1. Introduction

Anacardium occidentale is the most studied species of the Anacardaceae family. It is native from tropical and subtropical areas of the American continent, mainly from the northern region of Brazil -where there is called caju- which is the main producer of derivatives of this plant for economic purposes [

1,

2]. The parts of this plant are known for their medicinal and nutraceutical properties. Regarding its biological characteristics, it is an evergreen tree that grows 10 to 15m tall with a short, irregularly shaped trunk. The stem is used for timber purposes, the fruit and nut are used as food, the leaves and flowers have been used in traditional medicine to treat skin lesions, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal disorders [

3]. These parts of the plant are rich in compounds with biological activity such as anacardic acids, gallic acid, polyphenols and flavonoids [

4]. With respect to biological activity,

in vitro studies using crude ethanolic extracts of leaves, bark and flower have demonstrated neuroprotective [

5], antioxidant [

6], antitumoral [

7] effects. Additionally, its inhibitory activity on important infectious agents in public health has been described against

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Candida albicans [

8,

9,

10].

On its antifungal activity, we described previously that

A. occidentale leaves extract inhibited the proliferation and growth of

C. albicans at concentrations of 62.5 and 125 μg/mL through the accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial dysfunction with low cytotoxicity or hemolytic activity [

11]. Agathisflavone is one of the major components among the flavonoids present in this plant [

12]. This compound is a biflavonoid, obtained by the C-C coupling of two apigenin molecules [

13]. It has some important antiviral activities, including anti-influenzae and anti SARS-CoV2 [

14], antimicrobial and antioxidant [

6]. However, its antifungal activity has not been reported to date. Since biflavonoids can form complexes with yeast cell wall proteins and disrupt their fluidity and integrity [

15]. It would be interesting to know if this compound can contribute significantly to the antifungal activity demonstrated by the

A. occidentale ethanolic extract.

For the isolation and purification of agathisflavone, the most widely used technique has been separation using a Sephadex LH-20 column, since this molecule is usually isolated in small quantities due to its low yields [

6,

16,

17]. However, biflavonoids such as AGF can establish undesirable interactions between their functional groups and the solid phase of sephadex and present impurities in the eluted product [

18,

19]. In this context, the CPC purification method was used, this is an efficient and innovative strategy widely used in the extraction of compounds such as alkaloids, terpenes, saponins, carotenoids and flavonoids [

20]. CPC is based on the principles of liquid/liquid chromatography, where the stationary phase is retained by centrifugal force inside the rotor while the mobile phase flows, ensuring no loss due to adsorption and the entire sample is recovered after the run [

21]. CPC offers notable advantages over solid-state separation using Sephadex, such as being more suitable for highly apolar molecules, better separation in complex samples, higher speed, and easier scale-up [

20,

22]. Currently, it has not been previously reported for use for the isolation of

A.occidentale compounds. In the present study, an efficient one single CPC run method for the isolation of AGF from an ethyl acetate fraction (EtOAc) was carried out. Moreover, his role on the antifungal activity previously reported for

A. occidentale leaves extract was evaluated. The results showed that AGF showed a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 250 μg/mL against

Candida albicans and did not show cytotoxicity at the concentrations tested.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation of AGF

