Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. RMSSD and the Poincaré plot

3.2. Fourier-components versus RMSSD and SDNN

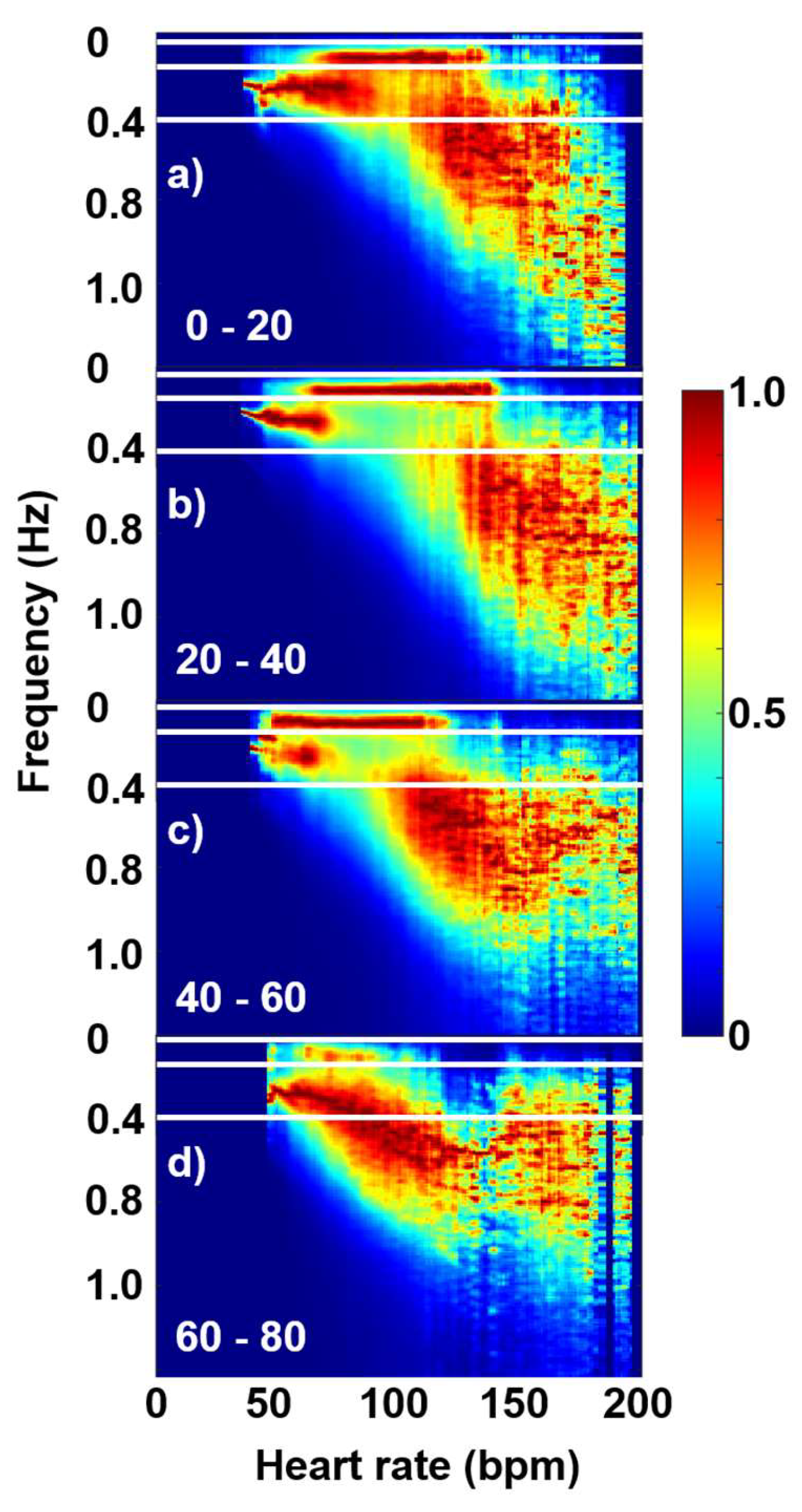

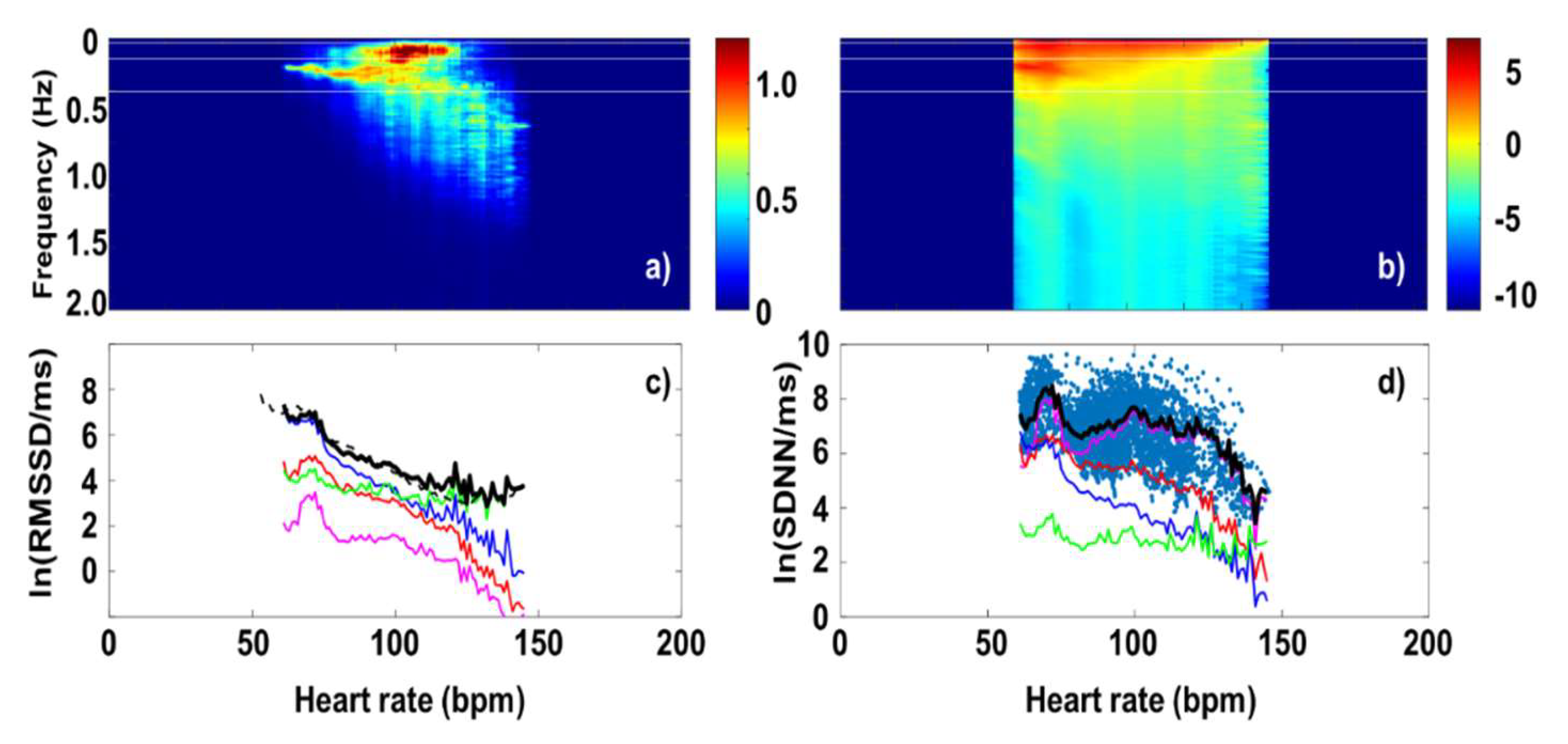

3.3. Fourier-components versus nonlinear measures (DFA and SampEn)

