1. Introduction

Metal halide perovskites (MHP) nanocrystals (NCs) or quantum dots are gaining significant interest owing to their intriguing optical and physical properties, including bandgap tunability via tuning NC size and chemical compositions, high radiative recombination rate, defect tolerance, high absorption coefficient, high photoluminescence (PL) quantum yield, long range coherent coupling, and strong Coulomb interaction.1–4 These excellent properties offer MHP NCs as building blocks for developing highly efficient optoelectronic devices, for example, light-emitting diodes,5,6 photodetectors,7 photovoltaic cells,8–10 lasers,11,12 single photon sources.4,13,14 Three dimensional MHPs generally have a structure of ABX3, where A is a cation can be Cs+ or methylammonium CH3NH3+ (MA), B is divalent metal ion like Pb2+ or Sn2+, X is a halide anion (X = I, Br, Cl). At room temperature, the crystal adopts a cubic phase, consisting of a cubic array of corner-sharing BX6 octahedra, with the A-site cation located within the cuboctahedral cavities. High yields can be achieved using established methods such as hot injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP).15,16 The most common perovskite NCs are CsPbX3 and MAPbX3, because of their ease of synthesis. However, MHP structures are soft and chemically unstable, with dynamic and weak surface ligands binding, and susceptibility to anion-exchange reactions; their stability has always been a large concern and challenge. MHP NCs are affected by external factors such as light, humidity, ambient temperature, and proton exchange reactions, leading to a decrease in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) over time, hindering their practical applications. Several strategies have been proposed and implemented to improve the optoelectronic performance of MHP NCs, such as surface passivation, heterostructure formation, A-site doping, B-site doping, and core/shell structures.17–20 B-site doping is s an effective strategy for enhancing the PLQY of MHP NCs, offering a straightforward synthesis process that preserves the integrity of the perovskite structure. In addition, B-site doping also enables the emergence of new physical phenomena and allows precise tuning of the optical and electronic properties of the material.20–26 Wang et al. doped Eu3+ into CsPbCl3, and the positions of typical emission bands were tuned by adjusting the Eu3+ ion doping amount.27 In general, metallic ions such as Co2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, and rare earth ions are suitable for B-site dopants into MHP NCs, enhancing their optoelectronic properties hold promise for their applications in highly efficient opto-electronic devices.28–32 Among them, Mn2+ is the most sought-after due to its unique chemical and physical properties, such as exhibiting bright and stable PL, introducing magnetic and spintronic properties, and enhancing the optical stability of perovskite materials.21,22,33–36 Not all metallic ions can be doped into perovskites, with the structure ABX3 the Goldschmidt tolerance factor, , should be in the range of 0.76 – 1.13 to ensure the three-dimensional perovskite structure, where rA and rB are the radii of atom A and B, respectively.37,38 The doped metal species are also be constrained by the octahedral coefficient μ, defined by , the stability range for μ is between 0.44 and 0.89.39,40 The incorporation of Mn2+ into the perovskite crystal lattice increases the tolerance factor, improves the structural stability, and enhances the radiation pathways.37,38 Liu et al. elucidated the role of the relative strengths Mn-Cl bond in the precursor and host lattice in incorporating Mn2+ ions into perovskite CsPbX3 NCs. They successfully doped Mn2+ into CsPbCl3 NCs and observed a dual-band emission, which is originated from the energy transfer between the Mn²⁺ ion and the host.41 In addition, cation dopants can suppress non-radiative (NR) recombination due to effectively passivating surface and structural defects, leading to an increase in the PLQY perovskite NCs.42,43 The mechanism of Mn2+ doping is explained through the dynamic exchange of cations and halogen anions. The homologous bond dissociation between Mn-X (halogen) and Pb-X is extremely important, which enables the successful substitution of Pb2+ by Mn2+.44,45

Most Mn2+-doped MHP NCs, particularly CsPbBr3 and CsPbI3, have been synthesized using a hot injection method. While this approach yields high-quality NCs, it requires high reaction temperature, precise control of temperature and reaction time, and poses significant challenges for scale-up. In this study, we synthesized Mn2+-doped MAPbBr3 NC using a simple method, ligand-assisted reprecipitation, at room temperature. We observed PLQY improvement in MAPbBr3 NCs with Mn-dopant, reaching an optimal value of 72% at 17% Mn2+, an increase of 34 % compared to the undoped sample. In addition, Mn2+ doping can passivate the defects of NCs, replacing the vacancy of cation sites without changing the structure of the perovskite material, resulting in significantly improved optical stability. To investigate the effect of Mn2+ on optical and structural stabilities, we monitor the long-term stability of the sample under ambient conditions, conduct optical properties at low temperature, and grow NC superlattices from non-doped and Mn-doped MAPbBr3 NCs. The improvement of NCs quality by Mn2+ doping is a promising strategy to grow a superlattice of MAPbBr3 NCs through a self-assembly process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Lead (II) bromide (99%), methylamine bromide (CH3NH2Br), manganate (II) bromide (99%) n-octylamine (≥99%), oleic acid (≥90%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), toluene, didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB, 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Synthesis of Mn-Doped MAPbBr3 NCs

The method we used to synthesize xMn-CH3NH3PbBr3 NCs is ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP), where x is the mole percentage in the precursors. A combination of 0.2 mmol of CH3NH3Br, 0.2(1-x) mmol of PbBr2, and 0.2x mmol of MnBr2 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.17, 0.2 and 0.25) were mixed in 5 mL DMF with 40 μL oleylamine (OLA) and 400 μL oleic acid (OA) to generate a precursor solution in the standard manufacture of MAPbBr3 NCs. After that, at room temperature, the precursor solution was injected into toluene at a 1:10 volume ratio. The reaction was kept for 10 minutes to form colloidal MAPbBr3 NCs. The product was then centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 minutes. The large crystal size aggregated at the bottom was removed. The upper fraction was then further centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 2 hours to discard the supernatant. The bottom containing NCs was then diluted in toluene to make a NC solution. Since the exact amount of Mn²⁺ incorporated into the perovskite lattice is unknown, we name the Mn-doped samples as xMn-MAPbBr3, where x is the molar ratio of Mn to the total (Pb+Mn).

2.3. Surface Passivation

A mixture of 9.2 mg dimethyldidodecylammonium bromide (DDAB) in toluene (2 mL) was prepared to have the solution of DDAB in toluene (0.01 M). 200 μL of the purified xMn-MAPbBr3 NCs and 10 μL DDAB solution (0.1 M) were mixed and stirred for 1 hour at room temperature.46 Discard the supernatant and disperse the precipitate in 5 mL of toluene.

2.4. Preparation of NC Superlattice

xMn-MAPbBr3 (x = 0 and x = 0.17) NC solutions were used to form a superlattice by the self-assembly method through the gradual evaporation of the solvent. The square pieces of silicon substrate <P-111> 1 cm × 1 cm were placed in a glass petri dish with a diameter of 90 mm. The NC solution was dropped onto the Si substrate with approximately 50 μL. To protect it from ambient light and air currents, the petri dish was covered with a glass lid and loosely wrapped in foil. The superlattice will be formed in about 8 to 10 hours.46

2.5. Characterizations

X-ray diffractions (XRD) were recorded using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Cu Kα with λ = 1.54056 Å, 40 kV, and 40 mA). The samples were prepared by drop-casting NCs solution onto a silicon substrate, <P-111>, for measurements.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging was performed to measure the thickness and morphology of MAPbBr3 superlattice, using a silicon tip operated in semi-contact mode from NTEGRA Spectra II (NT-MDT Inc).

Photoluminescence (PL) confocal scanning: The measurement is equipped with a confocal laser microscope. The excitation and collection were used with a 100x long working-distance objective with a numerical aperture of 0.67. The sample is excited by the femtosecond laser pulses at a wavelength of 400 nm or 800 nm with a pulse duration of <100 fs and a repetition rate of 80 MHz (Mai Tai, Spectra Physics). The PL image was captured using a Galvo mirror scanning system, and the PL signal was recorded via an EM-CCD camera.

