1. Introduction

Vasopressin is a peptide hormone produced in the hypothalamus of the human brain and released into the bloodstream through the posterior pituitary gland; it is widely distributed in the brain. Vasopressin is a nonapeptide consisting of nine amino acids that act on the vasopressin receptor 2 (V2R) in the kidneys, contributing to water reabsorption. Therefore, it functions as an anti-diuretic hormone at low doses [

1,

2].

Furthermore, in the vascular walls, vasopressin exerts constrictive effects at higher doses through the vasopressin receptor 1a (V1aR), producing a pressor effect. Therefore, it is used to treat diabetes insipidus, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and sepsis [3-9].

After vasopressin is distributed in the bloodstream and brain, it is metabolized by peptide-degrading enzymes to produce various AVP fragments and metabolites. Reported AVP fragments include AVP (4-8), AVP (4-9), AVP (5-8), and AVP (5-9), among others [10-14]. AVP4-8 and AVP(4-9) fragments are characterized by a low affinity for V2R and a high affinity for V1aR. In addition, none of these fragments exhibit antidiuretic effects.

This study focuses on AVP (4-9). AVP (4-9) is a pentapeptide consisting of six amino acids [15-19]. There are chemically modified AVP (4-9) analogs [20-22]; however, neither AVP (4-9) nor its analogs have demonstrated antidiuretic or pressor effects in animal experiments. AVP (4-9) and its analogs are regarded as the most promising V1aR agonists and excellent candidates for enhancing brain waste clearance by promoting the glymphatic system (GLS). AVP (4-9) is a naturally occurring metabolite in the body, and its safety has been established. Further, aquaporin 4 (AQP4) expression is promoted in the brain tissue or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the presence of AVP (4-9) or its analog.

In the cranium, there is a flow of fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, with the CSF circulating throughout. CSF is produced in the choroid plexus within the brain's ventricles. After circulation around the brain and spinal cord, it is absorbed through arachnoid granulation into the sagittal sinus. Traditionally, CSF circulation has been understood to play a role in clearing waste products from the brain and spinal cord. However, the CSF circulation mainly cleanses waste from the surface of the brain and spinal cord, and the mechanisms underlying waste clearance within the brain parenchyma remain unclear [23.24]. It was long believed that the brain, unlike other organs and tissues, lacked a lymphatic system for waste removal.

The flow of water within the brain parenchyma was first elucidated in 2012 by Iliff and Nedergaard et al., who introduced the concept of the GLS [

25]. Using two-photon microscopy, their research group demonstrated that the majority of the CSF in the subarachnoid space circulates through the brain interstitium and eventually returns to the CSF. Water from the CSF in the perivascular spaces surrounding the penetrating arterioles flows into the brain interstitium via AQP4, a water channel located in astrocytes. This convective flow perfuses the brain tissue and is subsequently expelled through the perivascular spaces around venules via AQP4. In addition to this convective flow, waste products in the brain interstitium are reportedly cleared.

Anti-vasopressin antibodies have been reported to inhibit the memory and learning-enhancing effects of vasopressin, leading to impairment in memory consolidation [

26]. Furthermore, vasopressin deficiency or the inhibition of vasopressin function has been associated with cognitive decline.

Vasopressin antagonists have been shown to suppress AQP4 expression in brain edema studies. Marmarou's group demonstrated that SR49059, a selective V1a receptor antagonist, effectively inhibited brain edema in experiments involving traumatic brain injury and cerebral ischemia [27-29]. This vasopressin antagonist works by inhibiting V1aR activation and suppressing AQP4 expression, which, in turn, reduces cytotoxic (cellular) edema. By limiting AQP4 expression, the influx of water into astrocytes is reduced, and water movement into the brain tissue is curtailed, slowing the progression of brain edema. SR49059 is considered an effective therapeutic agent for brain edema.

In experiments involving traumatic brain injury and cerebral ischemia in rats, AVP concentrations in the blood, brain, and CSF increased following brain injury or ischemia, accompanied by V1aR activation. The data showed that V1aR expression increased five-fold, along with a corresponding five-fold increase in AQP4 expression. It has been suggested that both V1aR activation and AQP4 expression increase in a dose-dependent manner. This increase in AVP concentration appeared to exacerbate brain edema. Consequently, inhibiting the action of AVP is considered a crucial strategy for treating brain edema [27-29].

Notably, these findings suggest that AVP, a V1aR agonist, promotes an increase in AQP4 expression. While direct experimental evidence demonstrating AQP4 upregulation by AVP fragments remains limited, prior studies have clearly established that blocking vasopressin receptors suppresses AQP4 expression. Given the critical role of AQP4 in glymphatic function, it is reasonable to infer that AVP fragments could enhance glymphatic clearance via AQP4 upregulation. Furthermore, the glymphatic system has been proposed to mediate brain waste clearance through AQP4, as described by Nedergaard’s group [

25]. Our study uniquely bridges these two previously separate research areas—vasopressin signaling and glymphatic system function. If prior studies had already demonstrated that AVP fragments upregulate AQP4 and enhance glymphatic clearance, this study would not have been necessary. By establishing this novel connection, we provide a foundation for future pilot and large-scale studies investigating the therapeutic potential of AVP fragments in promoting brain waste clearance.

Brain waste includes substances such as amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, and other factors associated with neurodegenerative diseases. In youth, the balance between the production and clearance of these waste products in the brain is maintained; however, with aging, the efficiency of clearance gradually declines. The function of the GLS, a waste clearance mechanism in the brain, also declines with age. Consequently, waste accumulates in the brain, contributing to the progression of neurodegeneration and neuronal damage.

Before the "Aβ hypothesis," which is a prominent theory regarding the cause of Alzheimer's disease, there is the "brain waste clearance impairment hypothesis." According to this hypothesis, promoting the waste clearance function of the brain is a key strategy for the prevention and improvement of neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, enhancing the function of the GLS, which is responsible for clearing brain waste, is crucial. Therefore, which methods can enhance the GLS function? Nedergaard’s group, which proposed the GLS theory, reported that GLS function is significantly enhanced during sleep compared to wakefulness [30-34].

Xie et al. found that during sleep, the interstitial space in the brain expands by 60%, greatly increasing the clearance of Aβ [

35]. Sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality are important factors that accelerate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression. Perras et al. reported that intranasal administration of AVP increased total sleep time, enhanced slow-wave sleep, which is deep sleep, and improved sleep structure in elderly individuals [

36]. Increased AQP4 expression is essential for the activation of GLS function. However, few practical AQP4 agonists are currently available. Nevertheless, as discussed in brain edema research, AQP4 expression is promoted by the activation of V1aR. The use of V1aR agonists induces AQP4 expression. As mentioned in the earlier studies by Marmarou et al., AVP is one such V1aR agonist [27-29].

