Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

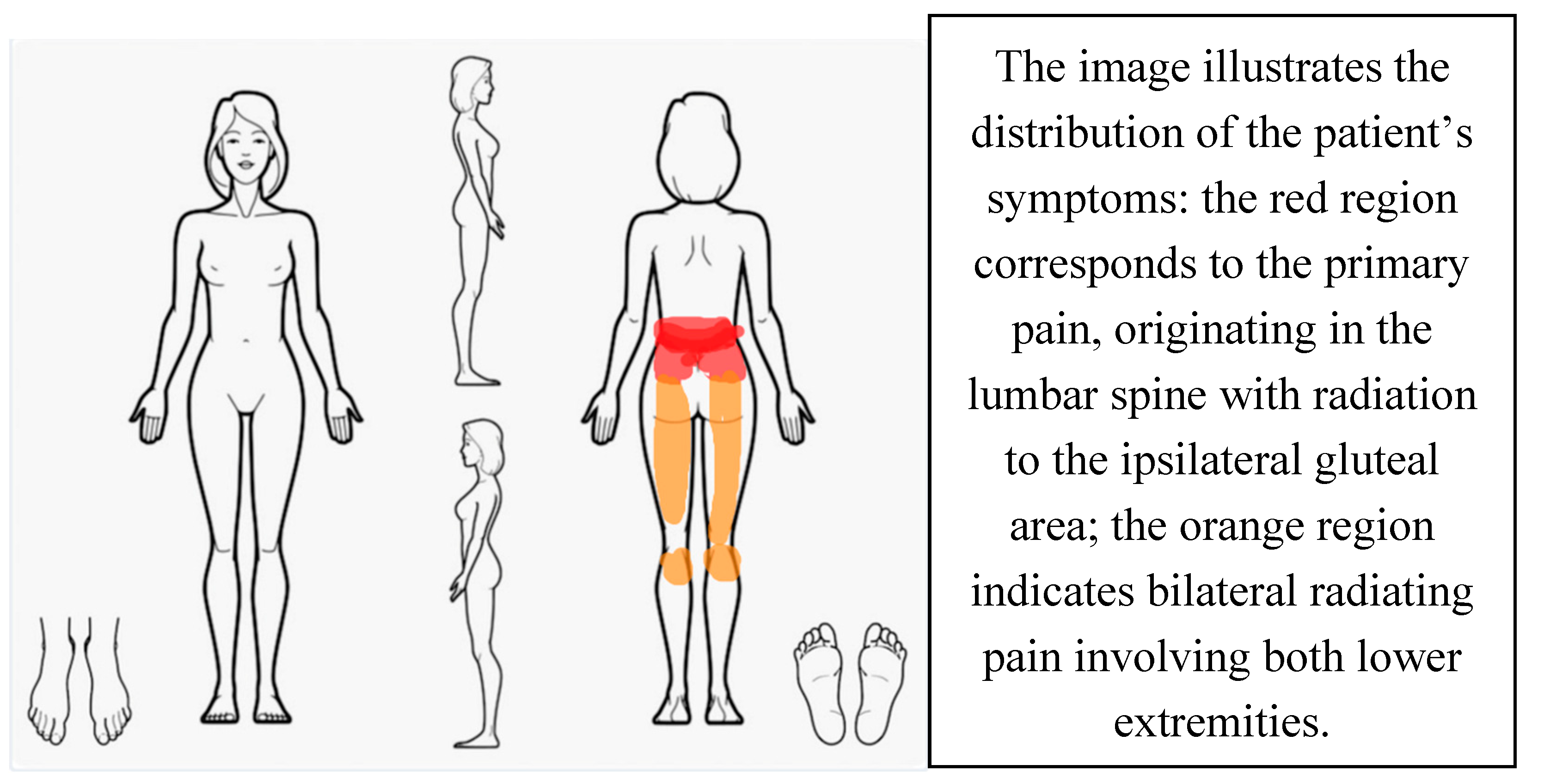

Case Presentation

Patient History

Physical Examination

Treatment

| BASELINE | AFTER DIAGNOSIS | 4 MONTHS SINCE DIAGNOSIS | 6 MONTHS SINCE DIAGNOSIS | |

| NPRS | 8 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| ODI | 64% | 62% | 44% | 14% |

