Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

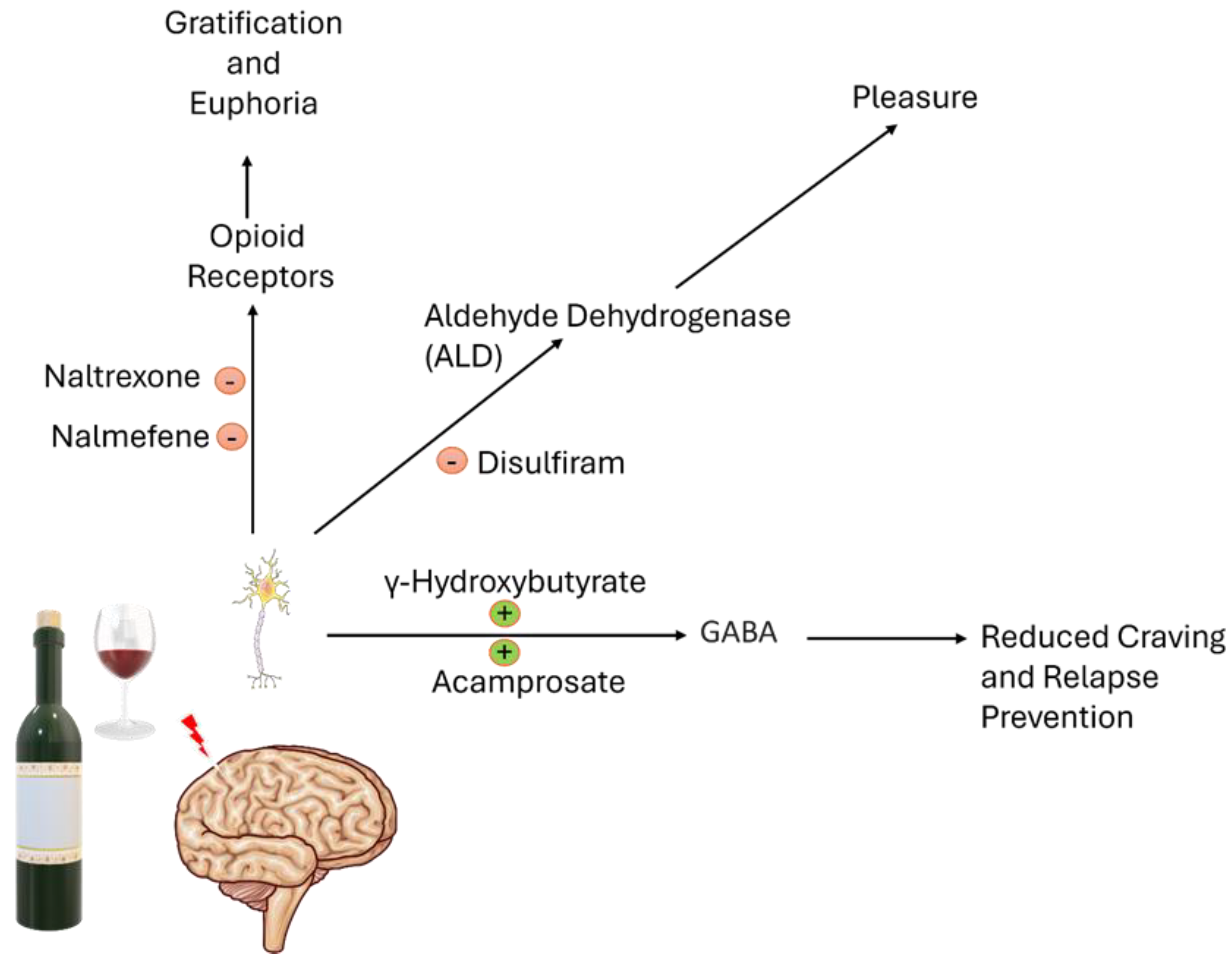

2. Pharmacotherapies and Anti-Craving Therapy for AUD

2.1. Naltrexone

2.2. Acamprosate

2.3. Disulfiram

2.4. Nalmefene

2.5. Sodium Oxybate

3. The Off-Label Therapy

3.1. Baclofen

3.2. Topiramate

3.3. Gabapentin

3.4. Ondansetron

3.5. Cytisine

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUD | Alcohol Use Disorder |

| ADHs | Alcohol Dehydrogenases |

| ALDHs | Aldehyde Dehydrogenases |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric Acid |

| KA-Rs | Kainate Receptors |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| LHBs | Lateral Habenula |

