1. Introduction

Child health is a fundamental pillar for Ecuador’s development. Despite advancements in public health, challenges such as chronic malnutrition persist, affecting twenty-three percent of children under 5 years old, according to INEC in 2023 [

1] as well as non-compliance with vaccination schedules. Access to quality medical care and adequate follow-up are crucial to addressing these issues [

2]. The lack of digital tools in many health centers hinders the recording, tracking, and management of information, which can impact the quality of care [

3]. Nutrition and immunization play a vital role in children’s lives from their earliest months. Inadequate nutrition at home negatively affects a child’s health, learning, and development [

4]. On the other hand, vaccines save 2 to 3 million lives each year by protecting children from serious diseases [

5]. Monitoring both aspects is essential to ensuring optimal child development. To address these challenges, this retrospective cohort study will examine the feasibility and impact of implementing a digital system for the anthropometric and nutritional monitoring of children in Ecuador [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

In today’s rapidly evolving society, the need for effective tools to monitor the physical and mental well-being of children and adolescents has become increasingly urgent. In Ecuador, a country facing rising rates of childhood obesity and malnutrition [

7], the development of innovative solutions to track and address these pressing health concerns is of utmost importance. Medical centers in the south of Guayaquil encountered difficulties in recording, tracking, and managing nutritional and immunological information for patients [

8]. We implemented a web and mobile system to automate these processes. We utilized open-source technologies, including PHP for web development, Android Studio for the mobile application, and MySQL for database management, to ensure the system’s accessibility and adaptability. We hypothesized that using the Web System would strengthen nutritional control. As a result, this study looked at how parents felt about nutritional monitoring and control [

9]. It found that the system was much better than traditional methods at collecting accurate data, finding nutritional problems early, and making clinical decisions [

10]. We used the Extreme Programming (XP) software development methodology, which emphasizes the continuous delivery of functional software and close client collaboration. XP enabled rapid adaptation to changing requirements and an efficient response to the clinics needs. The use of this methodology facilitated communication and collaboration between developers and clinic staff, ensuring that the system met the end users’ requirements and expectations.

2.1. Web System

The system has essential modules: The Nutritional Control module enables the documentation of children’s anthropometric measurements (weight, height, circumferences) during each appointment and automatically assigns a diagnosis according to the growth percentiles set by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

11]. The approach evaluates the child’s body measurements by comparing them to established reference standards and assessing whether they are within the appropriate ranges for their age and gender. Furthermore, it provides individualized dietary suggestions based on the child’s nutritional condition, encouraging appropriate and nutritious eating practices [

12]. This module’s significance lies in its ability to identify and mitigate malnutrition or overweight problems in children, thereby promoting their ideal growth and development.The Immunization Tracking module oversees the documentation of immunizations given to each child, including the date of administration, vaccine type, batch number, and the name of the administering practitioner. Furthermore, the system calculates and presents the additional vaccination doses required by the child according to the national immunization schedule [

13]. Furthermore, it sends automated notifications to parents of impending vaccinations, thereby encouraging compliance with the immunization timetable and contributing to disease prevention. We conducted functionality and usability tests based on the ISO/IEC 9126 standard to evaluate the system’s quality. These tests included verifying that all system functionalities operated correctly, such as data recording, report generation, and reminder sending. We also evaluated the system’s user-friendliness for doctors and parents, considering elements like unambiguous instructions, user-friendly navigation, and compatibility with different devices. We used the results of these tests to identify and correct errors, thereby enhancing the user experience. We also administered surveys to doctors and parents to gather their perceptions of the system. We evaluated aspects such as ease of use, utility of the tools, and overall satisfaction with the system. The surveys provided valuable information about user experiences and needs, which contributed to improving the system and adapting it to meet end users’ expectations [

14]. The study included 453 parents of children aged 0 months to 12 years living in the southern sector of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Local health centers, which regularly monitor child growth, selected all participants. We excluded parents whose children suffered from severe chronic illnesses or had incomplete data. The study ensured equitable gender representation, with a focus on comparing urban and rural areas, and collected data on the parents’ socioeconomic and educational levels.

3. Algorithm and Implementation

To classify the nutritional status of the children, we categorized their nutritional state based on anthropometric measurements such as height [

15], weight, and age. The system enabled us to calculate indices such as BMI-for-age, weight-for-height, and height-for-age, and then classify these according to standard growth charts or WHO guidelines.