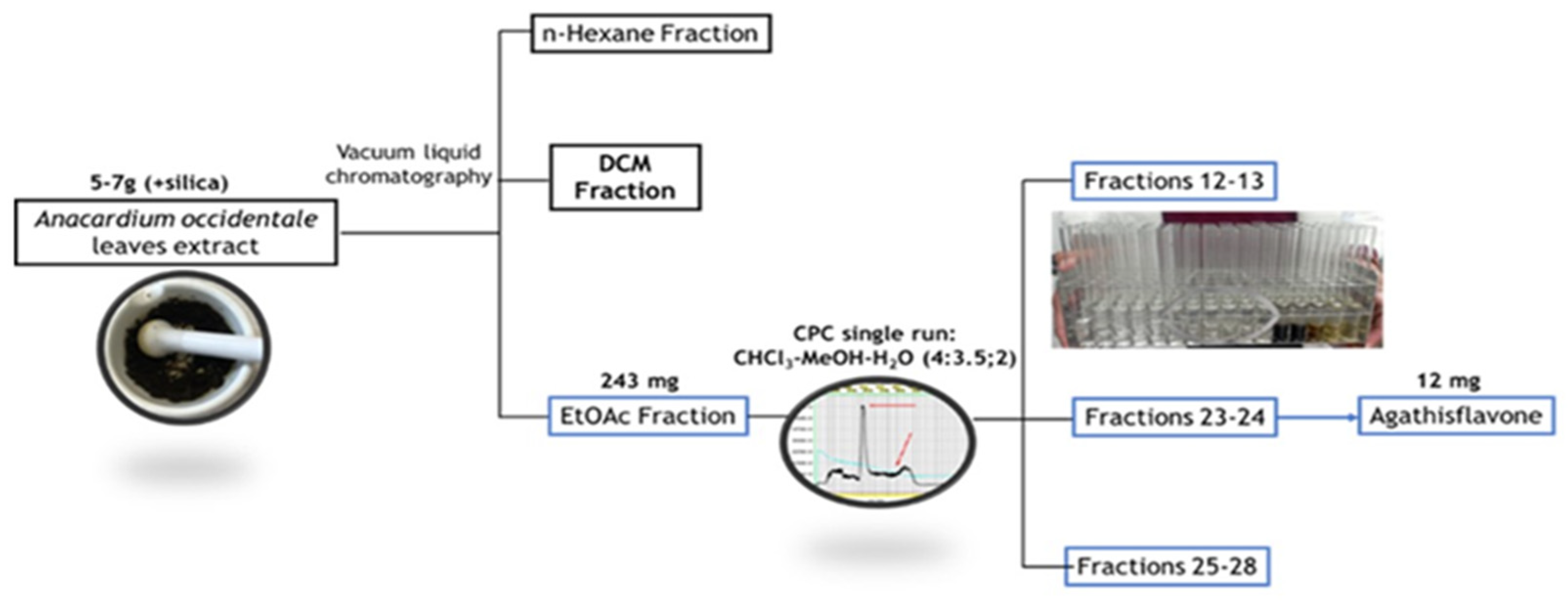

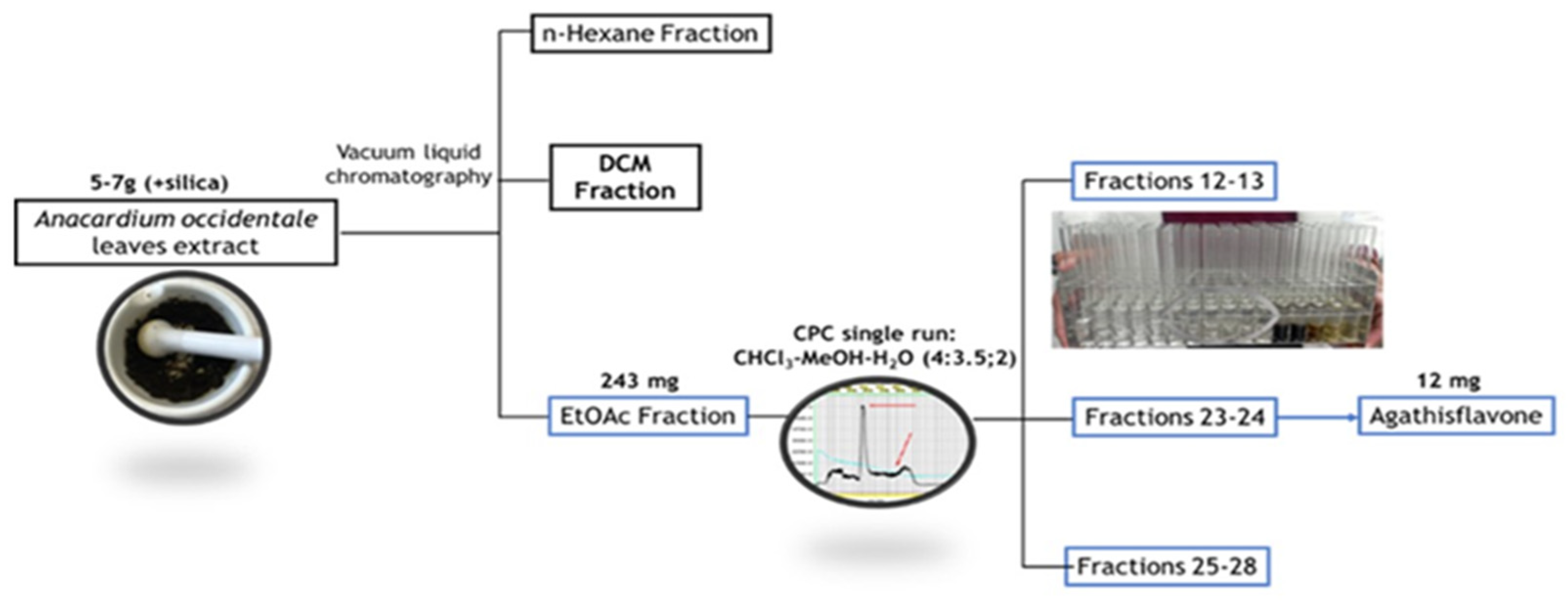

The

A. occidentale crude extract underwent fractionation on silica gel mesh. At the end of the process, three fractions were obtained: hexane (n-HEX), dichloromethane (DCM) and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) fractions (Fig 1). All fractions were dried and analyzed by UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS under the same initial conditions established for the extract [

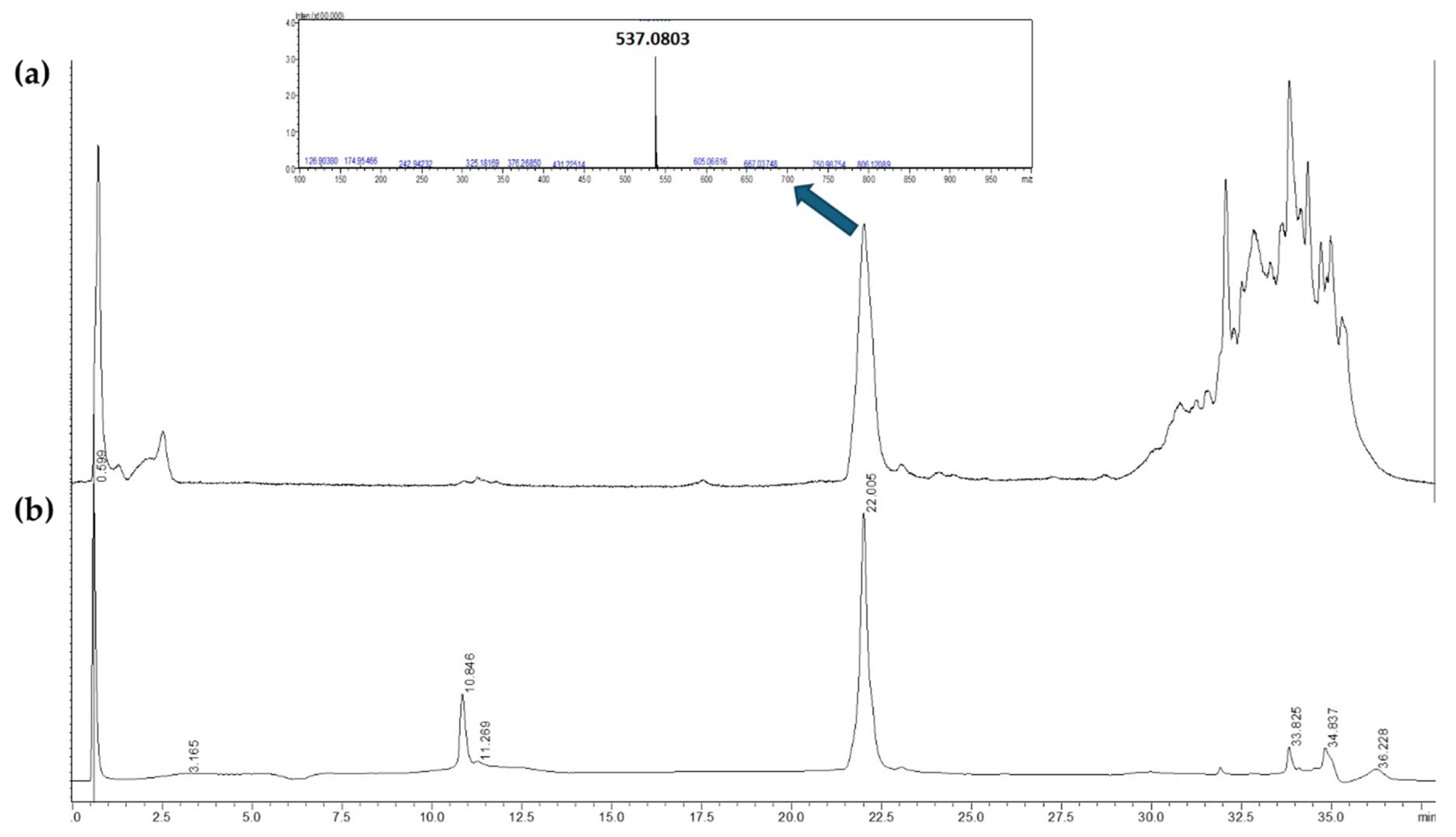

11] to confirm the presence of AGF by the analysis of its retention time, UV-Vis and MS spectrum, under the method described. Only the EtOAc fraction contained the compound of interest (Fig 2).

