Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Iatrou et al. (2021) introduced machine learning systems (MLS) in the prediction modelling for nitrogen topdressing fertilization in rice cultivation using big data collected from a variety of data sources.

- Karydas et al. (2023a) achieved to embed well-established crop-oriented precision fertilization modules in a pre-existing farm management information system (FMIS).

2. Study Area and Data Set

- Agronomic data, including field boundaries, cultivars, seeding dates and planting years; provided by the farmers.

- Soil data, containing the full range of physical and chemical properties measured in samples with laboratory analysis.

- Satellite imagery, including optical and radar types, or spectral indices extracted from the optical data.

- Meteorological data, focusing on total monthly rainfall and mean monthly temperature from meteorological stations, and weather anomalies predicted from relevant models.

- Yield data, either collected from monitors mounted on harvesters (as in the case of rice cultivation), or with post-harvesting measurements of samples of the collected fruits, or estimated from images; yield is measured in kilogram or tones per hectare.

3. Methods

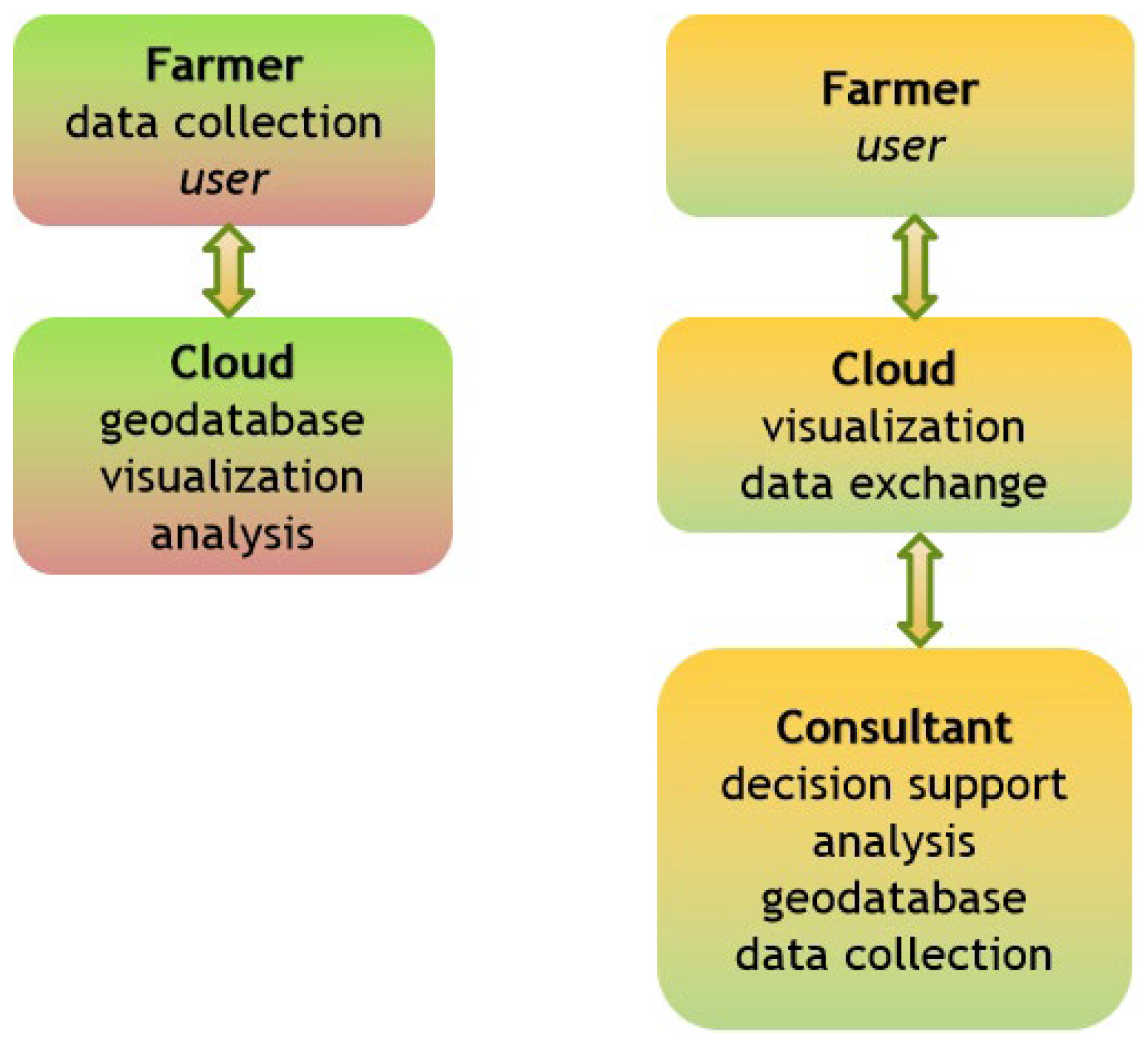

3.1. Overall

- A geographic information system (GIS), in the central role of data arrangement, ingestion, and process; it imports information from multiple sources, while it exports information to a farm management information system (FMIS) and to the variable-rate technologies (VRT) for the applications.

- A hub for soil and plant tissue data collection, comprising two nodes: the field survey teams for sample collection and the laboratory, where the samples are treated and analyzed.

- A hub for satellite image data collection, identical to a cloud platform, for downloading original or thematic values from earth observation imagers to preset point grid datasets.

- A hub for meteorological data collection, resulted from climatic models using satellite data enhanced with field data.

- A hub for yield data collection; it comprises the collection machinery, the data transfer, and the treatment within a GIS environment for data ingestion and analysis.

- A machine learning system (MLS) for big data analysis, comprising software, programming languages, and open-access mathematical libraries, especially for developing and enhancing prediction models for crop fertilization.

