1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of mortality worldwide, with coronary artery disease (CAD) accounting for a significant proportion of morbidity and healthcare burden [

1]. Atherosclerosis, the primary pathological mechanism underlying CAD, is now recognized as a chronic inflammatory process [

2,

3]. The inflammatory process not only contributes to plaque formation but also destabilizes existing plaques, leading to acute coronary events [

4,

5]. It has been established that immune system and inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets play an essential role in the occurrence of coronary atherosclerosis [

6,

7].

In addition to inflammation, nutritional status has been increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in atherosclerosis progression. Low serum albumin levels have been associated with increased inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and worse cardiovascular outcomes [

8,

9]. The relationship between inflammation, nutritional status, and CAD progression highlights the importance of discovering novel biomarkers.

The Naples Prognostic Score (NPS) has emerged as a novel composite biomarker integrating systemic inflammation and nutritional status. It incorporates serum albumin levels, total cholesterol (TC), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) to provide a comprehensive assessment of patient prognosis. NPS was first described in colorectal cancer by Galizia et al. It has subsequently been extensively studied in oncology [

10,

11,

12]. However, recent evidence suggests that it may also be useful in cardiovascular diseases [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Similarly, the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), initially developed for use in oncology, is a novel biomarker that integrates platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts, reflecting both systemic inflammation and immune response. SII has shown promise in predicting clinical outcomes in various cardiovascular conditions, including acute coronary syndromes and chronic heart failure [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Elevated SII levels have been associated with increased disease severity and worse clinical outcomes in CAD patients, suggesting its potential role as a simple yet effective risk stratification tool.

Angina pectoris, precipitated by ischemia, is the most prevalent manifestation of atherosclerotic CAD. The main diagnostic technique used to identify CAD in patients with stable angina pectoris (SAP) is non-invasive imaging scans. In light of recent guidelines, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) is a widely used noninvasive imaging technique that allows the assessment of myocardial ischemia and perfusion defects, guides clinical decision making in patients with suspected or known CAD [

23,

24]. MPS using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is a popular diagnostic method for identifying myocardial functional ischemia in patients with suspected CAD.

The correlation of inflammatory and nutritional markers with functional ischemia, documented by MPS, remains an area requiring further investigation. Given their well-established correlation with CAD, identifying accessible and cost-effective biomarkers associated with functional ischemia on MPS could significantly improve risk stratification. The present study aims to evaluate the predictive value of SII and NPS in identifying myocardial ischemia in in patients with SAP, thereby providing insight into their potential role in integrating inflammatory and nutritional markers with functional imaging in CAD assessment and diagnosis.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

