Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 37A35; 62M10; 60G07

1. Introduction

1.1. Contents of the Paper

1.2. Permutations as Patterns in Time Series

1.3. Pattern Frequencies in Time Series

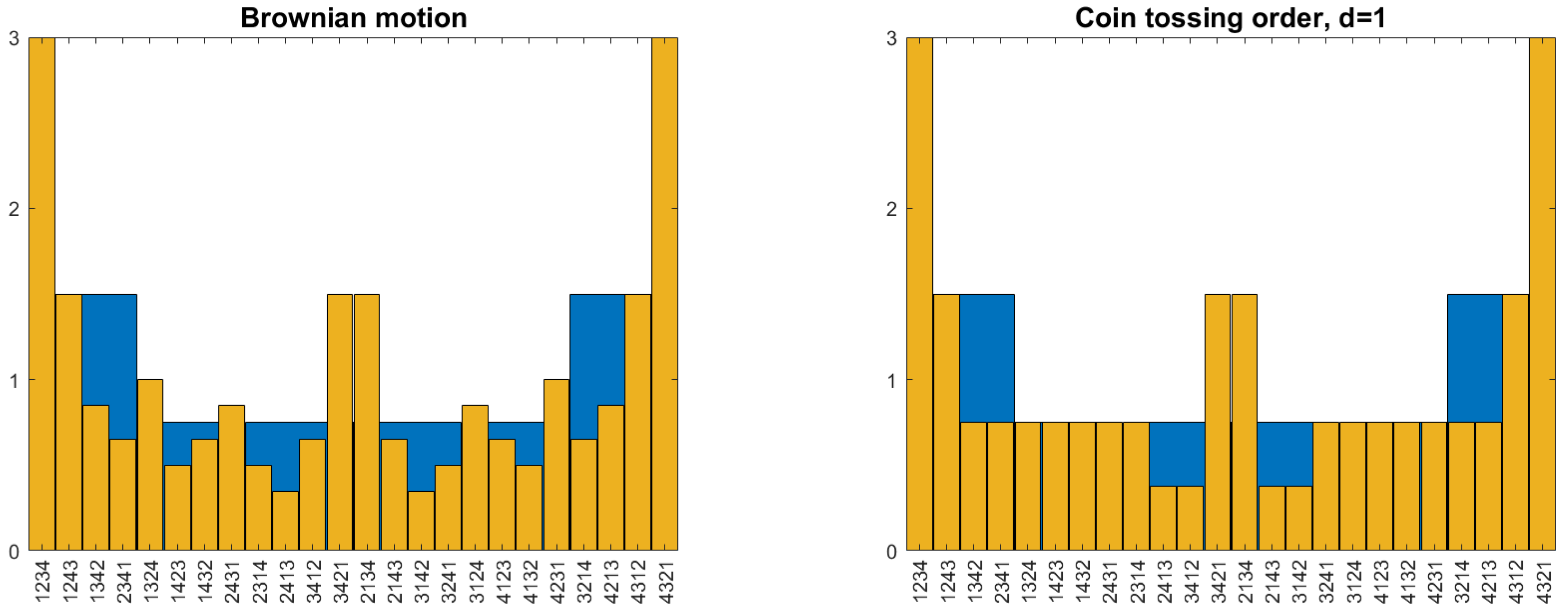

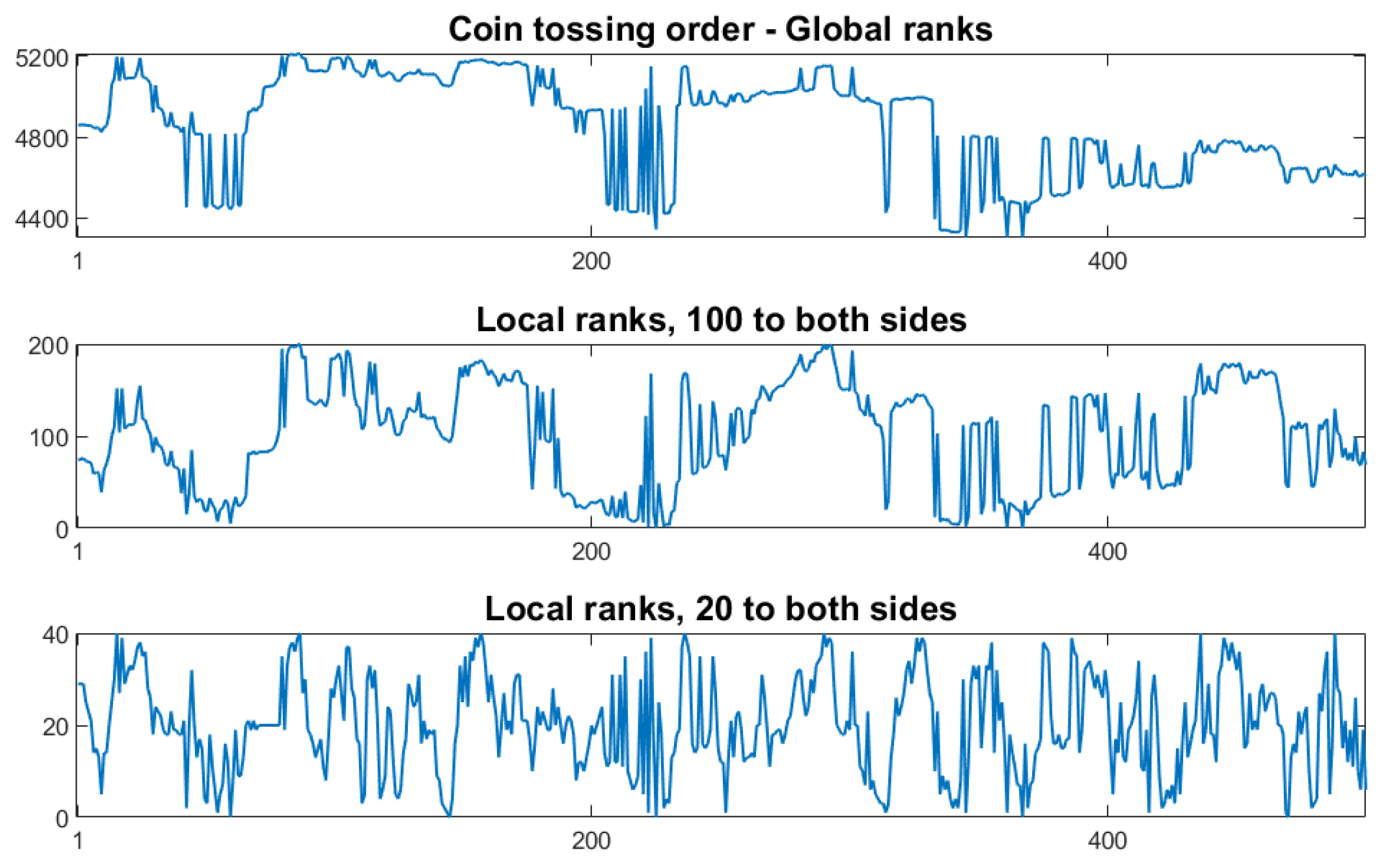