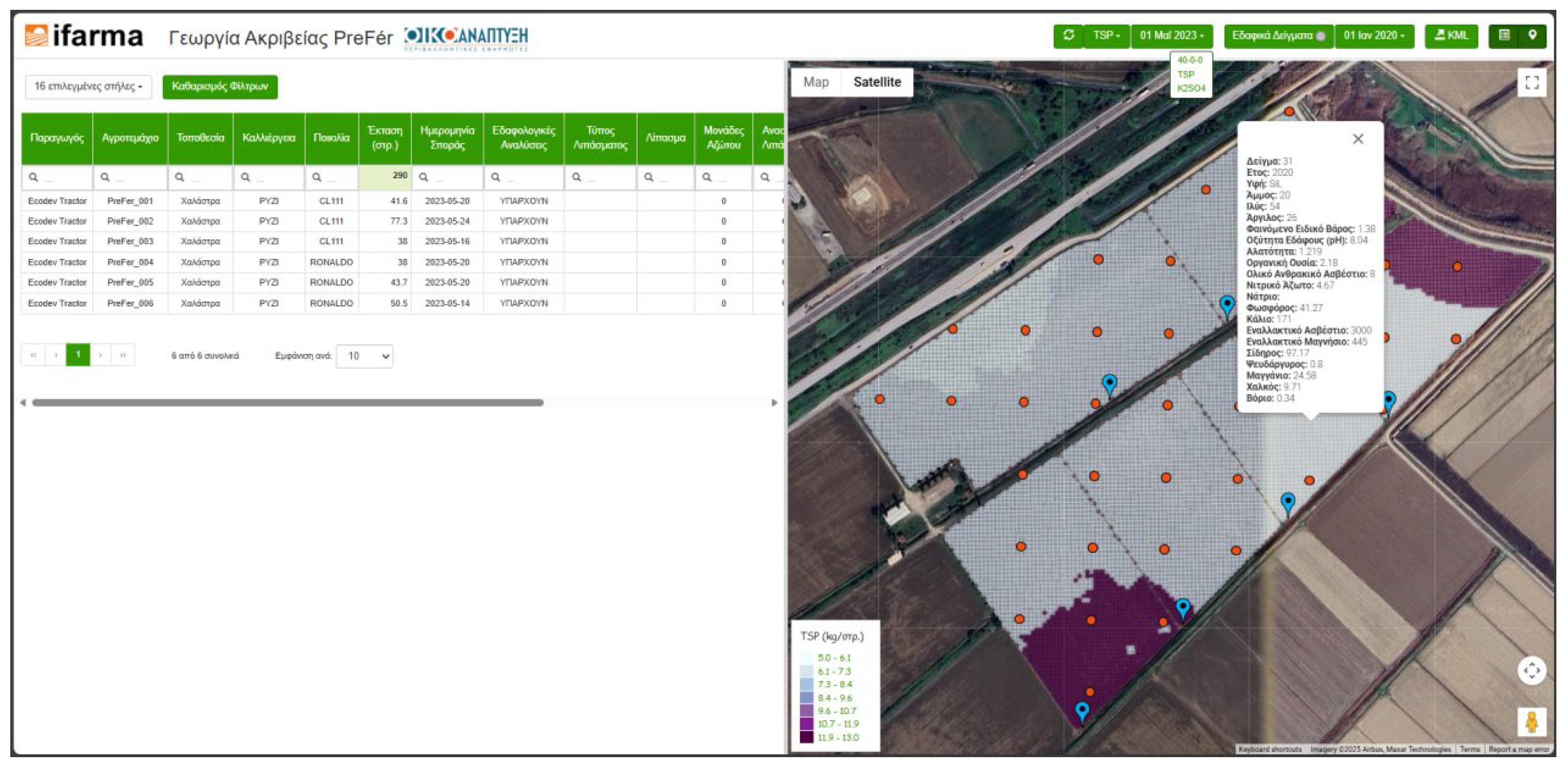

- A farm management information system (FMIS), as the farmers’ interface; used to collect, store and organize original farmers data (including LPIS data), provide agronomic data to the GIS, and visualize output map data.

- The available VRT systems, operated by the farmers. Each of these machines is the final receiver of the application maps.

- A Consultancy sub-process, dedicated to produce the fertilizer application maps, by running the prediction models per crop and growth stage (e.g., broadcasting, topdressing, etc.). This process associates GIS, MLS, and all the input data hubs (soil, satellite, yield, agronomic, etc.) into a data ingestion and analysis entity (denoted hereafter as ’shell’).

- A Communication sub-process, dedicated to store and visualize the map data, through an appropriate cloud-based platform, for the farmers. This process is realized between the GIS and the distinct extra modules developed and embedded on the FMIS system, in order to support the service .

- An Application sub-process, dedicated to transfer the application maps to the implementation machinery (e.g. VRT), through the appropriate data structure formats. This service is associated with the required equipment and potential solutions provided by the farmer’s side.

- The Consultancy process can be considered as an internal process, in terms of taking place within the data ingestion and analysis framework (denoted as ’shell’); whereas the Communication and Application processes as external ones, provided that they are associated with access and use of the outputs by the users. The overall process is described with a clear, integrated, and easy-to-follow service protocol.

3.2. The Geographic Information System (GIS)

