1. Introduction

Aging is accompanied by a progressive decline in neuromuscular function, which leads to changes in gait patterns and an increased risk of falls [

1,

2,

3]. In particular, reduced ankle strength and diminished proprioceptive sensitivity contribute to decreased propulsive force during terminal stance, which not only slows walking speed but also increases energy expenditure [

4,

5]. To compensate for this, older adults tend to rely more on proximal joints, such as the hip, further reducing gait efficiency [

6,

7].

Among older adults, women are at greater risk. Postmenopausal estrogen decline accelerates the loss of muscle mass and strength, making older women more vulnerable to gait dysfunction and falls compared to men [

8,

9]. Furthermore, from the age of 60, the decline in walking speed accelerates, and gait efficiency significantly deteriorates [

10,

11].

According to previous studies, restoring ankle strategy—namely, generating propulsive force from distal segments—is critical for maintaining efficient gait in older adults [

7,

12]. However, traditional resistance or balance training programs, often performed in stable environments, lack the sensory-motor integration stimuli required for actual walking, limiting their ability to induce neuromuscular adaptations or functional joint-level changes [

13,

14].

Training using water inertia load offers unpredictable resistance as the water shifts, providing both proprioceptive stimulation and reactive control challenges [

15,

16]. Repeated exposure to such perturbations may enhance neuromuscular coordination and stability around the ankle joint, thereby improving propulsive force during gait [

17,

18,

19].

Nevertheless, little is known about the effects of water inertia-based training on biomechanical parameters, such as the redistribution of lower limb joint moments or the generation of positive mechanical work during walking. In order to clarify the mechanisms underlying effective propulsion strategies in older adults, it is necessary to go beyond spatiotemporal variables and include quantitative analyses of joint-level force generation and energy transfer.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of a 12-week dynamic stability training program using water inertia load on spatiotemporal gait characteristics and lower limb biomechanical variables in elderly women.

The hypotheses of this study are as follows:

- (1)

The training will improve spatiotemporal parameters such as gait speed, stride length, and cadence.

- (2)

Ankle plantar flexor moment and positive mechanical work will increase, while compensatory hip moment will decrease.

These outcomes are expected to reflect the recovery of a more efficient propulsion strategy during gait.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 30 healthy elderly women aged 65 years and older were recruited for this study. Recruitment was conducted through a community center and a university located in region B. Prior to participation, all individuals received a thorough explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures, and signed written informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202409-01-034) and was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT06705946) on November 25, 2024.

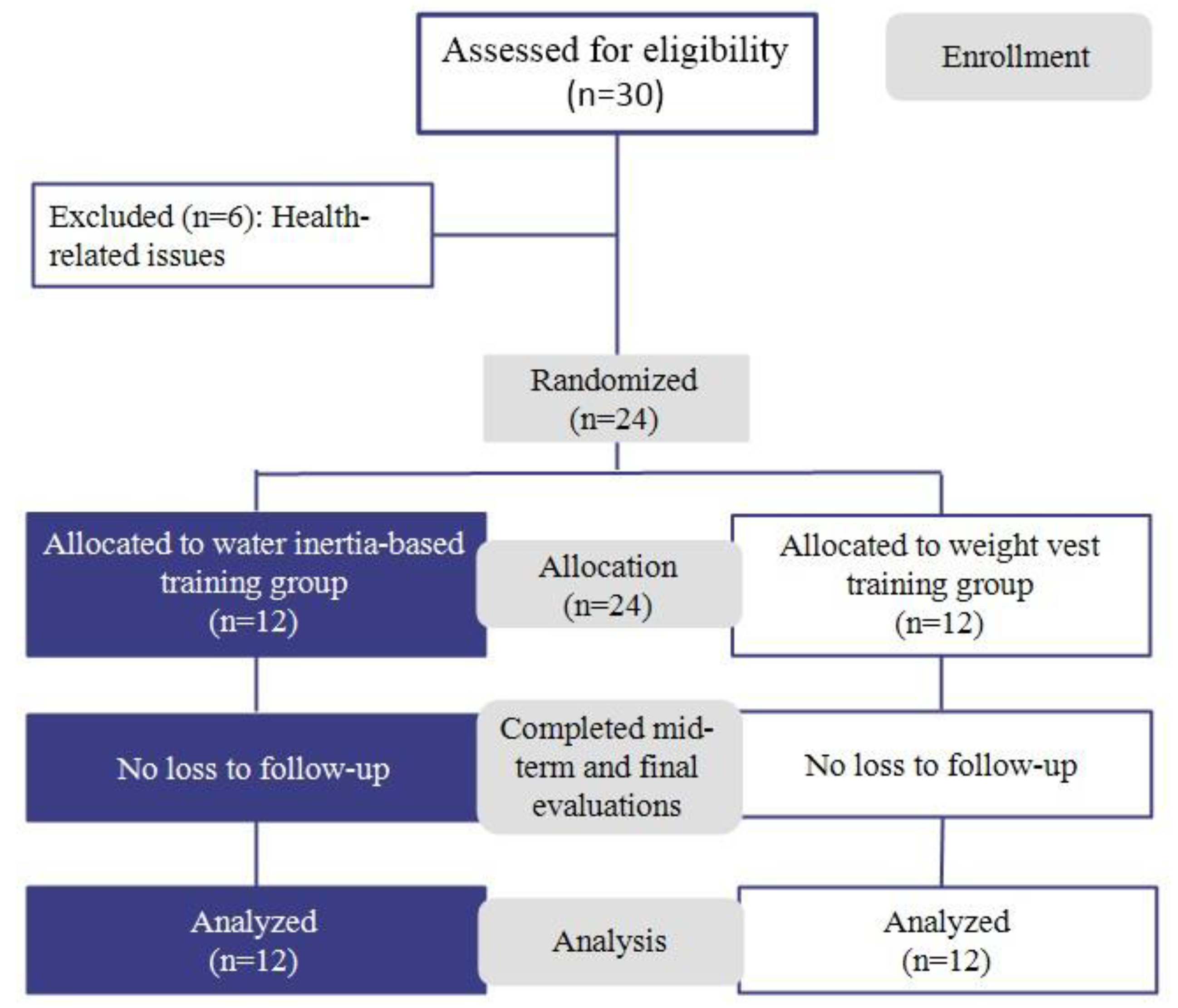

Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 15) or the control group (n = 15). After excluding 6 participants who withdrew due to health-related reasons, data from 24 participants (12 in each group) were included in the final analysis.The required sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 software based on a repeated measures ANOVA design (2 groups × 3 time points) with interaction effects. The parameters were set to an effect size of f = 0.32, α = 0.05, and statistical power (1–β) = 0.80. The results indicated that a total of 18 participants would be required, and this informed the final sample size decision. Given that 24 participants were included in the final analysis, the study secured sufficient statistical power to detect the expected effects.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

