Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Areas of Study and Their Peculiarities

2.1.1. Crati River

2.1.2. Corace River

2.1.3. The Fiumara Valanidi

2.2. Instruments Used for Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Aerial Photogrammetry

2.2.2. Aerial Laser Scanner (ALS)

2.2.3. Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS)

2.2.4. GNSS

2.2.5. Total Station

2.3. Methodologies Adopted for the Integration of Data

2.4. Integration of Datasets for Hydrological Modeling

- -

- Shared edges and overlapping zones were identified. Duplicate or closely spaced vertices within these areas were removed or averaged, and edge snapping was applied to ensure seamless connectivity.

- -

- The merged point set was re-triangulated to form a new TIN structure using Delaunay triangulation. Special attention was given to preserving terrain features and ensuring topological correctness, particularly in areas critical for water flow such as ridges and depressions.

3. Results

3.1. Orthophoto

3.2. Meshing of ALS and TLS Point Clouds

3.3. Multiresolution TIN

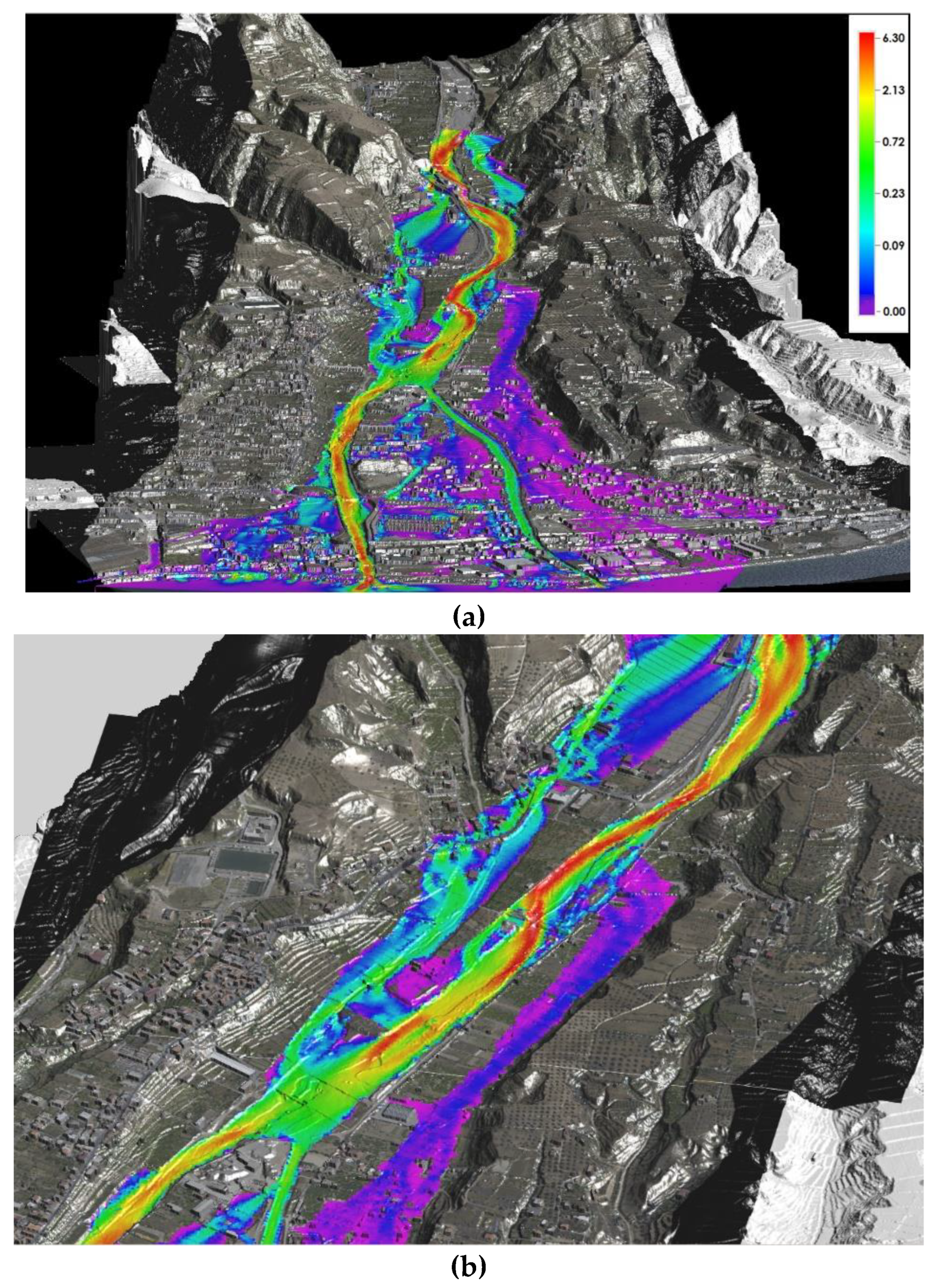

3.4. 2.5D Views per Rappresentazione dei Risultati

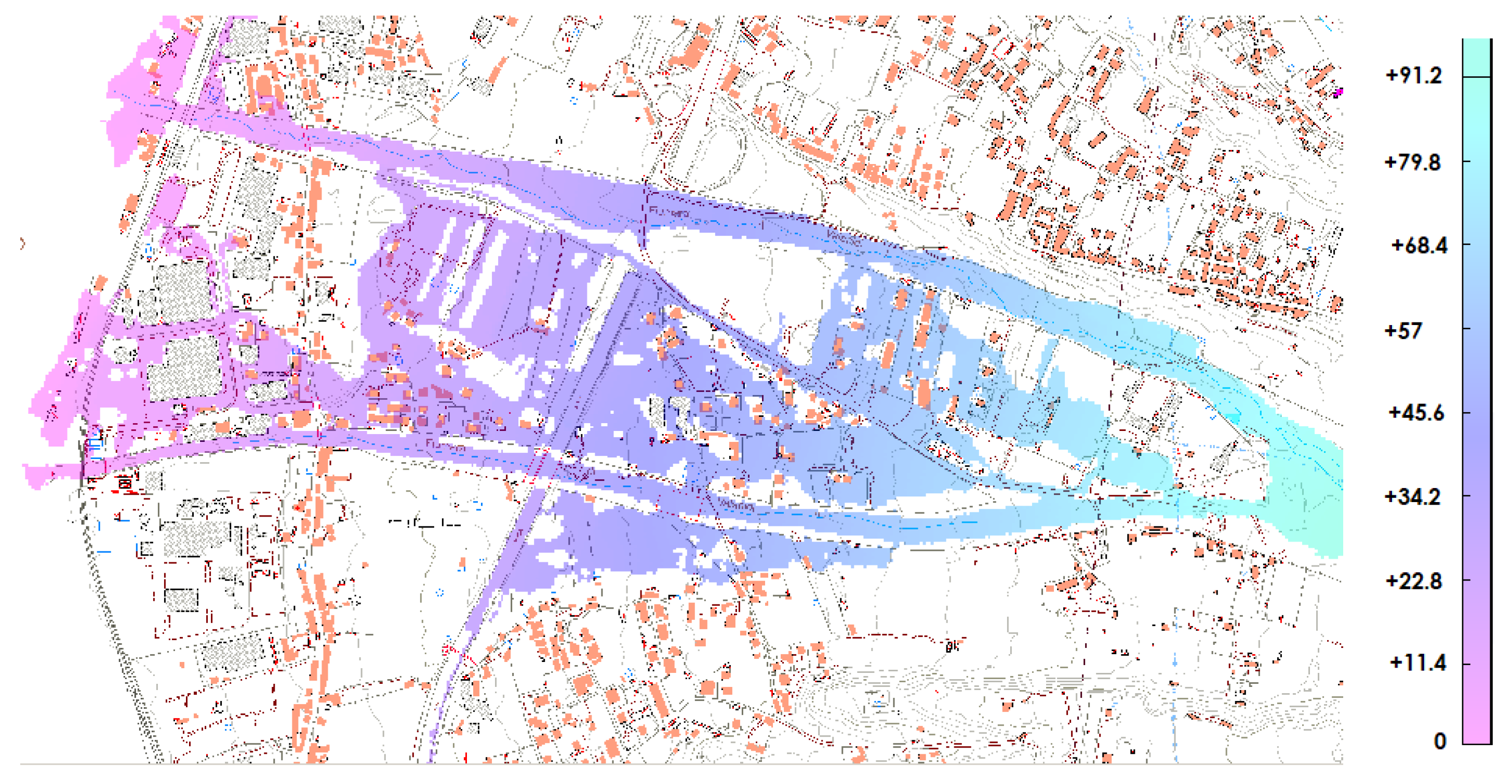

3.5. Representation of Results on the Regional Technical Map

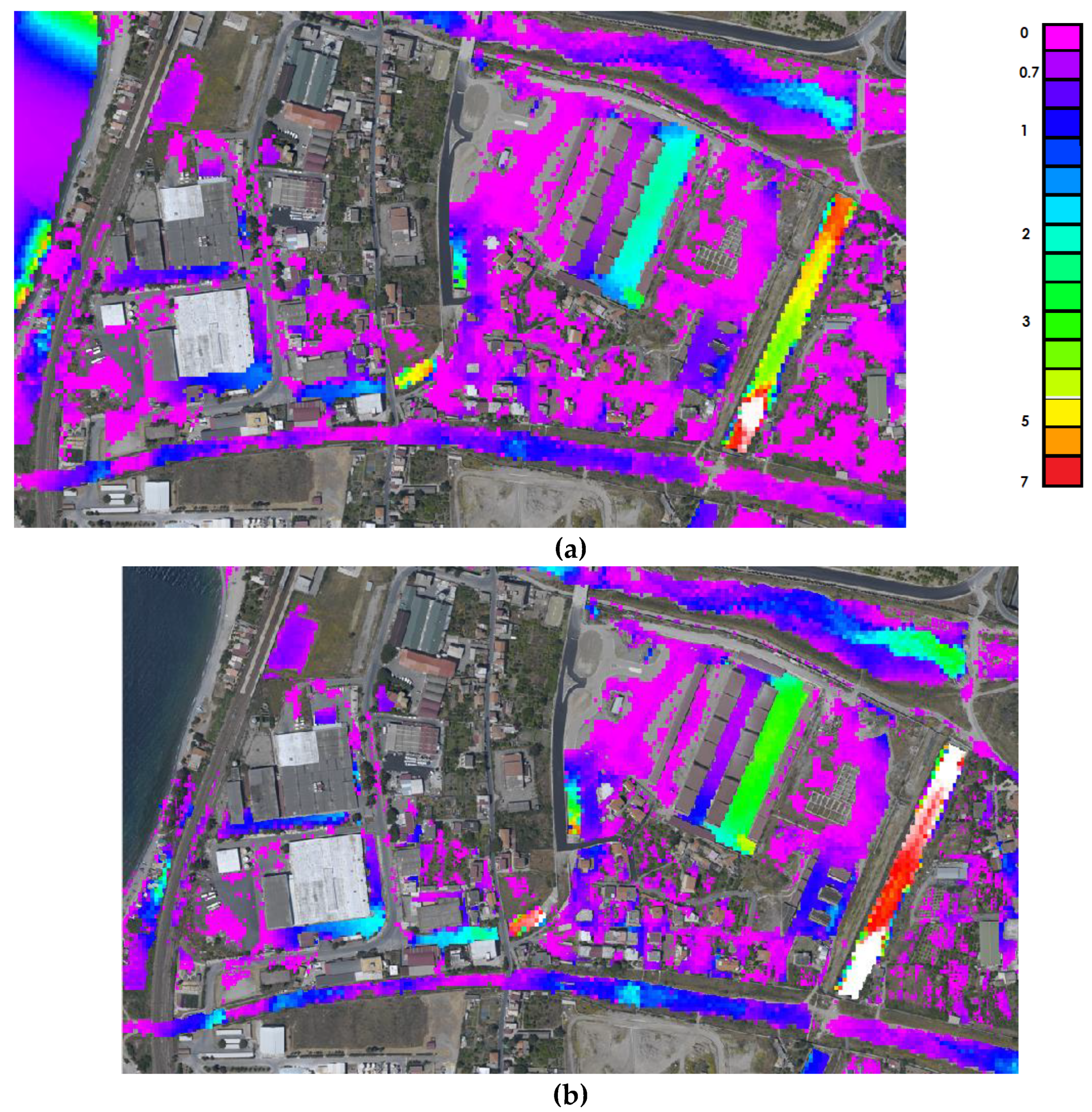

3.6. Representation on Orthophotos with Enhanced Detail

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Civil Protection Department of Italy: on the right side of the figure. Available online: https://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/it/approfondimento/descrizione-del-rischio-meteo-idrogeologico-e-idraulico/ (accessed on 15-4-2025).

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers Italian Civil Protection Department: National risk assessment Overview of the potential major disasters in Italy: seismic, volcanic, tsunami, hydro-geological/hydraulic and extreme weather, droughts and forest fire risks updated: December 2018. Available on line: https://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/static/ 5cffeb32c9803b0bddce533947555cf1/ Documento_sulla_Valutazione_nazionale_dei_rischi.pdf (accessed on 15/04/2025).