- Data collection, transformation, and analysis of all data types and origin (historic data, remote sensing, field surveys, machinery, sensors, cloud, etc).

- Soil sampling design and preliminary zone delineation, according to detected variability in remote sensing or yield data.

- Ingestion of data from different sources, including reprojection, geometry repair, merging, unit conversions, filtering, cleansing, and calibration.

- Adaptation to farmer requirements and limitations, such as extraction of particular spectral indices, alternatives if not available machinery, etc.

- Scaling up and integration of data from different farmers, for conducting studies on soil sustainability or yield performance and profitability in an entire area.

3.3. Soil and Plant Tissue Data

3.4. Earth Observation Imagery

- Delineation of preliminary zones for soil sampling design with object-based classification.

- Regular plant growth monitoring with the extraction of appropriate spectral indices; this method replaced plant tissue analysis.

- A point shapefile, which represents the 5x5m grid, containing only a key-field, namely ’id’; and

- A polygon shapefile for the grid-containing region

- The above files must be entered in the scripts for allocating where exactly the data values will be assigned:

3.5. Meteorological Data

- ECMWF

- 51

- 2m temperature anomaly

- Ensemble: Mean

- [Month]

- 1,2,3,4

- [boundaries in degrees]

- NetCDF (experimental)

- Extract point values from raster

- Variable: t2a

- Band dimension: time

3.6. Yield Data

- Data collection, including recording in the field, transferring to the in-house process hub, insertion to the process system, and file structuring (e.g., recognition of attributes, unit conversions, etc.).

