1. Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium contained 272 species and 24 validly published subspecies [

1]. Mycobacteria from

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC) such as

M. bovis,

M. caprae or

M. tuberculosis, are the best known due to their effects on human and animal health [

2]. On the other hand, within the genus Mycobacterium, all mycobacteria other than MTC,

M. leprae and

M. ulcerans are called non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) or atypical mycobacteria.

The NTM group includes more than 150 different species, with the

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) being the most well-known due to its ability to cause opportunistic infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals [

3]. NTM are generally believed to be acquired from the environment through ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact, resulting in lymphadenitis, pulmonary and disseminated infections, and skin and soft tissue infections [

4]. Most of them are widely distributed in the environment, being present in soil, water, dust, in living organisms or even food [

5], although the natural reservoir of some species such as

M. kansasii and

M. xenopi remain unknown [

6].

These kinds of infections caused by the NTM are emerging in the western world due to several factors like an increase of mycobacterial infection sources in the environment or the improvements in laboratoy detection techniques [

4].

In veterinary medicine, except for

M. avium subsp.

paratuberculosis, the presence of NTM is generally not specifically investigated [

7]. Thus, isolation of NTM is usually a secondary finding of MTC research, since active surveillance for the detection of NTM is not contemplated in livestock health control campaigns and wildlife surveillance programs in general [

2].

In fact, there are few studies identifying NTM in wildlife in Extremadura, a region located in south-western Spain. The first reported identifications were

M. fortuitum in black kite (

Milvus migrans) and

M. avium in wild boar (

Sus scrofa) [

8]. In Spain, other NTM have been identified as

M. avium subsp.

avium and

M. avium subsp.

hominissuis, which have been detected in badger (

Meles meles) and wild boar [

9,

10],

M. chelonae, M

. intracellulare and

M. avium, in wildboar from Extremadura [

11]; and

M. intracellulare and

M. interjectum which were found in red deer (

Cervus elaphus) [

12]. Members of MAC have been reported as well in roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus) and foxes (

Vulpes vulpes) [

10].

However, NTM have not been reported in other wildlife species like the Iberian Lynx (

Lynx pardinus). Regarding TB, a first case in free-living Iberian Lynx from Doñana National Park in Spain was published by Briones et al., in 2001 and there is some more description about MTC isolates in lynx. In fact, according to Visavet database

M. bovis has been isolated from 7 lynxes from 1999 to 2022 spolygotyped as SB1232 (n=3), SB0295 (n=2), SB1258 (n=1) from Huelva, in Andalusia Region and SB1263 (n=1) from Toledo, in Castilla-La Mancha Region (

www.visavet.es/mycodb). However, no studies have been done to determine its health impact.

The population of Iberian Lynx, a species that 20 years ago was categorized as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and considered as lost by many experts, is growing today. One of the main concerns about Iberian Lynx repopulation is to avoid sanitary problems caused by infectious and parasitary pathogens that may lead to mortality in this species. Viral infections such as parvovirus, canine distemper virus (CDV), feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and Aujeszky's disease (SuHV-1) that could be fatal in the Iberian lynx, were analyzed in 2021 and the results indicated that infectious diseases did not pose a threat to the constant growth of the Iberian lynx population in this region [

13]. In fact, in the Doñana National Park (southern Spain) there was a documented serious FeLV epidemic in 2006 that caused a high mortality rate in Iberian lynxes [

14]. In this sense MTC and NTM are also pathogens that could play an important role, since Iberian Lynx is known to predate mainly on rabbits and occasionally on wild ungulates, both involved in the propagation cycle of both MTC and NTM [

15].

The objective of the current study was to analyze and identify the presence of mycobacteria in the Iberian Lynx population to know if, at present, the risks of TB and other mycobacteriosis can be ruled out in this species. In addition, it is intended to assess the effects of the presence of mycobacteria on the health of lynxes, to know its impact on the reintroduction of this animal species in nature.

2. Materials and Methods

Of the total of 64 lynxes born in captivity analyzed in this study, 59 were captured alive and five of them were road-killed. The samples came from individuals recaptured in the livestock areas of southern Badajoz, while only nine lynxes were captured in the province of Cáceres (northern Extremadura) (

Table 1). These samples were analyzed by veterinarians from FOTEX S.L., GPEX and the UEX-Mycobacteria and Brucellae Laboratory (Animal Health Department, School of Veterinary Sciences, University of Extremadura, Cáceres, Extremadura, Spain).

