Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

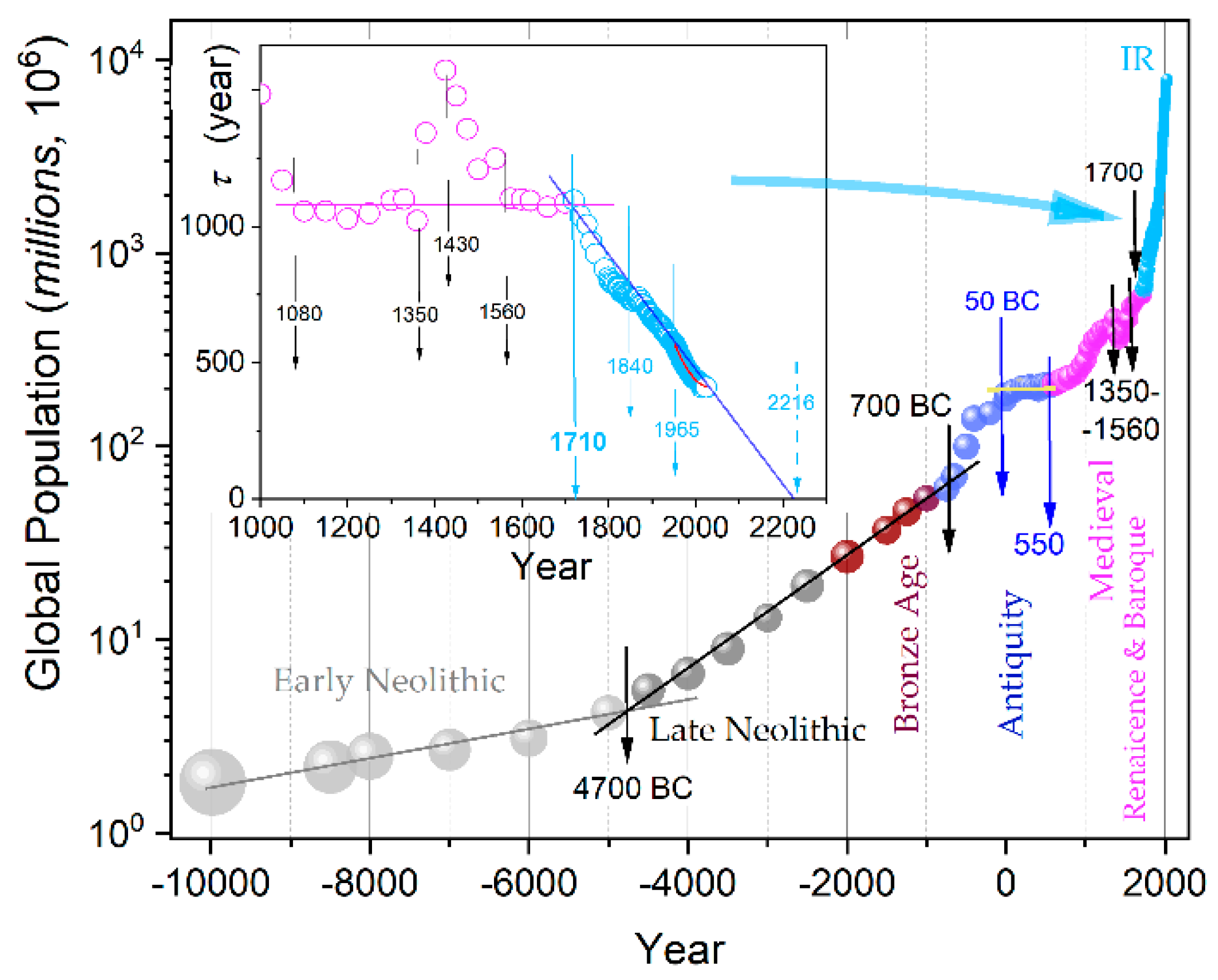

3.1. Global Population, Carrying Capacity, and Condorcet Criterion

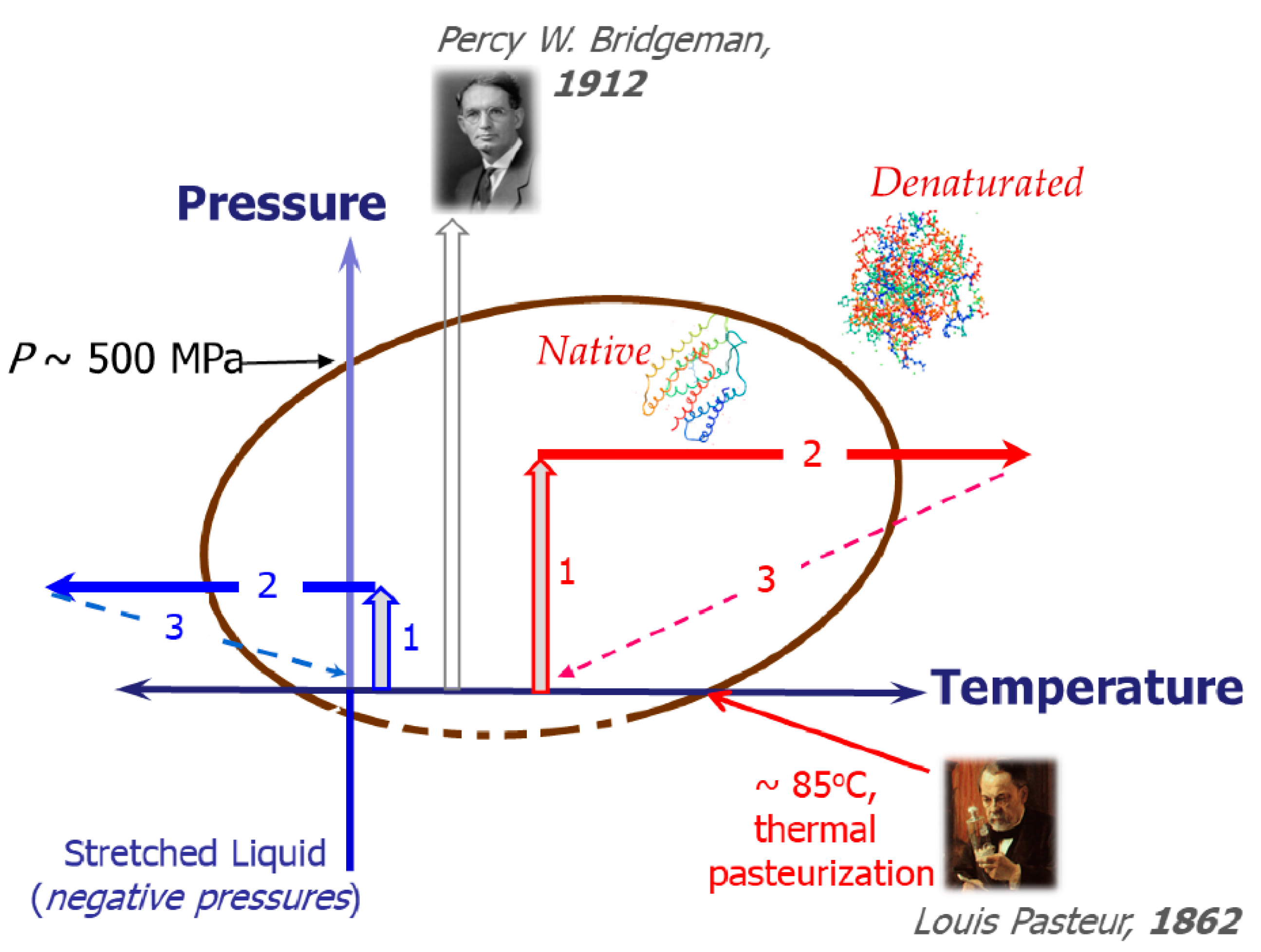

3.2. High Pressure Preservation / Processing of Food

- ✓

- Thermal pasteurization ensures microbiological safety, but at the same time, it often reduces the nutritional, vitamin, and bioactive properties of the products

- ✓

- Chemical additives appeared to be directly related to pandemics of obesity, some types of cancer, allergies, skin problems, and intestinal problem

- ✓

- Cooling and freezing are excellent preservation methods, but using technological solutions supports Global Warming.

- ✓

- irradiation can effectively extend shelf life and improve safety by killing pathogens and insects. However, there are problems related to nutrient degradation and changes in taste and texture.

- shelf-life extension to even up to 180 days!

