Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Literature Review

- The effects of corporate agglomeration on investment, industrial growth and exports in developing countries

- II.

- Decision support tools for monitoring, evaluation and strategic planning of SEZs in developing countries:

- SEZ profitability assessment models

- 2.

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

- 3.

- Performance Scorecards (PSC)

- 4.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) models

- 5.

- Simulations and Modeling of Economic Impacts

- 6.

- SWOT analysis

- 7.

- SEZ Strategic Planning Methods

- 7.1.

- Participatory approach

- 7.2.

- Long-term planning and dynamic management

Methodology

- Existing approaches and methods and definition of the methodological approach for the Gabon case study

- Summary of studies on the effects of corporate agglomeration

- 2.

- Studies on the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on enterprise agglomeration, industrial growth and exports in developing countries.

| Aspect | Econometric methods used | Results | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Industrial growth | - Panel regression models (Fixed and Random Effects) - Granger cointegration and causality models | FDI has a positive effect on industrial growth, particularly in countries that attract quality FDI (advanced technologies, managerial know-how). | - Borensztein et al (1998) show that FDI has a positive impact on growth in developed countries, amplified by a high level of education. |

| 2. Company cluster | - Spatial Econometrics - Difference-in-difference (DID) methods | FDI favors the geographic concentration of companies, creating industrial clusters that improve efficiency and competitiveness. | - Javorcik (2004) shows that FDI in manufacturing favors agglomeration and leads to greater competitiveness and higher exports. |

| 3. Impact on exports | - Propensity Score Matching (PSM) models - Panel regression models | FDI improves local companies' access to world markets, boosting exports in sectors such as electronics and textiles. | - Blomström and Kokko (1998) show that FDI stimulates exports, particularly in export-oriented sectors (electronics, automobiles, textiles). |

- 3.

- Reference decision-support tools for monitoring, evaluation and strategic planning of SEZs in developing countries:

| Decision Support Tool | Method | Example |

|---|---|---|

| SEZ profitability assessment models | Discounted cash flow (DCF) method to assess the profitability of SEZs. | UNIDO model for quantifying the economic, social and environmental benefits of SEZs. |

| Geographic information systems (GIS) | Collection and analysis of spatial data to optimize location and resource allocation. | Case studies in Africa and Asia to determine suitable areas for setting up SEZs (Kuroda et al., 2012). |

| Performance dashboards (BSC) | Ongoing monitoring of performance indicators (jobs, exports, quality of business environment). | Application of BSC in Bangladesh and Nigeria to improve strategic management of SEZs. |

| Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) models | Calculation of infrastructure costs and tax incentives, compared with profits generated. | Applying CBA in sub-Saharan Africa to compare costs and employment impacts (Hinkle et al., 2011). |

| Simulations and modeling of economic impacts | Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models to simulate the economic effects of SEZs. | CGE model used to study the impacts of SEZs in Asia and Africa (Lall et al., 2004). |

| SWOT analysis | Identification of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats affecting SEZs. | Using SWOT analysis to assess SEZs in Africa, focusing on governance and infrastructure (Farole & Akinci, 2011). |

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Participatory approach | Involve all stakeholders (government, business, local community) in the planning process. | Study on SEZs in India, highlighting the importance of participation in ensuring effectiveness (Sharma et al., 2015). |

| Long-term planning and dynamic management | Flexible strategies and periodic adjustments in response to economic and technological developments. | World Bank guidance for African SEZs, with periodic adjustments (World Bank, 2011). |

- To analyze the impact of company agglomeration on FDI, public investment, export revenues and industrial revenues in two distinct geographical areas of Gabon: the Nkok Special Economic Zone (SEZ) (homogeneous area) and areas outside this SEZ (heterogeneous area). The aim is to divide the forestry sector into two zones in order to highlight socio-economic and geographical disparities. The econometric approach uses the robust ordinary least squares (OLS) method to correct for estimation bias and problems of autocorrelation and normality of residuals, given the small temporal size of the sample (T=12).

- To study the impact of FDI and public investment on business agglomeration, export revenues and industrial income in these two geographical areas. The aim is similar to that of the first, to highlight the socio-economic and geographical differences between the Nkok SEZ and other areas of the country.