Free-ranging lynxes were captured using commercial cage traps (Tomahawk models 108 and 207, Tomahawk Live Trap Co., Tomahawk, Hazelhurst, WI, USA) baited with rabbits. Once captured, they were anesthetized using a mixture of dexmedetomidine-midazolam-ketamine. Anesthetized Iberian lynxes underwent a complete routine health evaluation. Blood (1–3 mL) was obtained from saphenous vein and collected in EDTA-coated tubes and/or serum separator tubes (Aquisel, Selecta Group, Barcelona, Spain). Lynxes were identified by microchip reading and spot pattern. The lynxes found dead were subjected to a field postmortem examination, but no hematological or blood biochemical analyses could be performed. In addition, data could not be taken from two of them due to the state of decomposition of their corpses.

The samples of choice to analyze mycobacteria were tracheal swabs and tracheobronchial washings from the live-captured lynxes as well as mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from the two road-killed lynxes. All samples and data were taken by veterinarians from FOTEX S.L. and GPEX and the studies described in this paper were carried out by the UEX-Mycobacteria and Brucellae Laboratory.

Whenever possible, epidemiological information about each individual animal was recorded, including age (yearlings: < 1 year old; subadults: 1 to 3 years old; adults: 3 to 10 years old), sex, physical exploitation/body condition, georeferenced location, and other parameters like lymph node palpation to determinate lymphadenomegaly.

Real-Time PCR

The cotton head of each nasopharyngeal swab was rehydrated in 1,5ml of distilled water, vortexed for a few seconds and subsequently left to rest for 15 minutes. 1ml of suspension was used for culture and the other 0,5ml was used for qPCR.

Regarding tracheobronchial washings, 4 ml were used, 2 for qPCR and 2 for culture.

Suspensions were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 13,000 rpm. In the case of tracheobronchial lavages, the supernatant was discarded, and a swab was inserted in the sediment which was then used to extract the DNA with the kit.

Lymph nodes were homogenized with distilled water in a stomacher for 4 minutes. Then, for the extraction of DNA from all the samples, we followed the manufacturer's protocol of Patho gene-spinTM Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, South Korea).

To determine the presence of TB DNA, a specific real-time PCR assay targeting the IS1561’ locus was carried out using a pair of primers IS1561-F (5’ GATCCAGGCCGAGAGAATCTG 3’) and IS1561-R (5’ GGACAAAAGCTTCGCCAAAA 3’) and a IS1561-Probe (5’ ACGGCGTTGATCCGATTCCGC 3’) (Eurogentec, Belgium) [

16] with an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 thermal-cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). IS1561’ locus sequence is used as is present in all the MTC members except in

M. microti [

17]. A strain of

M. bovis (SB0121) was used as a positive control and non-template samples were used as negative controls.

Mycobacteria Culture

For the mycobacteria cultivation from nasopharyngeal swabs, the steps were as follows: 1ml was subjected to a treatment with bovine serum albumin for 3 minutes to enhance the mycobacteria growth, a decontamination treatment with N-acetyl-L-cysteine-sodium hydroxide solution (BBL MycoPrep, BD) for 15 minutes and with di-Sodium Hydrogen Phosphate anhydrous (Panreac) like a stop solution. Then, 0.5ml were cultured in liquid media (BD BBL MGIT, Becton and Dickinson, USA), because MGIT has a higher sensitivity for growth detection and offers faster results compared with solid media cultures. Culture media were incubated using a BACTEC MGIT 960 semi-automatic culture incubator (Becton and Dickinson, USA) for 42 days.

After centrifugation of the tracheobronchial lavage samples, we obtained 1 ml of the sediment, which was cultured following the same steps described in the previous section.

Regarding lymph nodes, 7,5ml of the homogenate was mixed with 7,5ml of the same decontaminant and 35ml of stop solution. The samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and 0.5ml of the pellet was inoculated in the same liquid culture.

Mycobacterial Isolation and DNA Extraction

DNA extraction for mycobacterial identification was performed by taking bacterial growth from the liquid medium. For this purpose, 1.5 ml of the culture medium were collected in an Eppendorf vial and centrifuged for 30 seconds. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 250 µl of ultrapure water. The suspensions were inactivated at 100 ºC for 10 min and centrifuged to clean the DNA in the supernatant.

