1. Introduction

Progression of metastatic ovarian cancer mainly occurs within the peritoneal cavity, where malignant cells can exfoliate from the surface of the growing tumour at a primary site with the movement of peritoneal fluid [

1,

2]. Malignant ovarian cancer cells often form small clusters and aggregates that facilitate metastatic growth. These cell clusters pose significant clinical challenges because they are less likely to respond to treatment. As a result, they can survive, giving rise to drug-resistant clones that thrive within the peritoneal cavity. These clones become the primary source of metastatic growth, as they adhere to the surface of the peritoneal walls. The first step in the successful establishment of secondary tumours is the adhesion of ovarian cancer cell clusters and aggregates to the peritoneal membrane, which consists of a single layer of mesothelial cells covering internal organs [

3,

4]. This initial interaction between cancer cells and the mesothelial lining is critical and believed to be essential for the successful implantation of cancer cells.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to describe the adherence of ovarian cancer cells to the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the mesothelial cell lining. These mechanisms include cancer cell-mediated CD44 binding to a hyaluronan on the surface of mesothelial cells, cancer cell-mediated apoptotic-cell death of the mesothelial cells via the TNF-alpha mediated pathway, and the retraction of the mesothelial cell lining by components in the ascitic fluid [

5,

6,

7]. All of these mechanisms would cause ECM to become exposure beneath the mesothelial cell lining, leading to the cancer cells’ initial binding to collagens [

8,

9]. Ovarian cancer cells express many integrin subunits that specially bind to laminins, and to collagens I and IV; the primary ECM is present underneath the mesothelial lining [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Integrins are the plasma membrane proteins with extracellular and intracellular domains and are heterodimeric structures composed of alpha and beta subunits with the beta subunits regulating the functions of integrins [

14,

15]. Upon ECM binding, the beta subunits can convert mechanical contacts into cellular signalling information via the activation of numerous signalling proteins responsible for tumour progression [

16]. Among the integrin subunits, the β4 subunit is known to be involved in the tumorigenic steps of cancers [

17,

18]. However, the role of the β4 subunit in the early adhesion of ovarian cancer cell clusters remains relatively unknown. The β4 subunit is a well-known protein that partners with integrins and receptor tyrosine kinases, such as EGFR, HER-2, and c-Met [

19,

20]. Collectively, inhibiting the synergistic interaction between integrins and receptor tyrosine kinases could provide a novel approach to preventing the initial adhesion of cancer cells to the peritoneal wall, potentially reducing the progression of advanced ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer cells and tissue express varying levels of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET, and the overexpression of these receptors has been associated with poor patient prognosis [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Although inhibitors targeting these receptors, either as monotherapies, or in combination, have been evaluated in both preclinical and clinical settings, the outcomes have been inconsistent [

21,

26,

27]. It is important to note that targeting these pathways in the late stages of ovarian cancer, where extensive tumour dissemination has already occurred, may not be scientifically rational or clinically effective [

28]. However, intervening at earlier stages, specifically by blocking the adhesion of disseminated ovarian cancer cells to the peritoneal cavity, could represent a more effective strategy to control tumour progression.

Thus, we hypothesise that the adhesion of ovarian cancer cell clusters to the ECM is dependent on the co-activation of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET in conjunction with the β4 subunit. Therefore, the use of specific inhibitors to block these receptor tyrosine kinases could disrupt ovarian cancer cells via the β4 subunit adhesion-dependent to the ECM.

3. Discussion

Advanced ovarian cancer often spreads via the peritoneum, leading to the establishment of multiple secondary tumour nodules of varying sizes. Although the advanced stage is treatable with surgery and chemotherapy, recurrence is common, and tumours often become resistant to treatment. Identifying the early stages of cell adhesion to the peritoneal membrane’s surface is crucial to minimising the potential for tumour implantation within the peritoneal cavity and the regrowth of tumour cells [

31,

32]. The initial contact between ovarian cancer cells, whether as single cells, small clusters, or compact spheroids, and the peritoneal membrane is crucial for successful implantation. This can occur in several ways. Cancer cells may disrupt the interaction between mesothelial cell layers and the underlying basement membrane proteins, exposing these proteins and allowing cancer cells to adhere [

33,

34]. Additionally, in advanced stages, the unique microenvironment created by the ascitic fluid can compromise the integrity of the mesothelial cell monolayer, making the basement membrane proteins more accessible to cancer cells [

10,

35].

The interaction between these proteins and cancer cells is crucial for the homing and growth of cancer cells within the peritoneal cavity. This occurs when integrins on ovarian cancer cells bind to specific motifs on the ECM. The mutual binding of these interactions triggers a cascade of events that orchestrate protein complexes at the focal adhesion sites, recruiting specific proteins that allow cancer cells to survive and spread, provided the conditions are favourable. Integrins, particularly the β4 integrin subunit, is essential for the survival and migration of cancer cells [

36]. The co-activation of β4 subunits is facilitated by various growth factor receptors, including EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET, although this co-dependence is also cell-line specific [

16,

17,

37].

This study investigated the effect of growth factors (EGF and HGF) on the adhesion of ovarian cancer cell lines to the ECM, comprising collagen I, collagen IV and laminins (GelTrex™). The growth factors EGF and HGF are present in ascitic fluid from advanced ovarian cancer patients, which typically contains a complex mixture of growth factors, small molecules, and lipids [

38,

39,

40]. It also includes ECM produced by both normal and ovarian cancer cells [

41,

42]. The concentrations of growth factors, including EGF and HGF, vary among patients’ ascites [

38,

43]. Thus, the mitogenic properties of these growth factors on cell adhesion are the central focus of this study.