- Data ingestion, including reprojection and geometry repair (when sourced from yield monitors), merging (when from different sources), homogenization (matching common properties, common unit assignment, etc.), filtering (e.g., excluding values affected from unknown factors), cleansing (excluding abnormal values), and calibration (matching with reliable in-situ measurements).

- Data analysis, including descriptive statistics, correlation analysis (to other data types), and spatial auto-correlation (for spatial pattern recognition and possible zone delineation).

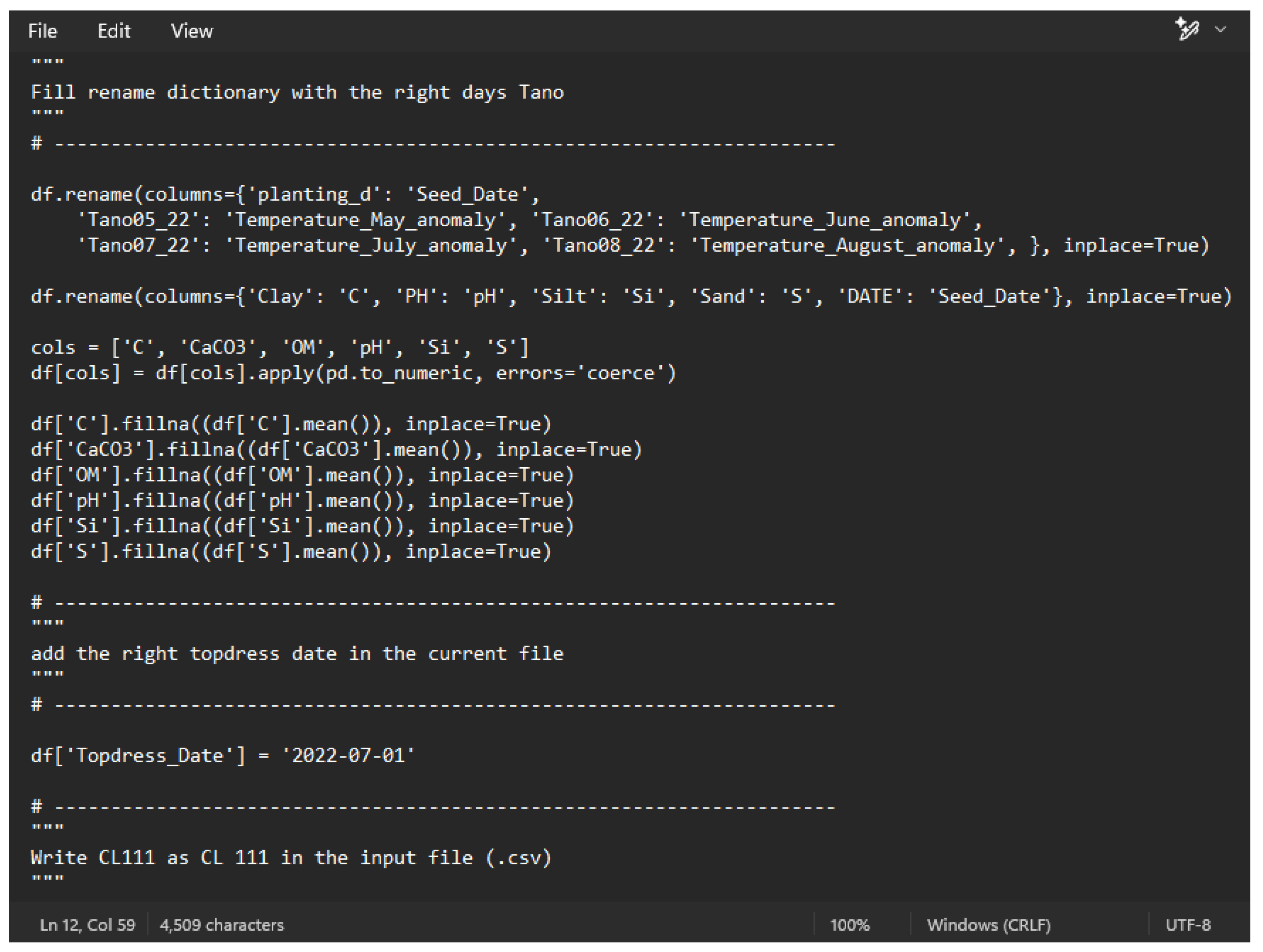

3.7. Machine Learning Systems

3.8. Farm Management Information System

3.9. Variable-Rate Technologies

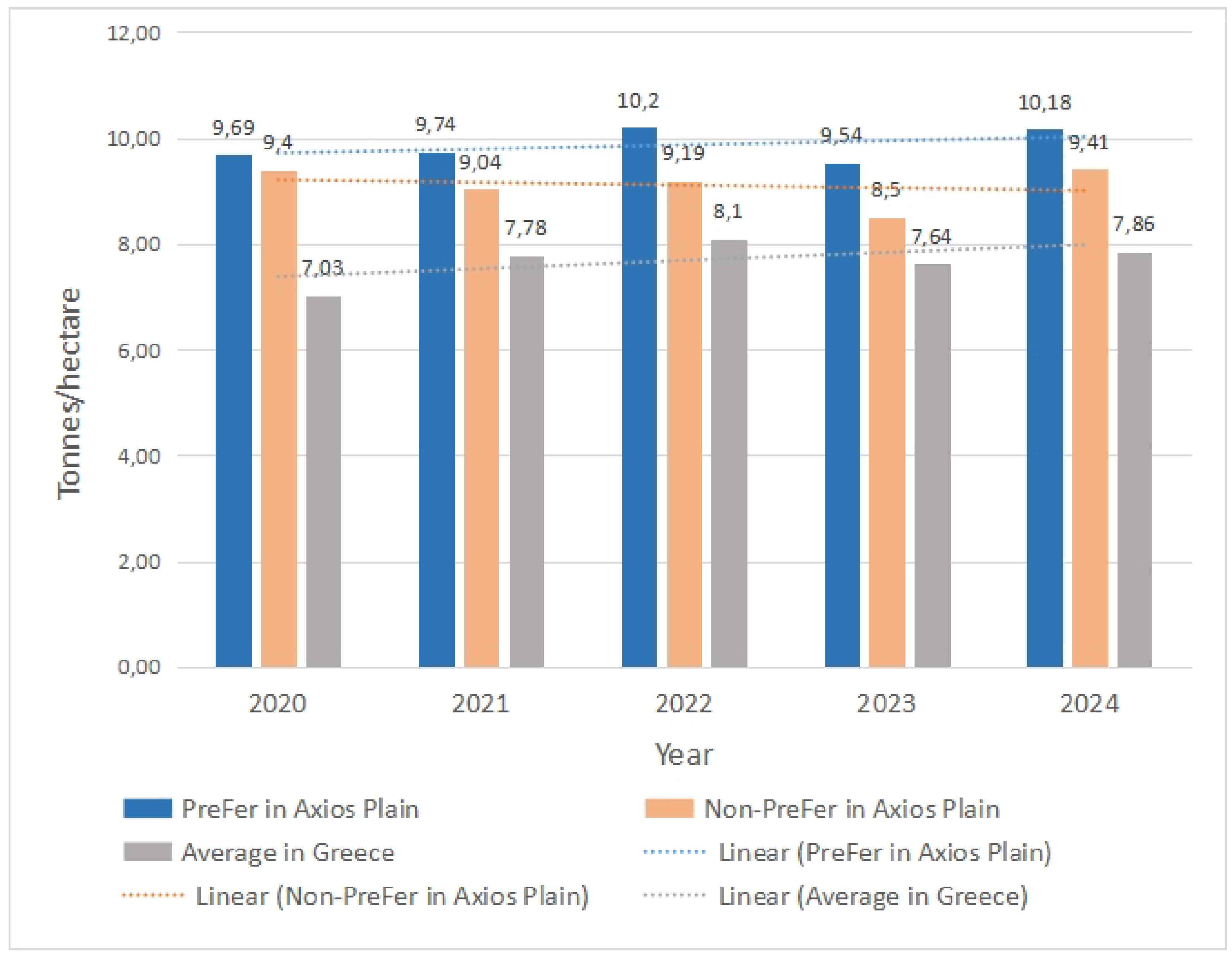

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Service History

4.2. Service Protocol

- Nine (9) descriptors related to GIS processes, specifically: symbols, formats, parcel layers, grid layers, soil layers, nutrient layers, fertilizer layers, VRT-maps, yield maps.