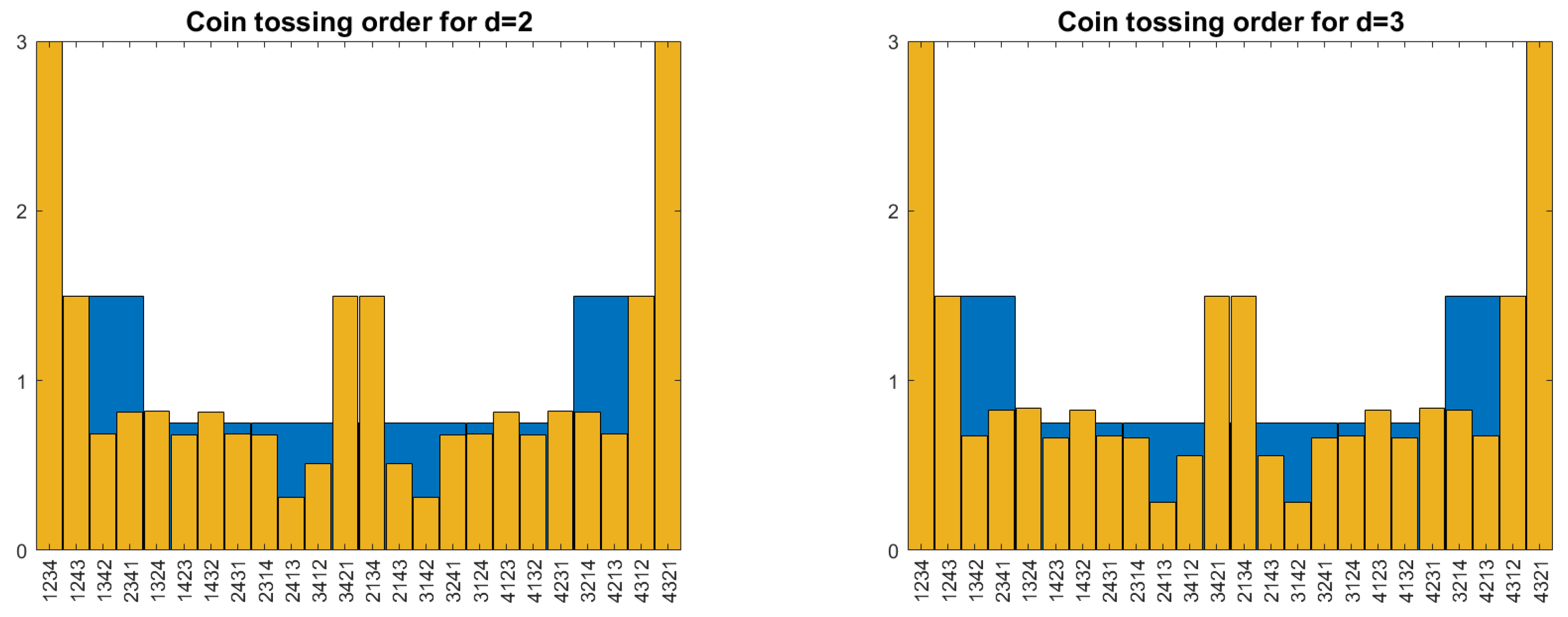

1.4. Visualization of Pattern Frequencies by an Ordinal Histogram

1.5. Stationary and Order Stationary Processes

1.6. The topic of this paper.

1.7. Symmetry and Independence Properties of Ordinal Processes

2. The Coin-Tossing Order—An Ordinal Process Without Values

2.1. Ranking Fighters by Their Strength

2.2. Definition of the Coin Tossing Order

2.3. Basic Properties of the Coin Tossing Order

- (i)

- The coin tossing order is stationary and has the ordinal Markov property.

- (ii)