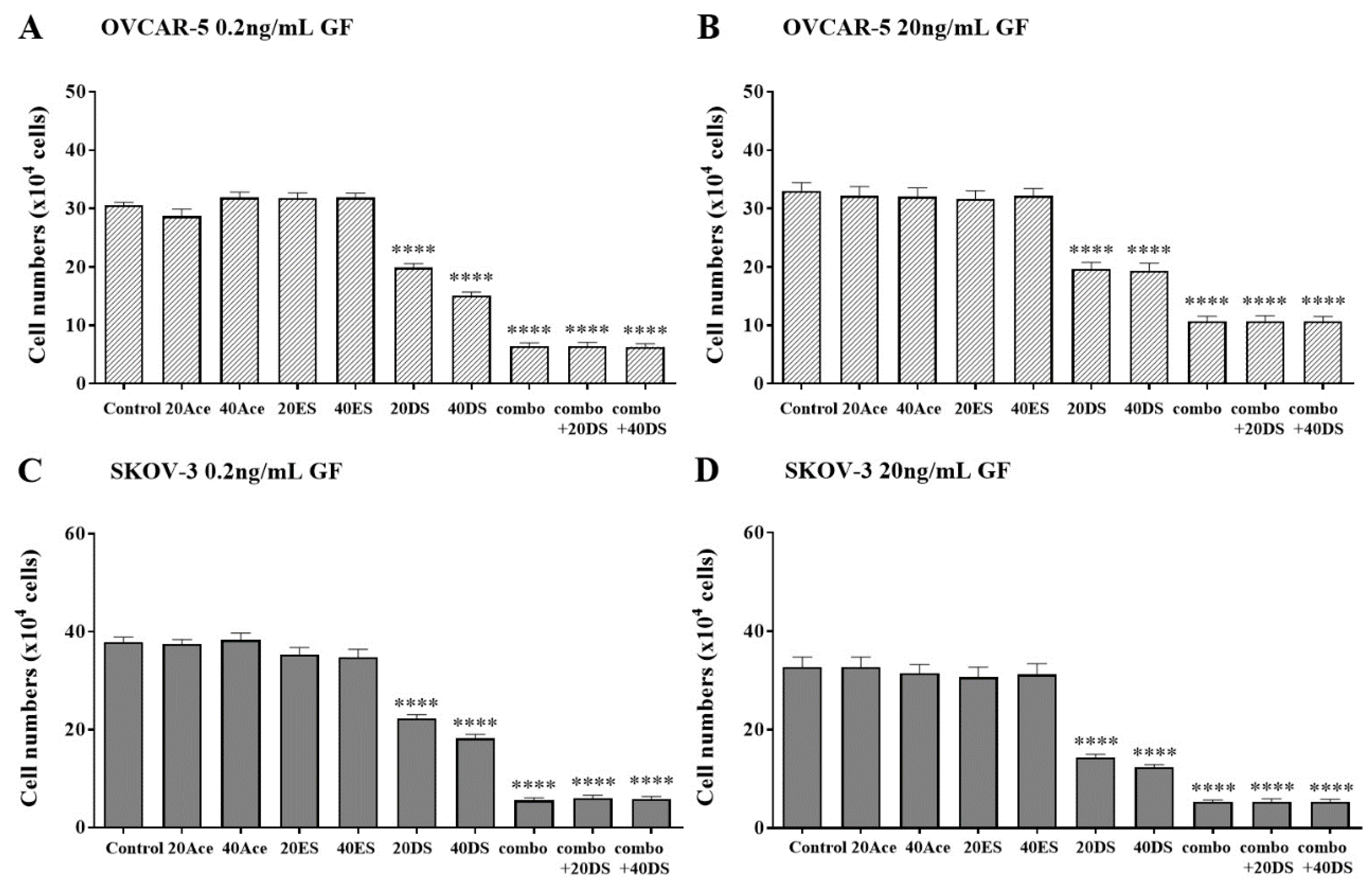

The effects of the EGFR/HER-2 inhibitor canertinib and the c-MET inhibitor PHA665752 on cell adhesion were evaluated. In EGFR- and c-MET-positive ovarian cancer cells such as OVCAR-5, adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) was more pronounced at supra-physiological concentrations of the growth factors (20 ng/mL) compared to physiological levels. Similarly, in SKOV-3 cells, which express EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET, cell adhesion was enhanced at both physiological and supra-physiological concentrations. In both cell lines, canertinib inhibited growth factor-induced adhesion in a concentration-dependent manner. Likewise, PHA665752 reduced cell adhesion in a dose-dependent fashion. These findings suggest that EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET contribute to ECM-mediated adhesion in ovarian cancer cells. Notably, combined treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 led to a greater reduction in cell adhesion than with either inhibitor alone, indicating that the cooperative activity of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET may be important for adhesion. The inhibitors were applied four hours prior to cell adhesion assays in ovarian cancer cell clusters, ensuring that the observed effects were not influenced by changes in cell proliferation.

Several previous studies have investigated the effects of growth factors and inhibitors on cell monolayers, particularly focusing on the invasion and migration behaviour of ovarian cancer cells [

44,

45,

46]. However, a study by Parashar et al. demonstrated that co-activation of EGFR and HER-2 in OVCAR-4 and OVCAR-5 cell clusters is critical for cell survival and spheroid formation. This activation occurs in cells with lower expression of specific integrin subunits, including integrin β1, αV, and α5, compared to their adherent counterparts [

47].

The central question in our study is how do growth factors such as EGF and HGF, along with their respective inhibitors, regulate the adhesion of ovarian cancer cell clusters, given that EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET do not directly interact with the extracellular matrix (ECM). We hypothesise that ovarian cancer cell clusters utilise integrin proteins on the cell surface to mediate adhesion, potentially through co-interactions with EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET. Previous studies have demonstrated the expression of various integrin subunits in cell monolayers and ovarian cancer tissues [

14,

34,

48]. However, only a limited number of studies have investigated the presence and functional role of integrins in the adhesion processes of ovarian cancer cell clusters or spheroids [

49]. Moreover, the binding of ovarian cancer cells to the ECM appears to be substrate-dependent, suggesting that specific integrin use may be uniquely tailored to the adhesive requirements of ovarian cancer cells [

50].