Optical Spectroscopy: Absorption spectra were measured with a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, RF-5301PC). A femtosecond laser pulse at 405 nm was used to excite the sample for PL spectral measurements. Using a 10x magnification objective for excitation and collection through a long-pass chromatic mirror and color filter, an Ocean Optics spectrometer was used for this measurement. Time-resolved photoluminescent (TRPL) dynamics were obtained using time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC), PicoHarp300. The samples for PL and TRPL measurements were prepared by drop-casting of NC solution onto a silicon substrate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization of Mn-doped MAPbBr3 NCs

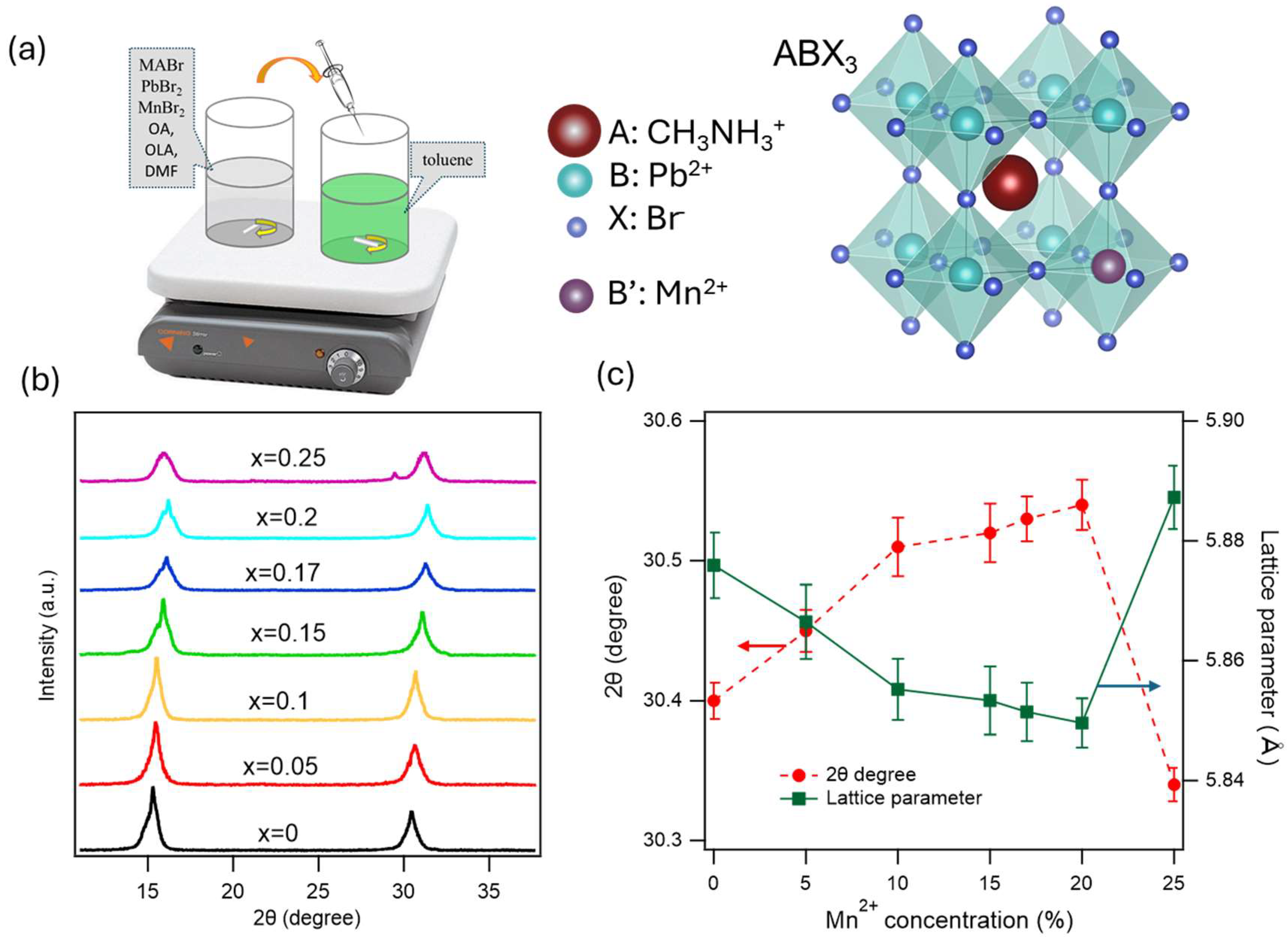

The one-pot synthesis of Mn-doped MAPbBr

3 perovskite NCs using ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP), was described in section 2.2. Briefly, a mixture of precursors including MABr, PbBr

2, MnBr

2 (x molar fraction), OLA, and OA with the desired stoichiometric molar concentrations in a polar DMF solvent was injected into a non-polar anti-solvent toluene container under vigorous stirring at room temperature. The crystal grown is due to a reduction in solubility by anti-solvent, leading to supersaturation and fast nucleation,

Figure 1a. The ligands (OA, OLA) prevent uncontrolled aggregation, and provide colloidal stability and passivate the crystal surface. This synthesis method is simple, a room temperature process, and scalable. In the Mn-doped perovskite, Mn

2+ substitutes for the Pb

2+ cation site. The perovskite structure is maintained even though the cell size was decreased because of the smaller atomic size of Mn²⁺ compared to Pb. The shrinkage of the crystal lattice is reflected in a shift in the XRD pattern. The Mn

2+ ions directly participate in the nucleation process to form MAPb

1-yMn

yBr

3 NCs, within the limit of Mn

2+ concentration, allowing the perovskite structure to be stable. This can be confirmed through the calculation of the tolerance factor and octahedral factor of the perovskite.

37,38,47 These considerations reflect a trade-off between colloidal stability and the successful incorporation of Mn

2+ ions.

Figure 1 presents the XRD patterns of xMn-MAPbBr

3 NCs for various Mn

2+ concentrations. There are two strong diffraction peaks at around 15.2

o and 30.4

o, corresponding to the (100) and (200) for both pure and Mn

2+-doped MAPbBr

3, confirming the cubic phase of perovskite crystal at room temperature.

48,49 No secondary peaks were observed on the XRD patterns, and the shift in the XRD peaks confirms the effective incorporation of Mn

2+ in the MAPbBr

3 lattice. The XRD peak shift increases with increasing doping concentration up to 20% of Mn²⁺, which indicates the incorporation of Mn

2+ in the crystal lattice. It has been reported that doping can induce structural evolution, especially when the size mismatch between the dopant atom and the substituted atom is large, but the small distortion here shows that the lattice contraction and octahedral tilt are not strong enough to produce a discernible structural change.

50 The XRD peak shift to larger angle is shown in

Figure 1c with increasing dopant concentration because of the contraction of the lattice due to the replacement of higher crystal radii Pb

2+ ions (1.12-1.19 Å) by smaller Mn

2+ ions (0.8 Å).

51–53 The different behavior of the XRD shift at x = 0.25 presumably at high Mn²⁺ concentration, the Mn

2+ ions do not substitute Pb

2+ ions rather form segregated crystal phases of MAPbBr

3 and MAMnBr

3 which will lead to lower PLQY. Further research is needed to reveal crystal structures at high Mn²⁺ concentration.

At room temperature, the MAPbBr

3 crystal has the cubic phase, the lattice parameter

a is calculated from the XRD peak (200) using the formula:

54 , where (h k l) are the Miller indices, d is the interplanar spacing, which is calculated using Bragg’s law

nλ = 2d.sinθ. In the XRD,

θ is the diffraction angle and λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray (1.54 Å for Cu Kα), for the first order diffraction n =1. In

Figure 1c, the calculated lattice parameter decreases with increasing Mn²⁺ concentrations, except for the 25% Mn²⁺ dopant. This indicates that the smaller dopant Mn

2+ ions are substituting for Pb

2+ ions, causing a contraction of the lattice. This observation is consistent with Vegard’s law, which states that the lattice parameter changes linearly with composition in a solid.

