I. Introduction

The discoveries of biochemists in the first half of the 20th Century have enabled biologists to reduce living systems to their constituent molecules. Beyond its molecules, however, the adaptive immune system is organized to learn from experience [

1]. This paper analyzes immune learning as a form of natural machine learning (NML). The approach is based on concepts of immune networks [

2] and immune computation [

3], and Sol Efroni and I have proposed that the immune system acts through crowd wisdom and machine learning [

4]. Machine learning is used by computational biology scientists to analyze immunological data [

5]. This article, however, reasons that the development of the adaptive immune system involves a biological process of natural machine learning. The paper uses terms suggestive of teleology such as needs, problems, and prompts only as aids to understanding; such terms are not meant to imply purpose or design. Nature just is [

6].

What Does the Immune System Have to Learn?

Learning may be defined as the acquisition of a new skill or new knowledge [

7]. According to the classical paradigm of clonal selection formulated by Burnet [

8], the developing immune system need only learn to recognize antigens by randomly generated antigen-receptor repertoires of lymphocyte clones and antibodies. This paradigm assumes that the immune system must ignore the self, so receptors interacting strongly with self-antigens are proposed to be deleted during lymphocyte development. Consequently, any antigen epitope recognized by mature lymphocytes or antibodies is “foreign” by definition and will activate an effector immune response free of the danger of autoimmune disease. But clonal selection, however necessary, is not sufficient to account for what we have now learned about the operations of the mature immune system [

9]: the healthy immune system does interact with the self [

10] , accommodates not-self microbiomes [

11], and generates diverse phenotypes [

12]. NML enables the immune system to compute immune phenotypes.

Immune Computation

Computation may be defined as the conversion of input into output using a defined, repeatable process [

3]. The inputs into the immune system computer are detected by the receptors of antibodies and immune system cells, innate and adaptive. The input reflects the local and general states of the body – health, infection, injury, cancer, and more – and the outputs of the immune computer are response states of the immune system – changes in cell and antibody repertoires, cell proliferations, inflammation, healing, rejection, metabolic adjustments, quiescence, and more [

13]. The outputs include feedback that modifies the subsequent input state of the body and influences the immune system computer itself – antibodies, memory cells, reactivity thresholds, cell numbers, dynamics and more [

13]. Repetition of inputs can lead to the strengthening of network interactions or, conversely, to the weakening of computed outputs – immune tolerance [

14]. In principle we can conclude that immune computation is not linear - stronger input signals can lead both to stronger or weaker output responses depending on the context. We can also say that immune computations of body state are not discrete digital responses but are analogue responses influenced by context, past history, and other variable factors. Immune computation emerges from a learning process - NML.

Evolution Rules Immune Computation

The molecules, cells, and processes engaged in immune computation, like life generally, are the products of evolution; what works, works to survive and reproduce; that which does not so work is lost to entropy [

6].

The Human Immune System Learns Well

The human immune system must have evolved to its present composition of molecules, cells, and processes during the millions of years that human species existed as small bands of hunters and gatherers [

15]. The present conditions of human existence began only about ten thousand years ago with the agricultural revolution and animal husbandry leading to large urban concentrations of people, revolutions in foodstuffs, metabolism, occupations, contacts with animals, parasites and infectious agents, along with new microbiomes, new chemicals, pollutions of all kinds, extended life spans and aging, worldwide travel, wars, weapons, governments, science, medicine and all the rest. The time frames of these radical changes in human existence are too recent to have enabled a worldwide genetic evolution of the human species including the human immune system. What evolved in the distant past continues to work now; human populations that have been urbanized only in the recent past manifest no genetic immune insufficiency [

16]. We must conclude that the original human immune system has learned to accommodate to new worlds of interactions, and it continues to learn. I propose calling this learning natural machine learning (NML).

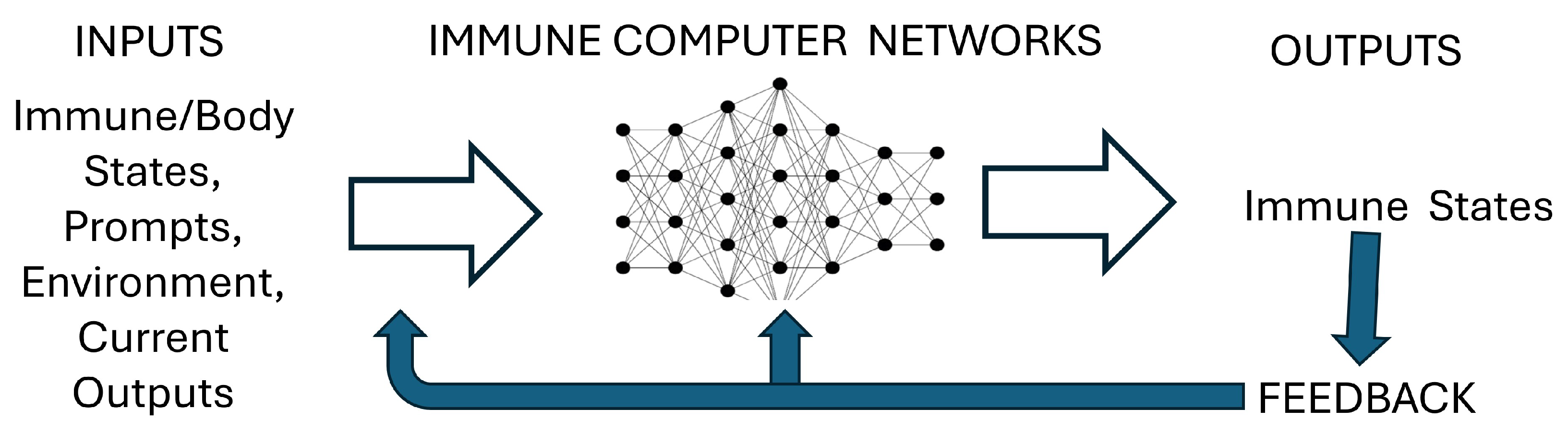

II. A Schematic Summary of Immune NML

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of immune network computation: the immune system computer is founded on Networks of interacting molecules and cells; the Inputs into the immune computer are the states of the body and of the immune system along with Prompts and Input from the environment; the Outputs of the computation are the resulting immune states. These Outputs feedback as new Input and modify immune/body Networks. The adaptive immune system learns to form networks of interactions and to generate diverse pathways of interactions through these networks. Below we shall discuss networks, phenotypes, self-immunity, prompts, training, feedback regulation, and training-based therapies.