History of musculoskeletal disorders within the past 3 months

Severe cardiopulmonary diseases (e.g., heart failure, myocardial infarction)

Use of medications such as anxiolytics, antidepressants, or sedatives

Diagnosis of chronic pulmonary disease

History of surgery within the past 6 months.

Furthermore homogeneity tests confirmed that there were no significant differences between the groups in age (t = − 0.676), height (t = 0.573), weight (t = 0.810), or BMI (t = − 0.557) indicating that the baseline physical characteristics were statistically comparable. Indicating that the baseline physical characteristics were statistically comparable. Additionally, all participants confirmed that they had not engaged in any structured physical activity programs within the six months preceding the study.

Table 1 and

Figure 1 present the participants’ general characteristics and the flow diagram of participant allocation thoughout the study.

2.2. Gait Assessment and Data Acquisition

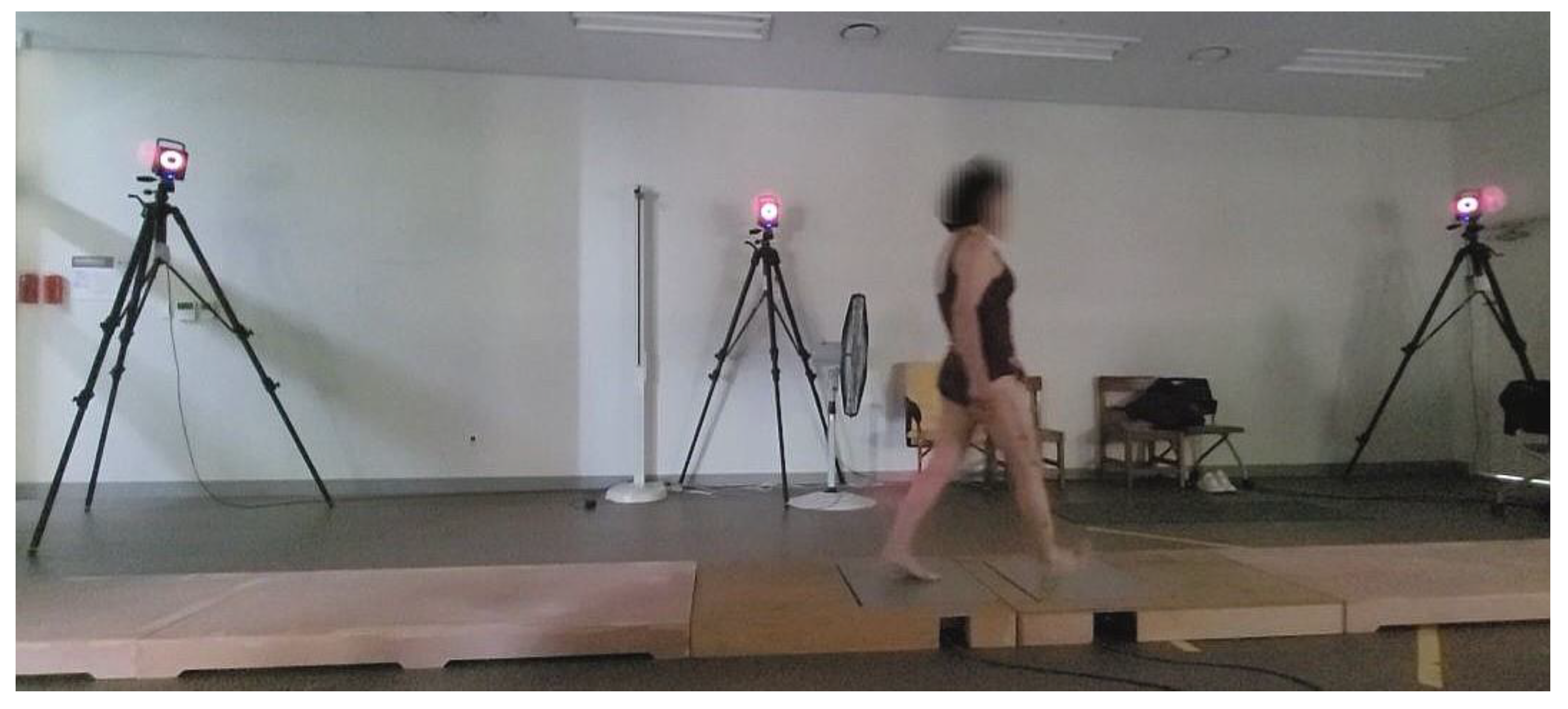

Spatiotemporal gait characteristics, a 6-meter walkway and six infrared-based three-dimensional motion capture cameras (Vicon camera MX-T20, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) were utilized [

20](

Figure 2). Gait measurements were conducted in a quiet environment with minimal external distractions. Prior to data collection, participants performed familiarization trials to adapt to the testing protocol. Each participant walked barefoot at a self-selected, comfortable pace, and six trials were recorded. Among these, three valid gait cycles were extracted and used for analysis. To enhance measurement reliability and detect subtle changes in gait velocity, all assessments were repeated under identical conditions (Peters et al., 2013). Reflective markers were placed on the following anatomical landmarks: anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), mid-lateral thigh, lateral femoral epicondyle, mid-shank, lateral malleolus, head of the second metatarsal, and calcaneus. All participants wore swimwear to minimize clothing interference with the markers, and measurements were performed barefoot (Perrin et al., 2022). All kinematic and kinetic data were sampled at 100 Hz. Marker trajectories and ground reaction force data were processed using the Plug-in Gait Dynamic model based on inverse dynamics. Positive mechanical work was calculated by integrating the product of joint moment and angular velocity over time during the terminal stance phase. The analysis focused on the time point immediately prior to foot-off. All kinetic variables were normalized to each participant’s body weight and height for comparative analysis.