Figure 1.

phytochemical isolation of AGF from A. occidentale crude extract. Solvents, strategies and number of materials are displayed to from the crude extracts to the isolation of AGF.

Figure 1.

phytochemical isolation of AGF from A. occidentale crude extract. Solvents, strategies and number of materials are displayed to from the crude extracts to the isolation of AGF.

Figure 2.

Chromatographic profile by UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS (negative ions) (A) and UHPLC-PDA (360 nm) (B) of EtOAc fraction showing its highest peak with retention times of 22.0 min.

Figure 2.

Chromatographic profile by UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS (negative ions) (A) and UHPLC-PDA (360 nm) (B) of EtOAc fraction showing its highest peak with retention times of 22.0 min.

The purification of AGF by CPC was carried out with an initial solvent system selected based on the partition coefficient studies for the major peak. Using the method of areas relationship in UHPLC-PDA, the partition coefficient was determined in all the systems. As can be seen in

table 1 different systems (A and D) were following the rule of 0.5<

K<1.5 where the compound is in the ideal range for separation [

23]. However, systems B, C and E were outside the rule. Then, Solvent A was selected since it had been used for the isolation of AGF from

Ouratea polyantha using Countercurrent Chromatography [

24].

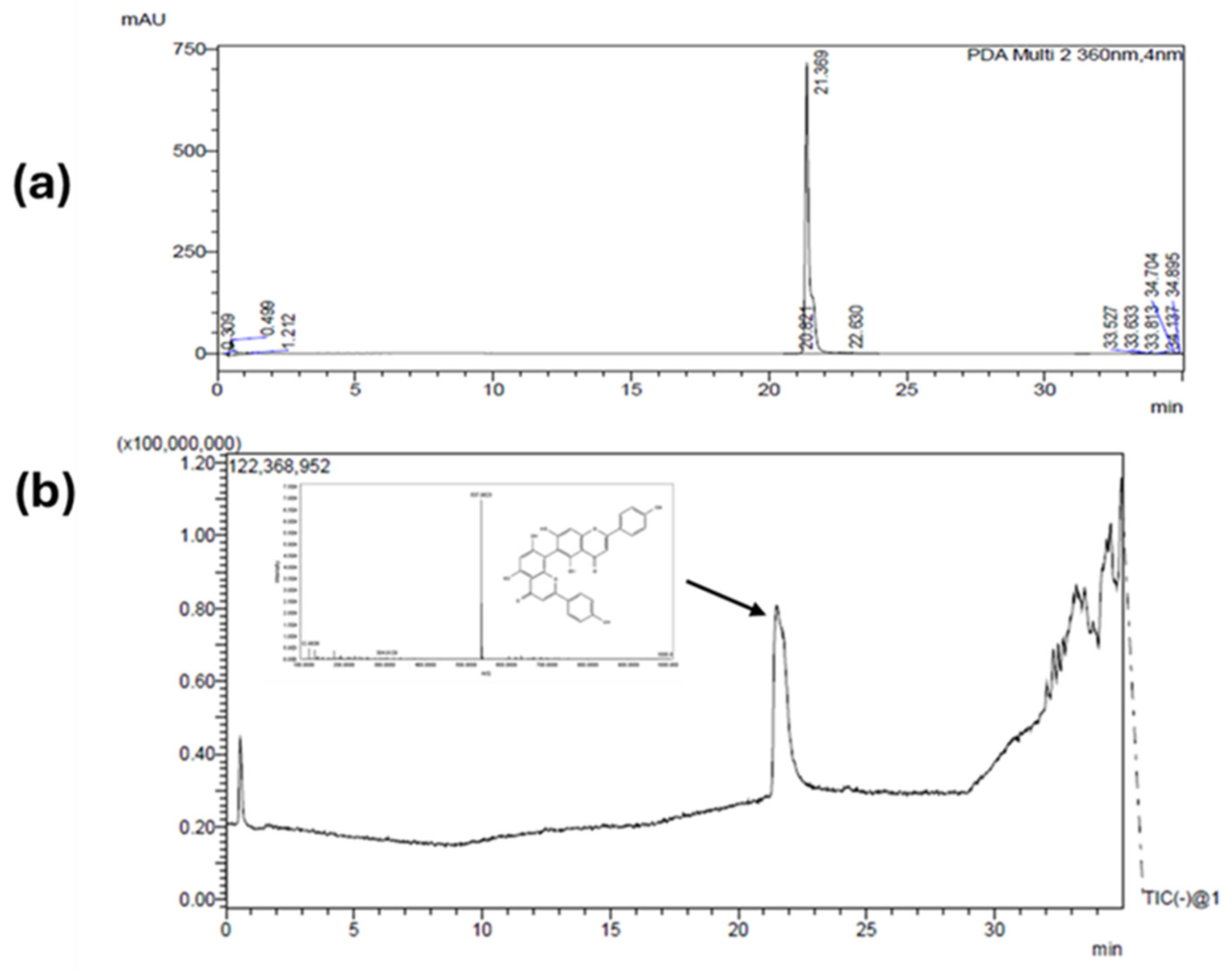

The EtOAc fraction was separated using the CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (4:3.5:2) solvent system, the mobile phase being the lower phase, in descending mode (3), a system previously analyzed and defined from the test tube (K = 0.45, settling time = 16.5 seconds). A flow rate of 5 mL/min was used, with a rotation of 800 rpm. Under these conditions, the retention of the stationary phase was 67%. In a single CPC run, 12.5 mg of the major peak was obtained from the extract, with a purity of over 90%, and it was subsequently identified by UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS as being the biflavone AGF (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Chromatographic analysis of AGF. (A) UHPLC-PDA chromatogram obtained at 360nm. (B) LC-MS chromatogram.

