1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) ranks among the most common neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by a gradual decline in cognitive abilities and memory. Although the underlying mechanisms of AD remain partially understood, they involve the disruption of various metabolic pathways, with incidence rising as individuals age. A notable relationship exists between the advancement of AD and neuronal dysfunction [

1]. A major contributing factor to AD is the impaired degradation of misfolded proteins, resulting in the accumulation of β-amyloid and the formation of toxic deposits, which are hallmark characteristics of the disease [

2]. The neurotoxic effects of abnormal β-amyloid forms are associated with disturbances in calcium ion balance, interactions with cell membrane lipids, and the activation of specific receptors, leading to significant damage to glutamatergic neurons in the hippocampus and cortex.

Dysfunctional neurons are thought to release excessive glutamic acid, whose metabolites are toxic and can induce cell death. Under normal conditions, glutamate functions as a stimulant that regulates neurogenesis by activating nearby progenitor cells [

3]. Research in animals has shown that inhibiting glutamatergic signaling markedly decreases cell proliferation [

4]. Besides the glutamatergic system, the cholinergic system is also crucial for the generation of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus [

5]. Insights into the mechanism of acetylcholine hydrolysis inhibition at the synapse have facilitated the development of novel therapies for AD [

6]. Studies suggest that the slow neurodegenerative process may trigger neurogenesis. Although the exact mechanisms remain elusive, current investigations have concentrated on animal models and cell cultures [

7]. Proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases also play a role in regulating brain plasticity during developmental stages under normal conditions [

8].

Neurogenesis in the adult human brain differs from that in the fetus. Initially, it was believed that neurogenesis was restricted to prenatal and perinatal stages. This perspective shifted in 1965 when Joseph Altman and Gopal D. Das identified newly formed neurons in the brains of adult rats. Later, in 1998, Eriksson confirmed the generation of new neurons in the hippocampus, particularly in the granule cell layer of the adult human dentate gyrus [

9]. Two primary regions have been recognized for neurogenesis: the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles, which contains the highest concentration of actively dividing cells, and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus. Neurogenesis comprises four stages: proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival [

10]. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) differentiate into neuroblasts and glial cells, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [

11]. Immature neurons, or neuroblasts, migrate to the granule cell layer and differentiate into hippocampal neurons. Although a large number of neurons are generated, only a small fraction survive, as most newly formed cells undergo apoptosis at each neurogenesis stage. Progenitor cells exhibit limited capacity for proliferation and differentiation [

12].

In the adult human brain, the dentate gyrus (DG) and the subventricular zone (SVZ) are recognized as key sites of adult neurogenesis. This process encompasses the proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells, along with the migration and maturation of newly formed neurons. Newly generated neurons migrate from the SVZ to the olfactory bulb (OB). The fate of these newborn neurons in the DG is strictly determined by their spatial orientation, and they typically do not migrate toward the neocortex. Instead, they mainly contribute to the continuous addition of granule cells within the dentate gyrus. In the DG, three types of transcriptionally active cells have been identified: neural stem cells (NSCs, type-I cells), glial-like progenitor cells without processes (type-II cells), and neuroblasts. Similarly, in the SVZ, three transcriptionally active cell types have been distinguished: GFAP-positive neural stem cells (type-B1 cells), progenitor cells (type-C cells), and neuroblasts (type-A cells). Markers indicating the early phases of adult neurogenesis include DCX (a microtubule-associated protein involved in neuronal migration) and NeuN (a neuronal nuclear antigen), which label migrating neuroblasts and immature neurons, as well as GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein), which marks astrocytic stem cells. Phosphorylated histone H3 at Ser-10 (p-Histone H3Ser-10) provides a more specific marker, as its expression is limited to newborn neurons (neuronal progenitor cells, NPCs). Phosphorylation at the N-terminal domain of histone H3 at Ser-10 and/or Ser-28 destabilizes chromatin, facilitating replication and transcription [

13].