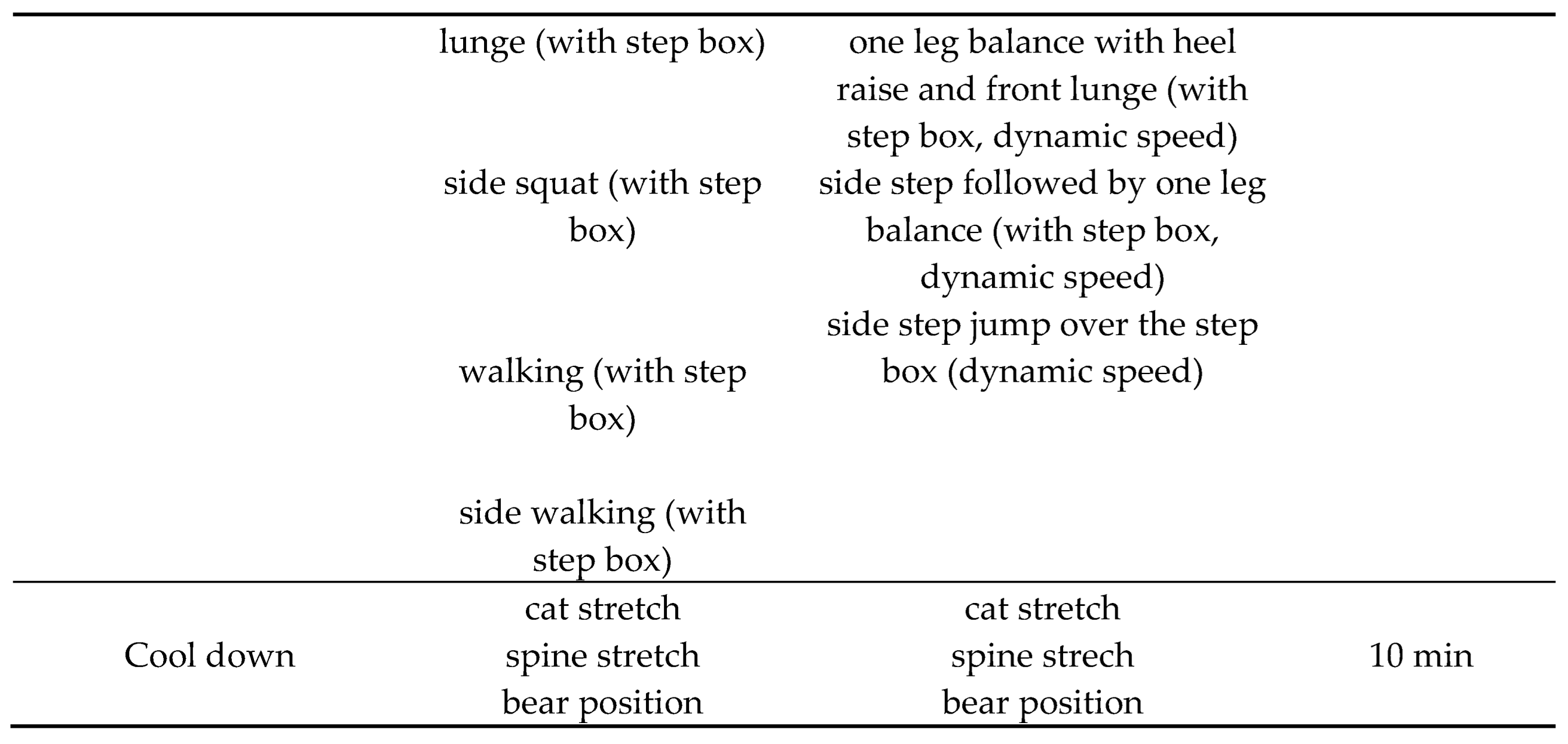

2.3. Exercise Intervention

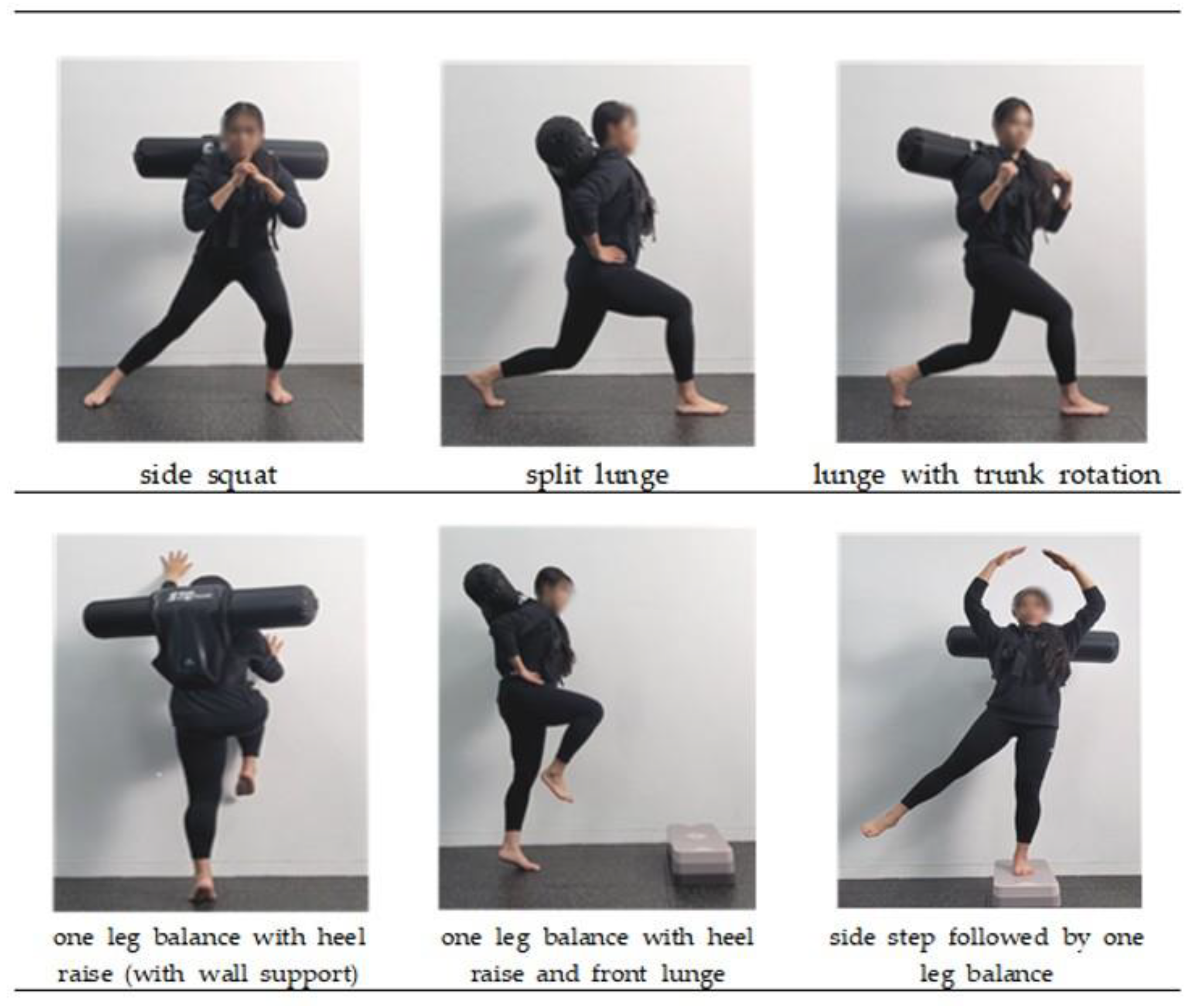

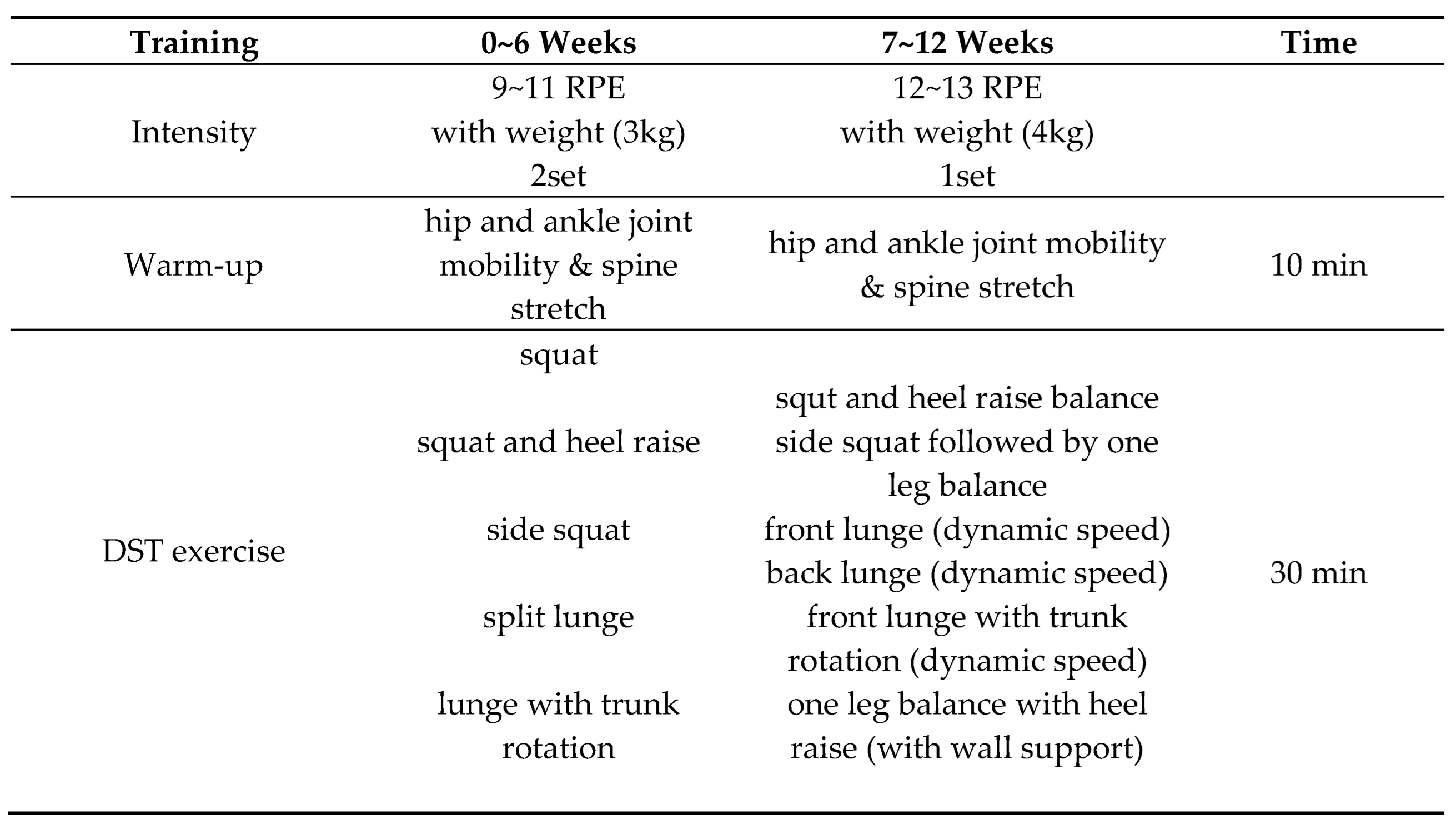

The dynamic stability training (DST) in this study was based on the Instability Neuromuscular Training program proposed by Kang and Park. [

17] and was conducted twice a week for 12 weeks, totaling 24 sessions. Each session consisted of a warm-up, main exercises, and a cool-down phase. The structure and details of the training program are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3. During weeks 1–6, participants performed low-intensity exercises focused on bilateral stance and weight shifting (RPE 9–11, 3 kg). From weeks 7–12, the program progressed to moderate-intensity exercises involving single-leg stance and balance maintenance (RPE 12–13, 4 kg). The experimental group wore an aqua vest, while the control group wore a weight vest during the same training protocol. Exercise intensity and progression were adjusted based on participants’ rating of perceived exertion (RPE)[

23,

24].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data collected in this study were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Means and standard deviations were calculated for all variables. To verify the homogeneity of demographic characteristics between groups, an independent t-test was performed. Prior to analyzing the intervention effects, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data.