| CIN | Cholinergic Interneurons |

| NAcSh | Nucleus Accumbens |

| MOR | Mu-Opioid Receptor |

| VTA | Ventral Tegmental Area |

| CTQ | Clinical Theorist’s Questionnaire |

| KOR | Kappa-Opioid Receptor |

| DOR | Delta-Opioid Receptor |

| GHB | γ-Hydroxybutyrate |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

References

- The Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Alcohol and Drug Use in 195 Countries and Territories, 1990-2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.H.; Moore, A.A.; Sherman, S.; Keyes, K.M.; Palamar, J.J. Demographic Trends of Binge Alcohol Use and Alcohol Use Disorders among Older Adults in the United States, 2005-2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 170, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Zatonksi, W.; Taylor, B.; Anderson, P. Epidemiology and Alcohol Policy in Europe. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2011, 106 Suppl 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Ortega-Ortega, M.; Sharp, L.; Lunet, N.; Soerjomataram, I. The Cost of Premature Death from Cancer Attributable to Alcohol: Productivity Losses in Europe in 2018. Cancer Epidemiol. 2023, 84, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matejcic, M.; Gunter, M.J.; Ferrari, P. Alcohol Metabolism and Oesophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.-J.; Abdelmegeed, M.A.; Cho, Y.-E.; Akbar, M.; Rhim, J.S.; Song, M.-K.; Hardwick, J.P. Contributing Roles of CYP2E1 and Other Cytochrome P450 Isoforms in Alcohol-Related Tissue Injury and Carcinogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1164, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracina, S.; Caronti, B.; Lucarelli, M.; Francati, S.; Piccioni, M.G.; Tarani, L.; Ceccanti, M.; Caserta, M.; Verdone, L.; Venditti, S.; et al. Alcohol Consumption and Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraguti, G.; Terracina, S.; Petrella, C.; Greco, A.; Minni, A.; Lucarelli, M.; Agostinelli, E.; Ralli, M.; de Vincentiis, M.; Raponi, G.; et al. Alcohol and Head and Neck Cancer: Updates on the Role of Oxidative Stress, Genetic, Epigenetics, Oral Microbiota, Antioxidants, and Alkylating Agents. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2022, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasowski, M.D.; Harrison, N.L. The Actions of Ether, Alcohol and Alkane General Anaesthetics on GABAA and Glycine Receptors and the Effects of TM2 and TM3 Mutations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 129, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M.; Ariwodola, O.J.; Weiner, J.L.; Valenzuela, C.F. Alcohol Potently Inhibits the Kainate Receptor-Dependent Excitatory Drive of Hippocampal Interneurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 6813–6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Long, B.; Koyfman, A. The Emergency Medicine Management of Severe Alcohol Withdrawal. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 35, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloy, P.; Rutz, D.; Bhambri, A. Alcohol Withdrawal. J. Educ. Teach. Emerg. Med. 2025, 10, O1–O30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zuo, W.; Wu, W.; Zuo, Q.K.; Fu, R.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Ndukwe, M.; Ye, J.-H. Activation of Glycine Receptors in the Lateral Habenula Rescues Anxiety- and Depression-like Behaviors Associated with Alcohol Withdrawal and Reduces Alcohol Intake in Rats. Neuropharmacology 2019, 157, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuckit, M.A. Recognition and Management of Withdrawal Delirium (Delirium Tremens). N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2109–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Chischolm, A.; Parikh, M.; Thakkar, M. Cholinergic Interneurons in the Shell Region of the Nucleus Accumbens Regulate Binge Alcohol Consumption: A Chemogenetic and Genetic Lesion Study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 48, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of Addiction: A Neurocircuitry Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianoulakis, C. Endogenous Opioids and Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs of Abuse. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanagel, R. Alcoholism: A Systems Approach from Molecular Physiology to Addictive Behavior. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 649–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.M.; Jones, S.A.; Carlson, B.; Kliamovich, D.; Dehoney, J.; Simpson, B.L.; Dominguez-Savage, K.A.; Hernandez, K.O.; Lopez, D.A.; Baker, F.C.; et al. Associations between Mesolimbic Connectivity, and Alcohol Use from Adolescence to Adulthood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2024, 70, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinotti, G.; Di Nicola, M.; Tedeschi, D.; Callea, A.; Di Giannantonio, M.; Janiri, L. ; Craving Study Group Craving Typology Questionnaire (CTQ): A Scale for Alcohol Craving in Normal Controls and Alcoholics. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, R.; van den Brink, W.; Geerlings, P. A Three-Pathway Psychobiological Model of Craving for Alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. Oxf. Oxfs. 1999, 34, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilig, M.; Egli, M.; Crabbe, J.C.; Becker, H.C. Acute Withdrawal, Protracted Abstinence and Negative Affect in Alcoholism: Are They Linked? Addict. Biol. 2010, 15, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Neural Systems of Reinforcement for Drug Addiction: From Actions to Habits to Compulsion. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPheeters, M.; O’Connor, E.A.; Riley, S.; Kennedy, S.M.; Voisin, C.; Kuznacic, K.; Coffey, C.P.; Edlund, M.D.; Bobashev, G.; Jonas, D.E. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2023, 330, 1653–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.W. Anticraving Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Clinical Review. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2018, 38, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicka, M.; Tracy, D.K. Naltrexone Efficacy in Treating Alcohol-Use Disorder in Individuals with Comorbid Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 7, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, K. de O.; Ribeiro, L.; Oliveira, C.M.A. de; Carvalho, J.F.; Martins, F.T. New Solvates of the Drug Naltrexone: Protonation, Conformation and Interplay of Synthons. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M. Molecular Basis of Inhibitory Mechanism of Naltrexone and Its Metabolites through Structural and Energetic Analyses. Mol. Basel Switz. 2022, 27, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, M.; Ferrari, A.; Vitale, G.; Stefani, M.; Trenti, T.; Loria, P.; Carubbi, F.; Carulli, N.; Sternieri, E. Effect of Liver Cirrhosis on the Systemic Availability of Naltrexone in Humans. J. Hepatol. 1997, 27, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Bertolotti, M.; Dell’Utri, A.; Avico, U.; Sternieri, E. Serum Time Course of Naltrexone and 6 Beta-Naltrexol Levels during Long-Term Treatment in Drug Addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998, 52, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, R.F.; Drobes, D.J.; Voronin, K.; Durazo-Avizu, R.; Moak, D. Naltrexone Effects on Alcohol Consumption in a Clinical Laboratory Paradigm: Temporal Effects of Drinking. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2004, 173, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, K.C.; Teesson, M.; Reid, S.C.; Sannibale, C.; Thomson, C.; Phung, N.; Weltman, M.; Bell, J.R.; Richardson, K.; Haber, P.S. Naltrexone versus Acamprosate in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Multi-Centre, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2006, 101, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zornoza, T.; Cano, M.J.; Polache, A.; Granero, L. Pharmacology of Acamprosate: An Overview. CNS Drug Rev. 2003, 9, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösner, S.; Hackl-Herrwerth, A.; Leucht, S.; Lehert, P.; Vecchi, S.; Soyka, M. Acamprosate for Alcohol Dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD004332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saivin, S.; Hulot, T.; Chabac, S.; Potgieter, A.; Durbin, P.; Houin, G. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Acamprosate. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998, 35, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, M.I.; Wagstaff, A.J. Acamprosate. A Review of Its Pharmacology and Clinical Potential in the Management of Alcohol Dependence after Detoxification. Drugs 1997, 53, 1038–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus, V.I.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Bukstein, O.; Eyler, A.E.; Hilty, D.M.; Horvitz-Lennon, M.; Mahoney, J.; Pasic, J.; Weaver, M.; Wills, C.D.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, J.; Biniaz-Harris, N.; Kuvaldina, M.; Jain, S.; Lewis, K.; Fallon, B.A. Disulfiram: Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Antibiot. Basel Switz. 2023, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.D.; Lahmek, P.; Pham, H.; Aubin, H.-J. Disulfiram Efficacy in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Meta-Analysis. PloS One 2014, 9, e87366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, R.M. Drug Therapy for Alcohol Dependence. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Moore, R.D. Disulfiram Treatment of Alcoholism. Am. J. Med. 1990, 88, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schallenberg, M.; Vogel-Blaschka, D.; Spreer, M.; Göstl, J.; Petzold, J.; Pilhatsch, M. Effectiveness of Disulfiram as Adjunct to Addiction-Focused Treatment for Persons With Severe Alcohol Use Disorder. Addict. Biol. 2025, 30, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.R. Supervised Disulfiram Should Be Considered First-Line Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder. J. Addict. Med. 2024, 18, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, E.M.; Nieto, S.J.; Grodin, E.N.; Meredith, L.R.; Hurley, B.; Miotto, K.; Gillis, A.J.; Ray, L.A. Novel Agents for the Pharmacological Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder. Drugs 2022, 82, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyka, M.; Lieb, M. Recent Developments in Pharmacotherapy of Alcoholism. Pharmacopsychiatry 2015, 48, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papich, M.G.; Narayan, R.J. Naloxone and Nalmefene Absorption Delivered by Hollow Microneedles Compared to Intramuscular Injection. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelch, D.R.; Mick, I.; McGonigle, J.; Ramos, A.C.; Flechais, R.S.A.; Bolstridge, M.; Rabiner, E.; Wall, M.B.; Newbould, R.D.; Steiniger-Brach, B.; et al. Nalmefene Reduces Reward Anticipation in Alcohol Dependence: An Experimental Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, M.; Rösner, S. Nalmefene for Treatment of Alcohol Dependence. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2010, 19, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, D.; Black, J. Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate/Sodium Oxybate: Neurobiology, and Impact on Sleep and Wakefulness. CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 993–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, L.A.; Okerholm, R.A.; Lai, A.; Scharf, M.B. The Pharmacokinetics of Sodium Oxybate Oral Solution Following Acute and Chronic Administration to Narcoleptic Patients. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 44, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, W.; Addolorato, G.; Aubin, H.-J.; Benyamina, A.; Caputo, F.; Dematteis, M.; Gual, A.; Lesch, O.-M.; Mann, K.; Maremmani, I.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Sodium Oxybate in Alcohol-Dependent Patients with a Very High Drinking Risk Level. Addict. Biol. 2018, 23, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busardò, F.P.; Kyriakou, C.; Napoletano, S.; Marinelli, E.; Zaami, S. Clinical Applications of Sodium Oxybate (GHB): From Narcolepsy to Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 4654–4663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keating, G.M. Sodium Oxybate: A Review of Its Use in Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome and in the Maintenance of Abstinence in Alcohol Dependence. Clin. Drug Investig. 2014, 34, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.; Moeller, A.; Schmidt, M.; Turner, S.C.; Nimmrich, V.; Ma, J.; Rueter, L.E.; van der Kam, E.; Zhang, M. Anticonvulsant Effects of Structurally Diverse GABA(B) Positive Allosteric Modulators in the DBA/2J Audiogenic Seizure Test: Comparison to Baclofen and Utility as a Pharmacodynamic Screening Model. Neuropharmacology 2016, 101, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, J. More Treatments on Deck for Alcohol Use Disorder. JAMA 2017, 317, 2267–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Kriel, R.L.; Cloyd, J.C.; Coles, L.D.; Scherkenbach, L.A.; Tobin, M.H.; Krach, L.E. A Pilot Study Assessing Pharmacokinetics and Tolerability of Oral and Intravenous Baclofen in Healthy Adult Volunteers. J. Child Neurol. 2015, 30, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.K.; Jones, A. Baclofen: Its Effectiveness in Reducing Harmful Drinking, Craving, and Negative Mood. A Meta-Analysis. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2018, 113, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, J.L.; Leung, J.G.; Gagliardi, J.P.; Rivelli, S.K.; Muzyk, A.J. Clinical Effectiveness of Baclofen for the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Review. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2013, 5, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addolorato, G.; Caputo, F.; Capristo, E.; Colombo, G.; Gessa, G.L.; Gasbarrini, G. Ability of Baclofen in Reducing Alcohol Craving and Intake: II--Preliminary Clinical Evidence. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zaraei, S.-O.; Abduelkarem, A.R.; Anbar, H.S.; Kobeissi, S.; Mohammad, M.; Ossama, A.; El-Gamal, M.I. Sulfamates in Drug Design and Discovery: Pre-Clinical and Clinical Investigations. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 179, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, R.B.; Finno, K.E.; Tallarida, C.S.; Rawls, S.M. Topiramate-Antagonism of L-Glutamate-Induced Paroxysms in Planarians. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 649, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialer, M.; Doose, D.R.; Murthy, B.; Curtin, C.; Wang, S.-S.; Twyman, R.E.; Schwabe, S. Pharmacokinetic Interactions of Topiramate. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Yang, R.-K.; Golier, J.A.; Tischler, L.; Liong, B.; Decker, K. Effect of Topiramate on Glucocorticoid Receptor Mediated Action. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004, 29, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, J.W.; Sombati, S.; DeLorenzo, R.J.; Coulter, D.A. Cellular Actions of Topiramate: Blockade of Kainate-Evoked Inward Currents in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Epilepsia 2000, 41, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.A.; Ait-Daoud, N.; Akhtar, F.Z.; Ma, J.Z. Oral Topiramate Reduces the Consequences of Drinking and Improves the Quality of Life of Alcohol-Dependent Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Rosenthal, N.; Capece, J.A.; Wiegand, F.; Mao, L.; Beyers, K.; McKay, A.; Ait-Daoud, N.; Anton, R.F.; Ciraulo, D.A.; et al. Topiramate for Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2007, 298, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampman, K.M.; Pettinati, H.M.; Lynch, K.G.; Spratt, K.; Wierzbicki, M.R.; O’Brien, C.P. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Topiramate for the Treatment of Comorbid Cocaine and Alcohol Dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 133, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zour, E.; Lodhi, S.A.; Nesbitt, R.U.; Silbering, S.B.; Chaturvedi, P.R. Stability Studies of Gabapentin in Aqueous Solutions. Pharm. Res. 1992, 9, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearingen, D.; Aronoff, G.M.; Ciric, S.; Lal, R. Pharmacokinetics of Immediate Release, Extended Release, and Gastric Retentive Gabapentin Formulations in Healthy Adults. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 56, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.P.; Gee, N.S.; Su, T.Z.; Kocsis, J.D.; Welty, D.F.; Brown, J.P.; Dooley, D.J.; Boden, P.; Singh, L. A Summary of Mechanistic Hypotheses of Gabapentin Pharmacology. Epilepsy Res. 1998, 29, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furieri, F.A.; Nakamura-Palacios, E.M. Gabapentin Reduces Alcohol Consumption and Craving: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, J.J.; Pavlicova, M.; Choi, C.J.; Brooks, D.J.; Mahony, A.L.; Kosoff, Z.; Naqvi, N.; Brezing, C.; Luo, S.X.; Levin, F.R. An Open-Label Pilot Study of Pregabalin Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2021, 47, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.H.; Ponnudurai, R.; Schaefer, R. Ondansetron: A Selective 5-HT(3) Receptor Antagonist and Its Applications in CNS-Related Disorders. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotelo, C.K.; Shropshire, S.B.; Quimby, J.; Simpson, S.; Gustafson, D.L.; Zersen, K.M. Pharmacokinetics and Anti-Nausea Effects of Intravenous Ondansetron in Hospitalized Dogs Exhibiting Clinical Signs of Nausea. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 45, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Roache, J.D.; Javors, M.A.; DiClemente, C.C.; Cloninger, C.R.; Prihoda, T.J.; Bordnick, P.S.; Ait-Daoud, N.; Hensler, J. Ondansetron for Reduction of Drinking among Biologically Predisposed Alcoholic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2000, 284, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzler, H.R.; Pierucci-Lagha, A.; Feinn, R.; Hernandez-Avila, C. Effects of Ondansetron in Early- versus Late-Onset Alcoholics: A Prospective, Open-Label Study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 27, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens, M.; Fonseca, F.; Mateu, G.; Farré, M. Efficacy of Antidepressants in Substance Use Disorders with and without Comorbid Depression. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005, 78, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotti, C.; Clementi, F. Cytisine and Cytisine Derivatives. More than Smoking Cessation Aids. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Newcombe, D.; Sheridan, J.; Tingle, M. Pharmacokinetics of Cytisine, an A4 Β2 Nicotinic Receptor Partial Agonist, in Healthy Smokers Following a Single Dose. Drug Test. Anal. 2015, 7, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, J.-F.; Lukas, R.J.; Benowitz, N.L.; West, R.; Dresler, C.M. Cytisine for Smoking Cessation: A Research Agenda. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 92, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Signaling | Clinical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone | Antagonist of MOR, DOR, KOR opioid receptors | Reduces craving and heavy drinking, superior in high-relapse profiles |

| Acamprosate | Unclear; likely modulates NMDA receptors and GABA analog | Supports abstinence, especially in moderate to severe AUD |

| Disulfiram | Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor; aversive agent | Maintains abstinence via psychological deterrent |

| Nalmefene | MOR/DOR antagonist, KOR partial agonist | Reduces alcohol use and binge drinking, effective |

| Sodium Oxybate | GABAB agonist, acts also on extrasynaptic GABAA | Effective in withdrawal and abstinence maintenance, mimics alcohol effects |

| Drug | Signaling | Clinical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Baclofen | Selective GABAB receptor agonist | Improves abstinence, not effective for craving or heavy drinking |

| Topiramate | Modulates GABA and glutamate (NMDA/kainate) receptors | Reduces withdrawal symptoms, limited effect on abstinence |

| Gabapentin | Increases GABA levels | Reduces craving and withdrawal symptoms |

| Pregabalin | Binds α2δ subunit of Ca²⁺ channels | Reduces craving, effective and better absorption than gabapentin |

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 receptor antagonist | Reduces drinking in AUD with comorbid MDD |

| Cytisine | Partial agonist of α4β2 nAChRs, modulates dopamine reward system | Reduces alcohol self-administration in smokers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).