Submitted:

06 November 2023

Posted:

07 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

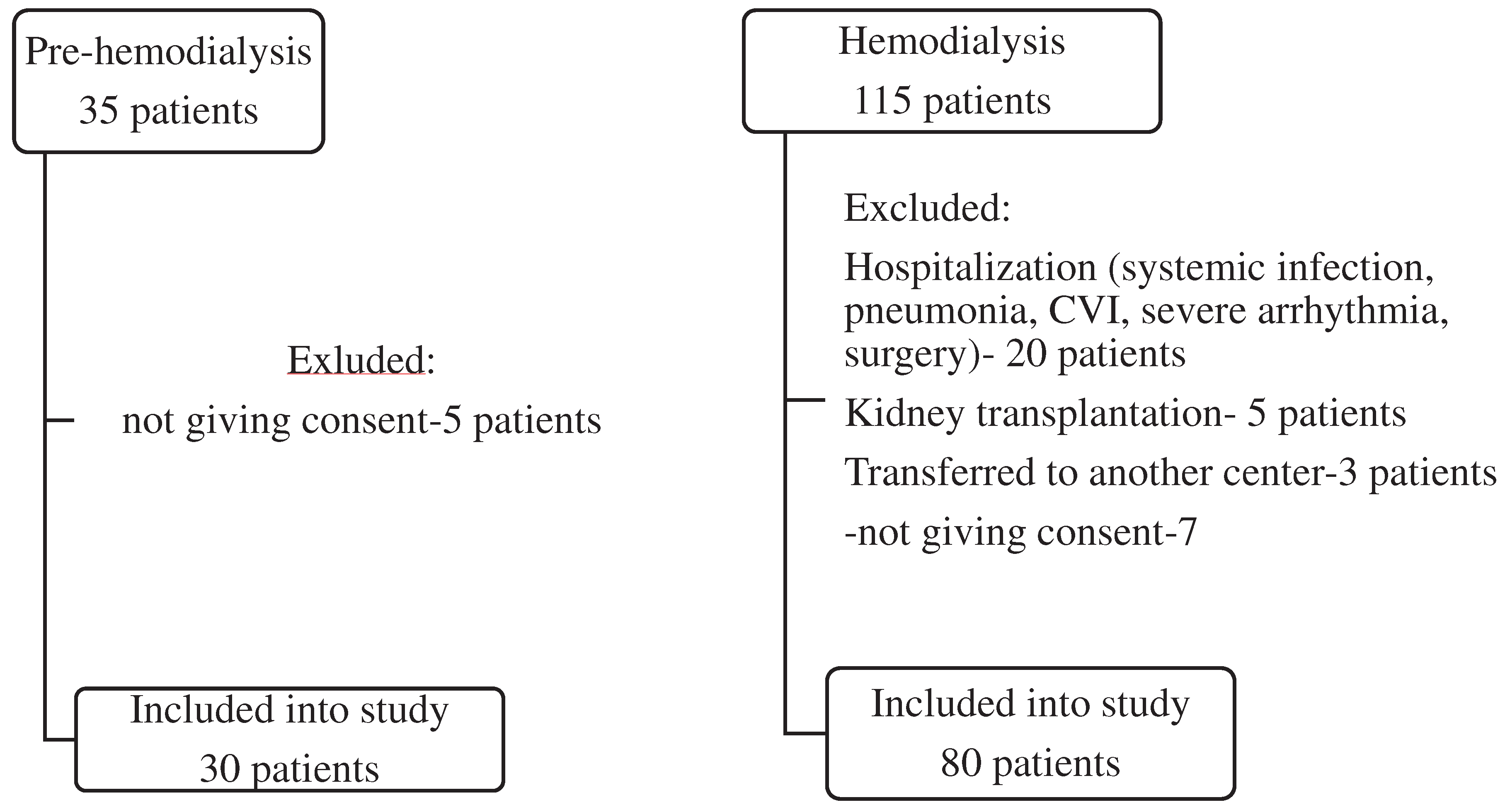

2.1. Patients

2.2. Biochemical analyses

2.3. Calcification assessment

2.4. Brachial blood pressure

2.5. Statistical analysis

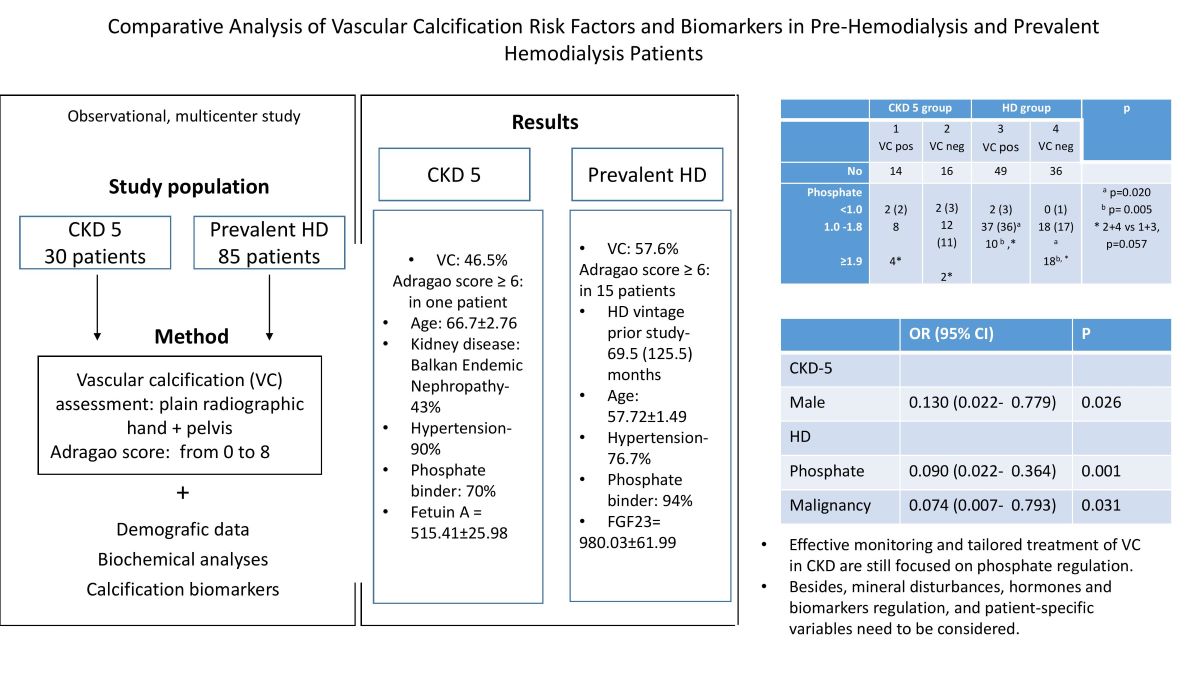

3. Results

3.1. Study population

3.2. Laboratory analyses

3.3. Predictors of vascular calcification in studied groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Budoff MJ, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, et al; CRIC Study Investigators. Relationship of estimated GFR and coronary artery calcification in the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(4):519-26. PMID: 21783289; PMCID: PMC3183168. [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum BR, Adeney KL, de Boer IH, Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS. Incidence and progression of coronary calcification in chronic kidney disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Kidney Int 2009;76(9): 991-8. Epub 2009 Aug 19. PMID: 19692998; PMCID: PMC3039603. [CrossRef]

- Schlieper G, Schurgers L, Brandenburg V, Reutlings - Perger C, Floege J. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: an update. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 31–9. Epub 2015 Apr 26. PMID: 25916871. [CrossRef]

- Gungor O, Kocyigit I, Yilmaz MI, Sezer S. Role of vascular calcification inhibitors in preventing vascular dysfunction and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2018;31(1):72-81. Epub 2017 Jun 13. PMID: 28608927. [CrossRef]