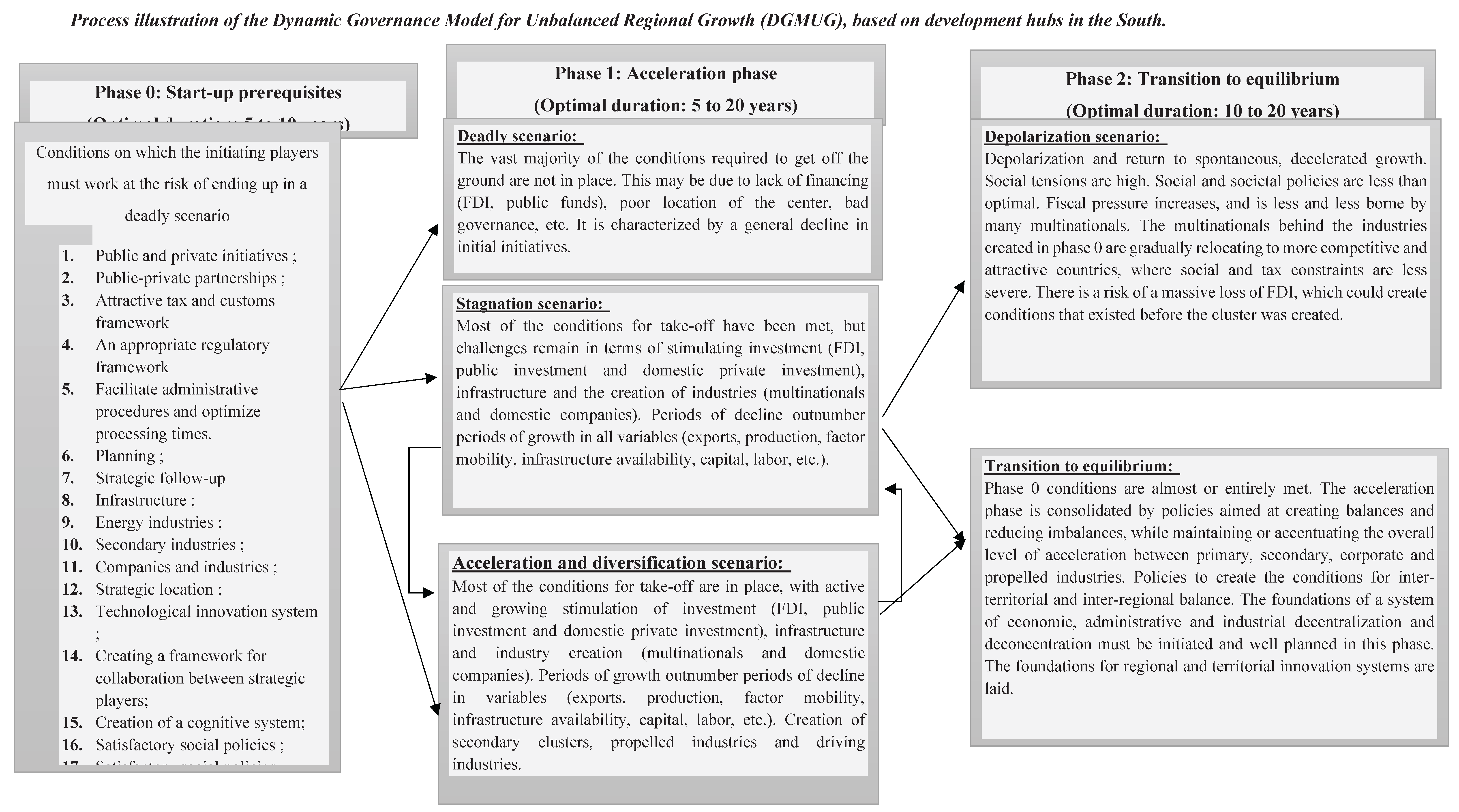

- Propose a governance model for unbalanced regional growth, focusing on endogenous growth, multinational FDI and public-private initiative. This model is based on the idea that unbalanced regional growth, associated with SEZs and development poles, can stimulate accelerated regional development, provided certain conditions are met. It aims to provide a decision-support tool for strategic planning of regional development policies, in particular the use of SEZs as levers for industrialization and sustainable development, thus strengthening the resilience and monitoring of development poles in developing countries.

- Modeling agglomeration effects

- Modeling the dynamic and static spatial effects of FDI associated with public investment

- The first model allows static and dynamic panel estimations with N =2 and T=9. The results of these estimations allow us to study the effects of the "In SEZ of Nkok" space on the "Macroenvironment" space;

- The second model allows static and dynamic panel estimations with N =2 and T=9. The results of these estimations allow us to study the effects of the "Out SEZ of Nkok" space on the "Macroenvironment" space;

- The third model allows static and dynamic panel estimations with N =3 and T=9. The results of these estimations enable us to study the simultaneous effects of the "In Free Zone" and "Out Free Zones" on the "Macroenvironment" space.

- Total industrial income in value terms is obtained by subtracting total income from non-industrial income. This means :

- Basic OLS regression model

- Y = (Investissement ,Direct , Étranger + Investissement , Public , Total (FDI + PITUSD. )

- Y(t) = The dependent variable

- X1 and X′1 = The sum total of industrial revenues in the forestry sector (Ind_P_TUSD).

- X2 and X′2 = Receipts from exports of forest products from Gabon (Exp_TUSD

- X3 and X′3 = Nomber of Companies in the forestry sector

- βi and β′i = Regression coefficients of independent variables

- β0 and β′0 = Original orders

- X is the matrix of observations of the explanatory variables;

- Y is the vector of observations of the dependent variable;

- X′ is the transposed X matrix.

- Correction for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation (HAC)

- is a robust estimate of the variance-covariance matrix of the estimated coefficients

- Where is the estimated residual

- The minimum individual and temporal dimensions are N=2 and T=2, which can be extended to infinity.

- The autoregressive (higher-order) model with lags P of the dependent variable and only minimal regularity conditions on the initial observations;

- The strictly exogenous repressors x itwith respect to the idiosyncratic error term are:

- For specific fixed and random effects on unobserved groups,

- Uncorrelated idiosyncratic errors in series are as follows:

Results

- Descriptive statistics

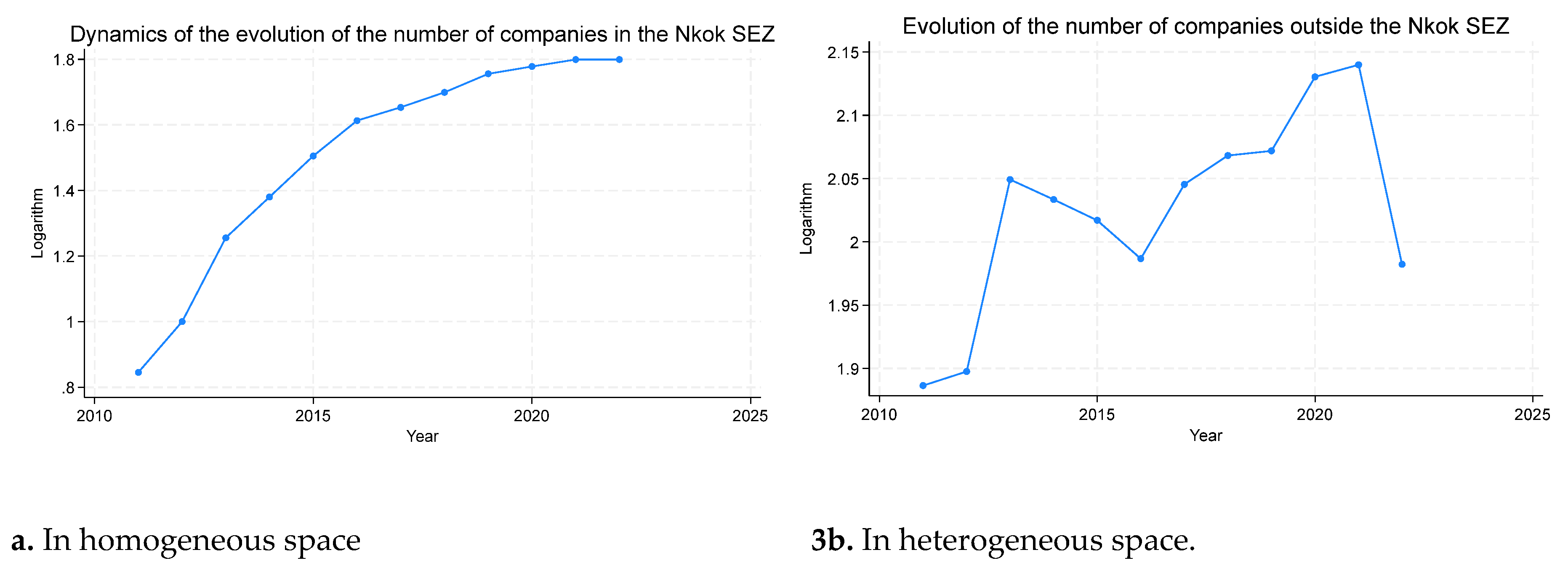

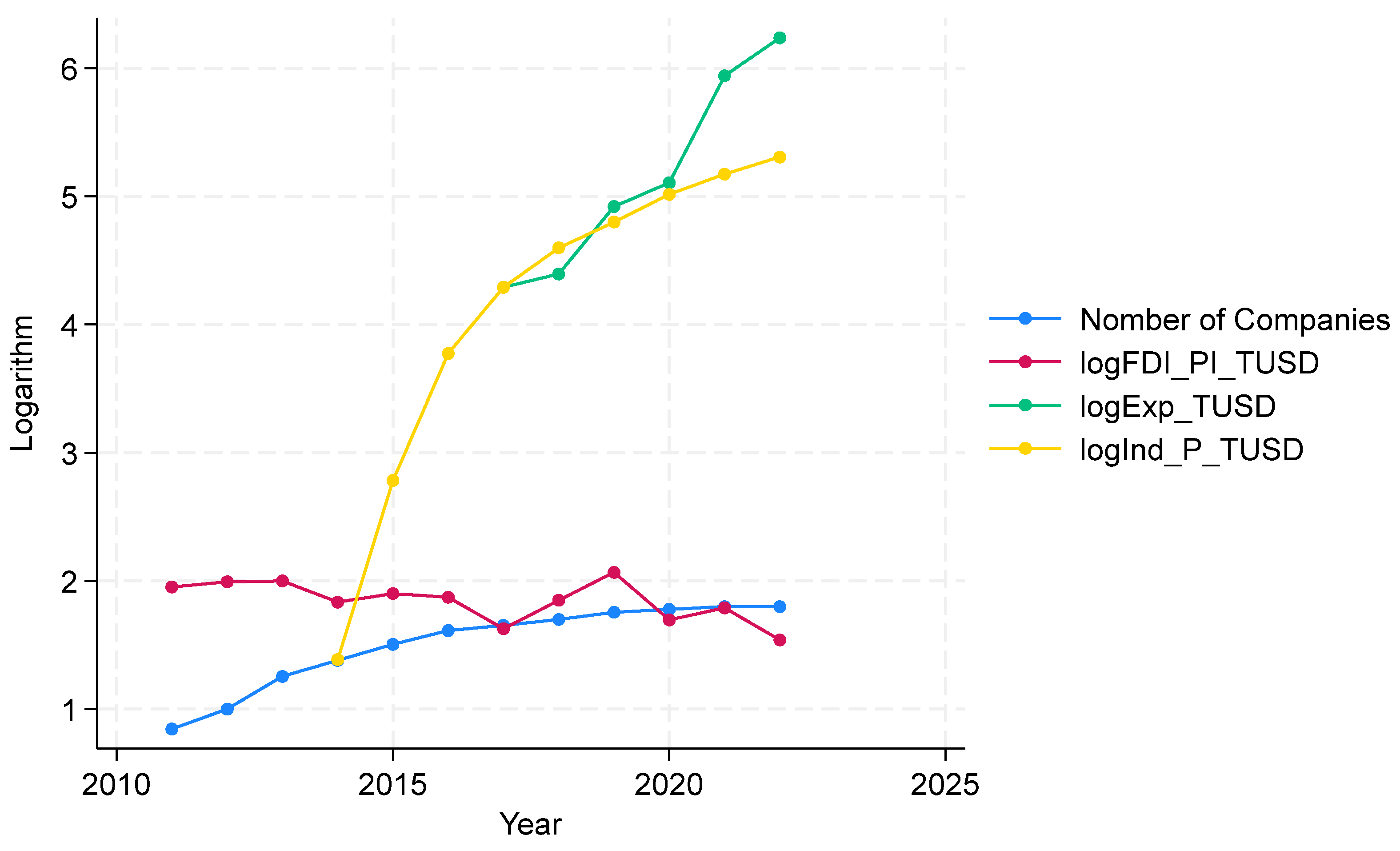

1.1. Description of variables in homogeneous space

-

Number of companies (blue curve):

- ○

- This curve shows the evolution of the number of companies in the forestry sector. It shows a significant increase from 2015 onwards, reaching strong growth after this year. The number of companies remains stable before 2015 and rises sharply in subsequent years.