- high microbiological safety

- fresh product taste, flavor, and texture

- fresh product vitamin composition

- bioactive and nutritional properties maintenance

- no chemical preservatives

- activation/deactivation of selected enzymes

- salt- and sugar limited/free products

- for ‘fluid’ and ‘solid foods

- application to packed food, reducing the risk of secondary contamination

- environment-friendly technology: (i) limited requirements for electric energy- (ii) practical lack of waste during processing, (iii) reduction of ‘expired products’ amount, and then disposal problems

- ‘clean label’, innovative technology

3.3. Compression – Related Sterilization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCorriston, J.; Field, J. A New Introduction to World Prehistory. Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sojecka, A.A.; Drozd-Rzoska, A. Global population: from Super-Malthus behavior to Doomsday criticality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojecka, A.A.; Drozd-Rzoska, A. Verhulst-type equation and the universal pattern for global population growth. PLoS ONE 2025. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Sojecka, A.A.; Drozd-Rzoska, A. Society & Science: Doomsday criticality for the global society. Proc. of 12th Socratic Lectures 2025, 12, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, B.; Skąpska, S.; Niezgoda, J.; Rutkowska, M.; Dekowska, A.; Rzoska, S. J. Inactivation and sublethal injury of Escherichia coli and Listeria innocua by high hydrostatic pressure in model suspensions and beetroot juice. High Pressure Res. 2014, 34, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nema, P.K.; Sehrawat, R.; Ravichandran, C.; Kaur, B.P.; Kumar, A.; Tarafdar, A. Inactivating food microbes by high-pressure processing and combined nonthermal and thermal treatment: a review. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 5797843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojecka, A.A.; Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Rzoska, S.J. Food preservation in the Industrial Revolution epoch: innovative high pressure processing (HPP, HPT) for the 21st-century sustainable society. Foods 2024, 13, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojecka, A.A. ; Drozd-Rzoska Society & Science: High pressures for innovative pro-health foods. Proc. of 12th Socratic Lectures 2025, 12, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M. Malthus and the evolutionists: the common context of biological and social theory. Past & Present 1969, 43, 109–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman, S.A.L.M.; Lika, K.; Starrlight, A.; Nina Marn, N.; Kooi, B.W. The energetic basis of population growth in animal kingdom. Ecological Modelling 2020, 428, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loring, P.A. Coral reefs: moving beyond Malthus. Current Biology 2022, 32, R569–R571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzoska, S. J.; Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Lopez, D.O.; Martinez-Garcia, J.C. Distortions-sensitive analysis of pretransional behavior in n-octyloxycyanobiphenyl (8OCB). J. Phys. Cond. Matter 2013, 25, 245105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Rzoska, S.J.; Zioło, J. Anomalous temperature behavior of nonlinear dielectric effect in supercooled nitrobenzene. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 77, 041501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzoska, S. J.; Paluch, M.; Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Paluch, M.; Janik, P.; Zioło, J.; Czupryński, K. Glassy and fluidlike behavior of the isotropic phase of mesogens in broad-band dielectric. Europ. Phys. J. E 2001, 7, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niven, R. K. q-Exponential structure of arbitrary-order reaction kinetics. Chem. Engn. Sci. 2006, 61, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, P.; Fu, Q.; et al. Single-molecule chemical reaction reveals molecular reaction kinetics and dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhiezer, A.I.; Belozorov, D.P.; Rofe-Beketov, F.S.; Davydov, L.N.; Spolnik, Z.A. On the theory of propagation of chain nuclear reaction. Physica A 1999, 273, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M.; Sharon, M. Nuclear Chemistry. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pyeon, C.H.; Chiba, G.; Endo, T.; Watanabe, K. Basics of nuclear reactor physics. In Reactor Laboratory Experiments at Kyoto University Critical Assembly; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. The Chain Reaction: Pioneers of Nuclear Science (Lives in Science). Franklin Watts: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B. , et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Hood, A.; Davis, C. Eating our way through the Anthropocene. Physiology & Behavior 2020, 222, 112929. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.C. The Industrial Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. Industry 5.0. Introductory Guide to the 5th Industrial Revolution. Editoriale Delfino: Milano, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun, A.; SJagtap, S.; Trollman, H.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Abdullah, A.A.; Goksen, G.; Bader, F.; Ozogul, F.; Barba, F.J.; Cropotova, A.; Munekata, J.P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Food processing 4.0: Current and future developments spurred by the fourth industrial revolution. Food Control 2023, 145, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovianko, M.; Terziyan, V.; Branytskyi, V.; Malyk, D. Industry 4.0 vs. Industry 5.0: co-existence, transition, or a hybrid. Procedia Comp. Sci. 2023, 217, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Driving forces of technological change: The relation between population growth and technological innovation. Analysis of the optimal interaction across countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2014, 82, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O. From Malthusian Stagnation to Modern Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. Behind the Curve: Can Manufacturing Provide Inclusive Growth; Peterson Inst. for Int. Economics: Washington DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Berdegué, J.A.; Trivelli, C.; Vos, R. Employment impacts of agrifood system innovations and policies: A review of the evidence. Global Food Security 2025, 44, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, N. Louis Pasteur. Raintree Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.A. Thermal food preservation techniques (pasteurization, sterilization, canning and blanching). In Conventional and Advanced Food Processing Technologies; Bhattacharya, S., Ed.; Wiley: NY, USA, 2014; chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- Msagati, T.A.M. The Chemistry of Food Additives and Preservatives. Wiley-Blackwell: NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bald, W.B. Food Freezing: Today and Tomorrow; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M.H. Use of ionizing radiation to preserve food. In Nutritional Evaluation of Food Processing; Karmas, E., Harris, R.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Josh, J. An overview of irradiation as a food preservation technique. Nov. Res. Microbiol. J. 2020, 4, 779–789. [Google Scholar]