Networks

Beyond individual lymphocyte receptor selections, immune operations involve networks of connections [

2]; life emerges from networks. Networks are formally described by their nodes and edges: the nodes are the connected entities, and the edges are the connections between them [

17]. Nodes, however, may themselves be formed by internal networks: Molecules are nodes emerging from networks of connected atoms; cells are nodes emerging from networks of connected molecules; organisms are nodes of internal networks of cells and molecules; species are connected networks of organisms; and ecosystems are connected networks of species and environments. The networks of the immune system connect by chemical ligands and receptors and by neural interactions between individuals: sight, smell, hearing, touch and memory. Immune cell collectives involve multiple innate and adaptive cell types (neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, and more) [

13]. Immune networks occupy many organs, including skin, lymph nodes, Payer’s patches, the spleen, the thymus, the bone marrow, the tonsils, among others, and immune cells migrate through lymph vessels, blood vessels, and extracellular space [

13]. The crowd wisdom of immune cells [

4], and the continuing entry of new stem cells generate very complex immune networks. All of life’s networks are nested; they interact simultaneously across multiple scales of time and space – cells within organisms within species within ecosystems. And all the while, these multi-scaled, nested operations continue to evolve [

6].

Phenotypes

A phenotype is the observable appearance and behavior of an organism that emerges from a combination of its expressed genes and its interactions, both internal and environmental [

12]. Phenotypes are critical to life because evolution tests the survival of phenotypes and not of isolated genes [

18]. Phenotypes are generated by networks and by pathways of networked interactions within the immune system and between the immune system and the body. NML training organizes immune/body networks and the various interaction pathways through them. We shall discuss NML training below in greater detail as we introduce self-immunity, prompts, and microbiomes.

Self-Immunity

Essential self-immunity, as distinct from autoimmunity, is required to protect and maintain the organism [

13]. The immune system was discovered by its ability to reject foreign and infectious agents that endanger the body [

19]. But we have learned that the immune system also interacts with the healthy individual: it supports healthy microbiomes; it removes aged and abnormal body cells; it rejects tumors; it heals wounds and injuries; it helps regulate growth and development; and it adjusts metabolism among other functions [

4]. These responsibilities require the immune system to interact with the body and to learn to respond to diverse body states [

3].

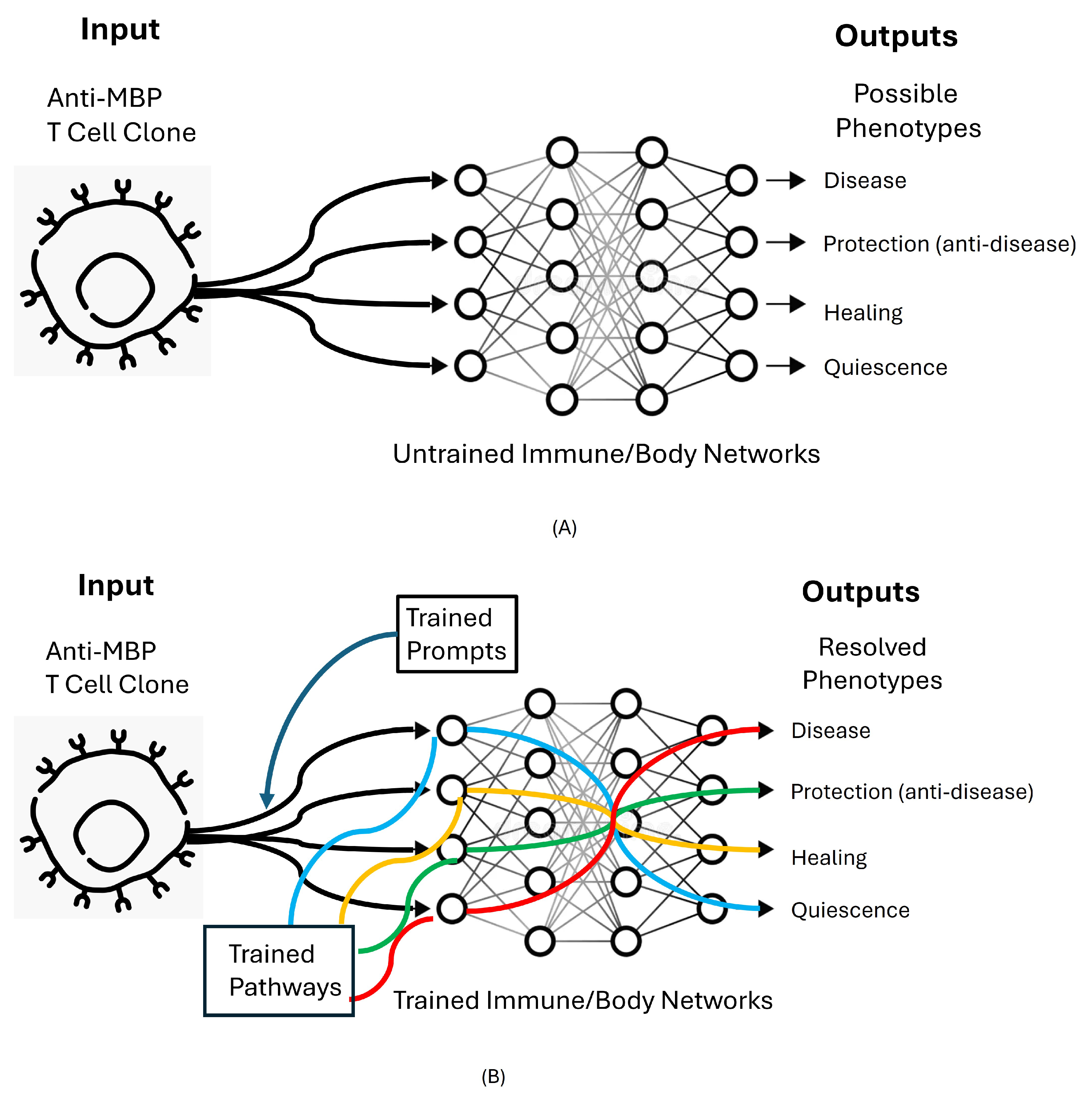

The close relationship between essential self-immunity and autoimmune disease is demonstrated by the ability of a single clone of T cells reactive to an epitope of myelin basic protein (MBP) to induce in rodents a paralytic autoimmune disease (EAE) [

20], or to induce resistance to EAE [

21]. The same T cells can also help mediate the healing of a nervous system injury [

22], inhibit nerve conduction [

23], or persist in the body with no overt effects [

24]. Thus, a single set of T cell interactions with a single self-antigen epitope can initiate different phenotypes; different interaction pathways can be triggered by the same initial T-cell receptor-MBP interaction; see

Figure 2A. The induction of disease and the resistance to disease mediated by single clones of T cells have been confirmed in autoimmune models of thyroiditis [

25], arthritis [

26], and type-one diabetes [

27]. Burnet’s concept of clonal selection does not explain self-immunity.