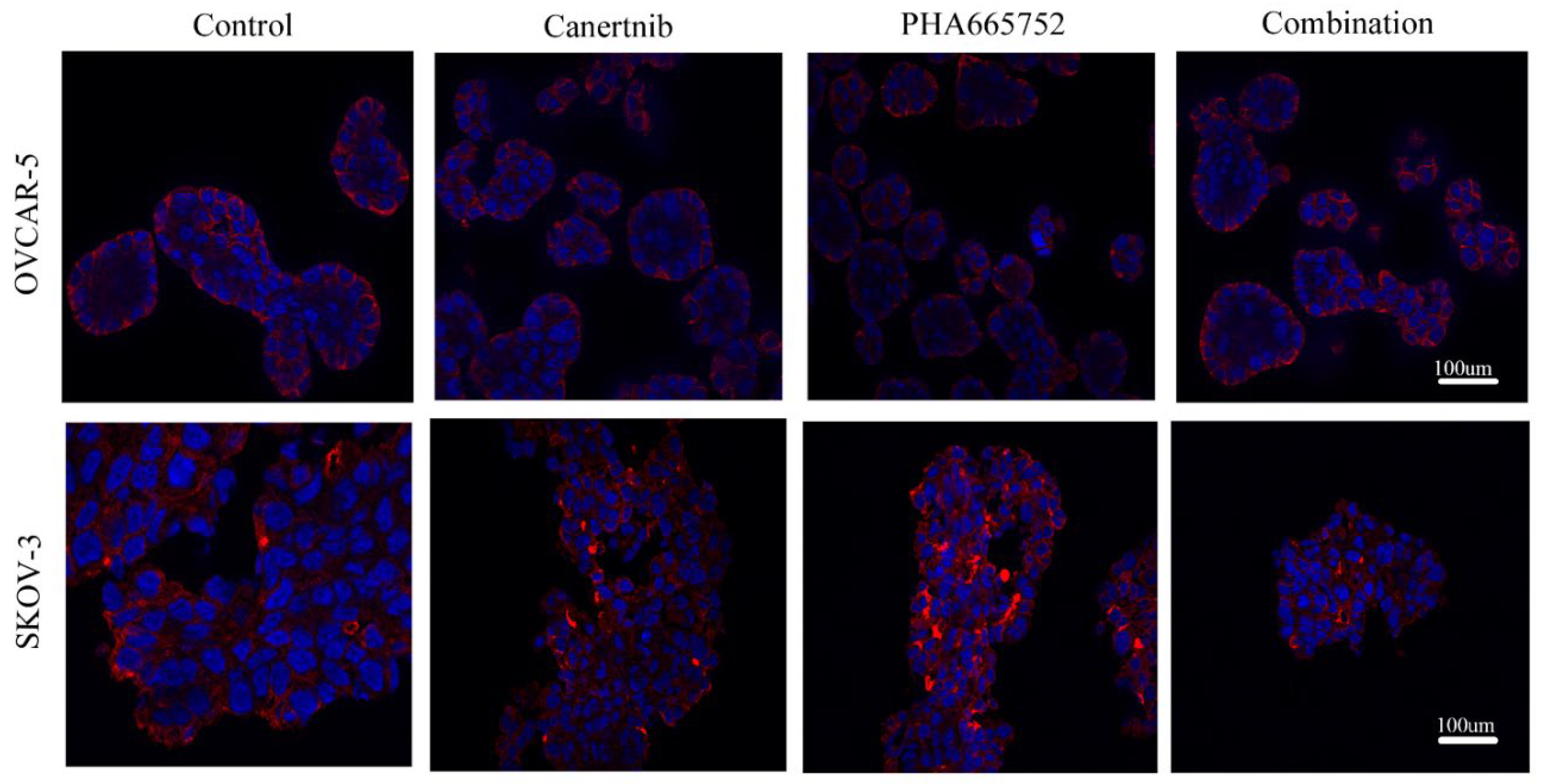

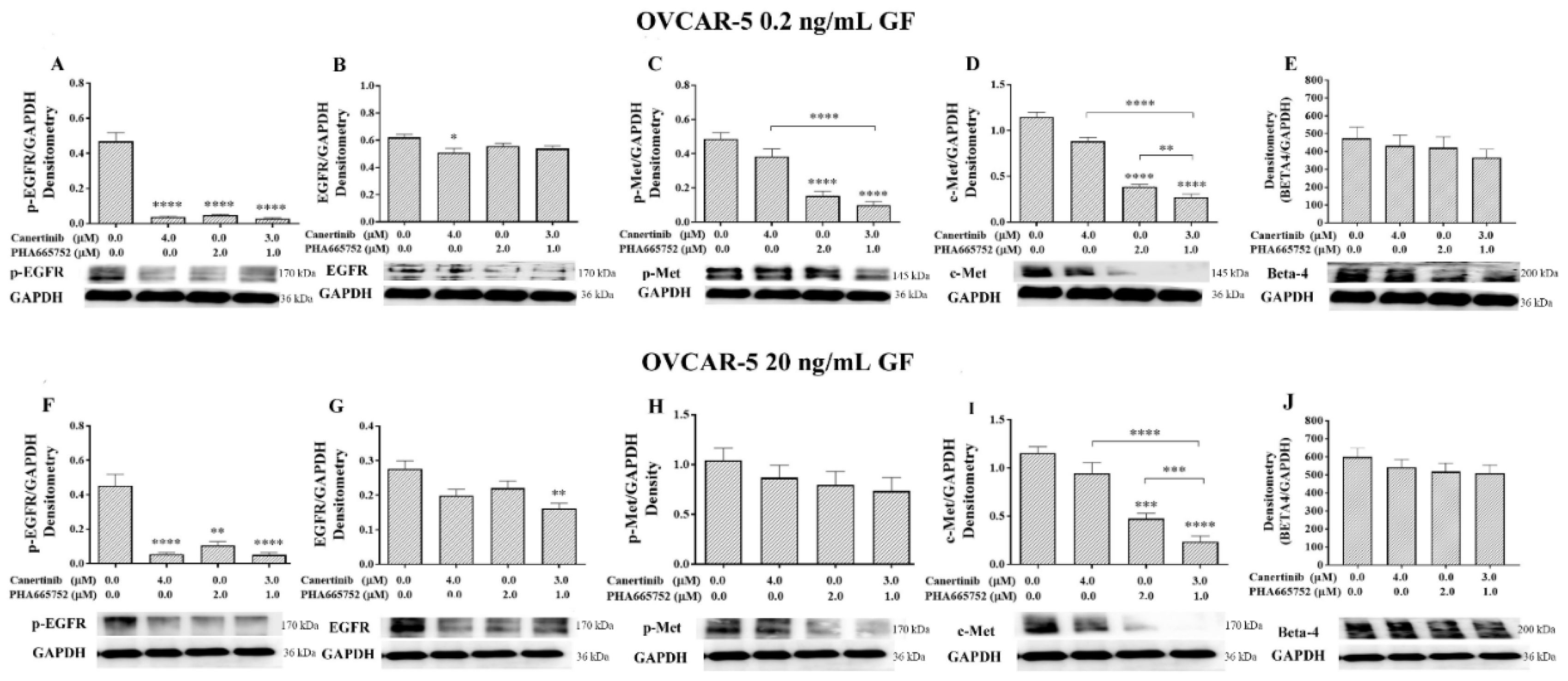

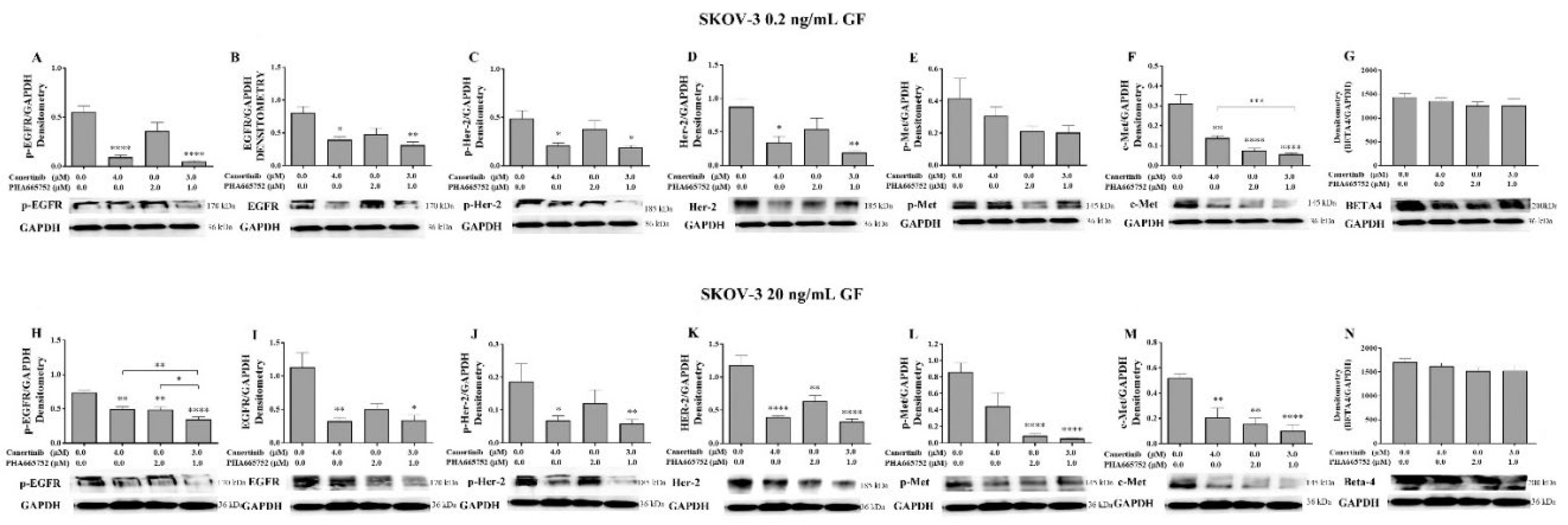

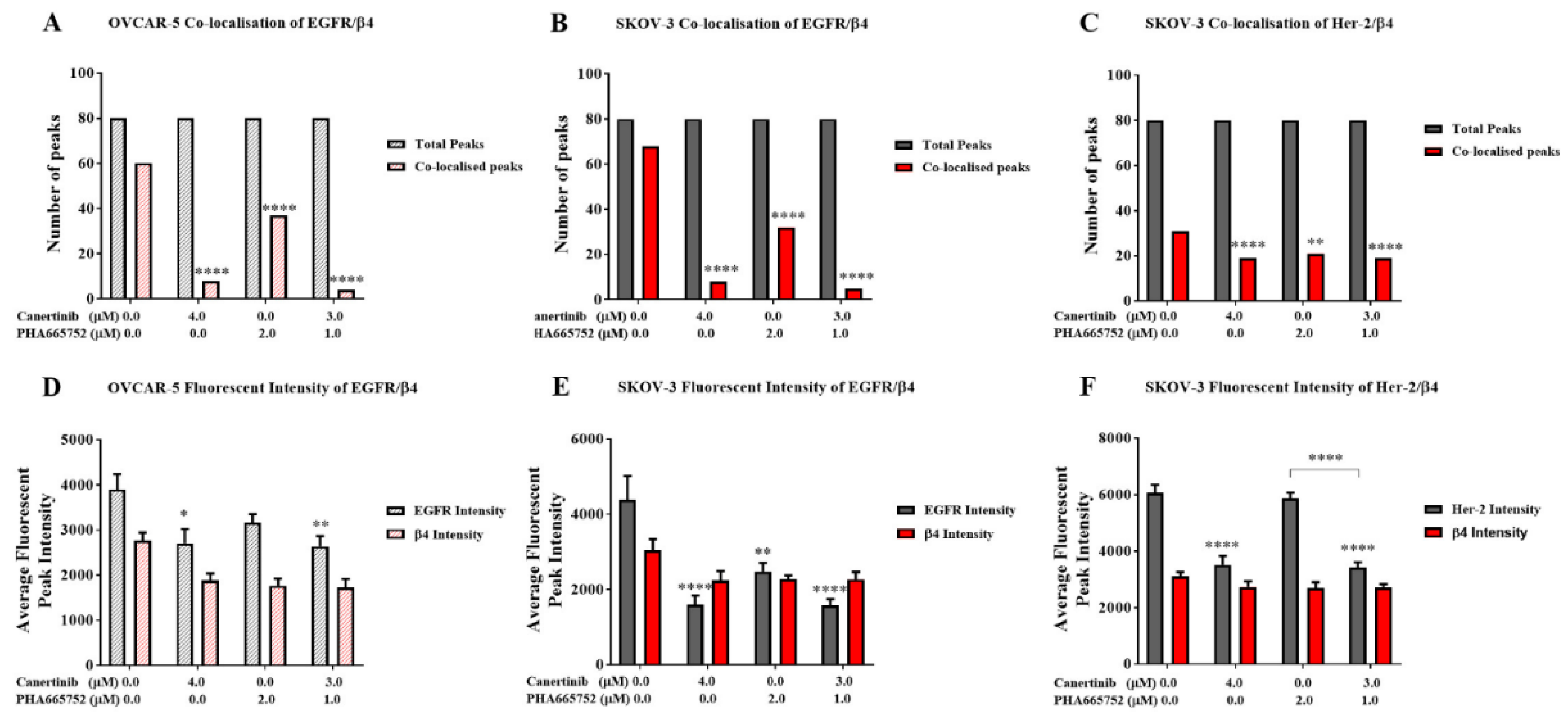

One intriguing aspect of our findings is that when RGDS amino acids (

Figure 5), which mimic a binding site of β1 integrin, were used, they significantly reduced cell adhesion of OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3. However, the combination of both drugs with or without RGDS was more potent than RGDS alone. These results suggest that, although the direct interaction between cells and the ECM via RGDS-integrin-mediated processes reduces adhesion, the indirect interaction of integrins via non-RGDS binding is also crucial for cell adhesion. We suspect that β4 integrin might play a key role in this adhesion process, as the β4 integrin subunit does not bind to the RGDS amino acid sequences [

51]. Additionally, we postulate that inhibitors of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET may disrupt the protein–protein interactions between these receptor tyrosine kinases and the β4 integrin subunit. Notably, the total levels of the β4 integrin subunit remained unchanged, as shown by immunostaining (Figs. 7, 8, and 9), suggesting that the observed effects are not due to changes in protein expression, but may involve alternative regulatory mechanisms. However, phosphorylation of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET in OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells (Figs. 7 and 8) was reduced following treatment with the inhibitors, highlighting a potential co-dependent relationship between integrin β4 and the phosphorylation status of these receptor tyrosine kinases. We further postulate that the interaction between the β4 integrin and these receptor tyrosine kinases occurs at the physical level to facilitate the early stages of cell adhesion. Intriguingly, we observed that drug treatment disrupted the co-localisation of β4 integrin with the receptor tyrosine kinases (Figs. 9A–C), underscoring the importance of protein–protein interactions between these molecules in maintaining cellular adhesion dynamics. It has been suggested that the cytoplasmic domain of the β4 integrin plays a critical role in interacting with the cytoplasmic domains of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET. This raises the possibility that the tyrosine kinase inhibitors canertinib and PHA665752, which bind to the ATP-binding sites within the cytoplasmic domains of these receptors, may disrupt their protein–protein interactions with β4 integrin. Such disruption could represent a potential mechanism by which these inhibitors reduce cell adhesion to the ECM [

