Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

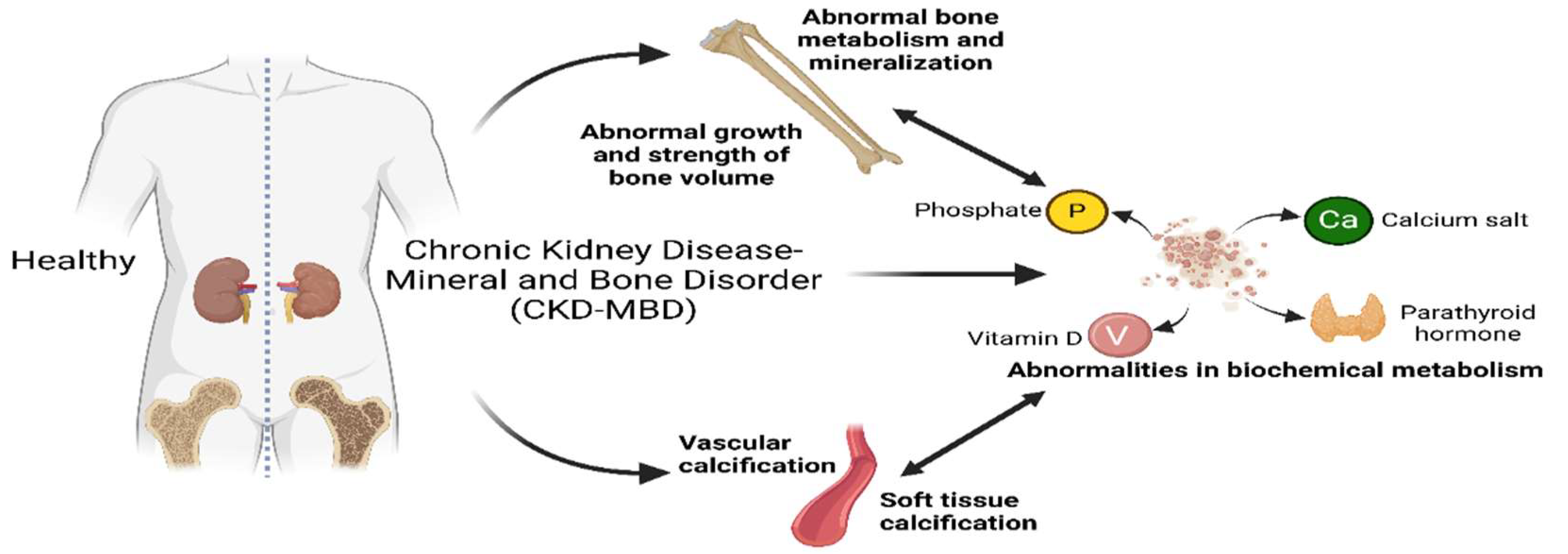

Pathophysiology

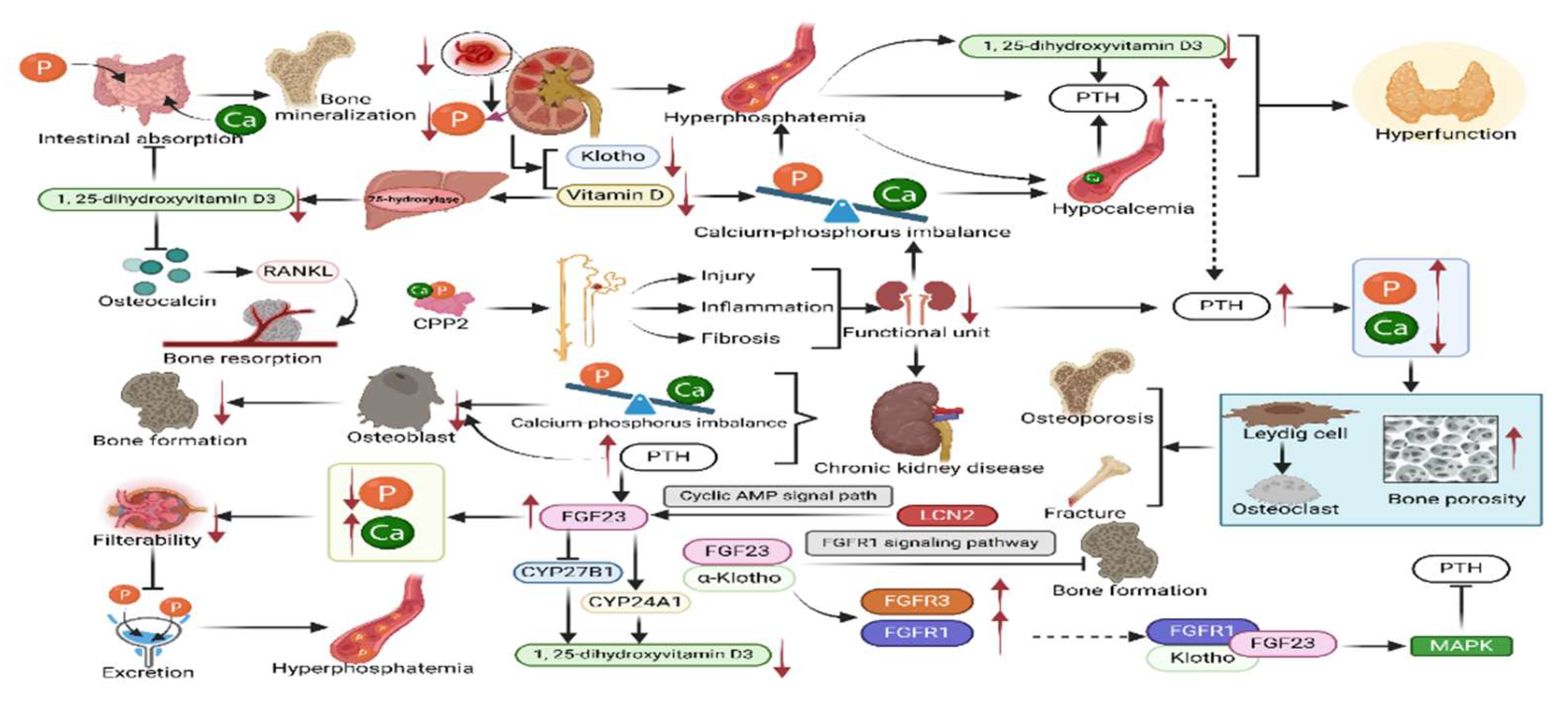

1. Abnormalities in the Metabolism of Calcium, Phosphorus, Vitamin D, Parathyroid Hormone, and FGF23

- 1.1.