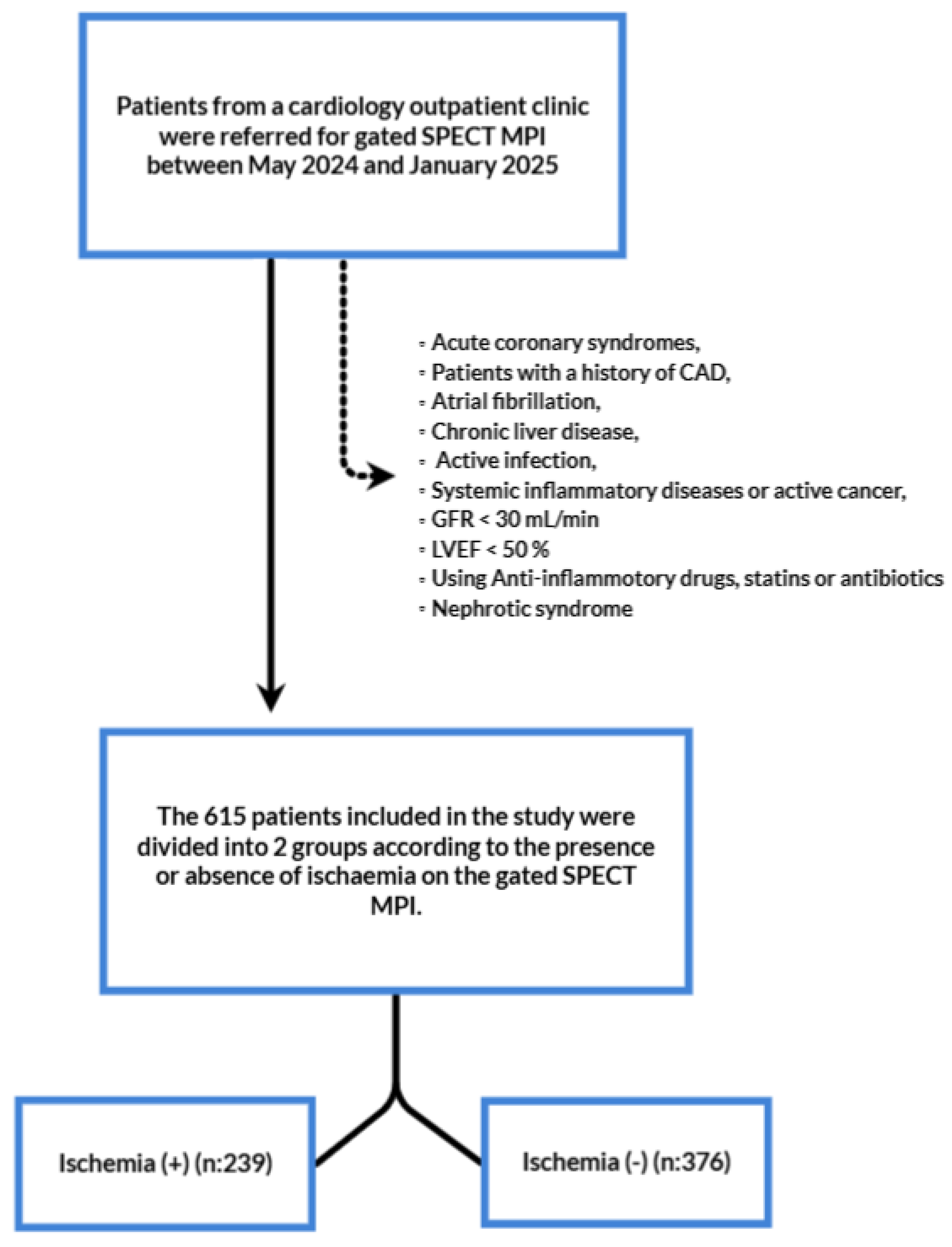

This is a single centered, retrospective study of patients diagnosed with stable angina pectoris. A total of 1186 patients who were diagnosed with SAP and underwent myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) according to the established guidelines at Karaman Training and Research Hospital between May 2024 and January 2025 were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria were defined as followings; patients over 18 years of age and who had undergone MPI with diagnosis of SAP. Patients were categorized into two group as no ischemia and ischemia. We used the traditional clinical classification of SAP that met the following criteria: Constricting discomfort in the front of the chest or in the neck, jaw, shoulder, or arm, precipitated by physical exertion, relieved by rest or nitrates within five minutes, and the continuation of these symptoms for more than two months. According to the same guidelines MPI was performed to those who had a moderate to high (15%-85%) clinical likelihood of obstructive CAD [

25]. Exclusion criteria were defined as followings; Acute coronary syndromes, patients with a history of CAD (including percutaneous or surgical revascularization), diseases that can affect serum albumin, total lymphocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil count, and TC levels including metabolic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome, severe renal impairment (defined as a creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/L and/or the need for renal replacement therapy), chronic liver disease, active infection, systemic inflammatory diseases and active malignancy, current or previous use of lipid lowering medications, current use of anti-inflammatory drugs, and patients with insufficient data for calculation of NAPLES score and SII. Following the application of exclusion criteria, a total of 615 patients were examined.

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study.

Our study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethical committee of the Karamanoglu Mehmetbey University, Karaman, Turkey. Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our study.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Information on demographic characteristics, previously diagnosed diseases like hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia (HL), chronic kidney disease, history of smoking and previous medications was obtained from medical records. DM was defined as a fasting glucose >126 mg/dL, HbA1c >6.5%, or history of antidiabetic medications. HT was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or a history of antihypertension treatment at enrollment. HL was defined as a total cholesterol level >240 mg/dL.

2.3. Laboratory Measurements

Blood samples taken from the patients on the day of their outpatient clinic admission were recorded from the database. Routine blood tests included; complete blood count, serum biochemical tests (renal and liver functions, C reactive protein (CRP, mg/dL), high density lipoprotein (HDL, mg/dL), low density lipoprotein (LDL, mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL) and TC (mg/dL). An automated hematology analyser (Mindray BC-6000) was used to measure hematological indices. In addition, creatinine, serum electrolytes, serum cholesterol levels and detailed liver function tests were measured with Beckman Coulter AU5800 modular analyser.

We divide the total neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count, and the total lymphocyte count by the monocyte count to calculate NLR and LMR respectively. The NPS was calculated using four components: NLR, LMR, TC level, and serum albumin level. Each of these parameters is assigned a score of either 0 (NLR ≤ 2,96, LMR > 4,44, TC > 180 mg/dL, serum albumin ≥ 4 mg/dL) or 1 (NLR > 2,96, LMR ≤ 4,44, TC ≤ 180 mg/dL serum albumin < 4 mg/dL) and the scores are summed. Patients were then evaluated as low NPS group (0-1-2) and high NPS group (3-4) according to NPS score. The SII index was calculated using the following formula from the blood count: platelet count × NLR.

2.4. Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

All patients underwent myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) using a standardized two-day stress/rest protocol with Technetium-99m methoxy isobutyl isonitrile (Tc-99m MIBI). Patients were instructed to fast for a minimum of six hours prior to imaging and to avoid caffeine-containing products for a period of 24 hours before pharmacologic stress testing.

The stress protocol involved treadmill exercise using the modified Bruce protocol. At the point of peak exercise (target heart rate = [220 – age] × 0.85), 20 mCi of Tc-99m MIBI was administered intravenously, after which exercise continued for a further minute. For patients unable to exercise, adenosine was infused intravenously at a rate of 140 µg/kg/min for six minutes, with 20 mCi of Tc-99m MIBI injected at the third minute (peak hyperemia).

Stress imaging was initiated 30–45 minutes following injection. Patients exhibiting perfusion defects on stress imaging underwent rest imaging with an additional 20 mCi of Tc-99m MIBI, acquired 30–45 minutes later. SPECT images were obtained using a dual-head gamma camera (Siemens Symbia, Germany) with SMARTZOOM™ collimators over a 180° arc (45° right anterior oblique to 45° left posterior oblique), using a 64 × 64 matrix, 3° intervals, and 60 projections per head. The analysis of perfusion defects was conducted semi-quantitatively using the Total Stress Score (TSS), Total Rest Score (TRS), and Total Difference Score (TDS), with the grading of ischemia as normal (TSS < 4), mild (TSS 4–8), moderate (TSS 9–13), or severe (TSS > 13). Two experienced nuclear medicine physicians independently reviewed the images, with any discrepancies resolved by consensus.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, US). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to investigate whether the normal distribution assumption was met. Categorical data were expressed as numbers (n) and percentage (%) while quantitative data were given as mean ± SD and median (25th – 75th) percentiles. While the mean differences between the groups were compared using the Student’s t test, the Mann Whitney U test was used to compare data that did not show a normal distribution. Qualitative data were analyzed by Pearson’s χ2 test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to determine potential cut-off values for NLR, LMR and SII as predictors of ischemia development. Where the area under the curve (AUC) was statistically significant, the optimal cut-off point was identified using Youden’s index. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy were also calculated. To identify independent predictors of ischemia, multiple logistic regression models were constructed. Any variable with a p < 0.15 in univariate analysis was considered for inclusion in the multivariate model. For each independent variable, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and Wald statistics were reported. A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

The study included a total of 615 patients divided into two groups; No ischemia (n=376) and Ischemia (n=239). Baseline characteristics were demonstrated in

Table 1. The mean age was 61.6±9.5 and 366 (59.5%) were man. Compared to the non-ischemic group, the ischemic group had a statistically significant lower proportion of women and a higher proportion of men (p<0.001). Body mass index (BMI), comorbidities like HT, DM, HL and smoking history were statistically similar between two groups (p>0.05).

