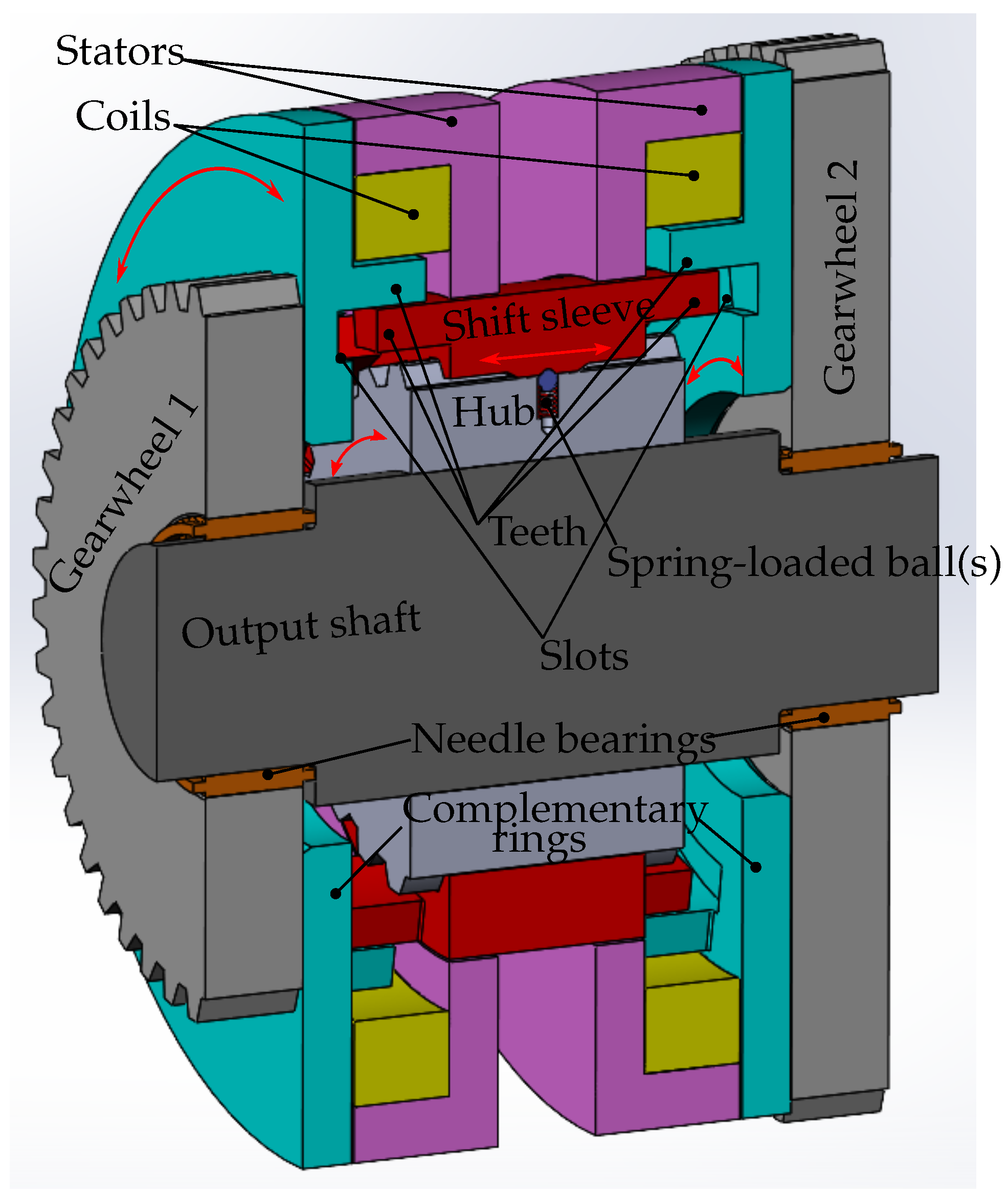

The LREA (

Figure 1) which represents a one-sided dog clutch has been proposed in [

40]. Below, it is briefly introduced. For a better understanding, the reader is referred to [

40,

41,

42]. The actuator has two coils mounted on the stators, the shift sleeve and the complementary ring which is located opposite to the shift sleeve. The sleeve, the ring and the stators are made of soft magnetic steel and placed coaxially relative to each other. The complementary ring is rigidly connected to shaft 1, and the shift sleeve is mounted axially moveable on shaft 2. It is worth mentioning that other rotating elements can be used instead of the shafts, for example, one shaft can be replaced by a gearwheel. The shift sleeve and the complementary ring have the teeth and slots placed on their inner side surfaces. The number of teeth

z is same on each element, as well as the number of slots and teeth on one element. Moreover, all teeth have the same angular length

, and all slots have the same angular length

, and

is slightly larger than

. Finally, the teeth and the slots are placed angularly equidistant forming the pitch between the teeth (and the slots)

, which is equal to 360/

z degrees.

If the left coil is excited, its current creates the magnetic flux

that closes via the left stator, the shift sleeve and the ring, and reluctance forces arise under the influence of

. The axial component of the reluctance force

created by

works on the shift sleeve and can move it axially towards the complementary ring. If the right coil is excited simultaneously, the magnetic flux

, that closes via the right stator and the shift sleeve, arises creating an axial reluctance force

with the opposite direction. As long as

is greater than

, the sleeve remains at its initial axial position where the radial air gap between the teeth is much smaller than the axial distance between the sleeve and the ring. In this case, the permeance of the magnetic circuit is maximal at the position where the teeth are completely radially aligned. This position correspond to the relative angle between the ring and the sleeve

. Thus, if the relative angles between a tooth of the sleeve and the nearest two teeth of the ring are not equal, reluctance torques which work on the shafts arise. These torques tend to rotate the shafts towards each other and align the nearest teeth radially, i.e., to make the relative angle equal to zero. The axial movement of the shift sleeve can engage the teeth of one element with the slots of the opposite element in the range of the relative angular positions between

and

, where

is the angular backlash:

The sleeve can be easily moved and engaged by deexciting the right coil making

uncompensated. If engaged, the teeth and the slots interlock and couple the shafts mechanically. To decouple the shafts, the left coil can be deexcited while the right coil is excited again creating

that moves the sleeve back towards the right stator disengaging the teeth.

If the shafts are rotating with different speeds, the speed difference

leads to the change of

in the range between

and

. The values between

and 0 correspond to the positions where the nearest teeth of the complementary ring are located relative to the sleeve teeth in counterclockwise direction, and the values between 0 and

to the positions where the nearest teeth of the complementary ring are located relative to the sleeve teeth in clockwise direction. If the left coil is excited during the relative rotation, reluctance torques with the same absolute value

but opposite signs work on the sleeve and on the ring. Zero torques are generated at the relative angles

and

, moreover, the torques change their signs at these positions. Considering the clockwise direction as positive direction for torques, positive torque works on the complementary ring in the range of negative

, and negative torque works on the ring in the range of positive

. Basically, the actuator is similar to a homopolar single-phase switched reluctance motor [

43]. By exciting and deexciting the left coil in the appropriate range of

, reluctance torques with the desired signs can be generated to synchronize the rotation speeds. The arising

can be compensated by exciting the right coil, as it was described above. As soon as the rotation speeds are almost synchronized, the residual speed difference can be used to bring

into the range where the teeth can be engaged with the slots directly avoiding the contact between the teeth and the side surface of the opposite element. This state is also called as the face contact phase and can lead to unsuccessful shifting [

11,

12,

13]. After that, the right coil is deexcited, and the shift sleeve moves axially towards the complementary ring. Thus, a smooth engagement is achieved, and impacts caused by significant speed difference as well as the face contact phase are avoided.

The one-sided actuator can be used for smooth mechanical coupling of two rotating shafts and can find its application, for example, to turn on and turn off a 4-wheel drive in automotive area. However, automotive gearboxes regularly require double-sided dog clutches which can switch between three shifting states, i.e., disengaged (neutral), gear 1 engaged and gear 2 engaged. In this work, we present a modified LREA with an extended functionality suitable for operation as a double-sided dog clutch.

