1. Introduction

Corrosion has been identified as a major challenge in industry due to the harsh environmental conditions that prevail in the region. Acidic corrosion is the most common in industrial fields, such as oil and gas, chemical processing, and metal manufacturing. In 2022, for example, it accounted for 32.4% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP. However, corrosion remains a costly challenge, with global losses estimated at

$2.5 trillion annually, or 3.4% of the world’s GDP, according to NACE International [

1]. In the U.S. oil and gas industry alone, corrosion costs approximately

$1.4 billion annually in exploration and production, with additional expenses of

$7 billion for monitoring, maintenance, and replacement in gas and liquid transmission pipelines [

1,

2].

Developing effective corrosion inhibitors is fundamental to minimizing these major economic losses. Organic compounds with heteroatoms such as oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur, together with π-electron systems, represent the main components of conventional corrosion inhibitors, which improve their adsorption onto metal surfaces to boost protective performance [

3,

4]. However, the environmental toxicity associated with many traditional inhibitors has necessitated a paradigm shift toward sustainable alternatives that maintain high inhibition efficiency while minimizing ecological impact

Recent research has directed attention toward the potential repurposing of pharmaceutical substances as green corrosion inhibitors, particularly those containing N-heterocyclic structures. These compounds demonstrate strong potential to replace traditional inhibitors because they can easily decompose in the environment while showing reduced toxicity and cost-effectiveness [

5].

The inherent molecular architecture of pharmaceuticals contains multiple heteroatoms, aromatic rings, and functional groups that allow these substances to create protective films on metals through adsorption reactions and metal ion complexation [

6,

7]. This structural versatility allows them to provide comprehensive protection against various corrosion manifestations, including uniform, pitting, and crevice corrosion [

7].

Olanzapine, a typical antipsychotic medication widely prescribed for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, represents a promising candidate for repurposing as a corrosion inhibitor. As a selective antagonist of 5HT2A/D2 receptors, olanzapine has received FDA authorization for multiple psychiatric applications and is listed among the World Health Organization's essential medicines [

8]. The number of annual U.S. prescriptions for olanzapine exceeds 3 million, which positions the medication among the most commonly prescribed drugs [

9,

10]. The two-year shelf life of olanzapine results in large amounts of expired medication that must be disposed of while also creating opportunities to find sustainable uses for the waste.

The molecular structure of olanzapine features multiple nitrogen atoms within heterocyclic rings, aromatic systems with delocalized π-electrons, and functional groups capable of interacting with metal surfaces—characteristics that align with established criteria for effective corrosion inhibitors. Furthermore, the possibility of synthesizing derivatives with enhanced inhibition properties through strategic molecular modifications offers additional avenues for optimizing performance while maintaining environmental compatibility. The convergence of increasing industrial demand for corrosion inhibitors, growing environmental concerns regarding conventional inhibitors, and the global imperative for sustainable resource utilization underscores the significance of investigating pharmaceutical compounds as potential green corrosion inhibitors. This research direction not only addresses critical industrial challenges but also contributes to circular economic principles by transforming pharmaceutical waste into valuable industrial resources.

The present study aims to comprehensively investigate the corrosion inhibition efficacy of olanzapine and two novel synthesized derivatives on C1018 carbon steel in 1M HCl solution. The research methodology encompasses advanced electrochemical techniques, immersion tests, thermodynamic calculations, and surface characterization using FT-IR spectroscopy and SEM/EDX analysis to elucidate the inhibition mechanisms and quantify protective performance. By establishing structure-activity relationships and optimizing inhibition parameters, this work seeks to develop environmentally benign corrosion inhibitors derived from pharmaceutical compounds, thereby addressing both industrial corrosion challenges and environmental sustainability imperatives.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of the Corrosion Inhibitors

D-1 (OLZ 1) and D-2 (OLZ 2) were synthesized in neat conditions and under microwave irradiation (Scheme 1). The compounds were synthesized through the reaction of Olanzapine with acrylamide and ethyl chloroacetate to give D-1 and D-2, respectively, and were recrystallized from acetone. Microwave irradiations were conducted in an Anton Paar Monowave 300 single-mode microwave in 30 mL Pyrex [

11,

12]. The progress of the reactions was monitored using Merck silica gel 60F-254 thin-layer plates. The compounds were characterized using 1HNMR and FTIR. The 1HNMR spectra were recorded at 500 MHz (Bruker), and IR spectra were recorded on an FTIR (02) spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Bruker). The 1HNMR and IR spectra are presented in

supplementary materials (Figures S1 and S2) [

13].

2.2. Weight Loss Measurements

The weight loss or immersion test is one of the primary tests used to estimate the inhibition efficiency of a substance. The sample was prepared, weighed, and then immersed in 250 ml of the solution in a jar with a lid, in the absence and presence of the optimum concentration for each inhibitor (300 ppm), for 24 hours. After that, C1018 coupons are taken out and treated by (pickling) to remove oxide contaminants formed on the surface in atmospheric oxygen when the metal is exposed to air [

14]. After that, the corrosion rate is calculated [

15,

16].

Where: w: the coupon weight loss in grams, A: the coupon surface area in cm

2, T: the immersion period in 24 h, D: the coupon density in g/cm

3, CR˚ corrosion rate of solution without inhibitor and CR

i corrosion rate of solution with inhibitor.

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

The electrochemical evaluation was carried out using a standard three-electrode corrosion cell consisting of carbon steel (C1018) as working electrode, silver/silver chloride electrode (Ag/AgCl) as the reference electrode and graphite rod as the counter electrode. The electrodes were immersed in 300 ml of 1M HCl solution. Gamry reference 3000 potentiostat/ galvanostat/ ZRA (Gamry Instrument, USA) was used to perform all the electrochemical measurements. Before testing, the working electrode was immersed in the test solution for 1 hour to achieve a stable open circuit potential (OCP). All electrochemical experiments were performed in static, aerated solutions at room temperature. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), linear polarization resistance (LPR), and potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) tests were conducted to assess the corrosion behavior of carbon steel with and without inhibitors. EIS measurements were conducted over a frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 mHz with an AC amplitude of ±10 mV versus OCP. This was followed with LPR tests using a potential scan of ±10 mV relative to the OCP at a rate of 0.125 mV/s. Lastly, PDP tests were carried out by scanning the system at 0.5 mV/s from –250 mV in the cathodic direction to 250 mV in the anodic direction relative to the OCP. The Gamry Echem Analyst 7.9.0 software package was used for data analysis, fitting, and simulations.