Current therapeutic strategies for AD primarily focus on anti-amyloid antibodies based on the widely accepted “Aβ hypothesis." However, the clinical effectiveness of these treatments is limited, and alternative approaches are needed. However, because AVP has antidiuretic and pressor effects at higher doses, it may not be suitable for direct use as a GLS activator to promote brain waste clearance. Therefore, AVP fragments without antidiuretic or pressor effects may be useful as V1aR agonists. It is believed that as long as AVP (4-9) or its analogs reach the brain tissue or CSF, they promote AQP4 expression in the brain. Intranasal administration, which avoids the blood-brain barrier (BBB), is considered an effective drug delivery method. This small-scale study was conducted to investigate the extent of Aβ reduction in the brain following nasal spray administration of an AVP4-9 fragment analog, as well as its effects on cognitive function.

2. Method

This study was conducted as a pre-pilot exploratory investigation to evaluate the feasibility, directionality, and potential efficacy of AVP (4–9) fragment analog administration in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Due to financial and logistical constraints, the sample size was limited to seven participants who provided informed consent: three healthy adults (two males and one female) and four adults with AD (two males and two females). Each participant received intranasal administration of AVP (4-9) fragment analogs via nasal spray for two weeks. Based on the Nose-to-Brain hypothesis, a dose of 60 ng (0.4 mL/day, aqueous solution dissolved in physiological saline) of the AVP4-9 fragment analog was administered. The composite biomarker (CB) values were measured in the laboratory of Shimadzu Corporation using the method reported by Nakamura and Kaneko [

37].

Regarding the measurement of CB values, blood samples were collected and centrifuged within 5 minutes according to the testing instructions of Shimadzu Corporation's laboratory. After centrifugation for 15 minutes, only the serum was collected (3 mL) and stored frozen at temperatures below -20°C. The frozen samples were then transported under freezing conditions to Shimadzu Corporation's laboratory for measurement. This study is my own research and is not a collaborative study with Shimadzu Corporation. The CB value measurements were conducted at Shimadzu Corporation as a paid service.

The accumulation of Aβ in the brain before and after the two-week administration was evaluated using composite biomarker (CB) values, a blood-based biomarker. The CB values correlate with Aβ accumulation in the brain as measured by amyloid PET, with a diagnostic accuracy of 90%.

Rationale for Using CB Values Instead of Amyloid PET

Amyloid PET is widely regarded as the gold standard for detecting Aβ accumulation in the brain. However, its applicability in short-term therapeutic evaluations, such as in this study, is limited due to several methodological constraints. One major concern is the persistence of labeled molecular tracers that bind to amyloid plaques. While PET imaging effectively visualizes Aβ deposition, the exact duration of tracer binding remains uncertain. If pre-existing labeled tracers continue to bind to Aβ even after drug administration, subsequent PET scans may not accurately reflect changes in Aβ accumulation over a short period. Given that this study involved only a two-week treatment period, the potential persistence of bound tracers could lead to misinterpretation of Aβ clearance dynamics.

Furthermore, the use of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers was considered but ultimately deemed impractical due to the challenges associated with lumbar puncture in elderly patients. Age-related conditions such as degenerative lumbar spondylosis can make the procedure technically difficult, increasing the risk of unsuccessful attempts. Additionally, lumbar puncture can cause significant discomfort, making repeated sampling impractical for short-term studies like this one.

Given these considerations, CB values were selected as the primary biomarker for assessing Aβ accumulation. Previous studies have demonstrated that this blood-based biomarker correlates strongly with amyloid PET findings and offers high diagnostic accuracy. By utilizing CB values, we aimed to obtain a reliable and non-invasive measure of Aβ accumulation that is more suitable for evaluating short-term therapeutic effects.

In addition, cognitive function in adults with AD was assessed before and after administration using the ADAS-Cog score, a widely used tool for cognitive function assessment. The ADAS-Cog is frequently used to evaluate the efficacy of dementia drugs, as it measures various cognitive domains typically affected by Alzheimer's disease. These findings are statistically analyzed using a t-test.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with a strong emphasis on ethical considerations for all research participants. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, methods, potential risks, and benefits. Informed consent was obtained voluntarily, with detailed explanations covering the protection of personal information, risk management, compensation for potential losses, and assurances that participation was entirely voluntary, with no disadvantages for those who chose not to participate. For participants with dementia, consent was obtained from both the individuals and their families. Additionally, comprehensive measures were taken to protect participant privacy and ensure proper data management. All ethical considerations typically required for clinical trials were thoroughly explained and implemented.