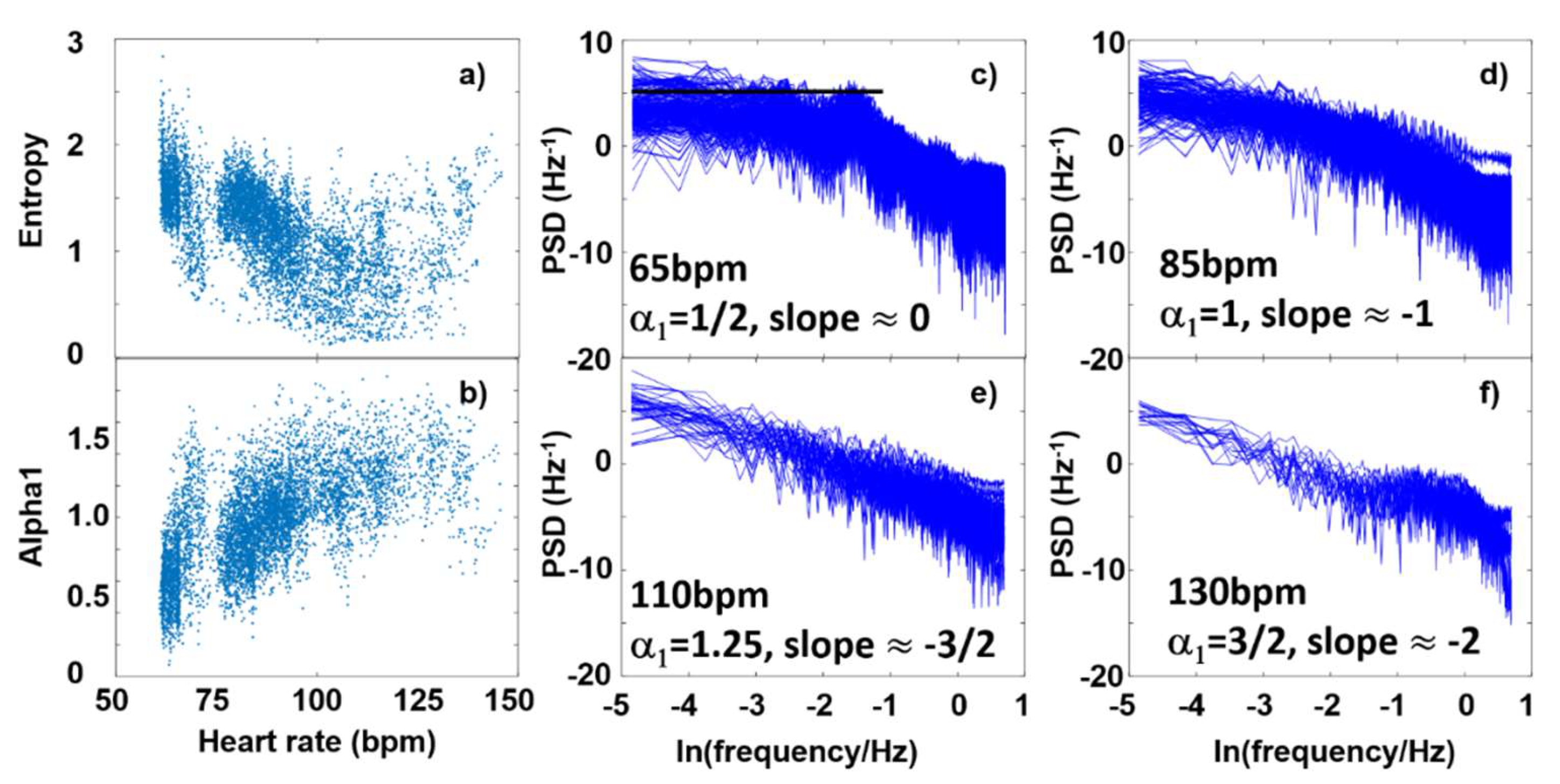

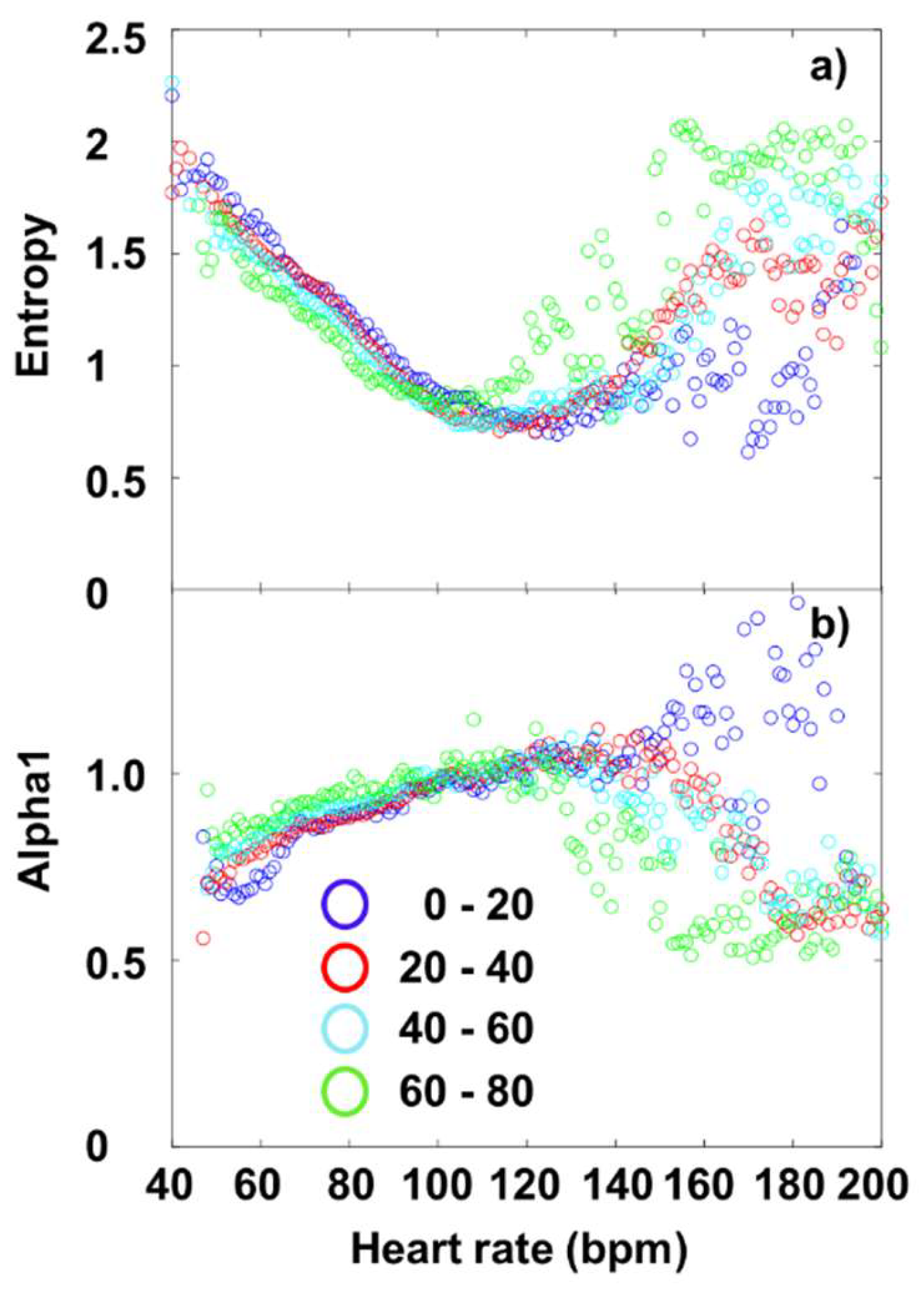

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| DFA | Detrended fluctuation analysis |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| HF | High-frequency |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| LF | Low-frequency |

| MC | Master Curve |

| NN | Normal-to-normal RR intervals (NN and RR are used here synonymously) |

| PNS | Parasympathetic nervous system |

| RMSSD | Root mean square of successive differences |

| RR; dRR | Length of the RR interval, Length-difference of successive RR intervals |

| SampEn | Sample entropy |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| THEW | Telemetric- and Holter-ECG Warehouse |