2.4. Computational Methods

The DFT calculations for the four olanzapine molecules were performed using the Dmol

3 module –

Biovia Material Studio [

17]. The GAA/BLYP functional combined with the DNP basis set was employed in the calculations. The COSMO method was applied to simulate the solvent effect of water [

18]. The convergence tolerance were set to fine. Based on the frontier orbital theory, the electronic parameters in terms of the highest occupied molecular orbital (

EHOMO), energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (

ELUMO), energy gap (

ΔE), electron affinity (

A), ionization potential (

I), electronegativity (

χ), global hardness (

η), and the fraction of electron transfer (

ΔN) were calculated according to Eq. (4) – Eq. (9):

where χ

Fe and η

Fe represent the absolute electronegativity and hardness of iron, which have the theoretical values of 0 and 7 eV/mol, respectively [

19].

2.4.1. MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted to obtain the interaction energy between the Fe surface and the inhibitor molecules. The Fe(110) crystallographic surface was selected for its stability and abundance of active sites [

20]. A supercell of the surface scaled to 10 × 10 times its original size was created and optimized. The interaction models comprised three layers: Fe (110), solvent with the molecule, and a 30 Å vacuum. The solvent layer was designed to simulate 1 M HCl and included 491 H

2O, 9 Cl

−, 9 H

3O

+, and 1 inhibitor molecule. All MD simulations were performed using the Forcite module and the COMPASS forcefield. The models underwent dynamic runs under the NVT ensemble at 298 K, controlled by the Andersen thermostat. The simulation time was 500 ps with a 1 fs time step. Interaction energy was then calculated based on Eq. (10).

where:

is the total energy of the entire system;

is the energy of the surface with the solution; and

is the energy of the inhibitor molecule only. The negative magnitude of interaction energy gives the values of binding energy (

), as expressed in Eq. (11).

Several simulation models were constructed to study the diffusion of corrosive particles across the inhibitor films. These models include a blank model containing 180 H

2O, 5 Cl

−, and 5 H

3O

+, as well as inhibited models with 10 molecules. The built models were optimized using the COMPASS forcefield. Subsequently, dynamics runs were performed (i.e., equilibrium and production runs) under the NVT ensemble at room temperature (298 K). The conformations generated from the MD simulations were used to track the corrosive particles (H

2O, Cl

−, and H

3O

+) using the mean square displacement (MSD), as expressed in Eq. (12). The diffusion coefficients (

D) of the species were then calculated by fitting the MSD-time curves according to Einstein’s law of diffusion (Eq. (13)) [

21,

22].

where:

is the MSD at time

t;

represent the total number of particles; while

and

denote the position of a particle

at time

and at the initial time, respectively.

2.5. Surface Analyses

2.5.1. FTIR Analysis

FTIR is a spectroscopic technique, which can provide critical information on the interactions between inhibitor molecules and the substrate by detecting changes in vibrational frequencies of chemical bonds. These information is helpful in understanding corrosion inhibition mechanism [

23]. A small amount of the powder sample was placed directly onto the ATR crystal, without the need for KBr. Gentle pressure were applied to ensure optimal contact between the sample and the crystal. The Shimadzu - IRAFFINITY-2 instrument was used for the FTIR analysis.

2.5.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the C1018 carbon steel surface exposed to uninhibited and inhibited 1 M hydrochloric acid was analyzed using the scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray analyzer (VEGA 3 TESCAN coupled with AMETEK EDX) operated at 20 kV with a 10 mm working distance. SEM can provide information on the morphology and the type of corrosion on the metal surface while EDX is used for elemental analysis [

24].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Weight Loss Measurements

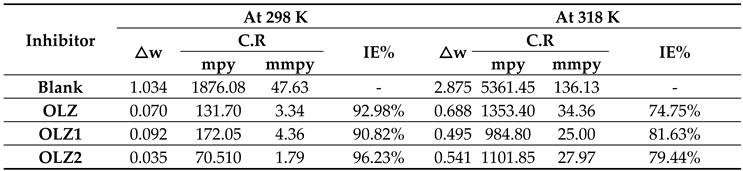

Weight loss measurement was conducted to evaluate the performance of the corrosion inhibitors at 298 K and 318 K.

Table 1 and Figure 1 present the inhibition efficiency values for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2 at these two temperatures. At 298 K, the inhibition efficiencies were 92.98%, 90.82%, and 96.23% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively, indicating a stronger interaction of the inhibitor molecules at lower temperature[

25,

26]. However, at the elevated temperature of 318 K, the inhibition efficiencies decreased to 74.75%, 81.63%, and 79.44% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. The decrease in inhibition efficiency with increasing temperature suggests the desorption of the inhibitor molecules from the metal surface. Interestingly, OLZ1 exhibited the smallest decrease in inhibition efficiency with temperature, suggesting that the acrylamide group enhances the thermal stability of the adsorbed inhibitor film. This could be attributed to stronger interactions between the acrylamide group and the metal surface, possibly through coordination bonds involving the amide nitrogen and oxygen atoms.

3.2. Open Circuit Potential Measurements

Figure 2 presents the OCP versus time plots for the blank solution and solutions containing 300 ppm of OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2. In the absence of inhibitors (blank), the OCP stabilized at approximately -0.47 V vs. Ag/AgCl, indicating active corrosion of the carbon steel substrate. Upon the addition of the inhibitors, a notable shift toward more positive (less negative) potential was observed. The OCP values stabilized at approximately -0.40 V, -0.42 V, and -0.44 V for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. This positive shift in OCP suggests that all three compounds predominantly affect the anodic reaction of the corrosion process [

27]. The OCP measurements also revealed that potential stabilization occurred within the first 1000 seconds of immersion for all systems, after which minimal fluctuations were observed for the remainder of the 3500-second test period. This indicates rapid formation of a protective film on the metal surface in the presence of inhibitors [

28].

