Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction and Literature Review

Methodology

System Description

Cost Function with Frobenius Output Measure

System Training and Training Pairs

Noise Simulation

Results

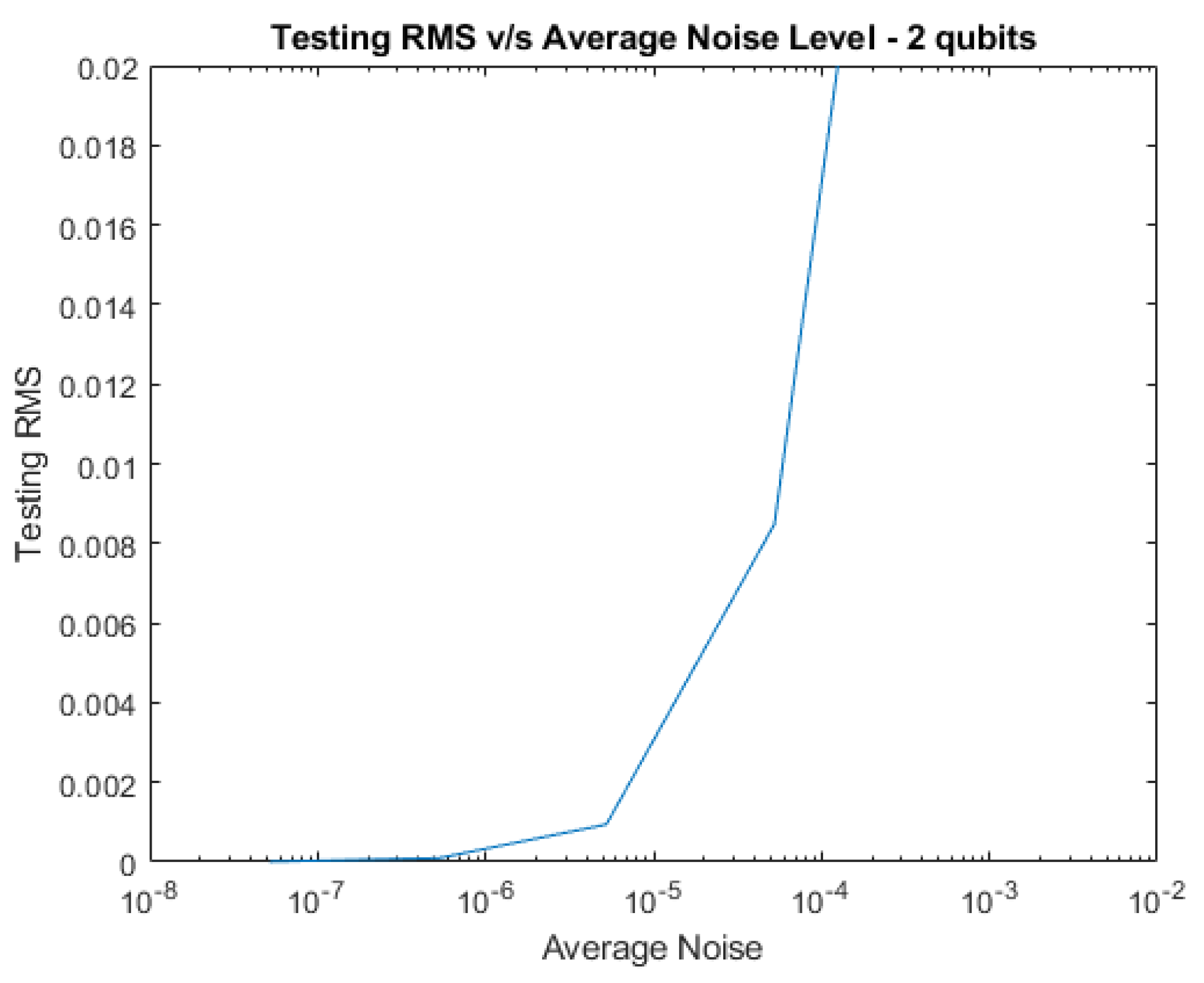

| RNP | Pure Noise RMS | Decoherence RMS | Complex Noise RMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1e-6 | |||