- Seven (7) descriptors related to F-models processes, specifically: general instructions, script for broadcasting fertilization in rice, script for topdressing fertilization in rice, script for cotton fertilization, script for maize fertilization, database (CSV) fields, script for Google Earth Engine.

- Eight (8) descriptors related to the ifarma FMIS, specifically: agronomic attributes, crops library, fertilizers library, soil layers, nutrient needs layers, satellite monitoring layers, fertilizer applications layers, yield maps layers].

4.2.1. Requirements

| Category | Resources |

|---|---|

| Software | |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | ArcGIS [commercial] QGIS [open] |

| Spreadsheet | Excel |

| Satellite data platform | Google Earth Engine (GGE) |

| Programming languages | Python JavaScript R |

| FMIS platform | Ifarma [commercial] |

| VRT-terminals | Trimble Ag [for map reference transformations] |

| Cloud data | |

| Earth Observation data | COPERNICUS Land Service SAR (Sentinel-1) Optical (Sentinel-2) |

| Meteorological data | MODIS ERA 5–land IMERG |

| Field data | |

| Soil samples | Soil surveys [Ecodevelopment S.A./Field Team] Soil analysis [ELGO-DIMITRA/SWRI Soil Labs] |

| Yield maps | Yield monitors [Any] |

4.2.2. Methodology

4.2.3. Symbology

| Nr. | Property | Data Type | Symbol | Indicative examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parcels | Polygon | p | R24_p |

| 2 | Grid[5x5m] | Point | g | CM1_g |

| 3 | Soil samples | Point | e | ALL20_e |

| 4 | Soil surfaces | Raster[5m] | S | ALL20_S |

| 5 | Soil surfaces | Point[grid] | s | ALL22_s |

| 6 | Nutrient needs | Point[grid] | n | AK23_n |

| 7 | Fertilizer applications | Point[grid] | fk : k=1,2,... | B21_f1 |

| 9 | Yield | Raster[5m] | Y | R23_Y |

| 10 | Yield | Point | y | R24_y |

| 11 | Plant growth | Image[10-20m] | [specral index] | LNC_YYYYMMDD |

4.2.4. Automations

4.3. Service Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Allen, R.G.; Walter, I.A.; Elliott, R.; Howell, T.; Itenfisu, D.; Jensen, M. The ASCE Standardized Reference Evapotranspiration Equation; Final Report (ASCE-EWRI); Environmental and Water Resources Institute (EWRI)/American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2005.

- Aschonitis, V.G.; Papamichail, D.; Demertzi, K.; Colombani, N.; Mastrocicco, M.; Ghirardini, A.; Castaldelli, G.; Fano, E.-A. High-resolution global grids of revised Priestley-Taylor and Hargreaves-Samani coefficients for assessing ASCE-standardized reference crop evapotranspiration and solar radiation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 615–638. [CrossRef]

- Aschonitis, V.G., Karydas, C.G., Iatrou, Μ., Mourelatos, S., Metaxa, I., Tziachris, P., Iatrou, G. (2019). An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Soil Quality and Nutritional Status of Large and Long-Term Cultivated Rice Agro-Ecosystems. Agriculture 9(80). [CrossRef]

- Burrough, P.A. and McDonnell, R.A. (1998). Principles of Geographical Information Systems. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment, 2025: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/descriptor.

- Chlingaryan, A.; Sukkarieh, S.; Whelan, B. Machine Learning Approaches for Crop Yield Prediction and Nitrogen Status Estimation in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 61–69.

- DeLay, N.D., Thompson, N.M. and Mintert, J.R. (2022), Precision agriculture technology adoption and technical efficiency. J Agric Econ, 73: 195-219. [CrossRef]

- ERA5-Land: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land?tab=overview.