Mycobacterium spp. Identification by Convencional PCR

Conventional PCR to identify genus Mycobacterium and MTC was carried out following standard methods [

18] using the primers TB1-F (5’ GAACAATCCGGAGTTGACAA 3’), TB1-R (5’ AGCACGCTGTCAATCATGTA 3’), MYCGEN-F (5’ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTGGCTCAG 3’) and MYCGEN-R (5’ TGCACACACAGGCCACAAGGGA 3’) (Eurogentec, Belgium) [

19], the polymerase DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, USA) and the DNAs previously obtained. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 amplification cycles including 30 seconds of denaturation at 95°C, 1 min of annealing at 60°C and 2 min of primer extension at 72°C; and finally, an elongation step of 10 min at 72°C.

The products were analysed by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel (Condalab, España). The presence of a unique 1030 base pairs (bp) electrophoretic band indicated species of NTM and two DNA fragments at 1030 bp and 370 bp corresponded to MTC.

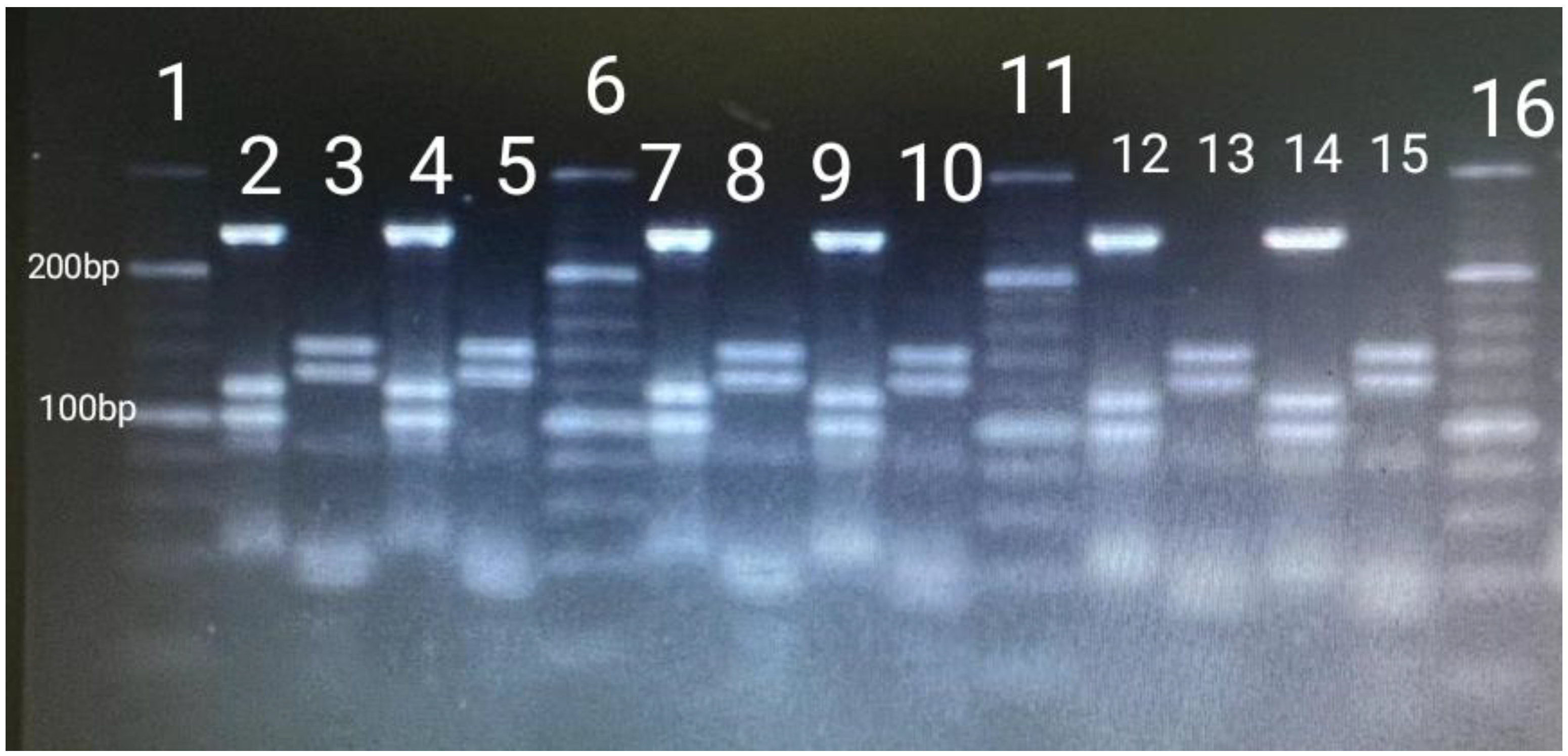

NTM Identification by PCR and Restriction Enzyme Analysis and Interpretation (PRA-hsp65)

To identify the different species of NTM isolated, a fragment (441-bp) of the 65-kDa heat shock protein gene (hsp65) was amplified by two specific primers Tb11 (5’ ACCAACGATGGTGTGTCCAT 3′) and Tb12 (5′ CTTGTCGAACCGCATACCCT 3′) (Eurogentec, Belgium) [

20]. The PCR conditions were as follow: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 45 amplification cycles including 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 60°C and 1 min of primer extension at 72°C; and an elongation step of 10 min at 72°C [

11,

20].

The hsp65 fragment was digested with BstEII and HaeIII (Takara Biotechnology Inc., Dalian, Japan) restriction enzymes. The digestion was carried out in accordance with the article published by Telenti et al., in 1993. The fragments obtained were detected in a 3% agarose gel (Condalab, España) and compared with a 20-500 bp molecular weight marker (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Results were interpreted with the help of an algorithm described by Chimara et al., in 2008 [

21]. To avoid confusion with primer and primer-dimer bands, restriction fragments shorter than 50bp were disregarded.

Blood Analysis

The Life Lynxconnect project carried out blood tests. A 5-population automatic blood analyzer (ProCyte DX, IDEXX®) was used to hematology, in which the following parameters were analyzed: total red blood cell count (RBC), hematocrit value, hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), total and differential leukocyte count (WBC), and platelet count. In addition, blood smears were taken for morphological study of blood cells, observed by light microscopy (x40 and x100; Diff-Quick staining method, QCA Laboratory).