Prompts

Prompts in the context of immune NML designate molecular signals connecting immune system interactions with itself, with the body, and with infectious agents. In the context of AI, prompts designate computable information supplied by human interrogators to trigger a response from a computer machine-learning system [

28]. In the absence of a prompt, ChatGPT has nothing to say; the prompt directs the computation machinery to retrieve information relevant to the prompted task and to formulate a response [

29].

The body prompts the immune system differently in a dangerous infection and in a healthy carrier state, even to the same microbes [

30]. Prompts from the body such as Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) activate effector phenotypes [

31]. Infectious agents, too, prompt the immune system into effector modes by way of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) [

32]. PAMPs are recognized by immune cells using Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors [

33] and NOD-like receptors [

34]. The body, infectious agents, and the immune system are in constant, repetitive dialogue [

35]. Different states of the body can prompt the same anti-MBP T cells into different network pathways leading to markedly different immune phenotype outputs; the prompts and network pathways emerging from different body states pictured in

Figure 2B resolve the uncertainty among the possible phenotypes shown in

Figure 2A. Prompts serve to establish context [

36].

Microbiomes

The organization of microbiome immunity is critical because all multi-cellular creatures, from plants to people, are chimeras composed of inherited self-cells together with not-self microbes (microbiomes) including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and others [

11]. Microbiomes and infectious microbes are basic features of ecosystems; they are necessary elements in the evolution of multi-cellular organisms and their immune systems. Healthy microbiomes expressing foreign DNA populate us; their presence is required for healthy metabolism and for the development of body organs such as the gut [

37] and the immune system itself [

38], The brain is affected by the gut microbiome [

39]. Even tumors house characteristic microbiomes [

40]. A healthy person bears more microbiome DNA than she or he bears parental DNA [

41]. The cooperative arrangements between host organisms and their microbiome partners are understandable in the light of mutual evolution by survival of the fitted [

6].

The immune system, through training, learns to distinguish organisms of the healthy microbiome from pathogenic microbes, which may be very similar antigenically [

42]. Just as the immune system reacts differently in essential, physiological self-immunity and in autoimmune disease, the immune system reacts differently to healthy microbiomes and to pathogenic infections. Pathogenic and healthy microbes are distinguishable by the different prompts emitted by the host body tissues. Immune discrimination is not between “self” and “not-self” but between prompts indicating “healthy” or “unhealthy” tissue states and infections [

43]. To complicate the challenge, the same microbiome may be healthy in the gut and pathogenic in the brain or lung [

44]. The immune system must continuously learn and evaluate shifting situations.

III. Immune System Training in NML

NML training describes inputs that prepare the immune system to respond effectively to future challenges. Vaccination is an example of immune training: individuals vaccinated against measles have learned how to respond in the future to live measles virus, and, compared to the non-vaccinated, the vaccinated enjoy protection from disease caused by the virus [

45]. Like other forms of immune training, vaccination involves complex learning [

46]. In this section we shall discuss other training processes, some which are not usually defined as training.

Figure 2B shows that immune NML training organizes the Prompts and Pathways that enable discrete Input cells and molecules to follow different pathways through immune interaction networks to compute resolved Output phenotypes. This section focuses on training supplied by mother, by the immunological homunculus, by heat shock protein (HSP) molecules, and by the organs of immune training.

Mother

One’s natural mother is a valuable source of immune training [

2]: her ability to court, mate, become pregnant and give birth suggests that inheriting her immune system and her microbiomes enable healthy survival in the environment her baby will share with her. One may say that mother adds her individual immune experience to the training modalities learned by the species as a whole.

Before birth, mother provides immune system training by way of her IgG antibodies: mother’s placenta actively transports her IgG antibodies into the blood of the developing fetus; maternal antibodies of the IgM and IgA isotypes are not transmitted across the placenta [

47]. The IgG antibodies outfit the newborn with a repertoire of antibodies that has enabled mother to cope immunologically with the environment that awaits the emerging newborn.

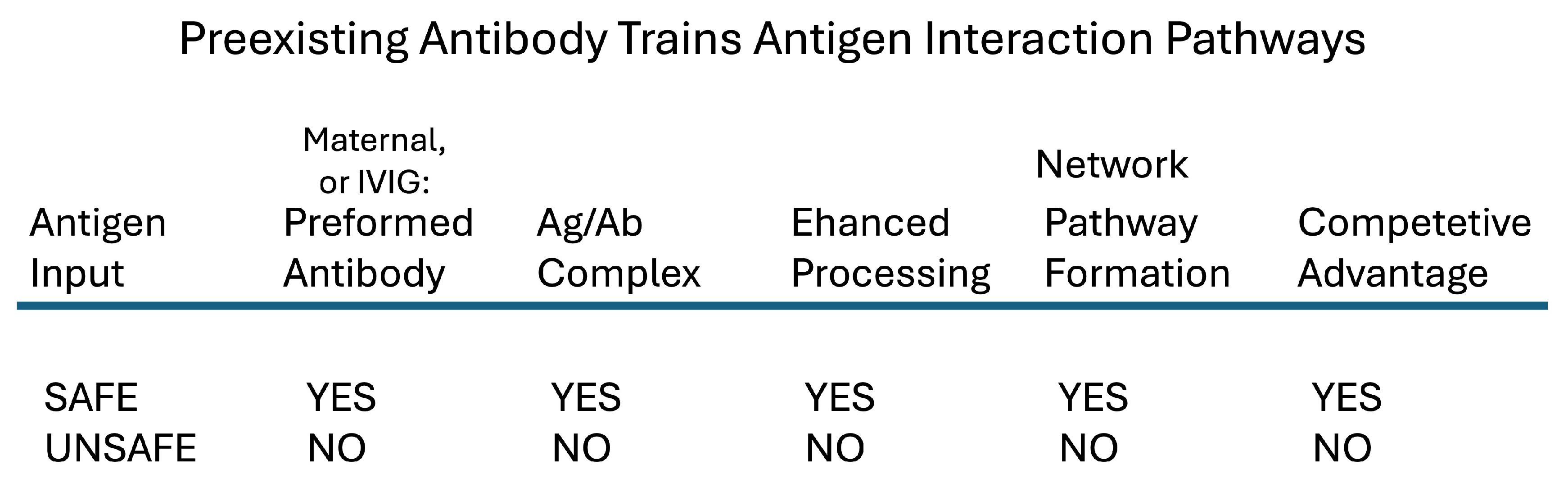

Maternal IgG also provides the immune system with a mechanism that generates a healthy antibody repertoire: newly encountered antigens that become complexed with preexisting maternal IgG antibodies are phagocyted and processed efficiently by the baby’s immune cells in network pathways not available to the same antigens not bound by transferred IgG [

48]. Antigens reacting with healthy maternal IgG antibodies enjoy a competitive advantage in priming newborn immune system network pathways compared to other, unanticipated antigens (See

Figure 3).