- Rodica, R.I. Marie Sklodowska Curie: Her Contribution to Science. Lightning Source Inc.: La Vergne (TN), USA, 2017.

- Sen, M. Food Chemistry: The Role of Additives, Preservatives and Adulteration; Wiley and Sons: NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muhsin, N.M.B.; et al. , Review on the Impact of Chemical Preservatives on Health, J. Clinical Trials and Regulations 2022, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.P.; Sati, N. Artificial preservatives and their harmful effects: looking toward nature for safer alternatives. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2013, 7, 2496–2501. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, S. Food preservatives linked to obesity and gut disease. Nature 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobets, T.; Smith, B.P.C.; Williams, G.M. Food-borne chemical carcinogens and the evidence for human cancer risk. Foods 2022, 11, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, A.L.; Schlezinger, J.J.; Corkey, B.E. What are we putting in our food that is making us fat? Food Additives, contaminants, and other putative contributors to obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyambok, E.; Robinson, C. The role of food additives and chemicals in food allergy. Ann. Food Proces. & Preserv. 2016, 1, 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, C.A. Reasons to avoid ultra-processed foods. BMJ 2024, 384, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilson, E.A.F.; Delpino, F.M.; Batis, C.; et al. Premature Mortality Attributable to Ultraprocessed Food Consumption in 8 Countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 25, 0749–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. UNEP, NY, USA, 2024. Available at https://go.nature.com/4dD9dHG 3.

- Jeremić, M.; Matkovski, B.; Đokić, D.; Jurjević, Ž. Food loss and food waste along the food supply chain – an international perspective. Prob. Sust. Develop. 2024, 19, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Poland (Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi, Polska): Food Promotion Strategy. P. 5, 2017. https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/stanowiska-2017. Access 05.05.2025.

- United Nations, FAO: Sustainable Food System. Concept and Framework. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://openknowledge.fao.org/.

- European Union: Knowledge Centre for Food Fraud and Quality. https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/food-fraud-quality/topic/food-quality_en. Access 05.05.2025.