Figure 3.

Chromatographic analysis of AGF. (A) UHPLC-PDA chromatogram obtained at 360nm. (B) LC-MS chromatogram.

AGF is a biflavonoid obtained through the

C-C coupling of two molecules of apigenin [

13] and has been previously reported in

A. occidentale [

25]. In the Chromatograms on Fig 2 and 3, we can see a characteristic peak around 22 minutes corresponding to a mayor compound at 360 nm. Typically, biflavones as well as many flavonoids present high absorption at 330 - 360 nm, therefore this wavelength was used to track this compound during the identification but also during the isolation. Further information about the peak was confirmed by the mass spectrum where the exact mass of 537.0803 [M-H]

- was detected and correlated to AGF.

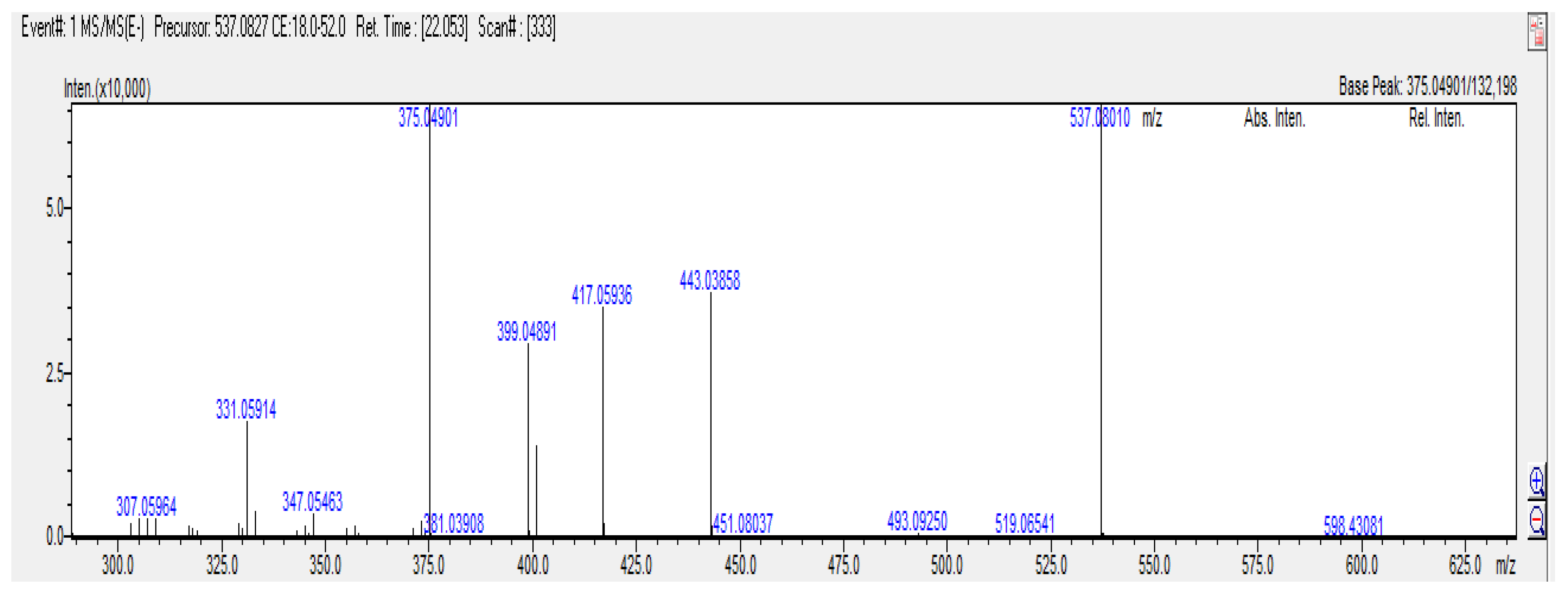

2.2. Fragmentation of Agathisflavone-type biflavonoids

The MS/MS spectrum and fragmentation of agathisflavone are shown in Fig. 4, and their fragmentation pathways are shown in Fig. 5. In general, the most common fragmentation pathways for flavonoids include the loss of H₂O, CO, and C₂H₂O, the retro-Diels–Alder (RDA) reaction, and C-ring fragmentation [

26,

27]. For AGF, the fragmentation mainly occurs through RDA reactions and retrocyclization of one of the flavone units, leading to the characteristic peaks observed.

The negative MS/MS spectrum shows a precursor ion at

m/z 537.0801 [M-H]

- and fragment ions at

m/z 519 [M-H-18]

- corresponding to the loss of H

2O,

m/z 417 [M-H-120]

-, 399 [M-H-H

2O-120]

-, 375 [M-H-H

2O-144]

- corresponding to characteristic Retro-Diels-Alder (RDA) type fragmentation of the ring C for flavone. In general, RDA fragmentation involves the cleavage of two bonds in the C ring, forming negative ions that provide characteristic information. Particularly, these fragment ions contribute to the mass spectral fingerprint of flavones in negative mode [

28,

29]. Additionally, others fragment

m/z 443 [M-H-H

2O-76]

-, 331 [M-H-H

2O-RDA-44]

-, corresponding to the loss of CO and C

2H

8O y CO

2, respectively.

Figure 4.

ESI-MS/MS spectra of Agasthisflavone.

Figure 4.

ESI-MS/MS spectra of Agasthisflavone.

Figure 5.

Proposed fragmentation pathways of agathisflavone.

Figure 5.

Proposed fragmentation pathways of agathisflavone.

2.3. Antifungal potential of AGF

The susceptibility of

Candida spp to the crude extract had already been described in

C. albicans and

C. auris by our laboratory. The MIC value was 62,5 µg/mL [

11]. To determine whether AGF maintained the antifungal activity, the broth microdilution method based on CLSI standard M27-A3 against

C. albicans was performed for the purified compound and the other fractions. The results showed that the fractions and purified AGF were less effective than the crude extract. AGF and the EtOAc fraction presented an MIC of 250 µg/mL, the DCM fraction had an MIC of 125 µg/mL while n-HEX had no activity.