- Disorders of Calcium and Phosphorus Balance

- 1.2.

- Disorders of Vitamin D Metabolism

- 1.3.

- Disorders of Parathyroid Hormone Metabolism

- 1.4.

- Disorders of FGF23-Klotho Metabolism

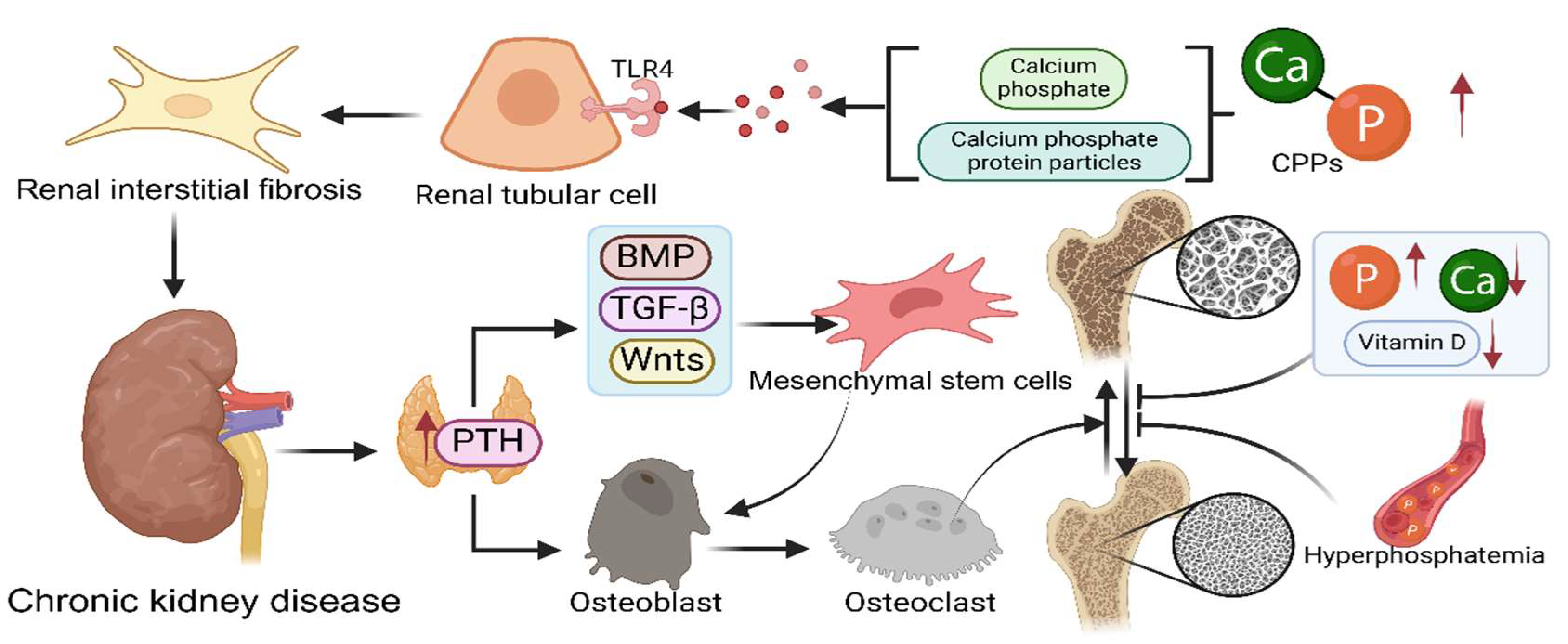

2. Skeletal Changes

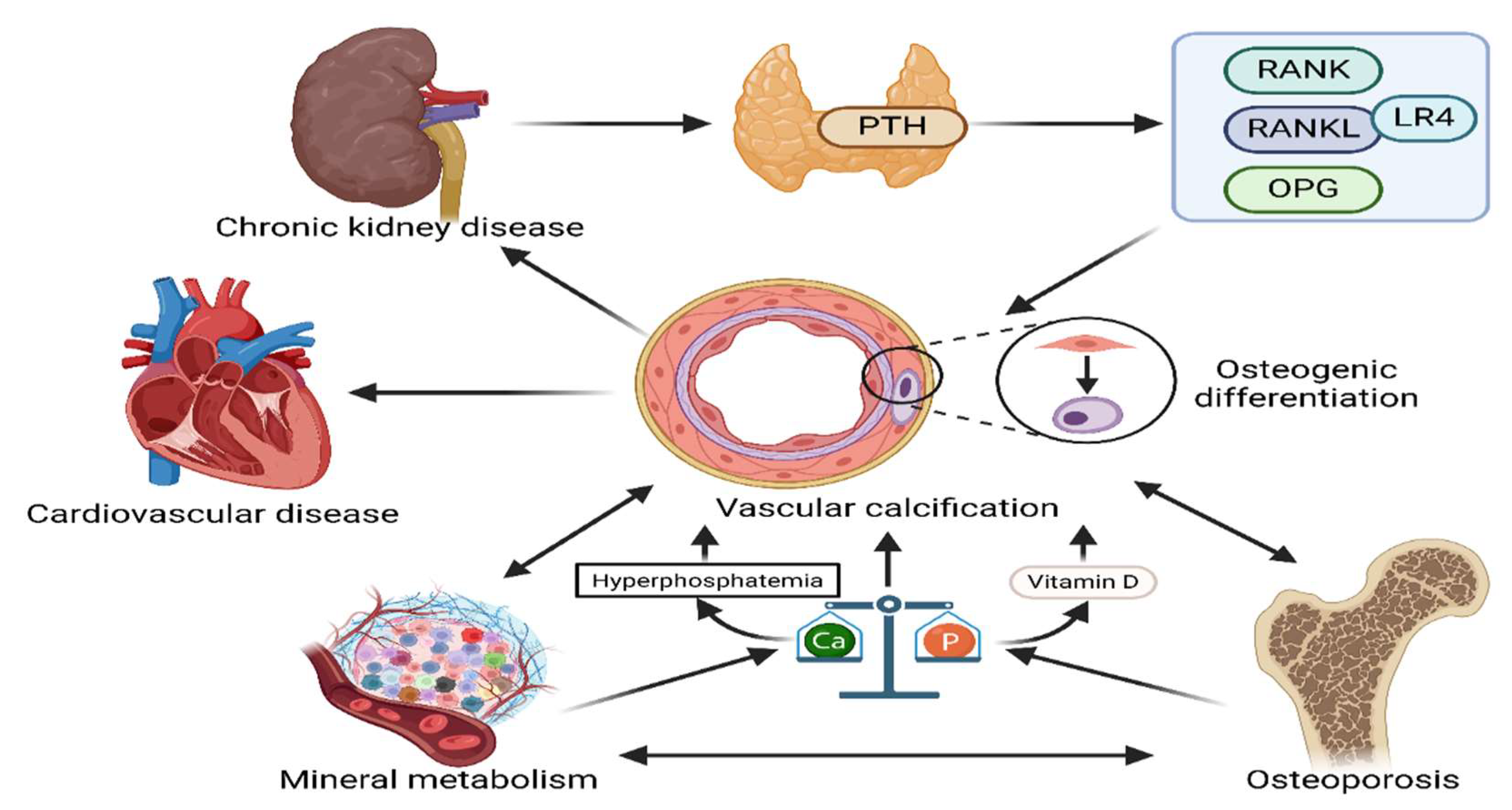

3. Vascular Calcification

Diagnostic Methods

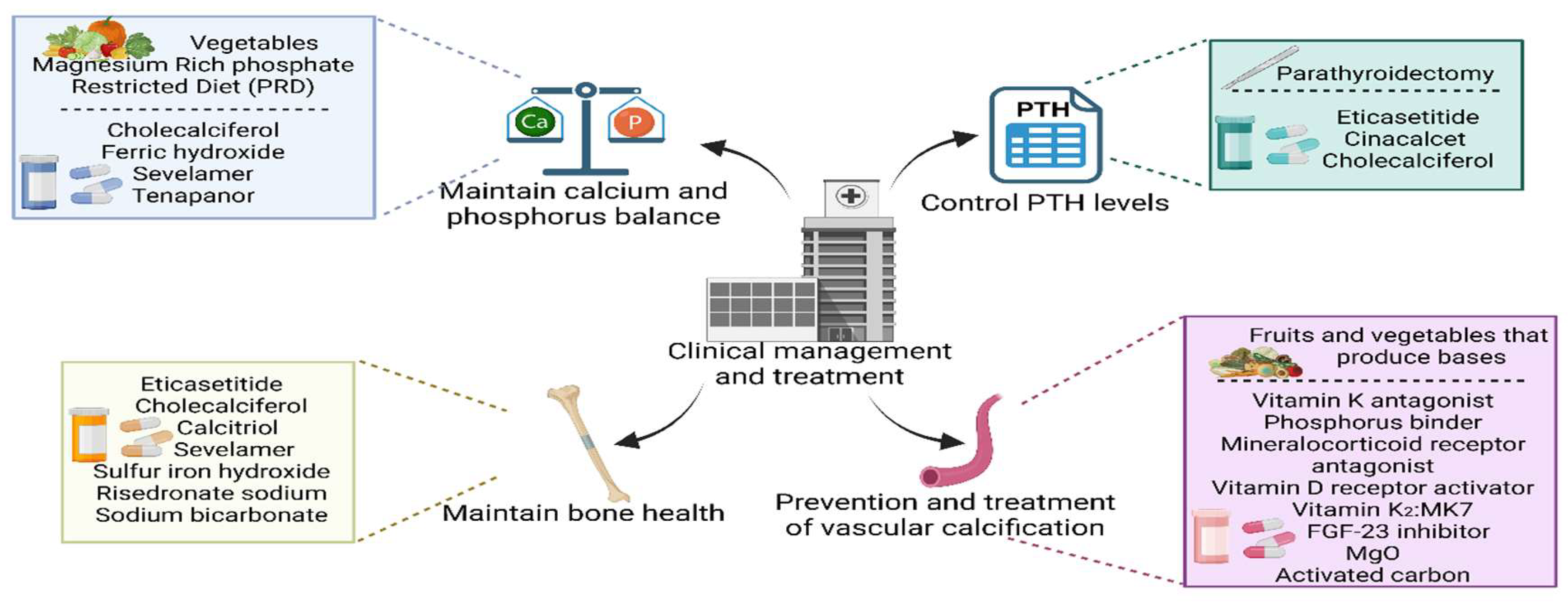

Clinical Management and Treatment

1. Development of Therapeutic Strategies to Maintain Calcium and Phosphorus Balance

2. Therapeutic Advances in Controlling PTH Levels

3. Progress in the Maintenance of Bone Health

4. Advances in the Prevention and Treatment of Vascular Calcification

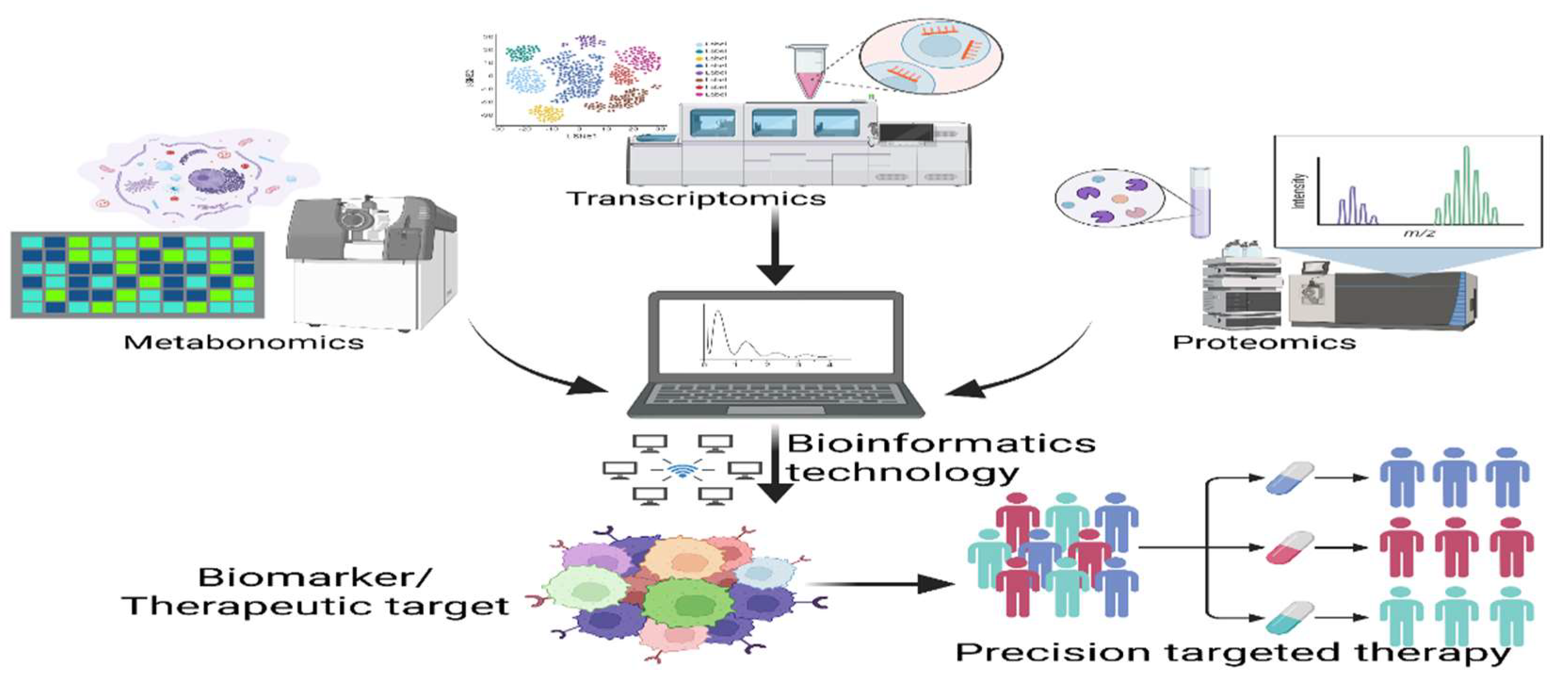

Emerging Research and Future Directions

1. Biomarker Research: Clinical Value and Research Progress of Novel Biomarkers

2. Application of Multi-Omics Technologies: Genomics, Proteomics and Metabolomics in CKD-MBD Research

Conclusion

Funding

Competing interests

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Availability of data and materials

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| CKD-MBD | Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder |

| PTH | Parathyroid Hormone |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| FGF23 | Fibroblast growth factor 23 |

| SHTP | Secondary hyperparathyroidism |

| CaSR | Calcium sensitive receptor |

| CPP2 | Secondary calciprotein particles |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-κ B Ligand |

| NPT2a | Sodium Phosphate Transporter 2a |

| NPT2c | Sodium Phosphate Transporter 2c |

| EGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| LCN2 | Lipocalin 2 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor beta |

| Wnts | Wingless and Int-1 related proteins |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| Hedgehog | Hedgehog signaling pathway |

| Notch | Notch signaling pathway |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-κB |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| LGR4 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 4 |

| RSPO | R-spondins |

| OC | Osteocalcin |

| TNF-alpha | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-1B | Interleukin-1beta |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| BALP | Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase |

| DXA | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| HR-pQCT | High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography |

| TBS | Trabecular Bone Score |

| VMR | Vitamin D metabolite ratio |

| PRD | Phosphate-restricted diet |

| PTX | Parathyroidectomy |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| CTX | C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| PINP | Procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide |

| IPTH | Intact parathyroid hormone |

| AST-120 | Adsorptive Sorbent for Toxic Substance |

| QSP | Quantitative systems pharmacology |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| TNFR1 | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1 |

| TNFR2 | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 2 |

| KIM-1 | Kidney Injury Molecule-1 |

| SuPAR | Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor |

| ALKBH1 | AlkB Homolog 1 |

| SIRT6 | Sirtuin 6 |

| Runx2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| PPARG | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

References

- Aguilar A, Gifre L, Ureña-Torres P, Carrillo-López N, Rodriguez-García M, Massó E, et al. Pathophysiology of bone disease in chronic kidney disease: from basics to renal osteodystrophy and osteoporosis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1177829. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B H, Chong F L, Yuan C C, Liu Y L, Yang H M, Wang W W, et al. Fucoidan ameliorates renal injury-related calcium-phosphorus metabolic disorder and bone abnormality in the ckd-mbd model rats by targeting fgf23-klotho signaling axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586725. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z H, Li G, Zhang L, Chen J, Chen X, Zhao J, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline of chronic kidney disease – mineral and bone disorder (ckd-mbd) in china. Kidney Dis. 2019, 5, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada S, Nakano T. Role of chronic kidney disease (ckd)–mineral and bone disorder (mbd) in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in ckd. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2023, 30, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Huang Z, Fei S, Ni B, Wang Z, Chen H, et al. Vascular calcification progression and its association with mineral and bone disorder in kidney transplant recipients. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2276382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nr H, St F, Jl O, Ja H, Ca O, Ds L, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One.

