Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The Physics of Ultrafine Particles

1.3. Sources and Concentrations of Ultrafine Particles

1.4. Respiratory Deposition of Ultrafine Particles

1.5. Topographic Influences

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Justification for Using Morgantown, WV, as a Surrogate Site

2.2. Study Locations

2.2.1. Brockway Avenue (Surrogate for Rough and Complex Topography)

2.2.2. Beechurst Avenue (Surrogate for Flat Topography)

2.2.3. Air Quality Monitoring and Instrumentation

2.3. The TSI MODEL 3910 NanoScan SMPS

2.4. Traffic Data Collection and Classification

2.4.1. Traffic Patterns Analysis

2.4.2. Configuration and Inputs for the Deposition Modelling

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Data Processing

2.6. MPPD Data Analysis

3. Results

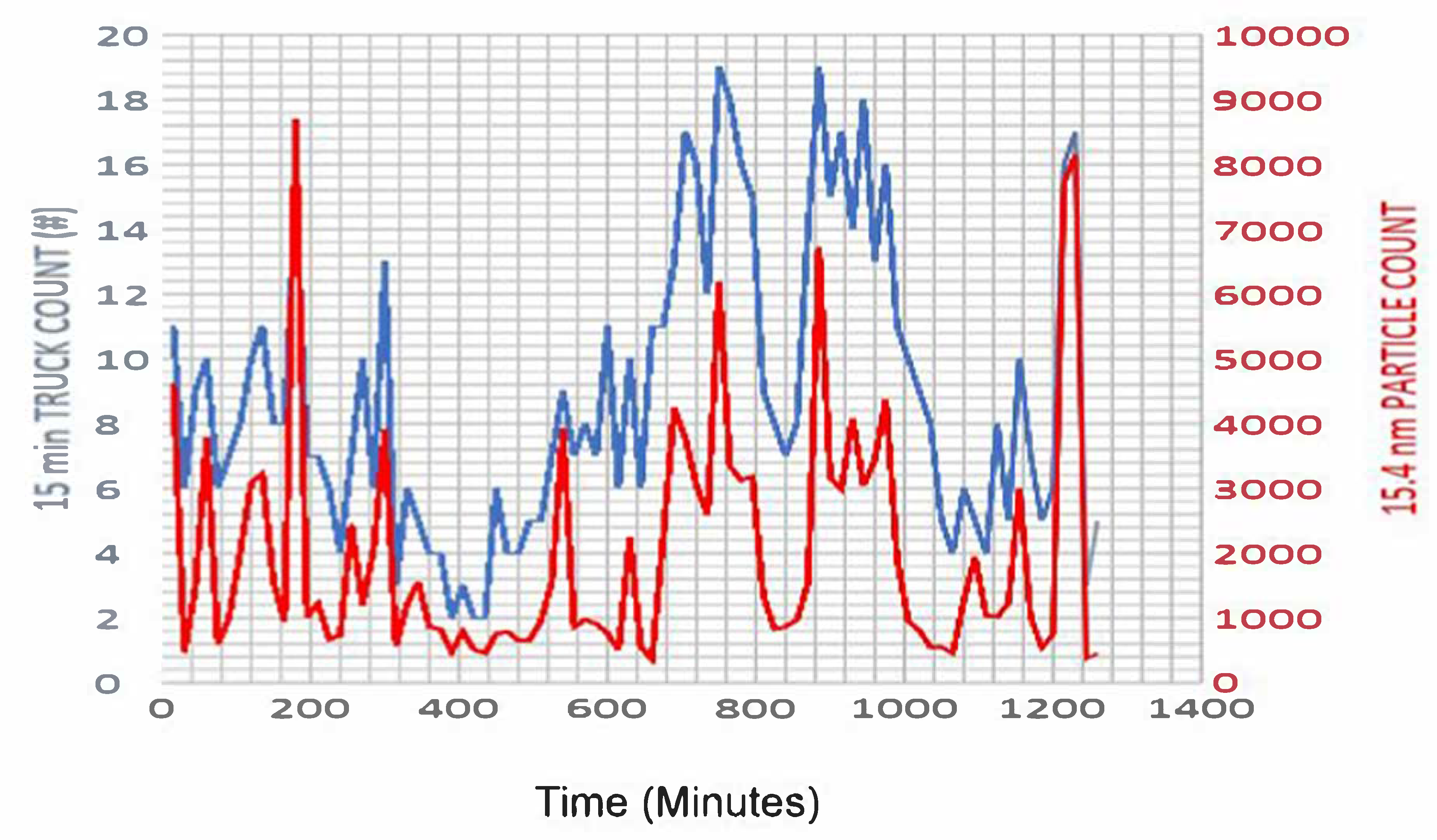

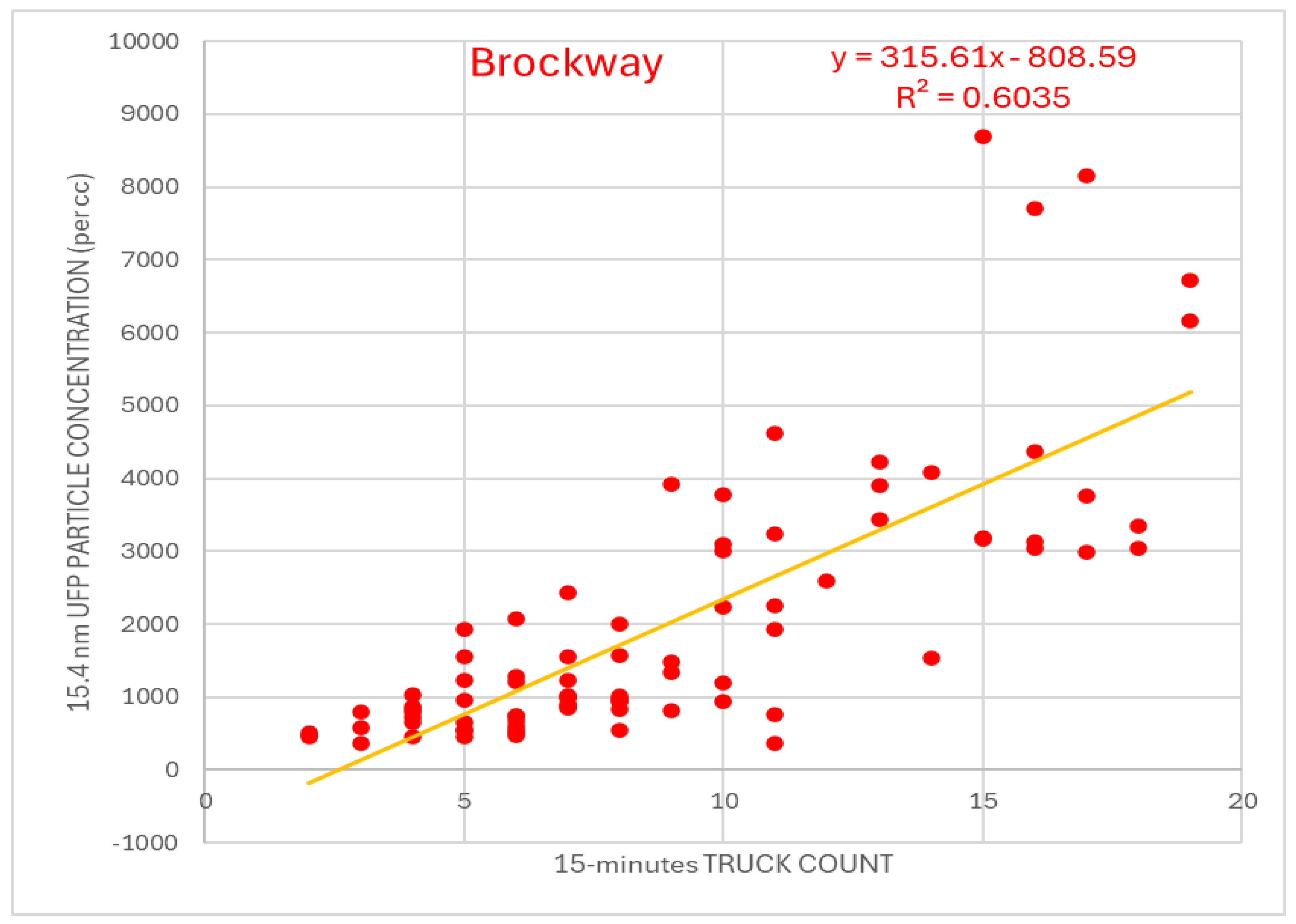

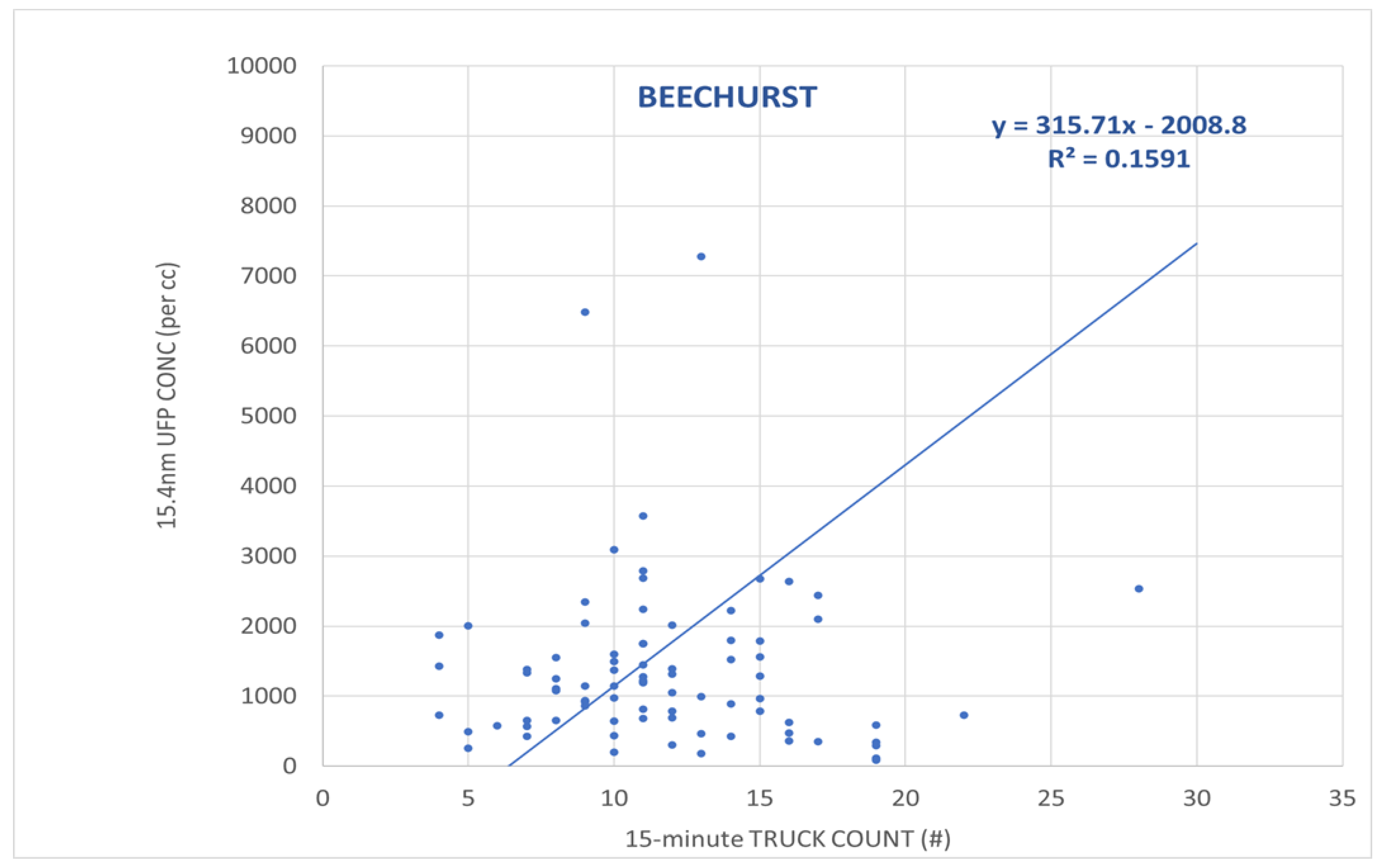

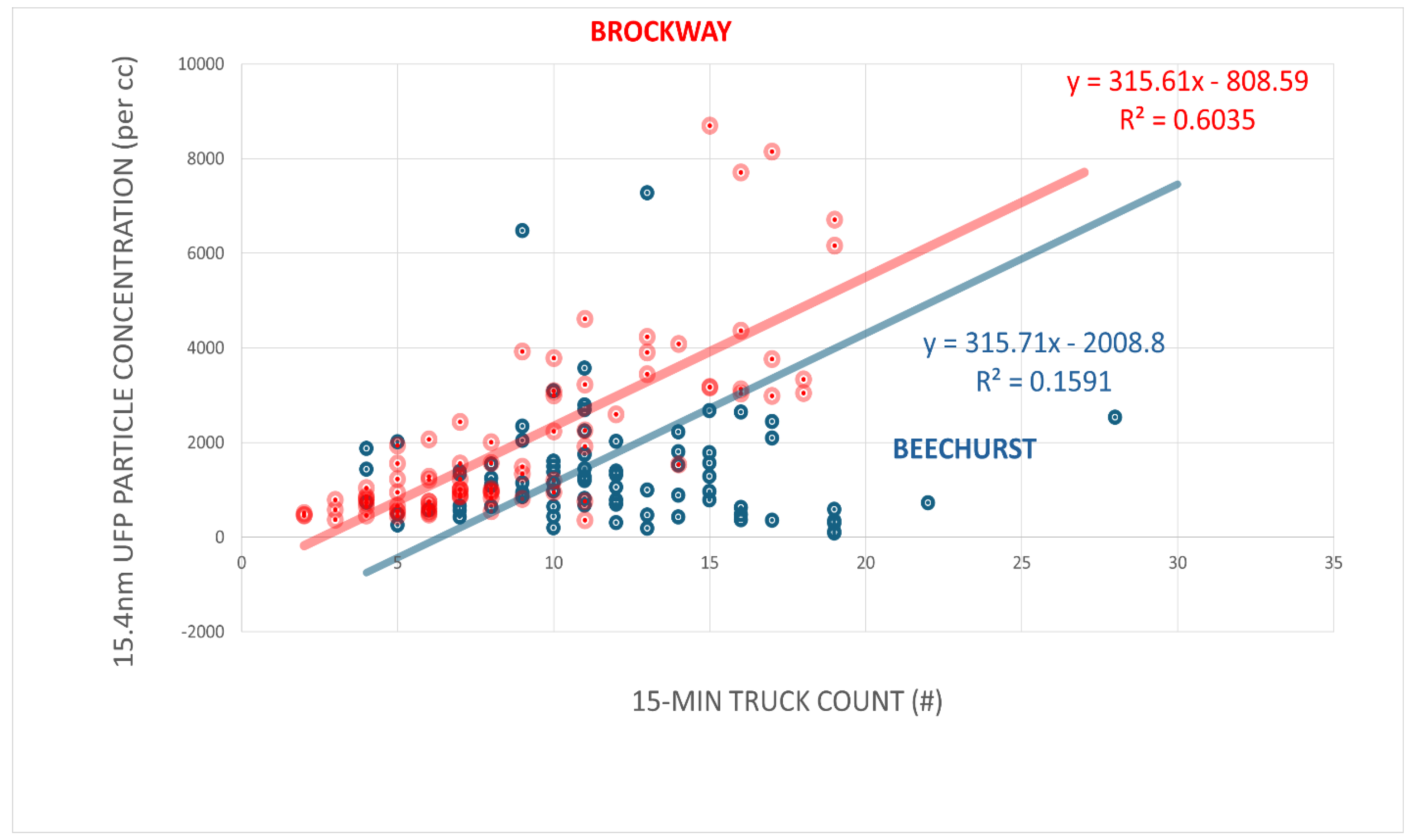

3.1. Time-Series Plot Analysis of Temporal Trends in Truck Traffic and UFP Levels

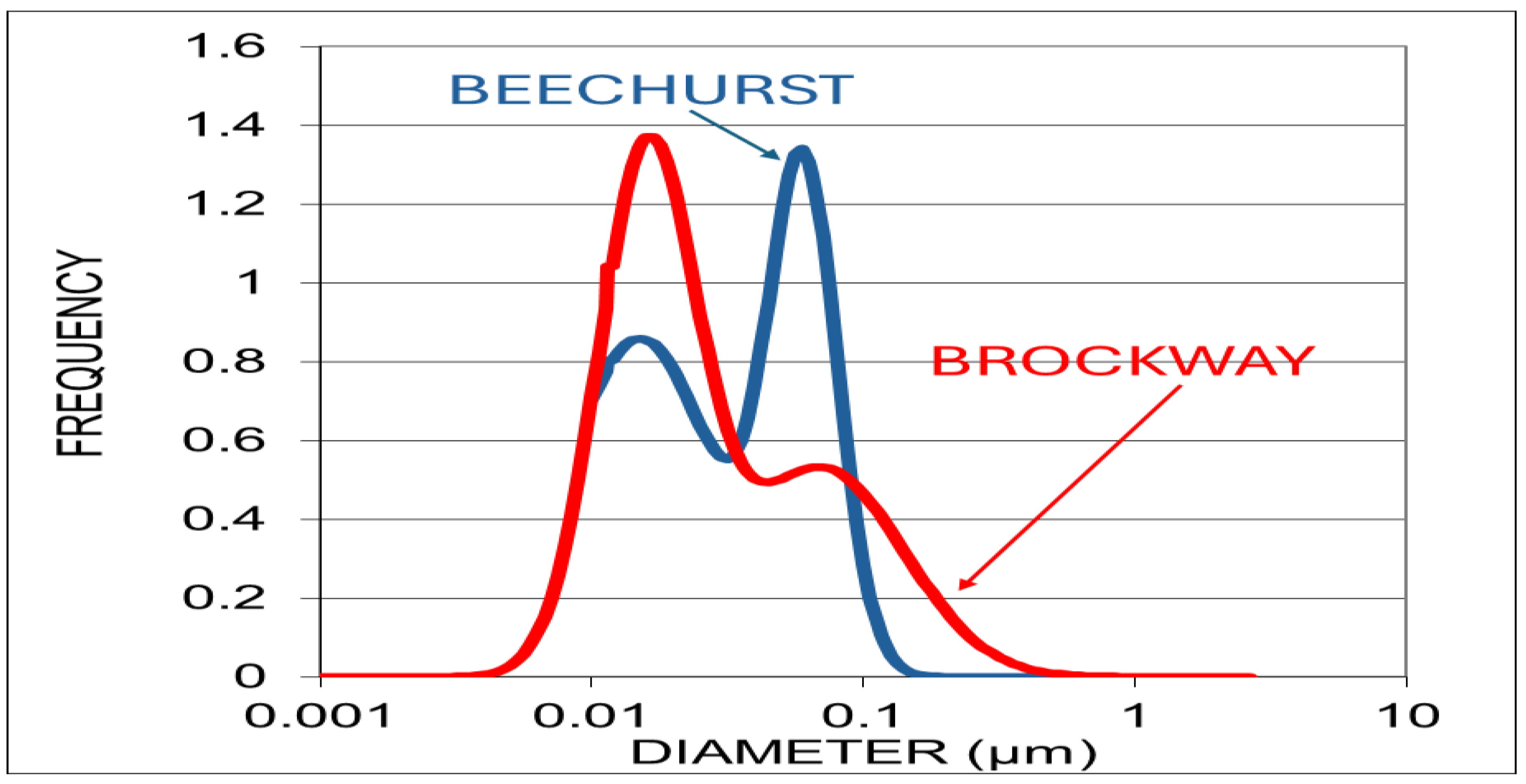