Discussion

Conclusion

Informed Consent

Disclosure

Abbreviations

| OMPT | Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapist |

| NPRS | Numerical Pain Rating Scale |

| LBP | low back pain |

| SLR | Straight Leg Raise |

| PGP | Pelvic Girdle Pain |

| LDL | Long Dorsal Sacroiliac Ligament |

| TrPs | Trigger Points |

| ODI | Oswestry Disability Index |

| MT | Manual Therapy |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Agarwal, N. , Subramanian, A., 2010. Endometriosis – Morphology, Clinical Presentations and Molecular Pathology. J. Lab. Physicians 2, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen, O. , Brox, J.I., Cedraschi, C., Hildebrandt, J., Klaber-Moffett, J., Kovacs, F., Mannion, A.F., Reis, S., Staal, J.B., Ursin, H., Zanoli, G., COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain, 2006. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 15 Suppl 2, S192-300. [CrossRef]

- Aredo, J.V. , Heyrana, K.J., Karp, B.I., Shah, J.P., Stratton, P., 2017. Relating Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis to Signs of Sensitization and Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Semin. Reprod. Med. 35, 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P. , 2003. Endometriosis is associated with central sensitization: a psychophysical controlled study. J. Pain 4, 372–380. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.G. , Campo, G., Papaleo, E., Marazziti, D., Maremmani, I., 2021. The Importance of a Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Endometriotic Patients: The Relationship between Endometriosis and Psychic Vulnerability. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1616. [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, M. , Bounous, V.E., Clarizia, R., Mautone, D., Mabrouk, M., 2019. Recurrent endometriosis: a battle against an unknown enemy. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care Off. J. Eur. Soc. Contracept. 24, 464–474. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. , Xie, W., Strong, J.A., Jiang, J., Zhang, J.-M., 2016. Sciatic endometriosis induces mechanical hypersensitivity, segmental nerve damage, and robust local inflammation in rats. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 20, 1044–1057. [CrossRef]

- Crump, J. , Suker, A., White, L., 2024. Endometriosis: A review of recent evidence and guidelines. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 53, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Denny, E. , 2004. Women’s experience of endometriosis. J. Adv. Nurs. 46, 641–648. [CrossRef]

- Dessole, M. , Melis, G. Endometriosis in Adolescence. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012, 869191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.C. , Kho, K.A., Morozov, V.V., Kearney, S., Zurawin, J.L., Nezhat, C.H., 2015. Endometriosis in Adolescents. JSLS 19, e2015.00019. [CrossRef]

- Endometriosis guideline [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.eshre.eu/guideline/endometriosis (accessed 4.21.25).

- Facchin, F. , Barbara, Giussy, Saita, Emanuela, Mosconi, Paola, Roberto, Anna, Fedele, Luigi, and Vercellini, P., 2015. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and mental health: pelvic pain makes the difference. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 36, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.Y. , Campbell, N., Mooney, S.S., Holdsworth-Carson, S.J., Tyson, K., 2024. Evidence for the role of multidisciplinary team care in people with pelvic pain and endometriosis: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 64, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.R. , Keeler, E.R., Euscher, E.D., McCutcheon, I.E., 2011. Cyclic sciatica from extrapelvic endometriosis affecting the sciatic nerve. [CrossRef]