3. Result

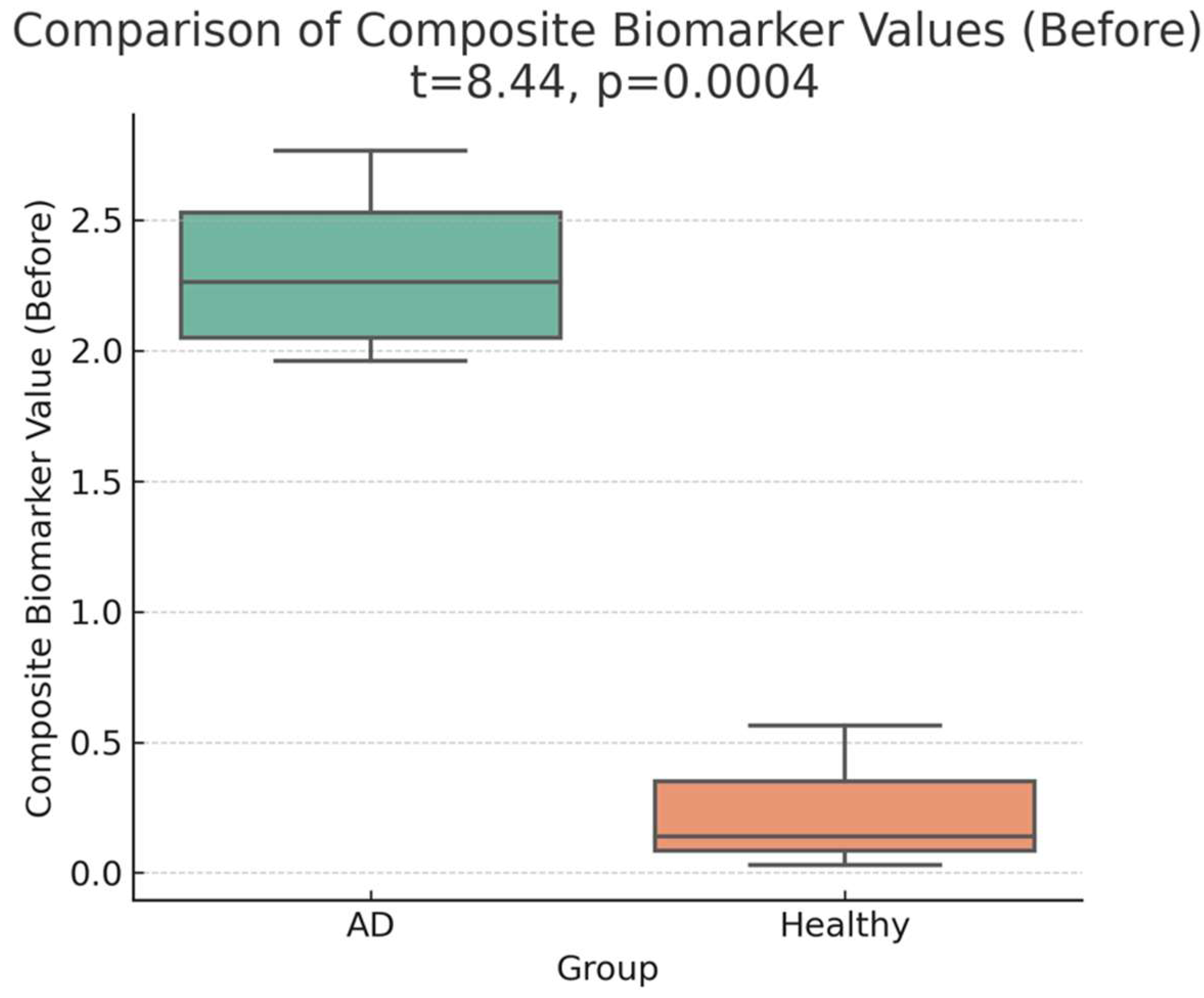

A marked difference was observed between the pre-administration CB values of four adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and three healthy adults. The CB values in the AD group were 9–40 times higher than those in healthy adults, highlighting a pronounced distinction between the two groups.

Table 1 presents the composite biomarker (CB) values for four AD patients (Cases 1–4) and three healthy adults (Cases 5–7) before treatment and two weeks later. At baseline, the mean CB value for the AD group was

2.31 (95% CI: 1.73–2.90), whereas the mean CB value for the healthy group was

0.24 (95% CI: −0.46–0.94). This difference was statistically significant (

t(5) = 8.71, p = 0.00040, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 3.92), corresponding to a

9.47-fold increase in CB values in the AD group (

Table 1; Figures 1-a, 1-b). The statistical power for this comparison was

98.5%, indicating strong evidence for the baseline group differences.

Table 1.

Composite Biomarker Value.

Table 1.

Composite Biomarker Value.

| |

sex |

before |

2 weeks later |

| Case 1 |

F |

2.767 |

2.446 |

| Case 2 |

F |

1.961 |

1.707 |

| Case 3 |

M |

2.449 |

0.846 |

| Case 4 |

M |

2.078 |

0.925 |

| Case 5 |

M |

0.138 |

-0.358 |

| Case 6 |

M |

0.564 |

0.297 |

| Case 7 |

F |

0.031 |

0.15 |

Figure 1.

a:Baseline distribution of composite biomarker (CB) values in the four AD patients (Cases 1–4) and three healthy adults (Cases 5–7). Visual inspection indicates a marked difference between the two groups before treatment, with higher CB values in the AD group.

Figure 1.

a:Baseline distribution of composite biomarker (CB) values in the four AD patients (Cases 1–4) and three healthy adults (Cases 5–7). Visual inspection indicates a marked difference between the two groups before treatment, with higher CB values in the AD group.

Figure 1.

b: Statistical Representation of Composite Biomarker Values (Before Treatment). The figure shows a marked difference between AD patients (Cases 1–4) and healthy adults (Cases 5–7), with the AD group displaying significantly elevated CB levels (p < 0.001). This observation highlights a pronounced baseline distinction between the two groups.

Figure 1.

b: Statistical Representation of Composite Biomarker Values (Before Treatment). The figure shows a marked difference between AD patients (Cases 1–4) and healthy adults (Cases 5–7), with the AD group displaying significantly elevated CB levels (p < 0.001). This observation highlights a pronounced baseline distinction between the two groups.