Numerous factors influence neurogenesis, both intrinsic and extrinsic. Key modifiers include environmental influences, growth factors, and neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate [

14]. GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, plays a role in the depolarization of progenitor cells and immature neurons during neurogenesis. Glutamate, along with dopamine and serotonin, promotes proliferation in the SGZ and SVZ regions by acting on specific receptors [

15]. Important growth factors include epidermal growth factor (EGF), which stimulates cell division and the differentiation of stem cells into neurons and astrocytes; fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which directs the differentiation of new cells [

16]; and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which enhances the survival of newly formed cells [

17]. BDNF also contributes to mood regulation, directly linking it to the neurogenic effects of antidepressants. Administering BDNF to the dentate gyrus mimics the effects of antidepressants, as demonstrated by behavioral tests, and increases neurogenesis in the subventricular zone [

18]. Both physical activity and caloric restriction exhibit neurogenic effects via BDNF, as exercise reduces cortisol levels and enhances oxygenation, thereby increasing the number of cells generated in the dentate gyrus and extending their survival. Studies indicate that reducing caloric intake by 30-40% stimulates neurogenesis. Neuroinflammation significantly impacts adult neurogenesis, producing both harmful and beneficial effects that can either enhance or inhibit the process. The outcome largely hinges on the activation state and duration of response by microglia, macrophages, and/or astrocytes [

19]. The balance between the positive and negative effects of neuroinflammation profoundly influences the efficiency of brain repair, which is critical in neurodegenerative diseases [

20]. Microglia, serving as the primary immune defense against pathogens and environmental insults, exert dual effects on adult neurogenesis, leading to pro- or anti-neurogenic outcomes. Gliosis is a common feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD) as part of the inflammatory response. Activated astrocytes and microglia are often found in abundance near neurons and amyloid plaques, and AD-affected brains show heightened expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines that are rarely present in healthy brains [

21]. The prevailing hypothesis suggests a chronic inflammatory response to the accumulation of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. While the initial inflammatory response may offer benefits, prolonged activation of astrocytes and microglia has been shown to induce necrosis in neighboring neurons by releasing reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, proteolytic enzymes, complement factors, or excitatory amino acids [

22]. Since neuroinflammation is a significant hallmark of AD and notably influences adult neurogenesis, modulating the inflammatory environment may improve deficits directly associated with the disease and stimulate the brain's intrinsic repair mechanisms. Understanding the role of adult neurogenesis in AD is particularly critical, given that one of the primary neurogenic zones is the hippocampus, a structure essential for cognitive functions and learning, which is severely impacted in AD patients.

Exploring the relationship between the formation of new neurons and their elimination in Alzheimer's disease will provide valuable insights into the neurodegenerative process. Our study aimed to identify neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) and conduct a quantitative analysis of neurogenesis cell density, comparing patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease to a control group.

2. Materials and Methods

The research material was obtained from the Brain Bank at the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in Warsaw, Poland, and included the hippocampal dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. All brain samples were preserved in buffered 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. The study group comprised brain samples from 15 patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease (8 men, 7 women, mean age 77.85 ± 10.311 years). The control group consisted of brain samples from 15 patients (9 men, 6 women, mean age 74 ± 10.95 years) who had no significant neuropathological lesions and whose deaths were sudden (within less than 10 minutes) and without dementia. The paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut into 5 µm sections and stained with hematoxylin. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed using the following antibodies: Phospho-Histone H3Ser10 (Proteintech, 66863-1-IG, 1:2200, Rosemont, IL, USA), Leukocyte Common Antigen (LCA) (Dako, 8B11-PD7/26, 1:75, Los Angeles, CA, USA), Neuronal Nuclei (NeuN) (Millipore, MAB377, 1:100, Darmstadt, Germany), and Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) (Bio-Rad, MCA 9733, G-1, 1:700, Hercules, CA, USA). This thorough staining and analysis method allowed for a detailed examination of cellular and molecular changes in the brain samples.

Neuronal progenitor cells were counted in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles. This counting was performed using CellSens software (Tokyo, Japan). The data were then analyzed statistically using STATISTICA 12 software (TIBCO Software Inc., Poland).

3. Results

We examined the experimental material for neuropathological changes linked to Alzheimer's disease. Our studies identified the presence of GFAP-positive neural stem cells in both the control group and the group of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, specifically within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (DG) (

Figure 1) and the subventricular zone (SVZ) (

Figure 2). In these regions, the GFAP-positive stem cells had oval nuclei and irregular cytoplasm, nearly devoid of processes.

We observed a positive immunohistochemical response in the transcriptionally active nuclei of neuronal progenitor cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) (

Figure 3) and the subventricular zone (SVZ) (

Figure 4) in both experimental groups. In the Alzheimer's disease group, there was a noticeable decrease in the density of neuronal progenitor cells in both the DG and SVZ. Additionally, we detected newborn, maturing neurons labeled with NeuN in both groups (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Although the maturing neurons were not quantified, an analysis of selected cases showed a reduced density of newborn neurons in the DG of Alzheimer's patients.

