1. Introduction

As intracellular protein homeostasis becomes compromised with aging, the accumulation of damaged proteins that are no longer used becomes evident (Demontis et al., 2010; Oka et al., 2015). This age-dependent accumulation has been observed in various organisms, including yeast, nematodes, mice, and humans (Ayyadevara et al., 2016). The substantial presence of mitochondria in muscle cells renders them particularly sensitive to oxidative stress. Consequently, muscle cells frequently exhibit significant accumulation of damaged proteins, which are ubiquitinated. Accumulating these proteins with aging is a reliable indicator of muscle aging progression, as evidenced by previous studies (Bai et al., 2013; Demontis and Perrimon, 2010; Oka et al., 2015). As no such indicators are available in mammalian muscles, the progression of muscle aging can only be estimated by measuring the loss of muscle mass (Larsson et al., 2019). Observing the progression of muscle aging from earlier adult stages using such a simple method is one of the advantages of the Drosophila assay system.

The involvement of oxidative stress accumulation as one factor responsible for the damage of biomaterials and, ultimately, leading to an organism's aging has been argued for some decades (Harman, 1956; Sohal et al., 1993; Ishii et al., 1998). It is well-accepted that damage to intracellular DNA and proteins by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species leads to cellular senescence (Liguori et al., 2018; Beckman and Ames, 1998). When oxidative stress accumulates in cells, the expression of antioxidant genes is induced to protect cells from oxidative damage via a regulatory system called the Keap1-Nrf2 system (Itoh et al., 1999; Yamamoto et al., 2018). Under non-oxidative stress, the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is ubiquitinated by an E3 ligase, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1). Ubiquitinated Nrf2 is subsequently subjected to rapid degradation (Taguchi and Yamamoto, 2017). Conversely, when cells are exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS), the cysteine residues of Keap1 undergo oxidation, thus releasing the inhibitor from Nrf2 (Zhou et al., 2019). This facilitates the nuclear entry of Nrf2 and its binding to antioxidant response element (ARE) sequences present in the genomic DNA. This binding, in turn, promotes the transcription of a set of antioxidant genes that contain these sequences. Subsequently, it enhances antioxidant gene expression (Yu and Xiao, 2021; Taguchi and Yamamoto, 2021).

In addition to the Keap1-Nrf2 system, autophagy is also indispensable in maintaining protein homeostasis via rapidly degrading damaged proteins (Aparicio et al., 2019). Besides proteins that fail to build proper folding structures or are damaged are ubiquitinated by E3 ligase (Kraft et al., 2010), an adaptor protein designated refractory to sigma P (Ref(2)P) in Drosophila/p62 in mammals plays as a key player in this process by binding to the ubiquitinated proteins. The subsequent interaction of damaged proteins and Ref(2)P with autophagy-related 8 (Atg8) on the phagophore results in their incorporation into the formation of the autophagosomes (Zaffagnini and Martens, 2016; Johansen and Lamark, 2011). Subsequently, the fusion of lysosomes with these autophagosomes leads to the degradation of substrate proteins sequestered within the membranous structures (Tanida et al., 2011). Consequently, Ref(2)P, which is simultaneously degraded along with ubiquitinated targets, is a marker that can be utilized to monitor the autophagy level. Moreover, the proteasome degradation system plays a pivotal role in maintaining the homeostasis of proteins and organelles within a cell. This process involves the ATP-dependent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins in muscle by the 26S proteasome (Nandi et al., 2006).

Sesamin (C20H18O6; CAS number 607-80-7) is a major lignan abundant in sesame seeds. Many in vitro studies have demonstrated its biological effects, including antioxidant and anti-carcinogenic effects, on cultured cells (Hou et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2019; Sohel et al., 2022). In addition, several studies have indicated that sesamin has antioxidant or anti-aging effects when administered to living organisms. For instance, it has been documented that administering sesamin to Drosophila adults significantly extends their lifespan (Zuo et al., 2013; Le et al., 2019). A similar observation was made in Caenorhabditis elegans, in which sesamin consumption also led to lifespan extension (Yaguchi et al., 2014). In addition to the lifespan-extending effect, sesamin consumption has been shown to suppress age-related decline in locomotion of Drosophila adults (Le et al., 2019). A subsequent study has reported a similar anti-aging effect in model mice (Kou et al., 2022). When Drosophila adults were fed sesamin, mRNA levels of Sod1 and Sod2, encoding superoxide dismutases that remove ROS, increased (Zuo et al., 2013; Le et al., 2019). Similarly, administering sesamin to cerebral ischemia model mice resulted in reduced necrotic areas in the brain (Cheng et al. 2006). Le and colleagues also reported that sesamin feeding to Drosophila adults mitigates a loss of dopamine neurons in the brains associated with aging (Le et al., 2019). Metabolic intermediates of sesamin have been reported to possess antioxidant properties (Nakai et al., 2003; Kiso, 2004). Moreover, when Drosophila adults and larvae were fed sesamin, the activation of Nrf2 was observed in specific neurons in the brain and digestive tract (Le and Inoue, 2021). Although these findings suggest that the antioxidant effects of sesamin are possibly involved in its anti-aging effect, the overall picture of the fundamental mechanisms underlying these effects remains to be further elucidated. Previous studies did not investigate whether the Keap1-Nrf2 system would be responsible for the antioxidant and anti-aging effects of sesamin in adult muscles.

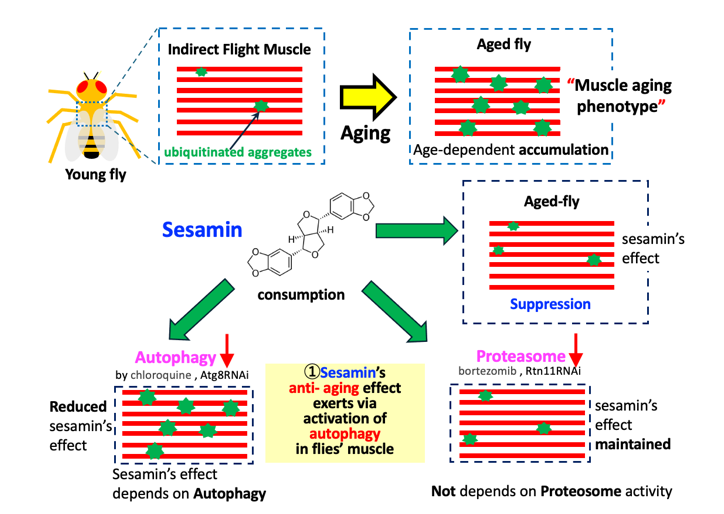

In this study, we conducted experiments to clarify the mechanism through which sesamin suppressed the accumulation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates in Drosophila adults. Furthermore, we investigated whether sesamin consumption promoted autophagy and the proteasome degradation system. The findings from this study will contribute to elucidating the mechanism through which sesamin suppresses the aging phenotype in Drosophila muscles. In addition, this study may provide important information to future research on the interplay between autophagy and the proteasome degradation system during muscle aging. Elucidating the underlying mechanism for the anti-aging effect of sesamin is imperative to further investigate the potential therapeutic applications of sesamin in combating age-related diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drosophila Stocks and Husbandry

For monitoring ARE-dependent transcription, the ARE-GFP reporter (ARE-GFP), in which the cDNA for GFP was placed after ARE sequences on which the Nrf2 transcription factor binds, was used (Chatterjee and Bohmann 2012). A fly stock harboring the ARE-GFP was a gift from D. Bohmann (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA). To induce the ectopic expression of dsRNAs against the relevant mRNAs in muscle, the GAL4/UAS system was used (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). To restrict Gal4 activation in the adult stage, a temperature-sensitive mutant of the Gal80 gene, which encodes an inhibitor of the Gal4 protein, was used. This inhibitor protein for Gal4 is inactivated at the adult stage by transferring the flies at a non-permissive temperature, 28°C (Suster et al., 2004). P{tubP-GAL80ts}; P{GAL4-Mef2.R}R1 (#67063, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) (Bloomington, IN, USA)) (hereafter referred to as Mef2-Gal4) was used for the ectopic expression of muscle cell-specific genes located downstream of the UAS sequences. The following UAS-RNAi stocks were used for RNAi-based gene silencing experiments: P{TRiP.HMS01328}attP40(BDSC -#80428)(UAS-Atg8aRNAi) (Bai et al., 2013) and P{TRiP.HMS00071}attP2 (#33662, BDSC) (UAS-Rpn11RNAi) (Lőw, et al., 2013). These Drosophila stocks were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). P{TRiP.HMS00139}attP2 (UAS-Prosβ1RNAi) was obtained from the National Institute of Genetics (Tsakiri, et al., 2019).

2.2. Chemical Feeding

Young adults from the assay stock were collected within 24 hours of eclosion, as previously described (Le et al., 2019; Le and Inoue, 2021). Ten flies were reared in a single plastic vial containing 0.3 g/ml of Drosophila instant medium (Formula 4-24® Instant Drosophila medium, Blue; Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, NC, USA). Sesamin (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) dissolved in 0.5% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)(67-68-5; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) was added to a final concentration of 2 mg/mL in the instant food. As a control, 0.5% DMSO alone was added to the medium. Chloroquine (CQ)(038-17971; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), an inhibitor of autophagy, was added to the medium at the final concentration described later. Bortezomib (BZ) (038-17971; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), an inhibitor of proteasome, was added to the medium at a final concentration of 10μM. The instant medium contained sufficient nutrients (Le et al., 2019, Tsuji et al., 2024). To feed the flies on the medium at 25 °C, the vials containing the diet were changed to fresh ones every 2 days. To induce ectopic gene expression via the UAS-Gal4 system, the flies were raised at 28 °C. The food vials were changed every 2 days.

2.3. Observation of GFP Fluorescence and Measurement of Intensity in Adult Thoraxes

Young flies carrying the ARE-GFP reporter were collected 2 days after hatching and fed 0.5% DMSO or 2 mg/ml of sesamin at 25 °C. After feeding, individual flies were randomly selected from the DMSO-fed group (control), and one was selected from the sesamin-fed group, and they were placed side-by-side under a fluorescence stereomicroscope (SZX7; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescence images were acquired with a digital camera (DIGITAL SIGHT DS-Fi2, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at a constant exposure time. To quantify the fluorescence intensity, adults were dissected in relaxing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA), and the IFM was removed from the thorax using fine forceps. The muscle fragments were then placed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution to fix them for 30 m. After washing, samples were embedded using Vector Shield to observe GFP fluorescence under a stereo-fluorescence microscope (SZX7; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Immunofluorescence

For muscle immunostaining, indirect flight muscles (IFMs) were collected from the thoraces of flies in a relaxing buffer and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 m. The fixed samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline-triton X-100 (PBST) and blocked with 10% normal goat serum. To detect the ubiquitinated protein aggregates accumulating in muscle, the monoclonal antibody that recognizes both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins (FK2, Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:300. The samples were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After repeated washing with PBST, the samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:400. For the visualization of F-actin, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin (#A12379, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was added simultaneously. After washing with PBST several times, the specimens were embedded with VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV10i, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired at 512 X 512 pixels. FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for image processing.

2.5. Quantifying the Fluorescence Points and Areas in Adult IFMs

For quantifying poly-ubiquitinated protein aggregates, the aggregates, recognized by anti-ubiquitin antibodies, over 10 pixels in a single confocal image (512 x 512 pixels) were counted using ImageJ (ver. 1.53k, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA)(

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, accessed on 31 January 2025). The sizes of fluorescent areas stained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody were measured using ImageJ.

The total fluorescence intensity of foci larger than 10 pixels was selected in each fluorescent image (512 × 512 pixels) using a confocal microscopic field (4.0 × 10−2 mm2). Ten pixels of the fluorescent aggregates were calculated as one unit, as previously described (Ozaki et al., 2022).