55

3.2. Optical Characterization of Mn-Doped MAPbBr3 NCs

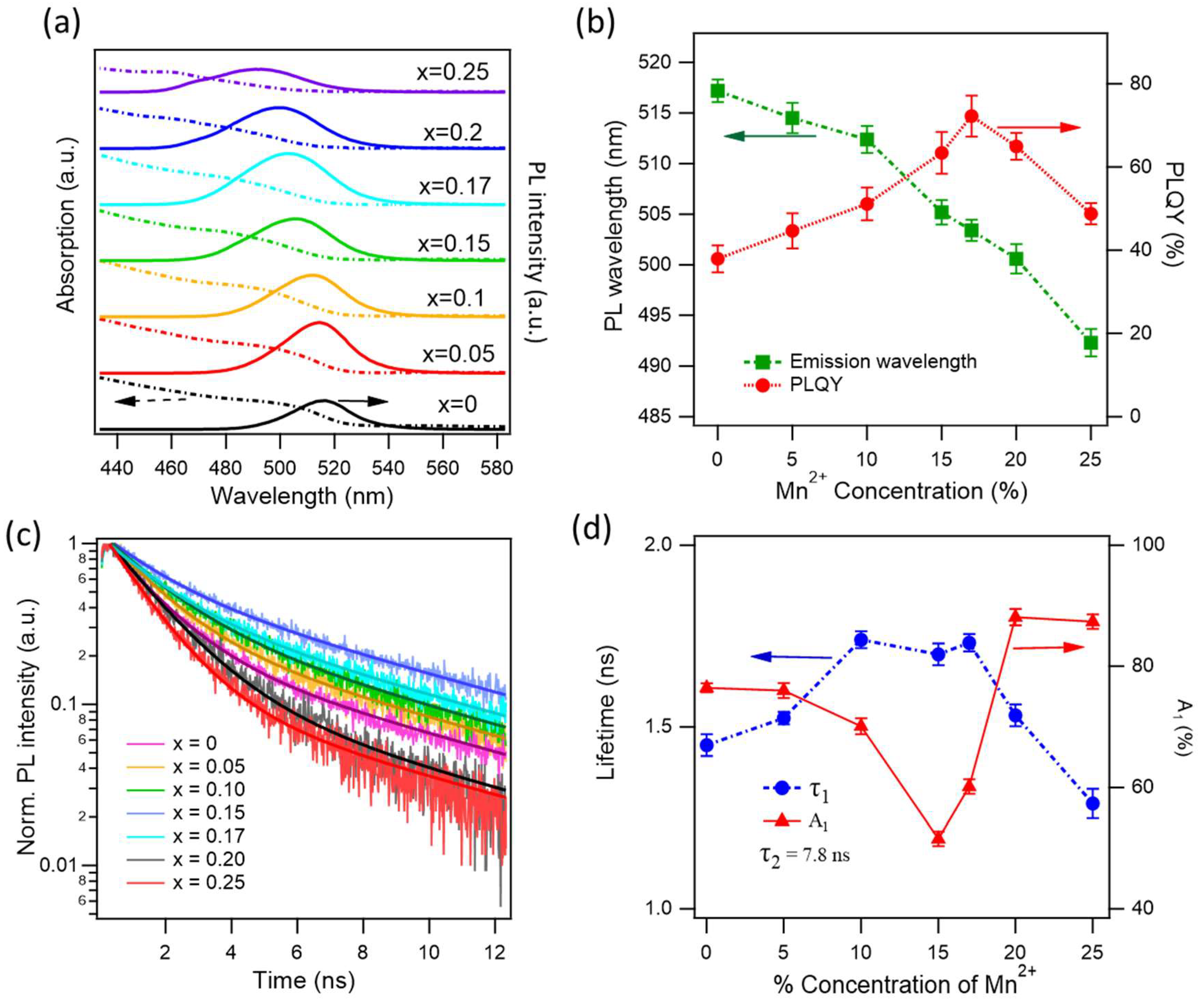

Figure 2 presents the optical characterizations of xMn-MAPbBr

3, with the Mn

2+ concentration increasing from x = 0 to 0.25. We observe a gradual blue shift of the emission wavelength from 517 to 492 nm, in agreement with the previous observations.

56 The absorption, emission, and PLQY measurements were done on NCs in toluene solutions. The blue shift was attributed to the smaller size of NC due to the shrinkage of the crystal lattice when the smaller atomic size Mn

2+ ions substituted for Pb

2+. The reduction of the lattice constant of the cubic parameter was calculated from the XRD pattern,

Figure 1c, which indicates the Mn

2+ ions are incorporated into the perovskite crystal by substituting Pb

2+ ions. The incorporation of Mn

2+ ions in the crystal lattice may also perturb the electronic band structure of the perovskite crystal, although it does not introduce new energy levels. While Mn-dopant into CsPbCl

3 introduced new energy level and dual band emission araises,

21,57 the absence of Mn

2+ emission in Mn-doped CsPbBr

3 or MAPbBr

3 is due to the negligible difference between

4T

1 to

6A

1 band gap of the d-state of Mn

2+ ions and the transition band gap of pure APbBr

3 crystals.

58–60

As the Mn

2+ doping concentration increases, the PLQY increases from 38% for the pure MAPbBr

3 to 72% for the 17 % Mn

2+ concentration. Further increasing Mn

2+ doping concentration results in a drop in the PLQY. At 25% of Mn

2+, the PLQY is 49%,

Figure 2b. The significant PLQY enhancement with increasing Mn

2+ concentration to MAPbBr

3 NCs indicates the efficient reduction of NR recombination pathways. It has been suggested that Mn

2+ ions fill the Pb

2+ vacancies and passivate dangling bonds and defects of crystal surface.

56 Further increasing the Mn

2+ concentration above 20%, leads to a decrease of PLQY, possibly due to the strong distortion of the crystal lattice introducing new defects, or may result in the segregation phase of MAPbBr

3 and MAMnBr

3, forming domain boundaries and defects as the reverse change of the XRD shift,

Figure 1c.

To have better insight into the reduction of NR recombination pathways induced by Mn

2+ doping, we measure time-resolved PL (TRPL) dynamics at various Mn

2+ concentrations, as shown in

Figure 2c. The measurements were performed on thin films, and the resulting dynamics reveal two decay time constants corresponding to radiative and NR recombination. For simplicity, we assume that the radiative rate remains constant across different Mn

2+ concentrations. We performed global fitting of the dynamics, keeping the radiative lifetime fixed for all traces. The fit is used a biexponential function,

, where (

A1, ) and (

A2, ) are the amplitudes and lifetimes of NR and radiative decay channels, respectively. The obtained fitting constants are displayed in

Figure 2d, the radiative lifetime is 7.8 ± 0.1 ns for all traces. The NR lifetime increases from 1.4 to 1.7 ns (at x = 0.1, 0.15, and 0.17), further increasing Mn²⁺ concentration results in the reduction of the NR lifetime. The radiative lifetime of excitons in perovskite NCs has been reported to be largely varying from a few to tens of ns, depending on the NC size and excitation conditions. The NR lifetime was reported to be ~1.5 ns, in agreement with our observation.

61,62 The most important observation here is the percentage of NR amplitude constant,

A1. This represents the weight of the NR channel. As can be seen, the weight of NR is 76% for non-doped NCs and drops to 51% at x = 0.15, and rises to ~87% at x = 0.2 and 0.25. The lowest NR component at x = 0.15 is consistent with the maximum PLQY at x = 0.17. Indeed, the Mn

2+ dopant at an optimal value reduces NR by infilling the Pb

2+ vacancies and passivating defects/dangling bonds. It is worth noting that while the PLQY measurements were performed on solution samples, the TRPL dynamics were measured on NC films, which may lead to some discrepancies between the two measurements.