Mother’s influence on baby’s developing antibody network pathways persist as long as the maternal antibodies last, at least for the first half year of life [

49]. IVIg antibody therapy in adult life also provides effective therapeutic training – see below.

At birth, the newborn human exits mother’s vagina together with vaginal fluid and feces; these substances transmit mother’s vaginal and gut microbiomes to the newborn [

50]. Babies delivered by caesarian section exit surgically through mother’s skin and receive only her skin microbes; the deprivation of maternal gut microbiomes negatively affects the health of the newborn [

51]. Preliminary experiments have been done to outfit cesarian-born babies with mother’s microbiome by administering to the newborn maternal secretions at birth [

52].

After birth, maternal colostrum provides the nursing newborn with IgA secretory antibodies, T cells and T cell products, cytokines, hormones, and oligosacharides suited to the newborn’s microbiome along with other gifts [

53]. Continuing close maternal contact and care further enhance microbiome acquisition and newborn immune health [

54]. Mothers, and fathers too, continue immune system training by seeing that their children receive essential vaccinations from the healthcare system; measles vaccination for example [

45].

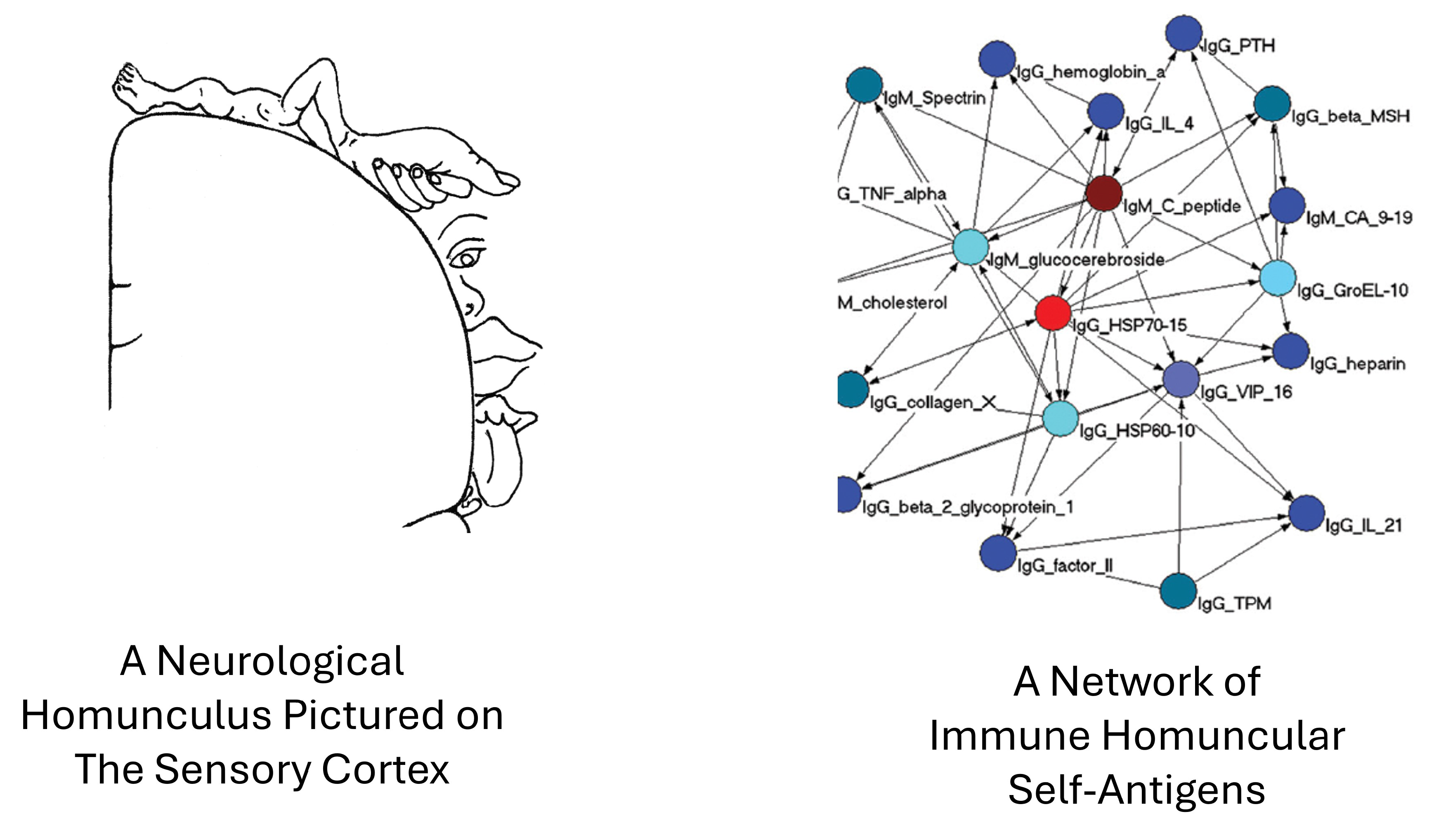

The Immunological Homunculus

Contrary to textbook teachings, the mature T-cell, B-cell, and antibody repertoires of healthy individuals contain lymphocytes and antibodies that react to self-antigens along with lymphocytes and antibodies that respond to foreign antigens [

10]. I introduced the term immunological homunculus (“little man”) to describe the self-antigens that naturally induce and interact with sets of self-reactive T cells, B cells, and antibodies. Previously, I have discussed the role of the immunological homunculus in filtering and focusing the immune response [

2]. Filtering and focusing are likely to contribute to NML training just as they contribute to AI machine learning [

36].

Responses to homuncular antigens are widely shared among members of the species: unrelated humans are born with self-made IgM and IgA autoantibodies to very similar sets of homuncular self-antigens [

55].

I borrowed the term homunculus from neurology where it designates areas of the nervous system that serve defined areas of the body [

56]. Species genes inherited from mother and father encode the expression of the homuncular self-antigens that positively select for homuncular T cells, B cells, and antibodies [

57]; the inherited expression of homuncular self-antigens reflects the immune experience of the species.

The prenatal and postnatal expression of the homuncular set links together these self-antigens and the resulting T cells, B cells, and self-antibodies in an integrated network of interaction pathways [

58]. The functions of these proposed network pathways (

Figure 3) need experimental analysis. It would be interesting to study the effects of vaccination with a foreign virus on the expression of homuncular self-antigens, T cells, B cells, and autoantibodies; are immune reactions induced by non-self infectious agents accompanied by modifications in the self-reactive immunological homunculus?

Antigen receptor binding sites appearing in different individuals are termed public receptors; we found that a public T cell receptor was associated with reactivity to the homuncular antigen HSP60 [

59]. Likewise, we can test whether other targets of public T cell receptors are homuncular self-antigens. Neurological and immunological homunculi are schematically pictured in

Figure 4.