-

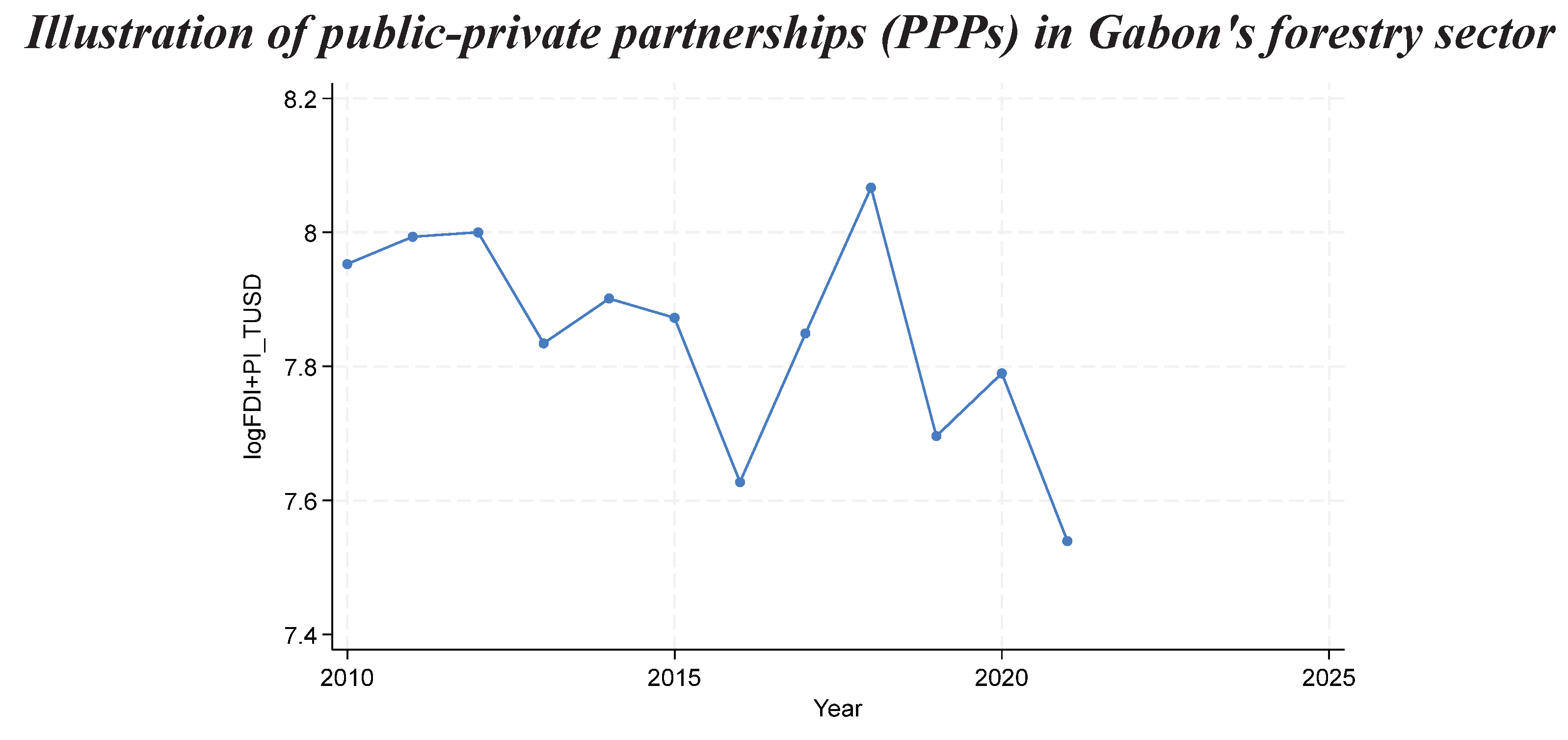

Foreign Direct Investment associated with public investment in Logarithm (LogFDI_PI_TUSD - Red curve):

- ○

- This curve shows the trend in foreign direct investment (FDI) in logarithmic form. It shows a slight upward trend, with a moderate increase between 2010 and 2020. However, the curve is not rising as fast as the number of companies, suggesting that foreign investment is growing at a slower pace.

-

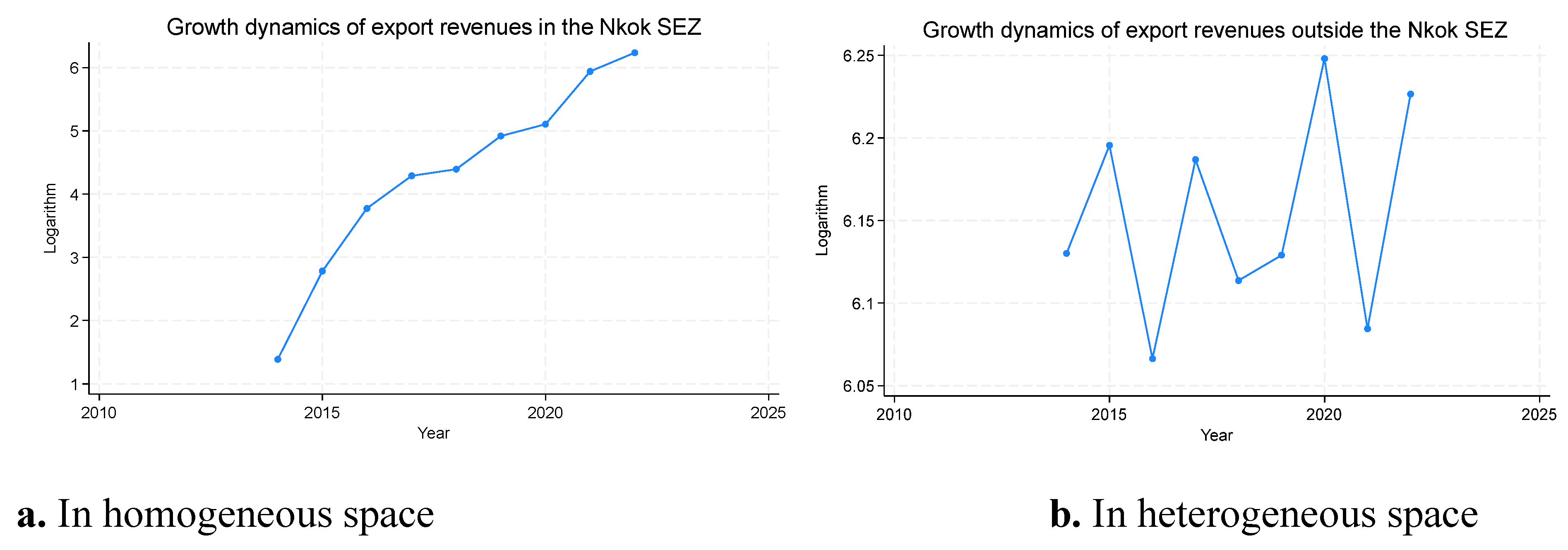

Logarithmic exports (LogExp_TUSD - Green curve) :

- ○

- This curve shows the development of exports in logarithmic form. It follows a general upward trend, indicating strong export growth from 2015 onwards, with a particularly marked peak around 2020. This probably reflects the growth of industrial production in the Nkok SEZ and its impact on exports.