- Wolf M. Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 737–47, Epub 2012 May 23. PMID: 22622492; PMCID: PMC3434320. [CrossRef]

- London GM, Marchais SJ, Guérin AP, Métivier F. Arteriosclerosis, vascular calcifications and cardiovascular disease in uremia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005; 14(6):525-31. PMID: 16205470. [CrossRef]

- Kakani E, Elyamny M, Ayach T, El-Husseini A. Pathogenesis and management of vascular calcification in CKD and dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2019;32(6):553-561. Epub 2019 Aug 29. PMID: 31464003. [CrossRef]

- Ketteler M, Block GA, Evenepoel P, et al. Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) guideline update: what’s changed and why it matters. Kidney Int. 2017;92:26–36. [CrossRef]

- Adragao T, Pires A, Lucas C, et al. A simple vascularcalcification score predicts cardiovascular risk in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2004;19:1480–1488. Epub 2004 Mar 19. PMID: 15034154. [CrossRef]

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013;34(28):2159-2219. Epub 2013 Jun 14. PMID: 23771844. [CrossRef]

- Gorriz JL, Molina P, Cerveron MJ, et al. Vascular calcification in patients with nondialysis CKD over 3 years. Clin J Am SocNephrol 2015;10: 654-666. [CrossRef]

- Damjanovic T, Djuric Z, Markovic N, Dimkovic S, Radojicic Z, Dimkovic N. Screening of vascular calcifications in patients with end-stage renal diseases. Gen. Physiol. Biophys 2009;28: 277–283.