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA (group × time) was used to examine the interaction effects of the intervention. When significant interaction or main effects were found, Bonferroni post hoc tests were conducted to identify differences across time points. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

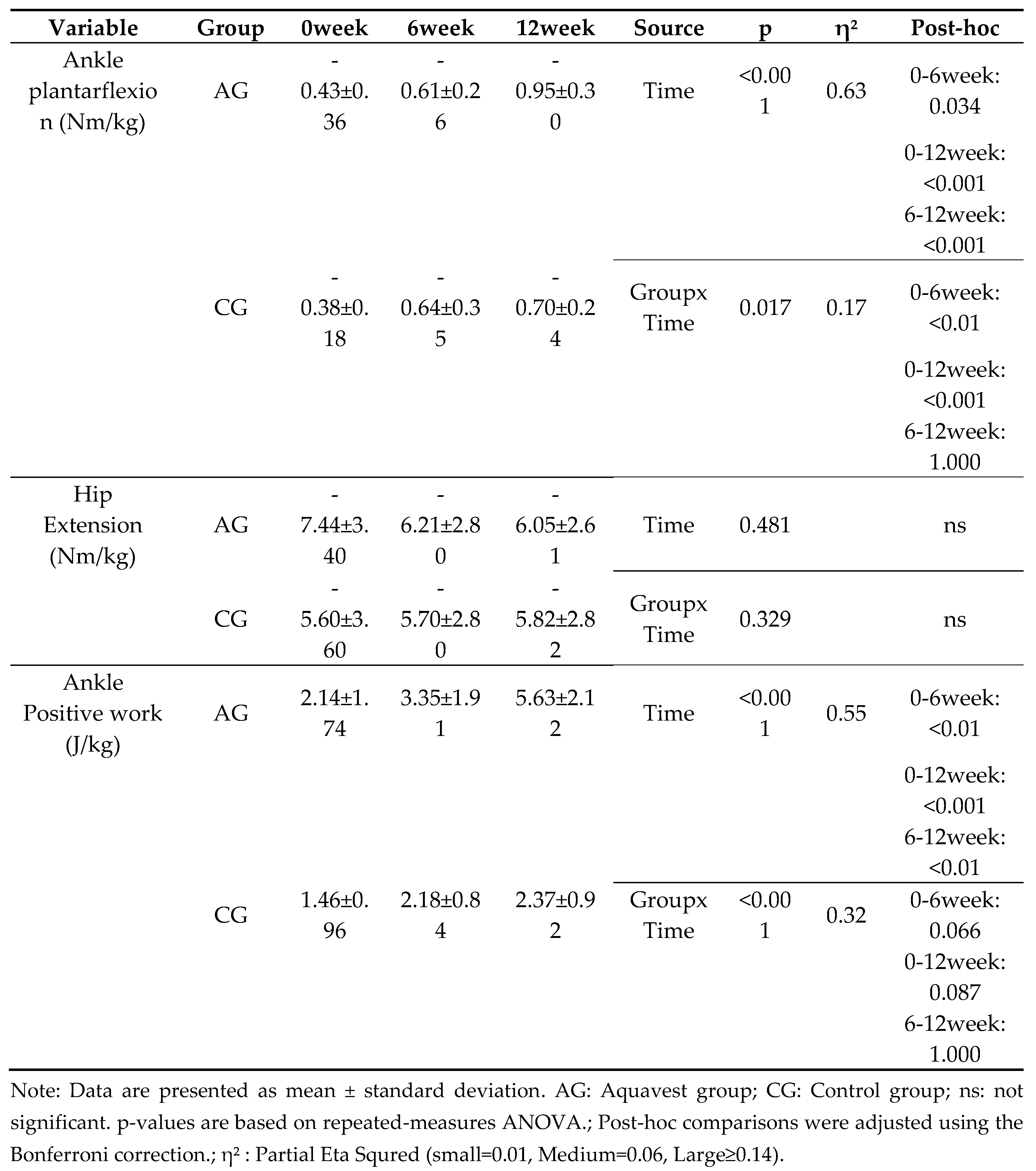

The results related to lower limb joint moments, and positive mechanical work, spatiotemporal gait parameters are presented in (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

3.1. Changes in Lower Limb Joint Moments and Ankle Positive Mechanical Work

Repeated-measures ANOVA for peak ankle plantarflexion moment demonstrated a significant main effect of time (p < 0.001, η² = 0.63) and a significant time × group interaction (p = 0.017, η² = 0.17). Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc comparisons in the aqua vest group revealed significant improvements across all time intervals (0–6 weeks: p = 0.034; 0–12 weeks: p < 0.001; 6–12 weeks: p < 0.001). In the control group, significant differences were found between 0–6 weeks (p < 0.01) and 0–12 weeks (p <0 .001), whereas no significant difference was observed between 6–12 weeks (p = 1.000).

For peak hip extension moment, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied due to a violation of sphericity. No significant main effect of time (p = 0.481) or time × group interaction (p = 0.329) was observed.