Plasma biochemistry was performed in an automatic blood biochemistry analyzer (Spin200E, Spinreact®), using specific commercial kits from Spinreact® Laboratories. Plasma concentrations of glucose, total protein, albumin, urea, creatinine, calcium, phosphorus, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT/GPT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST/GOT), cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in all patients. The albumin/globulin ratio was subsequently calculated. Plasma concentrations of sodium, potassium and chloride were determined by automatic electrolyte analyzer (EasyElectrolytes Medicat®).

Plasma electrophoresis was carried out in cellulose acetate, using a commercial kit for plasma proteins (Seleo Engineering®) in an automated equipment (Selvet 24®). Buffer solution (pH 8.8), staining solution (Ponceau red) and decolorizing solution (citric acid, sodium phosphate and sodium azide), provided by the kit manufacturer, were used. Protein migration was performed at 10 mA for 12 minutes. The electrophoresis result was expressed in g/dl.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software. Associations between the presence of mycobacteria and cualitative variables (age, sex, and presence of lymphadenomegaly) were analysed using Pearson's chi-square test while the association between the presence of mycobacteria and body condition (quantitative variable) were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Firstly, the Shapiro Wilk normality test (n<50) was performed to assess if the blood parameters followed a normal distribution. Then, to know if there were significant differences in the blood parameters according to the presence of mycobacteria, the T-student test was performed for those parameters with normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney U-test for those with non-normal distribution. Those comparations with p < .05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All the samples analyzed resulted negative for MTC identification by real-time PCR. Regarding the cultures, 48,44% of cultures (n=31) had growth and were analyzed following conventional PCRs to identify genus Mycobacterium and MTC. After that, it was observerd that no sample had positive results for MTC but a total of 87,09% (n=27) of isolates were identified as belonging to the genus (NTM).

After comparing our restriction fragments patterns with the PRA- hsp65 patterning algorithm described by Chimara et al. (2008) it was noted that the most frequently identified mycobacterium was

M. lentiflavum with a 77,78% (n=21) of the total (

Figure 1), followed by

M. gordonae identified in only 4 cultures. Lastly, in two of the cultures no mycobacteria could be identified, which could be due to contamination.