-

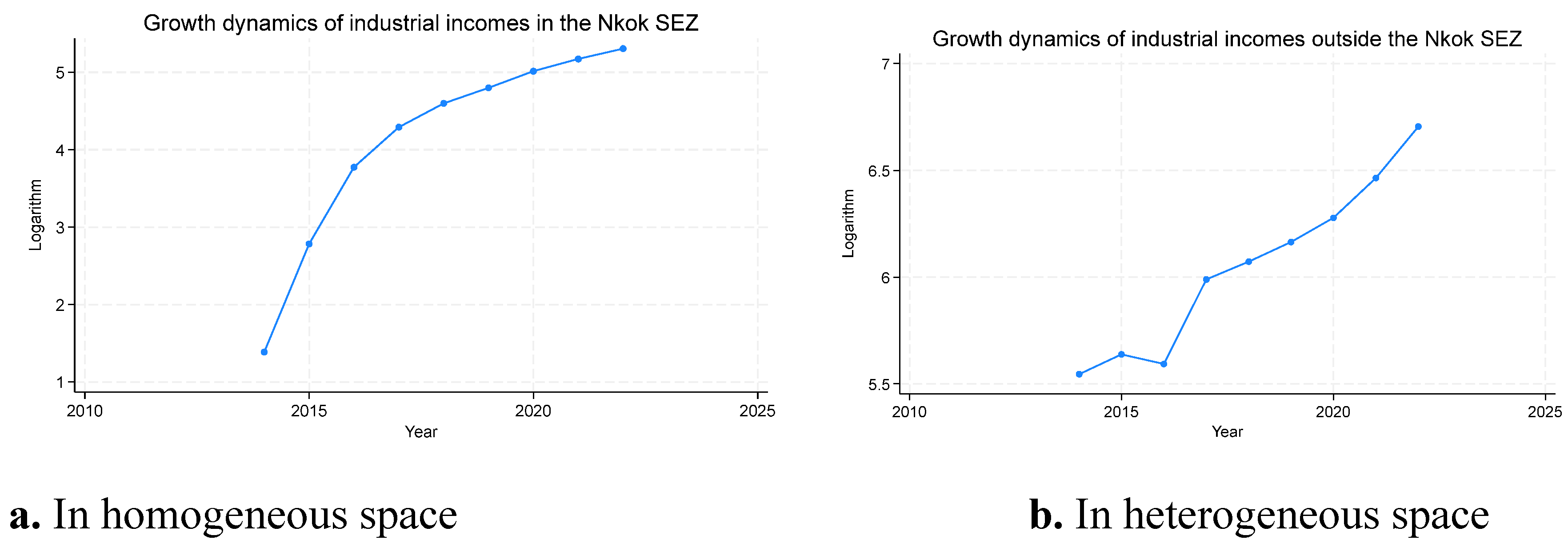

Log Industrial Income (LogInd_P_TUSD -Yellow curve):

- ○

- The yellow curve shows the trend in industrial revenues, also in logarithmic form. It shows a very sharp increase, especially from 2015 onwards, reflecting the effect of the "Big Push" on industrial production in the Nkok SEZ. This curve has the steepest slope, indicating a high rate of growth in industrial revenues over the years.

1.2. Description of variables in heterogeneous space

-

Foreign direct investment associated with public investment (LogFDI_PI_TUSD: Blue curve):

- ○

- This curve shows the evolution of foreign direct investment (FDI). It shows little variation over the years, remaining stable at a relatively low level. The increase is minimal, and there is no significant change in this curve until 2025, indicating little dynamism in foreign investment over the period studied.

-

Number of companies (red curve):

- ○

- The red curve shows the number of companies. Although this curve shows a slight upward trend, it remains stable overall, with few fluctuations. The number of companies does not seem to have increased significantly over this period, which contrasts with the more marked evolution of other indicators.

-

LogExp_TUSD (Green curve) :

- ○

- The green curve shows exports in logarithmic form. It shows a moderate upward trend, but more pronounced than that of foreign investment and the number of companies. There is a visible increase in exports from 2015 onwards, indicating a gradual growth in export activity.

-

LogInd_P_TUSD (Yellow curve):

- ○

- The yellow curve represents industrial revenues. This curve shows steady and relatively rapid growth from 2015 onwards. It follows an almost linear upward trend, reaching higher values compared to the other curves, reflecting a strong increase in industrial revenues over the years.

- Public and private initiatives: proactive and assertive government leadership in the face of the power of multinational corporations (MNCs).

- Public-private partnerships: These must be fair and enable governments to make the most of FDI. Portfolios of alliances with multinational companies must be managed transparently, intelligently and efficiently, with ideas and strategies clearly identified by the governments of the countries concerned.

- Attractive tax and customs framework: tax exemption policies must be preceded by market studies of SEZs and FDI at international level, in order to offer tax advantages with optimum short-, medium- and long-term profitability for the countries concerned. Coopetition systems (coexistence between cooperation and competition) must be set up between cluster initiators in developing countries.

- Appropriate regulatory framework: it must be stable over time in order to reassure investors. In particular the holders of FDIs.

- 5. Simplify administrative procedures and optimize processing times.

- Strategic planning: using the unbalanced growth model proposed by this study to help conceptualize the future balanced growth model.

- Strategic monitoring of international and national markets: necessary to obtain essential strategic information to increase visibility and improve governance and competitiveness. It must be carried out periodically and on an ongoing basis.

- Infrastructure: in strategic locations to stimulate growth and attractiveness.

- Driving industries: ensuring the creation and attractiveness of multinational and national companies.

- Secondary industries: Secondary industries should support the driving industries in peripheral regions or regions far from the main centers (homogeneous areas).

- Propelled companies and industries: organize upstream and downstream industries; vital for the activities of propelled companies and therefore the polarization of growth;

- Strategic locations: hubs should be close to population centers and land-based infrastructures such as airports, ports, power grids, etc.

- Innovation systems: These need to be conceptualized by host governments. Technology transfer strategies planned by host governments must create the conditions for capturing, absorbing and managing innovation in the short, medium and long term. These strategies must lay the foundations for creative and synthetic innovation;

- Creating a framework for collaboration between strategic players: strategic players must include governments, decentralized administrations, multinational companies, national companies, development partners, research laboratories, incubators and higher education establishments. The collaborative framework must give rise to a system of governance within and between each cluster (coordination of governance between localized economic spaces). The main clusters, secondary clusters and secondary economic systems theorized by Milton Santos (1974) [32], as well as the rest of the propelled industries, must all be interconnected by an inter-cluster participative governance model. The inter-pole governance system must be associated with a second governance system that incorporates a geographical dimension. This is the inter-territorial and inter-regional governance system. The inter-territorial governance system must involve players from all territorial levels within the same country. The inter-regional governance system, on the other hand, must involve players from homogeneous regions (with similar economic and geographic profiles) within the same country, right up to the economic communities of sub-regional and regional states.) However, these organizational dynamics need to be established over the long term in the regions of developing countries.

- Create a cognitive system: set up R&D programs, think tanks and working groups made up of strategic players, and build up universities, laboratories and research centers. Setting up support systems for innovative entrepreneurship in each homogeneous economic area (clusters or SEZs). Support systems for innovative entrepreneurship, including incubators, gas pedals and business developers, need to be set up. These programs should be supported by certified strategic partners in the area.

- Satisfactory social policies: these must be implemented to reduce and prevent tensions and inequalities within companies, and enable a gradual improvement in working conditions. Participative governance methods need to be implemented in companies.

- Satisfactory societal policies: must be implemented to reduce and prevent tensions and inequalities within the territories, regions and communities impacted by the clusters. They must also enable the implementation of participatory, inclusive and representative modes of governance in the regions impacted.

- Scenario 1: Deadly scenario

- Scenario 2: Stagnation scenario

- Scenario 3: Acceleration and industrial diversification scenario

- Scenario 1 :Depolarization scenario

- Scenario 2: transition to the equilibrium phase

- VIII.