- Bello A K, Okpechi I G, Levin A, Ye F, Damster S, Arruebo S, et al. An update on the global disparities in kidney disease burden and care across world countries and regions. Lancet Glob. Health. 2024, 12, e382–e395. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xu X, Zhang M, Hu C, Zhang X, Li C, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in china: results from the sixth china chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Napoletano A, Provenzano M, Garofalo C, Bini C, Comai G, et al. Mineral bone disorders in kidney disease patients: the ever-current topic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazianas M, Miller P D. Osteoporosis and chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (ckd-mbd): back to basics. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2021, 78, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan Y, Pei W. Advances of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder. Chin. J. Nephrol.

- Ni Lihua, Liu Bicheng, Tang Rining. Research progress of bone mineral density decrease in chronic kidney disease. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 2018, 98, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kuro-o, M. Calcium phosphate microcrystallopathy as a paradigm of chronic kidney disease progression. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2023, 32, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleet J, C. Vitamin d-mediated regulation of intestinal calcium absorption. Nutrients.

- Amarnath S S, Kumar V, Barik S. Vitamin d and calcium and bioavailability of calcium in various calcium salts. Indian J. Orthop. 6: 1).

- Saponaro F, Saba A, Zucchi R. An update on vitamin d metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Role of nutritional vitamin d in chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder: a narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e33477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenngam N, Holick M F. Immunologic effects of vitamin d on human health and disease. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer M B, Pike J W. Mechanistic homeostasis of vitamin d metabolism in the kidney through reciprocal modulation of cyp27b1 and cyp24a1 expression. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 196, 105500. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg V, Ketteler M. Vitamin d and secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease: a critical appraisal of the past, present, and the future. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang Z, Wang M, Miao C, Jin D, Wang H. Mechanism of calcitriol regulating parathyroid cells in secondary hyperparathyroidism. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1020858. [Google Scholar]

- Portales-Castillo I, Simic P. PTH, fgf-23, klotho and vitamin d as regulators of calcium and phosphorus: genetics, epigenetics and beyond. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 992666. [Google Scholar]

- Renke G, Starling-Soares B, Baesso T, Petronio R, Aguiar D, Paes R. Effects of vitamin d on cardiovascular risk and oxidative stress. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wein M N, Kronenberg H M. Regulation of bone remodeling by parathyroid hormone. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer C Z, Kritmetapak K, Singh R J, Vesper H W, Kumar R. High-resolution mass spectrometry for the measurement of pth and pth fragments: insights into pth physiology and bioactivity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN. 2022, 33, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMambro V E, Tian L, Karthik V, Rosen C J, Guntur A R. Effects of pth on osteoblast bioenergetics in response to glucose. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendina-Ruedy E, Rosen C J. Parathyroid hormone (pth) regulation of metabolic homeostasis: an old dog teaches us new tricks. Mol. Metab. 2022, 60, 101480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani G, Elli F M. PTH resistance. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 531, 111311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrove J, Wolf M. Regulation and effects of fgf23 in chronic kidney disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa T, Segre G V, Lee K. Fibroblast growth factor inhibits chondrocytic growth through induction of p21 and subsequent inactivation of cyclin e-cdk2*. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 29347–29352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalhoub V, Ward S C, Sun B, Stevens J, Renshaw L, Hawkins N, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (fgf23) and alpha-klotho stimulate osteoblastic mc3t3.e1 cell proliferation and inhibit mineralization. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2011, 89, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellorin-Font E, Rojas E, Martin K J. Bone disease in chronic kidney disease and kidney transplant. Nutrients. 2022, 15, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciolli F G, Neves K R, Barreto F, Barreto D V, Dos Reis L M, Canziani M E, et al. The complexity of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder across stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun T, Yu X. FGF23 actions in ckd-mbd and other organs during ckd. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Hino R, Yoneya T, et al. FGF-23 transgenic mice demonstrate hypophosphatemic rickets with reduced expression of sodium phosphate cotransporter type iia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 314, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courbon G, Francis C, Gerber C, Neuburg S, Wang X, Lynch E, et al. Lipocalin 2 stimulates bone fibroblast growth factor 23 production in chronic kidney disease. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali S K, Roschger P, Zeitz U, Klaushofer K, Andrukhova O, Erben R G. FGF23 regulates bone mineralization in a 1,25(oh)2 d3 and klotho-independent manner. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt K P, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 6120–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai M, Kinoshita S, Kimoto A, Hasegawa Y, Miyagawa K, Yamazaki M, et al. FGF23 suppresses chondrocyte proliferation in the presence of soluble α-klotho both in vitro and in vivo*. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 2414–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Fan W, Zhong X, Zhang L, Niu J, Gu Y. Klotho/fgf23 and wnt in shpt associated with ckd via regulating mir-29a. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 876–887. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt I, Haffner D, Leifheit-Nestler M. FGF23 and phosphate-cardiovascular toxins in ckd. Toxins. 2019, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernaro V, Longhitano E, Calabrese V, Casuscelli C, Di Carlo S, Spinella C, et al. Progress in pharmacotherapy for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in renal failure. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2023, 24, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel A, Ureña-Torres P, Bover J, Luis Fernandez-Martín J, Cohen-Solal M. Bone fragility fractures in ckd patients. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2021, 108, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (ckd-mbd). Kidney Int. Suppl. 2017, 7, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cannata-Andía J B, Martín-Carro B, Martín-Vírgala J, Rodríguez-Carrio J, Bande-Fernández J J, Alonso-Montes C, et al. Chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorders: pathogenesis and management. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2021, 108, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner C, A. The basics of phosphate metabolism. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 39, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiizaki K, Tsubouchi A, Miura Y, Seo K, Kuchimaru T, Hayashi H, et al. Calcium phosphate microcrystals in the renal tubular fluid accelerate chronic kidney disease progression. J. Clin. Invest.131,e145693.