2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from the thoraxes of 30 flies using TRIzol reagent (#15596026, Invitrogen). After extracting the homogenates with CIAA (chloroform: isoamyl alcohol = 24:1), nucleic acid in the aqueous phase was precipitated by isopropanol. Traces of DNA were removed via DNase I (Rnase-Free DNase I, #D9905K, Epicentre/Lucigen, Middleton, WI, USA) treatment for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, phenol/CIAA (phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol = 25:24:1) was added to inactivate DNase. The RNA contained in the solution was precipitated by adding isopropanol and collected via centrifugation. Using the purified RNA as a template, cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript II 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (#6210A, Takara Bio., Shiga, Japan) with a random primer. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were independently repeated three times per genotype. qRT-PCR was performed using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (#06402712001, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). qPCR was performed as three independent reactions using LightCycler Nano (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). After denaturing the template DNA at 95 °C for 10 m, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 15 s were repeated. After conducting the final elongation reaction at 72 °C for 30 s, melting curve analysis was performed at temperatures of 60 to 95 °C at 0.1 °C/s. Quantitative analysis was performed using the ΔΔCq method, and RP49 was used as a reference for normalization (Ozaki et al., 2022). The following primers were used: RP49FW: 5’-TTCCTGGTGCACAACGTG-3’; and RP49RV: 5’-TCTCCTTGCGCTTCTTGG-3’

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To compare experimental data between two groups, the F-test was first performed to determine equal or unequal variances. Welch's t-test was performed to test for significance when the value was less than 0.05 (unequal variance). A one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used to compare three or more groups. When there were two independent variables, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used. Differences were considered significant when p-values were less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 9, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

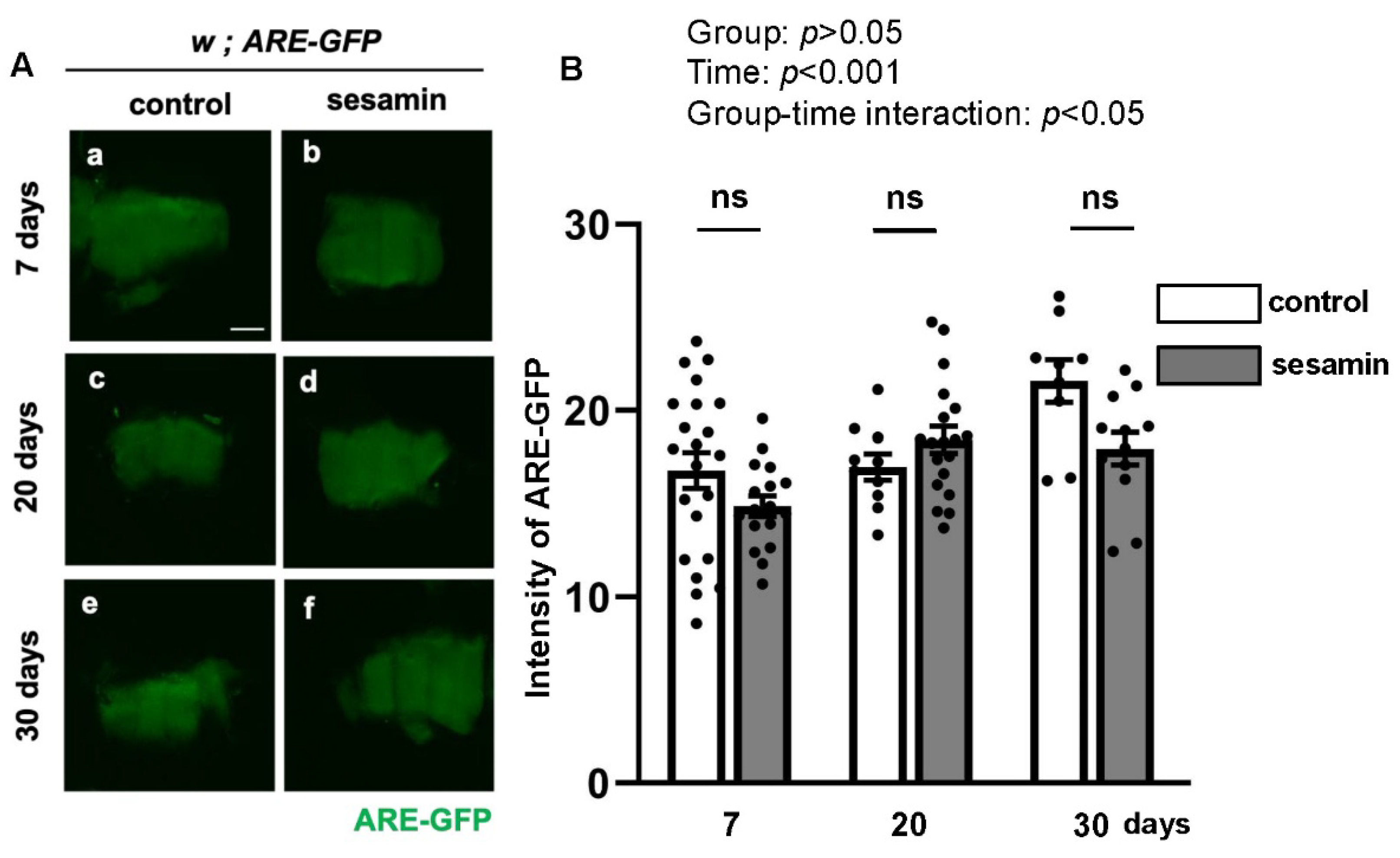

3.1. No Significant Activation of Nrf2 Was Observed in the Muscle of Drosophila Adults Fed Sesamin

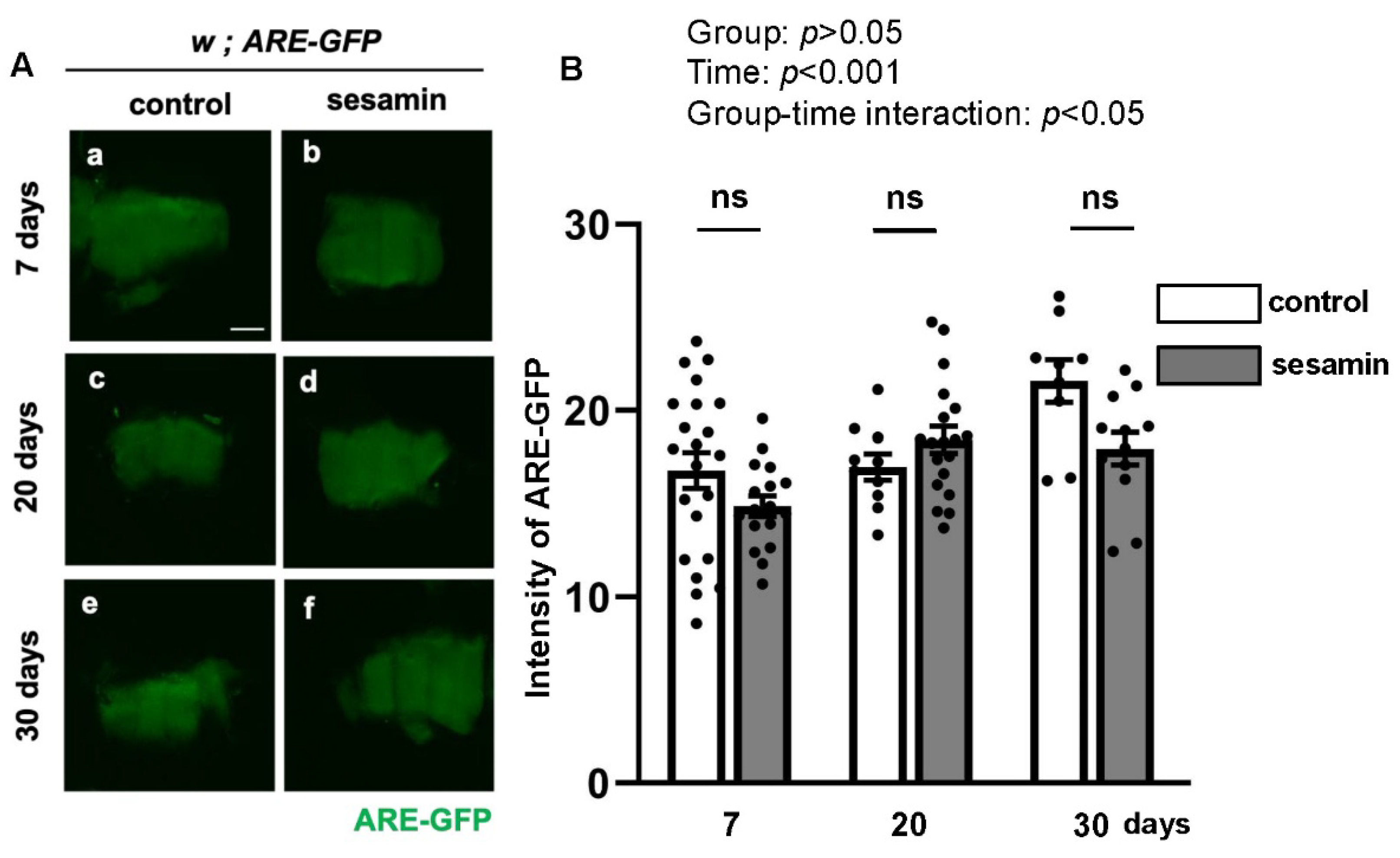

Previous studies have reported that the mRNA levels of several antioxidant and DNA damage repair gene groups increased in the brains of adult flies fed sesamin (Zou et al., 2013; Le and Inoue, 2021). The transcription of these genes is promoted through activating the transcription factor Nrf2. Therefore, we investigated whether sesamin feeding suppresses the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates in muscle cells during aging by activating Nrf2 in muscle. For this purpose,

Drosophila adults expressing an ARE-GFP reporter, in which the GFP gene is located downstream of the Nrf2-binding sequence ARE (Chatterjee and Bohmann, 2012), were fed sesamin for 7, 20, and 30 days immediately after eclosion, and the amounts of fluorescence in thoracic fragments containing indirect flight muscle (IFM) were quantified. When compared with the fluorescence of the flies to which sesamin was not administered, there was no significant difference in GFP fluorescence intensity during any feeding periods compared to the non-sesamin-fed flies at the same age (

Figure 1Aa-f). The difference between the two groups was also not significant (

Figure 1B). Therefore, we conclude that sesamin consumption does not affect the activation of Nrf2 in adult muscle, unlike in adult brains.

In contrast with our finding that there was no significant activation of Nrf2 in the muscle of sesamin-fed Drosophila adults, Nrf2/Cnc is significantly activated in the brains of sesamin-fed Drosophila adults and larvae (Le and Inoue, 2021; Tsuji et al., 2024). One possible reason for this apparent discrepancy is that the regulatory mechanism of Nrf2 in muscle cells may differ from those in other cells. When oxidative stress occurs in cells, the inhibitor Keap1 is released from Nrf2, and its degradation is inhibited. Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and acts as a transcription factor (Kwak et al., 2003, Motohashi et al., 2004). In addition, the phosphorylation of Nrf2 in the cytoplasm by kinases such as PKC, Akt, and ERK is required for this nuclear translocation (Mann et al., 2007). On the other hand, the cytoplasmic volume of the muscle cells is several times larger than that of somatic cells. In such cells, the regulatory mechanism for Nrf2 may differ from those of cultured cells and neurons. In the Drosophila muscle, where damaged mitochondria accumulate due to Parkin or Pink1 depletion, the overexpression of Nrf2 can restore mitochondrial dysfunction (Gumeni et al., 2021). For Nrf2 activation in muscle, it may be necessary to increase the expression level more than in other diploid cells.

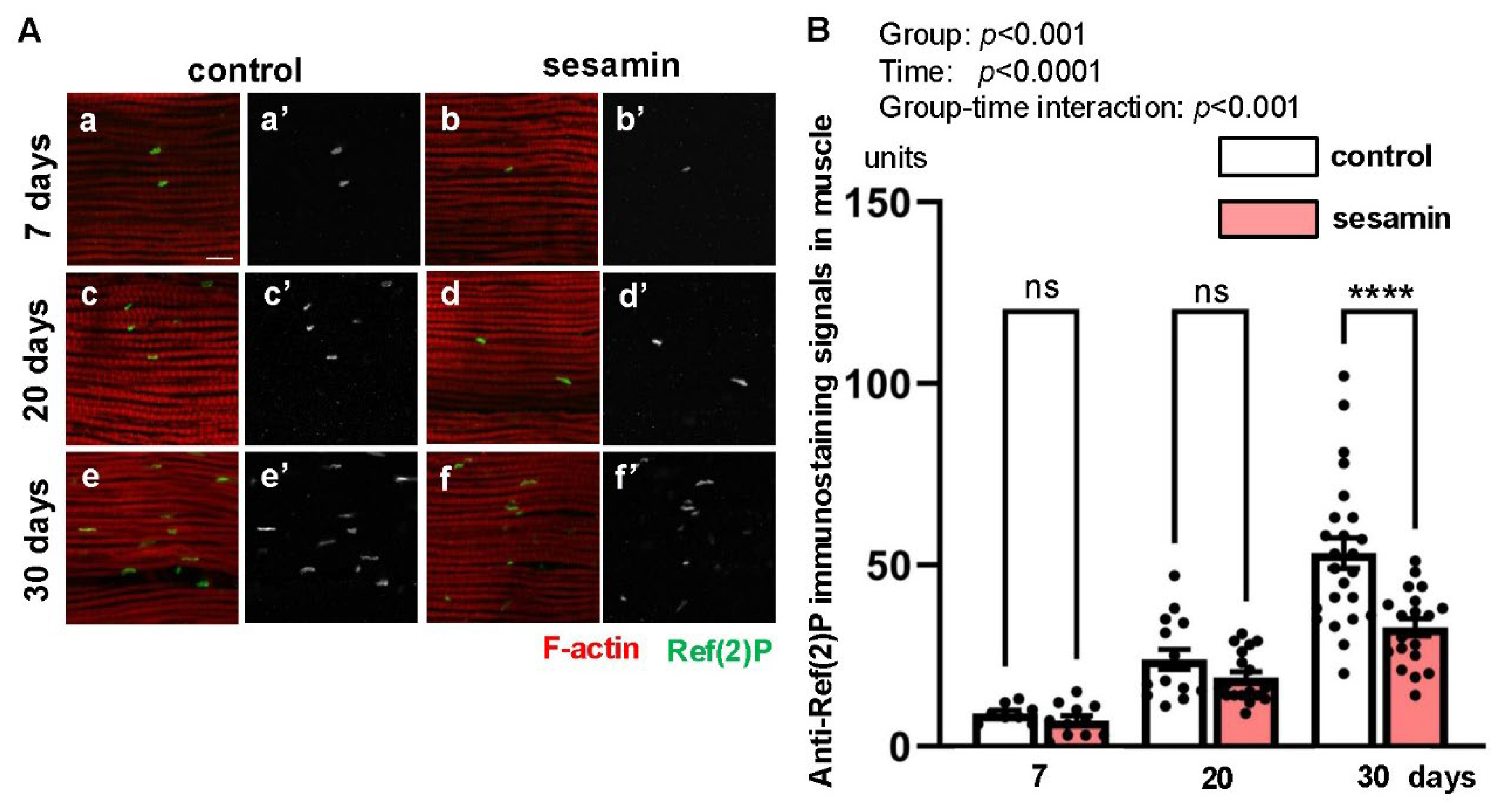

3.2. Sesamin Consumption Enhanced Ref(2)p/p62-Dependent Autophagy in Drosophila Adults’ Muscles

Given that Nrf2 did not appear to drive the anti-aging effect of sesamin, we next focused on autophagy as another candidate for the anti-aging mechanism targeted by sesamin. To assess the activation level of autophagy in adult muscle, we examined the amount of Ref(2)P protein, an autophagy substrate, using immunostaining. The flies were reared for 7, 20, or 30 days after eclosion on a diet supplemented with or without sesamin, and the IFMs from their thoraxes were immunostained with Ref(2)P antibody (

Figure 2A) and the fluorescence intensities of the samples were quantified (

Figure 2B). In the flies fed sesamin for 7 and 20 days, although the average intensities of the Ref(2)P signal were lower in the sesamin-fed flies than those in the control (sesamin-non-feeding) flies at the same ages, the differences between two groups were not significant (

Figure 2B). In contrast, the signal intensity of flies fed sesamin for 30 days was lower than that of the control flies. The difference was statistically significant (

Figure 2B). These results indicate that autophagy is promoted in the muscle of the sesamin-fed group compared to the unfed flies. Therefore, the effect of sesamin consumption on muscle aging may be executed via the promotion of autophagy in muscle.