- Summary of strategic criteria for the various phases and scenarios

-

Phase 0 : Start-up requirements

- ○

- This phase aims to lay a solid foundation for SEZs by establishing an attractive framework for investors.

- ○

- Tools such as SWOT analysis, profitability assessment models (UNIDO 2009), performance dashboards (BSC) and geographic information systems (GIS) are used to optimize planning, anticipate risks and maximize economic and social attractiveness.

- ○

- The focus is on strategic infrastructure, appropriate tax and regulatory policies, as well as innovation and collaboration between stakeholders.

-

Phase 1 : Acceleration

- ○

- At this stage, the growth of SEZs depends on the quality of investment and strategic management.

- ○

-

There are three possible scenarios:

- ▪

- Lethal scenario (project failure due to poor governance and insufficient funding).

- ▪

- Stagnation scenario (slower growth due to limited diversification and uneven infrastructure development).

- ▪

- Acceleration and diversification scenario (advanced industrialization and move upmarket into technology sectors).

- ○

- Tools such as CBA, BSC dashboards and economic simulations enable us to anticipate bottlenecks and adjust strategies in real time.

-

Phase 2 : Transition to equilibrium

- ○

- This phase aims to ensure the sustainability and stabilization of the SEZs.

- ○

-

Two scenarios may emerge:

- ▪

- Depolarization (loss of attractiveness of SEZs, resulting in the departure of multinationals and economic and social tensions).

- ▪

- Transition to equilibrium (increased independence of local industries and successful diversification).

- ○

- Tools such as strategic planning, GIS and economic impact modeling are used to monitor industrial diversification and reduce territorial imbalances.

Global summary

- Identify risks and opportunities.

- Optimize investments.

- Monitor performance.

- Ensure balanced growth by reducing spatial disparities and promoting industrial diversification.

- First major phase: Priority to the application of theories of unbalanced regional growth in underdeveloped regions, with particular attention to the contexts of globalization of production processes, FDI theory and international trade.

- Second major phase: Priority given to the application of balanced regional growth theories, with particular attention paid to the globalization of production processes, FDI theory, international trade, the internal regional specificities of the country in question, and the community space to which it belongs.

- Third major phase: In addition to the priorities of major phases 1 and 2, pay particular attention to new theories of territorialized economic and cognitive systems, hybrid cluster models adapted to the contexts of developing countries, and cluster labeling.

Discussion

- Geographic and social polarization: The results of this study highlight the economic polarization created by SEZs, particularly the Nkok SEZ, which concentrates investment and economic benefits to the detriment of peripheral areas. This polarization reinforces regional inequalities and can accentuate social tensions, particularly between industrialized urban areas and neglected rural areas. Political intervention is therefore needed to prevent uneven growth and promote a more equitable distribution of economic resources.

- Need for flexible regulations: The study reveals that foreign and public investment in the Nkok SEZ is tending towards saturation, suggesting that growth policies based solely on specific zones may not be sustainable in the long term. It is therefore crucial to put in place flexible regulations that allow for periodic adjustments to meet economic and technological challenges, while promoting balanced development in different geographical areas.

- Development of stronger public-private partnerships: Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the Nkok SEZ are showing signs of weakness after 2018, which may indicate a loss of dynamism in collaboration between public and private players. Stronger political involvement could reorient these partnerships to foster more inclusive and sustainable growth. It is necessary to encourage dynamic governance, capable of adapting to market changes and the needs of peripheral areas.

- Strengthening local governance: The governance of SEZs and development hubs needs to be strengthened through decentralized management, with local authorities and communities playing a key role in defining economic and social priorities. This could include stricter control mechanisms over how resources are allocated and used in these zones.

- Diversifying investment in peripheral areas: To counter the concentration of investment in SEZs and encourage more balanced growth, public policies should include incentives to attract investment to areas outside SEZs. This could include subsidies, tax breaks or low-interest loans to encourage companies to locate in less developed regions.

- Strengthening infrastructure in peripheral areas: Investment in transport, energy and communications infrastructure is essential to improve the attractiveness of peripheral areas. These infrastructures would not only facilitate access to local and international markets, but also contribute to better economic integration of remote regions.

- Improving natural resource management: In the forestry sector, it is crucial to adopt sustainable natural resource management practices to ensure that economic growth does not come at the expense of the environment. This includes environmental certification mechanisms, reforestation policies and the promotion of greener production technologies.

- Implementing the dynamic governance model: The proposed Dynamic Governance Model (DGMUG) could be a useful roadmap for developing country governments, particularly those in the South, to structure a more flexible and adaptable approach to regional growth. It is recommended that this model be tested in pilot areas to assess its effectiveness before being rolled out on a larger scale.

- Focus on endogenous growth and regional self-sufficiency: As a complement to foreign investment, policies must also support endogenous growth by promoting local entrepreneurship, innovation and capacity building for local businesses. This could include training programs, tax incentives and investment funds for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

- Concentration of investment in key areas without balanced redistribution in the global economy.

- Significant capital outflows limiting local growth.

- Stagnating investments due to industrial saturation.

- A lack of significant reinvestment in infrastructure development and support for local SMEs.

- Lack of diversification of economic activities outside the SEZ.

- Excessive dependence on multinational companies, which do not systematically reinvest their profits in the local economy.

- Export revenues do not directly stimulate local investment.

- A public strategy insufficiently focused on promoting long-term investment.

- Targeted tax incentives to encourage local reinvestment of FDI.

- Strengthening Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) to develop industrial and logistics infrastructures.

- Introduction of reinvestment requirements for multinational companies, making the granting of concessions conditional on a commitment to support local development.

- Creation of investment funds for the development of SMEs specializing in wood processing.

- Support for the structuring of local value chains to reduce dependence on raw material exports.

- Introduction of incentive policies to encourage companies to integrate local SMEs into their supply chains.

- Integration of sustainable development criteria in the granting of logging licenses.

- Promoting Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives to encourage investment in local strategic infrastructure.

- Encouraging companies to adopt local processing practices to increase the added value of exported products.

- Allocation of a significant proportion of tax revenues to development projects targeting local SMEs.

- Improved transparency in the collection and use of tax revenues to ensure effective financing of public investment.

- Adoption of alternative financing mechanisms, such as green bonds and sovereign wealth funds, to stimulate investment in the forestry sector.

Perspectives for Future Studies

- Assessing the long-term effects of SEZs: Longitudinal studies should be carried out to observe the long-term effects of SEZs on peripheral areas and the distribution of economic benefits. Such a study could offer insights into the sustainability of economic polarization strategies and provide empirical data for adjusting public policies.