3.3. Optical Stability of Mn-Doped MAPbBr3 NCs

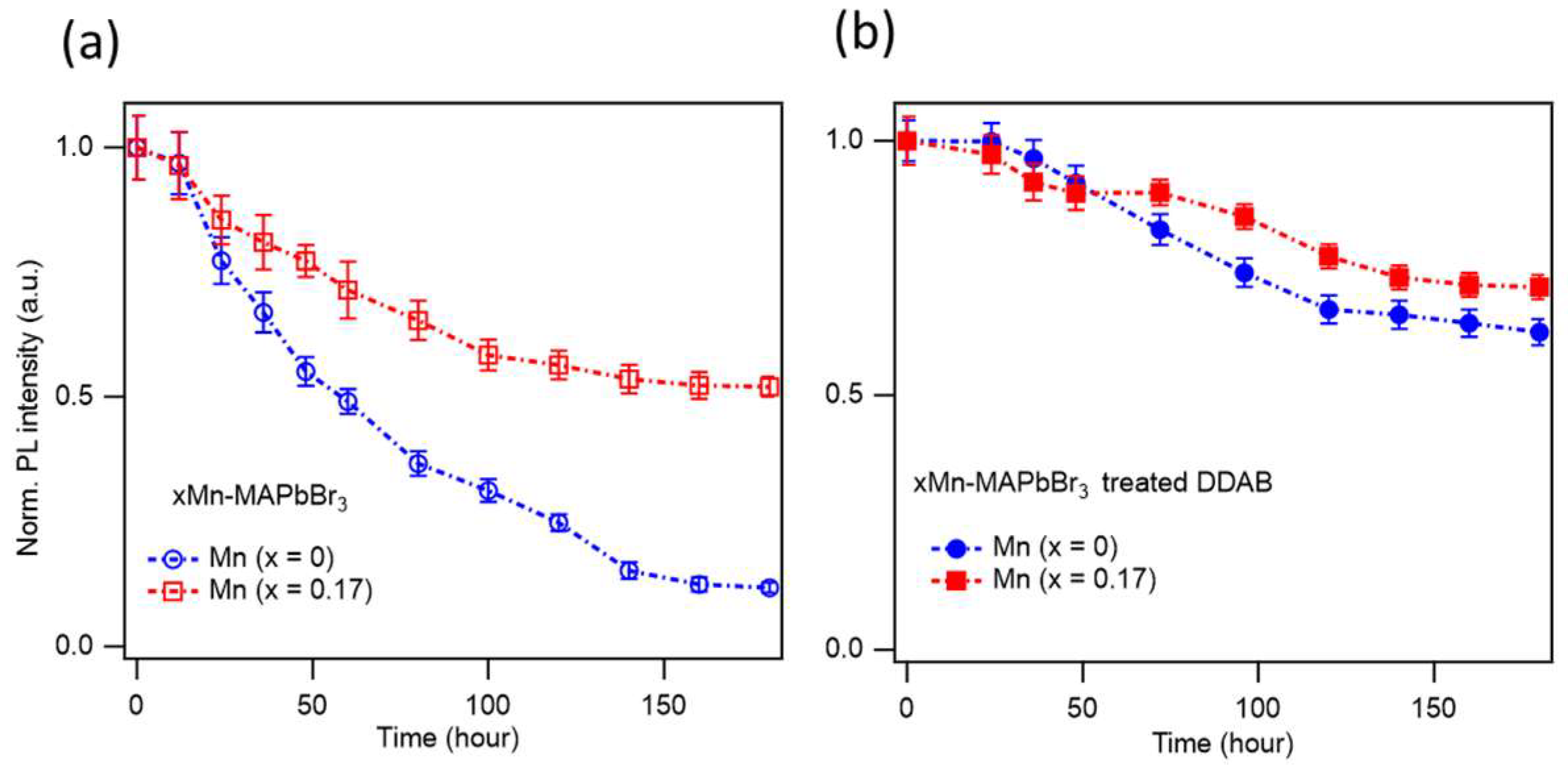

As discussed above, Mn²⁺ doping in MAPbBr₃ NCs enhances the PLQY by reducing non-radiative decay channels. Mn²⁺ doping also improves the long-term optical stability.

Figure 3 shows the PL stability of MAPbBr₃ NC films stored under ambient conditions over 180 hours. The as-synthesized xMn-MAPbBr₃ NCs exhibit PL intensity degradation, with the PL intensity retaining only 12% and 52% of the initial value for x = 0 and x = 0.17, respectively. This result indicates that Mn-doped perovskite NCs are significantly more stable than their undoped counterparts. To further enhance the optical stability, we treated the NCs with DDAB. After 180 hours under ambient conditions, the PL intensities of the DDAB treated NCs with x = 0 and x = 0.17 retained 62% and 72% of their original values, respectively, as shown in

Figure 3b. The DDA⁺ cations can replace the native oleic acid and oleylamine ligands on the NC surface or fill in missing ligands, thereby protecting the NCs from environmental factors such as humidity, oxidation, and other external degradation sources. Therefore, Mn²⁺ doping improves PLQY and the optical stability of MAPbBr₃ NCs by filling Pb²⁺ vacancies, passivating defects, reducing ion migration due to the stronger Mn–X bonds compared to Pb–X bonds, and enhancing the overall crystal robustness by minimizing lattice distortion.