52,

53].

Numerous previous studies have demonstrated an association between β4 integrin and EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET; however, evidence supporting their interaction specifically in ovarian cancer models remains limited. Furthermore, the signalling pathways including PI-3K/AKT, FAK and MAPK/ERK activated by the binding of integrin β4 to these receptor tyrosine kinases have been well-characterized in monolayer cultures of various cancer types [

16,

54,

55,

56]. Our study did not investigate downstream signalling cascades, as we focused specifically on the early adhesion of ovarian cancer cells through the physical interactions of EGFR, HER-2, and c-MET with the β4 integrin. Further research should explore the impact of combining antibodies that specifically target the extracellular domain of the β4 integrin subunit, either alone or in combination with these tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Such studies could reveal synergistic inhibitory effects that may have clinical relevance. These novel drug combinations may be particularly beneficial for a subset of ovarian cancer patients whose tumours are positive for EGFR, HER-2, c-MET, and β4 integrin.

This study has some limitations. First, incorporating molecular techniques to delete the extracellular domain of β4 integrin would strengthen our hypothesis regarding the requirement of β4 integrin interaction for cell adhesion via EGFR/HER-2/c-MET axis. Second, applying Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) could provide direct evidence at the cellular level to support the interaction between β4 integrin and these tyrosine kinase receptors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 were obtained from Dr Judith McKenzie, Haematology Research Group, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand. OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells were maintained in DMEM media (GIBCO”, Life Technologies, New Zealand) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO”, Life Technologies, New Zealand), Pen/Strep (GIBCO”, Life Technologies, New Zealand) at a working concentration of 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutaMAX™ (GIBCO”, Life Technologies, New Zealand) and 1 µg/mL Fungizone (Life Technologies, New Zealand). The final concentration of glucose in the media was 5.5 mM. The respective supplemented media is hereafter referred to as working media. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Each cell line, SKOV-3 and OVCAR-5, was authenticated using STR testing by CellBank (Children’s Medical Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia).