3.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS analyzed corrosion inhibition on C1018 in 1M HCl solution, both with and without olanzapine and derivatives (OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2). This method reveals both the electrochemical reaction rates and the surface properties of the examined systems. Nyquist plots reveal the corrosion of steel in 1M HCl solution that consists of semicircles with their centers below the real axis [

29], as shown in Figure 3. These characteristics of charge transfer-controlled dissolution with significantly increased diameters in the presence of inhibitors indicate enhanced interfacial charge transfer resistance at the metal/electrolyte interface.

The Nyquist plots for the blank and OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 inhibited solutions presented four semi-circular capacitive arcs between high and low frequency regions; the high frequency time constant (R

f//CPE

f) represented a defective/porous protective OLZ and its derivatives film on the metal surface while the low frequency time constant (R

ct//CPE

dl) represented the double layer formation at the metal/electrolyte interface [

30,

31]. The Bode plots (Figure 4) further support these findings, showing increased impedance magnitude |Z| and phase angle shifts toward more negative values in the presence of inhibitors. The phase angle plots exhibit a single time constant, which broadens in the presence of inhibitors, indicating the formation of a more compact and protective film on the metal surface [

32,

33].

The equivalent circuit model used to fit the EIS data is presented in Figure 3 (insert). The parameters include R

s, which is the solution resistance, CPE

dl, which is constant phase elements for the double-layer, and R

ct is the charge transfer resistance. The n values (ranging from 0.867 to 0.996) are less than unity, confirming the non-ideal capacitive behavior of the metal/solution interface. Moreover, higher n values indicate greater surface heterogeneity because of inhibitor adsorption. The observed inductive effects in the EIS data are related to the complex structure of the double layer at the metal-solution interface [

34,

35]. It is a key indicator of the interface's electrical properties and inhibitor adsorption characteristics. These C

dl values were calculated from the impedance data by applying Eq. (14) in

Table 2.

The Cdl, which is double layer capacitance, Rct presents charge transfer, Y0 is the CPE coefficient (reciprocal of impedance and also known as admittance).

The reduction of electrical double layer value from 193.850 (blank) to ( 79.578, 65.471, 51.416) in the presence of OLZ and its derivatives (OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2) indicates an increase in the thickness of the electrical double layer, which retards the corrosion process as represent in

Table 2. Also, this decrease of (C

dl) at the metal/solution interface with the presence of OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 can result from a lower local dielectric constant lead to inhibitors adsorbed on the C1018 carbon steel. While quantitative analysis through non-linear least squares fitting to an equivalent electrical circuit revealed a huge increase in faradaic polarization resistance (R

p) from 140.897 Ω·cm² for the uninhibited system to 1200.97, 1430.42, and 1646.42 Ω·cm² for OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2, respectively, as shown in

Table 2. Inhibition efficiency from the EIS technique was calculated utilizing the relationship defined in Eq. (15). The experimental results consistently demonstrate that all three compounds exhibit excellent corrosion inhibition properties, with inhibition efficiencies exceeding 88% at 300 ppm. The inhibition efficiency follows the order: OLZ2 > OLZ1 > OLZ. This trend suggests that the structural modifications introduced in OLZ1 and OLZ2 enhance the corrosion inhibition properties of the parent molecule.

IE is corrosion efficiency, Rp, which is the polarization resistance. The polarization resistance values without any inhibitor present are denoted by Rp (blank), while the values with an inhibitor present are denoted by Rp (inh),

The superior performance of OLZ2 is attributed to its ethyl acetate functionality, which provides additional oxygen donor atoms for coordinating covalent bonding with d-orbitals of iron and enhanced molecular hydrophobicity. The acrylamide group in OLZ1 showed intermediate performance because of its additional electron-rich centers and π-electron interactions with the metal substrate. The consistent inhibition hierarchy across multiple electrochemical techniques validates the reliability of these findings. The research creates structure-activity relationships for olanzapine-based corrosion inhibitors and shows their effectiveness as protective agents for carbon steel in aggressive acidic environments.

3.4. Potentiodynamic Polarization Studies (PDP)

PDP measurements were conducted to further elucidate the corrosion inhibition mechanism of the studied compounds. The polarization curves for carbon steel in 1M HCl with and without 300 ppm of OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2 are shown in Figure 5. The electrochemical parameters of corrosion potential (E

corr), corrosion current density (i

corr) and inhibition efficiency (% IE) values were determined from the corresponding Tafel plots and the obtained data are shown in

Table 3. The inhibition efficiencies can be calculated from i

corr values using the following Eq.(16):

Where i

corr (blank) and i

corr (inh) are the sample's corrosion current density in 1 M HCl without and with inhibitors, respectively.

The corrosion current density (icorr) decreased significantly from 200.00 μA cm⁻² for the blank solution to 20.100, 15.900, and 14.600 μA cm⁻² for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. This reduction in icorr corresponds to inhibition efficiencies of 89.95%, 92.05%, and 92.70% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively, which is agreement with the EIS results. The corrosion potential (Ecorr) shifted from -447.00 mV for the blank solution to -401.000, -397.00, and -422.000 mV for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. All three compounds act as anodic-type inhibitors, affecting the anodic metal dissolution.