Heat Shock Proteins

Among the prominent body molecules that activate homuncular T cells and B cells are heat shock proteins (HSPs). HSP molecules are central in networks of homuncular antigens [

60]; most other homuncular antigens are connected to them in dependency networks – see

Figure 4. HSPs are among the most conserved molecules in evolution: they are prevalent molecules in bacteria, and the sequences of human HSP molecules are not unlike bacterial HSP sequences that evolved more than a billion years earlier [

61]. HSP molecules function as chaperones essential in protein synthesis and protein folding during normal physiology and in reactions to stress [

62].

HSPs are both antigens and prompts. The presence of HSPs in the immunological homunculus guarantees that the immune system will continuously generate T cells and antibodies that recognize HSP molecules. The conservation of HSPs as chaperones in both humans and microbes ensures the cross-reactivity of anti-HSP immunity [

63]. In addition, the functions of HSPs in protein synthesis and in stress enable HSP molecules to function as prompts that reveal the healthy and stressed states of body cells and tissues [

64]. The outcomes of HSP-immune interactions are many; I cite only a few here.

Targets for anti-microbial immunity: the major microbial antigens targeted by mammalian immune systems include self-like HSP antigens [

63].

Targets for T cell regulation: the mammalian immune system contains regulatory T cells that recognize HSP60 target molecules expressed by activated T effector cells generally; T cell anti-HSP60 regulators down-regulate inflammatory responses involving activated effector T cells [

65].

Prompts that can quantitatively stimulate either pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune reactions: the activities of innate immune cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) and lymphocytes (T cells and B cells) are enhanced by high concentrations of HSP60 and suppressed by low concentrations of HSP60; a quantitative HSP60 network regulates immune responses [

66].

Autoimmunity: Administration of HSPs can activate or suppress experimental autoimmune diseases like arthritis [

67], lupus [

68], and type-1 diabetes [

69], depending on tissue and immune states.

The tumor microenvironment: Tumors express HSPs [

70]. We have found that bladder cancer that invades the muscular layer of the bladder is associated with HSP molecules in the urine [

71].

In short, HSP molecules, prominent members of the immunological homunculus, exert a wide range of effects on the body, on the immune system, and on microbial immunity. We do not know if other self-antigens of the immunological homunculus perform similar functions, but clearly its HSP members are important in immune system training and regulation.

IV. The Organs of Immune Training

The training environment includes factors that are external to the organism and factors that are internal to the organism. External factors are many and varied: infectious agents, allergens, diet, social contacts, medical care systems, climate, weather, and more. I shall only mention some important organs in the internal environment involved in immune system training.

T-Cell Training in the Thymus

The thymus was discovered to be involved in the differentiation of T-cells [

72]. Functional T cell repertoires require the selection of precursor stem T cells migrating from the bone marrow to the thymus. In the absence of a thymus in early life children manifest a high incidence of immune malfunction [

73]. The thymus is important in the development of public, shared T cell receptors [

59]. We can conclude that lymphocyte training in a healthy thymus is necessary for the development of a healthy immune system. Despite its importance, the thymus undergoes atrophy with aging; the reason is not known[

74], but it is conceivable that programmed thymic atrophy might serve to limit the NML process in the mature adult.

How the thymus works to prevent autoimmune disease is not known, but it cannot be by extensive deletion of self-reactive T cells, as was originally proposed [

8].

B-Cell Training

Training of the B-cell repertoire is thought to take place in the bone marrow [

75]. Like T cells, B cells and their antibodies were believed to be purged of high-affinity self-antigen recognition; but this belief is contradicted experimentally by the presence of the healthy homunculus.

Lymphocyte Feedback to the Thymus

Samples of mature T cells that have been activated by immune reactions in the body return to the thymus and persist there [

24]. The functions of thymus-returning T cells have yet to be determined, but such T cells could provide the training environment of the thymus with feedback expressing the performance of previously trained, mature T cells [

76]. T-cell feedback could influence the selective training of coming generations of T cells in presently unknown ways.

Ergotypic T-Cell Training

Injecting rodents with a sample of their own peripheral T cells induces resistance to EAE – provided that the T cells had been activated by specific antigens or general mitogens before injection [

77]. These ergotypic (activated) T cells modify the phenotype of the autoimmune response to MBP – the treated animals activate T cells that respond to the MBP self-antigen but now the phenotype of the response to MBP in vivo changes from disease to resistance to disease. Training using ergotypic T cells may be of therapeutic use, see below.

V. NML Feedback Regulation

The schematic illustration of immune NML in

Figure 1 shows that the Outputs from the immune computer return to the system as Feedback. Feedback modifies the Input and also affects the immune network computer. For example, an inflammatory response to a viral infection adds a new input to the immune computer and modifies network computation interactions by modifying metabolism, blood flow, tissue stress, HSP expression, cell proliferation and cell numbers, prompts, and other factors. Repeating Input affects the “strength” of ongoing interactions [

78]. The effects of Feedback on the contexts of input and immune computation ensure the non-linearity of immune NML; non-linearity is a mark of AI machine learning [

79]. In these ways, Feedback regulates the NML process. In contrast to NML Feedback, computer machine learning is optimized by quantitative measurements of loss functions and gradient descent or other measures programmed by humans [

80]. Feedback controls both NML and artificial machine learning, but in different ways.

VI. Training-Based Therapies

A common feature of many different autoimmune diseases, and even of some tumor microenvironments, is the misapplied expression of an otherwise normal inflammatory or healing response program [

81]. A damaging output phenotype emerges from an inappropriate immune system computation; the immune system wrongly concludes that otherwise healthy tissue needs fixing. Chronic inflammation is the outcome. Immune training organizes phenotypes; therefore, immune training agents are candidates for treating such immune diseases. Training modalities enable us to communicate with the immune system, as it were, in its own language. Three examples of training modalities used for therapy are IVIg, T-cell vaccinations, and HSP molecules.

Therapeutic IVIg

Intravenous infusion of IgG collected from healthy donors (IVIg) is successfully used to treat persons suffering from various autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), idiopathic thrombocytopenia (ITP), Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, polyneuropathies, multiple sclerosis, and Kawasaki disease [

80]. Various mechanisms of action for IVIg treatment have been suggested [

82] , but no single mechanism has been exclusively documented. We did an experiment in which we used IVIg to treat rodents suffering from induced EAE. We found that IVIg treatment prevented the disease; a heathy phenotype was maintained despite the induction of anti-MBP T cells that were virulent and caused EAE upon transfer into naïve recipients [

83]. This finding demonstrated that IVIg therapy induced a shift to a healthy phenotype despite the induction and continued presence of potentially virulent autoimmune T cells.