| 1e-5 | |||

| 1e-4 | 0.0019 | 0.0047 | 0.0085 |

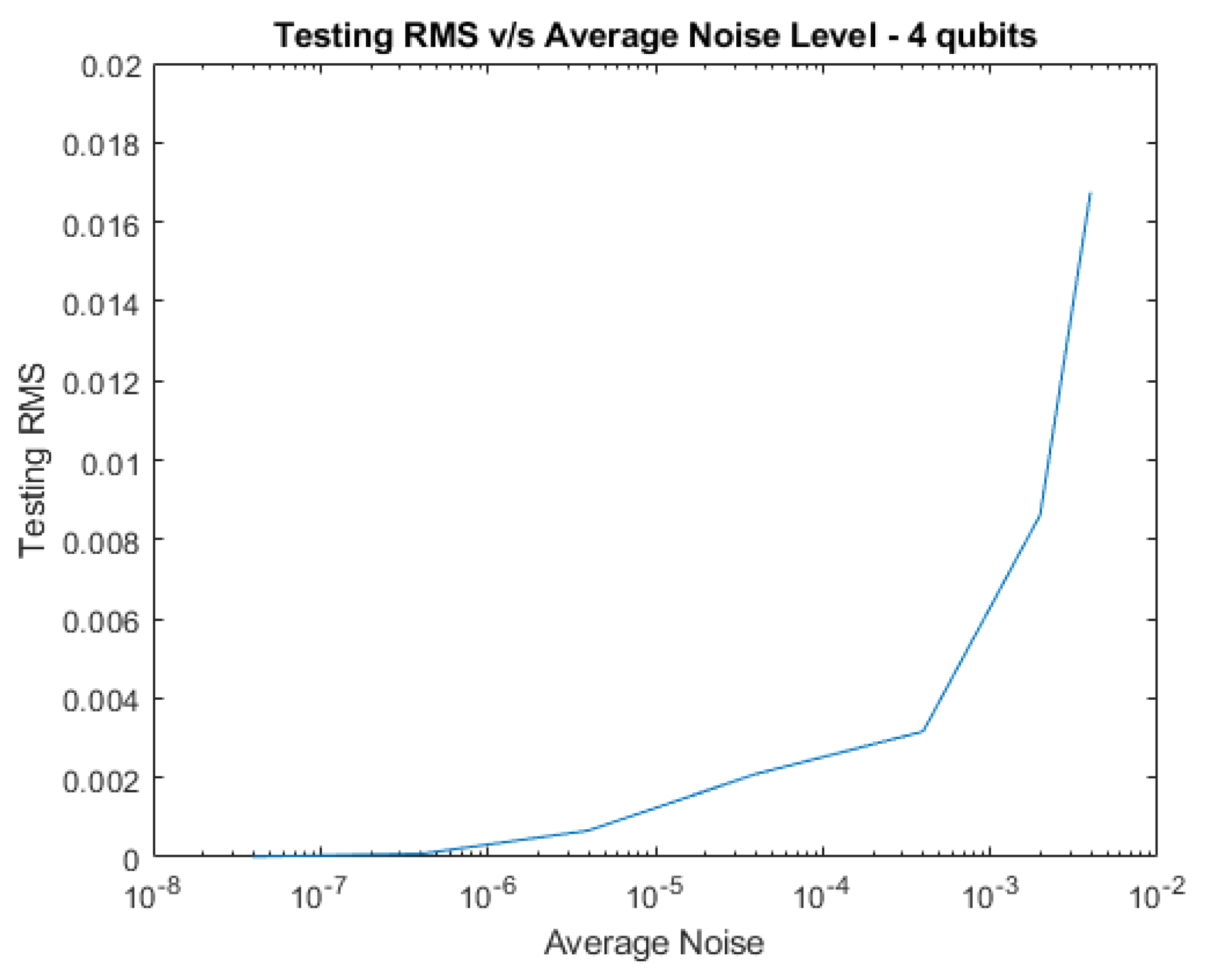

| RNP | Pure Noise RMS | Decoherence RMS | Complex Noise RMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1e-6 | |||