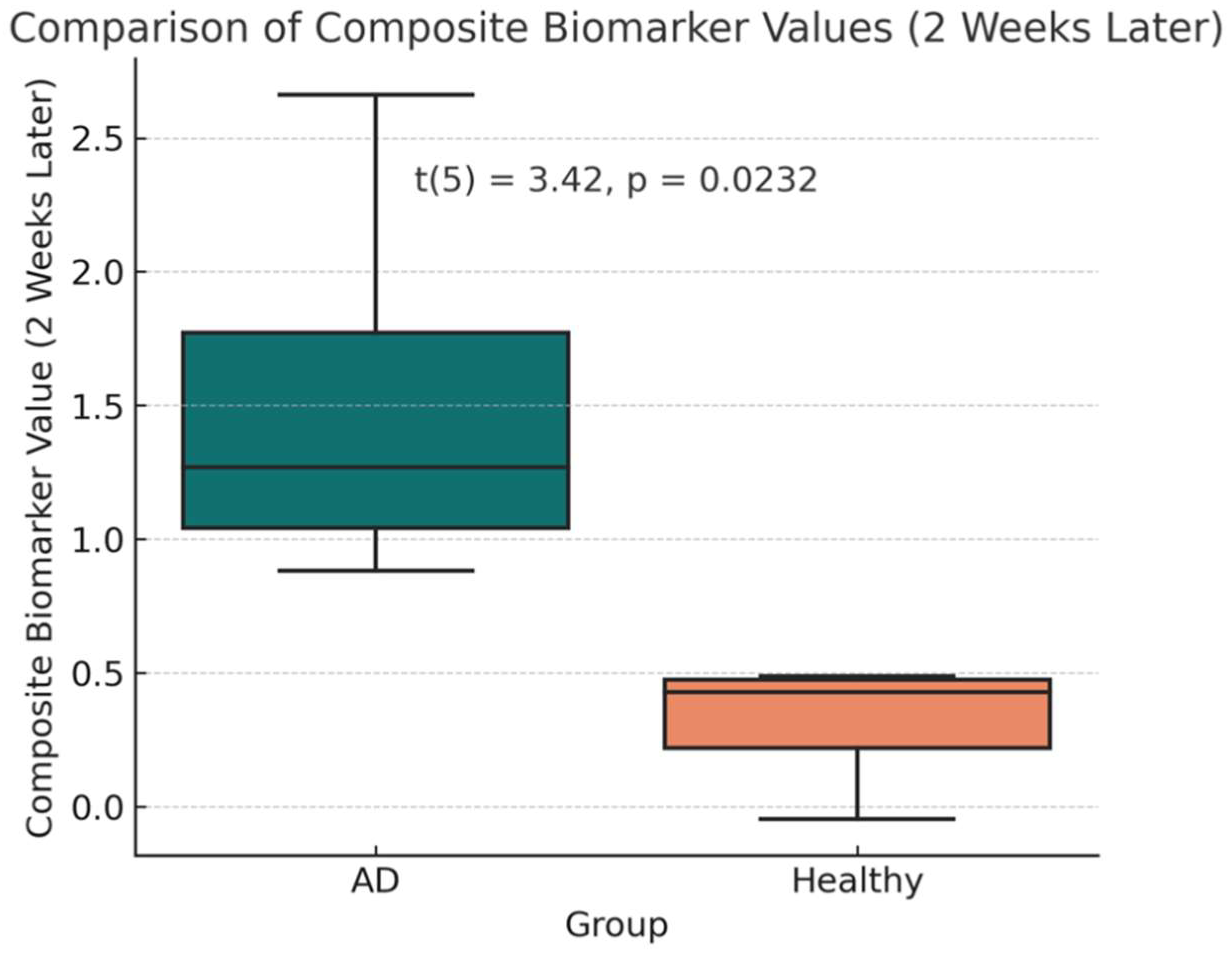

After two weeks of treatment with the AVP (4–9) fragment analog, the mean CB value in the AD group decreased to 1.48 (95% CI: 0.29–2.68), reflecting a significant reduction from baseline (t(3) = 2.515, p = 0.0460, mean difference = 0.568 ± 0.597; Figures 1-c, 1-d). This corresponds to an average reduction rate of 36.37% in CB values among AD patients. However, CB values in the AD group remained significantly higher than those in the healthy controls (t(5) = 3.42, p = 0.0232, Welch’s t-test). Power analysis indicated that this comparison had an observed power of 75.6%, while the statistical power for the paired t-test assessing CB reduction in AD patients was 55.9%, indicating the need for a larger sample size to strengthen the reliability of the findings., suggesting moderate confidence in the post-treatment difference.

Figure 1.

c: Statistical Summary of Composite Biomarker Values (2 Weeks Later). This figure shows that although AD patients (Cases 1–4) experienced a reduction in CB values from baseline, they remained significantly higher than those of healthy controls (Cases 5–7), as indicated by Welch’s t-test (p = 0.0232).

Figure 1.

c: Statistical Summary of Composite Biomarker Values (2 Weeks Later). This figure shows that although AD patients (Cases 1–4) experienced a reduction in CB values from baseline, they remained significantly higher than those of healthy controls (Cases 5–7), as indicated by Welch’s t-test (p = 0.0232).

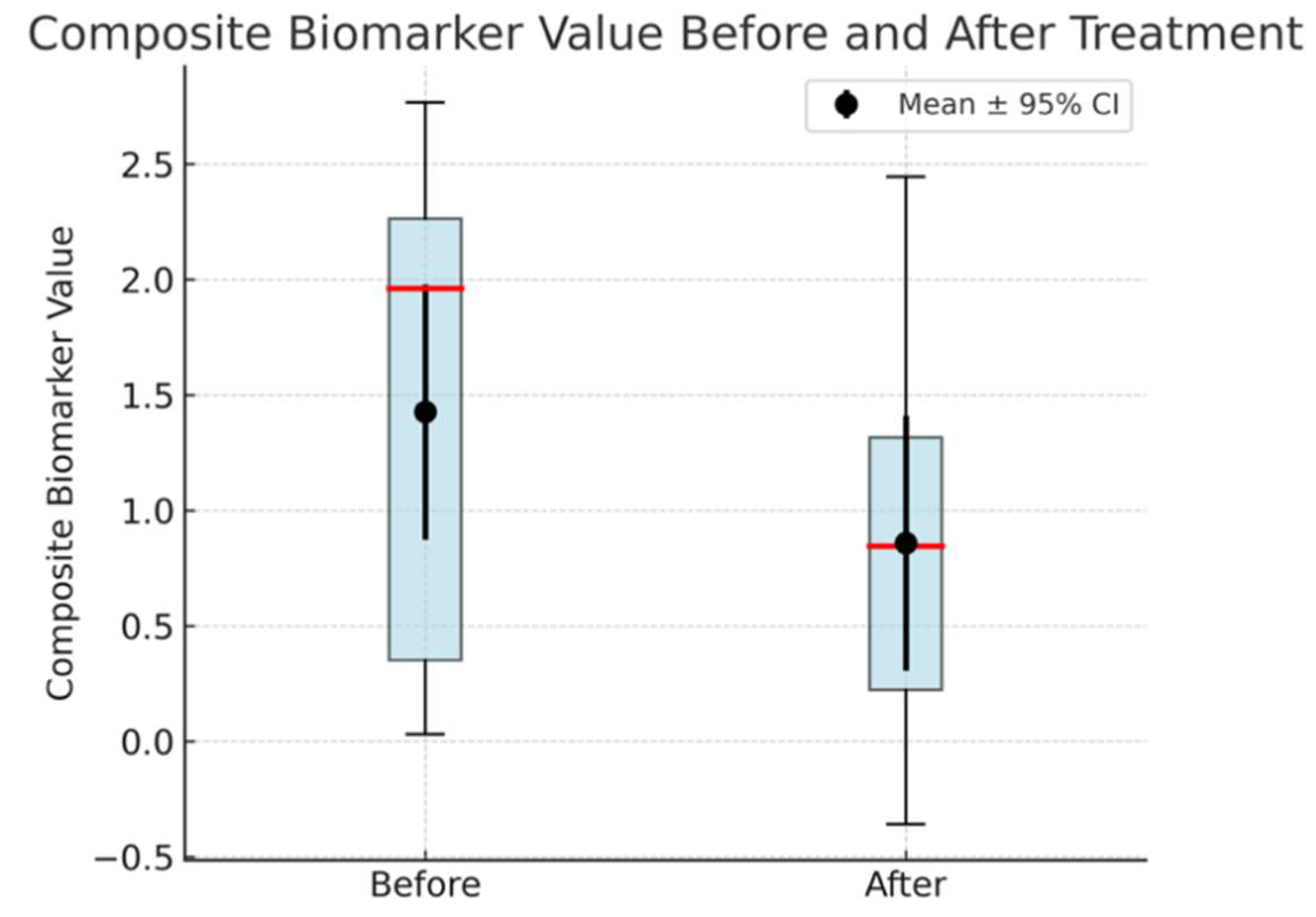

Figure 1.

d: Box plot showing CB values in AD patients (Cases 1–4) before and after drug administration. The red line denotes the median, the box represents the IQR, and the black dots with error bars indicate the mean ± 95% CI, all of which highlight a statistically significant reduction in CB values (p = 0.046) following treatment.

Figure 1.

d: Box plot showing CB values in AD patients (Cases 1–4) before and after drug administration. The red line denotes the median, the box represents the IQR, and the black dots with error bars indicate the mean ± 95% CI, all of which highlight a statistically significant reduction in CB values (p = 0.046) following treatment.