- Higher Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) Hydrogeological instability in Italy: hazard and risk indicators 2021 Edition. ISPRA Reports 356/2021. Available on line: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files2022/pubblicazioni/rapporti/rapporto_dissesto_idrogeologico_italia_ispra_356_2021_finale_web.pdf (accessed on 15/04/2025).

- Pleterski, Ž.; Hočevar, M.; Bizjan, B.; Kolbl Repinc, S.; Rak, G. Measurements of Complex Free Water Surface Topography Using a Photogrammetric Method. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4774. [CrossRef]

- Javernick, L.; Brasington, J.; Caruso, B. Modeling the topography of shallow braided rivers using Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry. Geomorphology 2014, 213, 166–182.

- Artese S, Perrelli M, Tripepi G, Aristodemo F. Dynamic measurement of water waves in a wave channel based on low-cost photogrammetry: description of the system and first results. In: R3 in Geomatics: Research, Results and Review; Parente, C., Troisi, S., Vettore, A. Eds.; Springer Nature, Berlin, Germany, 2019, Vol. 1246, p. 198.

- Szostak, R.; Pietroń, M.; Wachniew, P.; Zimnoch, M.; Ćwiąkała, P. Estimation of Small-Stream Water Surface Elevation Using UAV Photogrammetry and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1458. [CrossRef]

- Hohenthal, J., Alho, P., Hyyppä, J., & Hyyppä, H. Laser scanning applications in fluvial studies. Progress in Physical Geography 2011 35(6), 782-809. [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G., Pfennigbauer, M., Schwarz, R., and Pöppl, F. A decade of progress in topo-bathymetric laser scanning exemplified by the pielach river dataset. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1/W1-2023, 1123–1130. [CrossRef]

- Artese S. The Survey of the San Francesco Bridge by Santiago Calatrava in Cosenza, Italy. ISPRS-International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 33-37.