- Zhang H, Li G, Yu X, et al; China Dialysis Calcification Study Group. Progression of Vascular Calcification and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Receiving Maintenance Dialysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2310909. PMID: 37126347; PMCID: PMC10152309. [CrossRef]

- Wu PY, Lee SY, Chang KV, Chao CT, Huang JW. Gender-Related Differences in Chronic Kidney Disease-Associated Vascular Calcification Risk and Potential Risk Mediators: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9(8):979. PMID: 34442116; PMCID: PMC8394860. [CrossRef]

- Petkovic N, Ristic S, Marinkovic J, Maric R, Kovacevic M, DjukanovicLj. Differences in risk factors and prevalence of vascular calcification between pre-dialysis and hemodialysis Balkan nephropathy patients. Medicina 2018;54: 4;. [CrossRef]

- Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1478–83. PMID: 10816185. [CrossRef]

- Lezaic V, Tirmenstajn-Jankovic B, Bukvic D, et al. Efficacy of hyperphosphatemia control in the progression of chronic renal failure and the prevalence of cardiovascular calcification. Clin Nephrol. 2009;71(1):21-9. PMID: 19203546. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick J, Kestenbaum B, Chonchol M. Phosphate and cardiovascular disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(2):113–9. [CrossRef]

- Neven E, D’Haese PC. Vascular calcification in chronic renal failure. Circulation Res. 2011;108:249–64. [CrossRef]

- Xiong L, Chen QQ, Cheng Y, et al. The relationship between coronary artery calcification and bone metabolic markers in maintenance hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2023;24(1):238. PMID: 37582785; PMCID: PMC10428586. [CrossRef]

- NKF-KDOQI Guidelines. Available from: http://www.kidney. org/professionals/KDOQI/guideline up HD PD VA/index.htm [accessed 21.05.2023].

- Cannata-Andia JB, Rodriguez GM, Gomez AC. Osteoporosis and adynamic bone in chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol 2013;26:73-80. PMID: 23023723. [CrossRef]

- Adragao T, Ferreira A, Frazao JM, et al. Higher mineralized bone volume is associated with a lower plain X-Ray vascular calcification score in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179868. PMID: 28686736; PMCID: PMC5501435. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Chen D, Chen Z, et al. Relationship between vascular calcification and bone mineral density in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(10):1931-1940.

- Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2432-2439. [CrossRef]

- Nasrallah MM, El-Shehaby AR, Salem MM, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) is indepenently correlated to aortic calcification in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2010; 25: 2679–2685. Epub 2010 Feb 22. PMID: 20176609. [CrossRef]

- Desjardins L, Liabeuf S, Renard C, et al; European Uremic Toxin (EUTox) Work Group. FGF23 is independently associated with vascular calcification but not bone mineral density in patients at various CKD stages. Osteoporos Int 2012;23: 2017–25. Epub 2011 Nov 23. PMID: 22109743s. 2020;32(10):1931-1940. [CrossRef]

- Baralić M, Brković V, Stojanov V, et al. Dual Roles of the Mineral Metabolism Disorders Biomarkers in Prevalent Hemodilysis Patients: In Renal Bone Disease and in Vascular Calcification. J Med Biochem 2019;38(2):134-144. PMID: 30867641; PMCID: PMC6411002. [CrossRef]

- Scialla JJ, Lau WL, Reilly MP, et al; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney Int 2013;83: 1159–68. Epub 2013 Feb 6. PMID: 23389416; PMCID: PMC3672330. [CrossRef]

- Akbari M, Nayeri H, Nasri H. Association of fetuin-A with kidney disease; a review on current concepts and new data. J Nephropharmacol 2019; 8(2): e14. [CrossRef]

- Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2003;361:827–33. [CrossRef]