No association was detected between the detection of NTM and age group/class (p=0,893), sex (p=0,264), body condition (p=0,843) or existence of lymphadenomegaly (p=0,075) to even though enlarged lymph nodes were observed in 5 lynxes, M. lentiflavum being detected in three of them and M. gordonae in one of them.

On the other hand, the effect of the presence of mycobacteria on the hematology and blood biochemistry of all lynxes captured alive was studied (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this study, no MTC mycobacteria were identified in the lynxes analyzed, despite Extremadura is an area of Spain where TB has been described in cattle and wildlife, which may suggest that the lynx has little interaction with these animals, perhaps due to its solitary nature [

22]. Furthermore, MTC mycobacteria infections in lynxes may be rare, as, since 2002 to date, it has been identified only in one lynx in the province of Toledo (central Spain) (

https://www.visavet.es/mycodb). Nevertheless, this may be also due to the fact that there are few studies of TB in Iberian lynx populations. However, the information gained in this study is novel as the presence of NTM in the Iberian Lynx population, although expectable as ubiquitous bacteria, has not been described so far. Our findings indicate that

M. lentiflavum, characterized by slow growth of tiny yellow colonies [

23], is a common mycobacterium in the lynx population from the studied area. As with other NTM,

M. lentiflavum has been isolated from soil and water samples around the world [

24] and even from raw buffalo milk [

25]. On the other hand,

M. gordonae has been largely isolated from water resources, because it has few nutrition requirements and a high resistance and tolerance against chlorine [

26]. These findings suggest that water can be a source of infection of both mycobacteria for animals and people. In fact, in the Serengeti ecosystem, Tanzania, where humans and animals live closely together and many areas lack safe drinking water,

M. lentiflavum has been isolated from 6 samples from cattle, 3 from buffalo specimens, 1 from Thompson gazelle and 1 isolate from a warthog [

27].

M. lentiflavum was considered in 2016 among the new species of recently described NTM, and few cases had been published to that date after the first description of the infection in 1997 [

28]. Nevertheless, unlike

M. gordonae, a species of low pathogenicity which rarely causes disease in humans [

29],

M. lentiflavum is an NTM that causes infectious diseases of humans, such as cervical lymphadenitis, lung disease, and disseminated infections [

30,

31]. In fact, this mycobacterium has also been isolated from tracheobronchial lavage specimens in humans [

32]. These results point to tracheobronchial lavages as samples of choice for the detection of mycobacteria. Lymphadenomegaly has been repeatedly observed in humans infected by this pathogen [

33] especially in young children [

31,

34]. It agrees with our results, since in four of the five lynxes that presented lymphadenomegaly it was associated with NTM infections.

In addition to affecting humans, this mycobacterium has been recently isolated from red deer, roe deer and wild boar, most of which had tuberculous lesions in retropharyngeal nodes [

2]. However, unlike the Iberian lynx, several different NTM have been isolated from these species, being

M. avium subsp.

avium and

M. avium subsp.

hominissuis from MAC,

M. nonchromogenicum from the

M. terrae complex,

M. lentiflavum from the

M. simiae complex and

M. chelonae the species most frequently isolated [

2,

11]. The difference between finding almost exclusively

M. lentiflavum in lynxes in our study and the diversity of NTM found in other wild hosts may be related to their behavior. Wild boar, red deer or roe deer habits imply a very close interaction between them as they share mud, water and food areas with each other and with cattle, thus favouring the transmission of contagious agents such as NTM between them. Behavioural patterns of wild boar such as rooting and wallowing during rut also exemplify this interaction [

35,

36]. However, lynxes lack wallow or rooting habits, being generally solitary animals, distributed throughout the territory according to sex (with males occupying larger territories than females), the abundance of rabbits and the quality of the habitat. 94% of the Iberian lynx's diet is based on wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) [

22], although they can also feed other preys as red-legged partridges (

Alectoris rufa), hares (

Lepus granatensis), different species of birds, rodents and, on rare occasions, carrion. Furthermore, while

M. gordonae has been described in small mammals [

37,

38],

M. lentiflavum has not been described in rabbits, partridges or mice so we cannot affirm that these animals would be a source of infection for the Lynx. On the other hand, all samples in this study were taken from the upper respiratory tract of live animals (except 2 lymph nodes) while in the previously mentioned studies on NMT in wild boar and red deer a much greater larger number of samples were taken mainly from lymph nodes or organs with TB like lesions belonging to hunted animals. This difference in the kind and number of samples would also explain the variety of NTM identified in game animals and the low variety of NTM identified in the lynx. Interestingly,