The anodic (βa) and cathodic (βc) Tafel slopes were also modified in the presence of inhibitors. The anodic Tafel slope decreased from 160.80 mV/dec for the blank to 100.00, 89.000, and 91.400 mV/dec for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. Similarly, the cathodic Tafel slope increased from 120.00 mV/dec for the blank to 132.700, 218.600, and 241.600 mV/dec for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. These changes in Tafel slopes indicate that the inhibitors modify the mechanism of both anodic dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution, with a more pronounced effect on the anodic reaction. This anodic type of inhibition behavior is further confirmed by the potentiodynamic polarization results, which show that both the anodic branches of the polarization curves are affected by the presence of inhibitors. The changes in both anodic (βa) and cathodic (βc) Tafel slopes indicate that the inhibitors modify the mechanism of both electrode reactions. The more pronounced increase in anodic Tafel slopes.

3.5. Linear Polarization Resistance (LPR)

A linear polarization resistance technique was employed to evaluate the efficiency of OLZ and its derivatives in inhibiting corrosion at 1 M HCl. This measurement enables real-time nondestructive corrosion rate evaluation as an electrochemical assessment tool that researchers commonly used to measure material corrosion rates. The ±10 mV is relative to OCP, which produces a direct relationship between corrosion current and potential values. A small polarization selection maintained an accurate measurement of corrosion rates because it avoided permanent disruption of the corrosion process [

36,

37].

Table 3 presents both polarization resistance (Rp) and efficiency values. The LPR parameters derived from the curve fitting appear in

Table 3. The E

corr values of inhibited solutions show more positive values than the blank acid solution, while the E

corr values do not follow any specific pattern when using different inhibitors. The inhibition efficiency (%IE) of the OLZ inhibitors was calculated using the following Eq. (18) [

38]:

Rp, which is the polarization resistance. The polarization resistance values without any inhibitor present are denoted by Rp (blank), while the values with an inhibitor present are denoted by Rp (inh) and icorr, which is the corrosion current density. βa is the anodic and βc cathodic Tafel slope.

The results in

Table 3 demonstrate that polarization resistance values increase after adding inhibitors compared to the acid solution without inhibitors. The addition of OLZ together with its derivatives proves effective at blocking corrosion in this extremely acidic environment, as the addition of OLZ and its derivatives produced identical patterns of decreased corrosion rates together with enhanced inhibition efficiencies. The polarization resistance (Rp) increased from 132.20 Ω for the blank solution to 1135.66 Ω, 1473.00 Ω, and 1760.66 Ω for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively. The corresponding inhibition efficiencies are 88.35%, 91.01%, and 92.47% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively, which are in excellent agreement with the values obtained from EIS and PDP.

3.6. Quantum Chemistry Calculations

This section discusses the results of the quantum chemistry-based calculations. The molecular orbitals play a crucial role in determining the electron transfer process of an organic molecule [

39,

40]. The frontier molecular orbitals of the olanzapine derivatives are shown in Figures 8 and 9. The HOMOs and LUMOs are concentrated on the OLZ-based molecules, except for the piperazine rings. These locations likely denote and accept electrons on the iron surface during the adsorption process [

41]. The reactivity parameters of OLZ and its derivatives are presented in Figures 10,11. The energy gap (ΔE) of the HOMO-LUMO spectrum for OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 were 2.778, 2.785 and 2.790 eV, respectively. A smaller gap indicates higher chemical reactivity, suggesting good inhibition efficiency [

42]. In this study, all molecules showed almost similar

ΔE values. These theoretical results matched well with the experimental findings based on the electrochemical and weight-loss measurements. The dipole moment (

μ) is another vital parameter in determining a molecule's effectiveness as a corrosion inhibitor, as it reflects bond polarity. The molecules studied exhibited dipole moments higher than water (1.88 Debye) [

43], indicating their potential to outcompete water molecules and adsorb onto the substrate at the metal-solution interface.

Fukui function based on the Mulliken analysis was performed to characterize the local reactivity of the molecules [

44]. displays the

fk– and

fk+ indices of all molecules. The highest

fk– values are localized around the nitrogen and sulfur atoms, suggesting these sites are more prone to electrophilic attack. The

fk+ values are significant in the sulfur atoms in the thiazepine ring, indicating these sites are more prone to nucleophilic attack. These heteroatoms are likely involved in the adsorption process on the steel surface, facilitating the formation of a protective layer as present in Figure 10.

3.7. Adsorption Behavior

The interaction of the molecular surface system was investigated in Figure 11 using MD simulations shows the adsorption configurations of the inhibitor molecules on the Fe (110) surface in the presence of 1 M HCl. The adsorption models revealed that the olanzapine derivative molecules were adsorbed on the substrate in a nearly parallel orientation. Although the overall geometry of olanzapine and its derivatives is non-planar due to their three-dimensional structures, their large size allows for more adsorption sites on the metal substrate. This is seen with the OLZ2 molecule, which achieved a more optimal adsorption mode than the others. The adsorption position is crucial for maximizing surface coverage and thereby enhancing the inhibition ability of the molecules [

45,

46]. Based on the generated dynamic models, the binding energy of all the molecules was calculated, as shown in these values were 173.21, 190.90, and 191.81 for OLZ-Fe (110), OLZ1-Fe(110), and OLZ2-Fe(110), respectively. OLZ2 exhibited the highest binding energy due to its adsorption configuration. These results are consistent with the DFT calculations as well as the experimental findings, which showed that OLZ2 demonstrated excellent inhibition performance in all aspects.

3.8. Diffusion Study

The diffusion models of the blank and inhibited systems are shown in (Figures 12, 13 and Table 6 In principle, the inhibition film should be able to prevent the migration of the species to the metal surface [

47,

48]. Thus, the MSD analysis was used to track the mobility of the particles in the different inhibitors’ layers, showing the double-log plots of the MSD-time curves for corrosive particles across the blank and inhibited films. The data indicated an increasing trend of MSD values over time, implying the diffusion region of the particles. In addition, the MSD curves for the inhibited systems were significantly lower than those for the blank systems, indicating that the inhibitor molecules restricted particle movement. Based on the MSD data, the diffusion coefficients of H

2O, H

3O

+, and Cl

− were calculated, as presented in. The inhibitor molecules significantly decreased the D-values of H

2O, H

3O

+, and Cl

− by around 85%, 83%, and 84%, respectively, on average. It was found that OLZ2 is most effective in reducing the diffusion of H

2O (0.35 × 10

−9 m

2․s

−1), while OLZ2 and OLZ were more effective for H

3O

+ (0.17 × 10

−9 m

2․s

−1) and Cl

− (0.07 × 10

−9 m

2․s

−1), respectively.