| 1e-5 | |||

| 1e-4 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 |

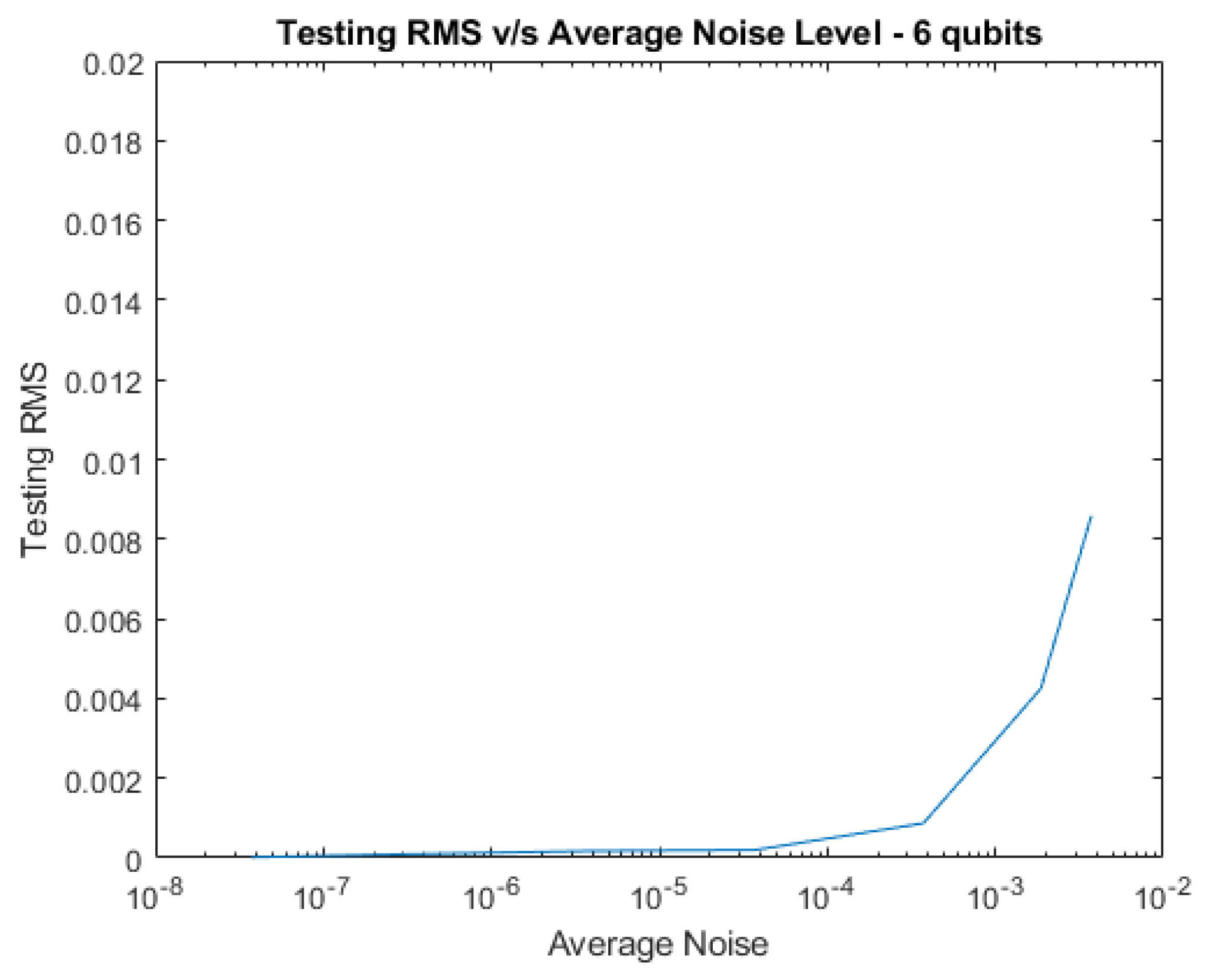

| RNP | Pure Noise RMS | Decoherence RMS | Complex Noise RMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1e-6 | |||