- Chen T, Wang Y, Hao Z, Hu Y, Li J. Parathyroid hormone and its related peptides in bone metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114669. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L T, Chen L R, Chen K H. Hormone-related and drug-induced osteoporosis: a cellular and molecular overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur R, Singh R. Mechanistic insights into ckd-mbd-related vascular calcification and its clinical implications. Life Sci. 1: B), 1211.

- Hsu C Y, Chen L R, Chen K H. Osteoporosis in patients with chronic kidney diseases: a systemic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen L, Koivuviita N, Seppänen M, Kröger H, Tong X, Löyttyniemi E, et al. Association between bone mineral metabolism and vascular calcification in end-stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Guo Y, Diao Z, Guo W, Liu W. Genome-wide identification of lncrnas and mrnas differentially expressed in human vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by high phosphorus. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin D, Lin L, Xie Y, Jia M, Qiu H, Xun K. NRF2-suppressed vascular calcification by regulating the antioxidant pathway in chronic kidney disease. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2022, 36, e22098. [Google Scholar]

- Cutini P H, Campelo A E, Massheimer V L. Vascular response to stress: protective action of the bisphosphonate alendronate. Vasc. Med. Lond. Engl. 2022, 27, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-López N, Martínez-Arias L, Alonso-Montes C, Martín-Carro B, Martín-Vírgala J, Ruiz-Ortega M, et al. The receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand receptor leucine-rich repeat-containing g-protein-coupled receptor 4 contributes to parathyroid hormone-induced vascular calcification. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2021, 36, 618–631. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villabrille S, Martín-Vírgala J, Martín-Carro B, Baena-Huerta F, González-García N, Gil-Peña H, et al. RANKL, but not r-spondins, is involved in vascular smooth muscle cell calcification through lgr4 interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro M, Barbuto S, Gallieni M, Cossettini A, Re Sartò G V, Cosmai L, et al. Real-world usage of chronic kidney disease - mineral bone disorder (ckd-mbd) biomarkers in nephrology practices. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galassi A, Fasulo E M, Ciceri P, Casazza R, Bonelli F, Zierold C, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d as predictor of renal worsening function in chronic kidney disease. results from the pascal-1,25d study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 840801. [Google Scholar]

- Desbiens L C, Sidibé A, Ung R V, Mac-Way F. FGF23-klotho axis and fractures in patients without and with early ckd: a case-cohort analysis of cartagene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2502–e2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonston D, Grabner A, Wolf M. FGF23 and klotho at the intersection of kidney and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udagawa N, Koide M, Nakamura M, Nakamichi Y, Yamashita T, Uehara S, et al. Osteoclast differentiation by rankl and opg signaling pathways. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2021, 39, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutka M, Bobiński R, Wojakowski W, Francuz T, Pająk C, Zimmer K. Osteoprotegerin and rankl-rank-opg-trail signalling axis in heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin W C, Lee M C, Chen Y C, Hsu B G. Inverse association of serum osteocalcin and bone mineral density in renal transplant recipients. Tzu-Chi Med. J. 2022, 35, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Haarhaus M, Cianciolo G, Barbuto S, Manna G L, Gasperoni L, Tripepi G, et al. Alkaline phosphatase: an old friend as treatment target for cardiovascular and mineral bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. Nutrients.

- Rasmussen N H H, Dal J, Kvist A V, Van den Bergh J P, Jensen M H, Vestergaard P. Bone parameters in t1d and t2d assessed by dxa and hr-pqct - a cross-sectional study: the diafall study. Bone. 2023, 172, 116753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevroja E, Cafarelli F P, Guglielmi G, Hans D. DXA parameters, trabecular bone score (tbs) and bone mineral density (bmd), in fracture risk prediction in endocrine-mediated secondary osteoporosis. Endocrine. 2021, 74, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata M, Minami M, Yoshida K, Yang T, Yamamoto Y, Takayama N, et al. Calcium-binding protein s100a4 is upregulated in carotid atherosclerotic plaques and contributes to expansive remodeling. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalbary M, Sobh M, Elnagar S, Elhadedy M A, Elshabrawy N, Abdelsalam M, et al. Management of osteoporosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Coop. Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 2022, 33, 2259–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The role of bone biopsy in the management of ckd-mbd - pubmed[EB].

- Favero C, Carriazo S, Cuarental L, Fernandez-Prado R, Gomá-Garcés E, Perez-Gomez M V, et al. Phosphate, microbiota and ckd. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi A, Bhatt N, Rossetti S, Beto J. Management of hyperphosphatemia in end-stage renal disease: a new paradigm. J. Ren. Nutr. 2021, 31, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi Y, Yamaguchi S, Hamano T, Sakaguchi Y, Shimomura A, Namba-Hamano T, et al. Effect of cholecalciferol on serum hepcidin and parameters of anaemia and ckd-mbd among haemodialysis patients: a randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15500. [Google Scholar]