- Comparative studies between different regions of the South: Comparing the development model based on SEZs and development poles with other African or developing regions could help explore the dynamics of growth and industrialization in different geographical and political contexts. Such studies could offer a more comprehensive view of best practices and pitfalls to be avoided.

- Modeling the transition to equilibrium: Phase 2 of the dynamic governance model proposes a scenario of transition to equilibrium. Future studies could deepen the modeling of this phase to better understand the factors of success or failure in the transition to a more balanced regional development. A detailed analysis of depolarization and successful transition policies in other contexts could provide practical guidelines.

- Studies on the social and environmental effects of SEZs: It is essential to complement the economic study with studies on the social and environmental effects of SEZs, particularly in sectors such as forestry. These studies could assess the impact of business agglomeration on local communities, the environment and the quality of life of people living in outlying areas.

- Impact of new technologies and innovation: With the rapid evolution of technologies, it would be relevant to explore how the integration of new technologies in SEZs and development hubs can influence regional growth. This includes the impact of digital innovations, cleaner production technologies and digital value chains on developing areas.

Conclusions

References

- Krugman, P. Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. Journal of Political Economy 1991, 99, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, A. J. Equilibrium Locations of Vertically Related Industries. International Economic Review 1996, 37, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Krugman, P.; Venables, A.J. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade; MIT Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Farole, T.; Akinci, G. Special Economic Zones: Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions; World Bank, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.Z. Building engines for growth and competitiveness in China: The experience of special economic zones and industrial clusters; World Bank, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G.; Fernandez-Stark, K. Global value chain analysis: a guide, 2nd edition. 2016. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10161/12488.

- Borensztein, E.; De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics 1998, 45, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B.S. Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review 2004, 94, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNIDO. Guidelines for the design and implementation of special economic zones; United Nations Industrial Development Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, M.; Sato, M.; Yamagata, T. Spatial analysis of the location of Special Economic Zones in Asia: an econometric approach. Asian Economic Policy Review 2012, 7, 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Jha, S.; Verma, R. Sustainable supply chain management: A comprehensive framework and future research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 108, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of multinational enterprise activity. International Business Review. 2000.

- Pistorius, T.; Dufresne, M. Governance of special economic zones in Africa: Policy challenges and opportunities; World Bank Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, J. Economic zones in Africa: Lessons from Gabon's forestry sector. Journal of African Development Studies. 2015.

- Sunderland, T.; Ndoye, O. Forest resources and governance in Africa; CIFOR (Center for International Forestry Research), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, G. The effect of trade on the demand for skills: Evidence from the Labor Market. Review of Economics and Statistics 2008, 90, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G.; Puga, D. Micro-foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Henderson, J.V., Thisse, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2063–2117. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Clare, A. The Division of Labor and Economic Development. Journal of Development Economics 1996, 50, 15–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomström, M.; Kokko, A. Multinational corporations and spillovers. Journal of Economic Surveys 1998, 12, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, L.E.; Ndulu, B.J. Assessing the development impact of special economic zones in sub-Saharan Africa. African Development Review 2011, 23, 449–462. [Google Scholar]

- Lall, S.; Mengistae, T. Special Economic Zones in Africa: Comparative Insights from East Asia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3184. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farole, Thomas. Special economic zones in Africa: comparing performance and learning from global experience (anglais). Directions in development|trade Washington, DC: Banque mondiale. 2011. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/996871468008466349.

- Nickel, S. Deviations in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrics 1981, 49, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J.; Kripfganz, S.; Hayakawa, K. Offset correction method for moment estimator of dynamic panel data model. Econometrics and Statistics: The Future. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaene, G.; Jochmans, K. Likelihood reasoning in autoregression with fixed effects. Econometric Theory 2016, 32, 1178–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bun, M.J.G.; Carree, M.A. Bias correction estimation in dynamic panel data model. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 2005, 23, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, S. Quasi-maximum likelihood estimation of linear dynamic short-T panel data models. Stata Journal 2016, 16, 1013–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, S. A general method for estimating the moments of a linear dynamic panel data model. Proceedings of the STATA 2019 London conference: applying the employment equation. Economic Research Review 2019, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmann, A.O. Economic development strategy; Yale University Press: New Haven, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Perroux, F. Note sur la notion de "pôle de croissance". Économie appliquée 1955, 8, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein-Rodan, "The International Development of Economically Disadvantaged Regions", International Affairs v 20 (1944) #2 (avril), pp. 157-65.

- Milton, S. Sous-développement et pôles de croissance économique et sociale. Persée In : Tiers-Monde 1974, 15, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal, G. Economic theory and underdeveloped regions; Duckworth: London, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 107–140. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, R.P. Regional planning and national development, édition Goodreads; Vikas Publishing: New Delhi, Inde, 1978; ISBN 10: 0706905555 / ISBN 13: 9780706905557. [Google Scholar]

| Authors & Studies | Econometric approach | Main results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krugman (1991) - "Increasing Returns and Economic Geography" (rising yields and economic geography) | Theoretical model with increasing returns and economies of scale | Agglomeration creates increasing returns, reducing production costs and encouraging innovation, leading to differences in growth between regions. | Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. Journal of Political Economy. |

| Venables (1996) - "Equilibrium Locations of Vertically Related Industries". | Spatial competition model integrating transport costs and agglomeration effects | Agglomeration economies increase international competitiveness, reduce intermediation costs and stimulate exports. | Venables, A. J. (1996). Equilibrium Locations of Vertically Related Industries. International Economic Review. |

| Fujita, Krugman, Venables (1999) - "Spatial economics: Cities, regions and international trade". | Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model | Agglomeration boosts productivity, improves international competitiveness and helps developing countries overcome barriers to exports. | Fujita, M., Krugman, P., & Venables, A. J. (1999). The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade. MIT Press. |

| Michaels (2008) - "The Effect of Trade on the Demand for Skill". | Panel regressions | Industrial agglomerations foster innovation, increase exports and attract foreign investment. | Michaels, G. (2008). The Effect of Trade on the Demand for Skill. Review of Economics and Statistics. |

| Duranton & Puga (2004) - "Micro-foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies". | Spatial modeling and panel data analysis | Agglomeration boosts productivity, innovation and specialization, providing a favorable environment for industrial investment and export growth. | Duranton, G. and Puga, D. (2004). Micro-foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics. |

| Rodríguez-Clare (1996) - "The division of labor and economic development". | Theoretical model with panel data | Agglomeration economies enable greater specialization, stimulating exports and attracting foreign direct investment. | Rodríguez-Clare, A. (1996). The Division of Labor and Economic Development. Journal of Development Economics. |