3.2. Analysis of Particle Size Distribution at Brockway and Beechurst and Its Implication for Lung Dose Estimation Using a Deposition Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Future Directions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Fuller, R.; et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. The Lancet Planetary Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcella, S.; et al. Size-based effects of anthropogenic ultrafine particles on activation of human lung macrophages. Environ Int 2022, 166, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.U.; et al. Pollution characteristics, mechanism of toxicity and health effects of the ultrafine particles in the indoor environment: Current status and future perspectives. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 436–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Ayala, A. Air Pollution, Ultrafine Particles, and Your Brain: Are Combustion Nanoparticle Emissions and Engineered Nanoparticles Causing Preventable Fatal Neurodegenerative Diseases and Common Neuropsychiatric Outcomes? Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 6847–6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presto, A.A.; Saha, P.K.; Robinson, A.L. Past, present, and future of ultrafine particle exposures in North America. Atmospheric Environment: X 2021, 10, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.L.; et al. Short-term exposure to ultrafine particles and mortality and hospital admissions due to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Copenhagen, Denmark. Environ Pollut 2023, 336, 122396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.-S.; Ryu, M.H.; Carlsten, C. Ultrafine particles: unique physicochemical properties relevant to health and disease. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2020, 52, 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, M.A. Does increased traffic flow around unconventional resource development activities represent the major respiratory hazard to neighboring communities?: knowns and unknowns. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2017, 23, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.M.R.d.S. Ultrafine particles: world characterization, occupational assessment and effects on human health. 2023, Universidade Fernando Pessoa.

- Lewis, A. ; D. Carslaw, and S. Moller, Ultrafine Particles (UFP) in the UK. 2018.

- Christian, W.J.; et al. Adult asthma associated with roadway density and housing in rural Appalachia: the Mountain Air Project (MAP). Environmental Health 2023, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.V.S.; et al. Review on Sampling Methods and Health Impacts of Fine (PM2.5, ≤2.5 µm) and Ultrafine (UFP, PM0.1, ≤0.1 µm) Particles. Atmosphere 2024. 15. [CrossRef]