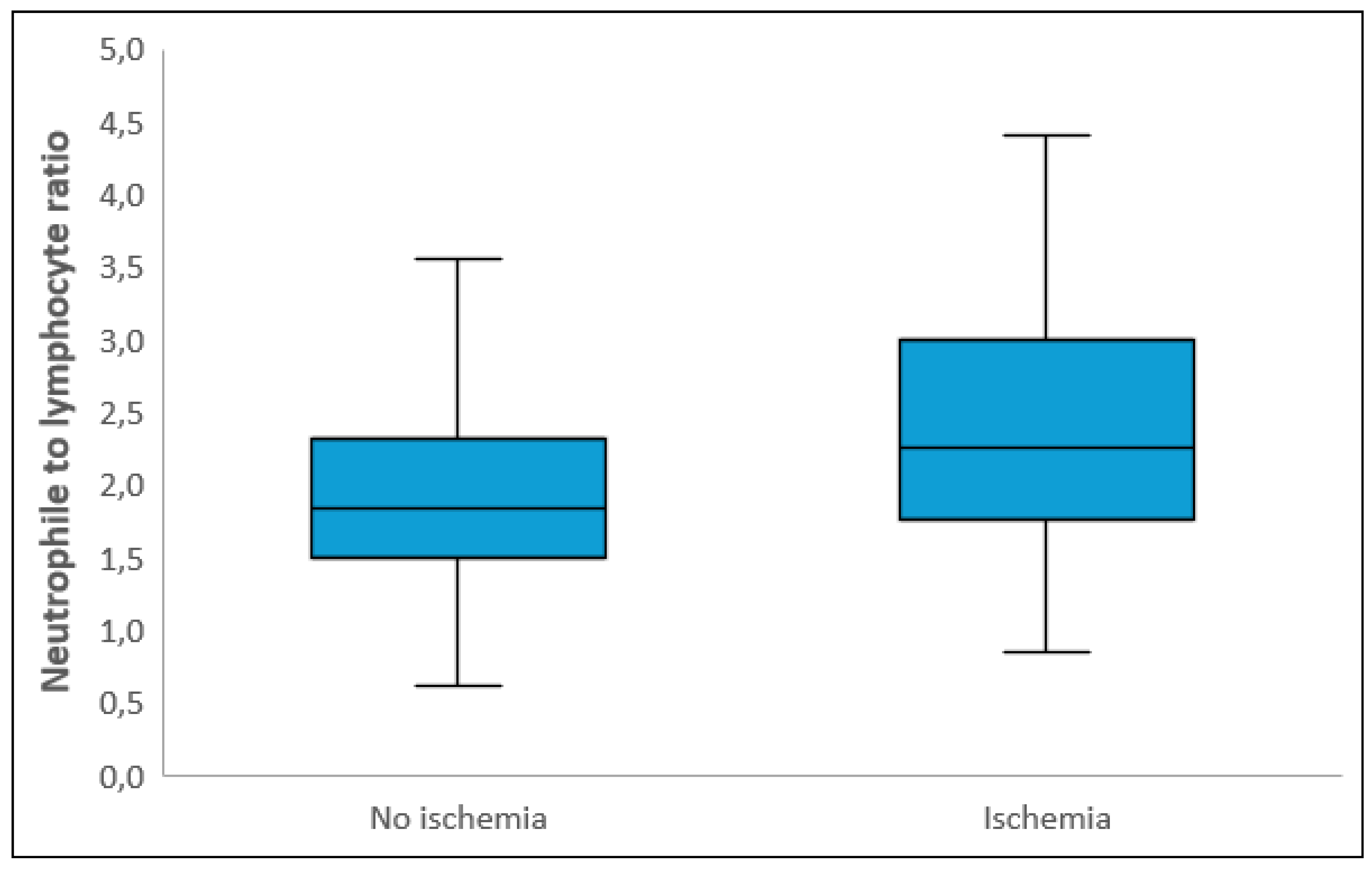

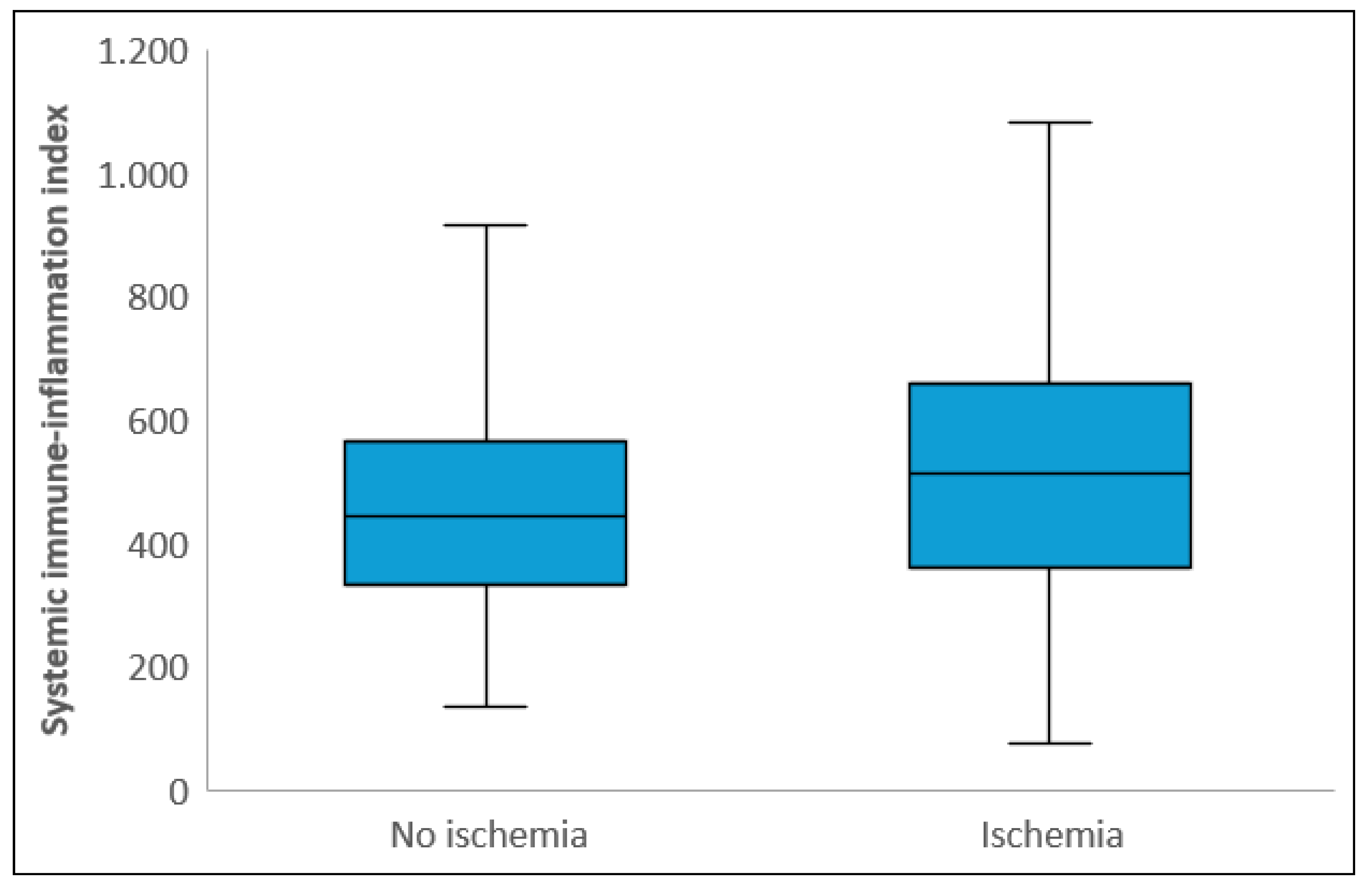

Laboratory parameters showed that white blood cell count, neutrophil count, CRP, and total cholesterol levels were significantly higher in the ischemic group, while albumin and PLT levels were significantly lower compared to the non-ischemic group (p<0.05). NLR and SII levels were also significantly higher in the ischemic group (p<0.001) (