To determine cytotoxicity, a viability test was performed by MTT with J774 macrophages. In general, all fractions were highly toxic compared to the crude extract. In contrast, AGF showed low cytotoxicity with a CC

50 value of 1200 µg/mL, indicating AGF is safe and non-toxic. The selectivity index (SI) was used as a parameter for evaluating the effectiveness of AGF. The SI can be defined as the ratio between the cytotoxic concentration in non-malignant cells and the MIC [

30]. For a natural product or purified compound to be considered promising, it must present an SI value greater than 10 [

31]. The results suggested that despite low toxicity, AGF has low potential to be used as an antifungal as seen in

Table 3.

Our findings are in agreement with Ajileye and collaborators, they carried out the fractionation from a methanolic extract of leaves and it was found that the hexane, DCM and butanol fractions did not inhibit the growth of

C. albicans [

6]. Fractionation is constantly associated with the loss of biological activity against infectious agents. However, Nisa and collaborators obtained hexane and EtOAc fractions from an ethanol extract of leaves that improved the inhibitory activity against

P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis and E. coli [

9]. No antifungal activity has yet been described for fractions of any

A. occidentale extract. This is consistent with our findings on the loss of activity in the hexane, DCM and EtOAc fractions, which presented higher MICS and significant toxicity levels at lower concentrations. Considering the preliminary results, it was decided to evaluate possible interactions between AGF and conventional antifungals since flavonoids have been described as molecules that can establish synergies with antibiotics and antifungals [

32,

33], therefore, checkerboard assay were performed between AGF with the

A. occidentale crude extract (Fig. 6), the DCM fraction, the EtOAc fraction and fluconazole. As shown in

Table 4, increasing the concentration of AGF in the extract or in the EtOAc fraction did not improve the MIC, on the other hand, an additive effect was seen with the DCM fraction. In summary, AGF did not present synergies and highlight the complications of working with compounds isolated from plant extracts, since these are complex mixtures of many substances of different chemical nature responsible for a specific biological activity.

Figure 6.

Checkerboard assay. The concentration range was between 7,9 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL and 15.6 µg/mL to 500 µg/mL for A. occidentale crude extract and AGF, respectively. (red box) wells B9, B10 and B11 were the sterile controls and wells G1, A9, A10 and A11 were untreated growth controls. The FIC I is equal to 2, meaning the effect of the combination of both compounds is indifferent. This figure shows the result of three independent assay.

Figure 6.

Checkerboard assay. The concentration range was between 7,9 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL and 15.6 µg/mL to 500 µg/mL for A. occidentale crude extract and AGF, respectively. (red box) wells B9, B10 and B11 were the sterile controls and wells G1, A9, A10 and A11 were untreated growth controls. The FIC I is equal to 2, meaning the effect of the combination of both compounds is indifferent. This figure shows the result of three independent assay.

These results confirmed that AGF had limited antifungal potential. Interestingly, there is a biflavonide very similar to AGF, composed of two apigenin molecules linked together with the same weight and molecular formula, 537 g/mol and C

30H

18O

10 respectively. However, the bond that makes the C-C coupling is of the 3.8” type and not 6.8” like AGF [

34]. Amentoflavone is mainly extracted from the

Selaginella tamariscina plant [

35].In

C. albicans, it had a fungicidal effect causing mitochondrial dysfunction, cell cycle arrest and finally inducing death by apoptosis [

35,

36]. There are only two works where this compound was identified from an ethanolic extract of

A. occidentale. AGF has been shown to be effective against several strains of influenza A and B viruses [

14], Herpes simplex virus and dengue [

34], and Antitumoral activity in cervical cancer lines [

17] and a powerful neuroprotective [

37]. Due to its low toxicity, it would be important to continue evaluating its biological activity against other infectious agents.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant material and extraction

Leaves of Anacardium occidentale were collected in April 2019, in the municipality of Orito, Putumayo, Colombia (0°3704500 N, 76°5105500 W). Biologist Néstor García from the herbarium of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana carried out the taxonomic determination of the species, and a voucher was deposited with the collection number HPUJ-30548. The plant material was prewashed with 5% hypochlorite and water, dried in an oven with circulating air at 40 °C for 72 h, and then ground in a blade mill.

3.1. Extraction and partitioning of the ethanolic crude extract

The dried and ground plant material was extracted by percolation with EtOH 96% in a ratio of 1:10 (w/v), at room temperature, protected from light in 4 cycles of 24 h each (with solvent changes). The extracts from the different cycles were pooled and concentrated under reduced pressure by rotary evaporation at a temperature of 40 °C. Part of the ethanolic crude extract (7 g) was mixed with 300-500 mg of silica gel, then it was performed a vacuum liquid chromatography. At each partition and in turn partitioned with n-hexane (HEX), dichloromethane (DCM), ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and ethanol:water. This yielded four solvent fractions. The EtOAc and DCM fractions were dried in a rotary evaporator and analysed by HPLC to verify the presence of the presumptive peak for AGF. Then, they underwent separation by CPC.

3.1. Experimental determination of partition coefficients

The selection of the appropriate solvent system for the fractionation of AGF was made by tube test where the sample (2 mg of crude extract) was dissolved in 1 mL of different solvent systems (

Table 1). The

K value was expressed as the peak area of the compound in the stationary organic phase divided by the peak area of the compound in the mobile aqueous phase.

3.1. Purification of AGF by CPC

CPC was carried out using an optimal solvent system composed of chloroform:methanol:water (4:3.5:2, v/v/v) from ethanolic crude extract. The upper solvent phase was used as the stationary phase, and the lower solvent phase was used as the mobile phase for the separation of AGF through the descending mode in an immiscible solvent system. The CPC column of the stationary phase was set to 850 rpm, and the mobile phase was passed through the column at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. 283 mg from EtOAc fraction was dissolved in 10 mL of a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of the two immiscible solvents and injected into the injection valve. The separated fractions were collected using a fraction collector (PLC 2250, Gilson, South Korea), and the process was monitored under 254 - 360 nm ultraviolet (UV) light.

3.1. HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS analysis

UHPLC-ESI-MS-QToF analysis was performed on a Nexera LCMS 9030 Shimadzu Scientific-Instruments® (MD, USA). The stationary phase was a Phenomenex® Kinetex C18 (75 mm x 2.1 mm; 2.6 µm). The mobile phase was performed using 0.1% v/v formic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient of the mobile phase was: 0–8 min., 13% B; 8–12 min., 13–20% B; 12–15 min., 20–22% B; 15–18 min., 22–27% B; 18–20 min., 27–30% B; 20–28 min., 30–35% B; 28–34 min., 35–90% B; 34–35 min., 90–13% B. The flow of the mobile phase was set at 0.4 mL/min. The UV-Vis spectrum was set between 200 and 500 nm, and the chromatograms were recorded at 365 nm. The ionization method was ESI operated in negative ion mode. The capillary potentials were set at +3 kV, drying gas temperature 250 °C, and flow rate of drying gas 350 L/min.