M. lentiflavum has also been identified in samples from tracheobronchial washings in humans as mentioned before, so it could be an usual opportunistic mycobacterium of the upper respiratory tract. Finally, the absence of significant differences both in blood parameters and body condition status between healthy and mycobacterium-carrier lynxes as well as the occurrence of lymphadenomegaly in only 4 lynxes show that the presence of these two mycobacteria

(M. lentiflavum and

M. gordonae) seem not to be detrimental to the health of lynxes.

5. Conclusions

Although no MTC has been isolated from the analyzed lynx population, it has been observed that they are a reservoir of environmental NTM, mainly M. lentiflavum, the most isolated species. However, the absence of significant differences in both blood parameters and body condition status of healthy and mycobacteria-positive lynxes demonstrates that the presence of these two mycobacteria (M. lentiflavum and M. gordonae) seems not to be detrimental to the lynx health.

Author Contributions

The contributions of the different authors were: conceptualization, NJP, BS, JP and MGM; Methodology, NJP, BS, JP, MGM and RB.; Software, NJP, DR and MGM.; Validation, NJP, BS, JP, RB, MGM and DR.; Formal Analysis, NJP, JHM and DR; Investigation, NJP, BS, JP and MGM.; Resources, JHM and RB.; Data Curation, DR and JHM; Writing-original draft, NJP.; Writing – Review & Editing BS, JP, RB, MGM, DR and JHM.; Visualization, NJP, BS, JP, RB, MGM and DR.; Supervision, JHM and DR.; Funding Acquisition, JP and JHM.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by ‘Dirección General de Sostenibilidad, Servicio de Conservación de la Naturaleza’ and ‘Servicio de Sanidad Animal’ (ref:274/21), Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Sostenible, Junta de Extremadura.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NTM |

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| MAC |

M. avium complex |

| HSP65 |

65-kDa Heat Shock Protein Gene |

| CDV |

Canine Distemper Virus |

| SuHV-1 |

Aujeszky's Disease |

| FeLV |

Feline Leukaemia Virus |

| RBC |

Red Blood Cell |

| MCV |

Mean Corpuscular Volume |

| MCHC |

Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration |

| WBC |

Differential Leukocyte Count |

| ALT/GPT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST/GOT |

Aspartate Aminotransferase |

References

- Parte AC, Carbasse JS, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M. List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70(11):5607–12. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Castro L, Barral M, Arnal MC, Fernández de Luco D, Gortázar C, Garrido JM, et al. Beyond tuberculosis: Diversity and implications of non-tuberculous mycobacteria at the wildlife–livestock interface. Transbound Emerg Dis [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Feb 8];69(5):e2978–93. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tbed.14649.

- Sweeney RW, Collins MT, Koets AP, Mcguirk SM, Roussel AJ. Paratuberculosis (Johne’s Disease) in Cattle and Other Susceptible Species. J Vet Intern Med [Internet]. 2012 Nov [cited 2021 Mar 1];26(6):1239–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23106497/. [CrossRef]

- Nishiuchi Y, Iwamoto T, Maruyama F. Infection sources of a common non-tuberculous mycobacterial pathogen, Mycobacterium avium complex [Internet]. Vol. 4, Frontiers in Medicine. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2017 [cited 2021 Mar 1]. p. 27. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5339636/. [CrossRef]

- Jagielski T, Minias A, van Ingen J, Rastogi N, Brzostek A, Żaczek A, et al. Methodological and clinical aspects of the molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2016 Feb 24 [cited 2021 Mar 1];29(2):239–90. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4786889/. [CrossRef]

- Forbes BA, Hall GS, Miller MB, Novak SM, Rowlinson MC, Salfinger M, et al. Practice guidelines for clinical microbiology laboratories: Mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2021 Mar 1];31(2). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5967691/. [CrossRef]

- Biet F, Boschiroli ML. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of veterinary relevance. Res Vet Sci. 2014;97(S):S69–77. [CrossRef]

- Tato Jiménez, Á (1999). Infecciones por Mycobacterium spp. en animales salvajes en la provincia de Cáceres. Thesis. Universidad de Extremadura.