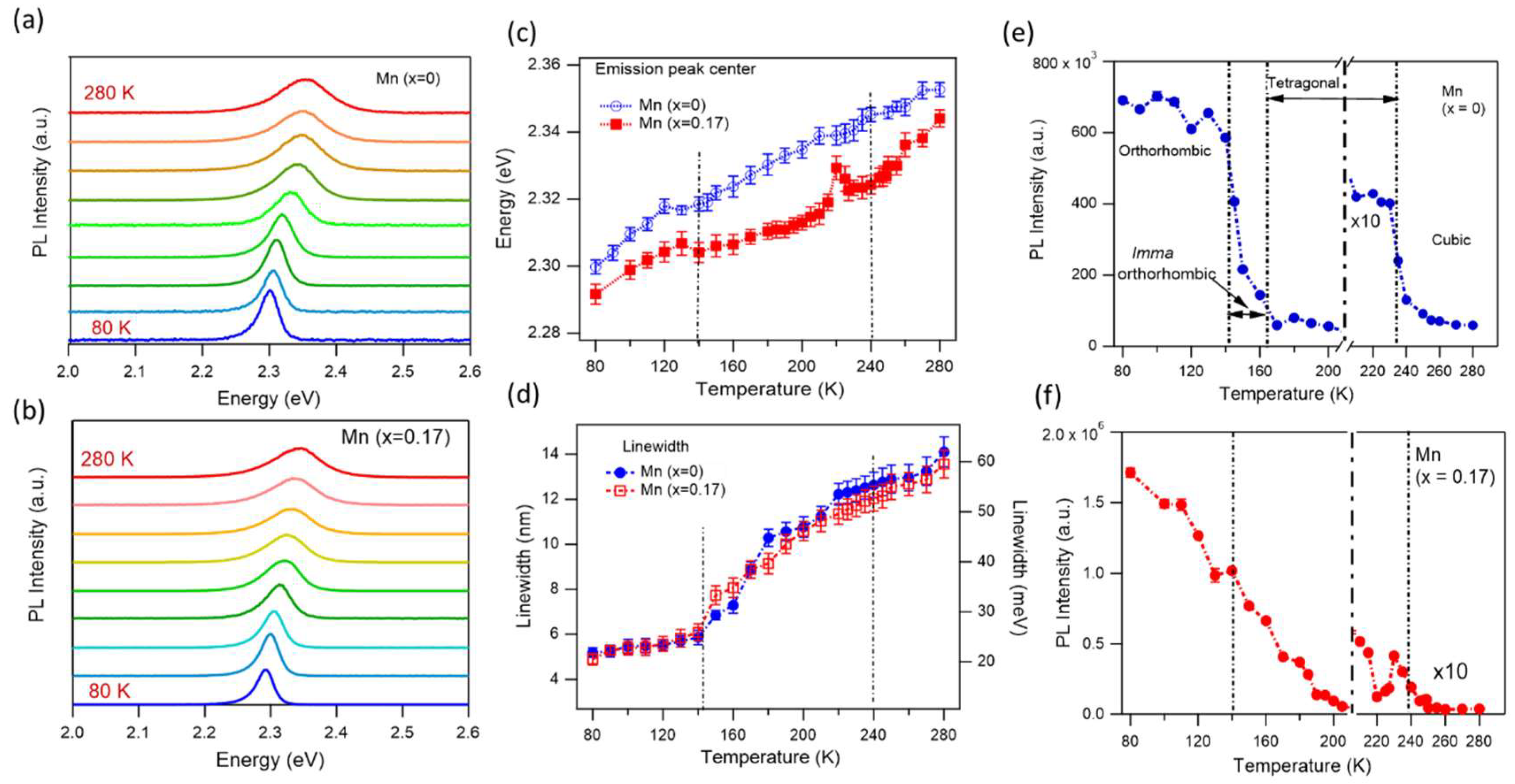

3.4. Optical Properties at Low Temperature and Crystal Phase Transitions

Incorporating Mn

2+ into MAPbBr

3 NCs may also affect the crystal structures, therefore affect crystallographic phases and phase transition temperatures. To investigate optical properties at different crystal phases, we perform PL spectra from 80 K to 280 K for two samples, non-doped and 17% Mn-doped NC. The latter case exhibits the highest PLQY for Mn-doped samples.

Figure 4 presents PL spectra, PL intensities, wavelengths, and linewidths of these two samples at different temperatures. Similar to previous observations in MHP NCs, the PL intensities decreased, the maximum PL peak blue shifted (emission energy increased), and the spectral linewidth broadened with increasing temperatures.

63,64 Notably, the observed blue shift of PL with increasing temperature is opposite to the typical behavior seen in conventional semiconductors, where lattice expansion generally leads to a red shift. In conventional semiconductors, the valence band maxima (VBM) and conduction band minima (CBM) arise from bonding and antibonding orbital pair, respectively. As temperature increases, thermal expansion causes the crystal lattice to dilate, resulting in a reduction in bandgap energy, which can be described by the Varshni equation.

65 In contrast, the electronic structure of MAPbBr₃ crystals is fundamentally different. The VBM originates from a strong antibonding interaction between the Pb 6s and Br 4p orbitals, while the CBM arises from an antibonding combination of the Pb 6p and Br 4s orbitals.

63,66,67 As the lattice expands with temperature, the VBM shifts downward in energy due to its antibonding nature (weakened antibonding interactions between atoms), whereas the CBM is relatively insensitive to lattice deformation. This asymmetry leads to an overall increase in the bandgap with temperature. Both undoped and doped MAPbBr₃ NCs exhibit similar temperature-dependent behavior. However, an anomalous behavior is observed in Mn-doped MAPbBr₃ at around 220 K, where a sharp blue shift is followed by a red shift at 227 K. This irregular trend coincides with a threefold drop in PL intensity in the same temperature range (

Figure 4f). This suggests a possible phase transition occurring near 220 K. Further investigation is needed to clarify the origin of this unusual bandgap and PL intensity behavior in Mn-doped MAPbBr₃ NCs in this temperature range.

The linewidth (obtained from Gaussian fits to the PL spectra) broadening observed with temperature originates from enhanced exciton-phonon interaction, as more phonons participate in the emission process at higher temperatures. Although both acoustic and longitudinal optical (LO) photons can contribute to homogeneous PL linewidth broadening, LO phonons have been reported as the dominant factor in perovskite NCs.

64 The temperature-dependent linewidth broadening is nearly identical for both undoped and Mn-doped MAPbBr₃ NCs (

Figure 4 d).

Figure 4 (e-f) presents the temperature-dependent PL intensities of the two samples. As the temperature increases, the PL intensities decrease due to enhanced NR recombination. At high temperatures, strong carrier–phonon interactions enable electrons or holes to acquire sufficient thermal energy to overcome potential barriers and transition into defect states, facilitating NR recombination. Conversely, at low temperatures, the MAPbBr

3 crystal structure becomes more ordered as the MA

+ cations, which rotate freely at room temperature, are immobilized. This structural ordering can lead to higher emission rates and narrower spectral linewidths. Moreover, when temperature changes across the crystallographic phase transitions, the relative alignment between excited carriers and trap energy levels shifts. As a result, we expect abrupt changes in PL intensity due to variations in NR activation across the phase transition points. It has been reported that bulk MAPbBr

3 perovskites exhibit three distinct crystallographic phases: below 144 K is the orthorhombic (

Pnma), between 144-237 K is the tetragonal phase (

I4/mcm), and above 237 K is the cubic phase (

Pmm).

68 However, there has been debate regarding a transient phase within the 148–155 K range, which has been attributed to phase coexistence.

69,70 More recently, Abia et al. employed neutron diffraction to sequentially analyze the crystallographic phase at this temperature range and identified the phase as orthorhombic

Imma.

71 MAPbBr

3 perovskites in nanostructured forms, such as NCs, are suggested to suppress noticeable phase transitions, likely due to their reduced crystal size, which inhibits structural transformation. As a result, no clear PL intensity change is typically observed across the known phase transition temperatures.

64 We speculate that the absence of distinct PL intensity change in NCs across the phase transition points arises from effective surface passivation with high PLQY, which minimizes the influence of defects or traps across different crystal phases. To see crystal transition phases, we intended to keep the sample in ambient conditions for one week before measurements, starting from low PLQY (see

Figure 3). It is clear to see the phase transition temperatures for non-doped MAPbBr

3 NCs,

Figure 4e. During the orthorhombic-to-tetragonal phase transition, the PL intensity decreases by nearly 80-fold. Within the

Imma orthorhombic phase (140-160K), the PL intensity gradually decreases. At the tetragonal-to-cubic transition (~135 K), the PL intensity drops by about fivefold. Within a single phase, the PL intensity remains relatively stable. In contrast, Mn-doped MAPbBr

3 NCs do not exhibit a clear orthorhombic-to-tetragonal phase transition, Instead, the PL intensity decreases steadily with increasing temperature. An anomalous change is observed at 220 K, accompanied by a corresponding shift in PL peak energy (see

Figure 4c). A sharp drop in PL intensity, approximately eightfold, occurs during the transition from the tetragonal to cubic phase. These results demonstrate that crystal phase transitions can be effectively tracked through temperature-dependent changes in PL intensity.

3.5. Superlattice Formation of xMn-MAPbBr3 NCs

NCs can self-assemble into highly ordered and periodic structures known as superlattices (SL). This artificial crystal-like arrangement facilitates inter-NC coupling, giving rise to emergent collective electronic, optical, or transport properties that are not present in uncoupled NCs. Most SLs reported to date have been formed using all-inorganic perovskite NCs, such as CsPbBr

3 synthesized via the hot-injection method, which yields high crystal quality and uniformity.