The concept of NML training suggests that therapeutic IVIg might mimic the training induced in the newborn by maternal IgG antibodies. Infusions of healthy IgG antibodies in adults as well as in developing babies can be viewed as suppressive competition with immune reactions to pathogenic antigens (

Figure 3); such competition could explain the decrease in the titers of pathogenic autoantibodies seen in treated patients [

84]. Training a healthy phenotype during immune system development foretells a healthy phenotype induced by IVIg treatment in adulthood.

These ideas need backing by experimental observations. Experiments can be done to test the effects of IVIg on the expression of homuncular antigens and homuncular autoantibodies in health and in autoimmune conditions; in the presence or absence of the thymus; and in the presence or absence of a healthy microbiome. .

T Cell Vaccinations

Ben-Nun, Wekerle and I discovered that lines and clones of autoimmune T cells reactive to MBP could mediate EAE upon intravenous injection [

21]; it then occurred to us that such T cells acting as the etiologic agents of an autoimmune disease might be used to “vaccinate” against the disease. Attenuated measles virus can vaccinate against measles, might an attenuated anti-MBP T clone be used to vaccinate against EAE? The answer was yes – both active and clone-mediated EAE could be resisted after T cell vaccination. The vaccinating T cells only had to have been activated by antigens or mitogens before vaccination; resting T cells were not effective vaccines [

21].

Subsequently, Lohse and colleagues discovered that activated T cells were able to vaccinate against autoimmune disease even if the T cells bore no specificity for the autoimmune target self-antigen – the T cells had to have been activated by a mitogen [

77]. We called these activated T cells ergotypic T cells from the Greek ergon, meaning activated. Hence, this treatment was termed ergotypic T cell vaccination. As we demonstrated previously [

24], activated T cells reentered the thymus – the organ of T cell training. Thus, we might consider the administration of activated T cells as a T cell training modality.

T cell vaccination was found to be safe and effective in treating multiple sclerosis patients [

85], including those who had failed respond to other treatments [

86]. Additional clinical trials are justified.

HSP Molecule Therapies

As mentioned above, HSP molecules have been found to be involved as targets, prompts, and regulators in many different immune and autoimmune interactions and clinical phenotypes. A peptide from HSP60 has been successful in a phase 2 trial treating humans with new onset type 1 diabetes [

87]. Peptides of HSP70 show promise in human arthritis [

88] The details of these and other studies are beyond the scope of this article, but the results suggest that experiments should be done to test the uses and mechanisms of HSPs in diverse immune, autoimmune, and neoplastic conditions.

VII. Conclusions

The results described here call attention to the network structure of immune phenotypes beyond the basic selection of clonal repertoires. Training is important in the development of immune NML (

Figure 1), and the elements that train the system can be used as therapeutic agents later in life to generate healthy phenotypes [

Figure 3]. Training elements like IVIg, T cell vaccination, and HSP molecules appear to be effective treatments and are free of most of the undesirable side effects of suppressive therapies that disable the immune system [

89]. Unfortunately, the Clonal Selection paradigm of immune regulation has left little room for considering antigen-non-specific therapeutic initiatives. The observation that BCG vaccination might help prevent Alzheimer’s Disease [

90] is a further example of immune therapy that is outside the realm of clonal selection.

Immune NML should stimulate new approaches to immune therapy. We don’t yet know how immune NML works in sufficient detail, but research combining immune NML with computer modeling could be revealing. Indeed, computer scientists and immunologists might be guided by NML to discover general principles of machine learning applicable to the organization of both the living and the not living.

References

- J Doyne Farmer, Norman H Packard, and Alan S Perelson. The immune system, adaptation, and machine learning. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1986, 22, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irun R Cohen. The cognitive paradigm and the immunological homunculus. Immunology today 1992, 13, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irun R Cohen. Real and artificial immune systems: computing the state of the body. Nature Reviews Immunology 2007, 7, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irun R Cohen and Sol Efroni. The immune system computes the state of the body: crowd wisdom, machine learning, and immune cell reference repertoires help manage inflammation. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiola Curion and Fabian J Theis. Machine learning integrative approaches to advance computational immunology. Genome Medicine 2024, 80, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Irun R Cohen and Assaf Marron. The evolution of universal adaptations of life is driven by universal properties of matter: energy, entropy, and interaction. F1000Research 2020, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan De Houwer, Dermot Barnes-Holmes, and Agnes Moors. What is learning? on the nature and merits of a functional definition of learning. Psychonomic bulletin & review 2013, 20, 631–642. [Google Scholar]

- Sir Frank Macfarlane, Burnet; et al. The clonal selection theory of acquired immunity, volume 3. Vanderbilt University Press Nashville, 1959.

- Alfred I Tauber. Immunity: the evolution of an idea. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Yifat Merbl, Merav Zucker-Toledano, Francisco J Quintana, Irun R Cohen, et al. Newborn humans manifest autoantibodies to defined self molecules detected by antigen microarray informatics. The Journal of clinical investigation 2007, 117, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugene Rosenberg and Ilana Zilber-Rosenberg. The hologenome concept of evolution after 10 years. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Holden T Maecker, J Philip McCoy, and Robert Nussenblatt. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the human immunology project. Nature Reviews Immunology 2012, 12, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irun R Cohen. Tending Adam’s Garden: evolving the cognitive immune self. Elsevier, 2000.

- Charles RM Hay and Donna M DiMichele. The principal results of the international immune tolerance study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2012, 119, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Frank W Marlowe. Hunter-gatherers and human evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues, News, and Reviews 2005, 14, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustapha Mbow, Sanne E de Jong, Lynn Meurs, Souleymane Mboup, Tandakha Ndiaye Dieye, Katja Polman, and Maria Yazdanbakhsh. Changes in immunological profile as a function of urbanization and lifestyle. Immunology 2014, 143, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Muers. Edges, nodes and networks. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell Lande. Natural selection and random genetic drift in phenotypic evolution. Evolution, pages 314–334, 1976.

- John Travis. On the origin of the immune system. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2009.

- Avraham Ben-Nun, Hartmut Wekerle, and Irun R Cohen. The rapid isolation of clonable antigen-specific t lymphocyte lines capable of mediating autoimmune encephalomyelitis. European journal of immunology 1981, 11, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham Ben-Nun, Hartmut Wekerle, and Irun R Cohen. Vaccination against autoimmune encephalomyelitis with t-lymphocite line cells reactive against myelin basic protein. Nature 1981, 292, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irun R Cohen and Michal Schwartz. Autoimmune maintenance and neuroprotection of the central nervous system. Journal of neuroimmunology, 100(1-2):111–114, 1999.