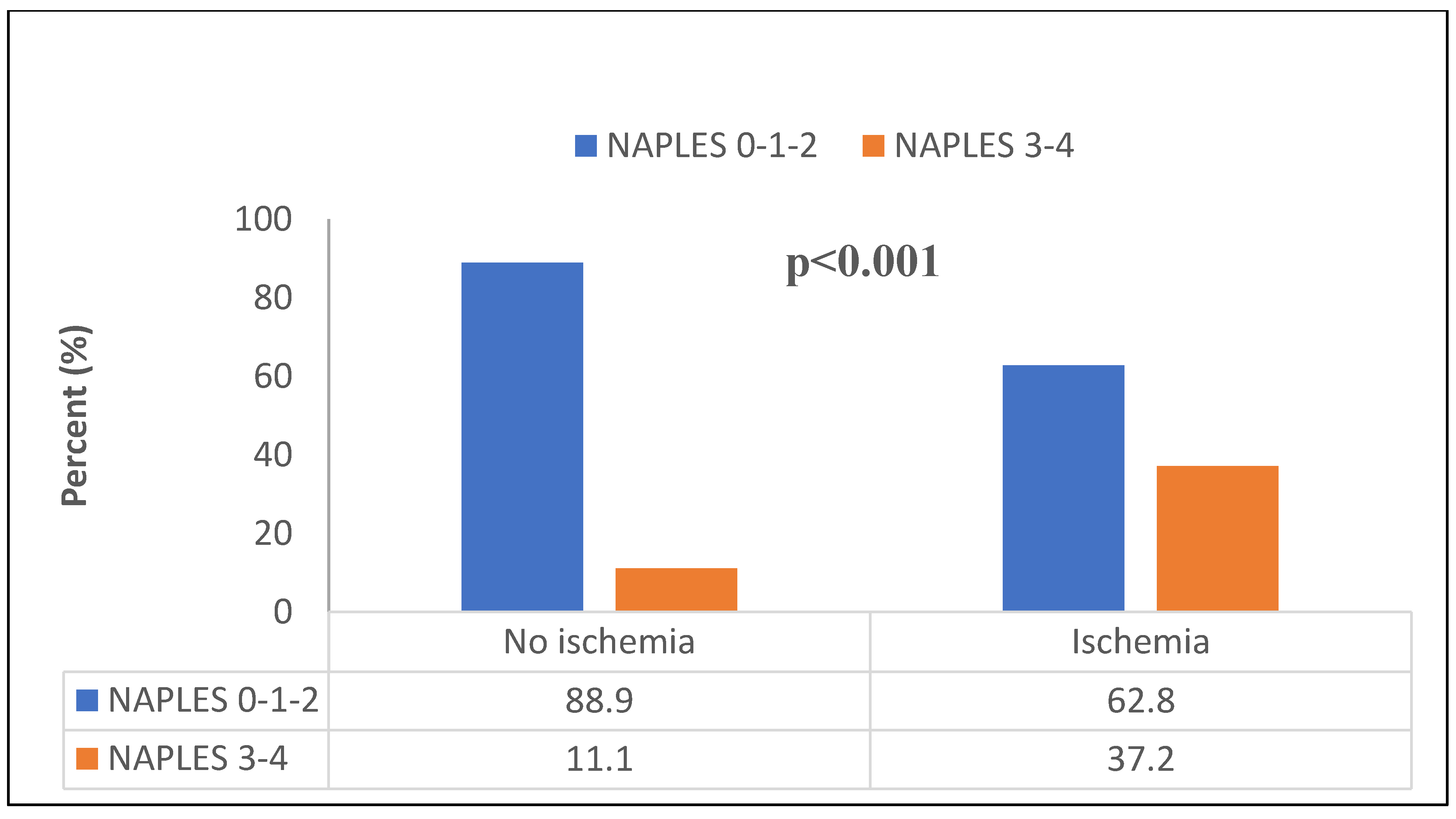

Figure 2 and 3). The median NPS was 1 (0 – 2) in the non-ischemic group and 2 (2 – 3) in the ischemic group (p<0.001). The distribution of those with low and high NPS in ischemic and non-ischemic groups was shown in

Figure 4. While 334 (88.9%) of the patients in the non-ischemic group had low NPS, 89 (37.2%) of the patients in the ischemic group had high NPS (p<0.001).