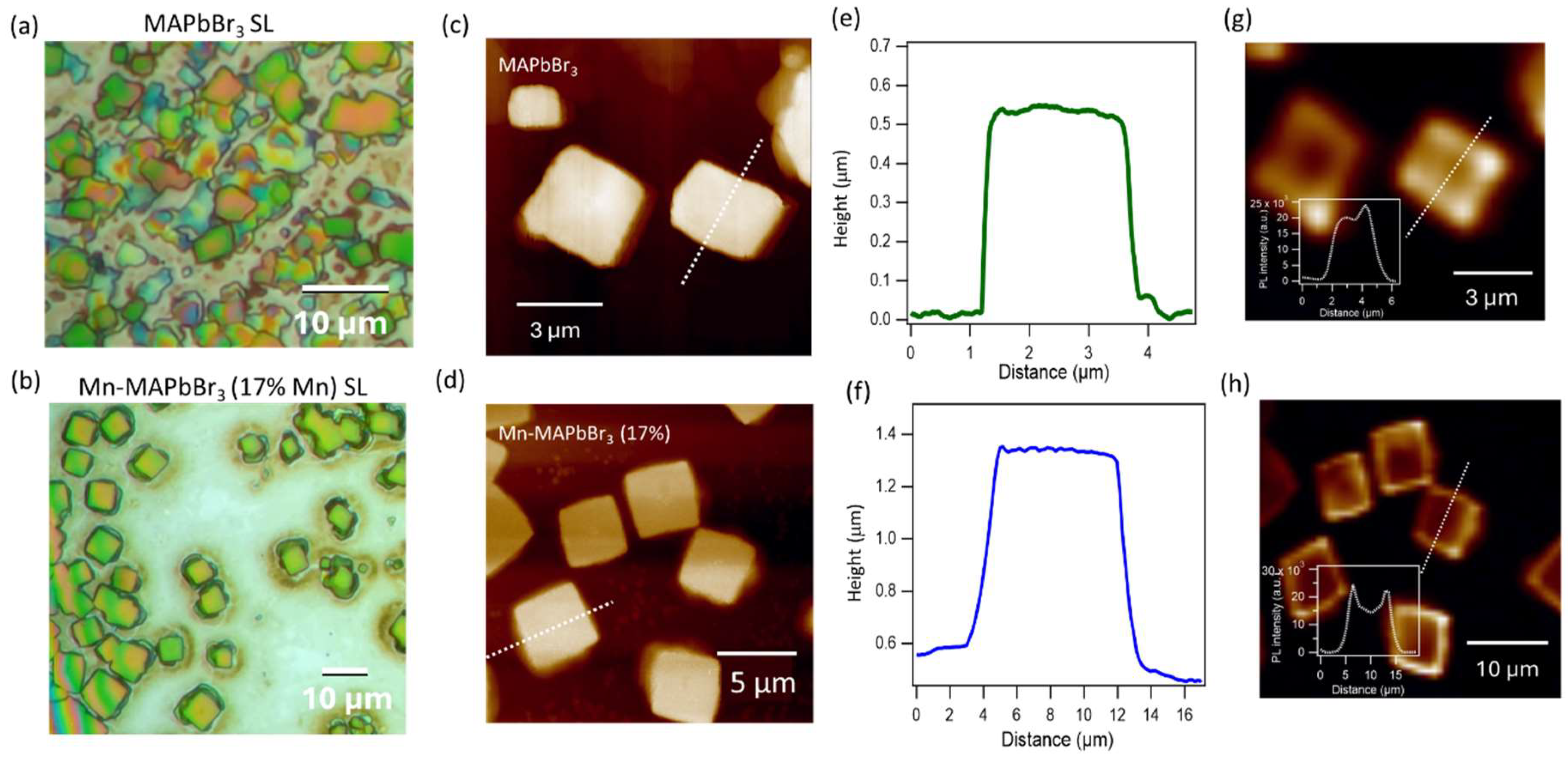

72 The formation of high-quality superlattices relies heavily on the NCs’ size and shape uniformity, as well as their surface chemistry. In contrast, hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites like MAPbBr₃, typically synthesized using the LARP method, often result in lower crystal quality and hence affect superlattice growth. However, as discussed above, Mn²⁺ doping in MAPbBr₃ has been shown to enhance NC quality, increase quantum yield, and improve material stability, factors that can promote the formation of higher-quality SLs. Furthermore, post-synthesis treatment with DDAB effectively passivates the NC surface, providing favorable conditions for self-assembly. In this study, we compared superlattice formation using pristine MAPbBr₃ NCs and Mn²⁺-doped MAPbBr₃ NCs (17% Mn²⁺), both treated with DDAB. Optical microscopy images (

Figure 5) reveal that Mn-doped NCs form well-defined SLs with a regular square shape, larger SL sizes (7–9 µm vs. 2–4 µm for the non-doped NCs), higher uniformity, and clearer backgrounds. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) shows SLs from pristine NCs have dimensions of ~3 µm in size and ~0.55 µm in thickness, whereas SLs from Mn-doped NCs reach ~8 µm in size and ~0.8 µm in thickness. Additionally, the surface of Mn-doped SLs is noticeably flatter. Two-photon fluorescence (2PF) imaging, performed using a femtosecond laser with 800 nm excitation, maps the PL distribution within the SLs (

Figure 5 g,h). Notably, 2PF intensities are higher localized at the edges of the Mn-doped SLs, which may indicate improved surface passivation at the edge surfaces.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that controlled Mn²⁺ doping in MAPbBr3 NCs significantly enhances their optical performance and structural stability. Mn²⁺ ions are successfully incorporated into the perovskite lattice at concentrations up to 25%, inducing lattice contraction without compromising the crystal integrity or optical properties. This doping results in a notable increase in photoluminescence quantum yield, reaching a maximum of 72% at 17% Mn2+ doping, and a reduction in non-radiative recombination, as confirmed by PL dynamics and time-resolved measurements. Mn²⁺ doping also improves the ambient optical stability of the NCs, which is further enhanced by surface passivation using DDAB. Temperature-dependent PL studies reveal both conventional and anomalous emission behaviors in the Mn-doped samples. Structurally, Mn²⁺ doping enhances the robustness of MAPbBr3 by filling vacancies and trap states and substituting Pb²⁺ sites without disrupting the lattice framework. Moreover, Mn²⁺ incorporation promotes the self-assembly of MAPbBr3 NCs into superlattice structures, leading to larger nanocrystals and improved crystallinity. These findings offer valuable insights into the role of transition-metal doping in tuning the optical and structural properties of perovskite NCs, paving the way for the development of doped perovskites with improved functionality for lighting and optoelectronic applications.