| 1e-5 | |||

| 1e-4 |

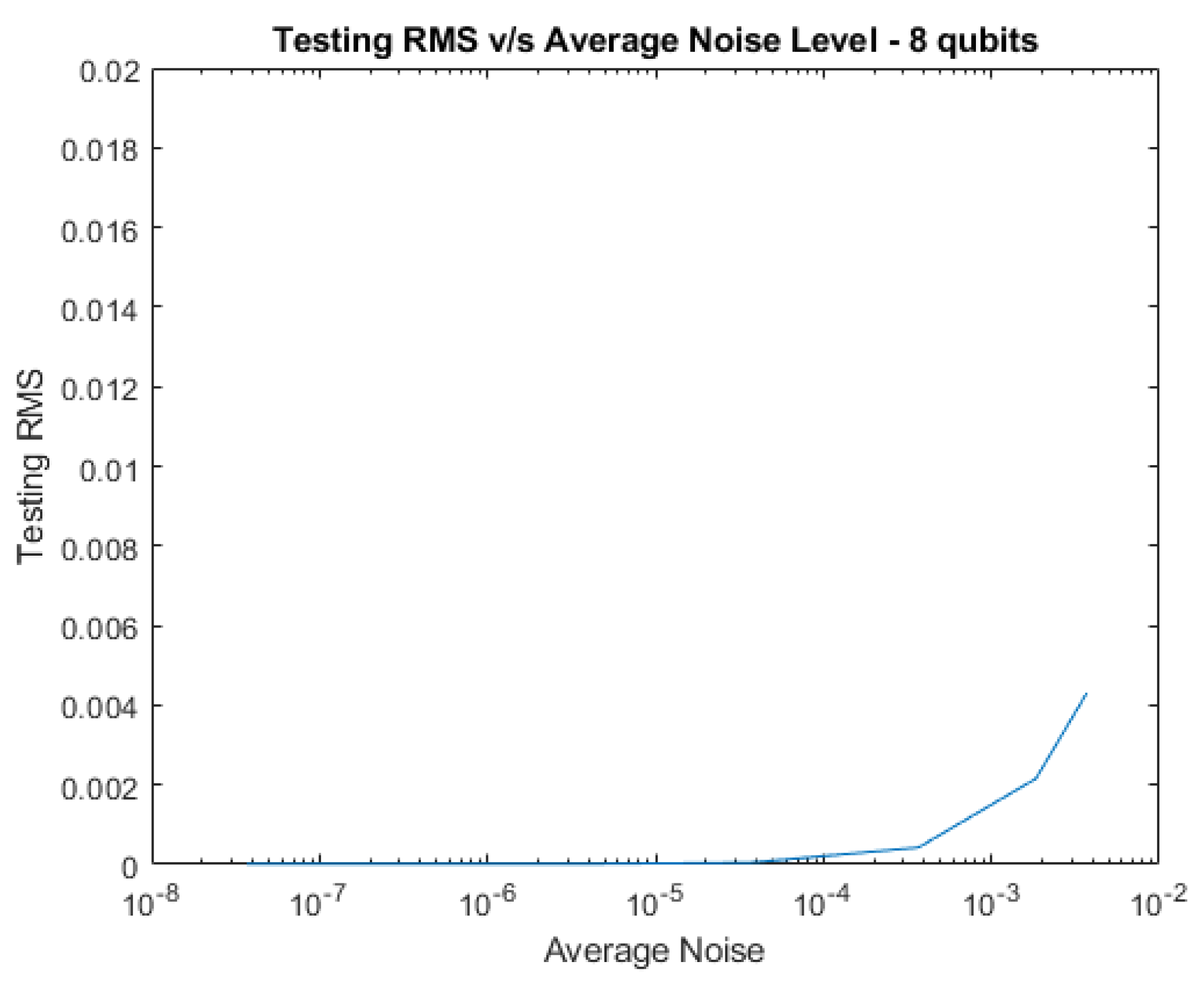

| RNP | Pure Noise RMS | Decoherence RMS | Complex Noise RMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1e-6 | |||

| 1e-5 | |||

| 1e-4 |

Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Dieks, D. Communication by EPR devices. Physics Letters A 1982, 92, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootters, W.K.; Zurek, W.H. A single quantum cannot be cloned. Nature 1982, 299, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briegel, H.J.; Dür, W.; Cirac, J.I.; Zoller, P. Quantum repeaters for communication, 1998, [arXiv:quant-ph/quant-ph/9803056].