- Houška, M.; Silva, F.V.M.; Evelyn; Buckow, R.; Terefe, N.S.; Tonello, C. High pressure processing applications in plant foods. Foods 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsasekar, A.; Mor, R.S.; Kishore, A.; Singh, A.; Sid, S. Impact of high pressure processing on microbiological, nutritional and sensory properties of food: a review. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 52, 996–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, K.G.; Pandiselvam, R.; Sunil, C.K. High-pressure processing: effect on textural properties of food- a review. J. Food Engn. 2023, 351, 111521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.V.M.; Evelyn. Pasteurization of food and beverages by high pressure processing (HPP) at room temperature: inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and other microbial pathogens. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Chin, N.L.; Sulaiman, A.; Tay, C.H.; Wong, T.H. Microbiological, physicochemical and nutritional properties of fresh cow milk treated with industrial high-pressure processing (HPP) during storage. Foods 2023, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, R.K.; Singla, M.; Kaura, R.; Singh, C.B.; Singh, A. Exploring impact of high pressure processing on the characteristics of processed fruit and vegetable products: a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhu, S.; Ramaswany, H.S.; Yu, Y. High pressure sub-zero concept for improving microbial safety and maintaining food quality: background fundamentals, equipment issues and applications. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyata, E.O.; Bikila, A.M. Effect of high-pressure processing on nutritional composition, microbial safety, shelf life and sensory properties of perishable food products: a review. J. Agric. Food. Nat. Res. 2024, 2, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Waghmare, R. High pressure processing of fruit beverages: A recent trend. Food and Humanity 2024, 2, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazda, P.; Glibowski, P. Advanced technologies in food processing—development perspective. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liao, X. High pressure processing plus technologies: Enhancing the inactivation of vegetative microorganisms. Adv. Food Nutr. Rev. 2024, 110, 145–195. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Z.; Tang, Z. Research progress on bacteria-reducing pretreatment technology of meat. Foods 2024, 13, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauch, H.G. Scientific Method in Brief. Cambridge Univ. Press.: Cambridge, UK, 2012.

- Anstey, P.R. The methodological origins of Newton’s queries. Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. Part A. 2004, 35, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, D. The Life of Sir Isaac Newton. Diamond Publishers: Croydon, UK, 2017.

- Malthus, T. An Essay on the Principle of Population (first published in 1798). In Rethinking the Western Tradition; Stimson, S.C., Ed.; de Gruyter: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, A. The Malthusian Trap. In: The Savage Wars of Peace. Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2003.

- Markert, J. The Malthusian fallacy: prophecies of doom and the crisis of social security. Soc. Sci. J. 2005, 42, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenze, D. The Invention of Scarcity: Malthus and the Margins of History. Yale Univ. Press: New Heaven, CT, USA, 2023.

- Verhulst, P.F. Deuxieme memoire sur la loi d’accroissement de la population. Memoires de l’Academie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 2022, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R. The growth of populations. Quarter. Revi. Biol. 1927, 2, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl R, Reed L. On the rate of growth of the population of the United States since 1790 and its mathematical representation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1920, 6, 275–288. [CrossRef]

- Kapitza, S.P. On the theory of global population growth. Physics Uspekhi 2010, 53, 1287–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaër, N. A Short History of Mathematical Population Dynamics. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011.

- von Foerster, H.; Mora, P.M.; Amiot, L.W. Doomsday: Friday 13 November, A.D. 2026. Science 1960, 132, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taagepera, R. People, skills, and resources: an interaction model for world population growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Changes 1979, 13, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volterra, V. Variations and fluctuations of the number of individuals in animal species living together. J. Cons. Int. pour l’exploration de la Mer 1928, 3, 3–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.E. Population growth and Earth’s human carrying capacity. Science 1995, 269, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, B. E.; Fox, G. A.; Fujiwara, M.; Nogeire, T.M. Demographic heterogeneity, cohort selection, and population growth. Ecology 2011, 92, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M. & Berryman, A. A. Positive and negative feedbacks in human population dynamics: Future equilibrium or collapse? Oikos 2011, 120, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Lueddeke, G. R. Global Population Health and Well- Being in The 21st Century: Toward New Paradigms, Policy, and Practice. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

- Dias, A.; D’Hombres, M.; Ghisetti, B.; Pontarollo, C.; Dijkstra, N. The determinants of population growth: literature review an empirical analysis. Working Papers-10. Joint Research Centre, European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Herrington, G. Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data. J. Indust. Ecol. 2020, 25, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystroff, C. Footprints to Singularity: A global population model explains late 20th century slow-down, and predicts peak within ten years. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O. Population, Technology, and growth: from Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. Am. Econom. Rev. 2000, 90, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, J. The Malthusian fallacy: prophecies of doom and the crisis of social security. Soc. Sci. J. 2005, 42, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, D.N.; Wilde, J. How relevant is Malthus for economic development today? Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaack, L.H.; Katul, G.G. Fifty years to prove Malthus right. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4161–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P. Malthus is still wrong: we can feed a world of 9-10 billion, but only by reducing food demand. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Yi. Malthus’ population theory is still wrong. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2017, 62, 233–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G. Limits: Why Malthus Was Wrong and Why Environmentalists Should Care. Stanford Univ. Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019.