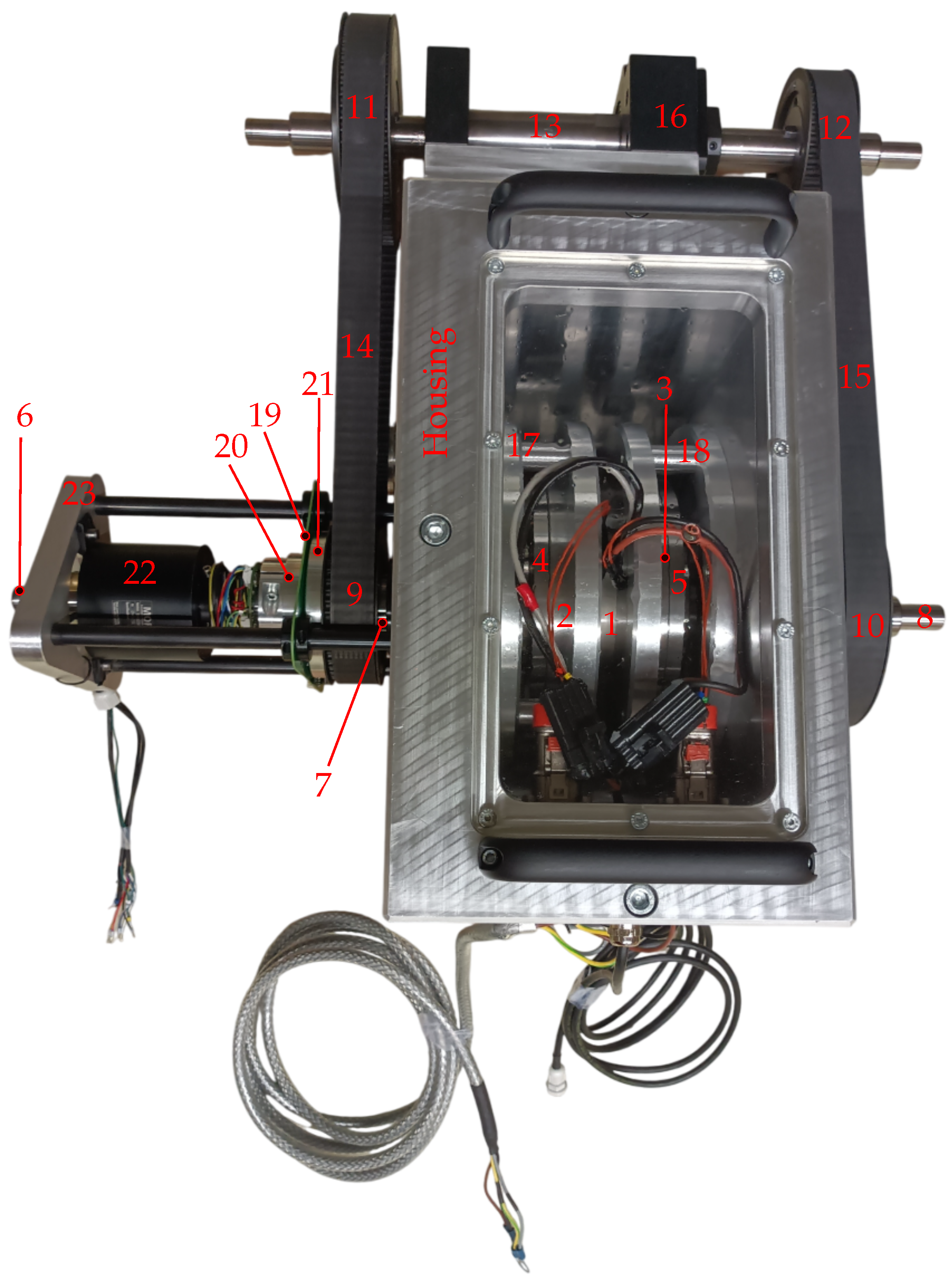

3. Design and Operation Principle of a Novel Double-Sided Dog Clutch

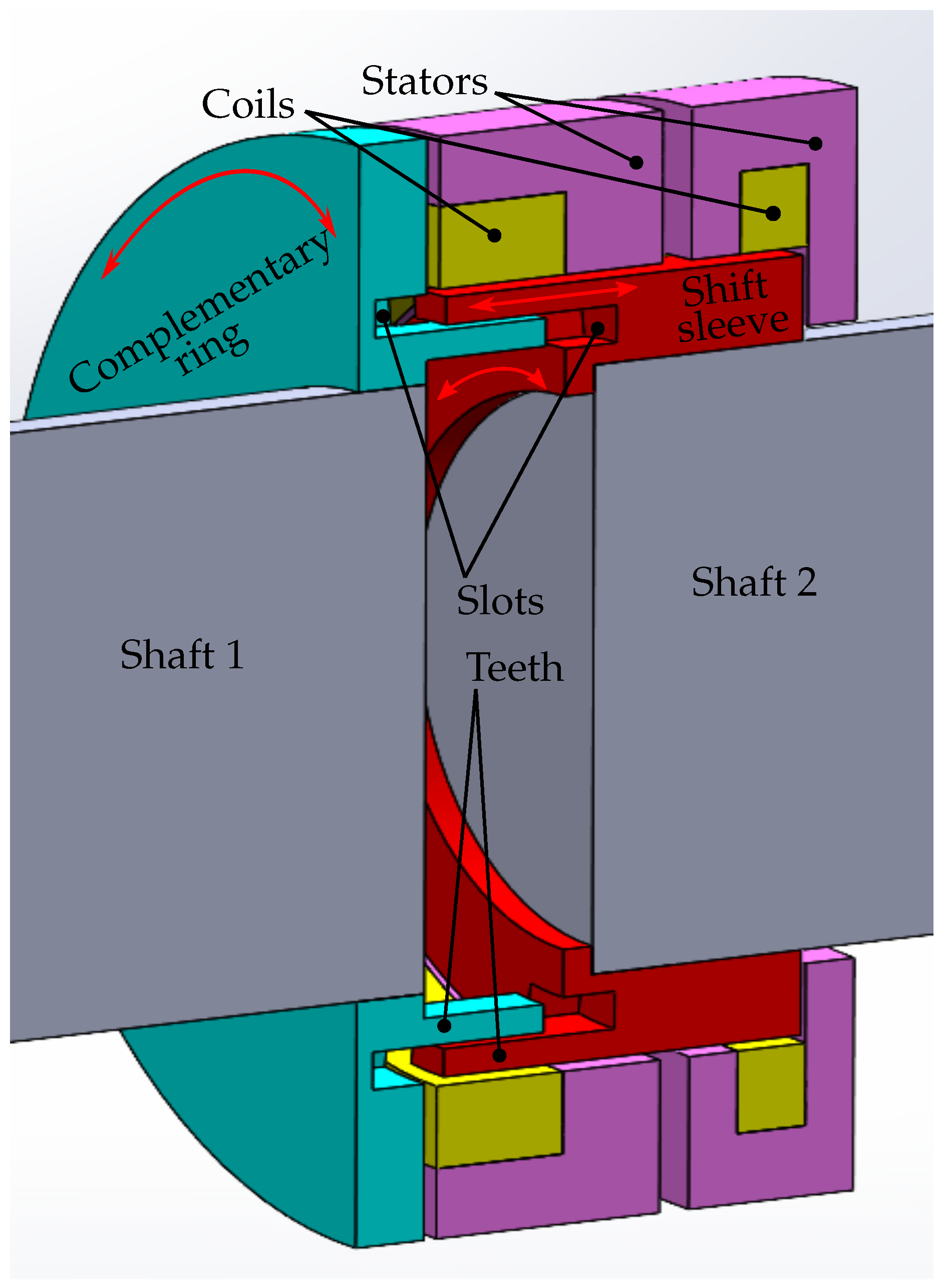

The design of the double-sided dog clutch (

Figure 2) is similar to that of the one-sided clutch. The stators, the coils and the complementary rings are placed on each side. The dimensions of the parts on the left side are equal to the dimensions of the corresponding parts on the right side. The complementary rings are rigidly connected to the gearwheels of a gearbox, and the shift sleeve has teeth on both side surfaces and is placed axially movable on the splines of the hub, which is fixed on the output shaft. The shift sleeve is made without slots to reduce its radial size and mass. Since there are no slots in the shift sleeve, the ring teeth, which are placed above the sleeve teeth in radial direction, always remain unengaged. There are 9 tooth pairs on each side, so

ranges between −20° and 20°. The sleeve teeth can be engaged with the ring slots by axial movement of the shift sleeve, same as in the one-sided clutch. The angular length of the teeth

and of the slots

are 18° and 24°, respectively, making the angular backlash

equal to ± 3°. The needle bearings are placed between the gearwheels and the output shaft, so that the gearwheels can rotate on the shaft.

The gearwheel teeth are interlocked with the teeth of the countershaft (the countershaft is not shown in

Figure 2). Thus, together with the countershaft the gearwheels form two gears with the different gear ratios

on the left side and

on the right side. If the shift sleeve is disengaged and the countershaft rotates, the gearwheels rotate with the different speeds

and

, which are related with the countershaft speed

as

Consequently,

and

relate to each other as

and the relative rotation speeds

,

with different values are presented on the sides:

where

is the rotation speed of the shift sleeve, which is equal to the rotation speed of the output shaft.

The axial reluctance force and the reluctance torque can be generated on each side with the same principle as in the one-sided clutch. If the sleeve remains at the central axial position

x = 0, the magnetic circuits on the sides are symmetrical and the sides are magnetically decoupled, so that the electromagnetic torque

and the axial electromagnetic force

, which act on the gearwheel and on the shift sleeve, respectively, can be described for