| Approach | Description |

|---|---|

| Panel regressions | Analysis of long-term effects, controlling for differences between countries and periods. |

| Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models | Simulation of the impact of agglomeration policies on the overall economy, including exports and growth. |

| Endogenous growth models | Integration of agglomerations to study their influence on innovation, productivity and exports. |

| Difference-in-difference (DiD) methods | Evaluate the effects of public policies by comparing regions before and after interventions. |

| Spatial models | Analysis of the transnational effects of conurbations, taking into account the interconnections between regions. |

| Impact | Details |

|---|---|

| Industrial growth | Agglomeration promotes growth by improving productivity, specialization and innovation. |

| Investment | Attract foreign direct investment (FDI) by reducing production costs and facilitating access to industrial networks. |

| Exports | Increase exports through economies of scale and improved competitiveness. |

| Regional disparities | Agglomeration can increase inequality if benefits are concentrated in certain regions. |

| Variables | Units | Descriptions | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nomber of Companies | Number of businesses: Number of businesses in the areas studied. | Source 1: Dashboard of the Gabonese economy (Link: http://www.dgepf.ga/23-publications/25-tableau-de-bord-de-l-economie/169-tableau-de-bord-de-l-economie/). | |

|

FDI+PI_T USD (Foreign direct investment + Total public investment) |

Millions of dollars (USD) | (Foreign direct investment (FDI) plus total public investment in the construction, management and development of the Nkok SEZ). Rated: FDI+PI_TUSD. |

Source 2: EY and Mays Mouissi Consulting (2023) (Link: https://www.mays-mouissi.com/?utm). |

|

Exp_T USD (Export income) |

Millions of dollars (USD) | Total exports, in millions of dollars, represent Gabon's export earnings from wood products. Noted : Exp_T USD. |

Source 3 : FAOSTAT (Link : https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FO). |

|

Ind_P_TUSD (Industrial income) |

Millions of dollars (USD) | Total industrial production by value (million USD), represents the sum total of industrial revenues from companies in the timber forestry sector in Gabon. Rated : Ind_P_TUSD. | Source 3: FAOSTAT (Link : https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FO). |

| (1) | (2) | |

| VARIABLES | In the Nkok SEZ (homogeneous space) | Out Nkok SEZ (heterogeneous space) |

| Dependant Variable (Nomber of Companies) | ||

| LogExp_TUSD | 0.410*** | 0.132* |

| (0.001) | (0.062) | |

| LogInd_P_TUSD | 0.730*** | 0.157*** |

| (0.001) | (0.010) | |

| Constant | 1.016*** | 0.440 |

| (0.005) | (0.407) | |

| Comments (N) | 12 | 12 |

| R-squared | 0.999 | 0.986 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Independent variables | In SEZ of Nkok | Out SEZ of Nkok | Macroenvironment |

| Dependent variable (LogFDI_PI_TUSD) | |||

| L.LogFDI_PI_TUSD | 0.093*** | -0.276*** | -0.262*** |

| (0.019) | (0.088) | (0.078) | |

| Nomber of Companies | 2.350*** | 1.106*** | 1.576*** |

| (0.772) | (0.189) | (0.427) | |

| LogExp_TUSD | -0.114 | -0.115*** | -0.045 |

| (0.086) | (0.041) | (0.055) | |

| LogInd_P_TUSD | -0.243*** | -0.249*** | -0.244*** |

| (0.030) | (0.003) | (0.037) | |

| Constant | -0.164 | 2.197*** | 0.757 |

| (1.025) | (0.528) | (0.655) | |

| Autocorrelation order 1 | -1.4138 (0.1574) | -1.4135 (0.1575) | -1.7239 (0.1247) |

| Autocorrelation order 2 | 0.9171 (0.3591) | -1.1573 (0.2471) | -1.2262 (0.2201) |

| (N/T) | 2/16 | 2/16 | 3/24 |

| Phase / Scenario | Strategic criteria | Reinforcement Tools and Models | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 0: Start-up requirements | Public and private initiatives | SWOT analysis | Identify opportunities and threats to better guide decisions. |

| Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) | SEZ Strategic Planning Methods | Involvement of local and international players for balanced alliances. | |

| Attractive tax and customs framework | SEZ profitability assessment models (UNIDO, 2009) | Assessing the economic, social and environmental impact of tax exemptions. | |

| Appropriate regulatory framework | Performance Scorecards (PSC) | Monitoring the regulatory stability and attractiveness of SEZs. | |

| Simplified administrative procedures | SWOT analysis | Identification of bureaucratic obstacles and optimization solutions. | |

| Strategic planning | SEZ Strategic Planning Methods | Integration of a participative and interactive governance model. | |

| Strategic market intelligence | Simulations and Modeling of Economic Impacts | Forecasts of economic and industrial trends. | |

| Strategic infrastructure | Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Mapping of existing infrastructures and identification of strategic locations. | |

| Power industries | Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) models | Evaluation of priority industries to maximize return on investment. | |

| Secondary industries | SEZ profitability assessment models | Value chain analysis and support for complementary industries. | |

| Propelled businesses and industries | Strategic Planning & SWOT | Organization of upstream and downstream value chains. | |

| Strategic location | Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Better spatial management of development hubs. | |

| Innovation system | SEZ Strategic Planning Methods | Strategy for capturing and managing technological innovation. | |

| Collaborative framework between stakeholders | Performance Scorecards (PSC) | Monitoring interactions between governments, companies and research institutions. | |

| Cognitive system (R&D, incubators, universities, laboratories) | Performance Scorecards (PSC) | Monitoring R&D initiatives and the impact of incubators and universities. | |

| Satisfactory social policies | SWOT analysis | Reducing inequalities and improving working conditions. | |

| Satisfactory corporate policies | Performance Scorecards (PSC) | Monitoring social inclusion and participation of local populations. | |

| Phase 1 : Acceleration | Scenario 1 : Lethal | SWOT & CBA analysis | Identify causes of failure and make strategic adjustments. |

| Scenario 2 : Stagnation | Performance scorecards (PSC), CBA | Assessment of investment and infrastructure delays. | |

| Scenario 3 : Acceleration and diversification | Economic Impact Simulations & Modeling | Industry expansion forecasts and economic impact. | |

| Phase 2 : Transition to equilibrium | Scenario 1 : Depolarization | Performance Dashboards, Profitability Evaluation Models | Monitoring the impact of company departures and readjusting policies. |

| Scenario 2 : Transition to equilibrium | Strategic Planning, GIS, Economic Impact Modeling | Monitoring industrial diversification and economic stabilization. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).