To understand the mechanism behind the decreased density of neuronal progenitor cells, we performed LCA antibody labeling. Active, ramified microglia were observed in the DG (

Figure 7) and SVZ (

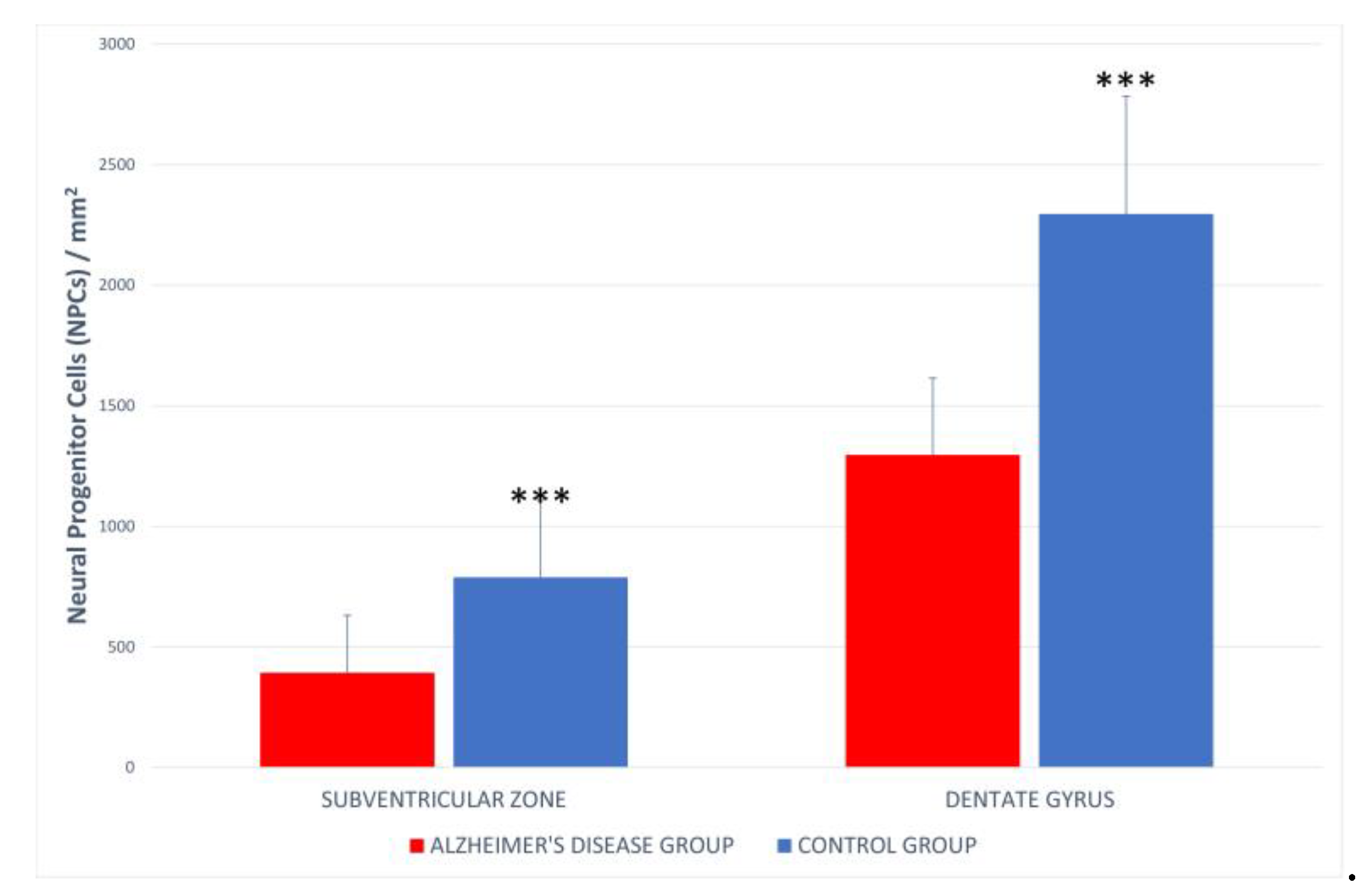

Figure 8) exclusively in the Alzheimer's disease group. Quantitative analysis of neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) expressing p-H3Ser-10 in the SVZ (393.33 ± 237.26 NPCs/mm²) and DG (1296.62 ± 319.62 NPCs/mm²) showed a reduced density in the Alzheimer's group compared to the control group (DG 2193.5 ± 488.5 NPCs/mm²; SVZ 746.8 ± 318.5 NPCs/mm²) (

Figure 9). Statistical analysis indicated significant differences between the Alzheimer's disease group and the control group.