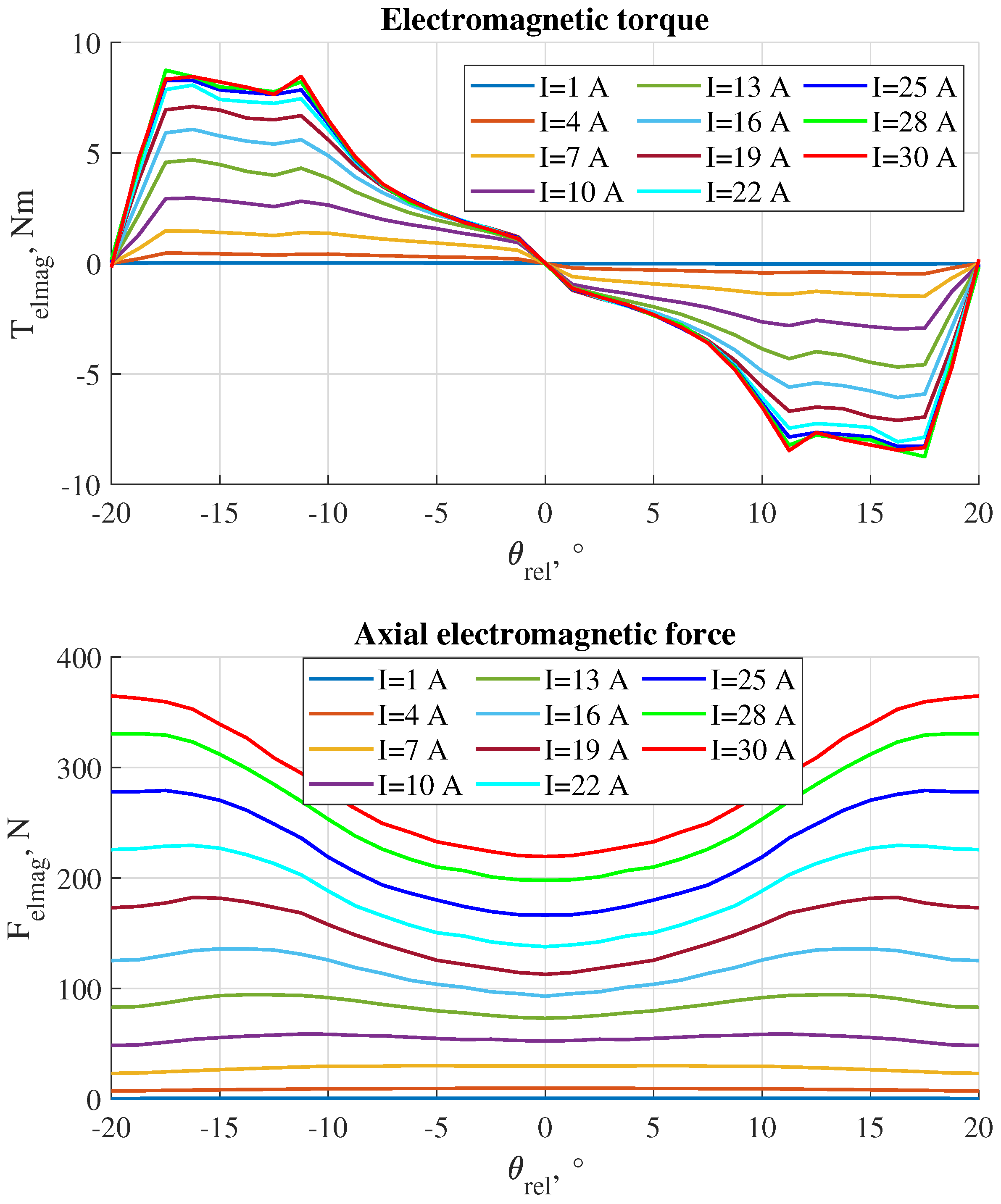

x = 0 with the same torque and force characteristics shown in

Figure 3 for both the left and right sides. There,

is the relative angular position between the shift sleeve and the complementary ring of the considered side, and

I is the current of the corresponding coil. A required gear can be shifted by exciting the coil on the corresponding side creating

that overcomes the holding force of the spring-loaded balls

and moves the shift sleeve towards the gearwheel engaging the teeth with the slots of the complementary ring. When engaged, the sleeve and the gearwheel rotates together, so that the output shaft and the countershaft are coupled mechanically. Assuming that the countershaft is connected to the driving motor, the motor torque can be transmitted to the output shaft, so that the output shaft can be rotated with a higher speed or a higher torque depending on the gear ratio of the shifted gear.

The gear can be disengaged by exciting the coil on the opposite side. If the created axial reluctance force is lower than and the motion speed is relative low when the shift sleeve reaches the central position, the sleeve can be stopped at x = 0, so that the clutch is set in neutral gear position again. Otherwise, the sleeve overcomes the central position and engages the opposite gearwheel, so that the other gear is shifted. Consequently, an active force control is required to put the clutch back in neutral positions. The easiest way to do this is to place a sensor that will measure the axial position of the shift sleeve, so that the coil currents on both sides are controlled depending on the measured position to stop the motion at x = 0. However, the position sensor will increase the complexity and the manufacturing costs of the clutch. Moreover, the sensor must be placed inside the gearbox in the aggressive environment of transmission oil mixed with metal particles, which inevitably arise due to the wear of the parts. This might significantly reduce the clutch reliability. A preferred alternative is the development of a sensorless control method that allows to control the motion of the shift sleeve without a direct measurement of its axial position. This method will be presented in the following publication.

The main difference of the operation principle of the double-sided clutch comparing to that of the one-sided clutch is the method of speed synchronization. The axial force that arises on the side which generates synchronizing torque can not be compensated by simply exciting the coil on the opposite side, as it can be done in the one-sided clutch [

41]. It changes with the change of

, and the force difference rises with the increase of the coil current (

Figure 3). Since the relative rotation speeds

,

are different, the relative angular positions on the left

and the right

sides change asynchronously. Thus, the coil currents must be controlled differently to keep the force balance. If the difference between the forces exceeds the holding force created by the spring-loaded balls

, the shift sleeve starts to move axially. If the force disbalance is not eliminated quickly, the shift sleeve leaves the neutral gear position and move to the side with the higher force, which will lead to the collision between the sleeve and the corresponding complementary ring. This collision is especially dangerous at high relative speeds and may cause damage to the clutch. Moreover, not only an axial force but also torque will be generated by exciting the opposite coil. The direction of this torque can be positive and negative depending on the relative position on the side. This can result in a situation where the side which is used to balance the axial force increases the rotation speed difference stronger than the side used to generate the synchronizing torque decreases it. Therefore, a special control algorithm for speed synchronization is developed in the next section.

4. Algorithm for Gear Shifting with a Preliminary Speed Synchronization in a Gearbox Equipped with the Double-Sided Clutch

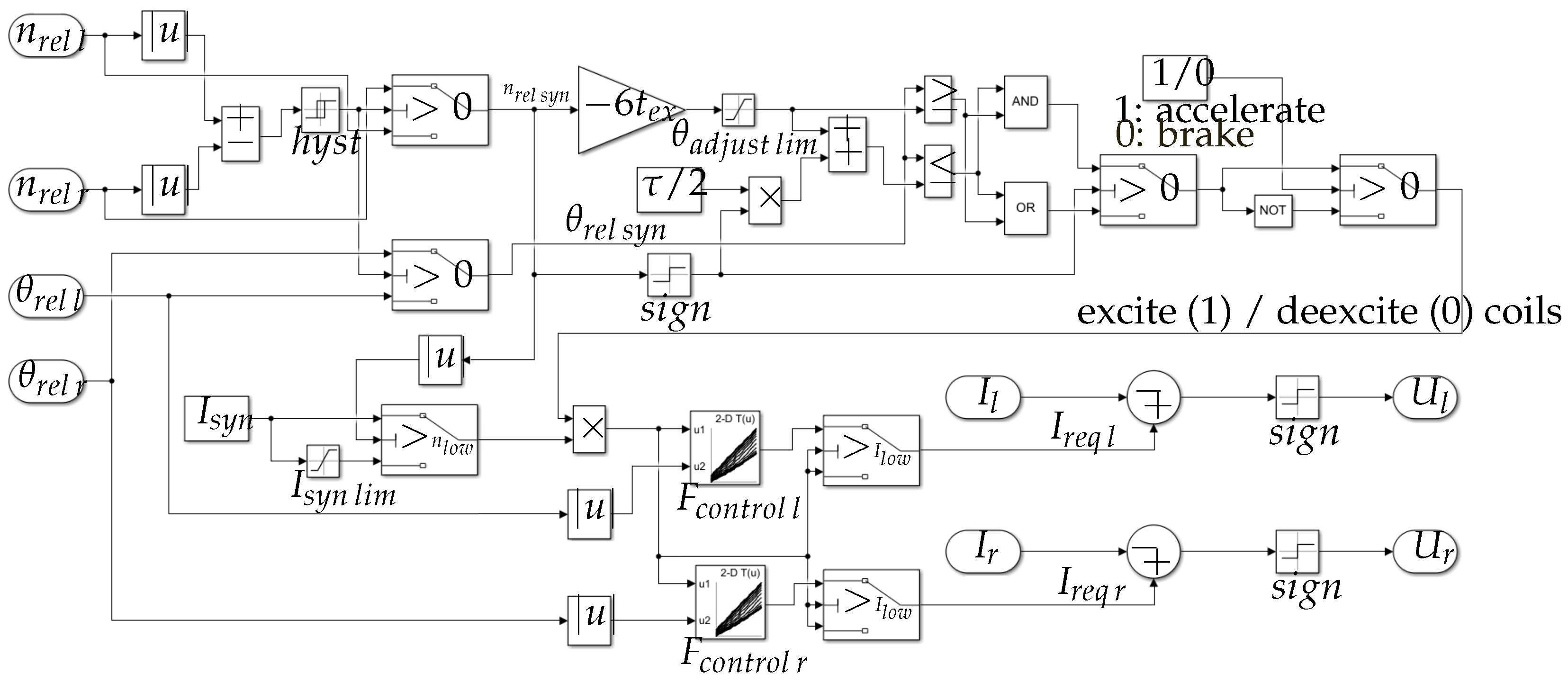

To synchronize the rotation speed of the gearwheel, which has to be engaged, with the rotation speed of the shift sleeve, positive or negative torque must be generated by the actuator depending on the sign of the relative speed. For this purpose, one actuator side is used for torque generation while the other compensates the arisen axial force. For further considerations, we name these sides as synchronizing and compensating side, respectively. The synchronizing side produces the torque with the desired direction

and besides of that an undesired axial force. The compensating side is excited and de-excited simultaneously to balance the axial force and also generates the collateral torque

. We can assume that the absolute value of the relative speed on the synchronizing side

is higher than that of the relative speed on the compensating side

. In this case, the relative angular position on the synchronizing side

changes faster than the relative angular position on the compensating side. Since

changes with

(

Figure 3), this will inevitably lead to the situations when the absolute value of the average torque generated on the compensating side during one excitation period is higher than the absolute value of the average torque generated on the synchronizing side during that period. If the torque signs are different, the speed difference will be increased instead of being reduced. Therefore, the side with the lower

must be chosen for torque generation, while the opposite side with the higher

is used to compensate the axial force. In this case,

has different signs during one excitation period, so that its average absolute value declines with the increasing difference between

and

. Over a longer time period, the integral of

becomes approximately equal to zero. If the synchronization starts when

is much higher than

, the influence of the compensating side on the synchronization process is negligible. To avoid frequent switching between the sides when

and

are almost equal, a hysteresis band can be added to the comparator of the relative speeds.