- Barbero-García, I.; Guerrero-Sevilla, D.; Sánchez-Jiménez, D.; Marqués-Mateu, Á.; González-Aguilera, D. Aerial-Drone-Based Tool for Assessing Flood Risk Areas Due to Woody Debris Along River Basins. Drones 2025, 9, 191. [CrossRef]

- Artese G., Fiaschi S., Di Martire D., Tessitore S., Fabris M., Achilli V., Ahmed A., Borgstrom S., Calcaterra D., Ramondini M., Artese S., Floris M., Menin A., Monego M., Siniscalchi V. Monitoring of Land Subsidence in Ravenna Municipality Using Integrated SAR-GPS Techniques: Description and First Results. ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2016, XLI-B7, 2016, pp.23-28, DOI 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLI-B7-23-2016.

- Backes, D., Smigaj, M., Schimka, M., Zahs, V., Grznárová, A., and Scaioni, M. River morphology monitoring of a small-scale alpine riverbed using drone photogrammetry and lidar. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII-B2-2020, 1017–1024. [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz, P., Siejka, M., & Mika, M. Assessment of the accuracy of DTM river bed model using classical surveying measurement and LiDAR: a case study in Poland. Survey Review 2019, 52(372), 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Artese, S., Perrelli, M., Rizzuti, F., Artese, F., Artese, G. The integration of a new sensor and geomatic techniques for monitoring the Roman bridge S. Angelo on the Savuto river (Scigliano, Italy). International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, IMEKO, Budapest, Hungary, 2022, pp. 191–195.

- Abrahart, R., See, L. M. Multi-model data fusion for river flow forecasting: An evaluation of six alternative methods based on two contrasting catchments Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2002, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- Brodu, N., & Lague, D. 3D terrestrial lidar data classification of complex natural scenes using a multi-scale dimensionality criterion: Applications in geomorphology. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2012, 68, 121–134.

- Uciechowska-Grakowicz, A.; Herrera-Granados, O. Riverbed Mapping with the Usage of Deterministic and Geo-Statistical Interpolation Methods: The Odra River Case Study. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4236. [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, P., Belmont, P., & Foufoula-Georgiou, E. Automatic geomorphic feature extraction from lidar in flat and engineered landscapes. Water Resources Research 2015, 51(3), 1794–1821.

- Pirotti, F., Guarnieri, A., Chiodini, S., and Bettanini, C. Automatic coarse co-registration of point clouds from diverse scan geometries: a test of detectors and descriptors, ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1/W1-2023, 581–587. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N., Qin, R., Song, S. Point cloud registration for LiDAR and photogrammetric data: A critical synthesis and performance analysis on classic and deep learning algorithms, ISPRS Open Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2023, Volume 8, 2023, 100032. [CrossRef]

- Barzaghi, R., Borghi, A., Carrion, D., Sona, G. Refining the estimate of the Italian quasi-geoid, Bollettino di Geodesia e Scienze affini 2007, 3, 145-160.

- Artiglieri, P., Curulli, G., Coscarella, F., Algieri Ferraro, D., Macchione, F. Performance of HEC-RAS v6.5 at basin scale for calculating the flow hydrograph: comparison with TUFLOW. Natural Hazards 2025, 121-3. [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P., Macchione, F., Natale, L., Petaccia, G. Flood mapping using LIDAR DEM. Limitations of the 1-D modeling highlighted by the 2-D approach. Nat Hazards 2015, 77, 181–204. [CrossRef]

- Macchione, F. (Scientific coordinator). Final reports of the POR Calabria 2000–2006 project “Methods for the Identification of Areas at Hydraulic Flood Risk” 2012, conducted in collaboration with CUDAM (University of Trento), the University of Pavia, and the National Institute of Oceanography and Experimental Geophysics – OGS (Trieste).

- Remondino, F., Rizzi, A. Reality-based 3D documentation of natural and cultural heritage sites—techniques, problems, and examples. Appl Geomat 2010, 2(3), 85–100, DOI 10.1007/s12518-010-0025-x.

- MeshLab. Available online: https://www.meshlab.net/ accessed on 10-02-2023.

- QGIS. Available online: https://qgis.org/ accessed on 10-02-2023.

- ER Mapper manual. Available online: https://www.planetek.it/media/download/er_mapper accessed on 10-02-2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).