3.1. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against

Candida albicans were detected via the broth microdilution method, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (M27-A3) with some modifications [

38]. ln a 96-well microplate, serial dilutions were made of the AGF, DCM, n-HEX fractions from 3.9 to 500 µg/mL with RPMI 1640 medium (100 µL), then 100 µL of the adjusted inoculum (1-5x10

3 cells/mL) was added, the microplate was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, and afterward a visual and spectrophotometric reading (600 nm) was performed. Controls were used: Fluconazole (FLC) served as a positive control, growth control untreated, and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) without inoculum as a sterile control. Additionally, MIC values for FLC were known previously:

C. albicans ATCC SC5314 (1 µg/mL) [

39]. The MIC was the minimum concentration without visible growth. Absorbance values were taken and considered to be the endpoint value. All assays were performed in triplicate.

3.1. Cytotoxic activity assay

The cytotoxicity of the extract was evaluated on J774 macrophages using MTT colorimetric assay as previously described [

40]. 2.1 × 10

4 cells were cultured in a flat 96-well plate and allowed to adhere and proliferate for 24 hours in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s (DMEM) medium at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. Subsequently, aliquots of AGF (3.9–250 µg/mL) were added to wells containing the adhered cells. The resulting cell cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. After incubation, the medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and 30 μL of MTT at a concentration of 1 mg/mL in PBS was added. The cells were incubated again at 37 °C for 4 h, MTT was removed and 100 μL of DMSO was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the absorbance at 575 nm was measured using a BioTek ELx800 absorbance reader. Incomplete culture medium with 10% MTT was used as a negative control. In addition, cell viability at the half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC

50) was calculated by plotting viability versus log (concentration)

3.1. Checkerboard assay for synergy

To evaluate a possible synergism, the checkerboard test was performed with some adjustments. This is used to determine the type of interaction when combining two compounds with antifungal activity. In brief, AGF with Fluconazole, AGF with

A. occidentale crude extract, and AGF with DCM fraction (final concentrations: 0, 0.06, 0.12, 0.25, 0.50, 1, and 2 times the MIC) were mixed. Then, inoculum (final concentration 1–3×10

3 cells/mL) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, after which time the new MIC was established. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FIC I) is the parameter used in this assay and is determined by a scale of 0 to 4, it is calculated with the following equation: [A/MIC A] + [B/MIC B] = FIC I, where MIC A and MIC B are the MICs of the extract and/or individual antifungal. A and B are the MICs of the same, but in combination. The interaction is considered synergistic with FIC I ≤ 0.5, additive with FIC I > 0.5 – 1, indifferent with FIC I > 1 < 4 or antagonistic FIC I > 4) [

41]

3.1. Statistical analysis

The results of the experiments were tabulated in Excel and analysed through analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test, using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Values of p <0.05 were considered significant.

5. Conclusions

We previously reported the antifungal effect of the ethanolic extract of A. occidentale leaves and wanted to evaluate whether its major flavonoid was responsible for its activity. In the present study, we purify AGF from crude ethanol extract of leaves of Anacardium occidentale by a CPC analysis in a single run. CPC was a powerful, fast and practical tool for the purification of compounds from plant extracts. AGF was found to inhibit the growth of C. albicans at 250 µg/ml and did not establish synergies when combining with the fractions of the A. occidentale extract.

Author Contributions

L.F.Q.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, data curation, original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. D.F.A.: methodology, data curation, writing—review, and editing. L.C.C.: methodology, data curation. G.M.C.: investigation, supervision, data curation, resources, project administration, and original draft preparation. C.M.P.G.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, supervision, formal analysis, resources and original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, MinCiencias, Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo e ICETEX, and Convocatoria Ecosistema Científico—Colombia Científico “Generación de alternativas terapéuticas en cáncer a partir de plantas a través de procesos de investigación y desarrollo transnacional, articulados en sistemas de valor sostenibles ambiental y económicamente” sponsor by World Bank (contract No. FP44842-221-2018) and convocatoria del Fondo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación del Sistema General de Regalías, en el marco del Programa de Becas de Excelencia Doctoral del Bicentenario, definido en el artículo 45 de la ley 1942 de 2018, Bogotá, Colombia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, MinCiencias, Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo e ICETEX, and Convocatoria Ecosistema Científico - Colombia Científico “Generación de alternativas terapéuticas en cáncer a partir de plantas a través de procesos de investigación y desarrollo transnacional, articulados en sistemas de valor sostenibles ambiental y económicamente” sponsored by the World Bank (contract No. FP44842-221-2018). We also thank the Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Colombia for allowing the use of genetic resources and products derived (Contract number 212/2018; Resolution 210/2020). Finally to Convocatoria del Fondo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación del Sistema General de Regalías, en el marco del Programa de Becas de Excelencia Doctoral del Bicentenario, definido en el artículo 45 de la ley 1942 de 2018, Bogotá, Colombia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baptista, A.; Gonçalves, R.V.; Bressan, J.; Gouveia, C. Review Article Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Crude Extracts and Fractions of Cashew (Anacardium Occidentale L.), Cajui (Anacardium Microcarpum), and Pequi (Caryocar Brasiliense C.): A Systematic Review. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Royo, V.D.A.; Mercadante-simões, M.O.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Oliveira, D.A. De; Aguiar, M.M.R.; Costa, E.R.; Ferreira, P.R.B. Anatomy, Histochemistry and Antifungal Activity of Anacardium humile (Anacardiaceae ) Leaf. 2015, 1549–1561. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, R.; Liberio, S.A.; Amaral, F.M.M.; Raquel, F.; Maria, L.; Torres, B.; Neto, V.M.; Nassar, R.; Guerra, M.; Luis, S. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Anacardium Occidentale L. Flowers in Comparison to Bark and Leaves Extracts. 2016, 87–99. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Gültekin-özgüven, M.; Kırkın, C.; Özçelik, B.; Morais-braga, M.F.B.; Nalyda, J.; Carneiro, P.; Bezerra, C.F.; Gonçalves, T.; Douglas, H.; et al. Anacardium Plants: Chemical, Nutritional Composition and Biotechnological Applications. 2019, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Duangjan, C.; Rangsinth, P.; Zhang, S.; Wink, M.; Paola, R. Di Anacardium Occidentale L. Leaf Extracts Protect Against Glutamate/H2O2 -Induced Oxidative Toxicity and Induce Neurite Outgrowth: The Involvement of SIRT1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Teneurin 4 Transmembrane Protein. 2021, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ajileye, O.O.; Obuotor, E.M.; Akinkunmi, E.O.; Aderogba, M.A. Isolation and Characterization of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Compounds from Anacardium Occidentale L. (Anacardiaceae) Leaf Extract. J King Saud Univ Sci 2015, 27, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.; José Weverton Almeida-Bezerra; Gonçalves da Silva, T.; Pereira, P.S.; Fernanda de Oliveira Borba, E.; Braga, A.L.; Alencar Fonseca, V.J.; Almeida de Menezes, S.; Henrique da Silva, F.S.; Augusta de Sousa Fernandes, P.; et al. Phytochemical Profile and Anti-Candida and Cytotoxic Potential of Anacardium Occidentale L. (Cashew Tree). Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2021, 37, 102192. [CrossRef]