The coil on the synchronizing side must be excited in the negative range of

to generate a positive torque, while a negative torque is generated in the range of positive

(

Figure 3). At positive

,

changes from −20° to 20° during one period, and at negative

it changes from 20° to −20°. Thus, to create positive

while

0, the turn-on relative angle for the coil on the synchronizing side

is 0°, and the turn-off relative angle

is −20°. For

0 and required

0,

and

become equal to −20° and 0°, respectively. To generate negative torque, the turn-on and turn-off relative positions are simply inverted, i.e.,

becomes

, and vice versa. However, the given values of the turn-on and turn-off angles assume the ideal case when the coil can be excited and de-excited instantly. In fact, the coil inductance makes an instant current change impossible, thus,

and

must be adjusted depending on the relative speed on the synchronized side, the inductance and resistance of the coil and supply voltage, therefore, considering all these influences, the adjustment angle

is introduced.

When the coil is being excited, its current

I rises according to the following equation:

where

U is the applied voltage,

R is the coil resistance,

L is the coil inductance,

e is Euler’s number and

t is the time elapsed after the start of excitation. Consequently, the time

required to excite the coil on the synchronizing side changing its current from

I = 0 to the required value

can be calculated as

The time required to demagnetize the coil changing its current from

to

I = 0 is approximately equal to

. Finally, the adjustment angle

is calculated as

where 6 is the scaling factor from rpm to degrees per second. The coil on the synchronized side is turned on and turned off

degrees earlier comparing to the idealized

and

. For example, if the calculated

is 5°,

0 and positive torque is required,

is 5° and

is −15°. For

0 and positive required torque,

and

become −5° and 15°, respectively. Since

is directly proportional to

, it reaches the value

at some

, so that the actuator will generate only an undesired torque. To avoid this situation,

is limited with the value

.

We note that the coil inductance

L changes with its current and relative position on the side, and

R changes with the coil temperature. So,

becomes lower if the coil temperature rises, or if the coil is turned on or turned off at the unaligned position. To simplify the calculation,

L can be assumed equal to the coil inductance at the unaligned position and average actuator current, and

R can be assumed equal to the coil resistance at 20°C. In the considered actuator, these values are 22 mH and 0.75 Ohm, respectively. This simplification causes some delayed de-/excitation on the synchronizing side when

is close to the aligned position

. However, the amplitude of torque generated around the aligned position is low (

Figure 3), so that this delay is insignificant. The eddy currents in the steel also delay the de-/magnetization and reduce the generated torque. However, the most important role plays the supply voltage, which value

U is directly proportional to the speed of current rise/fall (Equation (

7)). So, if

U is not high enough, the coil current can not reach the required value

at higher

, and the synchronizing torque

decreases significantly. Thus, an efficient synchronization is possible in a limited range of

.

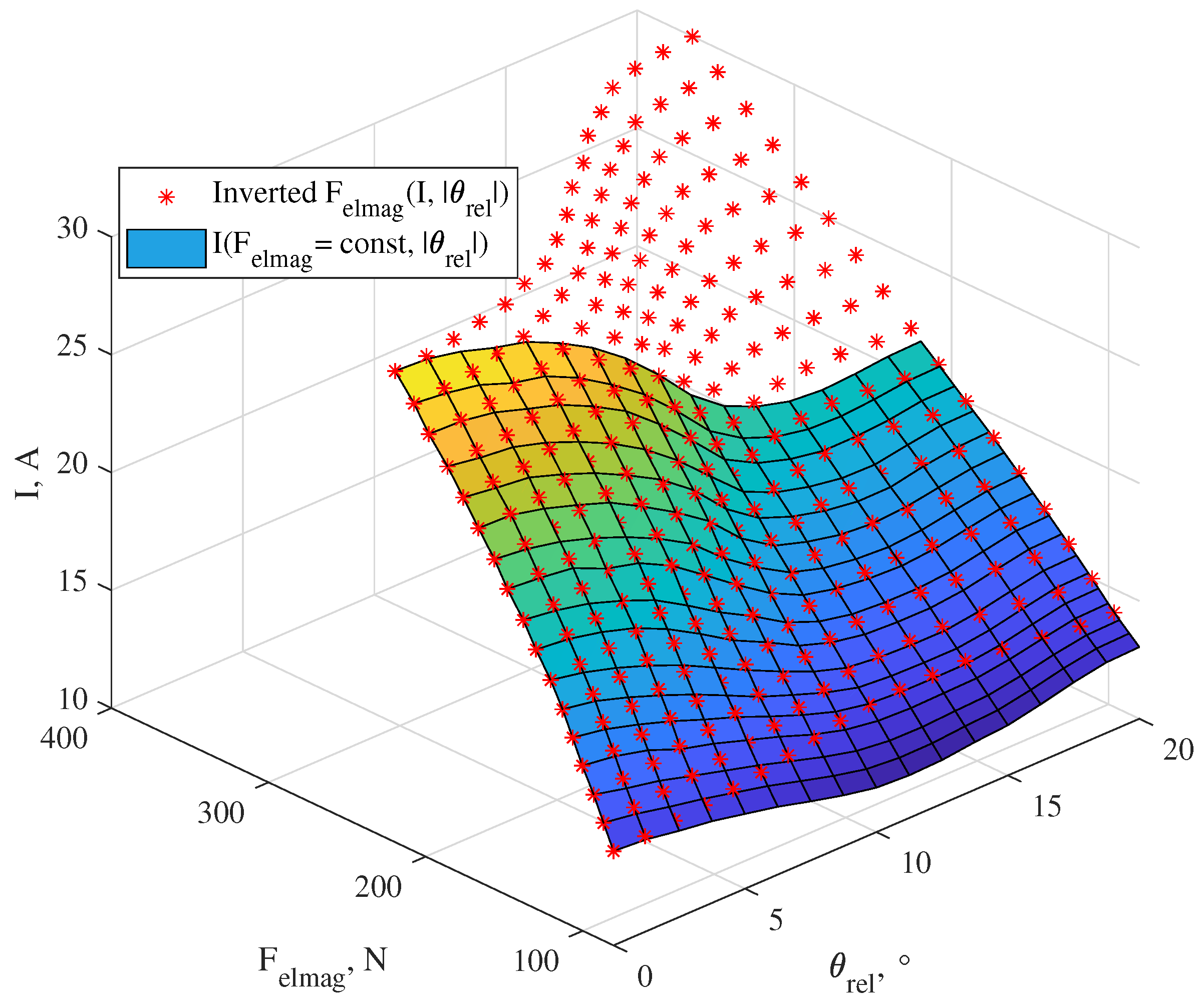

To achieve the balance of the axial forces, we propose an algorithm based on the inverted force characteristic (

Figure 4). There, the initial force characteristic

for

(

Figure 3) obtained from a 3D finite element model of the actuator is inverted to the form

. Since the axial force is the same for

and

, the absolute value

is enough. Interpolating the inverted characteristic using a radial basis function [

44], the current values at which the force remains equal to

were found for different values of

and

(

Figure 4). Now, adjusting the coil currents depending on the required value of the synchronizing current

and the measured value of

on the corresponding side, approximately equal axial forces can be created on both sides. However, it is not feasible to create a full force balance due to the influence of different uncertainties (eddy currents, deviations caused by manufacturing tolerances, difference between the simulated model and the real actuator, etc.) The residual force difference can be defined as

. The axial position of the shift sleeve during the synchronization of the rotation speed is described by the equation

where

m is the mass of the shift sleeve. In the area of the central position,

is directed to keep

, i.e., is opposite to

. Thus, a low residual electromagnetic force can be compensated by the spring-loaded balls.