- Ulutas O, Taskapan MC, Dogan A, Baysal T, Taskapan H. Vascular calcification is not related to serum fetuin-A and osteopontin levels in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2018;50(1):137-142. Epub 2017 Nov 13. PMID: 29134617. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi AR, Olauson H, Witasp A, et al. Increased circulating sclerostin levels in end-stage renal disease predict biopsy-verified vascular medial calcification and coronary artery calcification. Kidney Int 2015;88(6):1356-1364. Epub 2015 Sep 2. PMID: 26331407. [CrossRef]

- Claes KJ, Viaene L, Heye S, Meijers B, d’Haese P, Evenepoel P. Sclerostin: Another vascular calcification inhibitor? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(8):3221-8. Epub 2013 Jun 20. PMID: 23788689. [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk B, Wyskida K, Ficek J, et al. Relationship between plasma levels of sclerostin, calcium-phosphate disturbances, established markers of bone turnover, and inflammation in haemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2019;51(3):519-526. Epub 2018 Dec 24. PMID: 30584645; PMCID: PMC6424932. [CrossRef]

| All | Pre-HD (No=30) |

HD (No=85) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics Age, years Sex, m/f |

60.10±1.36 59/ 59 |

66.7±2.76 40/45 |

57.72±1.49 19/11 |

0.003 0.141 |

| Underlying kidney disease: (%) GN Nephroangiosclerosis APCD DM2 BEN Nephrolithiasis Others |

18 20 10 13 27 13 14 |

3 (10) 6 (20) 2 (6.7) 5 (9.4) 13 (43.3) 1 (3.3) |

15 (17.6) 14 (16.5) 8 (9.4) 8 (9.4) 14 (16.5) 12 (14.1) 14 (16.5) |

0.394 0.779 1.000 0.442 0.005 0.178 |

| Co-morbidities, yes (%) DM2 Hypertension CVD CVI tumor |

16 (15.5) 83 (80.6) 43 (41.7) 11 (10.7) 8 (7.8) |

4 (13.3) 27 (90) 14 (46.7) 2 (6.7) 1 (3.3) |

14 (16.4) 65 (76.7) 34 (34.1) 10 (10.6) 8 (8.2) |

0.778 0.029 0.527 0.728 0.442 |

| Treatment, no (%) | ||||

| ESA Phosphate binder Alpha D3 Antihypertensive |

43 (50) 101 (87.8) 34 (29.6) 78 (67.8) |

7 (23.3) 21 (70) 9 (30) 16 (53.3) |

36 (64.3) 80 (94.1) 25 (29.4) 62 (72.9) |

0.080 0.001 1.000 0.068 |

| VC score, no (%) 0 1-2 ≥ 3 ≥ 6 (8) |

52 (45.2) 22 (19.1) 41 (35.6) 16 (6) |

16 (53.3) 4 (13.3) 10 (33.3) 1 (0) |

36 (42.35) 18 (21.2) 31 (37.47) 15 (6) |

0.393 0.384 0.756 0.030 |

| All | Pre-dialysis (No=30) |

HD (No=85) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol, mmol/L Triglyceride, mmol/L Hemoglobin, g/L S-Glycaemia, mmol/L S creatinine, µmol/L Urea, mmol/L S-Urate, µmol/L S-Sodium, mmol/L Potassium, mmol/L Calcium, mmol/L Phosphate, mmol/L Feritin, µg/L |

4.59±0.16 4.50 (3.85-5.4) 2.01±0.16 1.65 (1.2-2.8) 108.35±2.19 108 (99-116) 16.26±9.8 5.1 (4.2-5.8) 749±23.89 776 (617-891) 22.57±0.76 22.0 (17.8-27.0) 353.4±9.89 345 (308.75-412) 138.38±0.31 138 (136-140) 5.23 ±0.11 5.2 (4.6-5.9) 2.18±0.02 2.19 (2.10-2.29) 1.64±0.04 1.61 (1.3-2.0) 344.6±38.0 296 (95.45-431) |

4.83±0.15 1.4 (0.8) 105.63±2.93 106 (96.7-114.5) 5.28±0.35 5.2 (4.7-5.55) 537.31±51.9 552.5 (318-731.2) 24.88±2.1 23.4 (14.2-32.95) 386.70±24.2 365 (318.6-449.5) 139.87±0.7 141 (138.2-142.2) 4.85±0.1 4.8 (4.2-5.4) 2.16±0.04 2.16 (2.05-2.28) 1.54±0.1 1.53 (1.1-1.8) 150.96±35.4 84.3(50.75-231.87) |