- Yosef Yarom, Yaakov Naparstek, Varda Lev-Ram, Joseph Holoshitz, Avraham Ben-Nun, and Irun R Cohen. Immunospecific inhibition of nerve conduction by t lymphocytes reactive to basic protein of myelin. Nature, 303(5914):246–247, 1983.

- Yaakov Naparstek, Joseph Holoshitz, Steven Eisenstein, Tamara Reshef, Sara Rappaport, Juan Chemke, Avraham Ben-Nun, and Irun R Cohen. Effector t lymphocyte line cells migrate to the thymus and persist there. Nature 1982, 300, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth Maron, RACHEL Zerubavel, AHARON Friedman, and Irun R Cohen. T lymphocyte line specific for thyroglobulin produces or vaccinates against autoimmune thyroiditis in mice. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 131(5):2316–2322, 1983.

- Joseph Holoshitz, Yaakov Naparstek, Avraham Ben-Nun, and Irun R Cohen. Lines of t lymphocytes induce or vaccinate against autoimmune arthritis. Science, 219(4580):56–58, 1983.

- Dana Elias, Yaron Tikochinski, Gad Frankel, and Irun R Cohen. Regulation of nod mouse autoimmune diabetes by t cells that recognize a tcr cdr3 peptide. International immunology, 11(6):957–966, 1999.

- Biao Zhang, Barry Haddow, and Alexandra Birch. Prompting large language model for machine translation: A case study. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 41092–41110. PMLR, 2023.

- Lin Guo. Using metacognitive prompts to enhance self-regulated learning and learning outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies in computer-based learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(3):811–832, 2022.

- Matthew P Williams and Roy E Pounder. Helicobacter pylori: from the benign to the malignant. The American journal of gastroenterology, 94(11):S11–S16, 1999.

- Ming Ma, Wei Jiang, and Rongbin Zhou. Damps and damp-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity, 57(4):752–771, 2024.

- Marco E Bianchi. Damps, pamps and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. Journal of Leucocyte Biology 2007, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shizuo Akira and Kiyoshi Takeda. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature reviews immunology 2004, 4, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace Chen, Michael H Shaw, Yun-Gi Kim, and Gabriel Nuñez. Nod-like receptors: role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2009, 4, 365–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv Frankenstein, Uri Alon, and Irun R Cohen. The immune-body cytokine network defines a social architecture of cell interactions. Biology direct, 1:1–15, 2006.

- Yair Neuman. AI for Understanding Context. Springer, 2024.

- Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, Filipa Godoy-Vitorino, Rob Knight, and Martin J Blaser. Role of the microbiome in human development. Gut, 68(6):1108–1114, 2019.

- Nita H Salzman. The role of the microbiome in immune cell development. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2014, 113, 593–598. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy R Sampson and Sarkis K Mazmanian. Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell host & microbe, 17(5):565–576, 2015.

- Gregory D Sepich-Poore, Laurence Zitvogel, Ravid Straussman, Jeff Hasty, Jennifer A Wargo, and Rob Knight. The microbiome and human cancer. Science, 371(6536):eabc4552, 2021.

- Eugene Rosenberg and Ilana Zilber-Rosenberg. Reconstitution and transmission of gut microbiomes and their genes between generations. Microorganisms, 10(1):70, 2021.

- Joseph M Pickard, Melody Y Zeng, Roberta Caruso, and Gabriel Núñez. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunological reviews 2017, 279, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido Kroemer, Léa Montégut, Oliver Kepp, and Laurence Zitvogel. The danger theory of immunity revisited. Nature Reviews Immunology 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtis F Budden, Shaan L Gellatly, David LA Wood, Matthew A Cooper, Mark Morrison, Philip Hugenholtz, and Philip M Hansbro. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut–lung axis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15(1):55–63, 2017.

- H Cody Meissner, Peter M Strebel, and Walter A Orenstein. Measles vaccines and the potential for worldwide eradication of measles. Pediatrics, 114(4):1065–1069, 2004.

- Susanne Rauch, Edith Jasny, Kim E Schmidt, and Benjamin Petsch. New vaccine technologies to combat outbreak situations. Frontiers in immunology, 9:1963, 2018.

- Patricia Palmeira, Camila Quinello, Ana Lúcia Silveira-Lessa, Cláudia Augusta Zago, and Magda Carneiro-Sampaio. Igg placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Journal of Immunology Research, 2012(1):985646, 2012.

- Eddy Roosnek and Antonio Lanzavecchia. Efficient and selective presentation of antigen-antibody complexes by rheumatoid factor b cells. The Journal of experimental medicine, 173(2):487–489, 1991.

- Genevieve G Fouda, David R Martinez, Geeta K Swamy, and Sallie R Permar. The impact of igg transplacental transfer on early life immunity. Immunohorizons, 2(1):14–25, 2018.

- Emma Ronde, Maaike Alkema, Thomas Dierikx, Sam Schoenmakers, Clara Belzer, and Tim de Meij. The influence of maternal gut and vaginal microbiota on gastrointestinal colonization of neonates born vaginally and per caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 25(1):1–10, 2025.

- Stephanie B Orchanian, Elaine Y Hsiao, et al. The microbiome as a modulator of neurological health across the maternal-offspring interface. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 135(4), 2025.

- Noora Carpén, Petter Brodin, Willem M de Vos, Anne Salonen, Kaija-Leena Kolho, Sture Andersson, and Otto Helve. Transplantation of maternal intestinal flora to the newborn after elective cesarean section (secflor): study protocol for a double blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC pediatrics, 22(1):565, 2022.

- Yong Joo Kim. Immunomodulatory effects of human colostrum and milk. Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, 24(4):337, 2021.

- Noel T Mueller, Elizabeth Bakacs, Joan Combellick, Zoya Grigoryan, and Maria G Dominguez-Bello. The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends in molecular medicine, 21(2):109–117, 2015.

- Asaf Madi, Sharron Bransburg-Zabary, Dror Y Kenett, Eshel Ben-Jacob, and Irun R Cohen. The natural autoantibody repertoire in newborns and adults: a current overview. Naturally Occurring Antibodies (NAbs 2012, 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Franck-Emmanuel Roux, Imène Djidjeli, and Jean-Baptiste Durand. Functional architecture of the somatosensory homunculus detected by electrostimulation. The Journal of physiology, 596(5):941–956, 2018.

- Constantin Fesel and Antonio Coutinho. Dynamics of serum igm autoreactive repertoires following immunization: strain specificity, inheritance and association with autoimmune disease susceptibility. European journal of immunology, 28(11):3616–3629, 1998.

- Alexander Poletaev and Leeza Osipenko. General network of natural autoantibodies as immunological homunculus (immunculus). Autoimmunity Reviews, 2(5):264–271, 2003.