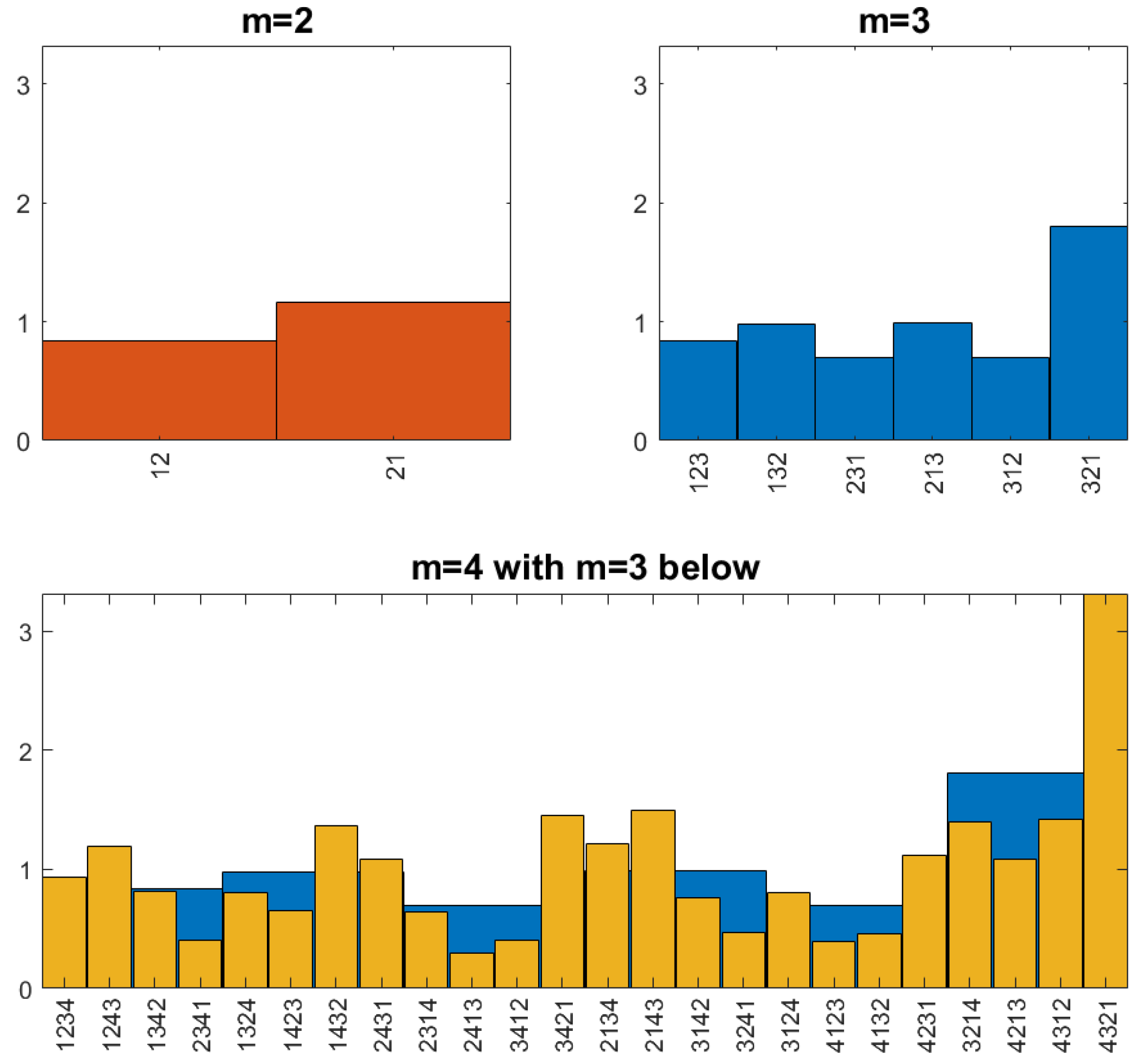

- For any permutation π of length the pattern probability is with

- (iii)

- The pattern probabilities are invariant under time reversal and reversal of the values.

- (iv)

- For we have and for the other permutations of length 3.

2.4. Computer Work and Breakdown of Self-Similarity

3. Rudiments of a Theory of Ordinal Processes

3.1. Random Stationary Order

3.2. The Problem to Find Good Models

- Independence: Markov property or k-dependence of patterns (cf. [12]).

- Self-similarity: should not depend on For processes with short-term memory, like Figure 1, this could be replaced by the requirement that the converge to the uniform distribution, exponentially with increasing There must be a law connecting the for different Otherwise, how can we describe them all?