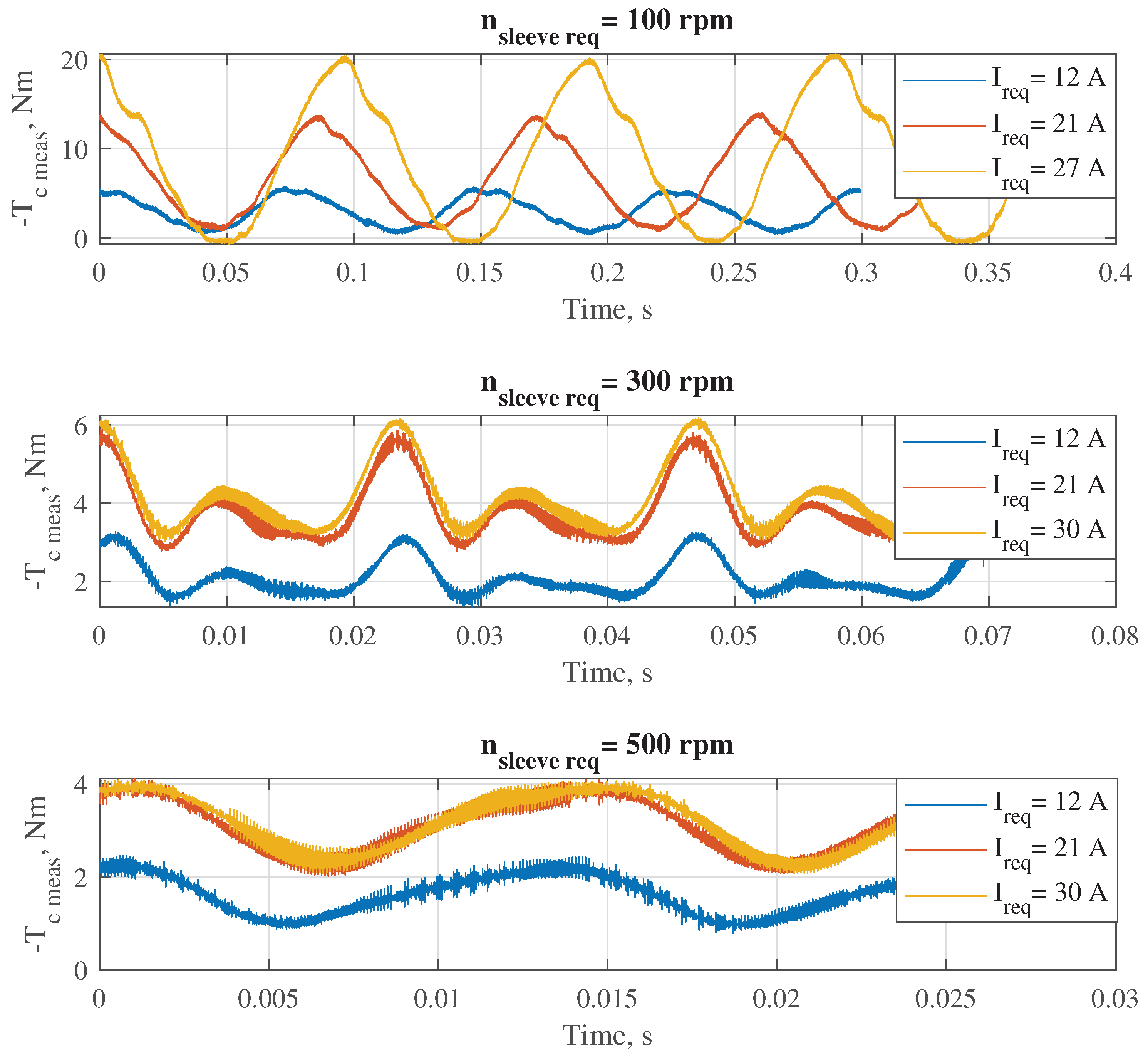

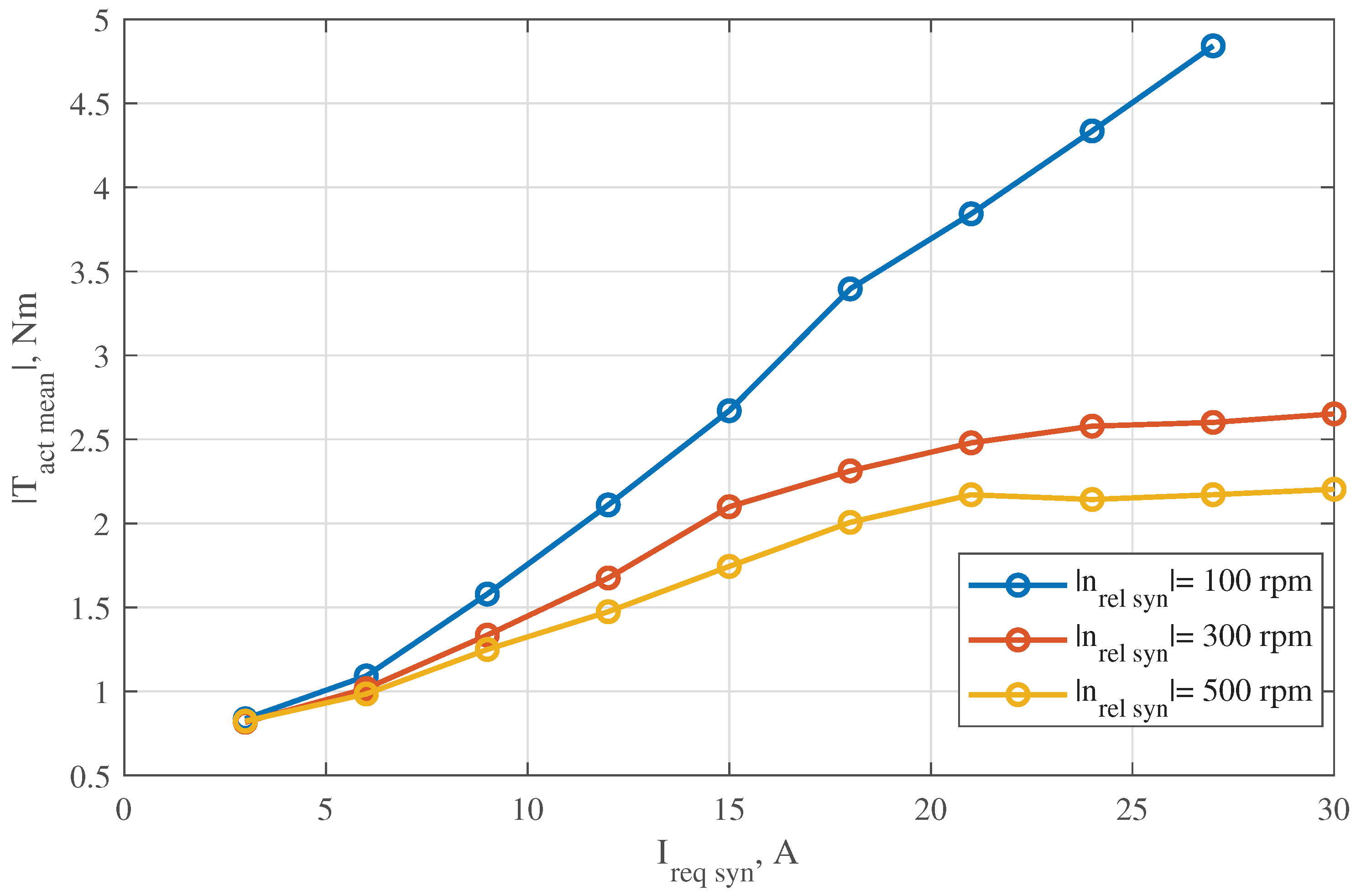

As it is shown in

Figure 3, the change in

is small in the area of lower currents. There, an active adjustment of the side currents is not required, since the residual force difference can be balanced solely by the spring-loaded balls. In the proposed actuator, the current adjustment on both sides is not required if

is less than

= 14 A. On the contrary, the uncertainties increase

at higher currents, and it acts longer on the shift sleeve at lower relative speeds since the time period of coil excitation rises. As it follows from (

10), the shift sleeve will move a longer distance from the central position causing the further rise of

since the axial air gaps between the sleeve and the complementary rings of the sides become different. This will lead to the case when the axial forces can not be balanced any more. To avoid this problem, the required synchronizing current

must be limited at

less than the value

. The limitation is relatively small and can be chosen equal to 27 A in the proposed actuator, which is designed for the maximum operating current 30 A, while

is chosen equal to 100 rpm. Finally, the coil voltages are controlled based on the difference between the required and measured currents using hard chopping method common for rotary reluctance machines [

45]. The entire control algorithm for the synchronization of the rotation speeds is shown in

Figure 5.

Further, we shortly describe the mechanics of the shifting process. The resulting torques which work on the left

and right

gearwheels and on the shift sleeve

can be calculated as

where

,

are the electromagnetic torques generated by the actuator on the corresponding side,

,

are the friction torques on the corresponding gearwheel,

is the friction torque on the countershaft and

is the load torque on the output shaft. The total values of the moment of inertia on the gearwheels

,

are

where

,

and

are the moments of inertia of the left gearwheel, right gearwheel and of the countershaft, respectively. The moment of inertia on the shift sleeve

is equal to the moment of inertia on the output shaft. The change of the angular velocities during the synchronization is then calculated from the equation of angular motion

where

,

,

T and

J are the angular velocity, the initial angular velocity at the start of the synchronization, the resulting torque and the total moment of inertia of the corresponding part, respectively. If the rotation speed of the gearwheel which has to be shifted is higher than

, the gearwheel can always be synchronized with the sleeve. However, if

0, the actuator must be able to generate enough torque to overcome the resulting friction torque of the gearwheel. As it follows from (

11,

12), it is always harder to accelerate the bigger gearwheel.

The relative speed on the side which has to be shifted is synchronized to some small residual value

0, which is used to reach the relative position where the teeth can be directly engaged with the slots. This position can be named as

and calculated based on the obtained

and the time required to move the shift sleeve from the central position to the engaged position

[

17]:

The angular backlash (Equation (

1)) allows an error in the calculation of

if the absolute value of the error is less than

.