Even in mammalian cultured cells, when EL4 cells derived from mouse lymphoma are cultured in the presence of sesamin, the amount of p62 protein, a mammalian ortholog of Ref(2)P), decreases compared to when sesamin is not added (Meng et al., 2021). This finding is consistent with the conclusion that sesamin activates autophagy in the muscles of Drosophila adults.

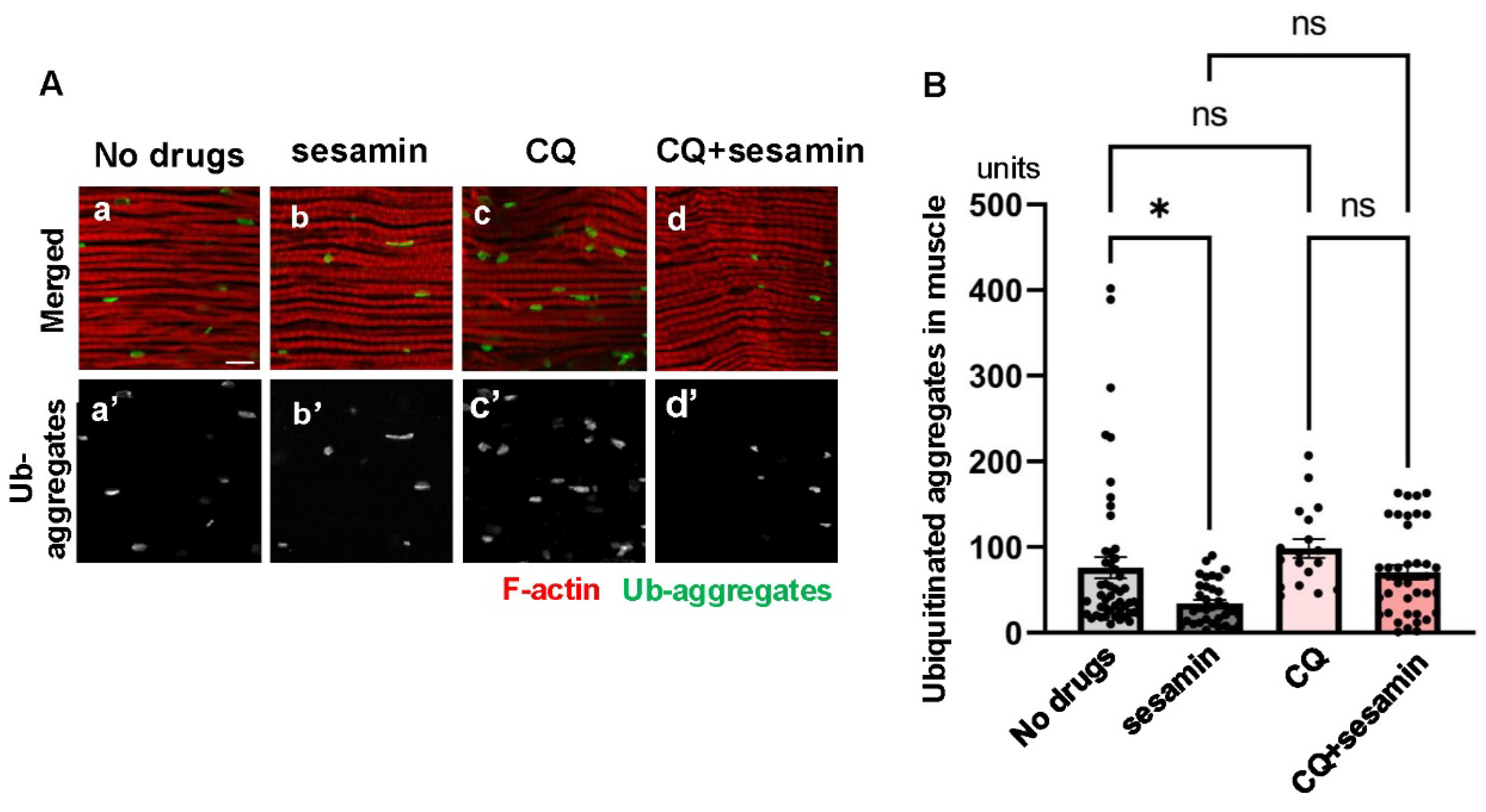

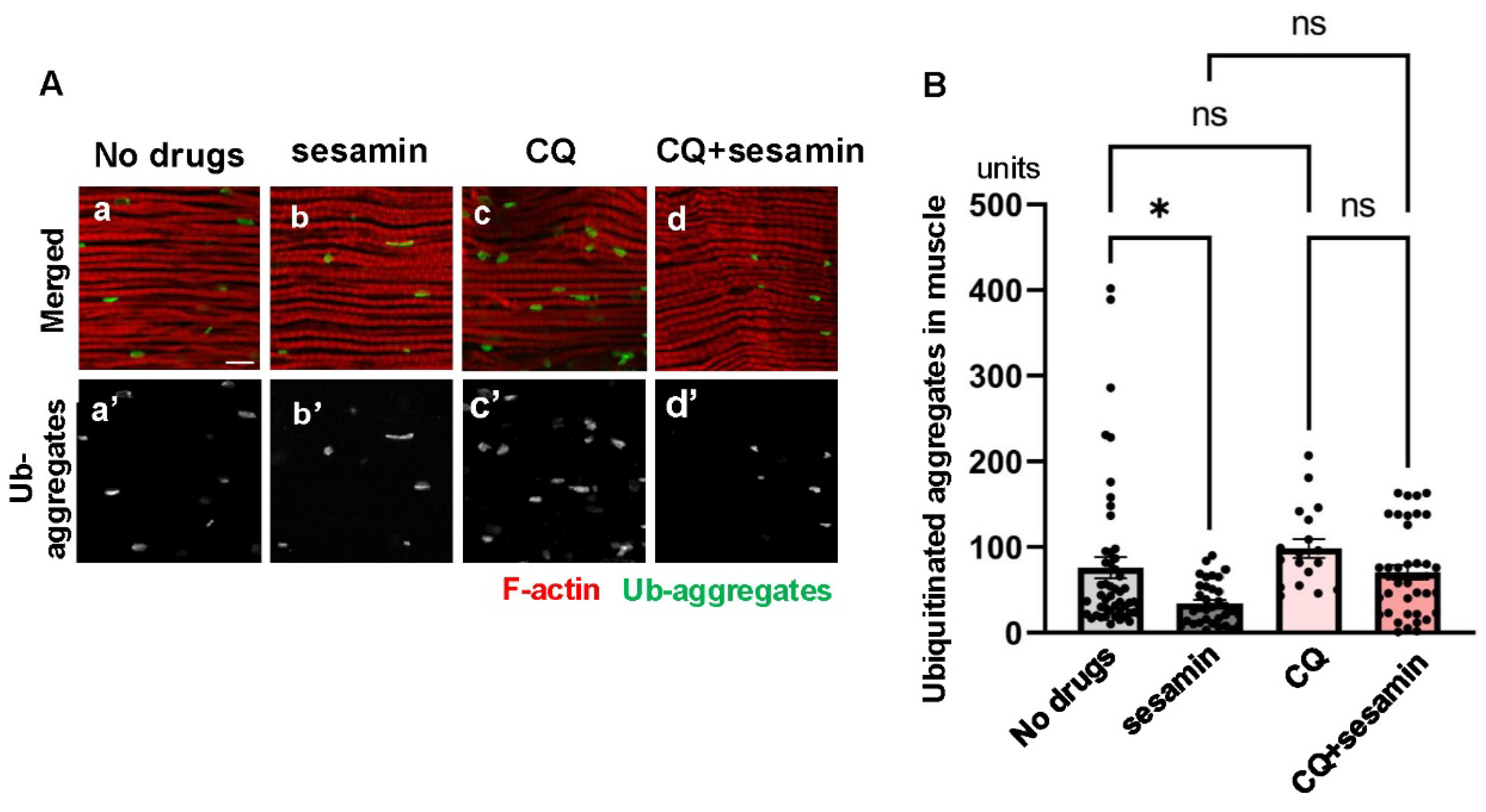

3.3. Sesamin’s Effect Was Diminished in Flies in Which Autophagy Was Inhibited in Muscle, Suggesting That It Targets Autophagy Factors

To confirm that sesamin stimulates autophagy in adult muscle, we tested the suppressive effect of sesamin to be abolished when autophagy was inhibited. We fed an autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine, together with sesamin and quantified the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates in the IFM of the flies. Initially, chloroquine was fed to adults for 20 days at a concentration of 100 µM (Bargiela et al., 2019). However, as ubiquitinated aggregates did not alter by administration at this concentration, we performed this experiment at 1 mM of chloroquine. In muscles from flies fed a diet with chloroquine (Figure S1B), the mean size of the aggregates increased compared to that in muscles from control flies (Figure S1A). Administration at this concentration exerted the effect of the inhibitors. Thus, we next measured the size of aggregates in the IFMs of flies fed 1 mM of chloroquine and 2mg/ml of sesamin simultaneously (the far-right bar in

Figure 3B). The average size of aggregate signals was reduced compared to that in flies fed chloroquine alone (second bar from the right in

Figure 3B), although this difference was not significant (

Figure 3B).