- Ketteler M, Sprague S M, Covic A C, Rastogi A, Spinowitz B, Rakov V, et al. Effects of sucroferric oxyhydroxide and sevelamer carbonate on chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder parameters in dialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2019, 34, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Kobayashi S, Kusakabe M, Ohara M, Nakanishi K, Akizawa T, et al. Tenapanor for peritoneal dialysis patients with hyperphosphatemia: a phase 3 trial. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg C, Zelnick L R, Block G A, Chertow G M, Chonchol M, Hoofnagle A, et al. Differential effects of phosphate binders on vitamin d metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2020, 35, 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Tang P K, Van den Broek D H N, Jepson R E, Geddes R F, Chang Y M, Lötter N, et al. Dietary magnesium supplementation in cats with chronic kidney disease: a prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 2180–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzoń-Norwicz M, Norwicz S, Sowa-Kućma M, Gala-Błądzińska A. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease: pathomechanism and current treatment possibilities. Endokrynol. Pol. 2023, 74, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramitsu T, Hasegawa Y, Futamura K, Okada M, Goto N, Narumi S, et al. Treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism focusing on parathyroidectomy. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1169793. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardor J, De Mul A, Bacchetta J, Schmitt C P. Impact of cinacalcet and etelcalcetide on bone mineral and cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2023, 21, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang A Y M, Lo W K, Cheung S C W, Tang T K, Yau Y Y, Lang B H H. Parathyroidectomy versus oral cinacalcet on cardiovascular parameters in peritoneal dialysis patients with advanced secondary hyperparathyroidism (proceed): a randomized trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2023, 38, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Karaboyas A, Muenz D, Fuller D S, Desai P, Lin T C, Robinson B M, et al. Etelcalcetide utilization, dosing titration, and chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disease (ckd-mbd) marker responses in us hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2022, 79, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujita M, Doi Y, Obi Y, Hamano T, Tomosugi T, Futamura K, et al. Cholecalciferol supplementation attenuates bone loss in incident kidney transplant recipients: a prespecified secondary endpoint analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dudar I, Shifris I, Dudar S, Kulish V. Current therapeutic options for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: a 12-month comparative study. Pol. Merkur. Lek. Organ Pol. Tow. Lek. 2022, 50, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Stathi D, Fountoulakis N, Panagiotou A, Maltese G, Corcillo A, Mangelis A, et al. Impact of treatment with active vitamin d calcitriol on bone turnover markers in people with type 2 diabetes and stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Bone. 2023, 166, 116581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto T, Inoue D, Maehara M, Oikawa I, Shigematsu T, Nishizawa Y. Efficacy and safety of once-monthly risedronate in osteoporosis subjects with mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease: a post hoc subgroup analysis of a phase iii trial in japan. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2019, 37, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed M L, Horwitz E J, Dobre M A, Abramowitz M K, Zhang L, Lo Y, et al. Effects of sodium bicarbonate in ckd stages 3 and 4: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2020, 75, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya N, Munoz-Maldonado Y, Simoni J, Wesson D E. Fruit and vegetable treatment of chronic kidney disease-related metabolic acidosis reduces cardiovascular risk better than sodium bicarbonate. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 49, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratky V, Valerianova A, Hruskova Z, Tesar V, Malik J. Increased cardiovascular risk in young patients with ckd and the role of lipid-lowering therapy. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 26, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Tandon S, Tandon C. An update on vascular calcification and potential therapeutics. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanova L Y, Beketov V D, Milovanova S Y, Taranova M V, Kozlov V V, Pasechnik A I, et al. Effect of vitamin d receptor activators on serum klotho levels in 3b-4 stages chronic кidney disease patients: a prospective randomized study. Ter. Arkh. 2021, 93, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Kaesler N, Schurgers L J, Floege J. Vitamin k and cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease patients. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiyarakseree N, Phannajit J, Naiyarakseree W, Mahatanan N, Asavapujanamanee P, Lekhyananda S, et al. Effect of menaquinone-7 supplementation on arterial stiffness in chronic hemodialysis patients: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen E A, Eelderink C, Hoekstra T, Van Ballegooijen A J, Raijmakers P, Beulens J W, et al. Reversal of arterial disease by modulating magnesium and phosphate (roadmap-study): rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial assessing the effects of magnesium citrate supplementation and phosphate-binding therapy on arterial stiffness in moderate chronic kidney disease. Trials. 2022, 23, 769. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Obi Y, Monden C, Oka T, Yamaguchi S, et al. A randomized trial of magnesium oxide and oral carbon adsorbent for coronary artery calcification in predialysis ckd. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN. 2019, 30, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer F, Buehling S S, Masyout J, Malzahn U, Hauser T, Auer T, et al. Protective effects of spironolactone on vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 582, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao Y, Wang G, Li Y, Lv C, Wang Z. Effects of oral activated charcoal on hyperphosphatemia and vascular calcification in chinese patients with stage 3-4 chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2019, 32, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaweda A E, Lederer E D, Brier M E. Artificial intelligence-guided precision treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2022, 11, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervloet, M. Renal and extrarenal effects of fibroblast growth factor 23. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Debnath N, Mosoyan G, Chauhan K, Vasquez-Rios G, Soudant C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of plasma and urine biomarkers for ckd outcomes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN. 2022, 33, 1657–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arrigo G, Mallamaci F, Pizzini P, Versace M C, Tripepi G L, Zoccali C, et al. MO499CKD-mbd biomarkers and ckd progression: an analysis by joint models. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 0019.

- Laster M, Pereira R C, Noche K, Gales B, Salusky I B, Albrecht L V. Sclerostin, osteocytes, and wnt signaling in pediatric renal osteodystrophy. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang L, Su X, Li W, Tang L, Zhang M, Zhu Y, et al. ALKBH1-demethylated dna n6-methyladenine modification triggers vascular calcification via osteogenic reprogramming in chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 131, e146985–146985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li W, Feng W, Su X, Luo D, Li Z, Zhou Y, et al. SIRT6 protects vascular smooth muscle cells from osteogenic transdifferentiation via runx2 in chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e150051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherkhani A, Farrokhi Yekta R, Mohseni M, Saidijam M, Arefi Oskouie A. Chronic kidney disease: a review of proteomic and metabolomic approaches to membranous glomerulonephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and iga nephropathy biomarkers. Proteome Sci. 2019, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si S, Liu H, Xu L, Zhan S. Identification of novel therapeutic targets for chronic kidney disease and kidney function by integrating multi-omics proteome with transcriptome. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin R F, Deo R, Ren Y, Wang J, Zheng Z, Shou H, et al. Proteomics of ckd progression in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köttgen A, Raffler J, Sekula P, Kastenmüller G. Genome-wide association studies of metabolite concentrations (mgwas): relevance for nephrology. Semin. Nephrol. 2018, 38, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen J, Liu Y, Wang Q, Chen H, Hu Y, Guo X, et al. Integrated network pharmacology, transcriptomics, and metabolomics analysis to reveal the mechanism of salt eucommiae cortex in the treatment of chronic kidney disease mineral bone disorders via the pparg/ampk signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 314, 116590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novel biomarkers of bone metabolism - pmc[EB].