3.9. Surface Analysis

3.9.1. SEM-EDX Analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was used to examine the surface morphology and elemental composition of the carbon steel samples before and after immersion in the test solutions [

49,

50]. The SEM images and EDX spectra are presented in Figure 6. The SEM image of the bare metal surface shows a relatively smooth morphology with some polishing marks. After immersion in 1M HCl (blank solution), the surface appears severely corroded with numerous pits and cracks, indicating aggressive attack by the acidic medium. In contrast, the surfaces of samples immersed in inhibitor-containing solutions exhibit significantly less damage, with smoother morphologies suggesting the formation of protective films. The surface protection appears to be most effective with OLZ2, followed by OLZ1 and OLZ. The EDX analysis

Table 4 provides quantitative information on the elemental composition of the sample surfaces. The bare metal surface primarily consists of iron (Fe, 85.56%) with small amounts of carbon (C, 9.69%), oxygen (O, 1.69%), and other elements. After immersion in 1M HCl, the iron content decreases dramatically to 62.71%, while the oxygen content increases to 20.76%, indicating severe oxidation of the metal surface. In the presence of inhibitors, the iron content is largely preserved (83.90%, 84.19%, and 85.49% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively), suggesting effective protection against corrosion. Furthermore, the detection of nitrogen (N) on the inhibited surfaces (1.74%, 1.68%, and 1.68% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively) provides direct evidence for the adsorption of inhibitor molecules, as nitrogen is a key element in the molecular structure of these compounds. The carbon content is also higher on the inhibited surfaces (11.41%, 10.75%, and 10.81% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively) compared to the bare metal (9.69%), further confirming the presence of organic inhibitor molecules. The oxygen content is significantly lower on the inhibited surfaces (1.62%, 1.78%, and 2.24% for OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2, respectively) compared to the corroded surface in HCl (20.76%), indicating reduced oxidation of the metal in the presence of inhibitors.

The surface analysis techniques SEM-EDX provide direct evidence for the adsorption of inhibitor molecules on the metal surface and the formation of protective films. The SEM images clearly show the protective effect of the inhibitors, with significantly less surface damage compared to the blank solution. The smoother morphology of the inhibited surfaces suggests the formation of a uniform protective film that shields the metal from the aggressive medium. The EDX analysis confirms the presence of inhibitor molecules on the metal surface through the detection of nitrogen, which is a key element in the molecular structure of these compounds. The higher carbon content and lower oxygen content on the inhibited surfaces compared to the corroded surface in HCl further support the formation of a protective organic film that prevents oxidation of the metal.

3.9.2. FT-IR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to characterize the molecular structure of the inhibitors and to identify potential functional groups involved in the adsorption process on the metal surface. The results of FTIR analysis of pure OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2 are presented in Figure 7. The spectra reveal characteristic absorption bands corresponding to various functional groups present in the inhibitor molecules. All three compounds exhibit bands in the region of 3200-3500 cm ¹ attributed to N-H⁻ stretching vibrations, bands around 2900-3000 cm ¹ due to C-H stretching, and bands in the region⁻ of 1600-1700 cm ¹ assigned to C=O stretching vibrations. The spectra of OLZ1 and OLZ2 show⁻ additional bands compared to the parent OLZ, confirming the successful incorporation of acrylamide and ethyl acetate groups, respectively. The blank solution showed a peak at 3300 cm-1 that was due to O-H stretching, but it was absent in the presence of the inhibitors. The -OH, -C=N, C=C and aromatic ring on the surface of the metal serve as active sites for the interaction of the inhibitors.

3.10. Inhibition Mechanism

The analysis of corrosion inhibition depends on how inhibitors adsorb onto steel surfaces. Organic compounds adsorb to surfaces through physical or chemical methods, but both mechanisms can happen at the same time. The adsorption process depends on three main factors, which include inhibitor charge, molecular structure and metal surface properties. The inhibitor adsorption process relies on functional groups such as aromatic ring and( N-H, C=O, C=C and C-O) and N present in OLZ and its derivatives, which act as adsorption centers. The electron transfer capability of these functional groups to metal d-orbitals plays a crucial role in the adsorption process [

51].

FTIR spectral data deliver essential information about how the studied compounds inhibit the corrosion process, as shown in Figure 7 and

Table 7. It is clear from Figure 7 that the inhibited samples show diminished O-H stretching bands at 3300 cm

-1, which indicate that inhibitor molecules move water molecules off the metal surface to block their involvement in corrosion reactions. This displacement is a crucial step in the inhibition process, as water molecules are essential for the electrochemical reactions that drive corrosion.

Table 5.

Quantum chemical indices of the molecules.

Table 5.

Quantum chemical indices of the molecules.

| Parameters |

Inhibitor molecules |

|

| OLZ |

OLZ1 |

OLZ2 |

| EHOMO (eV) |

−4.643 |

−4.637 |

−4.669 |

| ELUMO (eV) |

−1.865 |

−1.852 |

−1.879 |

| I (eV) |

4.643 |

4.637 |

4.669 |

| A (eV) |

1.865 |

1.852 |

1.879 |

| ΔE (eV) |

2.778 |

2.785 |

2.790 |

| χ (eV) |

3.254 |

3.245 |

3.274 |

| η (eV) |

1.389 |

1.393 |

1.395 |

| ΔN (eV) |

−2.697 |

−2.697 |

−2.671 |

| μ (Debye) |

4.603 |

6.510 |

5.160 |

Table 6.

Diffusion coefficient of corrosive particles in films.

Table 6.