4.2. Generating 3D Cell Clusters

A 12 mg/mL poly-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (poly- HEMA) solution was prepared by mixing 1.2 g of poly-HEMA with 100 mL of 95% ethanol. The solution was heated to 72°C with continued stirring until fully dissolved. To generating the 3D cell clusters and aggregates, each cell culture plate was pre-coated with 300 µL of 12 mg/mL of (poly-HEMA) (Sigma, Auckland, New Zealand). The poly-HEMA was warmed at 70 ºC before application. The coated plates were allowed to dry overnight on an orbital shaker at 37°C and then were stored at room temperature until use. Before using the poly-HEMA coated plate, the plate was washed once with 1xPBS.

Confluent cells were incubated for 20 min with 1x trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher, Auckland, New Zealand) to detach them from the culture flask. Once the cells were separated, they were collected and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded, and cell pellets were re-suspended in the working media. A cell count was performed using a haemocytometer to calculate the volume of cell suspension needed to obtain 1x105 cells/mL in each well of poly-HEMA coated 24 well plates.

4.3. Adhesion Assays of Ovarian Cancer Cell Clusters

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Auckland, New Zealand). Cells were cultured as 3D cell clusters/aggregates for six days in a working medium before further incubation for 24 h in a serum-free medium (SFM). Cells were then treated with SFM supplemented with 0.2 or 20 ng/mL growth factors and canertinib, PHA665752, RGDS, RGES alone or combined with these inhibitors for four hours before performing the cell adhesion assay. Cells with conditioned media were then transferred onto a freshly pre-coated collagen-gel matrix (a mixture of 2 mg/mL collagen I and 25% (v/v) GelTrex™, Thermo Fisher, New Zealand) cell culture wells and the cells were incubated for an additional four hours in a CO2 incubator at 37ᵒC. After that, cellular metabolism was determined by the Alamar Blue dye assay. In addition, the numbers of adherent and non-adherent cells were counted by a haemocytometer.

4.4. Determination of Protein Expression Using a Western Blotting

After treatment, cells were then washed with ice-cold 1x PBS, and lysed using either radio-immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer, RIPA (made up with 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 tablet protease inhibitor), or 0.1% SDS ( 0.1% SDS dissolved in 1x PBS ), or modified 0.1% SDS buffer (0.1% SDS, 1XPBS, 10% Glycerol, 5mM EDTA, cocktail of phosphatase and protease inhibitors). Cells were mixed and left on ice for 30 min. Cellular components were fractionated by centrifugation at 6700 g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred into new Eppendorf tubes before determining the protein concentration of each sample using a Micro-BCATM Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Following the determination of the protein concentrations, the total protein lysates of 10 µg were denatured by boiling with 0.2% v/v of Laemmli 5x sample buffer (0.2% (v/v) bromophenol blue, 25% (v/v) glycerol, and 14.4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol in Tris-HCl pH 6.8), for 10 min. All samples were left on ice for 30 min before being loaded into sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels that were 1 mm thick. SDS-PAGE gels consist of 5% stacking gel and 10% separating gel were used to separate protein components. The SDS-PAGE was run for 2.5 h at 120 Volts. Once protein bands were separated, proteins were electro-blotted onto Poly Vinyl PVDF membrane (Immun-Blot®PVDF Bio-Rad, New Zealand) for 15-30 minutes using a BIO-RAD Trans-Blot® TurboTM Transfer system (Bio-Rad, New Zealand. The PVDF membranes were incubated with methanol for 5 minutes before washing with MilliQ water and soaking with the transfer sponges in freshly made transfer buffer (0.19% Tris, 0.9% glycine dissolved in MilliQ water) at least 15 minutes before the transfer. Primary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). The antibodies that were used were anti- EGFR (SC-03), pEGFR (SC-101668), HER-2 (SC-284), pHER-2 (SC-12352-R), c-MET (SC-10), p-MET (SC-101736), GAPDH (SC-25778) and β4 integrin (SC-9090) respectively.

Membranes were then blocked with the specified blocking solutions, 5% skim milk or 1-4% BSA, dissolved in Tris-buffered Tween saline (TBS-T). Blocking was carried out for one h before incubation with the primary antibody solutions overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Primary antibodies were diluted at a range of 1:500, 1:1000 or 1:2000 with 50% (v/v) of TBS-T and the appropriate blocking buffer. Next, the membranes were washed with TBS-T four times for 10 min each wash before adding the secondary antibody and incubating at room temperature for 90 min on an orbital shaker followed by washing with TBS-T four times for 10 min each wash. Secondary antibodies (anti-mouse HRP and anti-Rabbit HRP, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) were diluted 1:5000 or 1:10000 with 50% (v/v) TBS-T and the specified blocker. Membranes were developed using a Clarity™ Western ECL Blotting Substrates detection kit (Bio-Rad, New Zealand). Protein bands were visualised and densitometry analysis was performed using Alliance 4.7, Unitec software (Cambridge, UK). Densitometry readings were based on median bands from raw data images and normalised against the band intensity of GAPDH as a reference protein.

4.5. Detection of Cellular Proteins Using Immunofluorescence

OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells were cultured to generate cell clusters and aggregates for six days. Cell clusters and aggregates were collected and fixed with 50% (v/v) acetone/methanol solution ice-cold. OVCAR-5 cell clusters were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, pH 7.4 and re-suspended in 200 µl cold PBS. The clusters were then transferred on poly-lysine coated microscope slides, left to dry at 37°C for 20 min before proceeding with the main procedure. Before frozen sectioning, SKOV-3 aggregates were washed with PBS pH 7.4 and stained with 1% aniline blue dye solution (Sigma-Aldrich LTD, New Zealand) for 15 min. The aniline blue dye binds to proteins on cell aggregates and makes aggregates more visible when a frozen section is cut. Cells were washed two times with ice-cold 1x PBS before they were embedded in a liquid CryO-Z-T solution, OCT (Ted Pella Inc., USA). The liquid OCT blocks were frozen at -80°C for at least 24 h. Seven µm thick slices were cut from the block of frozen OCT using a CM186UV Cryostat (Lieca BIOSYSTEM, Deutschland) and were placed on an appropriately labelled Superfrost plus slides (Menzel-Glaser, Germany). Two cut sections were collected per slide. There were six slides per sample in total, and the slides were stored at -20°C until analysis. Both cell lines were blocked with 4% BSA in 1x PBS for one h at room temperature before incubation overnight with a 1:200 dilution of primary antibody at 4°C. Next day, the slides were washed twice with constant stirring in a large washing jar with 100 mL ice cold PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min each time and further incubated with a 1:500 dilution of secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with FITC for 60 minutes in a 37°C incubator.