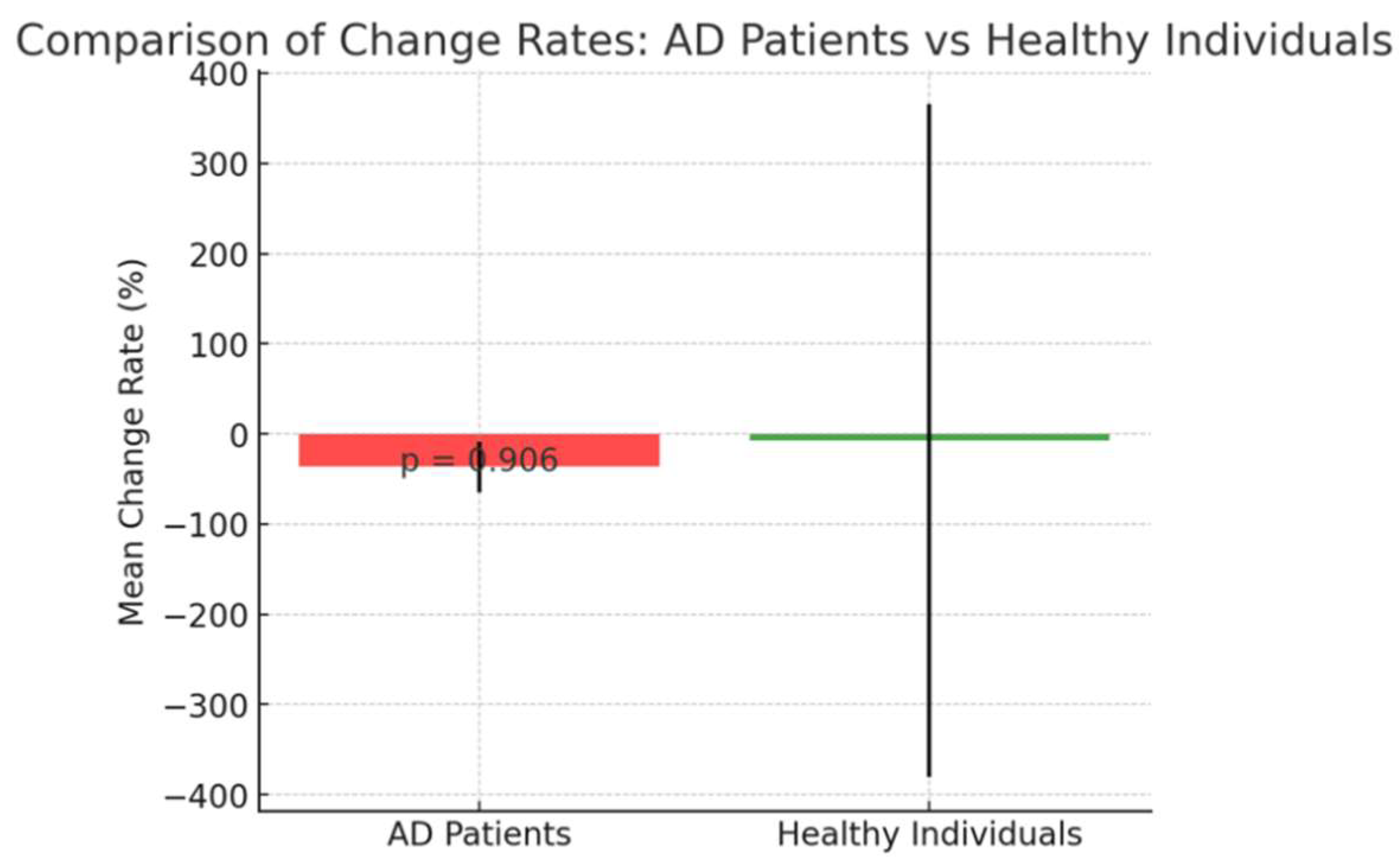

Change rates between Before and After is shown below. (

Figure 1-e).

The percentage change in CB values between baseline and two weeks post-treatment showed no significant difference between AD patients(Cases 1–4) and healthy individuals(Cases 5–7) (t(5) = 0.12, p = 0.9060; Figure 1-e), suggesting that both groups experienced a similar rate of CB reduction, implying a broadly consistent treatment effect across groups.

Figure 1.

e: Comparison of the percentage change in CB values from baseline to two weeks for AD patients (Cases 1–4) and healthy individuals (Cases 5–7). Bars represent mean change rates, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. There was no significant difference in the rate of change between the two groups (p = 0.906), implying a similar treatment effect.

Figure 1.

e: Comparison of the percentage change in CB values from baseline to two weeks for AD patients (Cases 1–4) and healthy individuals (Cases 5–7). Bars represent mean change rates, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. There was no significant difference in the rate of change between the two groups (p = 0.906), implying a similar treatment effect.

The CB values of both groups showed a significant difference in both the Before and After stages. Examination of the composite biomarker (CB) values in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Cases 1–4) before and after treatment revealed a statistically significant reduction. Box plots illustrate the distribution of these values, with the median indicated by the red line and the interquartile range (IQR) represented by the box. The black dots and accompanying error bars show the mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI), demonstrating an overall decrease in CB values following drug administration. A paired t-test confirmed this decline (t = 2.515, p = 0.046), yielding a mean difference of 0.568 ± 0.597 (mean ± SD) with a 95% CI spanning 0.015 to 1.120. While these results are encouraging, the statistical power (55.9%) indicates the need for a larger sample size to strengthen the reliability of the findings.