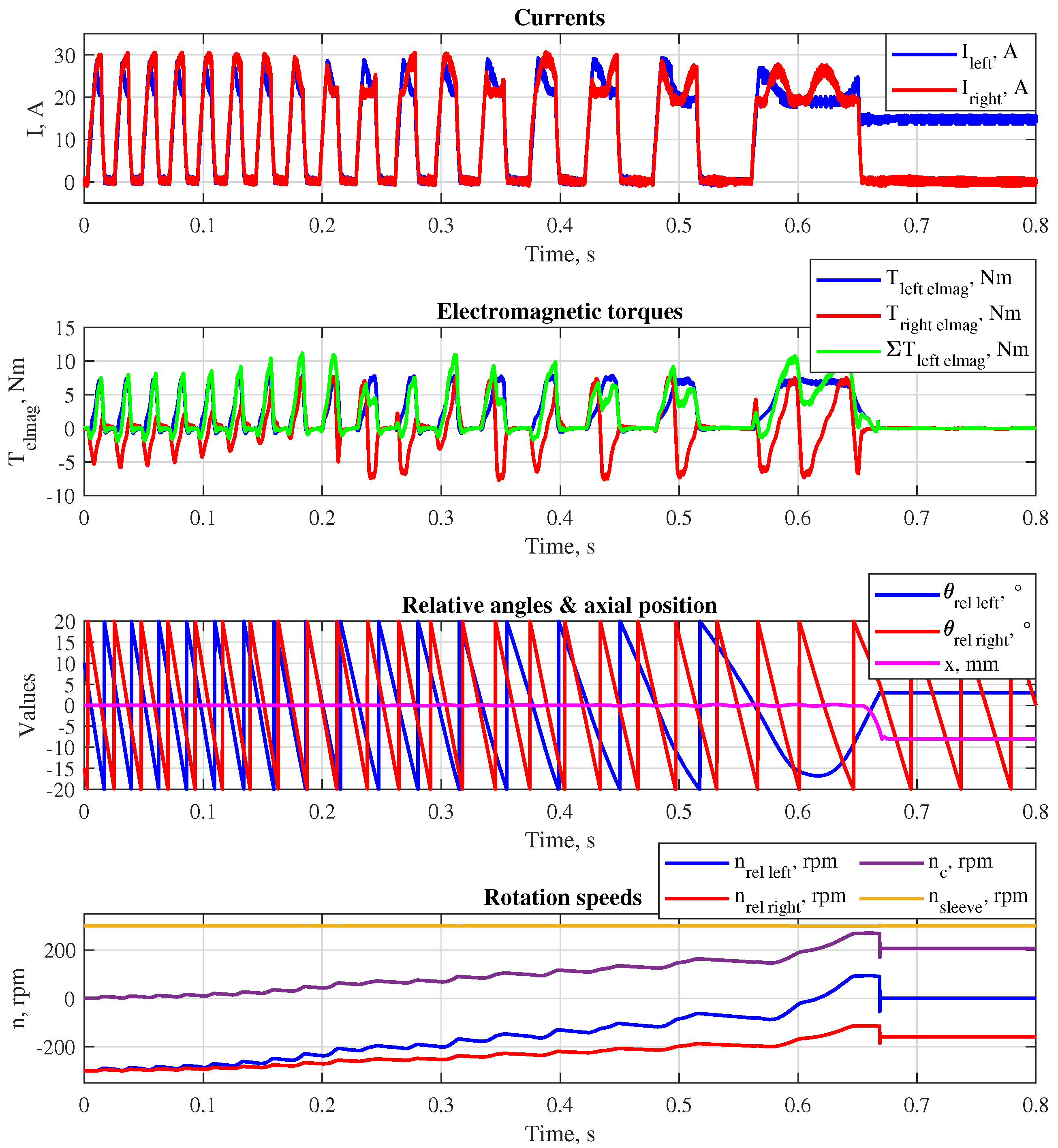

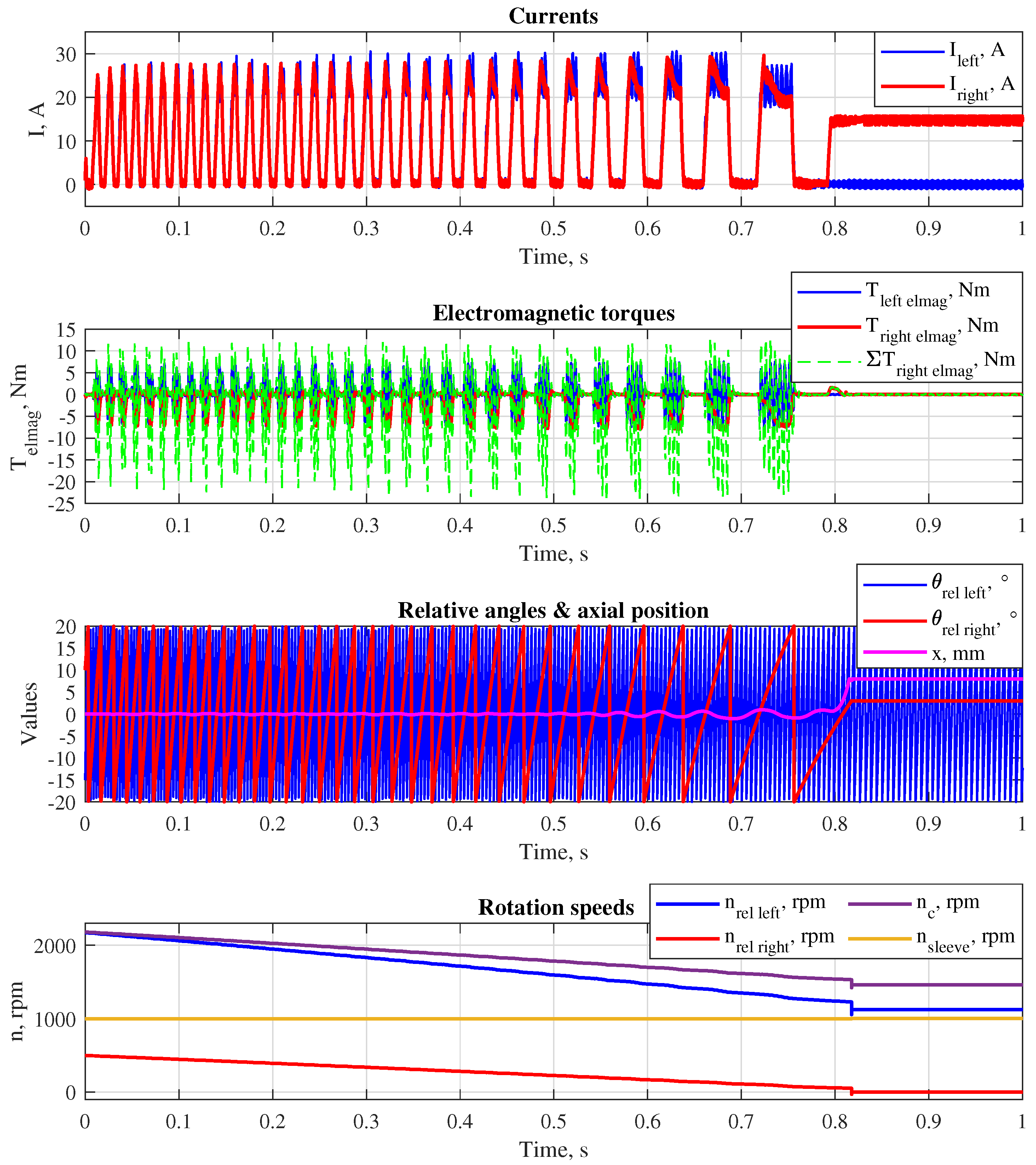

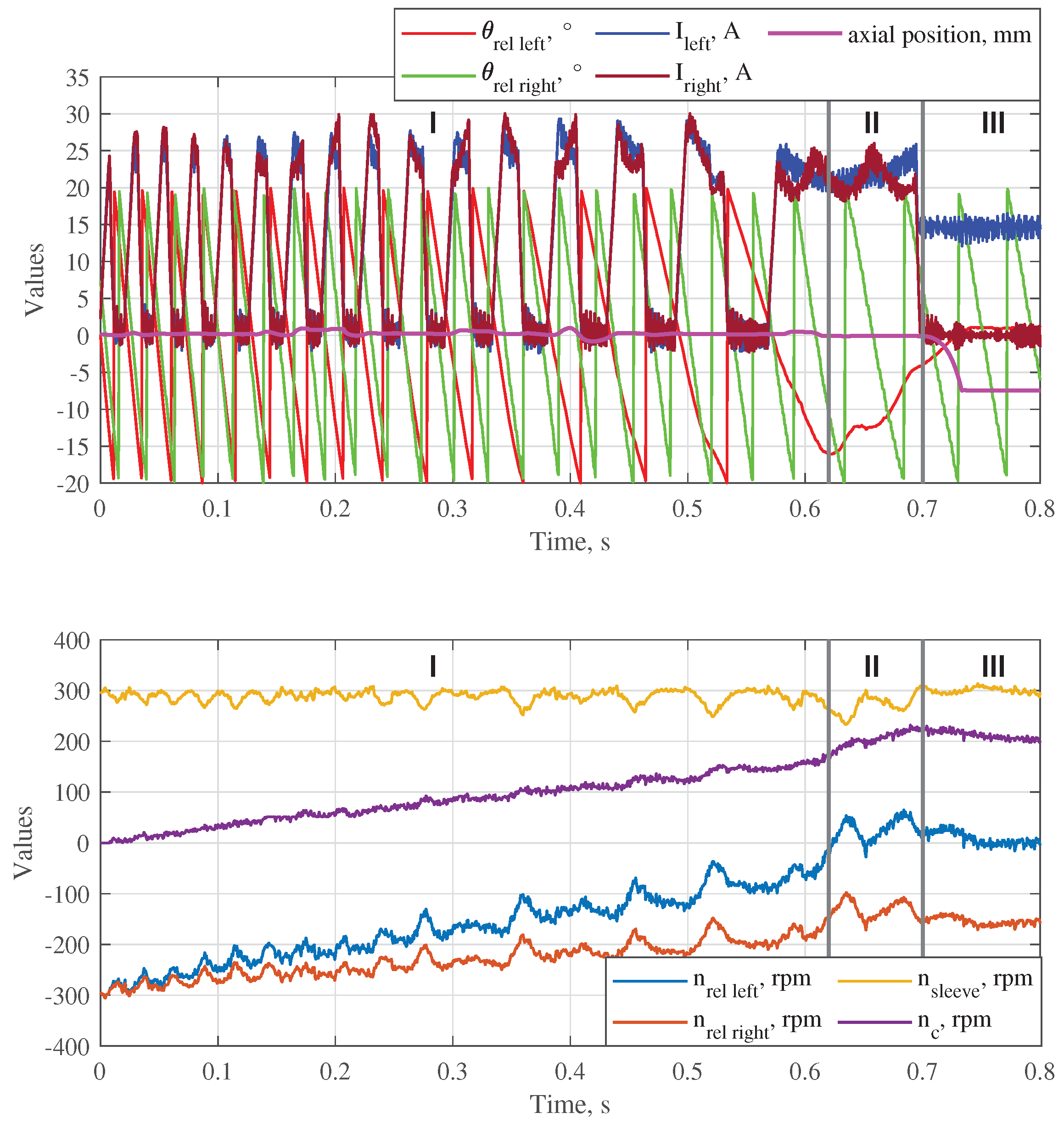

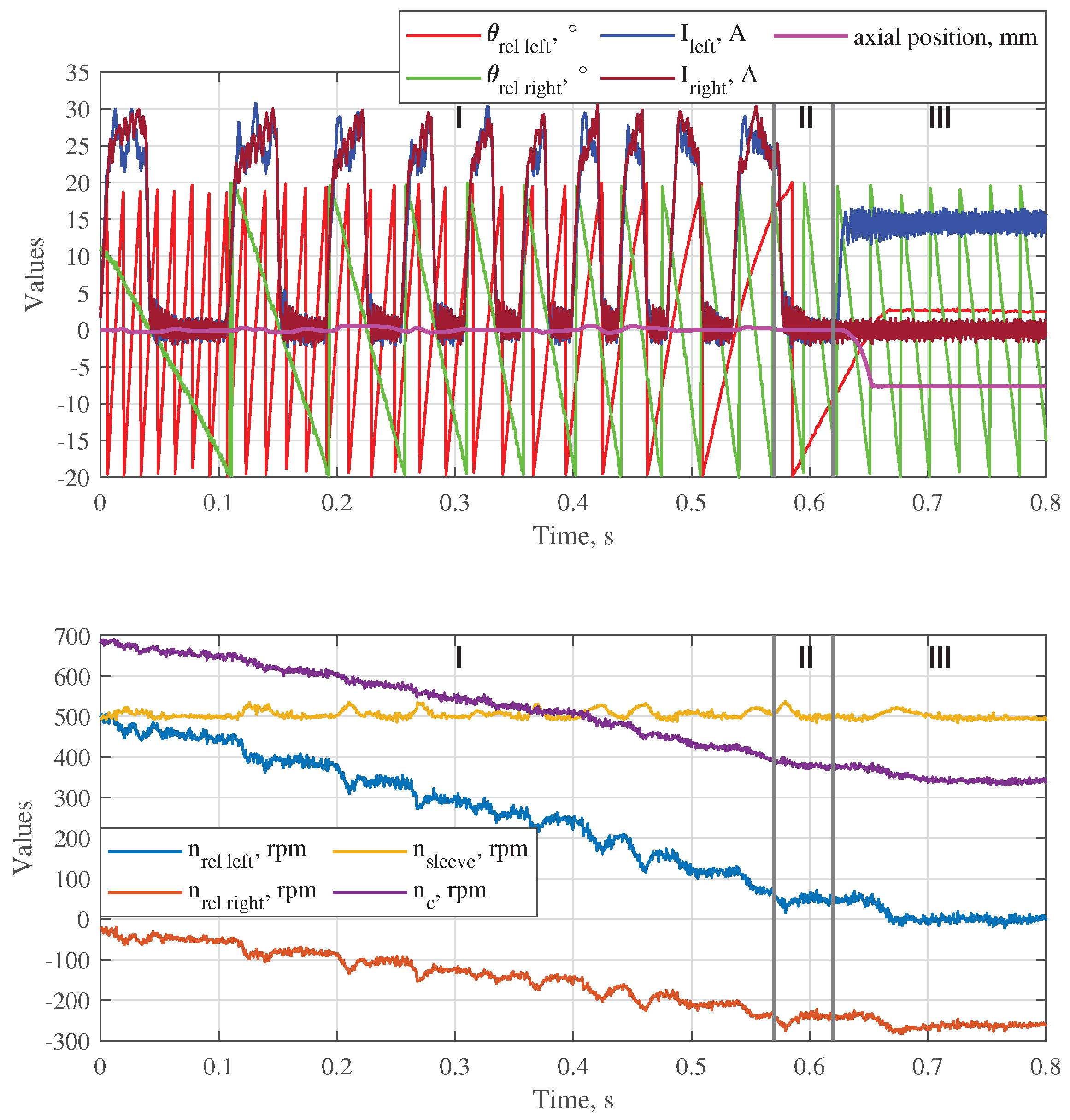

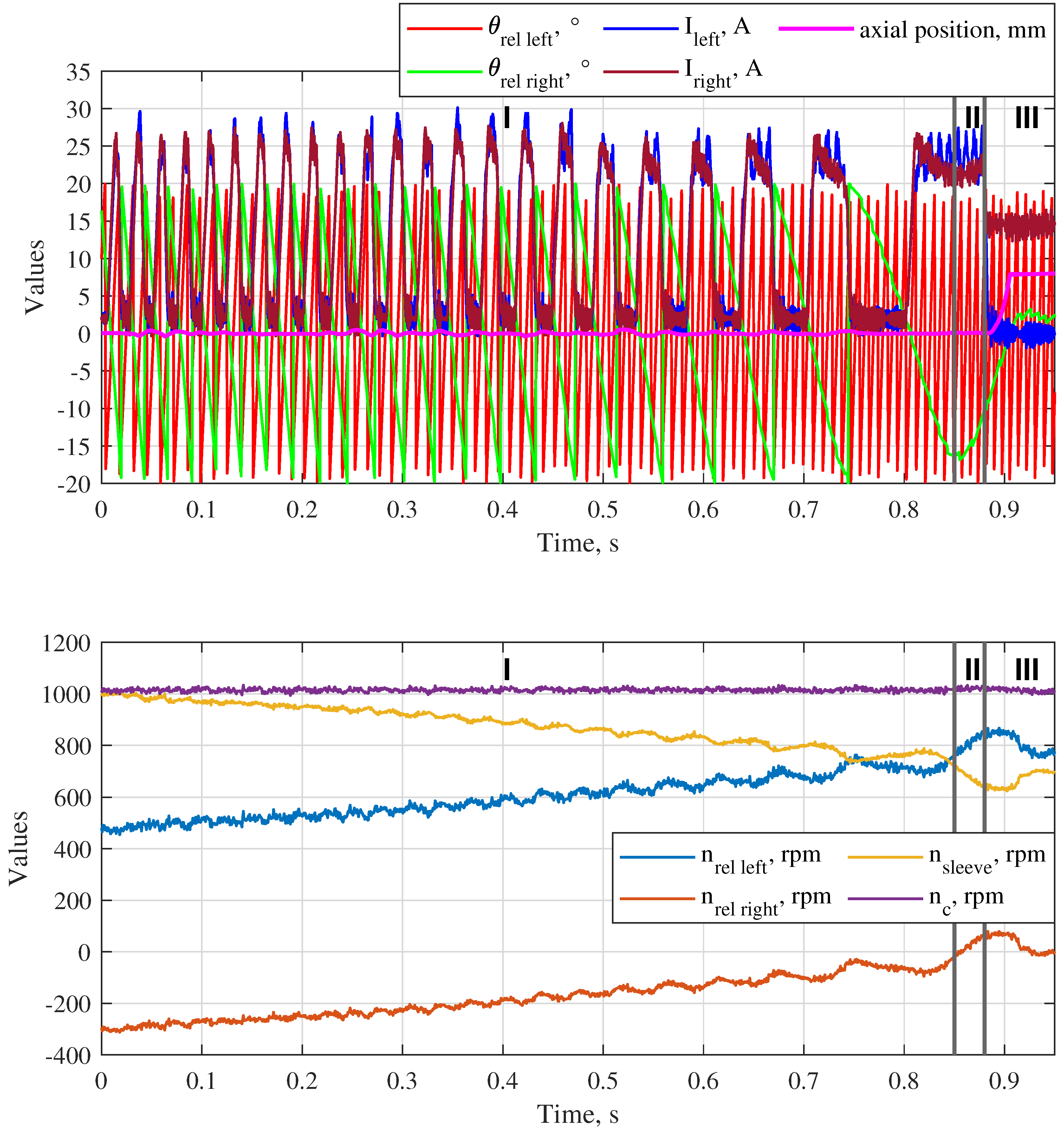

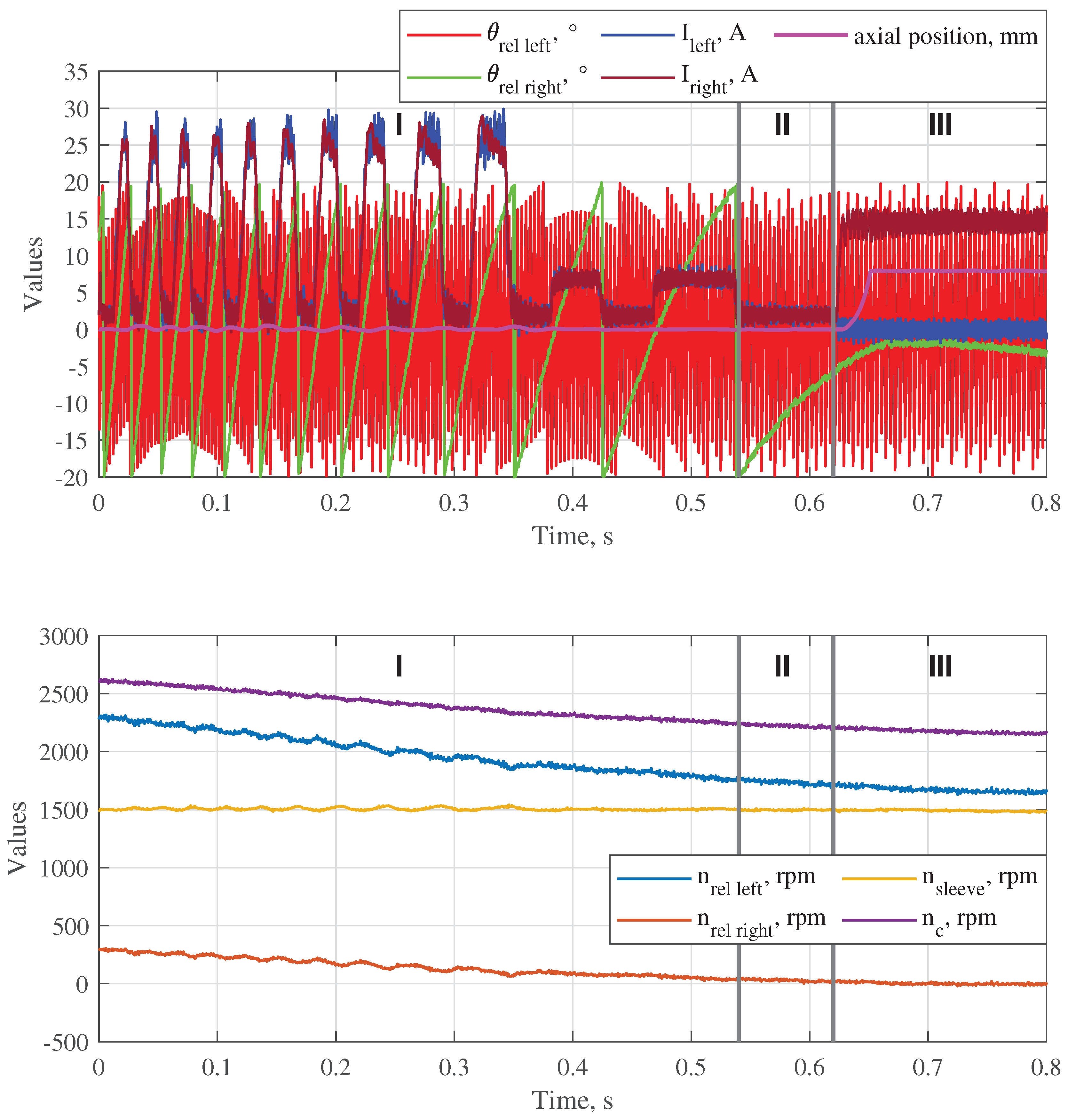

To show the entire shifting process, two different situations were simulated for a gearbox with the reciprocal gear ratios

= 44/64 (overdrive) and

= 64/44 (underdrive) assuming that the moments of inertia

,

,

are 0.02

, 0.004

and 0.007

, respectively. The first situation represents the following conditions: the left gear has to be shifted; the counter shaft is at a standstill while the rotating speed of the output shaft is controlled to keep the value 300 rpm, which results in the initial

equal to −300 rpm on both sides; the friction torques

,

,

are 1 Nm, 0.25 Nm and 0.25 Nm, respectively. In the second situation, the right gear has to be shifted while the initial value of

is 2180 rpm, and the output shaft is controlled to rotate at a speed of 1000 rpm, resulting in the initial relative speeds equal to 2171 rpm on the left side and 500 rpm on the right side; the friction is assumed to have the following values:

=1.5 Nm,

=0.7 Nm,

=0.4 Nm. The simulation results are shown in

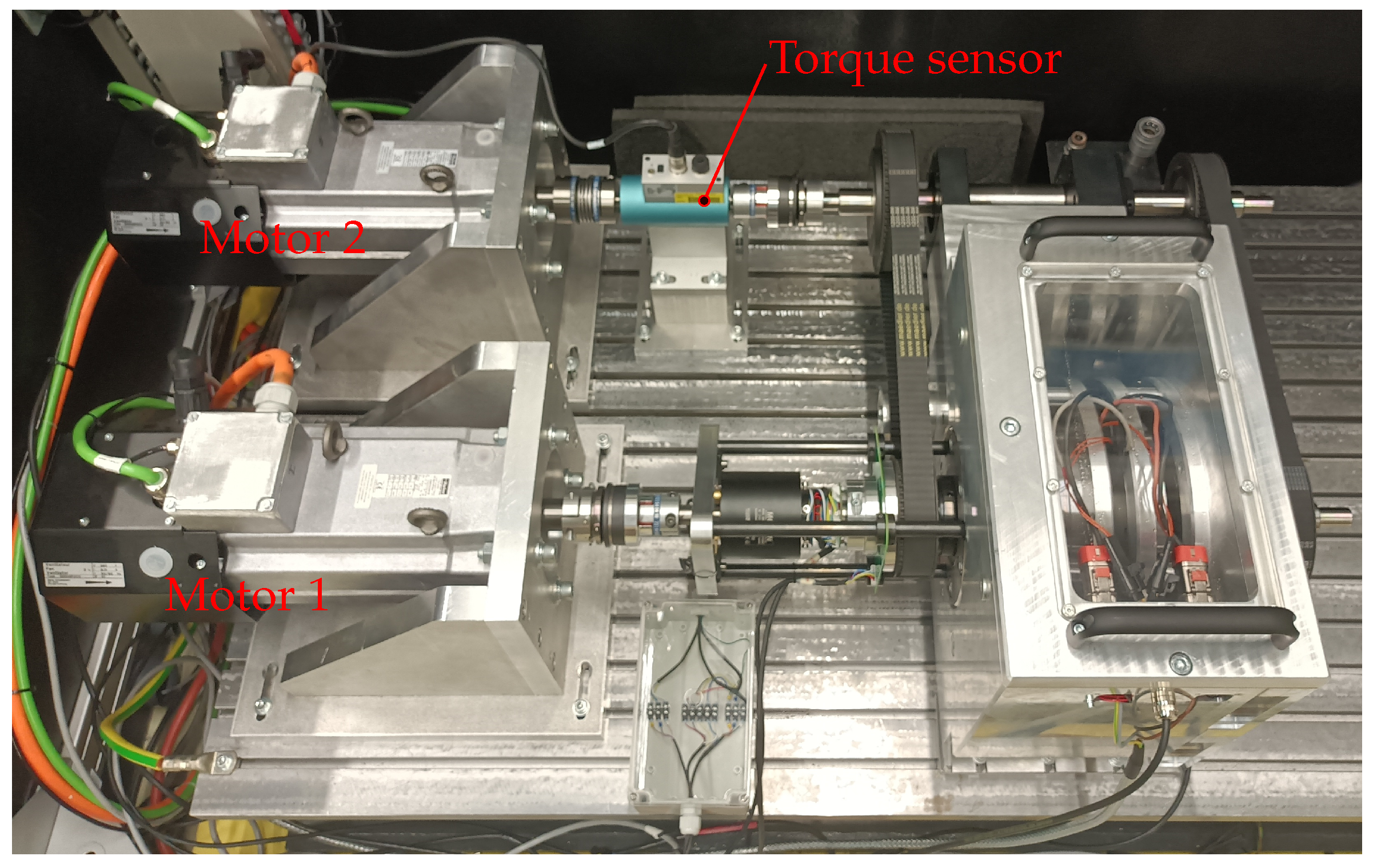

Figure 6 and 7. In both cases, the relative speeds could be synchronized without a significant displacement of the sleeve from the central position. Further, the required gears were shifted avoiding the face contact phase at the axial positions

x = −5 mm (left gear shifting) and

x = 5 mm (right gear shifting). The process of the experimental verification of the theoretical results is described in the next section.

6. Conclusions

The LREA presented earlier in [

40] was modified to allow its application as a double-sided dog clutch in automotive gearboxes. In contrast to common dog clutches, the developed double-sided clutch demonstrates the possibility of the rotation speed synchronization without an external torque source, while its design remains simple and reliable. The actuator can be integrated between two gearwheels of a gearbox. The speed difference is reduced electromagnetically without mechanical contact between the parts, which is a big advantage comparing to common synchronizers.