- DeBolt, C.L.; et al. Lung Disease in Central Appalachia: It's More than Coal Dust that Drives Disparities. Yale J Biol Med 2021, 94, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlwein, S.; et al. Health effects of ultrafine particles: a systematic literature review update of epidemiological evidence. Int J Public Health 2019, 64, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaze, N.; et al. Assessment of the Physicochemical Properties of Ultrafine Particles (UFP) from Vehicular Emissions in a Commercial Parking Garage: Potential Health Implications. Toxics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, K.; Ramachandran, S.; Mishra, R.K. Seasonal variation of particle number concentration in a busy urban street with exposure assessment and deposition in human respiratory tract. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smichowski, P.; Gómez, D. An overview of natural and anthropogenic sources of ultrafine airborne particles: analytical determination to assess the multielemental profiles. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2023, 59, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groma, V.; et al. Sources and health effects of fine and ultrafine aerosol particles in an urban environment. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2022, 13, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K.; Feng, Y.; Dai, Q. Source apportionment of particle number concentrations: A global review. Sci Total Environ 2022, 819, 153104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.K.; et al. High-Spatial-Resolution Estimates of Ultrafine Particle Concentrations across the Continental United States. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 10320–10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; et al. Transport and deposition of ultrafine particles in the upper tracheobronchial tree: a comparative study between approximate and realistic respiratory tract models. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2021, 24, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; et al. Chemically Resolved Respiratory Deposition of Ultrafine Particles Characterized by Number Concentration in the Urban Atmosphere. Environ Sci Technol 2024, 58, 16507–16516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabani, N.V.S.; et al. Toxicity and health effects of ultrafine particles: Towards an understanding of the relative impacts of different transport modes. Environ Res 2023, 231, 116186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.D.; et al. Ultrafine particle exposure and biomarkers of effect on small airways in children. Environmental Research 2022, 214, 113860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; et al. Advances and highlights in asthma in 2021. Allergy 2021, 76, 3390–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.H.G.; et al. Occupational exposure and markers of genetic damage, systemic inflammation and lung function: a Danish cross-sectional study among air force personnel. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; et al. Personal exposure to average weekly ultrafine particles, lung function, and respiratory symptoms in asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents. Environment International 2021, 156, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.J.; et al. Prenatal Ambient Ultrafine Particle Exposure and Childhood Asthma in the Northeastern United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 204, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, B.; Kurian, G.A. , Exposure to real ambient particulate matter inflicts cardiac electrophysiological disturbances, vascular calcification, and mitochondrial bioenergetics decline more than diesel particulate matter: consequential impact on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 97518–97530. [Google Scholar]