- Balseiro A, Merediz I, Sevilla IA, García-Castro C, Gortázar C, Prieto JM, et al. Infection of Eurasian badgers (Meles meles) with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) bacteria. Vet J. 2011 May 1;188(2):231–3. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Mendoza M, Marreros N, Boadella M, Gortázar C, Menéndez S, de Juan L, et al. Wild boar tuberculosis in Iberian Atlantic Spain: A different picture from Mediterranean habitats. BMC Vet Res [Internet]. 2013 Sep 8 [cited 2021 Mar 1];9:176. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3844463/. [CrossRef]

- García-Jiménez WL, Benítez-Medina JM, Martínez R, Carranza J, Cerrato R, García-Sánchez A, et al. Non-tuberculous Mycobacteria in Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) from Southern Spain: Epidemiological, Clinical and Diagnostic Concerns. Transbound Emerg Dis [Internet]. 2015 Feb 1 [cited 2021 Feb 25];62(1):72–80. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/tbed.12083. [CrossRef]

- Gortazar C, Torres MJ, Acevedo P, Aznar J, Negro JJ, De La Fuente J, et al. Fine-tuning the space, time, and host distribution of mycobacteria in wildlife. BMC Microbiol [Internet]. 2011 Feb 2 [cited 2023 Feb 8];11(1):1–16. Available from: https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2180-11-27. [CrossRef]

- Nájera F, Grande-gómez R, Peña J, Vázquez A, Palacios MJ, Rueda C, et al. Disease Surveillance during the Reintroduction of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus) in Southwestern Spain. Anim an Open Access J from MDPI [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Oct 25];11(2):1–19. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7923217/.

- Luaces I, Doménech A, García-Montijano M, Collado VM, Sánchez C, Tejerizo JG, et al. Detection of Feline leukemia virus in the endangered Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus). J Vet Diagnostic Investig [Internet]. 2008 May 1 [cited 2023 Dec 22];20(3):381–5. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/104063870802000325?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed.

- Gortázar C, Torres MJ, Vicente J, Acevedo P, Reglero M, de la Fuente J, et al. Bovine Tuberculosis in Doñana Biosphere Reserve: The Role of Wild Ungulates as Disease Reservoirs in the Last Iberian Lynx Strongholds. PLoS One [Internet]. 2008 Jul 23 [cited 2023 Feb 10];3(7):e2776. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0002776.

- Riojas MA, McGough KJ, Rider-Riojas CJ, Rastogi N, Hazbón MH. Phylogenomic analysis of the species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex demonstrates that Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium caprae, Mycobacterium microti and Mycobacterium pinnipedii are later heterotypic synonyms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Oct 25];68(1):324–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29205127/. [CrossRef]

- Barbier E, Boschiroli ML, Gueneau E, Rochelet M, Payne A, de Cruz K, et al. First molecular detection of Mycobacterium bovis in environmental samples from a French region with endemic bovine tuberculosis. J Appl Microbiol [Internet]. 2016 May 1 [cited 2023 Feb 9];120(5):1193–207. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jam.13090. [CrossRef]

- Liébana E, Aranaz A, Francis B, Cousins D. Assessment of genetic markers for species differentiation within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2021 Jul 15];34(4):933. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC228920/?report=abstract. [CrossRef]

- Cousins D V., Wilton SD, Francis BR. Use of DNA amplification for the rapid identification of Mycobacterium bovis. Vet Microbiol. 1991 Apr 1;27(2):187–95. [CrossRef]

- Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger EC, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2021 Feb 25];31(2):175–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8381805/. [CrossRef]

- Chimara E, Ferrazoli L, Ueky SYM, Martins MC, Durham AM, Arbeit RD, et al. Reliable identification of mycobacterial species by PCR-restriction enzyme analysis (PRA)-hsp65 in a reference laboratory and elaboration of a sequence-based extended algorithm of PRA-hsp65 patterns. BMC Microbiol [Internet]. 2008 Mar 20 [cited 2021 Feb 25];8(1):48. Available from: http://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2180-8-48. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Sánchez JM, Ballesteros-Duperón E, Bueno-Segura JF. Feeding ecology of the Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus in eastern Sierra Morena (Southern Spain). Acta Theriol (Warsz) [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2023 Feb 22];51(1):85–90. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03192659. [CrossRef]

- Tortoli E. Impact of genotypic studies on mycobacterial taxonomy: The new mycobacteria of the 1990s. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2003 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Feb 16];16(2):319–54. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/CMR.16.2.319-354.2003. [CrossRef]

- Marshall HM, Carter R, Torbey MJ, Minion S, Tolson C, Sidjabat HE, et al. Mycobacterium lentiflavum in Drinking Water Supplies, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011 Mar [cited 2023 Feb 16];17(3):395. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3165988/.