The secondary antibody solution was removed and 500 µL of 10 µg/mL of (4`, 6-diamido-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Thermo fisher NZ), a fluorescent dye that binds to DNA, was added to the cells and left for 20 min in the dark. The slides were then washed twice with constant stirring in a large washing jar for 10 min each time with 100 mL ice cold 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS pH 7.4. Then cells were mounted with ice cold anti-fading solution (2 mg/mL p-phenylenediamine in 80% glycerol, pH 7.8). Fluorescent images were captured using an epifluorescence microscope with a 40x/1.3 N.A. oil/DIC objective lens (AxioVision 4.5. Apotome software, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

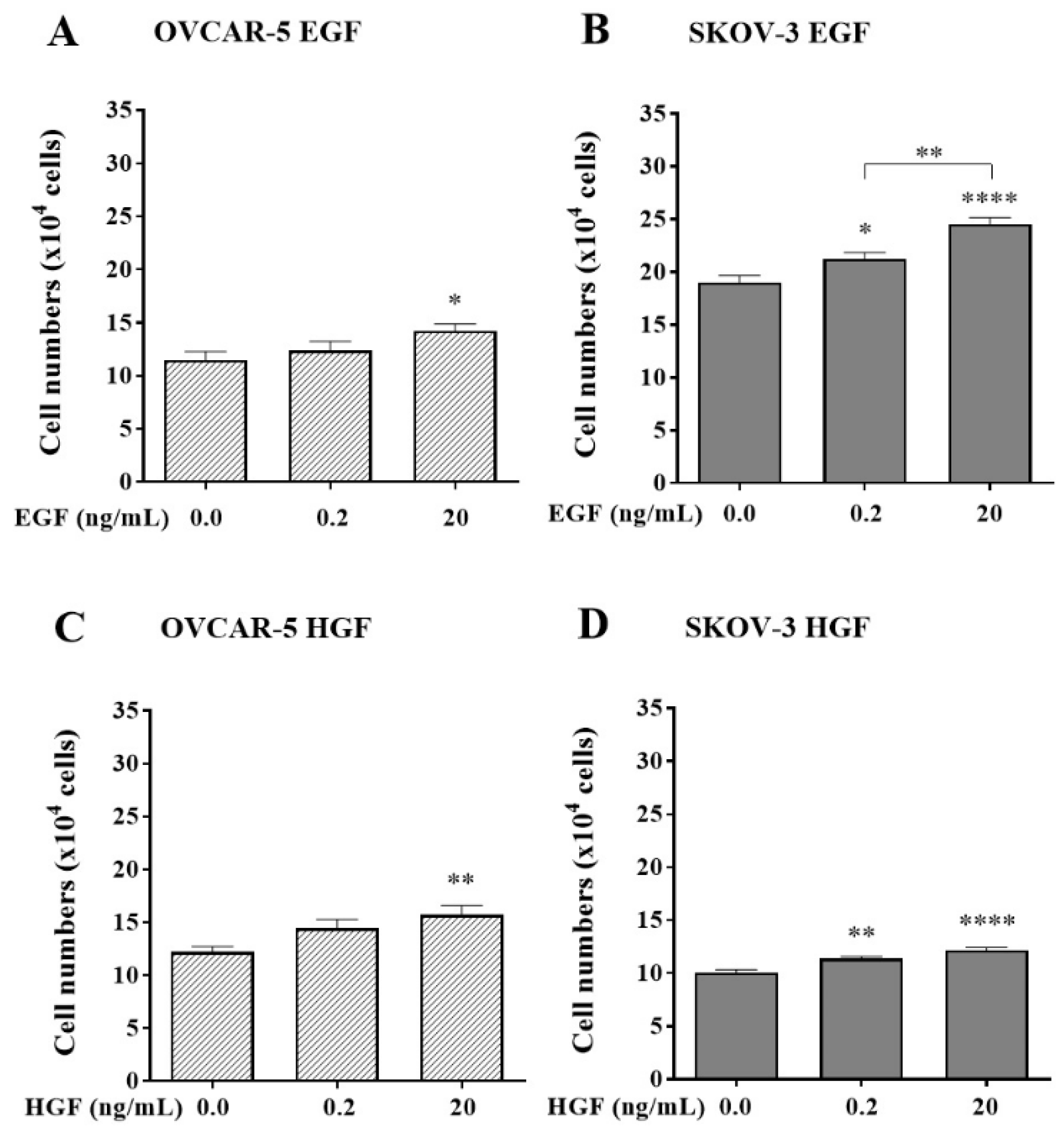

Figure 1.

Effects of EGF and HGF on the adhesion of the OVCAR-5 (A, C) and SKOV-3 (B, D) ovarian cancer cell lines. Numbers represent the number of adherent OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates treated with 0.2 and 20 ng/mL of EGF or HGF respectively. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell numbers are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 1.

Effects of EGF and HGF on the adhesion of the OVCAR-5 (A, C) and SKOV-3 (B, D) ovarian cancer cell lines. Numbers represent the number of adherent OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates treated with 0.2 and 20 ng/mL of EGF or HGF respectively. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell numbers are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

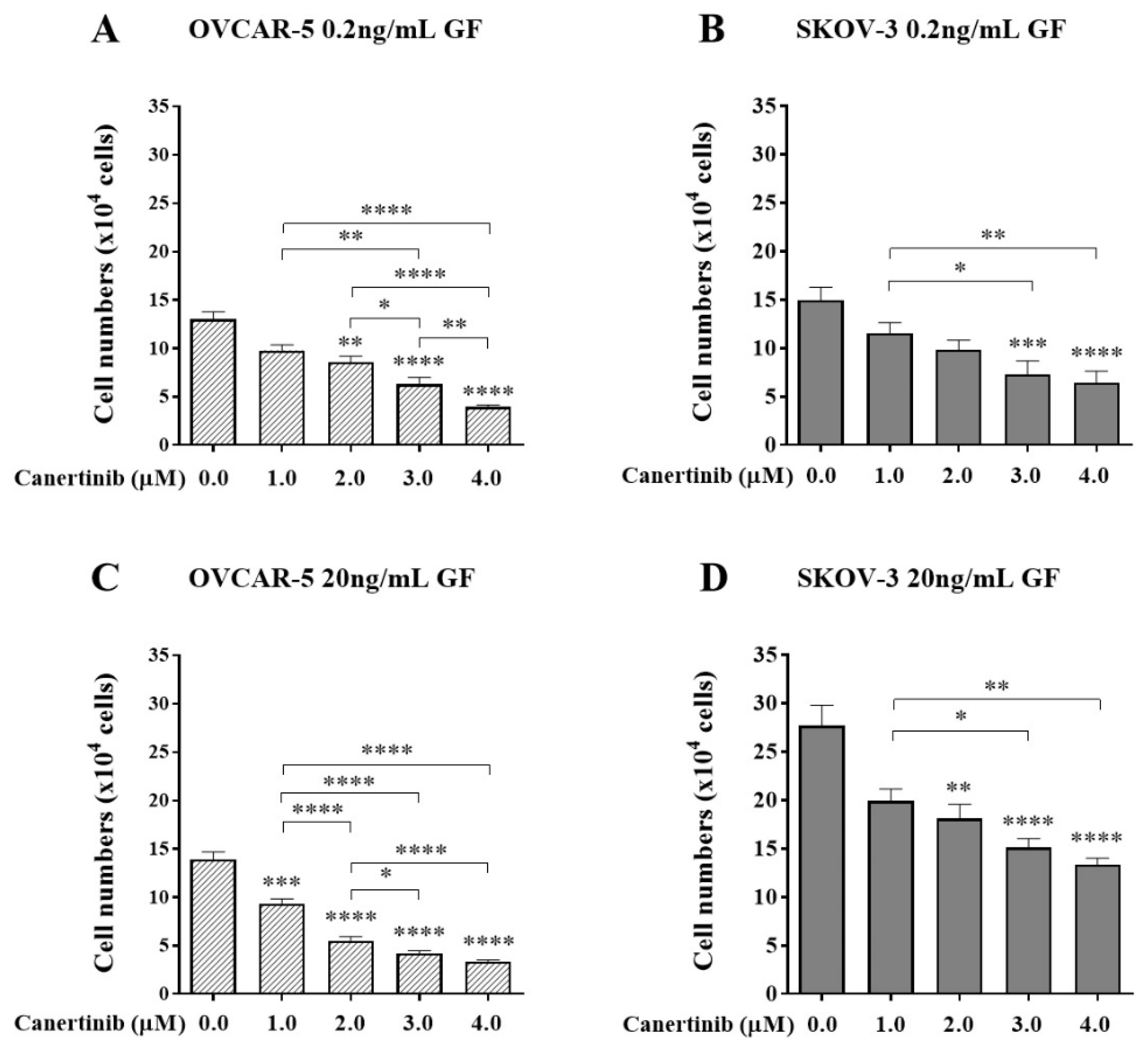

Figure 2.