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [CrossRef]

- Fountas, S., Carli, G., Sørensen, C.G., Tsiropoulos, Z., Cavalaris, C., Vatsanidou, A., Liakos, B., Canavari, M., Wiebensohn, J., Tisserye, B. Farm management information systems: Current situation and future perspectives. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Volume 115, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Fountas, S., Sorensen, C.G., Tsiropoulos, Z., Cavalaris, C., Liakos, V., Gemtos, T. Farm machinery management information system, Comput. Electron. Agric. 110 (2015) 131–138. [CrossRef]

- Fulton,J.;Hawkins, E.; Taylor, R.; Franzen, A. “Yield Monitoring and Mapping” in “Precision Agriculture Basics”. American Society of Agronomy, Inc., Crop Science Society of America, Inc., Soil Science Society of America, Inc, 2019, ISBN: 978-0-89118-366-2 (print), ISBN: 978-0-89118-367-9 (online). [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research, 2024; Report: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/precision-farming-market.

- Johannsen, C.J.; Carter, P.G. SITE-SPECIFIC SOIL MANAGEMENT, Editor(s): Daniel Hillel, Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, Elsevier, 2005, Pages 497-503, ISBN 9780123485304. [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Iatrou, G.; Zartaloudis, Z.; Kravvas, K.; Mourelatos, S. (2018). Optimization of fertilization recommendation in Greek rice fields using precision agriculture. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 19, 64–75.

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Iatrou, G.; Pitsiorlas, I.; Aschonitis, V.; Raptis, I.; Mpetas, S.; Kravvas, K.; Mourelatos, S. Topdressing Nitrogen Demand Prediction in Rice Crop Using Machine Learning Systems. Agriculture 2021, 11, 312. [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Tseni, X.; Mourelatos, S. Representation Learning with a Variational Autoencoder for Predicting Nitrogen Requirement in Rice. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5978. [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Iatrou, M.; Iatrou, G.; Mourelatos, S. (2020). Management Zone Delineation for Site-Specific Fertilization in Rice Crop Using Multi-Temporal RapidEye Imagery. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2604. [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Iatrou, M.; Kouretas, D.; Patouna, A.; Iatrou, G.; Lazos, N.; Gewehr, S.; Tseni, X.; Tekos, F.; Zartaloudis, Z.; Mainos, E.; Mourelatos, S. (2020). Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Cherry Fruits from UAS Multispectral Imagery Using Machine Learning. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 156. [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C., Chatziantoniou, M., Stamkopoulos, K., Iatrou, M., Vassiliadis, V., Mourelatos, S. (2023). Embedding a new precision agriculture service into a farm management information system - points of innovation. Smart Agricultural Technology, 4, 100175.

- Karydas, C.; Chatziantoniou, M.; Tremma, O.; Milios, A.; Stamkopoulos, K.; Vassiliadis, V.; Mourelatos, S. (2023) Profitability Assessment of Precision Agriculture Applications—A Step Forward in Farm Management. Applied Sciences, 13, 9640. [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C., 2025: Precision Agriculture definition.

- Labarthe, P. and Beck, M. (2022). CAP and Advisory Services: From Farm Advisory Systems to Innovation Support. EuroChoices, 21: 5-14. [CrossRef]

- ML Journey [website], 2025: https://mljourney.com/information-retrieval-system-examples/.

- Paraforos, D.S., Vassiliadis, V., Kortenbruck, D., Stamkopoulos, K., Ziogas, V., Sapounas, A.A., Griepentrog, H.W., (2017). Multi-level automation of farm management information systems, Comput. Electron. Agric. 14, 504–514. [CrossRef]

- PrecisionAG. ISPA Forms Official Definition of ‘Precision Agriculture’. 2019. Available online:https://www.precisionag.com/market-watch/ispa-forms-official-definition-of-precision-agriculture/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- SAP, website: https://www.bing.com/search?q=process+chain&FORM=AWRE.

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [CrossRef]

- Sood, K., Singh, S., Rana, R., Rana, A., Kalia, V., Kaushal, A. (2015). Application of GIS in precision agriculture. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2221.3368.

- Whelan, B. & Taylor, J. Precision Agriculture for Grain Production Systems. Field Crops Res. 2013, 155, 133.S.

| Service | Data | Zone delineation | Consultancy | Applications | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase, level | Sources, volume | Methods, scale | Methods | Scheme, engineering | Crops, extents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).