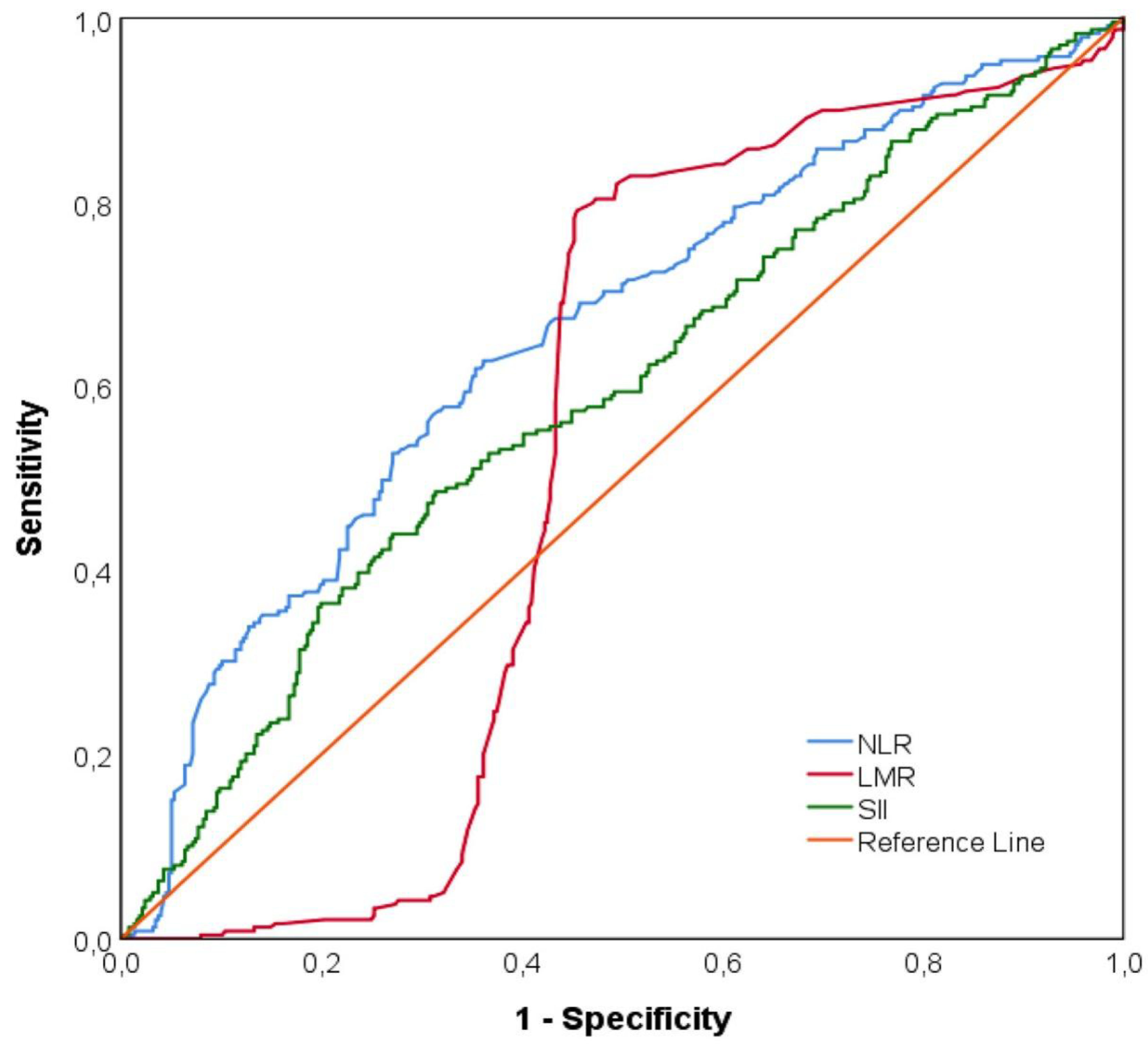

Figure 5 indicated ROC curves of NLR, LMR and SII levels to predict ischemia. NLR levels above 2.04 predicted ischemia with a sensitivity of 62.8% and specificity of 63.8% (AUC= 0.656 [95% CI: 0.611-0.700], p<0.001). SII levels above 528.27 predicted ischemia with area under the ROC curve = 0.588 [95% CI: 0.542-0.634] (p<0.001). The area under the ROC curve of LMR measurements was statistically insignificant in distinguishing the two groups (AUC=0.534, [95% CI: 0.487-0.581], p=0.159) (Supplementary Material 1).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that high NPS (OR= 4.427 [2.642-7.923], 95% CI; p<0.001), male sex (OR= 6.792 [4.168-11.068], 95% CI; p=0.004), higher CRP levels (OR= 1.181 [1.046-1.333], 95% CI; p=0.007), and NLR above 2.04 (OR= 1.580 [1.028-2.429], 95% CI; P<0.037) were independent predictors of ischemia (

Table 2). Due to multicollinearity between NLR and SII, these variables were not included simultaneously in the regression model. In Model 2, SII was incorporated into the analysis instead of NLR, which was excluded from this model to avoid redundancy with the first model. After multivariate adjustment, high NPS (OR= 4.945 [2.913-8.767], 95% CI; p<0.001), male sex (OR= 7.250 [4.430-11.865], 95% CI; p<0.001), higher CRP levels (OR= 1.191 [1.053-1.348], 95% CI; p=0.005), and SII above 528.27 (OR= 1.676 [1.072-2.621], 95% CI; P<0.023) were independent predictors of ischemia (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

To the best our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the utility of the NPS and SII as predictors of functional myocardial ischemia detected by MPS. Our findings demonstrate that NPS, a composite score reflecting both inflammatory and nutritional status, serves as a robust independent predictor of ischemia, with high NPS (scores 3–4) associated with a 4.4- to 4.9-fold increased likelihood of ischemia. Male sex, higher CRP, NLR, and SII also emerged as significant predictors, reinforcing the interplay between systemic inflammation and ischemic burden in stable CAD. The findings highlight several key aspects regarding the interplay between inflammation, nutritional status, and the risk of myocardial ischemia.

Atherosclerosis is a common disease with significant clinical consequences, including CAD. Identifying myocardial ischemia in patients with SAP remains crucial for optimal clinical management and prognosis. Early recognition of ischemia allows for timely initiation of medical therapy, risk factor modification, and when necessary, revascularization procedures. Patients with CAD typically develop myocardial ischemia. The genesis of atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia is complex and involves several biological mechanisms, including biomolecular and inflammatory processes [

26,

27]. During the early phases of myocardial ischemia, inflammatory responses occur in myocardial tissue. CRP, albumin, and NLR have been proposed as potential biomarkers for inflammation, particularly in the context of acute coronary syndromes [

28,

29]. Numerous studies have identified NLR as a significant predictor of acute and stable CAD [

4,

30,

31,

32]. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of the CRP/albumin ratio (CAR) as a sensitive and accessible inflammatory index in cardiovascular disease. In two separate studies, elevated CAR was found to be an independent predictor of both the severity of myocardial ischemia on MPS and the extent of CAD evaluated by angiography [

33,

34]. To investigate the relationship between myocardial perfusion and NLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, platelet distribution width and RDW, Ozdemir et al [