4. Discussion

Alzheimer's disease is currently the most prevalent cause of dementia among older adults. Worldwide, it is estimated that 27 million people are affected [

23], with projections suggesting this number will triple by 2050 due to increasing life expectancy [

24]. AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that impacts brain regions responsible for memory and cognitive functions, leading to severe deficits in memory, learning, reasoning, communication, and daily activities.

Our research demonstrates a statistically significant reduction in the density of neural progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles in patients with Alzheimer's disease. This reduction correlates with disease progression. As AD advances, brain functions progressively decline, which allows for the identification of five stages of β-amyloid distribution within brain structures. Cognitive, psychiatric, and neurological disturbances emerge, with short-term memory impairment and learning difficulties being among the earliest symptoms. Given the hippocampus's critical role in these functions, significant changes in this brain region are expected. The average age of patients with Alzheimer's disease was 77.85 ± 10.311 years, reflecting variability in the severity of neurodegenerative changes within the group.

The distribution of β-amyloid plaques in the brain follows a specific pattern, classified into five distinct phases. Pathological forms of β-amyloid are neurotoxic, damaging glutamatergic neurons in the hippocampus and cortex. These dysfunctional neurons release excessive amounts of glutamate, whose toxic metabolites lead to cell death. Accumulating β-amyloid deposits, both intracellular and extracellular, may destabilize microtubules, resulting in reduced neurogenesis levels [

25]. Under normal physiological conditions, glutamate stimulates neurogenesis. Early-stage neurodegenerative changes in Alzheimer's disease may initially enhance neurogenesis as a compensatory mechanism, offsetting the loss of neurons through increased synaptogenesis.

However, neuroinflammation, which influences both the enhancement and inhibition of adult neurogenesis, can exacerbate the condition through the activation of microglia, macrophages, and astrocytes. The balance between these effects profoundly impacts the efficiency of brain repair, which is crucial in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. Neuroinflammation has been shown to affect adult neurogenesis with both detrimental and beneficial consequences, influencing its enhancement or inhibition. The final outcome depends largely on the activation state and duration of inflammation involving microglia, macrophages, and astrocytes [

20]. The balance between these effects profoundly impacts the efficiency of brain repair, which is crucial in the context of neurodegenerative disorders.

Microglia, as the primary immune cells of the brain, play a dual role in adult neurogenesis, resulting in either pro-neurogenic or antineurogenic effects. An important study by Sierra and colleagues highlighted that resting microglia regulate the balance of newborn neurons in the hippocampus through their phagocytic activity. Out of the thousands of new cells generated in the dentate gyrus, only a fraction differentiate into mature neurons, with at least half undergoing apoptosis within days to weeks of their formation. Sierra et al. demonstrated that microglia are responsible for phagocytosing these apoptotic cells and that this process does not require microglial activation [

26]. Recent findings suggest that microglia are not only crucial for adult neurogenesis but their functions are also regulated by neuronal progenitor cells. Secreted factors from NPCs can modulate microglia activation, proliferation, and phagocytosis. This interaction continues throughout the lifespan of neurons, as adult neurons regulate microglia activation through the expression of neuroimmunoregulatory proteins. Further evidence of the neurogenic effects of unchallenged microglia comes from Walton and colleagues, who found that microglia release factors that support neuroblast survival and guide neuronal differentiation in vitro [

21]. However, not only resting microglia contribute positively to adult neurogenesis. Activated microglia can also be beneficial under certain conditions, particularly through the release of antiinflammatory. It is important to note that cytokines traditionally considered pro-inflammatory can also foster a supportive environment for neurorepair [

27].

While neuroinflammation serves as a necessary physiological response to maintain brain homeostasis, it can become detrimental if chronic. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines that negatively impact neurogenesis. Cytokines can hinder the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells. Eotaxin-1, a chemokine involved in allergic responses, has recently been associated with adult neurogenesis and aging. Systemic administration of eotaxin to young mice impairs neurogenesis, resulting in learning and memory deficits. It also affects the number and size of neurospheres formed from primary NPCs, indicating that precursor cells likely have receptors for this cytokine [

28]. Gliosis, a common feature of AD, involves the activation of astrocytes and microglia near neurons and plaques. AD brains exhibit elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are rarely found in normal brains. Chronic inflammation is hypothesized to result from the accumulation of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. While initial inflammation might be protective, sustained activation of astrocytes and microglia can lead to neuronal necrosis through the release of reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, proteolytic enzymes, complement factors, or excitatory amino acids [

29].