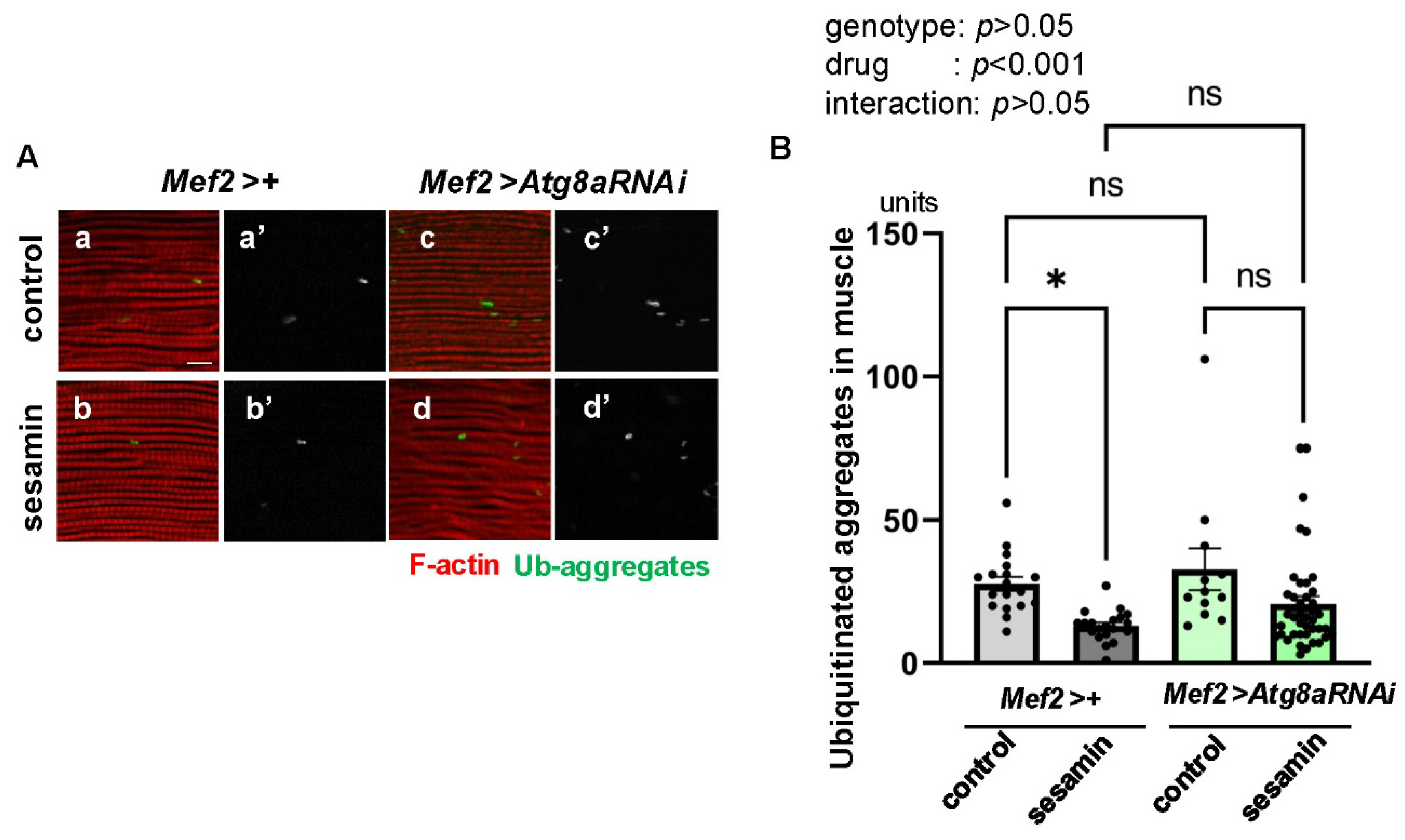

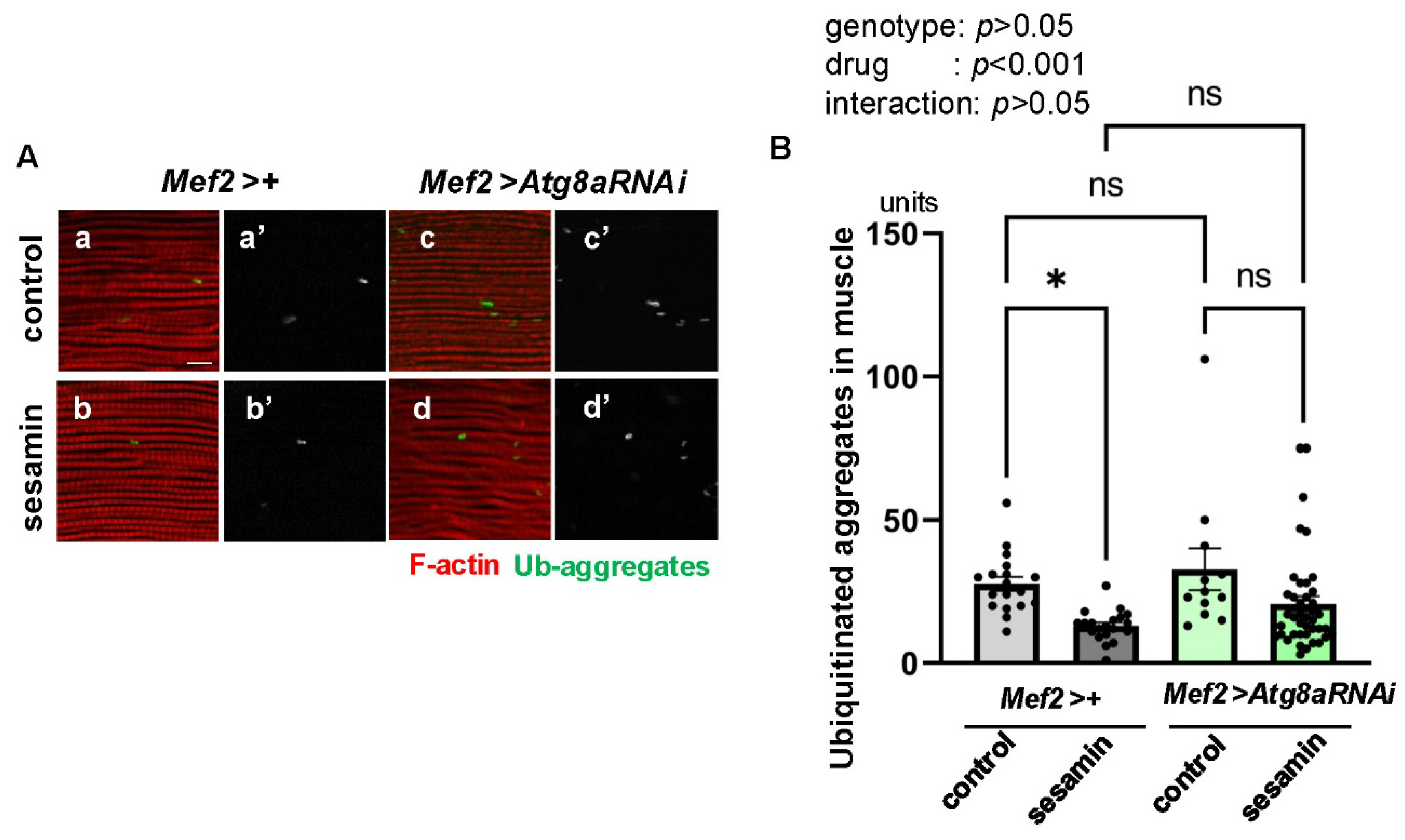

To further confirm the results obtained using the autophagy inhibitor, we next investigated the effect of sesamin by employing an alternative method to inhibit autophagy. Atg8, a protein responsible for forming the autophagosome, was specifically depleted in the muscles of flies (

Mef2 > Atg8RNAi). We then fed sesamin to the flies and observed the ubiquitinated aggregates in their IFMs (

Figure 4A). Initially, the average size of ubiquitinated aggregates in the muscle-specific depletion of

Atg8 (

Figure 4B, third bar from the left) was slightly greater than that in control flies without depletion (

Mef2 > +) (the far-left bar in

Figure 4B). This result suggests that

Atg8 depletion promotes the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates. Thus, we next performed

Atg8 depletion in adult muscle and fed sesamin to flies (the far-right bar in

Figure 4B). No significant difference was observed in the pixel sizes of aggregates compared to the

Atg8-depleted adults not fed sesamin (third from the left) (

Figure 4B). These results suggest that sesamin hinders the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates in muscle and is dependent on autophagy.

The effects of sesamin diminished in the presence of an autophagy inhibitor and through depleting an essential factor for autophagy, suggesting that sesamin may target and stimulate autophagy or related pathways in the flies’ muscles. Estimating a drug’s target based on the results of experiments with specific inhibitors and depleting relevant genes has proven effective in previous studies (e.g., Suzuta et al., 2022). A prior result in mammals is also consistent with our conclusion that sesamin activates autophagy in the muscles of flies after digestion and absorption. When added to normal mammalian liver cells, sesamin stimulates trans-fatty acid-induced autophagy by increasing the levels of transcription factor EB (TFEB) and its downstream target lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1). This can reduce lipid accumulation in cultured cells (Liang et al., 2024). We anticipate a similar anti-aging effect of sesamin being present in living organisms. It is necessary to verify this assumption in mammalian models and to consider whether it can be extrapolated to humans in the future.

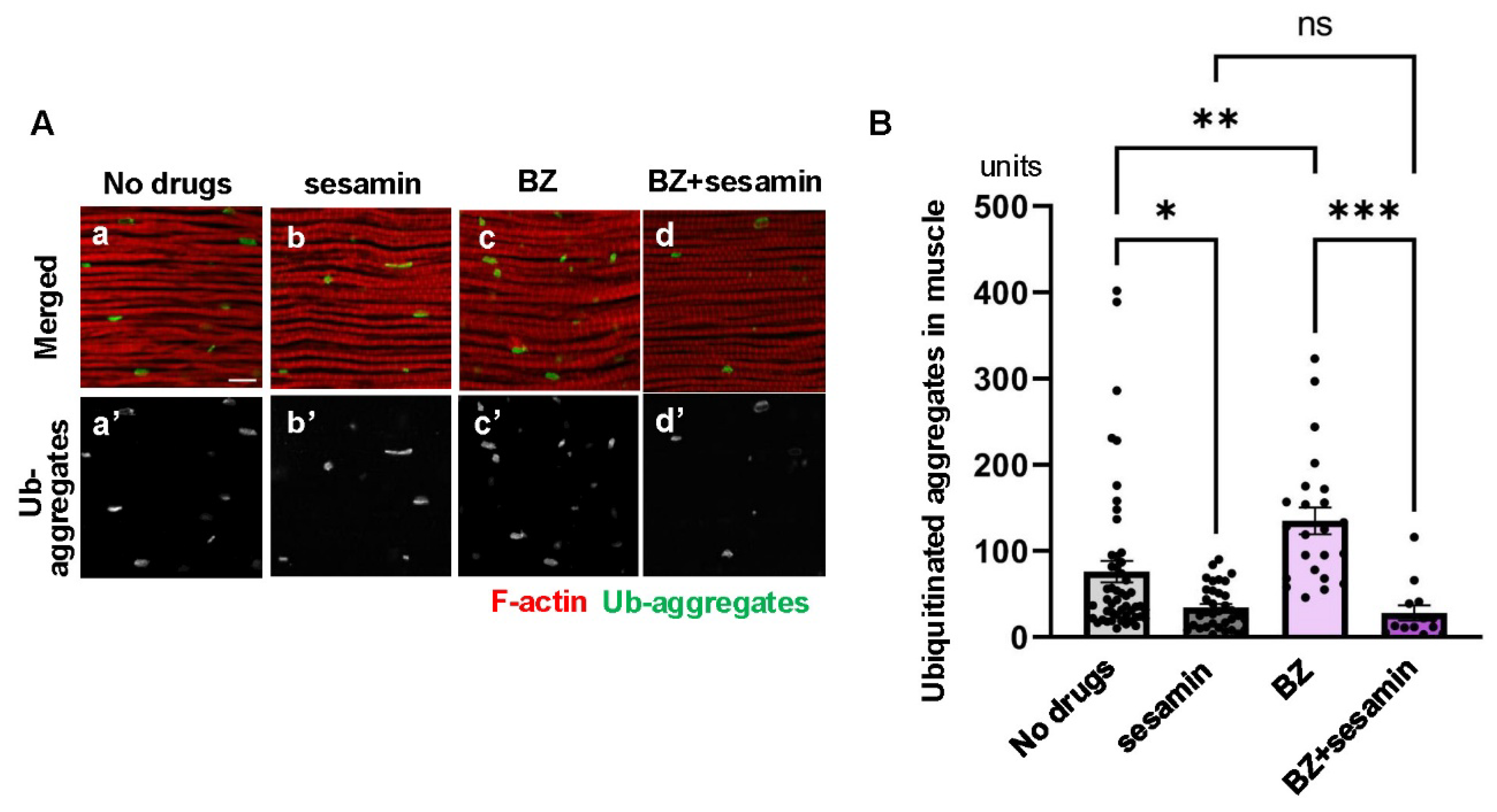

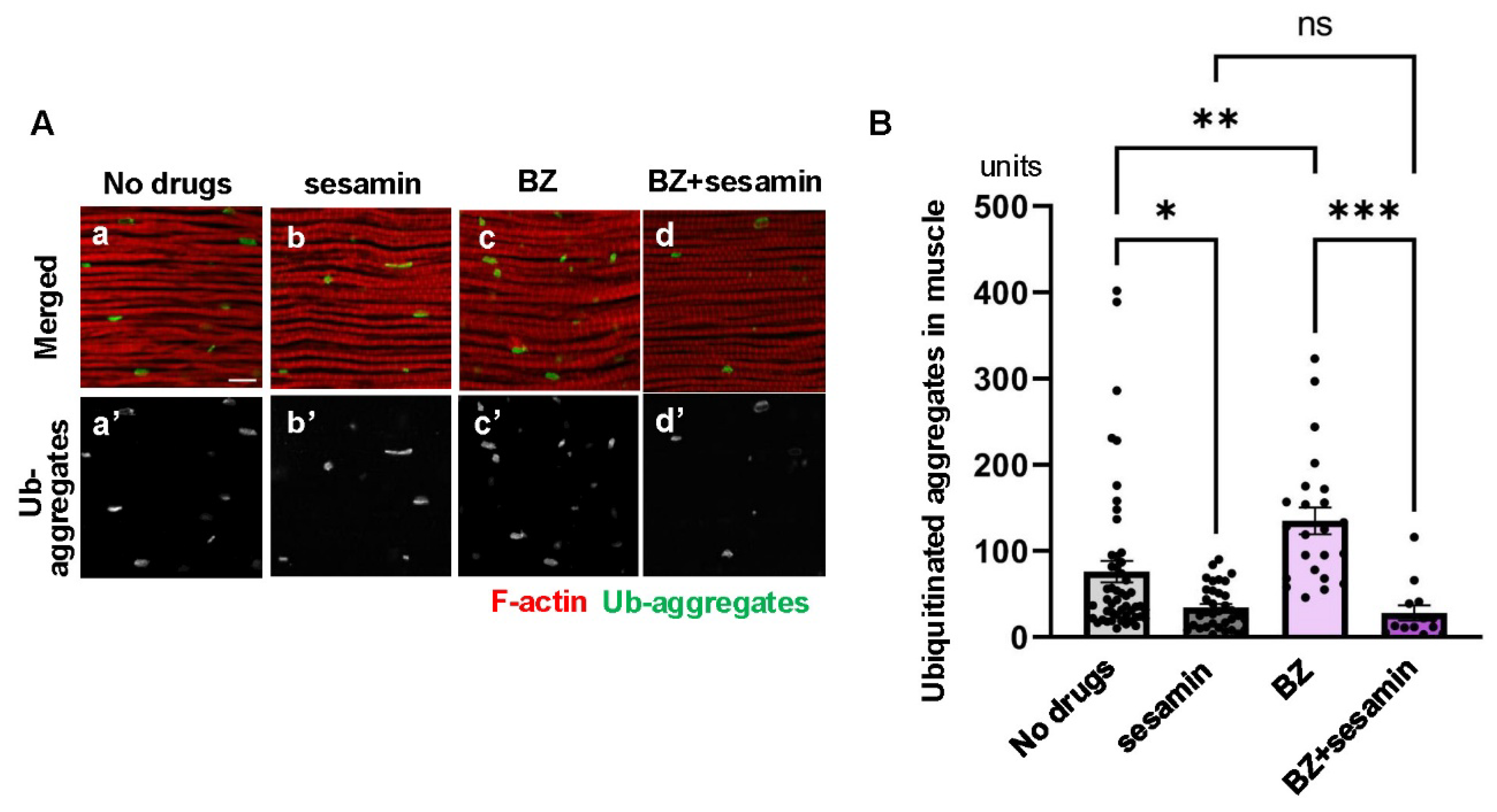

3.4. Sesamin’s Effect Was Maintained in Flies in Which the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Was Downregulated

The ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system is another pathway for eliminating damaged proteins within cells (Kitajima et al., 2014). We examined the effects of sesamin on the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system by simultaneously feeding flies with bortezomib (BZ), a proteasome inhibitor, and sesamin after eclosion. As 10 µM of BZ was effective throughout the adult body (Velentzas et al., 2013), BZ at the concentration administered to the young flies for 20 days with a diet. The mean size of aggregates in adult muscles (

Figure 5A, the third bar from the left in 5B) was greater than that of control adults fed a diet without the inhibitor (the far-left bar in

Figure 5B). Enhancing ubiquitinated aggregate accumulation thus confirms the effect of the inhibitor. Conversely, the muscles of flies fed BZ and sesamin concurrently (the far-right bar in

Figure 5B) showed a reduced accumulation of aggregates more efficiently compared to those fed only BZ (second from the right in

Figure 5B). These results suggest that, despite administering the proteasome inhibitor, the inhibitory effect of sesamin on aggregate accumulation was maintained.