35] studied 262 patients with abnormal and normal MPS. Those diagnosed with myocardial ischemia or infarction had significantly higher neutrophil counts and NLR. Similarly, in our study, CRP, WBC, neutrophils and NLR among inflammatory markers were higher in the ischemia group.

In a recent study where NPS was only assessed in 110 patients with MPS and 37 patients in the ischemic group, albumin and NPS were found to be predictors [

36]. Our univariate analyses showed that low levels of albumin were associated with the presence of ischemia in MPS, as has been found in similar studies evaluating CAR and NPS. [

34,

36,

37]. This is consistent with the literature suggesting hypoalbuminemia reflects a chronic inflammatory state and malnutrition, both of which are known to contribute to atherogenesis and myocardial vulnerability [

8,

38]. However, albumin alone did not retain significance in multivariable models, which underscores the added prognostic value of integrated scores like NPS over individual laboratory parameters. These findings reinforce the pathophysiological link between systemic inflammation, nutritional depletion, and ischemic burden. Our results extend this perspective by demonstrating that the NPS—which integrates albumin, total cholesterol, NLR, and LMR—provides an even stronger association with ischemia. This supports the hypothesis that composite biomarkers better capture the multifactorial nature of CAD progression than individual laboratory parameters.

This is the first study to investigate SII index for myocardial functional ischemia on MPS in stable anjina patients. The statistically significant relationship between the higher SII index and myocardial ischemia was another notable finding of our analysis. The SII integrates platelet count with NLR (NLR x platelet count), suggesting a complex interaction between the immune response and hemostatic balance in the setting of CAD. The high SII levels have been shown to be significantly associated with poorer clinical outcomes in several studies of cardiovascular disease and have proven useful as a simple risk stratification tool in clinical practice [

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

39]. It has been discovered that platelets contribute to the development of CAD [

40]. Plaque content contains chemokines such platelet factor 4-5, and platelet activation has also been shown to actively contribute to plaque formation [

41,

42]. In our study, high NLR values in the ischemic group were statistically significant in multivariate analysis, in agreement with the literature. However, contrary to expectations, platelet count was lower in the ischemic group in univariate analysis and not statistically significant in multivariate analysis. This finding may be explained by the established invers relationship between albumin and platelet levels, with increased albumin levels having been shown to decrease platelet reactivity and prevent thrombosis [

6]. The predictive capacity of SII, though statistically significant, was more modest (AUC 0.588) compared to NPS. This might reflect differences in the inflammatory mechanisms driving stable versus acute CAD. While SII has demonstrated prognostic value in acute coronary syndromes, its role in chronic ischemia appears less pronounced in this study. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that neutrophil-predominant inflammation may be more relevant to ischemia detection in stable CAD. These findings underscore the need for context-specific biomarker selection based on disease acuity and phenotype. Our results extend prior work on inflammatory indices such as the CAR, NLR and SII, which have shown promise in risk stratification but lack the nutritional dimension incorporated in NPS [

32,

34,

37,

39].