| VHF | Very-high-frequency |

| VLF | Very-low-frequency |

References

- Billman, G.E. Heart Rate Variability ? A Historical Perspective. Front. Physio. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Implication of Different Factors on Heart Rate Variability. CCR 2021, 17, e160721189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatisson, J.; Oswald, V.; Lalonde, F. Influence Diagram of Physiological and Environmental Factors Affecting Heart Rate Variability: An Extended Literature Overview. Heart International 2016, 11, heartint.500023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammito, S.; Böckelmann, I. Factors Influencing Heart Rate Variability. ICFJ 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, M.; Parati, G. Variables Influencing Heart Rate. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2009, 52, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiweck, C.; Piette, D.; Berckmans, D.; Claes, S.; Vrieze, E. Heart Rate and High Frequency Heart Rate Variability during Stress as Biomarker for Clinical Depression. A Systematic Review. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloter, E.; Barrueto, K.; Klein, S.D.; Scholkmann, F.; Wolf, U. Heart Rate Variability as a Prognostic Factor for Cancer Survival – A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Niskanen, J.-P.; Lipponen, J.A.; Ranta-aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Kubios HRV – Heart Rate Variability Analysis Software. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2014, 113, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva-Tsaneva, G.N. Time and Frequency Analysis of Heart Rate Variability Data in Heart Failure Patients. IJACSA 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamen, P.W.; Tonkin, A.M. Application of the Poincaré Plot to Heart Rate Variability: A New Measure of Functional Status in Heart Failure. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine 1995, 25, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, A.E.; Press, S.A.; Helmert, E.; Hautzinger, M.; Khazan, I.; Vagedes, J. Comparing Effectiveness of HRV-Biofeedback and Mindfulness for Workplace Stress Reduction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2020, 45, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-G.; Cheon, E.-J.; Bai, D.-S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.-H. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-M.; Wang, S.-Y.; Fan, S.-Y.; Peper, E.; Chen, S.-P.; Huang, C.-Y. A Single Session of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Produced Greater Increases in Heart Rate Variability Than Autogenic Training. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2020, 45, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijken, N.H.; Soer, R.; De Maar, E.; Prins, H.; Teeuw, W.B.; Peuscher, J.; Oosterveld, F.G.J. Increasing Performance of Professional Soccer Players and Elite Track and Field Athletes with Peak Performance Training and Biofeedback: A Pilot Study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2016, 41, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billman, G.E. The Effect of Heart Rate on the Heart Rate Variability Response to Autonomic Interventions. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. The LF/HF Ratio Does Not Accurately Measure Cardiac Sympatho-Vagal Balance. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacha, J.; Barabach, S.; Statkiewicz-Barabach, G.; Sacha, K.; Müller, A.; Piskorski, J.; Barthel, P.; Schmidt, G. How to Strengthen or Weaken the HRV Dependence on Heart Rate — Description of the Method and Its Perspectives. International Journal of Cardiology 2013, 168, 1660–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfredi, O.; Lyashkov, A.E.; Johnsen, A.-B.; Inada, S.; Schneider, H.; Wang, R.; Nirmalan, M.; Wisloff, U.; Maltsev, V.A.; Lakatta, E.G.; et al. Biophysical Characterization of the Underappreciated and Important Relationship Between Heart Rate Variability and Heart Rate. Hypertension 2014, 64, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. LF Power of HRV Could Be the Piezo2 Activity Level in Baroreceptors with Some Piezo1 Residual Activity Contribution. IJMS 2023, 24, 7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Búzás, A.; Makai, A.; Groma, G.I.; Dancsházy, Z.; Szendi, I.; Kish, L.B.; Santa-Maria, A.R.; Dér, A. Hierarchical Organization of Human Physical Activity. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart Rate Variability: Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation and Clinical Use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, H.; Venditti, F.J.; Manders, E.S.; Evans, J.C.; Larson, M.G.; Feldman, C.L.; Levy, D. Determinants of Heart Rate Variability. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996, 28, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyett, M.; Wang, Y.; D’Souza, A. CrossTalk Opposing View: Heart Rate Variability as a Measure of Cardiac Autonomic Responsiveness Is Fundamentally Flawed. The Journal of Physiology 2019, 597, 2599–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roon, A.M.; Snieder, H.; Lefrandt, J.D.; De Geus, E.J.C.; Riese, H. Parsimonious Correction of Heart Rate Variability for Its Dependency on Heart Rate. Hypertension 2016, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platisa, M.M.; Gal, V. Dependence of Heart Rate Variability on Heart Period in Disease and Aging. Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzas, A.; Horvath, T.; Der, A. A Novel Approach in Heart-Rate-Variability Analysis Based on Modified Poincaré Plots. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36606–36615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsior, J.S.; Sacha, J.; Jeleń, P.J.; Pawłowski, M.; Werner, B.; Dąbrowski, M.J. Interaction Between Heart Rate Variability and Heart Rate in Pediatric Population. Front Physiol 2015, 6, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudics, E.; Buzás, A.; Pálfi, A.; Szabó, Z.; Nagy, Á.; Hompoth, E.A.; Dombi, J.; Bilicki, V.; Szendi, I.; Dér, A. Quantifying Stress and Relaxation: A New Measure of Heart Rate Variability as a Reliable Biomarker. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platisa, M.M.; Gal, V. Reflection of Heart Rate Regulation on Linear and Nonlinear Heart Rate Variability Measures. Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platisa, M.M.; Gal, V. Correlation Properties of Heartbeat Dynamics. Eur Biophys J 2008, 37, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platisa, M.M.; Nestorovic, Z.; Damjanovic, S.; Gal, V. Linear and Non-linear Heart Rate Variability Measures in Chronic and Acute Phase of Anorexia Nervosa. Clin Physio Funct Imaging 2006, 26, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platisa, M.M.; Mazic, S.; Nestorovic, Z.; Gal, V. Complexity of Heartbeat Interval Series in Young Healthy Trained and Untrained Men. Physiol. Meas. 2008, 29, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva-Tsaneva, G.N. INVESTIGATION OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY BY STATISTICAL METHODS AND DETRENDED FLUCTUATION ANALYSIS. CBUP 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva-Tsaneva, G.; Gospodinova, E.; Cheshmedzhiev, K. Examination of Cardiac Activity with ECG Monitoring Using Heart Rate Variability Methods. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodinov, M.; Gospodinova, E.; Georgieva-Tsaneva, G. Mathematical Methods of ECG Data Analysis. In Healthcare Data Analytics and Management; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 177–209 ISBN 978-0-12-815368-0.