Author Contributions

M.T.T conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. T.T.T.P. synthesized materials, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.T.K.N and T.K.M contributed to the materials synthesis and characterizations. All authors discussed and contributed to the scientific results and the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hassan, Y.; Song, Y.; Pensack, R. D.; Abdelrahman, A. I.; Kobayashi, Y.; Winnik, M. A.; Scholes, G. D. Structure-Tuned Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgras, V.; Tominaka, S.; Ryan, J. W.; Henzie, J.; Takei, T.; Ohara, K.; Yamauchi, Y. Observation of Quantum Confinement in Monodisperse Methylammonium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals Embedded in Mesoporous Silica. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138, 13874–13881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droseros, N.; Longo, G.; Brauer, J. C.; Sessolo, M.; Bolink, H. J.; Banerji, N. Origin of the Enhanced Photoluminescence Quantum Yield in MAPbBr3 Perovskite with Reduced Crystal Size. ACS Energy Lett 2018, 3, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Boehme, S. C.; Feld, L. G.; Moskalenko, A.; Dirin, D. N.; Mahrt, R. F.; Stöferle, T.; Bodnarchuk, M. I.; Efros, A. L.; Sercel, P. C.; Kovalenko, M. V.; Rainò, G. Single-Photon Superradiance in Individual Caesium Lead Halide Quantum Dots. Nature 2024, 626, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Kido, J. Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots for Light-Emitting Devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 11868–11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Chou, S.-Y.; Huang, P.; Xiao, C.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, F.; Huang, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhong, H.; Sun, H.-B.; Pei, Q. Stretchable Organometal-Halide-Perovskite Quantum-Dot Light-Emitting Diodes. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1807516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Liu, X.; Qiu, R.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, C.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, H. Enhanced UV-C Detection of Perovskite Photodetector Arrays via Inorganic CsPbBr3 Quantum Dot Down-Conversion Layer. Adv Opt Mater 2019, 7, 1801812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, R.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, X. Inhibiting Lattice Distortion of CsPbI 3 Perovskite Quantum Dots for Solar Cells with Efficiency over 16.6%. Energy Environ Sci 2022, 15, 4201–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Chen, J.; Qiu, J.; Ma, H.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Tailoring Solvent-Mediated Ligand Exchange for CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dot Solar Cells with Efficiency Exceeding 16.5%. Joule 2022, 6, 1632–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, R.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, R.; Hua, Y. Antisolvent-Assisted In Situ Cation Exchange of Perovskite Quantum Dots for Efficient Solar Cells. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2212160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Zou, C.; Mao, C.; Corp, K. L.; Yao, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-J.; Schlenker, C. W.; Jen, A. K. Y.; Lin, L. Y. CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dot Vertical Cavity Lasers with Low Threshold and High Stability. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-J.; Dai, J.-H.; Lin, J.-D.; Mo, T.-S.; Lin, H.-P.; Yeh, H.-C.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Jiang, S.-A.; Lee, C.-R. Wavelength-Tunable and Highly Stable Perovskite-Quantum-Dot-Doped Lasers with Liquid Crystal Lasing Cavities. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 33307–33315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzat, H.; Sun, W.; Kaplan, A. E. K.; Krieg, F.; Ginterseder, M.; Spokoyny, B.; Klein, N. D.; Shulenberger, K. E.; Perkinson, C. F.; Kovalenko, M. V.; Bawendi, M. G. Coherent Single-Photon Emission from Colloidal Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots. Science (1979) 2019, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Marczak, M.; Feld, L.; Boehme, S. C.; Bernasconi, C.; Moskalenko, A.; Cherniukh, I.; Dirin, D.; Bodnarchuk, M. I.; Kovalenko, M. V.; Raino, G. Room-Temperature, Highly Pure Single-Photon Sources from All-Inorganic Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots. Nano Lett 2022, 22, 3751–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakosyan, A.; Yun, S.; Yoon, S.-G.; Choi, J. Surface Engineering for Improved Stability of CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosconi, E.; Umari, P.; De Angelis, F. Electronic and Optical Properties of MAPbX3 Perovskites (X = I, Br, Cl): A Unified DFT and GW Theoretical Analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 27158–27164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.-W.; Hsu, B.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lee, C.-A.; Liu, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-F.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wu, T.-L.; Manikandan, A.; Ho, R.-M.; Tsao, C.-S.; Cheng, C.-H.; Chueh, Y.-L.; Lin, H.-W. Perovskite Quantum Dots with Near Unity Solution and Neat-Film Photoluminescent Quantum Yield by Novel Spray Synthesis. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1705532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Vickers, E. T.; Rao, L.; Lindley, S. A.; Allen, A. C.; Luo, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Z. Synergistic Surface Passivation of CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots with Phosphonic Acid and (3-Aminopropyl)Triethoxysilane. Chemistry – A European Journal 2019, 25, 5014–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, G. H.; Yin, J.; Bakr, O. M.; Mohammed, O. F. Successes and Challenges of Core/Shell Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett 2021, 6, 1340–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Alam, F.; Shamsi, J.; Abdi-Jalebi, M. Doping Up the Light: A Review of A/B-Site Doping in Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals for Next-Generation LEDs. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024, 128, 10084–10107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciarelli, D.; Meggiolaro, D.; Belanzoni, P.; Alothman, A. A.; Mosconi, E.; De Angelis, F. Energy vs Charge Transfer in Manganese-Doped Lead Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett 2021, 6, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, B.; Reyes-Castillo, D. T.; Coutino-Gonzalez, E.; Sánchez-Aké, C.; Ramos, C.; Falcony, C.; Solis-Ibarra, D. Enhanced Luminescence and Mechanistic Studies on Layered Double-Perovskite Phosphors: Cs4Cd1- XMnxBi2Cl12. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 9307–9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liao, W. Q.; Tang, Y. Y.; Li, P. F.; Shi, P. P.; Cai, H.; Xiong, R. G. Discovery of an Antiperovskite Ferroelectric in [(CH 3 ) 3 NH] 3 (MnBr 3 )(MnBr 4 ). J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 8110–8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, L. Fe2+ Doped in CsPbCl3 Perovskite Nanocrystals: Impact on the Luminescence and Magnetic Properties. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 33017–33022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, S. M.; Wobben, M.; Ehrler, B. Rare-Earth Quantum Cutting in Metal Halide Perovskites-a Review. Materials Horizons 2021, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Artizzu, F.; Liu, J.; Singh, S.; Locardi, F.; Mara, D.; Hens, Z.; Van Deun, R. Boosting the Er3+1.5 Μm Luminescence in CsPbCl3Perovskite Nanocrystals for Photonic Devices Operating at Telecommunication Wavelengths. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2020, 3, 4699–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Song, S.; Lv, P.; Li, J.; Cao, B.; Liu, Z. Thermally Stable Rare-Earth Eu3+-Doped CsPbCl3 Perovskite Quantum Dots with Controllable Blue Emission. J Lumin 2023, 260, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstein, T. J.; Kroupa, D. M.; Gamelin, D. R. Picosecond Quantum Cutting Generates Photoluminescence Quantum Yields Over 100% in Ytterbium-Doped CsPbCl3 Nanocrystals. Nano Lett 2018, 18, 3792–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupa, D. M.; Roh, J. Y.; Milstein, T. J.; Creutz, S. E.; Gamelin, D. R. Quantum-Cutting Ytterbium-Doped CsPb(Cl1–XBrx)3 Perovskite Thin Films with Photoluminescence Quantum Yields over 190%. ACS Energy Lett 2018, 3, 2390–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Fabbri, E.; Abbott, D. F.; Cheng, X.; Clark, A. H.; Nachtegaal, M.; Borlaf, M.; Castelli, I. E.; Graule, T.; Schmidt, T. J. Functional Role of Fe-Doping in Co-Based Perovskite Oxide Catalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 5231–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Bai, X.; Yang, D.; Chen, X.; Jing, P.; Qu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, J.; Xu, W.; Dong, B.; Song, H. Doping Lanthanide into Perovskite Nanocrystals: Highly Improved and Expanded Optical Properties. Nano Lett 2017, 17, 8005–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Fan, J.; Chen, B.; Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Deng, R.; Liu, X. Rare-Earth Doping in Nanostructured Inorganic Materials. Chem Rev 2022, 122, 5519–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Vickers, E. T.; Luo, B.; Allen, A. C.; Chen, E.; Roseman, G.; Wang, Q.; Kliger, D. S.; Millhauser, G. L.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Z. First Synthesis of Mn-Doped Cesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Magic Sized Clusters at Room Temperature. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2020, 11, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Q.; Liu, M. L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pan, C. Y. Mn2+ Doped CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots with High Quantum Yield and Stability for Flexible Array Displays. J Solid State Chem 2023, 327, 124295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parobek, D.; Roman, B. J.; Dong, Y.; Jin, H.; Lee, E.; Sheldon, M.; Son, D. H. Exciton-to-Dopant Energy Transfer in Mn-Doped Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Nano Lett 2016, 16, 7376–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, W.; Liang, D.; Zheng, B.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Zhu, C.; Lin, L.; Zhu, X.; Duan, H.