In rotary operation, the electromagnetic torque generated by the LREA reduces the initial speed difference to a small positive value, which is than used to reach the relative angle between the teeth of the sleeve and the slots of its counterpart where a direct teeth engagement is possible. In linear operation, the selected gear can be engaged or disengaged using the axial reluctance force generated by the LREA. Shifting of non-neutral gears starts at the relative angle reached in the rotary operation, so that the teeth are directly engaged. Thus, an axial contact of the teeth at unaligned positions, which can lead to unsuccessful shifting, is avoided.

A special control algorithm developed for rotary operation allows the compensation of the axial force which arises during the speed synchronization by a simultaneous excitation of the coil on the opposite side and adjustment of the coil currents depending on the corresponding relative angle. Thus, the shift sleeve remains in neutral gear until the appropriate shifting conditions are reached. The synchronizing torque is always generated on the side with a lower speed difference, which is named as synchronizing side, while the opposite is named as compensating side and creates the balance of the axial forces. The average value of the collateral torque on the compensating side is approximately zero. The sides can be switched during the synchronization depending on their relative speeds. The time of the current rise/fall is taken into account to adjust the excitation angles. The residual force difference can be compensated by the spring-loaded balls placed under the shift sleeve. At lower currents, the current adjustment is not required since the force changes slightly with the change of the relative angle. The voltages are applied to the coils based on the difference between the required and measured currents using a simple control method common for reluctance machines.