The effect of canertinib on cell adhesion of OVCAR-5 clusters (A, C) and SKOV- 3 aggregates (B, D) in the presence of growth factors (GF). Cells were treated with canertinib in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL EGF+HGF (GF) for four hr before a further four hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 2.

The effect of canertinib on cell adhesion of OVCAR-5 clusters (A, C) and SKOV- 3 aggregates (B, D) in the presence of growth factors (GF). Cells were treated with canertinib in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL EGF+HGF (GF) for four hr before a further four hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

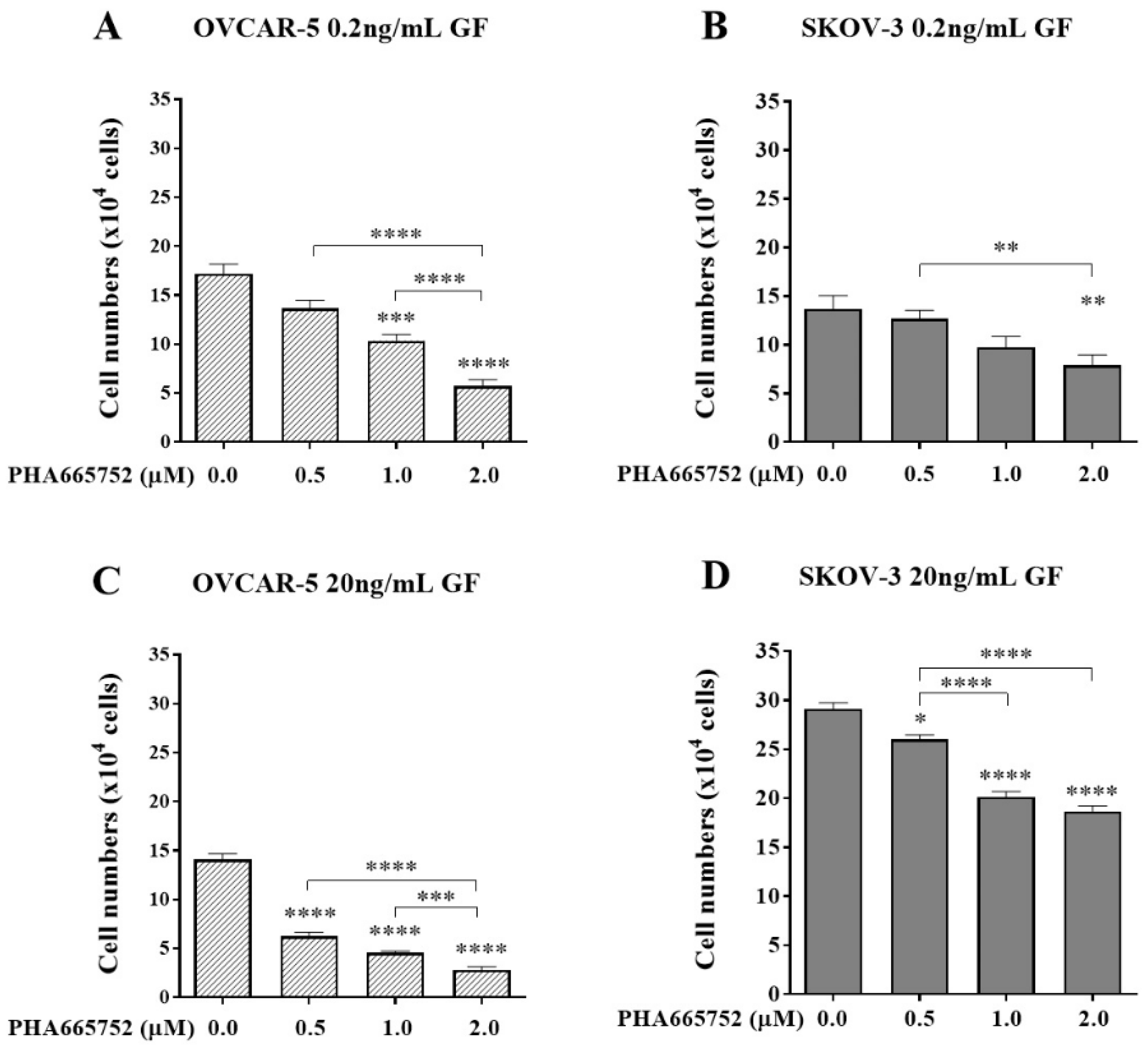

Figure 3.

The effect of PHA665752 on cell adhesion of OVCAR-5 clusters (A, C) and SKOV-3 aggregates (B, D) in the presence of growth factors (GF). Cells were treated with PHA665752 in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL EGF+HGF (GF) for four hr before a further four hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 3.

The effect of PHA665752 on cell adhesion of OVCAR-5 clusters (A, C) and SKOV-3 aggregates (B, D) in the presence of growth factors (GF). Cells were treated with PHA665752 in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL EGF+HGF (GF) for four hr before a further four hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