- Smoothness: There should not be too much zigzag in the time series. Patterns like 3142 should be exceptions. This can perhaps be reached by minimizing certain energy functions.

3.3. Random Order on

- (i)

- A sequence of permutations defines an order on if for the pattern is represented by the first m values of the pattern

- (ii)

- A sequence of probability measures on defines a random order P on if for for and holds

- (iii)

- The random order P defined by the is stationary if and only if for for and holds

3.4. The Space of Random Orders

3.5. Extension of Pattern Distributions

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandt, C. Statistics and contrasts of order patterns in univariate time series. Chaos 2023, 33, 033124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Sinn, M. Ordinal analysis of time series. Physica A 2005, 356, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Sinn, M.; Edmonds, J. Time Series from the ordinal viewpoint. Stochastics and Dynamics 2007, 7, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo, J.M. Permutation complexity in dynamical systems; Springer Seires in Synergetics, Springer: Berlin, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amigo, J.; Keller, K.; Kurths, J. Recent progress in symbolic dynamics and permutation complexity. Ten years of permutation entropy. Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 2013, 222, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zanin, M.; Zunino, L.; Rosso, O.; Papo, D. Permutation entropy and its main biomedical and econophysics applications: a review. Entropy 2012, 14, 1553–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levya, I.; Martinez, J.; Masoller, C.; Rosso, O.; Zanin, M. 20 years of ordinal patterns: perspectives and challenges. Europhysics Letters 2022, 138, 31001, arXiv2204.12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmett, G. ; Stirzaker., D. Probability and random processes, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sinn, M.; Keller, K. Estimation of ordinal pattern probabilities in Gaussian processes with stationary increments. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 2011, 55, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, A.; Dehling, H. Testing for structural breaks via ordinal pattern dependence. J. Amer. Stat. Assoc. 2017, 112, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betken, A.; Buchsteiner, J.; Dehling, H.; Münker, I.; Schnurr, A.; Woerner, J.H. Ordinal patterns in long-range dependent time series. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 2021, 48, 969–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, A.R.; Hlinka, J. Assessing serial dependence in ordinal patterns processes using chi-squared tests with application to EEG data analysis. Chaos 2022, 32, 073126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, C. Non-parametric tests for serial dependence in time series based on asymptotic implementations of ordinal-pattern statistics. Chaos 2022, 32, 093107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüßgen, I.; Schnurr, A. Ordinal pattern dependence in the context of long-range dependence. Entropy 2021, 23, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betken, A.; Wendler, M. Rank-based change-point analysis for long-range dependent time series. Bernoulli 2022, 28, 2209–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, F. Ordinal language of antipersistent binary walks. Physics Letters A 2024, 527, 130017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C.; Shiha, F. Order patterns in time series. J. Time Series Analysis 2007, 28, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsinger, H. Independence tests based on symbolic dynamics. Working paper No. 150, Österreichische Nationalbank.

- DeFord, D.; Moore, K. Random Walk Null Models for Time Series Data. Entropy 2017, 19, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, C.; Martin, M.R.; Keller, K.; Matilla-Garcia, M. Non-parametric analysis of serial dependence in time series using ordinal patterns. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 2022, 168, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, C.; Schnurr, A. Generalized ordinal patterns in discrete-valued time series: nonparametric testing for serial dependence. Journal of Nonparametric Statistics 2024, 36, 573–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C. Order patterns, their variation and change points in financial time series and Brownian motion. Statistical Papers 2020, 61, 1565–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrechts, P.; Maejima, M. Selfsimilar Processes; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bandt, C.; Pompe, B. Permutation entropy: a natural complexity measure for time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 88, 174102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, G. Equilibrium states in ergodic theory; Vol. 42, London Math. Soc. Student Texts, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Pitman, J.; Tang, W. Regenerative random permutations of integers. Annals Prob. 2019, 47, 1378–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).