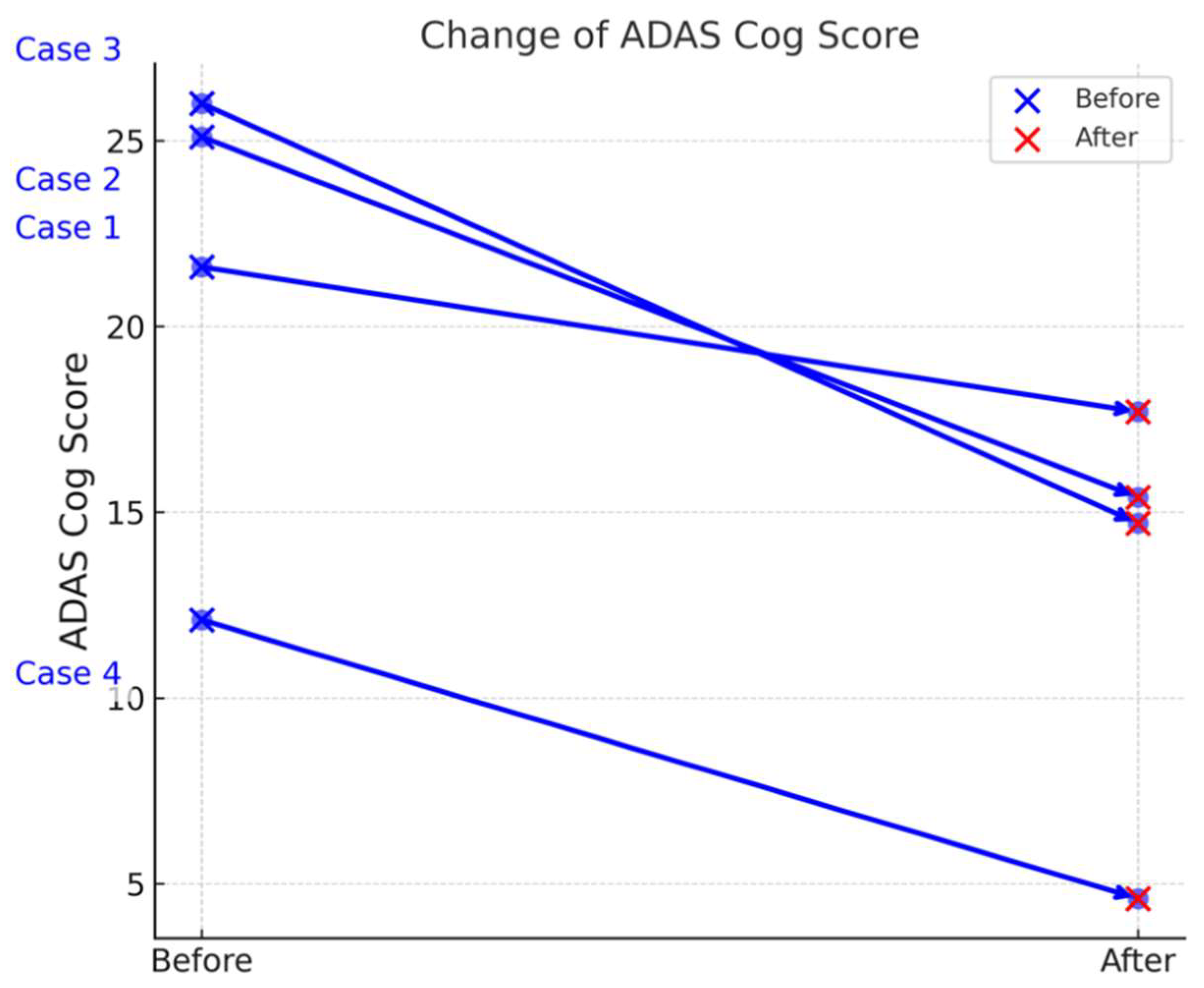

Statistical Analysis of ADAS-Cog Scores

Table 3 summarizes the ADAS-Cog scores of four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Cases 1–4) before and after treatment, revealing notable improvements in cognitive function. The mean reduction in ADAS Cog scores was 8.1 ± 3.204 (mean ± SD), with a 95% confidence interval of (3.001, 13.199). A paired t-test demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in ADAS Cog scores after drug administration (t = 5.056, p = 0.015) Table 2, Figures 2-a, 2-b). The statistical power of the analysis was 90.4%, indicating a high likelihood of detecting a true effect.

Table 2.

ADAS-Cog scores of four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients before and after treatment.

Table 2.

ADAS-Cog scores of four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients before and after treatment.

| Case No. |

Sex |

ADAS-Cog Score (Before) |

ADAS-Cog Score (After) |

| Case 1 |

F |

21.6 |

17.7 |

| Case 2 |

F |

25.1 |

15.4 |

| Case 3 |

M |

26 |

14.7 |

| Case 4 |

M |

12.1 |

4.6 |

Figure 2.

a: presents the individual ADAS-Cog scores for the four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Cases 1–4) at baseline and after two weeks of treatment. This visual representation shows that each patient experienced a decline in ADAS-Cog score, indicating an improvement in cognitive function over the treatment period. The differences among individual cases are evident, but all cases follow a downward trend, consistent with the overall statistical findings.

Figure 2.

a: presents the individual ADAS-Cog scores for the four Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Cases 1–4) at baseline and after two weeks of treatment. This visual representation shows that each patient experienced a decline in ADAS-Cog score, indicating an improvement in cognitive function over the treatment period. The differences among individual cases are evident, but all cases follow a downward trend, consistent with the overall statistical findings.

Figure 2.

b: Box plot illustrating the distribution of ADAS-Cog scores before and after drug administration in the four AD patients (Cases 1–4). The red line denotes the median, the box represents the interquartile range, and the black dots with error bars indicate the mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI). A paired t-test indicated a statistically significant improvement (t = 5.056, p = 0.015), supporting the drug’s potential efficacy in enhancing cognitive function.

Figure 2.

b: Box plot illustrating the distribution of ADAS-Cog scores before and after drug administration in the four AD patients (Cases 1–4). The red line denotes the median, the box represents the interquartile range, and the black dots with error bars indicate the mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI). A paired t-test indicated a statistically significant improvement (t = 5.056, p = 0.015), supporting the drug’s potential efficacy in enhancing cognitive function.

This study was conducted as a pre-pilot study due to insufficient financial support to fully guarantee a pilot study, resulting in a limited sample size. Similarly, the absence of a placebo group was also due to financial constraints. However, the measurement of CB values is not affected by the placebo effect, and regarding the ADAS-Cog Score, cognitive function in individuals with dementia typically does not change within two weeks, making it comparable to a placebo group. Thus, while we recognize the ideal importance of a placebo group, we do not believe its absence critically undermines the validity of this study. Therefore, the statistically significant data obtained in this study are valuable.

4. Discussion

This paper discusses the processes, theories, and logic leading to the hypothesis that vasopressin (AVP) fragments and their analogs may be useful in preventing or treating neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). To my knowledge, this is the first study to use vasopressin fragments for this purpose. By targeting the underlying causes of neurodegenerative diseases before the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), the findings offer a fresh perspective that could complement existing research.

The concentration of AVP in the cerebrospinal fluid decreases in AD and other neurodegenerative disorders [

38,

39,

40,

41]. This reduction in AVP may lead to decreased aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression, which could impair glymphatic system (GLS) function, potentially hindering the clearance of waste products such as Aβ and tau, resulting in their accumulation in the brain. While the "amyloid hypothesis" is currently the dominant theory regarding the mechanism of AD, there may also be a preceding "brain waste clearance impairment hypothesis." Furthermore, the decline in memory and learning functions caused by vasopressin deficiency in the brain may also be a contributing factor.

As demonstrated by Marmarou et al. in brain edema research, the activation of the vasopressin 1a receptor (V1aR) by AVP increases AQP4 expression. The GLS, proposed by Nedergaard et al., explains the influx of water molecules into the brain tissue via AQP4 and their subsequent efflux from the brain, which is also mediated by AQP4 [

25]. Water flow has been reported to facilitate the clearance of waste products from the brain. Similar to AVP, selective V1aR agonists such as AVP fragments promote AQP4 expression, enhance GLS function, and promote the clearance of brain waste, making them strong candidates as preventive or therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. An additional benefit of the AVP (4-9) fragment and its analogs is the absence of antidiuretic or pressor effects.