Since the gearwheels have different sizes and are interlocked with the same countershaft, the resulting friction torque is always higher on the bigger gearwheel. It makes its acceleration more difficult comparing to the smaller gearwheel. The actuator must be able to generate an average torque that is higher than the resulting friction torque to accelerate the gearwheel, while its braking is always possible since the actuator torque and the friction torque work in the same direction. The simulations show that, in principle, positive and negative speed differences can be reduced by the electromagnetic torque of the actuator while the shift sleeve remains in neutral gear. Moreover, a direct engagement of the teeth with the slots during gear shifting is possible on both sides.

To verify the theoretical results, a prototype of the double-sided dog clutch and a testing gearbox were designed and manufactured. The assembled gearbox with the integrated clutch was installed on a testrig with two motors, which can rotate the output shaft and the countershaft at different speeds. The experimental results show that the average electromagnetic torque generated by the actuator strongly reduces with the increase of the relative speed on the synchronizing side. This problem can be solved if the coils will be supplied with a higher voltage (the maximum voltage was limited to 70 V by the available electronic control unit). Further, pre-synchronized gear shifting was tested experimentally for both gears. Negative and positive differences between the rotation speed of the gearwheel and the shift sleeve could be reduced by the actuator without a significant displacement of the shift sleeve from the central position. In all four cases, the required gear was shifted without an axial contact between the shift sleeve and the corresponding complementary ring at unengaged state.

In the following publications, we will present algorithms that can make sensorless operation of the clutch possible.