Aβ and its precursor APP are potent activators of glial cells [68]. Aβ binds to the surface of microglial cells, regulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, leading to the expression of pro-inflammatory genes and subsequent cytokine and chemokine production [

30]. Several chemokines and their receptors are upregulated in the AD brain. For example, macrophage inflammatory protein is found in reactive astrocytes near Aβ plaques. Increased levels of various cytokines have been reported in both AD brain tissue and patient blood and cerebrospinal fluid [

31]. Eotaxin, a cytokine linked to adult neurogenesis and aging, is elevated in patient serum, and its receptor CCR3 is increased in AD brains, especially in microglia. Interactions between senile plaque components and cytokines may create a feedback loop that perpetuates neuroinflammation. For instance, Aβ can enhance the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8, and astrocytes may be activated by Aβ, contributing to a pro-inflammatory environment through the release of cytokines and chemokines [

32]. In some cases, microglial activation can be beneficial, as it may reduce Aβ accumulation through phagocytosis, aiding in the clearance and degradation of aggregates. Additionally, microglia can secrete growth factors like glia-derived neurotrophic factor, which supports neuron survival [

33]. Finally, while neurons were traditionally considered passive in neuroinflammation, they seem to actively produce neuroinflammatory molecules relevant to AD. Neurons have been shown to produce IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, acting as intermediaries between neurons and glial cells.

Given that neuroinflammation is a significant hallmark of AD and markedly influences adult neurogenesis, modulating the inflammatory environment could be beneficial for improving cognitive deficits directly caused by the disease and stimulating the brain's endogenous repair mechanisms. In AD, understanding adult neurogenesis is crucial, particularly because the hippocampus, a key neurogenic zone, is significantly affected in patients [

34].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, T.S.; software, T.S.; validation, T.S., S.T., A.A. and P.F.; formal analysis, T.S., S.T, P.K, I.S, D.S. and A.A.; investigation, T.S., P.K, I.S; resources, S.T., P.K., D.S and I.S.; data curation, S.T., P.K., I.S., D.S.; writing―original draft preparation, T.S.; writing―review and editing, A.A., P.F. and T.W.-B.; visualization T.S.; supervision, T.W.-B.; project administration, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology statutory fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002 Jul 19;297(5580):353-6. DOI: 10.1126/science.1072994.

- Carter J, Lippa CF. Beta-amyloid, neuronal death and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Mol Med. 2001 Dec;1(6):733-7. Review. DOI: 10.2174/1566524013363177.

- Schlett K. Glutamate as a modulator of embryonic and adult neurogenesis. Curr. Top. Med. Chem., 2006; 6: 949-960. DOI: 10.2174/1566524013363177.

- Uchida N, Kiuchi Y, Miyamoto K, Uchida J, Tobe T, Tomita M, Shioda S, Nakai Y, Koide R, Oguchi K. Glutamate-stimulated proliferation of rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 1998; 343: 265-273. DOI: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01526-4.

- Veena J, Rao BS, Srikumar BN. Regulation of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus by stress, acetylcholine and dopamine. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med., 2011; 2: 26-37. DOI: 10.4103/0976-9668.82312.

- Cummings JL. Drug therapy: Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004; 351: 56–67. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra040223.

- Lopez-Toledano MA, Shelanski ML. Neurogenic effect of beta-amyloid peptide in the development of neural stem cells. J. Neurosci., 2004, 24, 5439–5444. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0974-04.2004.

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Farinas I, Choi-Lundberg D, Ho WH, Castillo PE, Shinsky N, Verdugo JM, Armanini M, Ryan A, Hynes M, Phillips H, Sulzer D, Rosenthal A. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron, (2000), 25, 239–252. DOI: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7.

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998 Nov;4(11):1313-7. DOI: 10.1038/3305.

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011 May 26;70(4):687-702. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001.

- Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov O, Davies K, Scheffler B, Thomas LB, O'Brien TF, Kusakabe M, Steindler DA. Multipotent stem/progenitor cells with similar properties arise from two neurogenic regions of adult human brain. Exp Neurol. 1999 Apr;156(2):333-44. DOI: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7028.