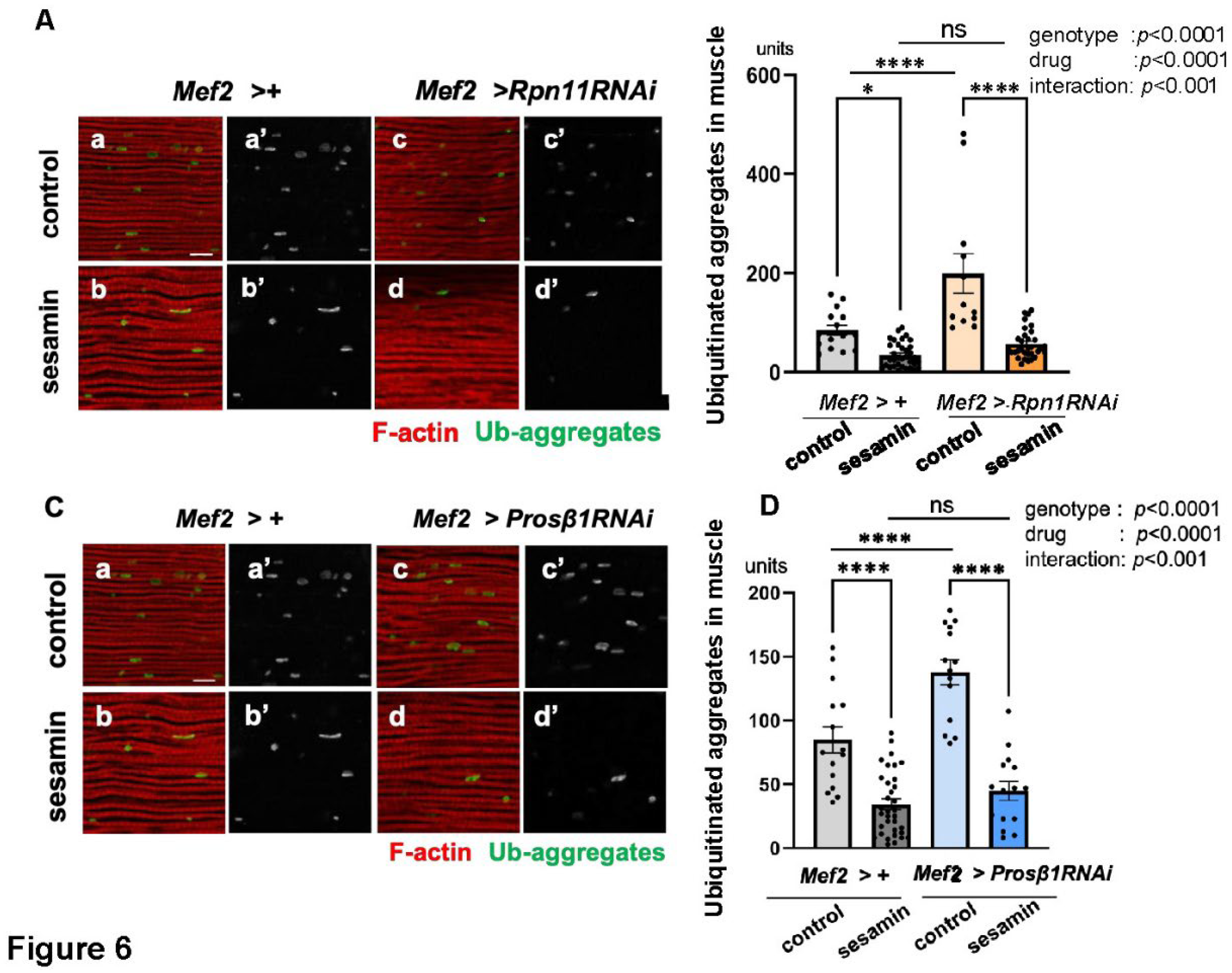

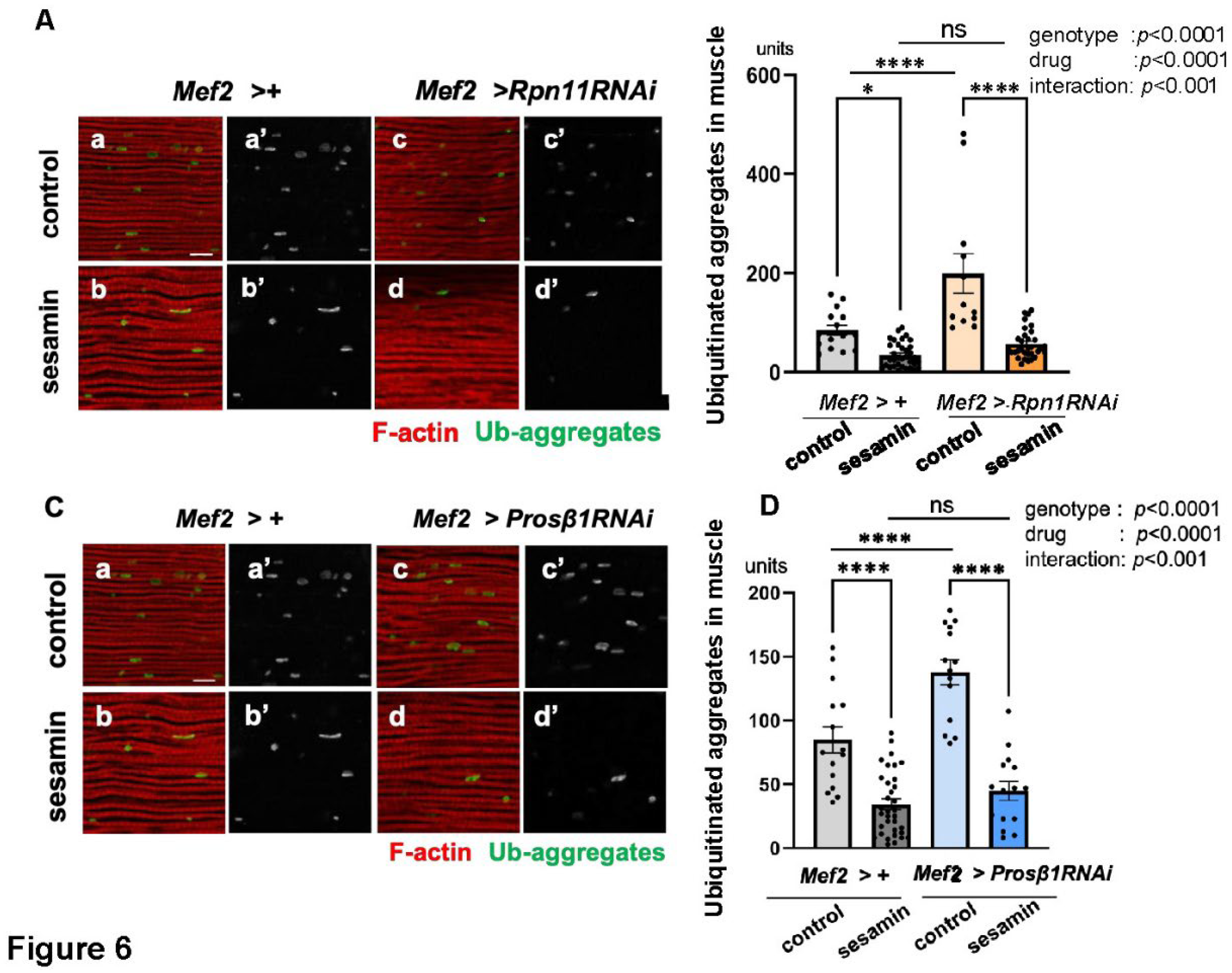

Next, the results obtained with the inhibitor were corroborated using an alternative method. The adult muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11, a component of the proteasome, aimed to downregulate proteasome levels in adult muscle. The depleted flies were fed sesamin for 20 days after eclosion. The accumulated aggregates increased in the muscle where Rpn11 was depleted (

Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi)(third bar from the left in

Figure 6B), compared to the controls (the far-right in

Figure 6B). After confirming the effects of

Rpn11 depletion (the far-left bar and the third bar from the left in

Figure 6B), the inhibitory effect of sesamin on the accumulation of the aggregates was examined (

Figure 6B). The

Rpn11-depleted flies fed sesamin had reduced amounts of aggregates in the muscle compared to those that were not fed sesamin (the far-right bar and next to the right in

Figure 6B). We further confirmed the results using flies with adult muscle-specific depletion of Prosβ1, which encodes a proteasome component (the fair-right bar and bar next to the right in

Figure 6D). These results show that the effect of sesamin was maintained even in the proteasome-depleted muscles, strongly suggesting that sesamin is unlikely to be a target of this degradation pathway.

In mammalian cultured cells, inhibiting proteasome activity with BZ leads to the accumulation of ROS in mitochondria, causing functional impairment of the organelles. Consequently, cell death is induced. Simultaneously adding an antioxidant resveratrol or sesamin inhibits ROS accumulation, preventing mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death (Mahrjan et al., 2014). This finding may be inconsistent with our results. Further investigation is needed to determine whether this discrepancy is due to differences between species or cell types.

Our current data suggest that sesamin does not target the proteasome degradation system in Drosophila muscle. This may relate to sesamin not activating Nrf2. In mammals, the ARE sequences to which Nrf2 binds are located in the promoter regions of genes encoding 20S proteasome subunits, and Nrf2 promotes their transcription. When the transcription factor is knocked down in mouse ES cells, the proteasome cannot be activated even under oxidative stress (Pickering et al., 2012). The proteasome degradation system may not be stimulated unless Nrf2 is activated. In particular, it may be crucial to increase the expression levels of proteasome components in muscle cells, which are noticeably large. Although we speculate that sesamin does not affect the proteasome degradation system in Drosophila muscle, we did not directly measure the proteasome level in muscle due to the lack of simple and effective markers. Even so, the experimental results suggesting that the number and size of ubiquitinated aggregates did not alter when the regulatory or catalytic subunits were depleted, suggesting that sesamin does not target the proteasome degradation system. However, this is a limitation of this study that should be addressed by measuring the proteasome activity in the future.