- Chodankar, R.N.; Patil, R.; Hogade, S.A.; Patil, A.G.; Acharya, A. Evaluation of Mangifera indica, Anacardium occidentale Leaf Extracts and 0.2% Chlorhexidine Gluconate on Disinfection of Maxillofacial Silicone Material Surface Contaminated with Microorganisms - An In vitro Study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2024, 14, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisa, K.; Hasanah, A.U.; Damayanti, E.; Frediansyah, A.; Anwar, M.; Khumaira, A.; Anindita, N.S. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity and Phytochemical Profiling of Indonesian Anacardium occidentale L. Leaf Extract and Fractions. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res 2024, 12, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.; José Weverton Almeida-Bezerra; Gonçalves da Silva, T.; Pereira, P.S.; Fernanda de Oliveira Borba, E.; Braga, A.L.; Alencar Fonseca, V.J.; Almeida de Menezes, S.; Henrique da Silva, F.S.; Augusta de Sousa Fernandes, P.; et al. Phytochemical Profile and Anti-Candida and Cytotoxic Potential of Anacardium occidentale L. (Cashew Tree). Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2021, 37, 102192. [CrossRef]

- Quejada, L.F.; Hernandez, A.X.; Chitiva, L.C.; Bravo-Chaucanés, C.P.; Vargas-Casanova, Y.; Faria, R.X.; Costa, G.M.; Parra-Giraldo, C.M. Unmasking the Antifungal Activity of Anacardium occidentale Leaf Extract against Candida albicans. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.S.; Tan, M.L.; Ooi, K.L.; Sulaiman, S.F. The Effect of Flavonols in Anacardium occidentale L. Leaf Extracts on Skin Pathogenic Microorganisms. Nat Prod Res 2023, 37, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayiha Ba Njock, G.; Bartholomeusz, T.A.; Foroozandeh, M.; Pegnyemb, D.E.; Christen, P.; Jeannerat, D. NASCA-HMBC, a New NMR Methodology for the Resolution of Severely Overlapping Signals: Application to the Study of Agathisflavone. Phytochemical Analysis 2012, 23, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, C.S.; Rocha, M.E.N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Marttorelli, A.; Ferreira, A.C.; Rocha, N.; de Oliveira, A.C.; de Oliveira Gomes, A.M.; dos Santos, P.S.; da Silva, E.O.; et al. Agathisflavone, a Biflavonoid from Anacardium occidentale L., Inhibits Influenza Virus Neuraminidase. Curr Top Med Chem 2020, 20, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, I.; Campos, C.; Medeiros, R.; Cerqueira, F. Antimicrobial Activity of Dimeric Flavonoids. Compounds 2024, 4, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, G.; El-Nashar, H.A.S.; Mostafa, N.M.; Eldahshan, O.A.; Boiangiu, R.S.; Todirascu-Ciornea, E.; Hritcu, L.; Singab, A.N.B. Agathisflavone Isolated from Schinus polygamus (Cav.) Cabrera Leaves Prevents Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment and Brain Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Phytomedicine 2019, 58, 152889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taiwo, B.J.; Fatokun, A.A.; Olubiyi, O.O.; Bamigboye-Taiwo, O.T.; van Heerden, F.R.; Wright, C.W. Identification of Compounds with Cytotoxic Activity from the Leaf of the Nigerian Medicinal Plant, Anacardium occidentale L. (Anacardiaceae). Bioorg Med Chem 2017, 25, 2327–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.; David, J. Methods For Extraction And Isolation Of Agathisflavone From Poincianella pyramidalis. Quim Nova 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-J.; Pei, L.-X.; Wang, K.-B.; Sun, Y.-S.; Wang, J.-M.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Gao, M.-L.; Ji, B.-Y. Preparative Isolation of Two Prenylated Biflavonoids from the Roots and Rhizomes of Sinopodophyllum emodi by Sephadex LH-20 Column and High-Speed Counter-Current Chromatography. Molecules 2015, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destandau, E.; Boukhris, M.A.; Zubrzycki, S.; Akssira, M.; Rhaffari, L. El; Elfakir, C. Centrifugal Partition Chromatography Elution Gradient for Isolation of Sesquiterpene Lactones and Flavonoids from Anvillea radiata. Journal of Chromatography B 2015, 985, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagnoleau, J.-B.; Rocha, I.L.; Khedher, R.; Coutinho, J.A.; Michel, T.; Fernandez, X.; Papaiconomou, N. Separation of Natural Compounds Using Eutectic Solvent-Based Biphasic Systems and Centrifugal Partition Chromatography. J Chromatogr A 2023, 1691, 463812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.C. dos; da Silva, A.F.; Castro, R.N.; Leitão, G.G. Selective Isolation of Artepillin C from Brazilian Green Propolis by Countercurrent Chromatography. J Chromatogr A 2025, 1752, 465977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, A.; Hostettmann, K. Developments in the Application of Counter-Current Chromatography to Plant Analysis. J Chromatogr A 2006, 1112, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J.; Rodríguez, M.; Hasegawa, M.; González-Mujica, F.; Duque, S.; Ito, Y. (6R,9S)-6"-(4"-Hydroxybenzoyl)-Roseoside, a New Megastigmane Derivative from Ouratea polyantha and Its Effect on Hepatic Glucose-6-Phosphatase. Nat Prod Commun 2012, 7, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar Galvão, W.R.; Braz Filho, R.; Canuto, K.M.; Ribeiro, P.R. V; Campos, A.R.; Moreira, A.C.O.M.; Silva, S.O.; Mesquita Filho, F.A.; S.A.A.R., S.; Melo Junior, J.M.A.; et al. Gastroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Activities Integrated to Chemical Composition of Myracrodruon Urundeuva Allemão - A Conservationist Proposal for the Species. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 222, 177–189. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yao, S.; Zhang, X.-X.; Song, H. Rapid Screening and Structural Characterization of Antioxidants from the Extract of Selaginella doederleinii Hieron with DPPH-UPLC-Q-TOF/MS Method. Int J Anal Chem 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, L.; Shi, Y. Structural Characterization and Identification of Biflavones in Selaginella tamariscina by Liquid Chromatography-diode-array Detection/Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2011, 25, 2173–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, H.; Belhadj, S.; Jlail, L.; El Feki, A.; Sayadi, S.; Allouche, N. LC–MS–MS and GC–MS Analyses of Biologically Active Extracts of Tunisian Fenugreek (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum L.) Seeds. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2018, 12, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M.; Anusiewicz, I.; Skurski, P. The Mechanism of a Retro-Diels–Alder Fragmentation of Luteolin: Theoretical Studies Supported by Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry Results. Molecules 2022, 27, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indrayanto, G.; Putra, G.S.; Suhud, F. Validation of In-Vitro Bioassay Methods: Application in Herbal Drug Research. In; 2021; pp. 273–307.