In this short-term, small-scale study, the AVP (4-9) fragment analog demonstrated a reduction in composite biomarker values, which reflect the accumulation of Aβ in the brain. Statistical analysis of composite biomarker (CB) values revealed that AVP (4-9) analog was equally effective in reducing Aβ accumulation in both AD patients and healthy controls, with no significant difference between the two groups.

Additionally, ADAS-Cog scores demonstrated significant cognitive improvement in AD patients, further supporting the broad applicability of AVP (4-9) analog as a therapeutic agent. This improvement is believed to result from the memory and learning enhancement effects of AVP, known as the "learning hormone," rather than from the promotion of glymphatic system (GLS) function. AVP exerts these effects by activating intracellular signaling via V1aR, which leads to the activation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), thereby promoting gene expression and the production of intracellular proteins [

42].These proteins contribute to synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation, both of which are fundamental to memory encoding and consolidation.

In the author's clinical experience, memory-enhancing effects of AVP analogs have been observed. A young male patient developed memory impairment after resection of a craniopharyngioma compressing the hypothalamus, leading to forgetfulness to the extent of forgetting meals. However, a significant improvement was observed following desmopressin administration. This AVP analog seems to play a role in improving memory. Although the AVP analog, desmopressin, primarily has an affinity for V2R, it also exhibits a slight affinity for V1aR, approximately 1/1000th that of V2R [

43]. This V1aR agonist activity may contribute to improvements in memory and learning.

AVP has long been known as the "learning hormone," with pioneering research conducted by Wied et al. from the mid-1970s to the 1980s. They reported that AVP has memory-enhancing effects and that anti-AVP antibodies inhibit these effects [26, 44–46]. Although AVP is not directly involved in memory recall (retrieval), it promotes synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation and plays a crucial role in memory encoding and consolidation. Therefore, AVP has gained attention as an effective substance in improving cognitive function.

Recent studies suggest that GLS dysfunction is a common feature across multiple neurodegenerative diseases, not limited to AD. Impaired waste clearance mechanisms have been implicated in tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), as well as in synucleinopathies like Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Likewise, transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) aggregation is a hallmark of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD-TDP) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Moreover, conditions such as Huntington’s disease—associated with aberrant huntingtin protein accumulation—and glaucoma, increasingly recognized as a neurodegenerative disorder, have also been linked to deficits in protein clearance.

Considering the convergence of impaired protein clearance mechanisms across neurodegenerative diseases, GLS activation via AVP fragments represents a potentially broad-spectrum therapeutic avenue beyond Alzheimer's disease.

Further research is necessary to elucidate the extent to which GLS activation contributes to the prevention or treatment of neurodegenerative diseases beyond AD. The next step is to investigate the long-term effects and potential clinical applications of AVP fragments, particularly in larger cohorts and across various neurodegenerative conditions.

5. Conclusion

This study identified a novel dual action of vasopressin (AVP) fragments, demonstrating both their well-established pro-cognitive effects—enhancing memory and learning—and their ability to activate the glymphatic system (GLS) to facilitate brain waste clearance. This dual mechanism highlights AVP fragments, including the AVP (4–9) fragment, as promising therapeutic candidates for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Larger and more diverse clinical trials are essential to confirm these findings and evaluate their clinical applicability.

Impaired clearance of neurotoxic waste products has been implicated in various neurodegenerative disorders. While this study focused on AD, its implications extend to other conditions characterized by pathological protein accumulation, such as tauopathies, synucleinopathies, and TDP-43-related disorders. Given the commonality of impaired clearance across these conditions, targeting GLS and related pathways may offer a broadly applicable therapeutic strategy.

In summary, AVP fragments offer a unique approach by combining cognitive enhancement with waste clearance activation, addressing two key pathological mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Future research should focus on rigorous clinical trials to establish their efficacy and safety, as well as elucidate the precise role of GLS activation in disease modification. Leveraging GLS stimulation as a therapeutic strategy has the potential to not only improve symptoms but also alter disease progression, providing a novel addition to the current treatment landscape for AD and related disorders.

Author Contributions

The sole author, J. Imamura, was responsible for the conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, as well as manuscript drafting and revisions. All aspects of the research and writing were conducted independently.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to all individuals who participated in and supported this study, including clinical staff and patients who provided valuable data and cooperation. Their contributions were essential for the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has declared that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AVP: Arginine Vasopressin, AVP 4-9: Vasopressin Fragment 4-9, GLS: Glymphatic system, AQP4: Aquaporin 4, CB: Composite Biomarker, ADAS-Cog: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale, Aβ: Amyloid Beta, V1aR: Vasopressin 1a Receptor, CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid, ADH: Antidiuretic hormone, BBB: Blood-Brain Barrier, AD: Alzheimer's Disease.

References

- Cuzzo B, Padala SA, Lappin SL.: Physiology, Vasopressin. 2023 Aug 14. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–.PMID: 30252325.

- S Sparapani, C Millet-Boureima, J Oliver: The biology of vasopressin Biomedicines, 2021 - mdpi.com [HTML].

- Carsten Lott, Anatolij Truhlář: European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation Volume 161, April 2021, Pages 152-219.

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 486–552. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.L.; Walley, K.R.; Chittock, D.R.; Lehman, T.; Russell, J.A. The effects of vasopressin on hemodynamics and renal function in severe septic shock: a case series. Intensiv. Care Med. 2001, 27, 1416–1421. [CrossRef]

- Gokhan MM, Phillip Factor: Role of vasopressin in the management of septic shock. Intensive Care Medicine. Volume 30, pages 1276–1291, (2004).

- Mitchell, S.L.M.; Hunter, J. Vasopressin and its antagonists: what are their roles in acute medical care?. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 154–158. [CrossRef]

- V Rozenfeld, JWM Cheng: The role of vasopressin in the treatment of vasodilation in shock states. Annals of Pharmacotherapy,Vol32(2)2000 - journals.sagepub.com.

- Treschan, T.A.; Peters, J.; Warltier, D.C. The Vasopressin System. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, 599–612. [CrossRef]

- Mishima, K.; Tsukikawa, H.; Miura, I.; Inada, K.; Abe, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Egashira, N.; Iwasaki, K.; Fujiwara, M. Ameliorative effect of NC-1900, a new AVP4–9 analog, through vasopressin V1A receptor on scopolamine-induced impairments of spatial memory in the eight-arm radial maze. Neuropharmacology 2003, 44, 541–552. [CrossRef]

- Maegawa, H.; Katsube, N.; Okegawa, T.; Aishita, H.; Kawasaki, A. Arginine-vasopressin fragment 4–9 stimulates the acetylcholine release in hippocampus of freely-moving rats. Life Sci. 1992, 51, 285–293. [CrossRef]

- Tadatsugu Tarumi Yukio Sugimoto.: Effects of metabolic fragments of [Arg8]-vasopressin on nerve growth in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Research Bulletin,50 2000,407-411.