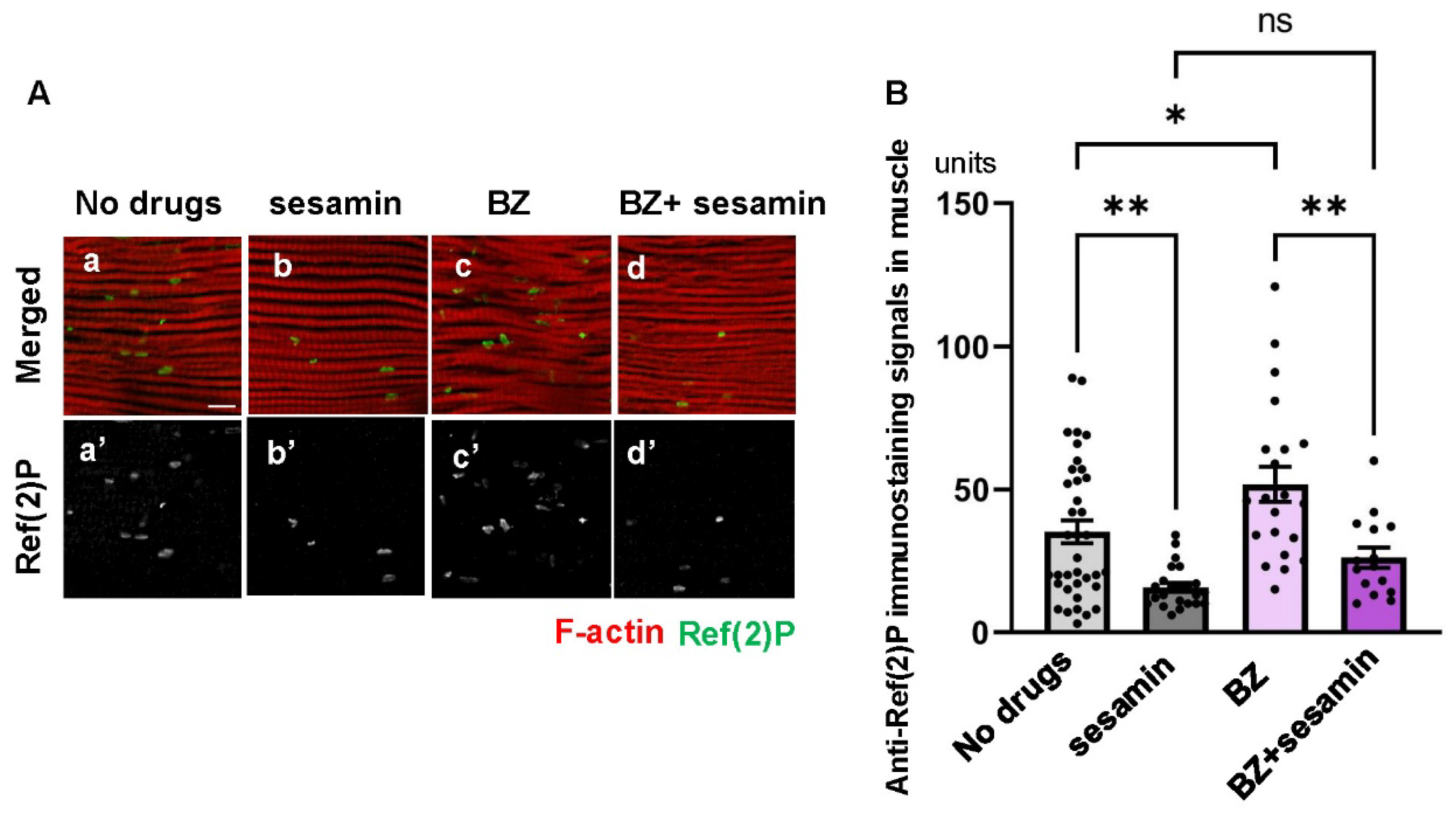

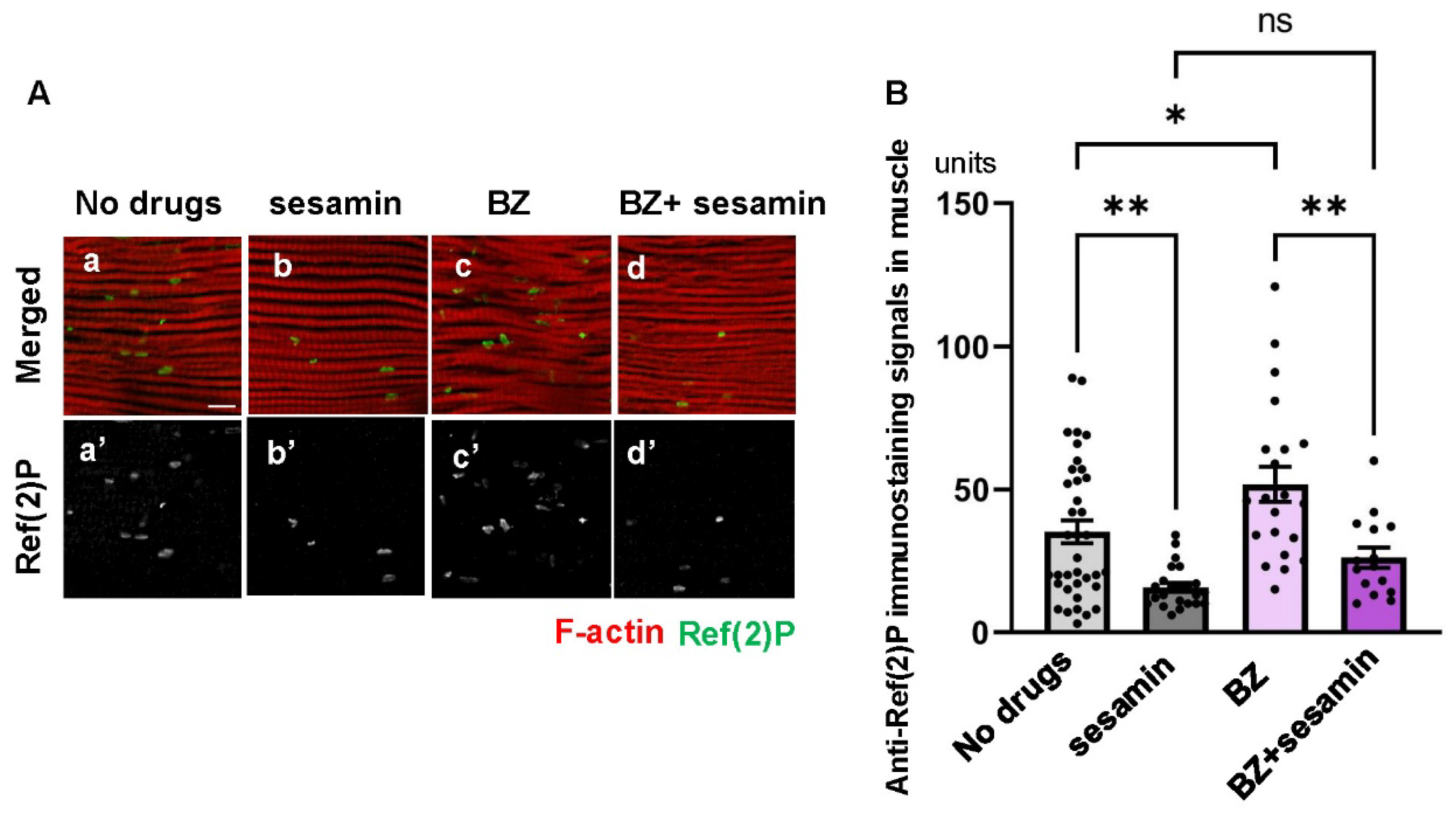

3.5. Sesamin Stimulated Autophagy in the Drosophila Muscles Even When the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Was Downregulated

We then tested whether sesamin suppressed the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates, even when the proteasome degradation system was inhibited. For this purpose, we first compared the anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signal (

Figure 7A), which becomes less pronounced as the level of autophagy rises, between flies fed both sesamin and the proteasome inhibitor BZ for 20 days after eclosion (the far-left bar in

Figure 7B), and compared it with similarly aged flies fed only BZ (second bar from the right in

Figure 7B). This data indicates that sesamin consumption stimulates autophagy in the muscle even when the proteasome degradation system is inhibited by BZ administration.

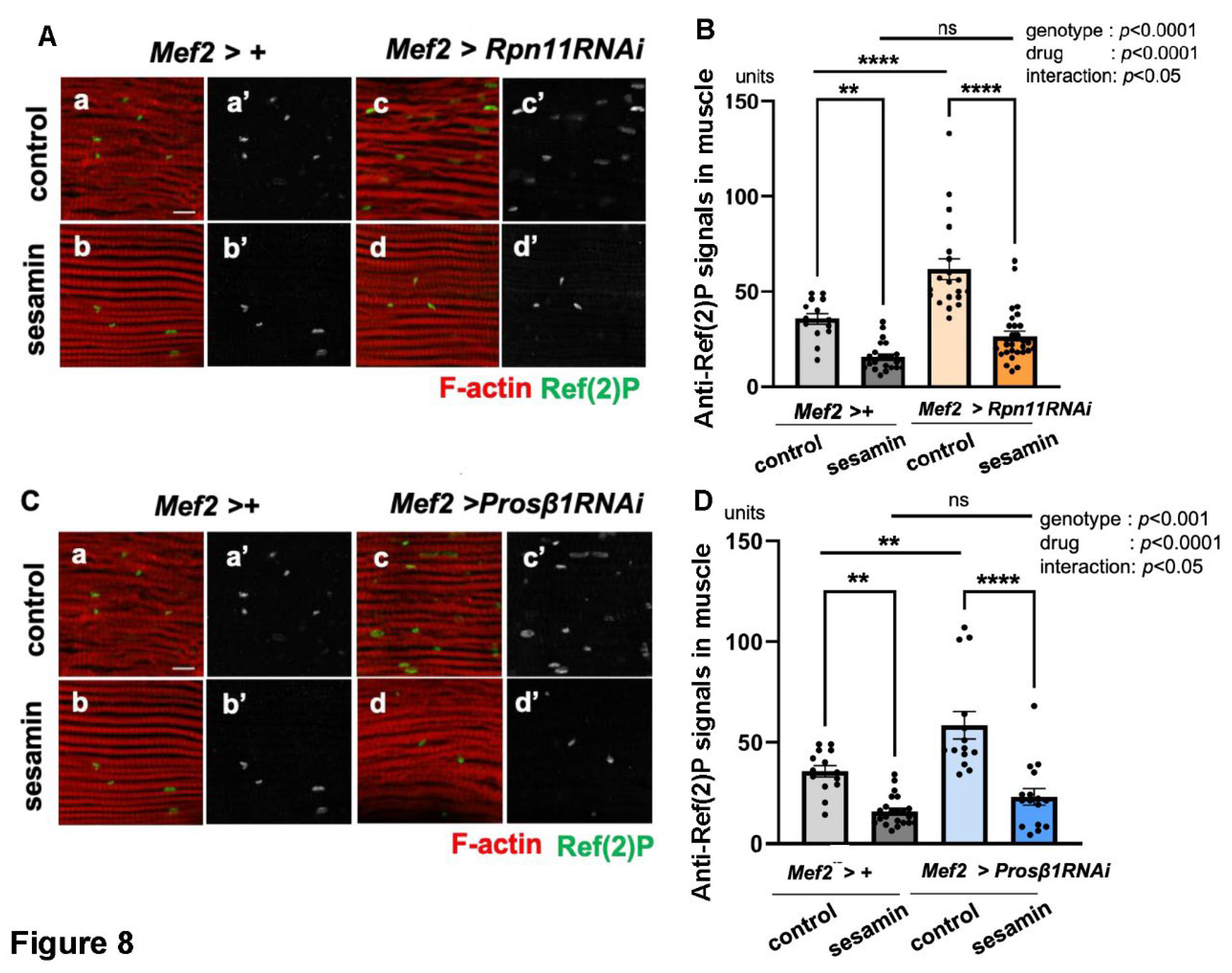

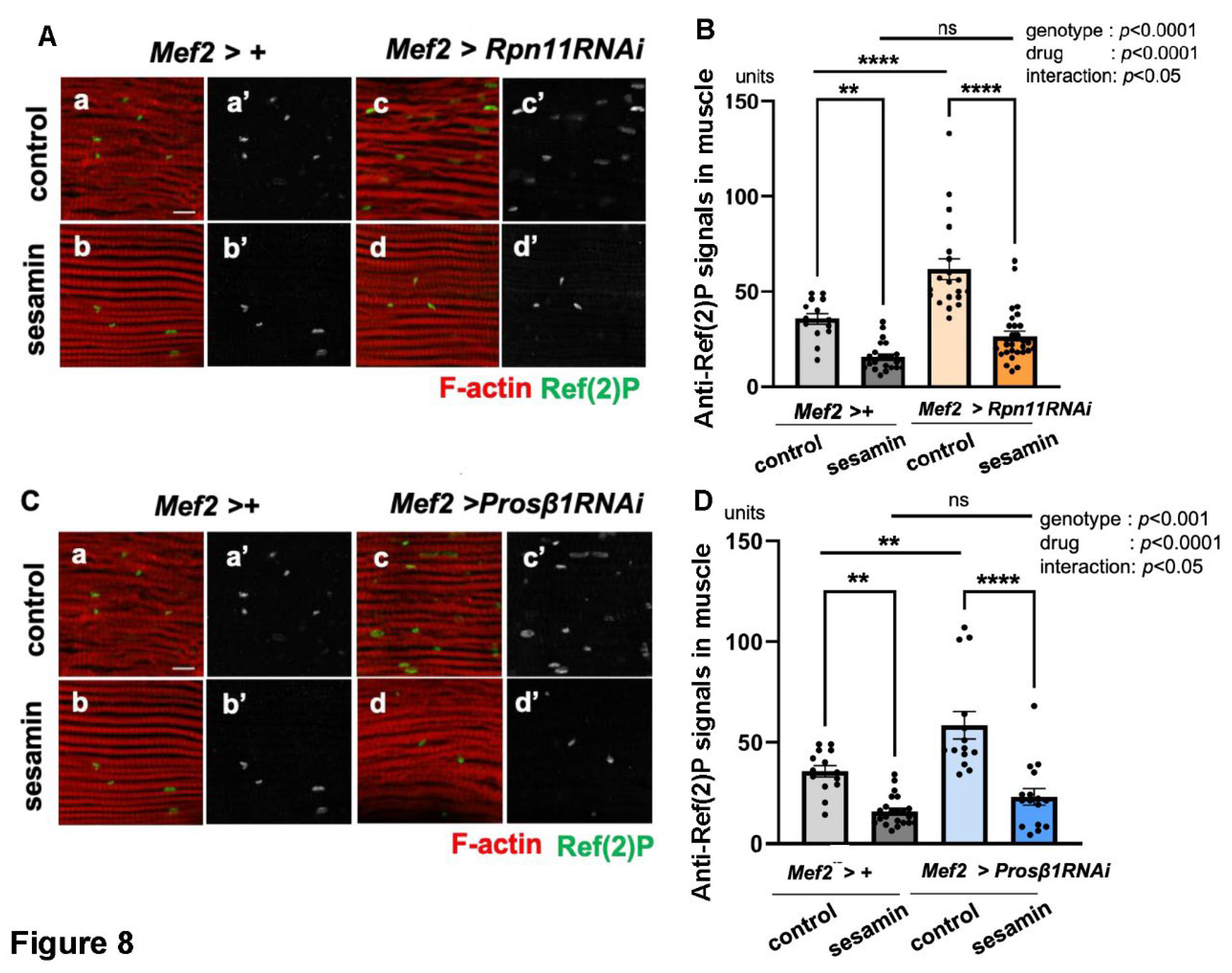

Next, we confirmed the results by downregulating the proteasome through a genetic method targeting the adult muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11, a component of the regulatory subunits of the proteasome (

Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). The intensity of the Ref(2)P signal was less prominent in the

Rpn11-depleted flies fed sesamin (

Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (the far-right bar in

Figure 8B) than that in the adults without sesamin administration (

Mef2 > +) (next to the right in

Figure 8B), suggesting that sesamin consumption still stimulated autophagy in the

Rpn11-depleted muscle. To further corroborate this finding, we observed sesamin-fed adults with muscle-specific depletion of Prosβ1, a component of the proteasome catalytic subunit (

Figure 8C). Consistently, we observed a reduced Ref(2)P signal in the muscles of adults compared to sesamin-non-fed flies with

Prosβ1 depletion (the far-right bar and second bar from the right in

Figure 8D), suggesting that sesamin consumption stimulated autophagy in the

Prosβ1-depleted muscle. Taken together, we concluded that the effect of sesamin in activating autophagy was maintained even when proteasomes were compromised in adult muscle. Sesamin can suppress the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates in the flies’ muscles by stimulating autophagy even under the inhibition of the proteasome degradation system. This conclusion is consistent with the results described in previous sections. To further confirm the current conclusion, future studies using cultured cells and mammalian models remain to be performed.