From a clinical perspective, the accessibility of NPS and SII makes them practical tools for risk stratification. Incorporating these indices into the assessment of patients with SAP may enhance the identification of high-risk individuals who may benefit from intensified medical therapy or earlier referral for advanced imaging. For instance, patients with high NPS may be prioritized for closer follow-up or a targeted nutrition and early intervention approach.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, because of the retrospective design, we cannot determine cause-and-effect relationships, and it may overlook other factors that could affect the results, like differences in diet or unreported health issues. Second, the single-center cohort limits generalizability, and validation in broader populations is essential. Third, the inherent multicollinearity between NLR and SII required us to create separate models, showing that these two indices reflect similar inflammatory processes. Future research should explore the longitudinal relationship between NPS, SII, and hard clinical endpoints, including mortality and revascularization outcomes. Further studies are also required to investigate how malnutrition and inflammation interact to drive ischemia, which could reveal new treatment targets.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study identifies NPS and SII as important novel biomarkers for myocardial funcitonal ischemia in patients with stable CAD. They integrate systemic inflammation and nutritional status into the assessment of myocardial ischemia. By incorporating these biomarkers into clinical practice, we can improve risk assessment and tailor treatment strategies, aiming to enhance outcomes for patients with SAP. It is crucial for future studies to confirm these findings in larger and diverse patient groups. Additionally, further research should investigate how interventions that target inflammation and nutrition can benefit high-risk patients, thereby improving our understanding of these biomarkers and their clinical significance.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics of Approval Statement

The study was approved by the local ethics committee [Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee], and the approval number is [17-2025/13]. The research complies with the guidelines set by the Declaration of Helsinki for human subjects.

Patient Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their inclusion in the study.

Permission to Reproduce Material from Other Sources

No material from other sources was reproduced in this manuscript. All content is original.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.; methodology, H.S., D.Y.Ö.; software, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; validation, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; formal analysis, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; investigation, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; resources, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; data curation, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S., D.Y.Ö.; writing—review and editing, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; visualization, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S., D.Y.Ö. and U.N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Ralapanawa, U.; Sivakanesan, R. Epidemiology and the magnitude of coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome: a narrative review. Journal of epidemiology and global health 2021, 11, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Hansson, G.K.; Atherothrombosis, L.T.N.o. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. Journal of the American college of cardiology 2009, 54, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montecucco, F.; Liberale, L.; Bonaventura, A.; Vecchiè, A.; Dallegri, F.; Carbone, F. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular outcome. Current Atherosclerosis Reports 2017, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateş, A.H.; Aytemir, K.; Koçyiğit, D.; Yalcin, M.U.; Gürses, K.M.; Yorgun, H.; Canpolat, U.; Hazırolan, T.; Özer, N. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with the severity and morphology of coronary atherosclerotic plaques detected by multidetector computerized tomography. Acta Cardiologica Sinica 2016, 32, 676. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, G.K.; Libby, P.; Tabas, I. Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. Journal of internal medicine 2015, 278, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davì, G.; Patrono, C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2007, 357, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of cardiology 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Leu, H.-B.; Su, C.-H.; Yin, W.-H.; Tseng, W.-K.; Wu, Y.-W.; Lin, T.-H.; Chang, K.-C.; Wang, J.-H. Association of low serum albumin concentration and adverse cardiovascular events in stable coronary heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology 2017, 241, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Hashizume, N.; Kanzaki, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Kozuka, A.; Yahikozawa, K. Prognostic significance of serum albumin in patients with stable coronary artery disease treated by percutaneous coronary intervention. Plos one 2019, 14, e0219044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizia, G.; Lieto, E.; Auricchio, A.; Cardella, F.; Mabilia, A.; Podzemny, V.; Castellano, P.; Orditura, M.; Napolitano, V. Naples prognostic score, based on nutritional and inflammatory status, is an independent predictor of long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2017, 60, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, S.; Patirelis, A.; Hardavella, G.; Santone, A.; Carlea, F.; Pompeo, E. The Naples prognostic score is a useful tool to assess surgical treatment in non-small cell lung cancer. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Xie, C.; Ren, K.; Xu, X. Prognostic value of the Naples prognostic score in patients with gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis. Nutrition and cancer 2023, 75, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çetin, Z.G.; Balun, A.; Çiçekçioğlu, H.; Demirtaş, B.; Yiğitbaşı, M.M.; Özbek, K.; Çetin, M. A novel score to predict one-year mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement, Naples prognostic score. Medicina 2023, 59, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitmez, M.; Ekingen, E.; Zaman, S. Predictive Value of the Naples Prognostic Score for One-Year Mortality in NSTEMI Patients Undergoing Selective PCI. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, O.; Suygun, H.; Mustu, M.; Karadeniz, F.O.; Ozer, S.F.; Senol, H.; Kaya, D.; Buber, I.; Karakurt, A. Is the Naples prognostic score useful for predicting heart failure mortality. Kardiologiia 2023, 63, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, A.; Genc, O.; Ozkan, E.; Goksu, M.M.; Ibisoglu, E.; Bilen, M.N.; Guler, A.; Karagoz, A. Impact of Naples prognostic score at admission on in-hospital and follow-up outcomes among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Angiology 2023, 74, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, E.; Erdogan, A.; Karagoz, A.; Tanboğa, I.H. Comparison of systemic immune-inflammation index and Naples prognostic score for prediction coronary artery severity patients undergoing coronary computed tomographic angiography. Angiology 2024, 75, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yang, X.-R.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.-F.; Sun, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.-M.; Qiu, S.-J.; Zhou, J. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2014, 20, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Wu, C.H.; Hsu, P.F.; Chen, S.C.; Huang, S.S.; Chan, W.L.; Lin, S.J.; Chou, C.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Pan, J.P. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) predicted clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. European journal of clinical investigation 2020, 50, e13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, E.A.; Gąsior, J.S.; Tuzimek, A.; Dąbrowski, M.; Jankowski, P. The Association between Serum Vitamin D concentration and new inflammatory biomarkers—systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response (SIRI)—in patients with ischemic heart disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, Y.; Erdöl, A.; Özbay, M.B.; Erdoğan, M. The Prognostic Role of the Systemic Inflammatory Index (SII) in Heart Failure Patients: Systemic Inflammatory Index and Heart Failure. International Journal of Current Medical and Biological Sciences 2023, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic, E.A.; Gąsior, J.S.; Tuzimek, A.; Paleczny, J.; Junka, A.; Dąbrowski, M.; Jankowski, P. Investigation of the associations of novel inflammatory biomarkers—systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI)—with the severity of coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome occurrence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Peterson, E.D.; Dai, D.; Brennan, J.M.; Redberg, R.F.; Anderson, H.V.; Brindis, R.G.; Douglas, P.S. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 362, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.H.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C. An EAPCI expert consensus document on ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries in collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. European heart journal 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes: developed by the task force for the management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European heart journal 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Toldo, S.; Mauro, A.G.; Cutter, Z.; Abbate, A. Inflammasome, pyroptosis, and cytokines in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2018, 315, H1553–H1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, G.K. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. New England journal of medicine 2005, 352, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamhane, U.U.; Aneja, S.; Montgomery, D.; Rogers, E.-K.; Eagle, K.A.; Gurm, H.S. Association between admission neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. The American journal of cardiology 2008, 102, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pacheco, H.; Amezcua-Guerra, L.M.; Sandoval, J.; Martínez-Sánchez, C.; Ortiz-León, X.A.; Peña-Cabral, M.A.; Bojalil, R. Prognostic implications of serum albumin levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The American journal of cardiology 2017, 119, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, B.; Zaher, M.; Weiserbs, K.F.; Torbey, E.; Lacossiere, K.; Gaddam, S.; Gobunsuy, R.; Jadonath, S.; Baldari, D.; McCord, D. Usefulness of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting short-and long-term mortality after non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The American journal of cardiology 2010, 106, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Jang, H.-J.; Oh, I.-Y.; Yoon, C.-H.; Suh, J.-W.; Cho, Y.-S.; Youn, T.-J.; Cho, G.-Y.; Chae, I.-H.; Choi, D.-J. Prognostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The American journal of cardiology 2013, 111, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbel, Y.; Finkelstein, A.; Halkin, A.; Birati, E.Y.; Revivo, M.; Zuzut, M.; Shevach, A.; Berliner, S.; Herz, I.; Keren, G. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is related to the severity of coronary artery disease and clinical outcome in patients undergoing angiography. Atherosclerosis 2012, 225, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arefnia, M.; Bayat, M.; Hosseinzadeh, E.; Basiri, E.A.; Ghodsirad, M.; Naghshineh, R.; Zamani, H. The predictive value of CRP/albumin ratio (CAR) in the diagnosis of ischemia in myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Hipertensión y Riesgo Vascular 2025.