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Pan, A. Magnetic Doping Induced Strong Circularly Polarized Light Emission and Detection in 2D Layered Halide Perovskite. Adv Opt Mater 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guria, A. K.; Dutta, S. K.; Adhikari, S. Das; Pradhan, N. Doping Mn2+ in Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Successes and Challenges. ACS Energy Lett 2017, 2, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Qiao, B.; Xu, Z.; Song, D.; Song, P.; Liang, Z.; Shen, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S. Postsynthetic, Reversible Cation Exchange between Pb2+ and Mn2+ in Cesium Lead Chloride Perovskite Nanocrystals. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 20387–20395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.; Glover, E. N. K.; Bronstein, H.; Scanlon, D. O.; Palgrave, R. G. On the Application of the Tolerance Factor to Inorganic and Hybrid Halide Perovskites: A Revised System. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 4548–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, J. S.; Christians, J. A.; Kamat, P. V. Intriguing Optoelectronic Properties of Metal Halide Perovskites. Chem Rev 2016, 116, 12956–13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lin, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, K.; Robel, I.; Pietryga, J. M.; Klimov, V. I. Mn2+-Doped Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals with Dual-Color Emission Controlled by Halide Content. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138, 14954–14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Zhou, S.; Fang, G.; Chen, X.; Zhong, J. Fast Room-Temperature Cation Exchange Synthesis of Mn-Doped CsPbCl3 Nanocrystals Driven by Dynamic Halogen Exchange. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 39872–39878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parobek, D.; Roman, B. J.; Dong, Y.; Jin, H.; Lee, E.; Sheldon, M.; Son, D. H. Exciton-to-Dopant Energy Transfer in Mn-Doped Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Nano Lett 2016, 16, 7376–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Tian, F.; Huang, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, D. Chlorine-Additive-Promoted Incorporation of Mn2+ Dopants into CsPbCl3 Perovskite Nanocrystals. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 12465–12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Zong, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, C.; Cui, Y. Postsynthetic Doping of MnCl2 Molecules into Preformed CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals via a Halide Exchange-Driven Cation Exchange. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1700095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, S. C.; Bodnarchuk, M. I.; Burian, M.; Bertolotti, F.; Cherniukh, I.; Bernasconi, C.; Zhu, C.; Erni, R.; Amenitsch, H.; Naumenko, D.; Andrusiv, H.; Semkiv, N.; John, R. A.; Baldwin, A.; Galkowski, K.; Masciocchi, N.; Stranks, S. D.; Rainò, G.; Guagliardi, A.; Kovalenko, M. V. Strongly Confined CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots as Quantum Emitters and Building Blocks for Rhombic Superlattices. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, C. J.; Sutton, C.; Goldsmith, B. R.; Ouyang, R.; Musgrave, C. B.; Ghiringhelli, L. M.; Scheffler, M. New Tolerance Factor to Predict the Stability of Perovskite Oxides and Halides. Sci Adv 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Adinolfi, V.; Comin, R.; Yuan, M.; Alarousu, E.; Buin, A.; Chen, Y.; Hoogland, S.; Rothenberger, A.; Katsiev, K.; Losovyj, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dowben, P. A.; Mohammed, O. F.; Sargent, E. H.; Bakr, O. M. Low Trap-State Density and Long Carrier Diffusion in Organolead Trihalide Perovskite Single Crystals. Science (1979) 2015, 347, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidaminov, M. I.; Abdelhady, A. L.; Murali, B.; Alarousu, E.; Burlakov, V. M.; Peng, W.; Dursun, I.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; MacUlan, G.; Goriely, A.; Wu, T.; Mohammed, O. F.; Bakr, O. M. High-Quality Bulk Hybrid Perovskite Single Crystals within Minutes by Inverse Temperature Crystallization. Nature Communications 2015 6:1 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Bakthavatsalam, R.; Kundu, J. Efficient Exciton to Dopant Energy Transfer in Mn2+-Doped (C4H9NH3)2PbBr4 Two-Dimensional (2D) Layered Perovskites. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 7816–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Jiang, X.; Molokeev, M.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Xia, Z. Optically Modulated Ultra-Broad-Band Warm White Emission in Mn2+-Doped (C6H18N2O2)PbBr4 Hybrid Metal Halide Phosphor. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 5788–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Behera, R. K.; Deb, S.; Baitalik, S.; Pradhan, N. Doping Mn(II) in All-Inorganic Ruddlesden–Popper Phase of Tetragonal Cs2PbCl2I2 Perovskite Nanoplatelets. J Phys Chem Lett 2019, 10, 1954–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirberger, M.; Yang, J. J. Structural Differences Between Pb2+- and Ca2+-Binding Sites in Proteins: Implications with Respect to Toxicity. J Inorg Biochem 2008, 102, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, S. Y.; Liu, C. M.; Liaw, L. J.; Som, S.; Mohapatra, A.; Sankar, R.; Lin, W. C.; Chao, Y. C. Impact of Co2+ on the Magneto-Optical Response of MAPbBr3: An Inspective Study of Doping and Quantum Confinement Effect. Materials Today Physics 2022, 27, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moj, K.; Owsiński, R.; Robak, G.; Gupta, M. K.; Scholz, S.; Mehta, H. Measurement of Precision and Quality Characteristics of Lattice Structures in Metal-Based Additive Manufacturing Using Computer Tomography Analysis. Measurement 2024, 231, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M. C.; Pan, C. Y. Research on the Stability of Luminescence of CsPbBr3 and Mn:CsPbBr3 PQDs in Polar Solution. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 15420–15426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C. C.; Xu, K. Y.; Wang, D.; Meijerink, A. Luminescent Manganese-Doped CsPbCl3 Perovskite Quantum Dots. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Matras-Postolek, K.; Yang, P. Ion Exchange Derived CsPbBr3:Mn Nanocrystals with Stable and Bright Luminescence towards White Light-Emitting Diodes. Mater Res Bull 2022, 153, 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Du, L. Investigation for Structural and Electronic Properties of Mn-Doped Perovskite at Different Doping Concentrations. Comput Mater Sci 2025, 252, 113782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; An, J.; Katayama, T.; Duan, M.; Shi, X. P.; Wang, Y.; Furube, A. Photogenerated Carrier Dynamics of Mn2+ Doped CsPbBr3 Assembled with TiO2 Systems: Effect of Mn Doping Content. Journal of Chemical Physics 2024, 160, 164713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, C. T.; Minh, D. N.; Ahn, K. J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K. G. Verification of Type-A and Type-B-HC Blinking Mechanisms of Organic–Inorganic Formamidinium Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots by FLID Measurements. Scientific Reports 2020 10:1 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Yin, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C.; Yu, W. W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, M. Slow Auger Recombination of Charged Excitons in Nonblinking Perovskite Nanocrystals without Spectral Diffusion. Nano Lett 2016, 16, 6425–6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. M.; Moon, C. J.; Lim, H.; Lee, Y.; Choi, M. Y.; Bang, J. Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: Splitting of the Photoluminescence Peaks of CsPbBr3 and CsPb(Br/I)3 Quantum Dots at Low Temperature. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 26054–26062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H. C.; Choi, J. W.; Shin, J.; Chin, S. H.; Ann, M. H.; Lee, C. L. Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence of CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots and Bulk Counterparts. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2018, 9, 4066–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshni, Y. P. Temperature Dependence of the Energy Gap in Semiconductors. Physica 1967, 34, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, S.; Palermo, G.; Ashari-Astani, N.; Grätzel, M.; Grätzel, G.; Rothlisberger, U. Valence and Conduction Band Tuning in Halide Perovskites for Solar Cell Applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, J. S.; Christians, J. A.; Kamat, P. V. Intriguing Optoelectronic Properties of Metal Halide Perovskites. 2016. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12956–13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Kim, J. S.; Lee, T. W. Structural and Thermal Disorder of Solution-Processed CH3NH3PbBr3 Hybrid Perovskite Thin Films. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9, 10344–10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ming, W.; Du, M.-H.; Keum, J. K.; Puretzky, A. A.; Rouleau, C. M.; Huang, J.; Geohegan, D. B.; Wang, X.; Xiao, K.; Perovskites Yang, O. B.; Yang, B.; Keum, J. K.; Puretzky, A. A.; Rouleau, C. M.; Geohegan, D. B.; Xiao, K.; Ming, W.; Du, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, J. Real-Time Observation of Order-Disorder Transformation of Organic Cations Induced Phase Transition and Anomalous Photoluminescence in Hybrid Perovskites. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1705801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C. A.; Martínez-Huerta, M. V.; Alvarez-Galván, M. C.; Kayser, P.; Gant, P.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Fernández-Díaz, M. T.; Fauth, F.; Alonso, J. A. Elucidating the Methylammonium (MA) Conformation in MAPbBr3 Perovskite with Application in Solar Cells. Inorg Chem 2017, 56, 14214–14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abia, C.; López, C. A.; Cañadillas-Delgado, L.; Fernández-Diaz, M. T.; Alonso, J. A. Crystal Structure Thermal Evolution and Novel Orthorhombic Phase of Methylammonium Lead Bromide, CH3NH3PbBr3. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainò, G.; Becker, M. A.; Bodnarchuk, M. I.; Mahrt, R. F.; Kovalenko, M. V.; Stöferle, T. Superfluorescence from Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dot Superlattices. Nature 2018 563:7733 2018, 563, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).