4.59±1.16 4.5 (3.82-5.4) 2.01±1.6 1.65 (1.2-2.8) 108.04±1.34 108 (101.5-116.5) 20.01±13.14 4.9 (4.2-6.05) 824.0 ±21.5 808 (705.5-915) 21.75±0.7 21.0 (17.9-26.0) 342.1±10.2 342.0 (297-409) 137.86±0.33 138.0 (136-140) 5.29±0.08 5.3 (4.7-5.9) 2.19±0.03 2.19 (2.1-2.31) 1.68±0.05 1.65 (1.3-2.03) 390.2±44.9 355 (131.7-490.1) |

0.891 0.804 0.384 0.663 0.000 0.327 0.100 0.001 0.011 0.541 0.247 0.000 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/L iPTH, pg/ml <100* 25(OH)D, ng/ml <29 *(deficiency± insufficiency) |

88.68±3.9 82 (61-108) 228.4±24.9 120 (55.5-314.5) 47 (41.6%) 32.84 ±1.84 26.85 (18.95-47.95) 64 (55.6%) |

80.63±8.8 73.5 (61.5-99.2) 200.9±34.6 200.9 (34.57) 11 (36.6%) 33.02±5.3 24.7 (46.22) 19 (64.28) |

91.52±4.4 87 (60-109 237.5±31.2 118 (49.5-238.5) 36 (42.3%) 32.8±1.9 27.5 (19.2-48.05) 45 (53.6%) |

0.304 0.710 0.879 |

| Fetuin, ng/ml | 416.56±18.78 390 (305-520) |

515.41±25.98 520 (383-600) |

360.96±21.8 339.5 (244.5-432.6) |

0.000 |

| Sclerostin, pg/ml | 3101.43±231.35 2750 (1060-4960) |

3450.5±243.47 3190 (2550-4520) |

2905.1 ±333.1 2105 (811-5105) |

0.103 |

| FGF23, pg/ml | 813.9±58.67 685 (224-1500) |

187.11±33.0 154.5 (71.2-233.6) |

980.03±61.99 1108 (382-1500) |

0.000 |

| Pre HD group | HD group | p | |||

|

1 VC + |

2 VC neg |

3 VC + |

4 VC neg |

||

| Number | 14 | 16 | 49 | 36 | |

| Age, years | 71.7±2.05 | 62.5±4.68 | 58.66±1,98 | 56.43±2.28 | 1 vs 3, 4 p< 0.001 |

| Sex, m/f | 12/2 | 7/9 | 23/26 | 17/19 | 1 vs 2, 3,4 p < 0.02 |

| ESA, yes /no | 2/12 | 5/11 | 20/29 | 16/20 | 1 vs 4 p= 0.05 |

| Phosphate binder, yes/ no | 9/5 | 12/4 | 47/2 | 33/3 | 1 vs 3,4 p<0.03 2 vs 3 p=0.028 |

| Phosphate, mmol/l | 1.57±0.16 | 1.51±0.11 | 1.54±0.06 | 1.87±0.08 | 4 vs 2, 3 p< 0.018 |

| Phosphate range, mmol/l <1.0 1.0 -1.8 ≥1.9 |

2 8 4* |

2 12 2* |

2 37a 10 b ,* |

0 18a 18b, * |

a p=0.020 b p= 0.005 * 2+4 vs 1+3, p=0.057 |

| FGF 23, pg/ml | 140.75 (205) | 156 (165.7) | 1006 (1175) | 1500 (830) | 2 vs 3, 4 p< 0.0001 1 vs 3, 4 p< 0.004 |

| Fetuin A, ng/ml | 552.5(295) | 498 (162) | 326 (204) | 377 (193) | 1 vs 3, 4 p =0.001 2 vs 3, 4 p< 0.003 |

| B | OR | 95% CI for OR | p | ||

| All patients | |||||

| Phosphate | -0.896 | 0.408 | 0.180 0.926 | .032 | |

| (Constant) | 1.692 | 5.431 | |||

| Pre-HD group | |||||

| Sex | - 2.043 | 0.130 | 0.022 0.779 | 0.026 | |

| (Constant) | 0.539 | 1.714 | |||

| HD Group | |||||

| Phosphate | -2.408 | 0.090 | 0.022 0.364 | 0.001 | |

| Tumor | - 2.599 | 0.074 | 0.007 0.793 | 0.031 | |

| (Constant) | 4.492 | 89.295 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).