In ankle positive mechanical work, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied due to the violation of sphericity. A significant main effect of time was found (p < 0.001, η² = 0.55), as well as a significant time × group interaction (p < 0.001, η² = 0.32). Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc tests in the aquavest group revealed significant differences between all time points (0–6 weeks: p < 0.01; 0–12 weeks: p < 0.001; 6–12 weeks: p <0 .01), whereas the control group showed no significant differences at any time point (all p > 0.05).

3.2. Change in Gait Parameters

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects of time for all gait parameters—cadence, stride length, and gait speed (p < 0.001; η² = 0.33, 0.68, and 0.73, respectively). A significant time × group interaction was found for stride length (p < 0.001, η² = 0.35) and gait speed (p < 0.001, η² = 0.32), but not for cadence (p = 0.818, η² = 0.01).

Bonferroni post-hoc analyses showed that the Aqua Vest group exhibited significant improvements at all time points (0–6 weeks, 0–12 weeks, and 6–12 weeks) in stride length and gait speed, while for cadence, a significant increase was observed only between 0 and 12 weeks (p = 0.020).

In contrast, the control group showed significant changes in all three parameters only from 0 to 12 weeks, with no significant differences between 6 and 12 weeks (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects of training with water inertia load on gait control by focusing on changes in lower limb joint moments during gait in older women. Age-related decline in neural function reduces gait automaticity and increases the need for neural resources to maintain balance, resulting in slower walking speed and greater energy expenditure [

7,

25,

26]. These changes highlight the need for interventions to support efficient gait in older adults.The Aqua Vest provides unpredictable directional loading due to the free movement of water inside the device during motion, thereby demanding a higher level of dynamic balance control than traditional weight-based loading [

27,

28]. This type of dynamic resistance effectively stimulates neuromuscular control and sensorimotor feedback, contributing to improved balance strategies during walking [

17,

18]. Indeed, in the present study, the Aqua Vest group showed significantly greater improvements in gait control ability compared to the weight vest group.

Changes in lower limb joint moments served as a key indicator in explaining modifications in gait strategy. In the Aqua Vest group, the ankle plantarflexion moment significantly increased over time, while the hip extension moment showed a decreasing trend. This contrasts with the typical age-related pattern of diminished ankle strategy and increased compensatory reliance on the hip [

12,

29], suggesting a partial restoration of inter-joint moment balance. Mackey and Robinovitch. [

30] reported that in older women, neural response speed is more critical than ankle strength for balance recovery, which is associated with reduced signal transmission at the spinal level and decreased motor unit recruitment [

31]. Additionally, Franz. [

25] found that faster contraction velocity of the plantarflexors leads to greater moment generation at foot-off, supporting the current findings. Moreover, the training program in this study included exercises such as side steps, side squats, and split lunges, which likely facilitated coordination between the ankle and hip musculature and improved the speed and stability of weight shifting [

17,

32]. Older adults often exhibit delayed weight transfer due to weakened hip abductor and adductor function (Porto et al., 2019), and this intervention may have helped compensate for such limitations. Lanza et al. [

34] also reported that faster neuromuscular activation of hip muscles is associated with shorter weight transfer times, suggesting that the current training may have been effective in enhancing reflexive responses and inter-joint coordination. In contrast, the control group trained under a predictable and fixed load environment, which likely limited sensorimotor feedback and neuromuscular activation. This aligns with previous studies showing that adaptation responses are reduced in predictable training conditions [

35,

36]. Indeed, the control group showed significant improvements only between 0–6 weeks and 0–12 weeks, with no further gains observed from 6 to 12 weeks, indicating that unpredictable load characteristics may be critical for sustained neuromuscular adaptation.

An increase in positive work generated at the ankle joint is interpreted as a key indicator of enhanced propulsion and improved energy efficiency during gait. In the Aqua Vest group, positive work significantly increased across all time points, reflecting a strengthening of the ankle strategy and a reduced reliance on compensatory hip involvement. During gait, as body weight transfers from one limb to the other, the leading leg absorbs the impact while the trailing leg generates propulsion to counterbalance it. When propulsion at foot-off is insufficient, energy loss increases, ultimately reducing gait efficiency [

37]. From this perspective, the increase in positive ankle work observed in the Aqua Vest group suggests improvements in weight transfer and propulsion strategies, which subsequently led to enhanced gait speed, step length, and rhythm stability. Indeed, the Aqua Vest group demonstrated significant improvements in cadence, gait velocity, and step length, with an average gait speed increase of 0.19 m/s—exceeding the threshold for clinically meaningful change (≥0.10 m/s) [

38]. In contrast, the control group showed a smaller increase of 0.08 m/s, indicating a more limited level of neuromuscular adaptation.

Gait speed is determined by a combination of cadence and stride length, both of which are closely related to neuromuscular control, balance maintenance, and propulsion generation [

39]. Older adults, due to reduced muscle strength and difficulty maintaining balance, tend to prefer increasing cadence over stride length as a strategy to improve gait speed [

40]. In the present study, weight-shifting tasks such as front lunges and side walking were included as part of the training. These movements are similar to the muscle activation strategies used during the late stance phase of gait [

41], requiring both forward propulsion and stability during landing. Such exercises likely enhanced the ability to shift the center of mass forward, contributing to increased stride length. In particular, performing these weight-shifting tasks under irregular perturbation conditions likely demanded a higher level of balance control and neuromuscular response in the Aqua Vest group. The progressive increase in task difficulty and load after week 6 of training further stimulated improvements in response speed. These adaptations are thought to have played a key role in improving stride length during the latter part of the gait cycle [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Additionally, the non-linear loading stimuli provided by the training induced repeated contraction and relaxation of the ankle muscles, which enhanced reaction speed and inter-joint coordination. This improvement in the weight transfer strategy—from single-leg support to contralateral propulsion—likely contributed to the observed increases in gait speed and stride length. Kim et al. [

46] also reported that older women with higher gait speeds tend to exhibit better muscular function and greater gait consistency, which aligns with the observed improvements in gait speed and rhythm control in the Aqua Vest group in this study.