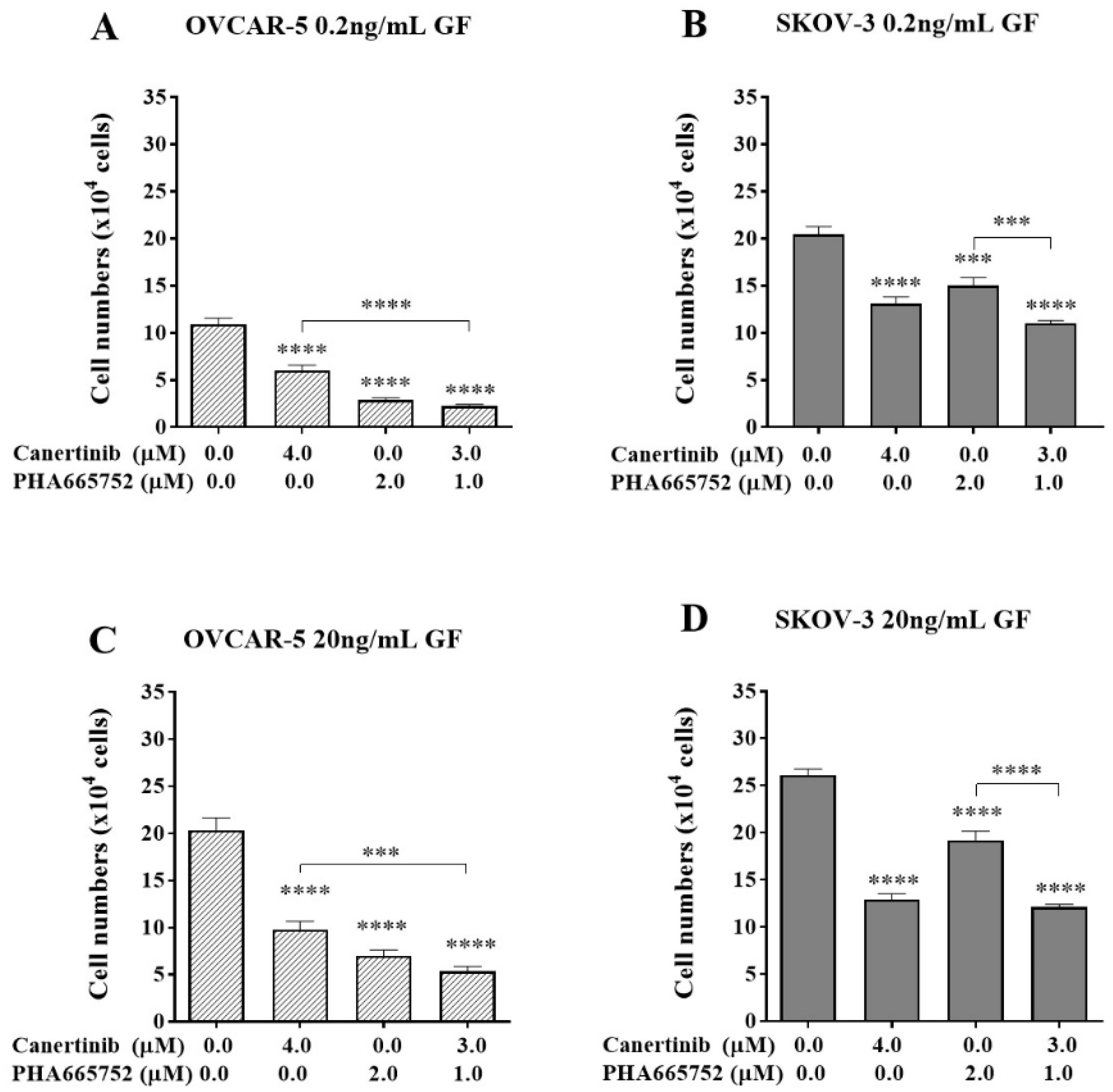

Figure 4.

The effect of a combination of canertinib and PHA665752 on the adherence of OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates. Cells were treated with canertinib alone or a combination of canertinib and PHA665752 in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL GF for four hr before a further 4 hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 4.

The effect of a combination of canertinib and PHA665752 on the adherence of OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates. Cells were treated with canertinib alone or a combination of canertinib and PHA665752 in the presence of 0.2 or 20 ng/mL GF for four hr before a further 4 hr exposure during the adhesion assay. Adherent cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 5.

The effect of an exogenous RGDS peptide on cell adhesion in the presence of canertinib and PHA665752. OVCAR-5 (A, B) and SKOV-3 (C, D) clusters were treated with 0.2 ng/mL (A, C) and 20 ng/mL (B, D) of GF in the presence of inhibitors including 20 or 40µM of acetate (Ace), RGES (ES), RGDS (DS), and a mixture of 3µM canertinib+1µM PHA665752 (combo). Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 5.

The effect of an exogenous RGDS peptide on cell adhesion in the presence of canertinib and PHA665752. OVCAR-5 (A, B) and SKOV-3 (C, D) clusters were treated with 0.2 ng/mL (A, C) and 20 ng/mL (B, D) of GF in the presence of inhibitors including 20 or 40µM of acetate (Ace), RGES (ES), RGDS (DS), and a mixture of 3µM canertinib+1µM PHA665752 (combo). Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. (n=3). Statistically significant differences in cell number are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), and p<0.0001 (****) compared to the control or other concentrations.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent images of the β4 integrin (red) and DNA (blue) of OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates after cells were treated by 3µM canertinib, 1µM PHA665752 and their combination. Cells were treated with inhibitors for four hr before conducting immunofluorescence.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent images of the β4 integrin (red) and DNA (blue) of OVCAR-5 clusters and SKOV-3 aggregates after cells were treated by 3µM canertinib, 1µM PHA665752 and their combination. Cells were treated with inhibitors for four hr before conducting immunofluorescence.

Figure 7.

Western blotting and densitometry indices of selective proteins from OVCAR-5 cell clusters after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in the presence of 0.2 (A, B, C, D, E) and 20 (F, G, H, I, J) ng/mL GF. The levels of p-EGFR (A, F), EGFR (B, G), p-MET (C, H), MET (D, I) and β4 integrin subunit (E, J) are representative of densitometry indices as mean ± SEM (n=9). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations. GAPDH was used as a house keeping protein.

Figure 7.

Western blotting and densitometry indices of selective proteins from OVCAR-5 cell clusters after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in the presence of 0.2 (A, B, C, D, E) and 20 (F, G, H, I, J) ng/mL GF. The levels of p-EGFR (A, F), EGFR (B, G), p-MET (C, H), MET (D, I) and β4 integrin subunit (E, J) are representative of densitometry indices as mean ± SEM (n=9). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations. GAPDH was used as a house keeping protein.

Figure 8.

Western blotting and densitometry indices of selective proteins of SKOV-3 cell clusters after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in the presence of 0.2 (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and 20 (H, I, J, K, L, M, N) ng/mL GF. The levels of p-EGFR (A, H), EGFR (B, I), p-HER-2 (C, J), HER-2 (D, K), p-MET (E, L), MET (F, M) and β4 integrin subunit (G, N) are representative of densitometry indices as mean ± SEM (n=9). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations. GAPDH is used as a house keeping protein.

Figure 8.

Western blotting and densitometry indices of selective proteins of SKOV-3 cell clusters after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in the presence of 0.2 (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and 20 (H, I, J, K, L, M, N) ng/mL GF. The levels of p-EGFR (A, H), EGFR (B, I), p-HER-2 (C, J), HER-2 (D, K), p-MET (E, L), MET (F, M) and β4 integrin subunit (G, N) are representative of densitometry indices as mean ± SEM (n=9). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations. GAPDH is used as a house keeping protein.

Figure 9.

Co-localisation and total fluorescent intensity of EGFR, HER-2 and β4 in OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in 20ng/mL GF. The co-localisation of EGFR/β4 in OVCAR-5 (A) and its total fluorescent intensity (D), co-localisation of EGFR/β4 in SKOV3 (B) and its total fluorescent intensity (E), co-localisation of HER-2/β4 in SKOV-3 (C), and its total fluorescent intensity (F). The total fluorescent intensity (peaks) of 80 (n=3) were randomly counted and pool to generate graphs (A, B, C). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations.

Figure 9.

Co-localisation and total fluorescent intensity of EGFR, HER-2 and β4 in OVCAR-5 and SKOV-3 cells after treatment with canertinib and PHA665752 alone and in combination in 20ng/mL GF. The co-localisation of EGFR/β4 in OVCAR-5 (A) and its total fluorescent intensity (D), co-localisation of EGFR/β4 in SKOV3 (B) and its total fluorescent intensity (E), co-localisation of HER-2/β4 in SKOV-3 (C), and its total fluorescent intensity (F). The total fluorescent intensity (peaks) of 80 (n=3) were randomly counted and pool to generate graphs (A, B, C). Statistically significant differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***), and p<0.0001(****) compared to the control or the other concentrations.