Diffusion coefficient of corrosive particles in films.

| Inhibitor film |

D (x10⁻⁹ m²․s⁻¹) |

| H2O |

H3O+

|

Cl−

|

| Blank |

2.79 |

2.57 |

1.24 |

| OLZ |

0.39 |

0.35 |

0.07 |

| OLZ1 |

0.66 |

0.87 |

0.25 |

| OLZ2 |

0.35 |

0.17 |

0.19 |

Table 7.

FTIR band assignments for corrosion products and inhibitor effects.

Table 7.

FTIR band assignments for corrosion products and inhibitor effects.

| NO. |

Band |

Absorbance Peak |

Reason |

| 1 |

Fe-O |

450 |

The presence of a sharp, intense peak indicates the formation of ferrous and ferric oxides or hydroxides |

| 2 |

O-H |

3300 |

The presence of a hydroxyl group is an indication of the formation of ferric oxides or hydroxides |

| 3 |

C-Cl |

1000 |

Presence of chloride ions as corrosion products |

| 4 |

Fe-O |

490 |

Reduction in peak intensity due to the presence of the inhibitor |

| 5 |

C-Cl |

1000 |

Reduction in peak intensity due to the presence of the inhibitor |

| 6 |

O-H |

3300 |

Disappearance of the hydroxyl group in the presence of the inhibitor |

The decreased intensity of Fe-O peaks at 490 cm-1 in the presence of inhibitors proves that inhibitors block the formation of iron oxides, which act as primary corrosion products. Inhibitor molecules adsorb on metal surface active sites to block both anodic and cathodic reactions that occur during corrosion. By impeding these electrochemical reactions, the inhibitors effectively reduce the corrosion rate.

FTIR spectra of corrosion products show that inhibitor-specific peaks persist, which demonstrates that inhibitors maintain their adsorption to metal surfaces throughout the testing duration. Multiple adsorption mechanisms operate based on the various functional groups found in inhibitor molecules [

52,

53]. The proposed mechanism in OLZ is shown in Figure 7, where the immersion of steel coupons in the blank HCl resulted in metal dissolution, whereas the addition of OLZ resulted in inhibitor adsorption on the steel surface through chemisorption and physisorption. The adsorption process receives additional support from electrostatic forces between charged inhibitor molecules and metal surfaces, especially in acidic conditions where the metal surface develops a positive charge and inhibitor molecules become protonated. This type of interaction corresponds to physisorption and is generally weaker than chemisorption, but can still contribute significantly to the overall inhibition effect. The spectra of OLZ1 and OLZ2 show additional bands compared to the parent OLZ, confirming the successful incorporation of acrylamide and ethyl acetate groups, respectively.

4. Conclusions

The study determined the inhibition of corrosion for carbon steel in 1M HCl solution using a comprehensive suite of electrochemical and surface analytical techniques by olanzapine (OLZ) and two novel derivatives, OLZ1 and OLZ2. This study determined the following results from the experimental data obtained:

The three inhibition properties of OLZ and its derivatives on C1018 carbon steel in 1M HCl solution were very high at 300 ppm, where inhibition efficiencies exceeded 88%. However, inhibition efficiency was temperature and concentration-dependent.

Electrochemical studies indicate that the three inhibitors are predominantly anodic. PDP-derived inhibition efficiencies were in agreement with those obtained from EIS measurements.

At 298 K, the inhibition efficiency followed the order OLZ2> OLZ1> OLZ, while at 318 K, it followed the order OLZ1 > OLZ2 > OLZ, which confirms that the structural modifications enhanced the corrosion inhibition properties of the parent molecule.

The SEM-EDX analysis demonstrates that OLZ and its derivatives effectively inhibit steel corrosion in 1M HCl compared to the uninhibited solution.

The FTIR spectroscopy results show that the metal surface active sites include -NH, -C=N, C=C and aromatic ring structures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

References

- Jacobson, G.A. NACE international’s IMPACT study breaks new ground in corrosion management research and practice. The Bridge 2016, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Fayomi, O.; Akande, I.; Odigie, S. Economic impact of corrosion in oil sectors and prevention: an overview. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing 2019, 022037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moubaraki, A.H.; Obot, I.B. Corrosion challenges in petroleum refinery operations: Sources, mechanisms, mitigation, and future outlook. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, N. Green compounds to attenuate aluminum corrosion in HCl activation: a necessity review. Chemistry Africa 2020, 3, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baari, M.J.; Sabandar, C.W. A Review on expired drug-based corrosion inhibitors: Chemical composition, structural effects, inhibition mechanism, current challenges, and future prospects. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 21, 1316–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, R.; Vashishth, P.; Bairagi, H.; Sehrawat, R.; Shukla, S.; Mangla, B. Applicability of drugs as sustainable corrosion inhibitors. Adv Mater Lett 2023, 14, 2304–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwer, S.; Shukla, S.K. Recent advances in the applicability of drugs as corrosion inhibitor on metal surface: A review. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott, T.; Moja, L.; Huttner, B.; Okwen, P.; Raviglione, M.C.B.; Kredo, T.; Schünemann, H.J. WHO Model list of essential medicines: Visions for the future. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2024, 102, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, S.T.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Khan, Z.; Imran, L.; Syed, A.A.; Tahir, M.J.; Jassani, Z.; Singh, M.; Asghar, M.S.; Ahmed, A. Samidorphan/olanzapine combination therapy for schizophrenia: Efficacy, tolerance and adverse outcomes of regimen, evidence-based review of clinical trials. Annals of medicine and surgery 2022, 79, 104115–104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinCalc DrugStats Database. The Top 300 Drugs of 2022 in the United States by Prescription. ClinCalc LLC; 2022. 2022.