3.6. Inhibiting the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Also Affects Autophagy in Drosophila Adult Muscle

In addition to the finding that sesamin promotes autophagy in adult muscles, we next investigated whether down-regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system influenced autophagy. Another important finding emerges from a careful interpretation of the results shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. Autophagy in the IFMs of

Drosophila adults fed a proteasome inhibitor, BZ was investigated by anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining. The signals were observed at an average of 51.2 units per confocal microscopic field in the IFMs of flies fed BZ (

Figure 7Ac, third bar from the left in

Figure 7B). This marks a 45.5% increase in the staining signal compared to the muscles of adults not administered the inhibitor (

Figure 7Aa, average of 35.2 units/field, the far-right bar in

Figure 7B). In other words, BZ administration reduces the proteasome as well as autophagy levels in adult muscles. To confirm the results, we performed anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining in flies with muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11, a component of the 19S proteasome subunit (

Mef2 >Rpn11RNAi). We detected an average of 61.7 units of Ref(2)P signals in the muscle (third bar from the left in

Figure 8B). Compared to similarly aged adults without

Rpn11 depletion (35.6 units/field) (the far-left bar in

Figure 8B), there was a 42.3% increase in Ref(2)P signals (

Figure 8B), indicating that the autophagy level was lower than that in the controls without depletion. Furthermore, we quantified the Ref(2)P signal in adult muscle in which the 20S proteasome component was depleted. In control muscles without depletion, an average of 35.6 units/field of the signal was observed (the far-left bar in

Figure 8B). In contrast, in the muscle with

Prosβ1 depletion (

Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi), an average of 58.5 units of Ref(2)P signal/field was detected (third bar from the left in

Figure 8D). Thus, when the proteasome was downregulated through administering its inhibitor or depleting the proteasome components, autophagy in adult muscle was reduced.

Consistent with these findings, another study has reported similar outcomes. When Rpn1, a component of the 19S subunit of the proteasome, is depleted in Drosophila larval muscle, the Atg8 signals decrease. The author claimed that the long-term inhibition of the proteasome reduces larval locomotor activity and inhibits the formation of autophagosomes in the muscle (Zirin, et al., 2015). This study demonstrated that autophagy was concomitantly compromised when the proteasome was inhibited for 20 days after eclosion. These results imply a possible interplay between autophagy and the proteasome in adult muscles during the aging process. This mechanism needs further clarification in the future.

4. Conclusions

Sesamin has been reported to prolong the lifespan of Drosophila adults, reduce the decline of locomotor activity associated with aging, and suppress oxidative damage to specific neurons via activation of Nrf2. By contrast, this study revealed that sesamin delays the muscle aging phenotype by not activating the Nrf2 transcription factor but activating autophagy and promoting the removal of damaged proteins. Sesamin could be used therapeutically as a substance with a defined mechanism of action against muscle aging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.I.; methodology, Y.Y and Y.H.I.; validation, Y.Y. and Y.H.I.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Y.; data curation, Y.H.I.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.I.; visualization, Y.H.I.; supervision, Y.H.I. and N.T.; project administration, Y.H.I.; funding acquisition, Y.H.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 17K07500 to Y.H.I.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because its experimental plan is not restricted under Japanese law.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Bohmann (Rochester Univ. Rochester, NY, USA) for providing the fly stock. We also thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and the National Institute of Genetics for providing fly stocks. We acknowledge A. Watanabe and M. Platt (Kyoto Institute of Technology) for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Demontis, F.; Perrimon, N. FOXO/4E-BP Signaling in Drosophila Muscles Regulates Organism-Wide Proteostasis during Aging. Cell 2010, 143, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, S.; Hirai, J.; Yasukawa, T.; Nakahara, Y.; Inoue, Y. H. A Correlation of Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation by Depletion of Superoxide Dismutases with Age-Dependent Impairment in the Nervous System and Muscles of Drosophila Adults. Biogerontol. 2015, 16, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyadevara, S.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Suri, P.; Mackintosh, S. G.; Tackett, A. J.; Sullivan, D. H.; Shmookler Reis, R. J.; Dennis, R. A. Proteins That Accumulate with Age in Human Skeletal-Muscle Aggregates Contribute to Declines in Muscle Mass and Function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 3486–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Kang, P.; Hernandez, A. M.; Tatar, M. Activin Signaling Targeted by Insulin/DFOXO Regulates Aging and Muscle Proteostasis in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, YI.; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L. ; Sandri, Sarcopenia, M: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol Rev. 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D; Aging; A Theory Based on Free Radical and Radiation Chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300. [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Agarwal, S.; Dubey, A.; Orr, W.C. Protein Oxidative Damage is Associated with Life Expectancy of Houseflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993, 90, 7255–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, N.; Fujii, M.; Hartman, P. S.; Tsuda, M.; Yasuda, K.; Senoo-Matsuda, N.; Yanase, S.; Ayusawa, D.; Suzuki, K. A Mutation in Succinate Dehydrogenase Cytochrome B Causes Oxidative Stress and Ageing in Nematodes. Nature 1998, 394, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; Abete, P. Oxidative Stress, Aging, and Diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, K. B.; Ames, B. N. The Free Radical Theory of Aging Matures. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78, 547–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J. D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 Represses Nuclear Activation of Antioxidant Responsive Elements by Nrf2 through Binding to the Amino-Terminal Neh2 Domain. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1–NRF2 System in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, H.; Xu, Z.; Tong, R.; Shi, J.; Jia, G. Recent Advances of Natural Polyphenols Activators for Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1900400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, J.-H. The Keap1-Nrf2 System: A Mediator between Oxidative Stress and Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, e6635460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1–NRF2 System as a Molecular Target of Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, R.; Rana, A.; Walker, D. W. Upregulation of the Autophagy Adaptor P62/SQSTM1 Prolongs Health and Lifespan in Middle-Aged Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, C.; Peter, M.; Hofmann, K. Selective Autophagy: Ubiquitin-Mediated Recognition and Beyond. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffagnini, G.; Martens, S. Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 1714–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Lamark, T. Selective Autophagy Mediated by Autophagic Adapter Proteins. Autophagy 2011, 7, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, I. Autophagy Basics. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, D.; Tahiliani, P.; Kumar, A.; Chandu, D. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. J. Biosci. 2006, 31, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, R. C.-W.; Huang, H.-M.; Tzen, J. T. C.; Jeng, K.-C. G. Protective Effects of Sesamin and Sesamolin on Hypoxic Neuronal and PC12 Cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 74, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Song, M.; Gao, G.; Zhou, Z. Suppression of cyclooxygenase 2 increases chemosensitivity to sesamin through the Akt-PI3K signaling pathway in lung cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel, M.; Islam, M.N.; Hossain, M.A.; Sultana, T.; Dutta, A.; Rahman, M.S.; Aktar, S.; Islam, K.; Al Mamun, A. Pharmacological Properties to Pharmacological Insight of Sesamin in Breast Cancer Treatment: A Literature-Based Review Study. Int. J. Breast Cancer. 2022, 2022, 2599689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Peng, C.; Liang, Y.; Ma, K. Y.; Chan, H. Y. E.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.-Y. Sesamin Extends the Mean Lifespan of Fruit Flies. Biogerontol. 2013, 14, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Nakahara, Y.; Ueda, M.; Okumura, K.; Hirai, J.; Sato, Y.; Takemoto, D.; Tomimori, N.; Ono, Y.; Nakai, M.; Shibata, H.; Inoue, Y.H. Sesamin Suppresses Aging Phenotypes in Adult Muscular and Nervous Systems and Intestines in a Drosophila Senescence-Accelerated Model. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 1826–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi, Y.; Komura, T.; Kashima, N.; Tamura, M.; Kage-Nakadai, E.; Saeki, S.; Terao, K.; Nishikawa, Y. Influence of Oral Supplementation with Sesamin on Longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans and the Host Defense. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, G.; Li, P.; Shi, Y.; Traore, S. S.; Shi, X.; Amoah, A. N.; Cui, Z.; Lyu, Q. Sesamin Activates Skeletal Muscle FNDC5 Expression and Increases Irisin Secretion via the SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 7704–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.C.; Jinn, T.R.; Hou, R.C.W.; Tzen, J.T.C. Neuroprotective Effects of Sesamin and Sesamolin on Gerbil Brain in Cerebral Ischemia. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 2, 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.D.; Inoue, Y. H. Sesamin Activates Nrf2/Cnc-Dependent Transcription in the Absence of Oxidative Stress in Drosophila Adult Brains. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, M.; Harada, M.; Nakahara, K.; Akimoto, K.; Shibata, H.; Miki, W.; Kiso, Y. Novel Antioxidative Metabolites in Rat Liver with Ingested Sesamin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1666–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiso, Y. Antioxidative Roles of Sesamin, A Functional Lignan in Sesame Seed, and It's Effect on Lipid- and Alcohol-Metabolism in the Liver: A DNA Microarray Study. BioFactors 2004, 21, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Bohmann, D. A versatile ΦC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and Nrf2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 34063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, A. H.; Perrimon, N. Targeted Gene Expression as a Means of Altering Cell Fates and Generating Dominant Phenotypes. Development 1993, 118, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suster, M.L.; Seugnet, L.; Bate, M.; Sokolowski, M.B. Refining GAL4-driven Transgene Expression in Drosophila with a GAL80 Enhancer-trap. Genesis. 2004, 39, 240–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőw, P. , Varga, A., Pircs, K., Nagy, P., Szatmári, Z., Sass, M., Juhász, G. Impaired Proteasomal Degradation Enhances Autophagy via Hypoxia Signaling in Drosophila. BMC Cell Biol, 2013, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiri, E.N.; Gumeni, S.; Vougas, K.; Pendin, D.; Papassideri, I.; Daga, A.; Gorgoulis, V.; Juhász, G.; Scorrano, L.; Trougakos, I.P. Proteasome Dysfunction Induces Excessive Proteome Instability and Loss of Mitostasis that can be Mitigated by Enhancing Mitochondrial Fusion or Autophagy. Autophagy, 2019, 15, 1757–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, A.; Kotani, E.; Inoue, Y.H. Sesamin Exerts an Antioxidative Effect by Activating the Nrf2 Transcription Factor in the Glial Cells of the Central Nervous System in Drosophila Larvae. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velentzas, P.D.; Velentzas, A.D.; Mpakou, V.E.; Antonelou, M.H.; Margaritis, L.H.; Papassideri, I.S.; Stravopodis, D.J. Detrimental Effects of Proteasome Inhibition Activity in Drosophila melanogaster: Implication of ER Stress, Autophagy, and Apoptosis. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2013, 29, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, M.; Le, T. D.; Inoue, Y. H. Downregulating Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase γ in the Muscle Stimulated Autophagy, Apoptosis, and Muscle Aging-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila Adults. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.-K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Greenlaw, J. L.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T. W. Antioxidants Enhance Mammalian Proteasome Expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8786–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motohashi, H.; Katsuoka, F.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Small Maf Proteins Serve as Transcriptional Cofactors for Keratinocyte Differentiation in The Keap1-Nrf2 regulatory Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 6379–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G. E.; Niehueser-Saran, J.; Watson, A.; Gao, L.; Ishii, T.; De Winter, P.; Siow, C. M. Nrf2/ARE Regulated Antioxidant Gene Expression in Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells in Oxidative Stress: Implications for Atherosclerosis and Preeclampsia. Acta Physiol. Sin. 2007, 59, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gumeni, S.; Papanagnou, E.-D.; Manola, M. S.; Trougakos, I. P. Nrf2 Activation Induces Mitophagy and Reverses Parkin/Pink1 Depletion-Mediated Neuronal and Muscle Degeneration Phenotypes. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Jia, Z.; Sui, Y. Sesamin Promotes Apoptosis and Pyroptosis via Autophagy to Enhance Antitumour Effects on Murine T-Cell Lymphoma. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 147, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiela, A.; Sabater-Arcis, M.; Espinosa-Espinosa, J.; Zulaica, M.; Lopez de Munain, A.; Artero, R. Increased Muscleblind levels by Chloroquine Treatment Improve Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Phenotypes in in vitro and in vivo Models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 25203–25213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuta, S.; Nishida, H.; Ozaki, M.; Kohno, N.; Le, T. D.; Inoue, Y. H. Metformin Suppresses Progression of Muscle Aging via Activation of the AMP Kinase-Mediated Pathways in Drosophila Adults. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 8039–8056. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, H.; Yang, N.; Yi, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Sesamin Alleviates Lipid Accumulation Induced by Elaidic Acid in L02 Cells through TFEB Regulated Autophagy. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima Y, Tashiro Y, Suzuki N, Warita H, Kato M, Tateyama M, Ando R, Izumi R, Yamazaki M, Abe M, Sakimura K, Ito H, Urushitani M, Nagatomi R, Takahashi R, Aoki M. Proteasome dysfunction induces muscle growth defects and protein aggregation. J Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 5204–5217.