- Sabanoglu, C.; Inanc, I. C-reactive protein to albumin ratio predicts for severity of coronary artery disease and ischemia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 7623–7631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, S.; Barutcu, A.; Gazi, E.; Tan, Y.; Turkon, H. The relationship between some complete blood count parameters and myocardial perfusion: A scintigraphic approach. World Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2015, 14, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unkun, T.; Fidan, S.; Derebey, S.T.; Şengör, B.G.; Aytürk, M.; Sarı, M.; Efe, S.Ç.; Alıcı, G.; Özkan, B.; Karagöz, A. The Value of Naples Prognostic Score in Predicting Ischemia on Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy. Koşuyolu Heart Journal 2024, 27, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, S.Ç.; Candan, Ö.Ö.; Gündoğan, C.; Öz, A.; Yüksel, Y.; Ayca, B.; Çermik, T.F. Value of C-reactive protein/albumin ratio for predicting ischemia in myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Molecular Imaging and Radionuclide Therapy 2020, 29, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, B.R.; Kaysen, G. Poor nutritional status and inflammation: serum albumin: relationship to inflammation and nutrition. In Proceedings of the Seminars in dialysis; 2004; pp. 432–437. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, M.; Erdöl, M.A.; Öztürk, S.; Durmaz, T. Systemic immune-inflammation index is a novel marker to predict functionally significant coronary artery stenosis. Biomarkers in medicine 2020, 14, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Schutt, R.C.; Hannawi, B.; DeLao, T.; Barker, C.M.; Kleiman, N.S. Association of immature platelets with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014, 64, 2122–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppinger, J.A.; Cagney, G.; Toomey, S.; Kislinger, T.; Belton, O.; McRedmond, J.P.; Cahill, D.J.; Emili, A.; Fitzgerald, D.J.; Maguire, P.B. Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood 2004, 103, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsilos, S.; Hunt, J.; Mohler, E.R.; Prabhakar, A.M.; Poncz, M.; Dawicki, J.; Khalapyan, T.Z.; Wolfe, M.L.; Fairman, R.; Mitchell, M. Platelet factor 4 localization in carotid atherosclerotic plaques: correlation with clinical parameters. Thrombosis and haemostasis 2003, 90, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).