- Obermayer, D.; Glasnov, T.N.; Kappe, C.O. Microwave-assisted and continuous flow multistep synthesis of 4-(pyrazol-1-yl) carboxanilides. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2011, 76, 6657–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermayer, D.; Kappe, C.O. On the importance of simultaneous infrared/fiber-optic temperature monitoring in the microwave-assisted synthesis of ionic liquids. Organic & biomolecular chemistry 2010, 8, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, R.; Nandiyanto, A.B.D. How to read and interpret 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectrums. Indonesian Journal of Science and Technology 2021, 6, 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard, A. G31-72: Standard Practice for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing of Metals. Annual Book of ASTM Standards; ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Satapathy, A.; Gunasekaran, G.; Sahoo, S.; Amit, K.; Rodrigues, P. Corrosion inhibition by Justicia gendarussa plant extract in hydrochloric acid solution. Corrosion science 2009, 51, 2848–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testing, A.S. f.; Materials In ASTM G1-03: Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens, ASTM: 2004.

- Shankar, U.; Gogoi, R.; Sethi, S.K.; Verma, A. Introduction to materials studio software for the atomistic-scale simulations. In Forcefields for atomistic-scale simulations: materials and applications; Springer, 2022; pp. 299–299. [Google Scholar]

- Klamt, A.; Schüürmann, G. COSMO: a new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Guo, L.; Fu, A.; Xiang, T.; Jin, Y. Experimental and molecular modeling studies of multi-active tetrazole derivative bearing sulfur linker for protecting steel from corrosion. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2022, 351, 118638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.; Bahraq, A.A.; Alamri, A.H. Density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation of the corrosive particle diffusion in pyrimidine and its derivatives films. Computational Materials Science 2022, 210, 111428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, I.M.; Klafter, J. From diffusion to anomalous diffusion: a century after Einstein’s Brownian motion. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2005, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.-Q.; Guo, A.-L.; Yan, Y.-G.; Jia, X.-L.; Geng, Y.-F.; Guo, W.-Y. Computer simulation of diffusion of corrosive particle in corrosion inhibitor membrane. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2011, 964, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Spectroscopic methods for nanomaterials characterization 2017, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.; Abdullah, A. In Scanning electron microscopy (SEM): A review, Proceedings of the 2018 international conference on hydraulics and pneumatics—HERVEX, Băile Govora, Romania, 2018; pp 7-9.

- Nahlé, A.; Abu-Abdoun, I.I.; Abdel-Rahman, I. Effect of Temperature on the Corrosion Inhibition of Trans-4-Hydroxy-4′-Stilbazole on Mild Steel in HCl Solution. International Journal of corrosion 2012, 2012, 380329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.; Obi-Egbedi, N.; Umoren, S. Adsorption characteristics and corrosion inhibitive properties of clotrimazole for aluminium corrosion in hydrochloric acid. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2009, 4, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.K.; Saraswat, V.; Mitra, R.K.; Obot, I.; Yadav, M. Mitigation of corrosion in petroleum oil well/tubing steel using pyrimidines as efficient corrosion inhibitor: Experimental and theoretical investigation. Materials Today Communications 2021, 26, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chamas, M.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, H. Electrochemical behavior of jasmine tea extract as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2018, 13, 3625–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, B.; Praveen, B.; Hebbar, N.; Venkatesha, T. Anticorrosion potential of hydralazine for corrosion of mild steel in 1m hydrochloric acid solution. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 2015, 7, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguzie, E.; Li, Y.; Wang, F. Corrosion inhibition and adsorption behavior of methionine on mild steel in sulfuric acid and synergistic effect of iodide ion. Journal of colloid and interface science 2007, 310, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruna, K.; Saleh, T.A.; Quraishi, M. Expired metformin drug as green corrosion inhibitor for simulated oil/gas well acidizing environment. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2020, 315, 113716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobin, M.; Zamindar, S.; Banerjee, P. Mechanistic insight into adsorption and anti-corrosion capability of a novel surfactant-derived ionic liquid for mild steel in HCl medium. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 385, 122403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touir, R.; Errahmany, N.; Rbaa, M.; Benhiba, F.; Doubi, M.; Kafssaoui, E.E.; Lakhrissi, B. Experimental and computational chemistry investigation of the molecular structures of new synthetic quinazolinone derivatives as acid corrosion inhibitors for mild steel. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1303, 137499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.M.; Costa, A.R.; Leite, M.C.; Martins, V.; Lee, H.-S.; da CS Boechat, F.; de Souza, M.C.; Batalha, P.N.; Lgaz, H.; Ponzio, E.A. A detailed experimental performance of 4-quinolone derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acid media combined with first-principles DFT simulations of bond breaking upon adsorption. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 375, 121299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acidi, A.; Sedik, A.; Rizi, A.; Bouasla, R.; Rachedi, K.O.; Berredjem, M.; Delimi, A.; Abdennouri, A.; Ferkous, H.; Yadav, K.K. Examination of the main chemical components of essential oil of Syzygium aromaticum as a corrosion inhibitor on the mild steel in 0.5 M HCl medium. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 391, 123423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, S.; Law, D.; Bungey, J.; Cairns, J. Environmental influences on linear polarisation corrosion rate measurement in reinforced concrete. Ndt & E International 2001, 34, 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Olasunkanmi, L.O.; Obot, I.B.; Kabanda, M.M.; Ebenso, E.E. Some quinoxalin-6-yl derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in hydrochloric acid: experimental and theoretical studies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 16004–16019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A. Polypropylene glycol: A novel corrosion inhibitor for× 60 pipeline steel in 15% HCl solution. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2016, 219, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, G.; Hu, S.; Yan, Y.; Ren, Z.; Yu, L. Theoretical evaluation of corrosion inhibition performance of imidazoline compounds with different hydrophilic groups. Corrosion Science 2011, 53, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Kaya, S.; Obot, I.B.; Zheng, X.; Qiang, Y. Toward understanding the anticorrosive mechanism of some thiourea derivatives for carbon steel corrosion: A combined DFT and molecular dynamics investigation. Journal of colloid and interface science 2017, 506, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kang, Q.; Wang, Y. Theoretical study of N-thiazolyl-2-cyanoacetamide derivatives as corrosion inhibitor for aluminum in alkaline environments. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2018, 1131, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi-Egbedi, N.; Obot, I.; El-Khaiary, M.I. Quantum chemical investigation and statistical analysis of the relationship between corrosion inhibition efficiency and molecular structure of xanthene and its derivatives on mild steel in sulphuric acid. Journal of Molecular Structure 2011, 1002, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Quraishi, M.; Singh, A. 5-Substituted 1H-tetrazoles as effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2016, 10, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakki, M.; Galai, M.; Rbaa, M.; Abousalem, A.S.; Lakhrissi, B.; Rifi, E.; Cherkaoui, M. Investigation of imidazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in sulfuric acidic environment: experimental and theoretical studies. Ionics 2020, 26, 5251–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Quraishi, M.; Rhee, K.Y. Electronic effect vs. molecular size effect: experimental and computational based designing of potential corrosion inhibitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 430, 132645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, G. Influence of corrosion products on the inhibition effect of pyrimidine derivative for the corrosion of carbon steel under supercritical CO2 conditions. Corrosion Science 2020, 166, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M. Theoretical insights into the inhibition performance of three neonicotine derivatives as novel type of inhibitors on carbon steel. Journal of Renewable Materials 2020, 8, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Cao, X.; Zhang, J. Molecular dynamics simulation of corrosive species diffusion in imidazoline inhibitor films with different alkyl chain length. Corrosion science 2013, 73, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.A.A.; Abdulkareem, M.H.; Annon, I.A.; Hanoon, M.M.; Al-Kaabi, M.H.; Shaker, L.M.; Alamiery, A.A.; Isahak, W.N.R.W.; Takriff, M.S. Weight loss, thermodynamics, SEM, and electrochemical studies on N-2-methylbenzylidene-4-antipyrineamine as an inhibitor for mild steel corrosion in hydrochloric acid. Lubricants 2022, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.; Umoren, S.; Ankah, N. Pyrazine derivatives as green oil field corrosion inhibitors for steel. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 277, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, D.Q.; Hieu, T.D.; Le Minh Pham, T.; Tuan, D.; Nam, P.C.; Obot, I.B. DFT study of the interactions between thiophene-based corrosion inhibitors and an Fe 4 cluster. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2017, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, J.; Sounthari, P.; Parameswari, K.; Chitra, S. Acenaphtho [1, 2-b] quinoxaline and acenaphtho [1, 2-b] pyrazine as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acid medium. Measurement 2016, 77, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Srivastava, V.; Quraishi, M. Novel quinoline derivatives as green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium: electrochemical, SEM, AFM, and XPS studies. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2016, 216, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Weight loss data of carbon steel showing the corrosion rate and inhibition efficiency in the absence and presence of the inhibitors in 1 M HCl at 298 K and 318 K.