- Seaberg RM, van der Kooy D. Adult rodent neurogenic regions: the ventricular subependyma contains neural stem cells, but the dentate gyrus contains restricted progenitors. J Neurosci. 2002 Mar 1;22(5):1784-93. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01784.2002.

- Gleeson, J.G.; Lin, P.T.; Flanagan, L.A.; Walsh, C.A. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron 1999, 23, 257–271. DOI: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3.

- Berg DA, Belnoue L, Song H, Simon A: Neurotransmitter–mediated control of neurogenesis in the adult vertebrate brain. Development, 2013; 140: 2548-2561. DOI: 10.1242/dev.088005.

- Banasr M, Hery M, Printemps R, Daszuta A. Serotonin-induced increases in adult cell proliferation and neurogenesis are mediated through different and common 5-HT receptor subtypes in the dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2004; 29: 450-460. DOI: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300320.

- Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH. Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. J. Neurosci., 1997; 17: 5820-5829. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05820.1997.

- Jin K, Zhu Y, Sun Y, Mao XO, Xie L, Greenberg DA. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2002; 99: 11946-11950. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.182296499.

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell, 2008; 132: 645-660. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033.

- Streit WJ, Walter SA, Pennell NA. Reactive microgliosis. Progress in Neurobiology. 1999;57(6):563–581. DOI: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00069-0.

- Russo I, Barlati S, Bosetti F. Effects of neuroinflammation on the regenerative capacity of brain stem cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2011;116(6):947–956. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07168.x.

- Mosher KI, Andres RH, Fukuhara T, Bieri G, Hasegawa-Moriyama M, He Y, Guzman R, Wyss-Coray T. Neural progenitor cells regulate microglia functions and activity. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:1485–1487. DOI: 10.1038/nn.3233.

- Loffler J, Huber G. β-Amyloid precursor protein isoforms in various rat brain regions and during brain development. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59(4):1316–1324. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08443.x.

- Wimo A, Jonsson L, Winblad B. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and direct costs of dementia in 2003. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2006;21(3):175–181. DOI: 10.1159/000090733.

- Hebert LE, Wilson RS, Gilley DW, Beckett L A, Scherr P A, Bennett D A, Evans D A. Decline of language among women and men with alzheimer’s disease. Journals of Gerontology Series B. 2000;55(6):P354–P360. DOI: 10.1093/aje/153.2.132.

- Chiara Scopa, Francesco Marrocco, Valentina Latina, Federica Ruggeri, Valerio Corvaglia, Federico La Regina, Martine Ammassari-Teule, Silvia Middei, Giuseppina Amadoro, Giovanni Meli, Raffaella Scardigli, Antonino Cattaneo. Impaired Adult Neurogenesis Is an Early Event in Alzheimer's Disease Neurodegeneration, Mediated by Intracellular Aβ Oligomers. Cell Death Differ 2019 Oct 7. DOI: 10.1038/s41418-019-0409-3.

- Sierra A, Encinas JM, Deudero JJP, et al. Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(4):483–495. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.014.

- Mueller FJ, McKercher SR, Imitola J, et al. At the interface of the immune system and the nervous system: how neuroinflammation modulates the fate of neural progenitors in vivo. Ernst Schering Research Foundation workshop. 2005;(53):83–114. DOI: 10.1007/3-540-27626-2_6.

- Sun, B., Halabisky, B., Zhou, Y., Palop, J.J., Yu, G., Mucke, L. & Gan, L. (2009) Imbalance between GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission impairs adult neurogenesis in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Stem Cell, 5, 624–633. DOI: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-85.

- Halliday G, Robinson SR, Shepherd C, Kril J. Alzheimer’s disease and inflammation: a review of cellular and therapeutic mechanisms. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2000;27(1-2):1–8. DOI: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03200.x.

- Ho GJ, Drego R, Hakimian E, Masliah E. Mechanisms of cell signaling and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Drug Targets. 2005;4(2):247–256. DOI: 10.2174/1568010053586237.

- Xia MQ, Hyman BT. Chemokines/chemokine receptors in the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of NeuroVirology. 1999;5(1):32–41. DOI: 10.3109/13550289909029743.

- Dewitt DA, Perry G, Cohen M, Doller C, Silver J. Astrocytes regulate microglial phagocytosis of senile plaque cores of Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental Neurology. 1998;149(2):329–340. DOI: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6738.

- Liu B, Hong JS. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;304(1):1–7. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048.

- Lee YJ, Han SB, Nam SY, Oh KW, Hong JT. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2010;33(10):1539–1556. DOI: 10.1007/s12272-010-1006-7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).