Therefore, training with water inertia load may effectively contribute to the restoration of ankle-based strategies and serve as a valuable intervention for improving gait function in older adults. However, the reduction in ipsilateral hip moment was not substantial, which may reflect the inherent difficulty older adults have in modifying established gait patterns. Fukuchi et al. [

47] reported that older individuals tend to maintain their habitual motor strategies even when gait speed increases. This phenomenon is likely due to the slower rate of neuromuscular adaptation and the long-term habituation of movement patterns. Accordingly, to facilitate more efficient coordination between the ankle and hip joints, long-term approaches or training strategies specifically targeting inter-joint coordination may need to be incorporated.

This study was conducted based on two primary hypotheses, and the results largely supported both. First, the Aqua Vest group showed significant improvements in most spatiotemporal gait variables, including gait speed, stride length, and cadence, indicating that the training effectively enhanced gait rhythm and propulsion. Second, the ankle plantarflexion moment and positive mechanical work significantly increased over time, while the compensatory hip moment tended to decrease. However, the reduction appears to have been insufficient, suggesting that the distribution of joint loading across the lower limbs may have shifted toward a more efficient pattern. These findings generally support the two hypotheses proposed in this study and demonstrate that training with water inertia load can have a positive impact on gait strategies and joint biomechanics in older adults.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the effects of dynamic stability training using water inertia load on gait strategies and lower limb joint biomechanics in older women. The results demonstrated improvements in spatiotemporal gait variables, functional recovery of the ankle joint, and a more efficient distribution of joint moments across the lower limbs.These findings suggest that restoring the ankle strategy has a meaningful impact on gait efficiency and propulsion, highlighting the clinical applicability of this intervention. Furthermore, the two hypotheses proposed in this study—(1) improvements in gait speed, stride length, and cadence, and (2) increased ankle plantarflexion moment and positive mechanical work with a reduction in compensatory hip moment—were generally supported. This indicates that training with water inertia load can contribute to enhancing gait strategies in older adults. However, the reduction in hip joint moment was limited, highlighting the need for future studies to develop long-term and structured intervention programs aimed at improving inter-joint coordination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and H.K.; methodology, I.P. and H.K.; software, H.K.; validation, H.K.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, H.K.; data curation, H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K and I.P.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, H.K. and I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Public Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202409-01-034, approval date: 20 September 2024). In addition, the study was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT06705946, registration date: 25 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon reasonable request and will be deposited in a public repository upon publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Minji Son for her expert guidance and meticulous support in the use of experimental equipment for this study. We also thank our fellow doctoral students for their invaluable academic discussions and for sharing knowledge that contributed to the advancement of this research. Above all, we are deeply grateful to Professor Il Bong Park for his unwavering support and insightful supervision throughout the course of this study. This manuscript is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation.

References

- Studenski S., Perera S., Patel K., Rosano C., Faulkner K., Inzitari M., Brach .J, Chandler J., Cawthon P., Connor E.B., Nevitt M., Visser M., Kritchevsky S., Badinelli S., Harris T., Newman A.B., Cauley J., Ferrucci L., Guralnik J. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50-8. [CrossRef]

- Minneci C., Mello A.M., Mossello E., Baldasseroni S., Macchi L., Cipolletti ., Marchionni N., Di Bari M. Comparative study of four physical performance measures as predictors of death, incident disability, and falls in unselected older persons: the insufficienza Cardiaca negli Anziani Residenti a Dicomano Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):136-41. [CrossRef]

- Newman A.B., Visser M., Kritchevsky S.B., Simonsick E., Cawthon P.M., Harris T.B. The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study-Ground-Breaking Science for 25 Years and Counting. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023;78(11):2024-2034. [CrossRef]

- Schrack J.A., Simonsick E.M., Chaves P.H., Ferrucci L. The role of energetic cost in the age-related slowing of gait speed. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1811-6. [CrossRef]

- Schrack J.A., Zipunnikov V., Simonsick E.M., Studenski S., Ferrucci L. Rising Energetic Cost of Walking Predicts Gait Speed Decline With Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(7):947-53. [CrossRef]

- Anderson D.E., Madigan M.L. Healthy older adults have insufficient hip range of motion and plantar flexor strength to walk like healthy young adults. J Biomech. 2014;47(5):1104-9. [CrossRef]

- Boyer K.A., Johnson R.T., Banks J.J., Jewell C., Hafer J.F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of gait mechanics in young and older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2017;95:63-70. [CrossRef]

- Das S.K., Farooqi A. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(4):657-75. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk K., Wiszomirska I., Błażkiewicz M., Wychowański M., Wit A. First signs of elderly gait for women. Med Pr. 2017 ;68(4):441-448. English. [CrossRef]

- 10. Phinyomark A, Osis S.T., Hettinga B.A., Kobsar D., Ferber R. Gender differences in gait kinematics for patients with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:157. [CrossRef]

- Noce Kirkwood R., de Souza Moreira B., Mingoti S.A., Faria B.F., Sampaio R.F., Alves Resende R. The slowing down phenomenon: What is the age of major gait velocity decline? Maturitas. 2018;115:31-36. [CrossRef]

- Buddhadev H.H., Smiley A.L., Martin P.E. Effects of age, speed, and step length on lower extremity net joint moments and powers during walking. Hum Mov Sci. 2020;71:102611. [CrossRef]

- Song S., Geyer H. Predictive neuromechanical simulations indicate why walking performance declines with ageing. J Physiol. 2018;596(7):1199-1210. [CrossRef]

- Kim H.K., Chou L.S. Lower limb muscle activation in response to balance-perturbed tasks during walking in older adults: A systematic review. Gait Posture. 2022;93:166-176. [CrossRef]

- Kurpiers N., Rovelli T., Bormann C., Vogler T. Effects of a slashpipe training intervention on postural control compared to conventional barbell power fitness. Int J Sports Exerc Med. 2018 4, 088.