Table 1.

Weight loss data of carbon steel showing the corrosion rate and inhibition efficiency in the absence and presence of the inhibitors in 1 M HCl at 298 K and 318 K.

Table 2.

The data obtained from fitted EIS curves for corrosion control of carbon steel with the presence and absence of OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2 at 300 ppm.

Table 2.

The data obtained from fitted EIS curves for corrosion control of carbon steel with the presence and absence of OLZ, OLZ1, and OLZ2 at 300 ppm.

| Inh. |

Rs

Ω⋅cm2

|

CPEdl

|

|

Rct

Ω⋅cm2

|

CPEf

|

|

Rf

Ω⋅cm2

|

Cdl μF·cm⁻² |

Rp

Ω⋅cm2

|

IE

% |

| Y01 (mΩsncm−2) |

n 1

|

Y02 (mΩsncm−2) |

n 2

|

| Blank |

131.15 |

89.380 |

0.867 |

1.74 |

70.465 |

0.958 |

8.005 |

193.850 |

140.897 |

- |

| OLZ |

0.74 |

63.657 |

0.967 |

10.89 |

92.736 |

0.882 |

1189.333 |

79.578 |

1200.97 |

88.28 |

| OLZ1 |

1.64 |

47.53 |

0.972 |

1416.3 |

20.820 |

0.984 |

12.449 |

65.471 |

1430.42 |

90.15 |

| OLZ2 |

1.32 |

50.41 |

0.996 |

898.06 |

29.413 |

0.904 |

747.033 |

51.416 |

1646.42 |

91.45 |

Table 3.

Results for the inhibitory effect of OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 on carbon steel by potentiodynamic polarization and linear polarization resistance experiments.

Table 3.

Results for the inhibitory effect of OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 on carbon steel by potentiodynamic polarization and linear polarization resistance experiments.

| Inhibitor |

PDP |

LPR |

Ecorr

(mV/SCE) |

icorr

(μA cm−2) |

βa

(mV/dec) |

βc

(mV/dec) |

IE% |

Rp

|

IE% |

| Blank |

-447.00 |

200.00 |

160.80 |

120.00 |

- |

132.20 |

- |

| OLZ |

-401.000 |

20.100 |

100.00 |

132.700 |

89.95 |

1135.66 |

88.35 |

| OLZ1 |

-397.000 |

15.900 |

89.000 |

218.600 |

92.05 |

1473.00 |

91.01 |

| OLZ2 |

-422.000 |

14.600 |

91.400 |

241.600 |

92.70 |

1760.66 |

92.47 |

Table 4.

Atomic percentage of metal in the presence and absence of OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 by EDX.

Table 4.

Atomic percentage of metal in the presence and absence of OLZ, OLZ1 and OLZ2 by EDX.

| Element |

Metal |

Metal with HCl |

Metal with OLZ |

Metal with OLZ1 |

Metal with OLZ2 |

| N |

1.57 |

0.91 |

1.74 |

1.68 |

1.68 |

| O |

1.69 |

20.76 |

1.62 |

1.78 |

2.24 |

| C |

9.69 |

14.42 |

11.41 |

10.75 |

10.81 |

| S |

0.46 |

0.36 |

0.43 |

0.43 |

0.39 |

| P |

0.65 |

0.51 |

0.59 |

0.73 |

0.67 |

| Mn |

0.38 |

0.33 |

0.31 |

0.45 |

0.40 |

| Fe |

85.56 |

62.71 |

83.90 |

84.19 |

85.49 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).