- Thadhani R I, Rosen S, Ofsthun N J, Usvyat L A, Dalrymple L S, Maddux F W, et al. Conversion from intravenous vitamin d analogs to oral calcitriol in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN. 2020, 15, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur A, Ahn J B, Sutton W, Chu N M, Gross A L, Segev D L, et al. Secondary hyperparathyroidism (ckd-mbd) treatment and the risk of dementia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2022, 37, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Evenepoel P, Cunningham J, Ferrari S, Haarhaus M, Javaid M K, Lafage-Proust M H, et al. European consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in chronic kidney disease stages g4–g5d. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam S, Wong M M Y, Jha V. Sustainable development goals: challenges and the role of the international society of nephrology in improving global kidney health. Kidney360. 2023, 4, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor | Source | Main effect | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↓Calcium | Kidney Intestine |

↑SPTH ↑Phosphate excretion |

[12,13] |

| ↑Phosphate | Kidney | ↑SPTH ↓1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis ↓Calcium |

[9] |

| ↓Vitamin D | Kidney | ↑Parathyroid hormone secretion ↑Phosphate ↓Calcium |

[18,20,21] |

| ↑Parathyroid hormone | Parathyroid gland | ↓Calcium ↑Phosphate ↑FGF23 levels |

[12,28,29] |

| ↑FGF23 | Bone | ↑Phosphate excretion ↓1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis |

[32,33,34] |

| ↓Klotho | Kidney | ↑FGF23 levels | [29] |

| Styles | Mechanisms | Effects | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGF23 | Increases in circulating FGF23 levels combined with decreases in renal klotho expression lead to klotho-independent effects of FGF23 on the heart. | Left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, atrial fibrillation and death. | [61] |

| Osteoprotegerin | Inhibits RANKL-RANKL receptor interaction to prevent osteoclast formation and osteoclast bone resorption. | Reduces bone resorption. | [62] |

| Osteocalcin | Participates in the mineralization of bone matrix and is a sensitive indicator of the rate of bone formation. | Negative correlation with lumbar spine bone density in kidney transplant recipients. | [64] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Hydrolytic activity of ALP regulates the mineralization inhibitor PPi. | Regulates dysregulation of calcium phosphate metabolism, inflammation, osteogenic gene expression, and transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. | [65] |

| Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry | Areal BMD measurements. | Assess Bone Density. | [66] |

| High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography | Trabecular architecture Volumetric BMD. | Detailed information on bone microstructure. | [66,67] |

| MRI | Cortical porosity Marrow perfusion, and molecular diffusion. | Provides unique advantages in assessing soft tissue and vascular calcifications. | [68] |

| Trabecular Bone Score | Lumbar Spine DXA Images. | Assesses the condition of bone microarchitecture. | [69] |

| Bone biopsy | Observes and analyzes bone tissue samples directly. | Provides detailed information on bone mineralization, bone formation and bone resorption. | [69,70] |

| Treatments | Ways | Influences | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholecalciferol supplementation | Oral | Increasing serum ferritin-25 levels in hemodialysis patients in the short term and erythropoietin resistance in the long term, reducing whole PTH concentrations, suggesting a significant role in the treatment of SHPT, attenuating mineral density loss in lumbar vertebrae after renal transplantation and eliminating vitamin D deficiency. | [73,83] |

| Phosphate-binding agents iron hydroxide or sevelamer carbonate | Oral | Reducing serum phosphorus levels, but also significantly reducing serum FGF23, rising levels of bone formation markers. | [74] |

| Tenapanor | Oral | Reducing phosphorus levels in serum. | [75] |

| A magnesium-rich Phosphate-restricted diet | Oral | Stabilizing plasma FGF23 and prevent hypercalcemia. | [77] |

| Cinacalcet | Oral | Decreasing PTH secretion to treat SHPT and lowering blood calcium and phosphorus levels without increasing alkaline phosphatase. | [80] |

| Etelcalcetide | Intravenous injection | Reducing parathyroid hormone levels in hemodialysis patients, declining fracture incidence. | [82,84] |

| Risedronate Sodium | Oral | Suppressing Bone Conversion and Increasing BMD in Japanese Patients with Mild to Moderate Chronic Kidney Disease Primary Osteoporosis. | [86] |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Oral or intravenous injection | Increasing serum bicarbonate and decreasing potassium levels, Improving metabolic acidosis and stabilizing estimated glomerular filtration rate. | [87,88] |

| Vitamin D Receptor Activator | Oral or inject | Controlling parathyroid hormone levels and higher serum Klotho. | [91] |

| Vitamin K2 | Oral | Decreasing circulating levels of dephosphorylated uncarboxylated matrix gamma-carboxyglutamate protein and decreasing progression of arterial stiffness in diabetic patients on chronic hemodialysis were shown in patients with end-stage renal disease. | [92,93] |

| Spironolactone | Oral | Improving vascular calcification. | [96] |

| Activated Carbon | Oral | Delaying the onset of hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease and delaying the development of vascular calcification in patients with stage 3-4 CKD. | [97] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).