- Maharjan, S.; Oku, M.; Tsuda, M.; Hoseki, J.; Sakai, Y. Mitochondrial Impairment Triggers Cytosolic Oxidative Stress and Cell Death Following Proteasome Inhibition. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, A. M.; Linder, R. A.; Zhang, H.; Forman, H. J.; Davies, K. J. A. Nrf2-Dependent Induction of Proteasome and Pa28αβ Regulator Are Required for Adaptation to Oxidative Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10021–10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirin, J.; Nieuwenhuis, J.; Samsonova, A.; Tao, R.; Perrimon, N. Regulators of Autophagosome Formation in Drosophila Muscles. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Sesamin consumption does not affect Nrf2 activation in indirect flight muscles (IFMs) of Drosophila adults. (a, c, e) Stereo-fluorescence micrographs of flies with ARE-GFP reporter fed on a fly diet supplemented with DMSO for 7 days (a), 20 days (b), and 30 days (c) after eclosion (control). (b, d, f) Stereo-fluorescence micrographs of ARE-GFP flies fed on the diet supplemented with sesamin and DMSO for 7 days (b), 20 days (d), and 30 days (f) after eclosion (sesamin). Green; GFP fluorescence of indirect flight muscles (IFMs) from Drosophila adults carrying ARE-GFP reporter. (B) Quantification of GFP fluorescence in the thoraxes of flies. White bars represent the average intensities of the fluorescence of flies fed on a diet supplemented with DMSO. Gray bars: average intensities of GFP fluorescence of flies fed on a diet supplemented with sesamin and DMSO. n ≥ nine flies in each group. ns: not significant; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. The differences between controls and sesamin-fed flies are statistically not significant (p > 0.05 in each comparison).

Figure 1.

Sesamin consumption does not affect Nrf2 activation in indirect flight muscles (IFMs) of Drosophila adults. (a, c, e) Stereo-fluorescence micrographs of flies with ARE-GFP reporter fed on a fly diet supplemented with DMSO for 7 days (a), 20 days (b), and 30 days (c) after eclosion (control). (b, d, f) Stereo-fluorescence micrographs of ARE-GFP flies fed on the diet supplemented with sesamin and DMSO for 7 days (b), 20 days (d), and 30 days (f) after eclosion (sesamin). Green; GFP fluorescence of indirect flight muscles (IFMs) from Drosophila adults carrying ARE-GFP reporter. (B) Quantification of GFP fluorescence in the thoraxes of flies. White bars represent the average intensities of the fluorescence of flies fed on a diet supplemented with DMSO. Gray bars: average intensities of GFP fluorescence of flies fed on a diet supplemented with sesamin and DMSO. n ≥ nine flies in each group. ns: not significant; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. The differences between controls and sesamin-fed flies are statistically not significant (p > 0.05 in each comparison).

Figure 2.

Stimulation of autophagy in IFMs of adult Drosophila fed sesamin. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody, which is a marker to monitor the autophagy levels (green in a-f, white in a'-f') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining for myofibril visualization (red in a-f). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control) for 7 days (a), 20 days (c), and 30 days (e) after eclosion (control), and fed on sesamin with DMSO for 7 days (b), 20 days (d) and 30 days (f) after eclosion (sesamin). (B) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs. n > 10 images (n > 10 flies) in each group. ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant; One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. The differences between controls and sesamin-fed flies for 30 days are statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Stimulation of autophagy in IFMs of adult Drosophila fed sesamin. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody, which is a marker to monitor the autophagy levels (green in a-f, white in a'-f') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining for myofibril visualization (red in a-f). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control) for 7 days (a), 20 days (c), and 30 days (e) after eclosion (control), and fed on sesamin with DMSO for 7 days (b), 20 days (d) and 30 days (f) after eclosion (sesamin). (B) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs. n > 10 images (n > 10 flies) in each group. ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant; One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. The differences between controls and sesamin-fed flies for 30 days are statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of the sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by the simultaneous administration of an autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ). (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody that recognizes ubiquitinated (Ub) protein aggregated (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on a diet with DMSO as a control (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d) The flies were additionally administered CQ at 1mM (CQ (c) and CQ+sesamin (d)). (B) Quantification of Ub-aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM the flies. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in IFMs of control flies (No drugs); gray bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); light pink bar, the numbers in IFMs of CQ-fed flies (CQ); pink bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin- and CQ-fed flies (CQ+sesamin). n ≥ 13 images (≥ 13 flies). *p<0.05, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of the sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by the simultaneous administration of an autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ). (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody that recognizes ubiquitinated (Ub) protein aggregated (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on a diet with DMSO as a control (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d) The flies were additionally administered CQ at 1mM (CQ (c) and CQ+sesamin (d)). (B) Quantification of Ub-aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM the flies. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in IFMs of control flies (No drugs); gray bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); light pink bar, the numbers in IFMs of CQ-fed flies (CQ); pink bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin- and CQ-fed flies (CQ+sesamin). n ≥ 13 images (≥ 13 flies). *p<0.05, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 4.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregates is attenuated by the flies harboring the adult muscle-specific depletion of Atg8, essential for autophagy. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control (a, c)), and on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Atg8 (Mef2 > Atg8RNAi). (B) Quantification of Ub- aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on a diet with DMSO (control); gray bar, the numbers in sesamin- and DMSO-fed control flies (sesamin); light green bar, the numbers in flies harboring the Atg8 depletion (Mef2 > Atg8RNAi) fed on DMSO (control); green bar, the numbers in sesamin- and DMSO- fed flies harboring the Atg8 depletion (sesamin). n > 18 images (n > 18 flies) in each group. *p<0.05, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 4.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregates is attenuated by the flies harboring the adult muscle-specific depletion of Atg8, essential for autophagy. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control (a, c)), and on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Atg8 (Mef2 > Atg8RNAi). (B) Quantification of Ub- aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on a diet with DMSO (control); gray bar, the numbers in sesamin- and DMSO-fed control flies (sesamin); light green bar, the numbers in flies harboring the Atg8 depletion (Mef2 > Atg8RNAi) fed on DMSO (control); green bar, the numbers in sesamin- and DMSO- fed flies harboring the Atg8 depletion (sesamin). n > 18 images (n > 18 flies) in each group. *p<0.05, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 5.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregates in the IFMs is not affected in the flies administered a proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d) The flies were additionally administered bortezomib (BZ) (BZ (c)) (BZ+sesamin (d)) for the same period. (B) Quantification of ubiquitinated protein aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM of the flies. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control flies fed on DMSO (No drugs); gray bar, the numbers in sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); light pink bar, the numbers in BZ-fed flies (BZ); purple bar, the numbers in sesamin- and BZ-fed flies (BZ+sesamin). n ≥ 13 images (≥ 13 flies). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 5.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregates in the IFMs is not affected in the flies administered a proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib. (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d) The flies were additionally administered bortezomib (BZ) (BZ (c)) (BZ+sesamin (d)) for the same period. (B) Quantification of ubiquitinated protein aggregates per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM of the flies. Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control flies fed on DMSO (No drugs); gray bar, the numbers in sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); light pink bar, the numbers in BZ-fed flies (BZ); purple bar, the numbers in sesamin- and BZ-fed flies (BZ+sesamin). n ≥ 13 images (≥ 13 flies). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 6.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregate is not affected in the flies harboring the adult muscle-specific depletion of a 19S proteasome component, Rpn11, or a 20S proteasome component, Prosβ1. (A, C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control, (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (b, d) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (B, D) Quantification of ubiquitinated protein aggregates per confocal microscopic field in the IFM. (B) Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in IFMs of control (Mef2 > +) flies (control); gray bar; the numbers in sesamin-fed flies without depletion (Mef2 > +)(sesamin); beige bar, the numbers in flies harboring the Rpn11 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (control); orange bar, the numbers in sesamin-fed flies harboring the Rpn11 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 12 images (≥ 12 flies). *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. (C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). The flies were fed on DMSO (a, c) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (b, d) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Prosβ1 (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi). (D) Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control (Mef2 > +) flies (control); gray bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); light blue bar, the numbers in IFMs of flies harboring the Prosβ1 depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (control); blue bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Prosβ1 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 12 images (≥ 12 flies). ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 6.

The sesamin’s effect in promoting the elimination of Ub-aggregate is not affected in the flies harboring the adult muscle-specific depletion of a 19S proteasome component, Rpn11, or a 20S proteasome component, Prosβ1. (A, C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control, (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (b, d) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (B, D) Quantification of ubiquitinated protein aggregates per confocal microscopic field in the IFM. (B) Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in IFMs of control (Mef2 > +) flies (control); gray bar; the numbers in sesamin-fed flies without depletion (Mef2 > +)(sesamin); beige bar, the numbers in flies harboring the Rpn11 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (control); orange bar, the numbers in sesamin-fed flies harboring the Rpn11 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 12 images (≥ 12 flies). *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. (C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with FK2 antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). The flies were fed on DMSO (a, c) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (b, d) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Prosβ1 (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi). (D) Light gray bar, average numbers of Ub-aggregates in control (Mef2 > +) flies (control); gray bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); light blue bar, the numbers in IFMs of flies harboring the Prosβ1 depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (control); blue bar, the numbers in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Prosβ1 depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 12 images (≥ 12 flies). ****p<0.0001, ns: not significant. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 7.

Maintenance of the sesamin’s effect that stimulates the autophagy in IFMs of flies by administration of bortezomib (BZ). (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d)The flies were additionally administered BZ (BZ (c), BZ+sesamin (d)). (B) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs of the flies. Light gray bar, average units of Ref(2)P signals in IFMs of control flies (No drugs); gray bar, the units in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); pink bar, the units in IFMs of BZ-fed flies (BZ); purple bar, the units in IFMs of BZ- and sesamin- fed flies (BZ+sesamin). n ≥15 images (≥ 15 flies) in each group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 7.

Maintenance of the sesamin’s effect that stimulates the autophagy in IFMs of flies by administration of bortezomib (BZ). (A) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (No drugs (a)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b)) for 20 days after eclosion. (c, d)The flies were additionally administered BZ (BZ (c), BZ+sesamin (d)). (B) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs of the flies. Light gray bar, average units of Ref(2)P signals in IFMs of control flies (No drugs); gray bar, the units in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies (sesamin); pink bar, the units in IFMs of BZ-fed flies (BZ); purple bar, the units in IFMs of BZ- and sesamin- fed flies (BZ+sesamin). n ≥15 images (≥ 15 flies) in each group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 8.

Maintenance of the sesamin’s effect that stimulates the autophagy in IFMs of flies harboring adult muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 or Prosβ1. (A, C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control, (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (C, D) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs of the flies. (C) The flies were fed on DMSO (control (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (B, D) Quantification of Ref(2)P signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM. (B) Light gray bar, average amount of Ref(2)P signals (units) in IFMs of control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on DMSO (control); gray bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); beige bar, the signals in IFMs of flies harboring the Rpn11depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (control); orange bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Rpn11depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 14 images (n≥ 14 flies) in each genotype. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. (D) Light gray bar, the average amount of Ref(2)P signals (units) in IFMs of control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on DMSO (control); gray bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); light blue bar, the signals in IFMs of flies harboring the Prosβ1depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (control); blue bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Prosβ1depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 14 images (n≥ 14 flies) in each genotype. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 8.

Maintenance of the sesamin’s effect that stimulates the autophagy in IFMs of flies harboring adult muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 or Prosβ1. (A, C) Confocal micrographs of IFMs immunostained with anti-Ref(2)P antibody (green in a-d, white in a'-d') and Alexa 488-phalloidin staining (red in a-d). (A) The flies were fed on DMSO (control, (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (C, D) Quantification of anti-Ref(2)P immunostaining signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFMs of the flies. (C) The flies were fed on DMSO (control (a, c)) and fed on sesamin with DMSO (sesamin (b, d)) for 20 days after eclosion. (a, b) Control flies without the depletion (Mef2 > +). (c, d) Flies harboring the muscle-specific depletion of Rpn11 (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi). (B, D) Quantification of Ref(2)P signals (units) per a confocal microscopic field in the IFM. (B) Light gray bar, average amount of Ref(2)P signals (units) in IFMs of control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on DMSO (control); gray bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); beige bar, the signals in IFMs of flies harboring the Rpn11depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (control); orange bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Rpn11depletion (Mef2 > Rpn11RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 14 images (n≥ 14 flies) in each genotype. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. (D) Light gray bar, the average amount of Ref(2)P signals (units) in IFMs of control flies (Mef2 > +) fed on DMSO (control); gray bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies without depletion (sesamin); light blue bar, the signals in IFMs of flies harboring the Prosβ1depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (control); blue bar, the signals in IFMs of sesamin-fed flies harboring the Prosβ1depletion (Mef2 > Prosβ1RNAi) (sesamin). n ≥ 14 images (n≥ 14 flies) in each genotype. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ns: not significant. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).