- Fourquet, J. , Báez, L., Figueroa, M., Iriarte, R.I., Flores, I., 2011. Quantification of the Impact of Endometriosis Symptoms on Health Related Quality of Life and Work Productivity. Fertil. Steril. 96, 107–112. [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z. , Fritz, J.M., Silfies, S.P., Schneider, M.J., Beneciuk, J.M., Lentz, T.A., Gilliam, J.R., Hendren, S., Norman, K.S., 2021. Interventions for the Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 51, CPG1–CPG60. [CrossRef]

- Hudelist, G. , Fritzer, N., Thomas, A., Niehues, C., Oppelt, P., Haas, D., Tammaa, A., Salzer, H., 2012. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3412–3416. [CrossRef]

- Laslett, M. , Williams, M., 1994. The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine 19, 1243–1249. [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, J. , Kohl Schwartz, A.S., Geraedts, K., Haeberlin, F., Eberhard, M., von Orellie, S., Imesch, P., Leeners, B., 2022. Living with endometriosis: Comorbid pain disorders, characteristics of pain and relevance for daily life. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 26, 1021–1038. [CrossRef]

- May, S. , Aina, A., 2012. Centralization and directional preference: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 17, 497–506. [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M. , Baiardi, P., Ferrari, S., Foti, C., Mugnai, R., Pillastrini, P., Vanti, C., Zanoli, G., 2009. Development of the Italian version of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI-I): A cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity study. Spine 34, 2090–2095. [CrossRef]

- Oertel, J. , Sharif, S., Zygourakis, C., Sippl, C., 2024. Acute low back pain: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention: WFNS spine committee recommendations. World Neurosurg. X 22, 100313. [CrossRef]

- Sachedin, A. , Todd, N., 2020. Dysmenorrhea, Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 12, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y. , Laufer, M.R., 2020. Adolescent Endometriosis: An Update. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 33, 112–119. [CrossRef]

- Skytte, L. , May, S., Petersen, P., 2005. Centralization: its prognostic value in patients with referred symptoms and sciatica. Spine 30, E293-299. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. , Coyne,Karin S., Zaiser,Erica, Castelli-Haley,Jane, and Fuldeore, M.J., 2017. The burden of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life in women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 38, 238–248. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y. , Jung, Y.W., Shin, W., Park, M., Lee, G.W., Jeong, S., An, S., Kim, K., Ko, Y.B., Lee, K.H., Kang, B.H., Lee, M., Yoo, H.J., 2023. Endometriosis-Related Chronic Pelvic Pain. Biomedicines 11, 2868. [CrossRef]

- Tawa, N. , Rhoda, A., Diener, I., 2017. Accuracy of clinical neurological examination in diagnosing lumbo-sacral radiculopathy: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18, 93. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S. , Kotlyar, A.M., Flores, V.A., 2021. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. The Lancet 397, 839–852. [CrossRef]

- Uppal, J. , Sobotka, S., Jenkins III, A.L., 2017. Cyclic sciatica and back pain responds to treatment of underlying endometriosis: case illustration. World Neurosurg. 97, 760-e1.

- Vleeming, A. , Albert, H.B., Ostgaard, H.C., Sturesson, B., Stuge, B., 2008. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform. Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 17, 794–819. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A. , Hoggart, B., 2005. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 14, 798–804. [CrossRef]

- Woolf, A.D. , Pfleger, B., 2003. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull. World Health Organ. 81, 646–656.

- Wu, Z. , Huang, G., Ai, J., Liu, Y., Pei, B., 2024. The burden of low back pain in adolescents and young adults. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 37, 955–966. [CrossRef]

- Zaina, F. , Côté, P., Cancelliere, C., Di Felice, F., Donzelli, S., Rauch, A., Verville, L., Negrini, S., Nordin, M., 2023. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Persons With Non-specific Low Back Pain With and Without Radiculopathy: Identification of Best Evidence for Rehabilitation to Develop the WHO’s Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 104, 1913–1927. [CrossRef]

- Zanette, G. , Magrinelli, F., Tamburin, S., 2014. Periodic thigh pain from radicular endometriosis. Pract. Neurol. 14, 351–353. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).