- Lachowicz, J.I.; Gać, P. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Inhaled Ultrafine Particles on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; et al. Hidden danger: The long-term effect of ultrafine particles on mortality and its sociodemographic disparities in New York State. J Hazard Mater 2024, 471, 134317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; et al. Short-term effects of ultrafine particles on heart rate variability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution 2022, 314, 120245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnerero Quintero and, C. ; Dynamics of ultrafine particles and tropospheric ozone episodes. 2021, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.L. ; Air pollution in different microenvironments in Vietnam. PhD by Publication, Queensland University of Technology. 2022, Queensland University of Technology.

- Lv, W. ; Y. Wu, and J. Zang A Review on the Dispersion and Distribution Characteristics of Pollutants in Street Canyons and Improvement Measures. Energies, 2021. 14. [CrossRef]

- Goodsite, M.E.; et al. Urban Air Quality: Sources and Concentrations, in Air Pollution Sources, Statistics and Health Effects, M.E. Goodsite, M.S. Johnson, and O. Hertel, Editors. 2021, Springer US: New York, NY. p. 193-214.

- Kuang, A.S.C. ; Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) Instrument Handbook. 2024: U.S. Department of Energy, Atmospheric Radiation Measurement user facility, Richland, Washington. DOE/SC-ARM-TR-147.

- Kaleb Duelge, G.M.; Hackley, V.A. Michael Zachariah, Accurate Nanoparticle Size Determination using Electrical Mobility Measurements in the Step and Scan Modes. Aerosol Science and Technology 2022, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; et al. Design and Experimental Validation of a High-Resolution Nanoparticle Differential Mobility Analyzer. Instruments and Experimental Techniques 2023, 66, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.R. ; Characterization of Scanning Mobility Particle Sizers for Use with Nanoaerosols. 2018: University of South Florida.

- Jakubiak, S.; Oberbek, P. Determination of the Concentration of Ultrafine Aerosol Using an Ionization Sensor. Nanomaterials, 2021. 11. [CrossRef]

- TSI, NANOSCAN SMPS Nanoparticle Sizer Model 3910, Expanding Nanoparticle Measurement Capabilities. 2023.

- Shirman, T.; Shirman, E.; Liu, S. Evaluation of Filtration Efficiency of Various Filter Media in Addressing Wildfire Smoke in Indoor Environments: Importance of Particle Size and Composition. Atmosphere, 2023. 14. [CrossRef]

- Liati, A.; et al. Ultrafine particle emissions from modern Gasoline and Diesel vehicles: An electron microscopic perspective. Environ Pollut 2018, 239, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazneen, et al. Assessment of seasonal variability of PM, BC and UFP levels at a highway toll stations and their associated health risks. Environ Res 2024, 245, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahlhofen, W.; Rudolf, G.; James, A.C. Intercomparison of Experimental Regional Aerosol Deposition Data. Journal of Aerosol Medicine 1989, 2, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, P. ; Limitations in the Use of Particle Size-Selective Sampling Criteria in Occupational Epidemiology. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 1991, 6, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Borisova, K.R.; Pavlovska, I.; Martinsone, Ž.; Mārtiņsone, I. Multiple Path Particle Dosimetry Model Concept and its Application to Determine Respiratory Tract Hazards in the 3D Printing. ETR 2023, 2, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmes, J.R. and N.N. Hansel, Tiny Particles, Big Health Impacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 210, 1291–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnolo, D.; et al. In-vehicle airborne fine and ultra-fine particulate matter exposure: The impact of leading vehicle emissions. Environment International 2019, 123, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelson, D.B. ; Ultrafine particle emission & control strategies, in South Coast Air Quality Management District Conference on Ultrafine Particles: The Science, Technology, and Policy Issues. 2006: Wilshire Grand Hotel, Los Angeles.

- Hussain, R.; et al. Air pollution, glymphatic impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci 2023, 46, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; et al. Ultrafine particle deposition in a realistic human airway at multiple inhalation scenarios. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng 2019, 35, e3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).