- Jordão Junior CM, Lopes FCM, David S, Farache Filho A, Leite CQF. Detection of nontuberculous mycobacteria from water buffalo raw milk in Brazil. Food Microbiol. 2009 Sep 1;26(6):658–61.

- Arfaatabar M, Karami P, Khaledi A. An update on prevalence of slow-growing mycobacteria and rapid-growing mycobacteria retrieved from hospital water sources in Iran – a systematic review. Germs [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Feb 16];11(1):97. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8057855/. [CrossRef]

- Katale BZ, Mbugi E V., Botha L, Keyyu JD, Kendall S, Dockrell HM, et al. Species diversity of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from humans, livestock and wildlife in the Serengeti ecosystem, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Nov 18 [cited 2023 Feb 14];14(1):1–8. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-014-0616-y. [CrossRef]

- Del Olmo Izuzquiza IR, Cirac MLM, Alonso MB, Prades PB, Laleona CG. [Mycobacterium lentiflavum lymphadenitis: two case reports]. Arch Argent Pediatr [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Feb 16];114(5):e329–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27606656/.

- Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, Cambau E, Wallace RJ, Andrejak C, et al. Treatment of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease: AnOfficial ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline. Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Feb 14];56(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8375621/.

- Jarzembowski JA, Young MB. Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med [Internet]. 2008 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Feb 14];132(8):1333–41. Available from: https://meridian.allenpress.com/aplm/article/132/8/1333/460552/Nontuberculous-Mycobacterial-Infections.

- Miqueleiz-Zapatero A, Santa Olalla-Peralta C, Guerrero-Torres MD, Cardeñoso-Domingo L, Hernández-Milán B, Domingo-García D. Mycobacterium lentiflavum como causa principal de linfadenitis en población pediátrica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018 Dec 1;36(10):640–3. [CrossRef]

- Vise E, Mawlong M, Garg A, Sen A, Shakuntala I, Das S. Recovery of Mycobacterium lentiflavum from bronchial lavage during follow-up of an extrapulmonary tuberculosis patient. Int J Mycobacteriology [Internet]. 2017 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Feb 16];6(3):315. Available from: https://www.ijmyco.org/article.asp?issn=2212-5531;year=2017;volume=6;issue=3;spage=315;epage=317;aulast=Vise. [CrossRef]

- Piersimoni C, Goteri G, Nista D, Mariottini A, Mazzarelli G, Bornigia S. Mycobacterium lentiflavum as an Emerging Causative Agent of Cervical Lymphadenitis. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2004 Aug [cited 2023 Oct 27];42(8):3894. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC497572/. [CrossRef]

- Yagi K, Morimoto K, Ishii M, Namkoong H, Okamori S, Asakura T, et al. Clinical characteristics of pulmonary Mycobacterium lentiflavum disease in adult patients. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Oct 27];67:65–9. Available from: http://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201971217303132/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Anaya A, Herrero J, Rosell C, Couto S, García-Serrano A. Food habits of wild boars (Sus scrofa) in a Mediterranean coastal wetland. Wetlands. 2008 Mar;28(1):197–203. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llario P. The sexual function of wallowing in male wild boar (Sus scrofa). J Ethol. 2005 Jan;23(1):9–14. [CrossRef]

- Durnez L, Katakweba A, Sadiki H, Katholi CR, Kazwala RR, MacHang’U RR, et al. Mycobacteria in Terrestrial Small Mammals on Cattle Farms in Tanzania. Vet Med Int [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2023 May 19];2011. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3139188/. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Castro L, Torrontegi O, Sevilla IA, Barral M. Detection of Wood Mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) Carrying Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria Able to Infect Cattle and Interfere with the Diagnosis of Bovine Tuberculosis. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2023 May 19];8(3). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7143357/. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).