- Mansfield A., Danells C.J., Inness E.L., Musselman K., Salbach N.M. A survey of Canadian healthcare professionals’ practices regarding reactive balance training. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(7):787-800. [CrossRef]

- Kang S., Park I. Effects of Instability Neuromuscular Training Using an Inertial Load of Water on the Balance Ability of Healthy Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2024;9(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Kang S., Park I., Ha M.S. Effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training using the inertial load of water on functional movement and postural sway in middle-aged women: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2024;24(1):154. [CrossRef]

- Rizzato A., Bozzato M., Rotundo L., Zullo G., De Vito G., Paoli A., Marcolin G. Multimodal training protocols on unstable rather than stable surfaces better improve dynamic balance ability in older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2024;21(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Pfister A., West A.M., Bronner S., Noah J.A. Comparative abilities of Microsoft Kinect and Vicon 3D motion capture for gait analysis. J Med Eng Technol. 2014;38(5):274-80. [CrossRef]

- Peters D.M., Fritz S.L., Krotish D.E. Assessing the reliability and validity of a shorter walk test compared with the 10-Meter Walk Test for measurements of gait speed in healthy, older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013;36(1):24-30. [CrossRef]

- Perrin T.P., Morio C.Y.M., Besson T., Kerhervé H.A., Millet G.Y., Rossi J. Comparison of skin and shoe marker placement on metatarsophalangeal joint kinematics and kinetics during running. J Biomech. 2023;146:111410. [CrossRef]

- Borg G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377-81.

- Tiggemann C.L., Pietta-Dias C., Schoenell M.C.W., Noll M., Alberton C.L., Pinto R.S., Kruel L.F.M. Rating of Perceived Exertion as a Method to Determine Training Loads in Strength Training in Elderly Women: A Randomized Controlled Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7892. [CrossRef]

- Franz J.R. The Age-Associated Reduction in Propulsive Power Generation in Walking. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2016;44(4):129-36. [CrossRef]

- Delabastita T., Hollville .E, Catteau A., Cortvriendt P., De Groote F., Vanwanseele B. Distal-to-proximal joint mechanics redistribution is a main contributor to reduced walking economy in older adults. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(5):1036-1047. [CrossRef]

- Glass S.C., Blanchette T.W., Karwan L.A., Pearson S.S., OʼNeil A.P., Karlik D.A. Core Muscle Activation During Unstable Bicep Curl Using a Water-Filled Instability Training Tube. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(11):3212-3219. [CrossRef]

- Glass S.C., Wisneski K.A. Effect of Instability Training on Compensatory Muscle Activation during Perturbation Challenge in Young Adults. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2023 Sep 15;8(3):136. [CrossRef]

- Arnold J.B., Mackintosh S., Jones S., Thewlis D. Differences in foot kinematics between young and older adults during walking. Gait Posture. 2014;39(2):689-94. [CrossRef]

- Mackey D.C., Robinovitch S.N. Mechanisms underlying age-related differences in ability to recover balance with the ankle strategy. Gait Posture. 2006 ;23(1):59-68. [CrossRef]

- Hunter S.K., Pereira H.M., Keenan K.G. The aging neuromuscular system and motor performance. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2016 ;121(4):982-995. [CrossRef]

- Boudreau S.N., Dwyer M.K., Mattacola C.G., Lattermann C., Uhl T.L., McKeon J.M. Hip-muscle activation during the lunge, single-leg squat, and step-up-and-over exercises. J Sport Rehabil. 2009;18(1):91-103. [CrossRef]

- Porto J.M., Freire Júnior R.C., Bocarde L., Fernandes J.A., Marques N.R., Rodrigues N.C., de Abreu D.C.C. Contribution of hip abductor-adductor muscles on static and dynamic balance of community-dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019 ;31(5):621-627. [CrossRef]

- Lanza M.B., Addison O., Ryan A.S., J Perez W., Gray V. Kinetic, muscle structure, and neuromuscular determinants of weight transfer phase prior to a lateral choice reaction step in older adults. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2020;55:102484. [CrossRef]

- Horslen B.C., Murnaghan C.D., Inglis J.T., Chua R., Carpenter M.G. Effects of postural threat on spinal stretch reflexes: evidence for increased muscle spindle sensitivity? J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(4):899-906. [CrossRef]

- van Dieën J.H., van Leeuwen M., Faber G.S. Learning to balance on one leg: motor strategy and sensory weighting. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114(5):2967-82. [CrossRef]

- Zelik K.E., Adamczyk P.G. A unified perspective on ankle push-off in human walking. J Exp Biol. 2016;219(Pt 23):3676-3683. [CrossRef]

- Hortobágyi T., Lesinski M., Gäbler M., VanSwearingen J.M., Malatesta D., Granacher U. Erratum to: Effects of Three Types of Exercise Interventions on Healthy Old Adults’ Gait Speed: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(3):453. [CrossRef]

- Ardestani M.M., Ferrigno C., Moazen M., Wimmer M.A. From normal to fast walking: Impact of cadence and stride length on lower extremity joint moments. Gait Posture. 2016;46:118-25. [CrossRef]

- Bogen B., Moe-Nilssen R., Ranhoff A.H., Aaslund M.K. The walk ratio: Investigation of invariance across walking conditions and gender in community-dwelling older people. Gait Posture. 2018;61:479-482. [CrossRef]

- Okubo Y., Schoene D., Lord S.R. Step training improves reaction time, gait and balance and reduces falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(7):586-593. [CrossRef]

- Peters R.M., Dalton B.H., Blouin J.S., Inglis J.T. Precise coding of ankle angle and velocity by human calf muscle spindles. Neuroscience. 2017;349:98-105. [CrossRef]

- Damulin I.V. Izmeneniia khod’by pri starenii [Changes in walking in the elderly]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2018;118(2):100-104. Russian. [CrossRef]

- Henry M., Baudry S. Age-related changes in leg proprioception: implications for postural control. J Neurophysiol. 2019 ;122(2):525-538. [CrossRef]

- Okubo Y., Schoene D., Caetano M.J., Pliner E.M., Osuka Y., Toson B., Lord S.R. Stepping impairment and falls in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of volitional and reactive step tests. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;66:101238. [CrossRef]

- Kim B., Youm C., Park H., Lee M., Choi H. Association of Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength, and Muscle Function with Gait Ability Assessed Using Inertial Measurement Unit Sensors in Older Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9901. [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi .CA, Fukuchi RK, Duarte M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):153. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).