- Montano, B.; Garcia-López, M. S. Malthusianism of the 21st century. Environ. Sustain. Indicator 2020, 6, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenze, D. The Invention of Scarcity: Malthus and the Margins of History; Yale Univ. Press: New Heaven, CT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.; Gaffney, V.; Fitch, S.; Muru, M.; Fraser, A.; Bates, M.; Bates, R. A great wave: the Storegga tsunami and the end of Doggerland? Antiquity 2020, 94, 1409–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A.; Wilson, A. Quantifying the Roman Economy: Methods and Problems. Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 2009.

- Garnsey, P. The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture. Univ. California Press: Los Angeles, USA, 2014.

- Pliny (the Elder), Naturalis Historia. Legare Street Press, Hungerford , UK, 2022:; first edition 77–70 AD, Rome.

- Malanima, P. When did England overtake Italy? Medieval and early modern divergence in prices and wages. Europ. Rev. Econ. 2013, 17, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zwart, P. The long-run evolution of global real wages. J. Econom. Surv. 2025, 99, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G. The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1209–2004. J. Polit. Econ. 2005, 113, 1307–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, C.; Loberg, S.; Wilson, M.; Girham, E. Ecology of the Anthropocene signals hope for consciously managing the planetary ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (PNAS) 2021, 118, e2024150118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, A. Brave New World. Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2004.

- Andrews, P.; Martin, L. Hominoid dietary evolution. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London B 1991, 334, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, K.; Sherrjon, F.; van Vee, E.; Roebroeks, W. Middle Pleistocene fire use: The first signal of widespread cultural diffusion in human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2101108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, O.; Saul, H.; Lucquin, A.; et al. Earliest evidence for the use of pottery. Nature 2013, 496, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhila, P.P.; Sunooj, K.V.; Aaliya, B.; Navaf, M.M. Historical developments in food science and technology. J. Nutr. Res. 2022, 10, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, K.W.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Woelber, J.P. Nutrition and health in human evolution–past to present. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, P.W. The coagulation of albumen by pressure. J. Biol. Chem. 1912, 19, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, P.W. General Survey of Certain Results in the Field of High-Pressure Physics. Nobel Prize in Physics Lecture. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/bridgman-lecture.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Clapeyron, M.C. Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur. J. l'École Polytechnique 1834, 23, 153–190. [Google Scholar]

- Clausius, R. Ueber die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten lassen [On the motive power of heat and the laws which can be deduced therefrom regarding the theory of heat]. Annalen der Physik 1850, 155, 500–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedetti, P.G. Metastable Liquids: Concepts and Principles. Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997.

- Imre, A.R.; Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Horvath, A.; Kraska, T.; Rzoska, S.J. Solid-fluid phase transitions under extreme pressures including negative ones. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2008, 354, 4157–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeller, L.; Heremans, K. Some thermodynamic and kinetic consequences of the phase diagram of protein denaturation. In High Pressure Research in Bioscience and Biotechnology; Heremans, K., Ed.; Leuven Univ. Press: Leuven, Belgium, 1997; pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Heremans, K.; Smeller, L. Proteins in structure and dynamics at high pressure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Protein Struct. Molec. Enzymol. 1998, 1386, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaris, A.; Pexara, A. Inactivation of foodborne viruses by high-pressure processing (HPP). Foods 2021, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyperbaric Company: HPP Blog. High Pressure Thermal Processing (HPTP). 2014. Available online: https://www.hiperbaric.com/en/high-pressure-thermal-processing-hptp/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Li, B.; Kawakita, Y.; Ohira-Kawamura, S.; Sugahara, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Kawaguchi, S.I.; Kawaguchi, S.; Ohara, K.; et al. Colossal barocaloric effects in plastic crystals. Nature 2019, 567, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloveras, P.; Aznar, A.; Barrio, M.; Negrier, P.; Popescu, C.; Planes, A.; Manosa, L.; Stern-Taulats, E.; Avramenko, A.; Mathur, N.D.; et al. Colossal barocaloric effects near room temperature in plastic crystals of neopentylglycol. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li., K.; Li, S.; et al. Thermal batteries based on inverse barocaloric effect. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd0374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Growth Insight. High pressure Processing (HPP) food market size by 2032. Available at: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/high-pressure-processing-hpp-food-market-100548. Access 06.05.2025.

- Adams, F. On Ancient Medicine, Hippocrates of Kos; Dalcassian Publishing Company: Glasgow, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).