- Awouafack, M.D.; McGaw, L.J.; Gottfried, S.; Mbouangouere, R.; Tane, P.; Spiteller, M.; Eloff, J.N. Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity of the Ethanol Extract, Fractions and Eight Compounds Isolated from Eriosema robustum (Fabaceae). BMC Complement Altern Med 2013, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, E.H.; Garcia Cortez, D.A.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Nakamura, C.V.; Dias Filho, B.P. Potent Antifungal Activity of Extracts and Pure Compound Isolated from Pomegranate Peels and Synergism with Fluconazole against Candida albicans. Res Microbiol 2010, 161, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Shao, X.; Di, X.; Cui, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y. In Vitro Synergy of Polymyxins with Other Antibiotics for Acinetobacter baumannii: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015, 45, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J.C.J.M.D.S.; Campos, V.R. Natural Biflavonoids as Potential Therapeutic Agents against Microbial Diseases. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 769, 145168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Park, K.; Lee, I.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Yeo, S.-H.; Woo, E.-R.; Lee, D.G. S-Phase Accumulation of Candida albicans by Anticandidal Effect of Amentoflavone Isolated from Selaginella Tamariscina. Biol Pharm Bull 2007, 30, 1969–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.; Lee, J.; Jin, H.-G.; Woo, E.-R.; Lee, D.G. Amentoflavone Stimulates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Induces Apoptotic Cell Death in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 2012, 173, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velagapudi, R.; Ajileye, O.O.; Okorji, U.; Jain, P.; Aderogba, M.A.; Olajide, O.A. Agathisflavone Isolated from Anacardium occidentale Suppresses SIRT1-mediated Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia and Neurotoxicity in APPSwe-transfected SH-SY5Y Cells. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 32, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reference Method for Broth Dilution. 2008.

- Vargas-Casanova, Y.; Carlos Villamil Poveda, J.; Jenny Rivera-Monroy, Z.; Ceballos Garzón, A.; Fierro-Medina, R.; Le Pape, P.; Eduardo García-Castañeda, J.; Marcela Parra Giraldo, C. Palindromic Peptide LfcinB (21-25)Pal Exhibited Antifungal Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Candida. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 7236–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Y.J.; Quejada, L.F.; Villamil, J.C.; Baena, Y.; Parra-Giraldo, C.M.; Perez, L.D. Development of Amphotericin B Micellar Formulations Based on Copolymers of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) and Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Conjugated with Retinol. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Casanova, Y.; Bravo-Chaucanés, C.; Martínez, A.; Costa, G.; Contreras-Herrera, J.; Medina, R.; Rivera-Monroy, Z.; García-Castañeda, J.; Parra-Giraldo, C. Combining the Peptide RWQWRWQWR and an Ethanolic Extract of Bidens pilosa Enhances the Activity against Sensitive and Resistant Candida albicans and C. auris Strains. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Settling time and partition coefficient of AGF present of Anacardium occidentale.

Table 1.

Settling time and partition coefficient of AGF present of Anacardium occidentale.

| Code |

Solvente System |

Settling Time |

Partition Coefficient of Major peak |

|

A |

CHCL3:MeOH:H2O |

16.5 |

0.45 |

|

B |

HEX: EtOAc:MeOH:H2O |

20 |

0.235 |

|

C |

HEX: EtOAc:MeOH:H2O |

14.5 |

0.14 |

|

D |

HEX: EtOAc:MeOH:H2O |

19 |

1.14 |

|

E |

CH2CL2:MEOH:H20 |

70 |

1.59 |

Table 3.

Evaluation of the antifungal potential of AGF and fractions of A. occidentale.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the antifungal potential of AGF and fractions of A. occidentale.

| Compounds |

MIC |

CC50

|

SI |

| n-HEX |

1000 µg/mL |

65 µg/mL |

0,06 |

| DCM |

125 µg/mL |

56 µg/mL |

0,45 |

| EtOAc |

250 µg/mL |

80 µg/mL |

0,32 |

| AGF |

250 µg/mL |

1200 µg/mL |

4,8 |

Table 4.

Fractional inhibitory concentration index of AGF and other compouds.

Table 4.

Fractional inhibitory concentration index of AGF and other compouds.

| Compound |

MIC (µg/mL) |

FIC |

Interpretation |

| Alone |

Combination |

FIC |

FIC I |

| Agathisflavone |

250 |

125 |

0.5 |

1,5 |

Indifference |

| EtOAC fraction |

250 |

250 |

1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| A.occidentale |

62,5 |

62.5 |

1 |

2 |

Indifference |

| Agathisflavone |

250 |

250 |

1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Agathisflavone |

250 |

125 |

0.5 |

1 |

Additive |

| DCM fraction |

125 |

62,5 |

0,5 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Agathisflavone |

250 |

250 |

1 |

5 |

Antagonism |

| Fluconazole |

1 |

4 |

4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).