- Asaf Madi, Asaf Poran, Eric Shifrut, Shlomit Reich-Zeliger, Erez Greenstein, Irena Zaretsky, Tomer Arnon, Francois Van Laethem, Alfred Singer, Jinghua Lu, et al. T cell receptor repertoires of mice and humans are clustered in similarity networks around conserved public cdr3 sequences. Elife, 6:e22057, 2017.

- MARTIN E Munk, BERND Schoel, SUSANNE Modrow, ROBERT W Karr, RA Young, and SH Kaufmann. T lymphocytes from healthy individuals with specificity to self-epitopes shared by the mycobacterial and human 65-kilodalton heat shock protein. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 143(9):2844–2849, 1989.

- Ulrich Zügel and Stefan HE Kaufmann. Role of heat shock proteins in protection from and pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 1999, 39, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Martin E Feder and Gretchen E Hofmann. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annual review of physiology, 61(1):243–282, 1999.

- Irun R Cohen and Douglas B Young. Autoimmunity, microbial immunity and the immunological homunculus. Immunology today, 12(4):105–110, 1991.

- Xolani Henry Makhoba. Two sides of the same coin: heat shock proteins as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for some complex diseases. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 12:1491227, 2025.

- Francisco J Quintana, Avishai Mimran, Pnina Carmi, Felix Mor, and Irun R Cohen. Hsp60 as a target of anti-ergotypic regulatory t cells. PLoS One 2008, 3, e4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco J Quintana and Irun R Cohen. The hsp60 immune system network. Trends in immunology, 32(2):89–95, 2011.

- Jagoda Mantej, Kinga Polasik, Ewa Piotrowska, and Stefan Tukaj. Autoantibodies to heat shock proteins 60, 70, and 90 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Stress and Chaperones 2019, 24, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aijing Liu, Concetta Ferretti, Fu-Dong Shi, Irun R Cohen, Francisco J Quintana, and Antonio La Cava. Dna vaccination with hsp70 protects against systemic lupus erythematosus in (nzb× nzw) f1 mice. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 72(6):997–1002, 2020.

- Ohad S Birk, Dana Elias, Alona S Weiss, Ada Rosen, Ruurd Van-Der Zee, Michael D Walker, and Irun R Cohen. Nod mouse diabetes: the ubiquitous mouse hsp60 is a β-cell target antigen of autoimmune t cells. Journal of Autoimmunity, 9(2):159–166, 1996.

- Marina Ferrarini, Silvia Heltai, M Raffaella Zocchi, and Claudio Rugarli. Unusual expression and localization of heat-shock proteins in human tumor cells. International Journal of Cancer, 51(4):613–619, 1992.

- David Margel, Meirav Pesvner-Fischer, Jack Baniel, Ofer Yossepowitch, and Irun R Cohen. Stress proteins and cytokines are urinary biomarkers for diagnosis and staging of bladder cancer. European urology 2011, 59, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques FAP Miller. The function of the thymus and its impact on modern medicine. Science 2020, 369, eaba2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara Vasconcelos Cavalcanti, Patricia Palmeira, Marcelo Biscegli Jatene, Mayra de Barros Dorna, and Magda Carneiro-Sampaio. Early thymectomy is associated with long-term impairment of the immune system: a systematic review. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 774780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis D Taub and Dan L Longo. Insights into thymic aging and regeneration. Immunological reviews 2005, 205, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard R Hardy and Kyoko Hayakawa. B cell development pathways. Annual review of immunology, 19(1):595–621, 2001.

- David B Agus, Charles D Surh, and Jonathan Sprent. Reentry of t cells to the adult thymus is restricted to activated t cells. The Journal of experimental medicine, 173(5):1039–1046, 1991.

- Ansgar W Lohse, Felix Mor, Nathan Karin, and Irun R Cohen. Control of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by t cells responding to activated t cells. Science 1989, 244, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrizia Scapini and Marco A Cassatella. Social networking of human neutrophils within the immune system. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 124(5):710–719, 2014.

- Sheng Chen, Stephen A Billings, and PM Grant. Non-linear system identification using neural networks. International journal of control, 51(6):1191–1214, 1990.

- Katarzyna Janocha and Wojciech Marian Czarnecki. On loss functions for deep neural networks in classification. arXiv preprint , 2017. arXiv:1702.05659, 2017.

- David Furman, Judith Campisi, Eric Verdin, Pedro Carrera-Bastos, Sasha Targ, Claudio Franceschi, Luigi Ferrucci, Derek W Gilroy, Alessio Fasano, Gary W Miller, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature medicine, 25(12):1822–1832, 2019.

- Claire Larroche, Youri Chanseaud, Paloma Garcia de la Pena-Lefebvre, and Luc Mouthon. Mechanisms of intravenous immunoglobulin action in the treatment of autoimmune disorders. BioDrugs, 16:47–55, 2002.

- A Achiron, R Gilad, Raanan Margalit, U Gabbay, I Sarova-Pinhas, Irun R Cohen, E Melamed, O Lider, S Noy, and I Ziv. Intravenous gammaglobulin treatment in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: delineation of usage and mode of action. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 57(Suppl):57–61, 1994.

- Marinos C Dalakas. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune neuromuscular diseases. Jama, 291(19):2367–2375, 2004.

- Dimitrios Karussis, Hagai Shor, Julia Yachnin, Naama Lanxner, Merav Amiel, Keren Baruch, Yael Keren-Zur, Ofra Haviv, Massimo Filippi, Panayiota Petrou, et al. T cell vaccination benefits relapsing progressive multiple sclerosis patients: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. PloS one, 7(12):e50478, 2012.

- A Achiron, G Lavie, I Kishner, Y Stern, I Sarova-Pinhas, T Ben-Aharon, Yoram Barak, H Raz, M Lavie, T Barliya, et al. T cell vaccination in multiple sclerosis relapsing–remitting nonresponders patients. Clinical immunology 2004, 113, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itamar Raz, Dana Elias, Ann Avron, Merana Tamir, Muriel Metzger, and Irun R Cohen. β-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes and immunomodulation with a heat-shock protein peptide (diapep277): a randomised, double-blind, phase ii trial. The Lancet, 358(9295):1749–1753, 2001.

- Julia Spierings and Willem van Eden. Heat shock proteins and their immunomodulatory role in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology, 56(2):198–208, 2017.

- Michael D Rosenblum, Iris K Gratz, Jonathan S Paw, and Abul K Abbas. Treating human autoimmunity: current practice and future prospects. Science translational medicine, 4(125):125sr1–125sr1, 2012.

- Ofer N Gofrit, Benjamin Y Klein, Irun R Cohen, Tamir Ben-Hur, Charles L Greenblatt, and Hervé Bercovier. Bacillus calmette-guérin (bcg) therapy lowers the incidence of alzheimer’s disease in bladder cancer patients. PLoS One, 14(11):e0224433, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).