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.-C. Cloning of cytidine triphosphate: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase mRNA upregulated by a neuropeptide arginine-vasopressin(4–8) in rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 2000, 283, 129–132. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, F.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M.; Yang, W.; Guo, J.; et al. AVP(4-8) Improves Cognitive Behaviors and Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity in the APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2019, 36, 254–262. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A.; Taylor, J.T.; E Passmore, C. AVP (4-8) improves concept learning in PFC-damaged but not hippocampal-damaged rats. Brain Res. 2001, 919, 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich A, Allen JD. (1997). Vasopressin and memory. I. The vasopressin analogue AVP(4-9) enhances working memory as well as reference memory in the radial arm maze. Behav Brain Res. 87(2):195-200.

- Chepkova, A.N.; Kapai, N.A.; Skrebitskii, V.G. Arginine vasopressin fragment AVP(4-9)facilitates induction of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus.. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2001, 131, 136–138. [CrossRef]

- Sato T, Ishida T, Tanaka K, Ohnishi Y, Irifune M, Mimura T, et al. (2005) . Ameliorative and exacerbating effects of [pGlu(4),Cyt(6)]AVP(4-9) on impairment of step-through passive avoidance task performance by group II metabotropic glutamate receptor-related drugs in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 97:437-442.

- Gaffori, O.; De Wied, D. Time-related memory effects of vasopressin analogues in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 25, 1125–1129. [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, M.; Ohgami, Y.; Inada, K.; Iwasaki, K. Effect of active fragments of arginine-vasopressin on the disturbance of spatial cognition in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 1997, 83, 91–96. [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Tanaka, K.-I.; Ohnishi, Y.; Teramoto, T.; Hirate, K.; Nishikawa, T. [The improvement of memory retention and retrieval of a novel vasopressin fragment analog NC-1900].. 2002, 120, 57P–60P.

- Sato, T.; Tanaka, K.-I.; Teramoto, T.; Ohnishi, Y.; Hirate, K.; Irifune, M.; Nishikawa, T. Effect of pretraining administration of NC-1900, a vasopressin fragment analog, on memory performance in non- or CO2-amnesic mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004, 78, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Czarniak, N.; Kamińska, J.; Matowicka-Karna, J.; Koper-Lenkiewicz, O.M. Cerebrospinal Fluid–Basic Concepts Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1461. [CrossRef]

- Proulx, S.T. Cerebrospinal fluid outflow: a review of the historical and contemporary evidence for arachnoid villi, perineural routes, and dural lymphatics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78, 2429–2457. [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111.

- de Wied D, van Wimersma Greidanus TB, Bohus B, Urban I, Gispen WH. (1976) Vasopressin and memory consolidation. Prog Brain Res. 45:181-194.

- Taya, K.; Gulsen, S.; Okuno, K.; Prieto, R.; Marmarou, C.R.; Marmarou, A. (2008) .Modulation of AQP4 expression by the selective V1a receptor antagonist, SR49059, decreases trauma-induced brain edema. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 102:425-429.

- Kleindienst, A.; Dunbar, J.G.; Glisson, R.; Marmarou, A. The role of vasopressin V1A receptors in cytotoxic brain edema formation following brain injury. Acta Neurochir. 2012, 155, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Marmarou, C.R.; Liang, X.; Abidi, N.H.; Parveen, S.; Taya, K.; Henderson, S.C.; Young, H.F.; Filippidis, A.S.; Baumgarten, C.M. Selective vasopressin-1a receptor antagonist prevents brain edema, reduces astrocytic cell swelling and GFAP, V1aR and AQP4 expression after focal traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014, 1581, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Jessen, N.A.; Munk, A.S.F.; Lundgaard, I.; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System: A Beginner’s Guide. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 2583–2599. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1016–1024. [CrossRef]

- Hablitz, L.M.; Vinitsky, H.S.; Sun, Q.; Stæger, F.F.; Sigurdsson, B.; Mortensen, K.N.; Lilius, T.O.; Nedergaard, M. Increased glymphatic influx is correlated with high EEG delta power and low heart rate in mice under anesthesia. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav5447. [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, M.; Goldman, S.A. Glymphatic failure as a final common pathway to dementia. Science 2020, 370, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Reddy OC, van der Werf YD. (2020). The sleeping brain: harnessing the power of the glymphatic system through lifestyle choices. Brain Sci. 10:868.

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Christensen, D.J.; Nicholson, C.; Iliff, J.J.; et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377.

- Perras, B.; Pannenborg, H.; Marshall, L.; Pietrowsky, R.; Born, J.; Fehm, H.L. Beneficial Treatment of Age-Related Sleep Disturbances With Prolonged Intranasal Vasopressin. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999, 19, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura A, Kaneko N, Villemagne VL, Kato T, Doecke J, Dore V, et al.: (2018) . High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 554:249-254.

- Sundquist, J.; Forsling, M.L.; E Olsson, J.; Akerlund, M. Cerebrospinal fluid arginine vasopressin in degenerative disorders and other neurological diseases.. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1983, 46, 14–17. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, P.S.; Gjerris, A.; Hammer, M. Cerebrospinal fluid vasopressin in neurological and psychiatric disorders.. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1985, 48, 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Lampe TH, Risse SC, Taborsky GJ, Dorsa D. (1986). Cerebrospinal fluid vasopressin, oxytocin, somatostatin, and beta-endorphin in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 43:382-388.

- Mazurek, M.F.; Growdon, J.H.; Beal, M.F.; Martin, J.B. CSF vasopressin concentration is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1986, 36, 1133–1133. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Brinton, R.D. Vasopressin-Induced Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Calcium Signaling in Embryonic Cortical Astrocytes: Dynamics of Calcium and Calcium-Dependent Kinase Translocation. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 4228–4239. [CrossRef]

- PMDA. (2019). "Application Summary Document for Minirin Melt OD Tablets 25 µg, 50 µg." Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency,.

- van Wimersma Greidanus TB, de Wied D. (1980). Physiological significance of neurohypophyseal hormones in memory processes. Acta Psychiatr Belg. 80:721-727.

- Laczi, F.; Gaffori, O.; De Kloet, E.; De Wied, D. Arginine-vasopressin content of hippocampus and amygdala during passive avoidance behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1983, 280, 309–315. [CrossRef]

- Gaffori, O.; De Wied, D. Time-related memory effects of vasopressin analogues in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 25, 1125–1129. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).