- Pan, J.W.; Bouwmeester, D.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Experimental entanglement swapping: entangling photons that never interacted. Physical review letters 1998, 80, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Patil, A.; Guha, S. Measurement-Based Entanglement Distillation and Constant-Rate Quantum Repeaters over Arbitrary Distances. 2025; arXiv:2502.11174 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Jie, Q.X.; Li, M.; Wu, S.H.; Wang, Z.B.; Zou, X.B.; Zhang, P.F.; Li, G.; Zhang, T.; Guo, G.C.; et al. Proposal of quantum repeater architecture based on Rydberg atom quantum processors. 2024; arXiv:2410.12523 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, J.M.; Huber-Loyola, T.; Hofling, S. Quantum dots for quantum repeaters, 2025. arXiv:quant-ph/2503.13775].

- Cussenot, P.; Grivet, B.; Lanyon, B.P.; Northup, T.E.; de Riedmatten, H.; Sørensen, A.S.; Sangouard, N. Uniting Quantum Processing Nodes of Cavity-coupled Ions with Rare-earth Quantum Repeaters Using Single-photon Pulse Shaping Based on Atomic Frequency Comb. 2025; arXiv:2501.18704 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chelluri, S.S.; Sharma, S.; Schmidt, F.; Kusminskiy, S.V.; van Loock, P. Bosonic quantum error correction with microwave cavities for quantum repeaters. 2025; arXiv:2503.21569 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.; Azar, M.; Chandra, N.K.; Jin, X.; Cheng, J.; Seshadreesan, K.P.; Liu, J. Quantum repeaters enhanced by vacuum beam guides. 2025; arXiv:2504.13397 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mor-Ruiz, M.F.; Miguel-Ramiro, J.; Wallnöfer, J.; Coopmans, T.; Dür, W. Merging-based quantum repeater. 2025; arXiv:2502.04450 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mastriani, M. Simplified entanglement swapping protocol for the quantum Internet. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, E.C.; Steck, J.E.; Kumar, P.; Walsh, K.A. Quantum algorithm design using dynamic learning. Quantum Information and Computation, vol. 8, No. 1 and 2, pp. 12-29 (2008).

- Behrman, E.; Steck, J. Multiqubit entanglement of a general input state. Quantum Information and Computation 13, 36-53, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.; Nguyen, N.; Behrman, E.; Steck, J. Experimental pairwise entanglement estimation for an N-qubit system: A machine learning approach for programming quantum hardware. Quantum Information Processing 19, 1-18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, E.; Nguyen, N.; Steck, J.; McCann, M. Quantum neural computation of entanglement is robust to noise and decoherence. In Quantum Inspired Computational Intelligence; Bhattacharyya, S., Maulik, U., Dutta, P., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: Boston, 2017; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Behrman, E.C.; Steck, J.E. Quantum Learning with Noise and Decoherence: A Robust Quantum Neural Network. Quantum Machine Intelligence 2(1), 1-15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nola, J.; Sanchez, U.; Murthy, A.K.; Behrman, E.; Steck, J. Training microwave pulses using machine learning. Academia Quantum, 2025 (to appear). [Google Scholar]

- Rethinam, M.; Javali, A.; Hart, A.; Behrman, E.; Steck, J. A genetic algorithm for finding pulse sequences for nmr quantum computing. Paritantra – Journal of Systems Science and Engineering 20, 32-42, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roweis, S. Levenberg-Marquardt Optimization. https://people.duke.edu/ hpgavin/SystemID/References/lm-Roweis.pdf.

- Levenberg, K. A Method for the Solution of Certain Non-Linear Problems in Least Squares. Quarterly of Applied Mathematics 2 1944, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D. An Algorithm for Least-Squares Estimation of Nonlinear Parameters. Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1963; 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- More, J.J. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: Implementation and theory 1978. pp. 431–441.

- Steck, J.E.; Thompson, N.L.; Behrman, E.C. Programming Quantum Hardware via Levenberg-Marquardt Machine Learning. In Intelligent Quantum Information Processing; CRC Press, 2024.

- Transtrum, M.K.; Sethna, J.P. Improvements to the Levenberg Marquardt algorithm for nonlinear least- squares minimization. 2012; arXiv:1201.5885 2012. [Google Scholar]

- M. K. Transtrum, B.B.M.; Sethna, J.P. Geometry of nonlinear least squares with applications to sloppy models and optimization. Physical Review E 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Cao, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Hou, S.Y.; Xu, P.; Zeng, B. Simulating noisy quantum circuits with matrix product density operators. Physical review research 2021, 3, 023005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trained RMS | |

|---|---|

| 2 | |

| 4 | |

| 6 | |

| 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).