- Gospodinova, E.; Lebamovski, P.; Georgieva-Tsaneva, G.; Negreva, M. Evaluation of the Methods for Nonlinear Analysis of Heart Rate Variability. Fractal Fract 2023, 7, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribbin, B.; Pickering, T.G.; Sleight, P.; Peto, R. Effect of Age and High Blood Pressure on Barorefiex Sensitivity in Man. Circulation Research 1971, 29, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, K.D. Effect of Aging on Baroreflex Function in Humans. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2007, 293, R3–R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couderc, J.-P. A Unique Digital Electrocardiographic Repository for the Development of Quantitative Electrocardiography and Cardiac Safety: The Telemetric and Holter ECG Warehouse (THEW). Journal of Electrocardiology 2010, 43, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.S.; Moorman, J.R. Physiological Time-Series Analysis Using Approximate Entropy and Sample Entropy. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2000, 278, H2039–H2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magris, Martin Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA).

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Measurement in Medicine: The Analysis of Method Comparison Studies. The Statistician 1983, 32, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Báez, M.; Machado, C.; Montes-Brown, J.; Jas-García, J.; Leisman, G.; Schiavi, A.; Machado-García, A.; Carricarte-Naranjo, C.; Carmeli, E. Very High Frequency Oscillations of Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Humans and in Patients with Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy. In Progress in Medical Research; Pokorski, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-89664-9. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, M.D.; Thompson, J.M.; Kaye, D.M.; Turner, A.G.; Jennings, G.L.; Cox, H.S.; Lambert, G.W.; Seals, D.R. Effects of Aging on the Responsiveness of the Human Cardiac Sympathetic Nerves to Stressors. Circulation 1995, 91, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, W. Advanced Calculus; 4. ed., 5. reprint. with corr.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, Mass, 1994; ISBN 978-0-201-57888-1. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni, P.; Lazzeroni, D.; Coruzzi, P.; Faini, A. Multifractal-Multiscale Analysis of Cardiovascular Signals: A DFA-Based Characterization of Blood Pressure and Heart-Rate Complexity by Gender. Complexity 2018, 2018, 4801924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.D.; Collison, D. The Normal Range and Determinants of the Intrinsic Heart Rate in Man. Cardiovascular Research 1970, 4, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Gupta, A.; Sohal, J.S.; Singh, A. A Unified Non-Linear Approach Based on Recurrence Quantification Analysis and Approximate Entropy: Application to the Classification of Heart Rate Variability of Age-Stratified Subjects. Med Biol Eng Comput 2019, 57, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Definition | Mathematical formula |

| RMSSD | Measures short-term HRV based on the square root of the mean of the N−1 squared differences between adjacent RR intervals. Reflects parasympathetic activity. | |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of all RR intervals. Reflects overall HRV (both sympathetic and parasympathetic). | |

| VLF (Very Low Frequency) | Power in the very low frequency range (0.0033-0.04 Hz). Linked to thermoregulation, hormones, and other slow-acting regulatory mechanisms. |

F Fourier transform of RR time series |

| LF (Low Frequency) | Power in the low frequency range (0.04–0.15 Hz). Reflects both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. | |

| HF (High Frequency) | Power in the high frequency range (0.15–0.40 Hz). Mainly reflects parasympathetic (vagal) activity, associated with respiration. | |

| VHF (Very High Frequency) | Power in the very high frequency range (>0.4 Hz). May reflect noise or specific physiological phenomena. | |

| Entropy (SampEn, ApEn) | Measures the complexity or unpredictability of RR interval time series. Higher entropy = more complex signal. [41] | SampEn(m, r, N) = ln(A/B) N number of vector pairs in our case |

| DFA (Detrended Fluctuation Analysis) | Detects fractal scaling properties in HRV, capturing long-range correlations. Useful in non-stationary data. [42] | is scaling exponent(s=10, 20, …, 100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).