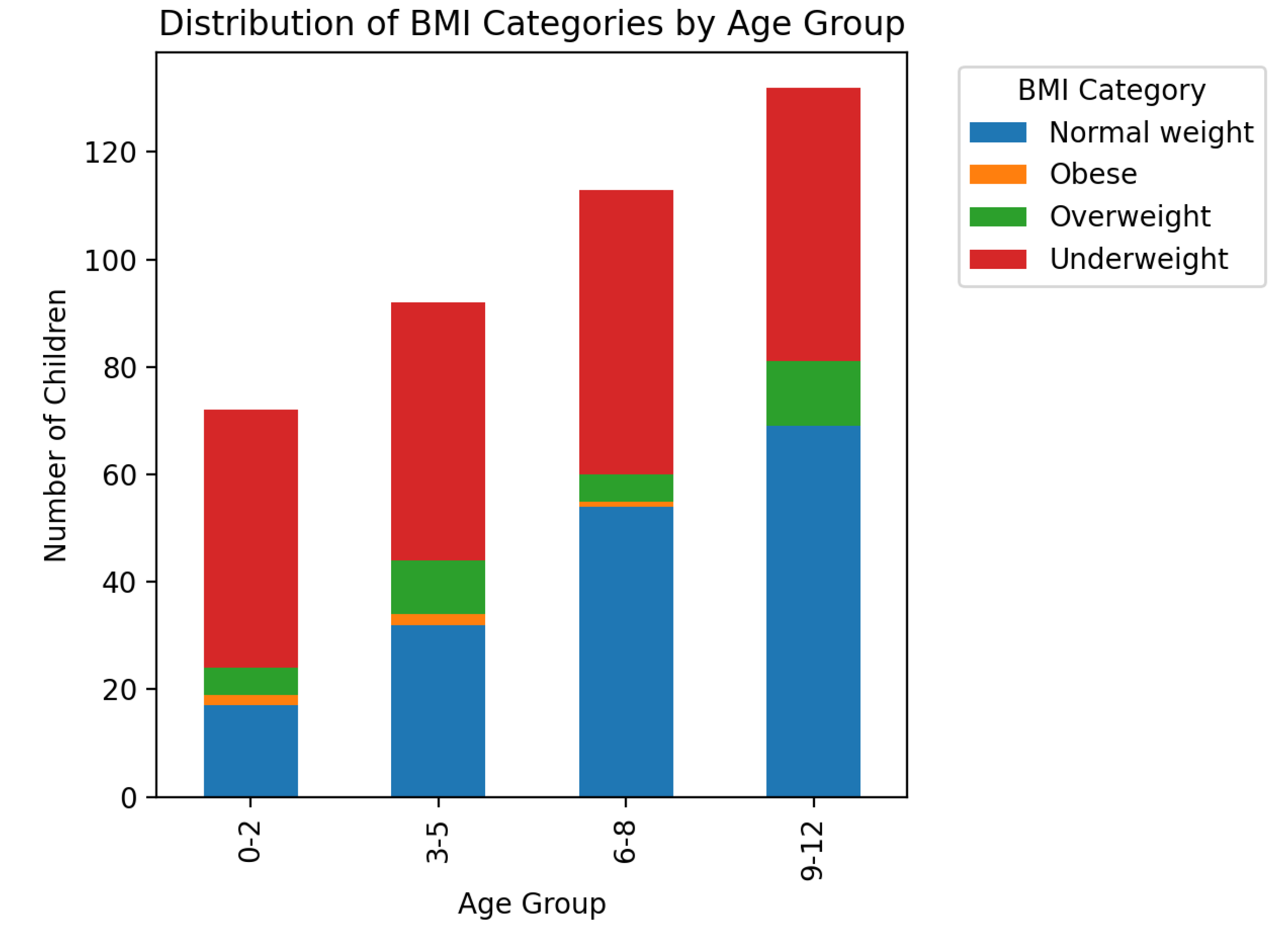

During the cohort analysis, we defined specific groups based on common characteristics and monitored their progress over time. In this case, we grouped the children by age ranges and their initial nutritional status (based on BMI). This approach allowed us to observe trends and changes in their nutritional status, facilitating early intervention and tailored recommendations for each group. We evaluated whether there were significant differences in BMI based on the frequency of medical attendance using ANOVA analysis, which used BMI as the dependent variable and the frequency of medical visits as the independent variable. This section includes the distribution of BMI, categories by age group (

Figure 1),.

F-Statistic: 1.178 p-value (PR(>F)): 0.319

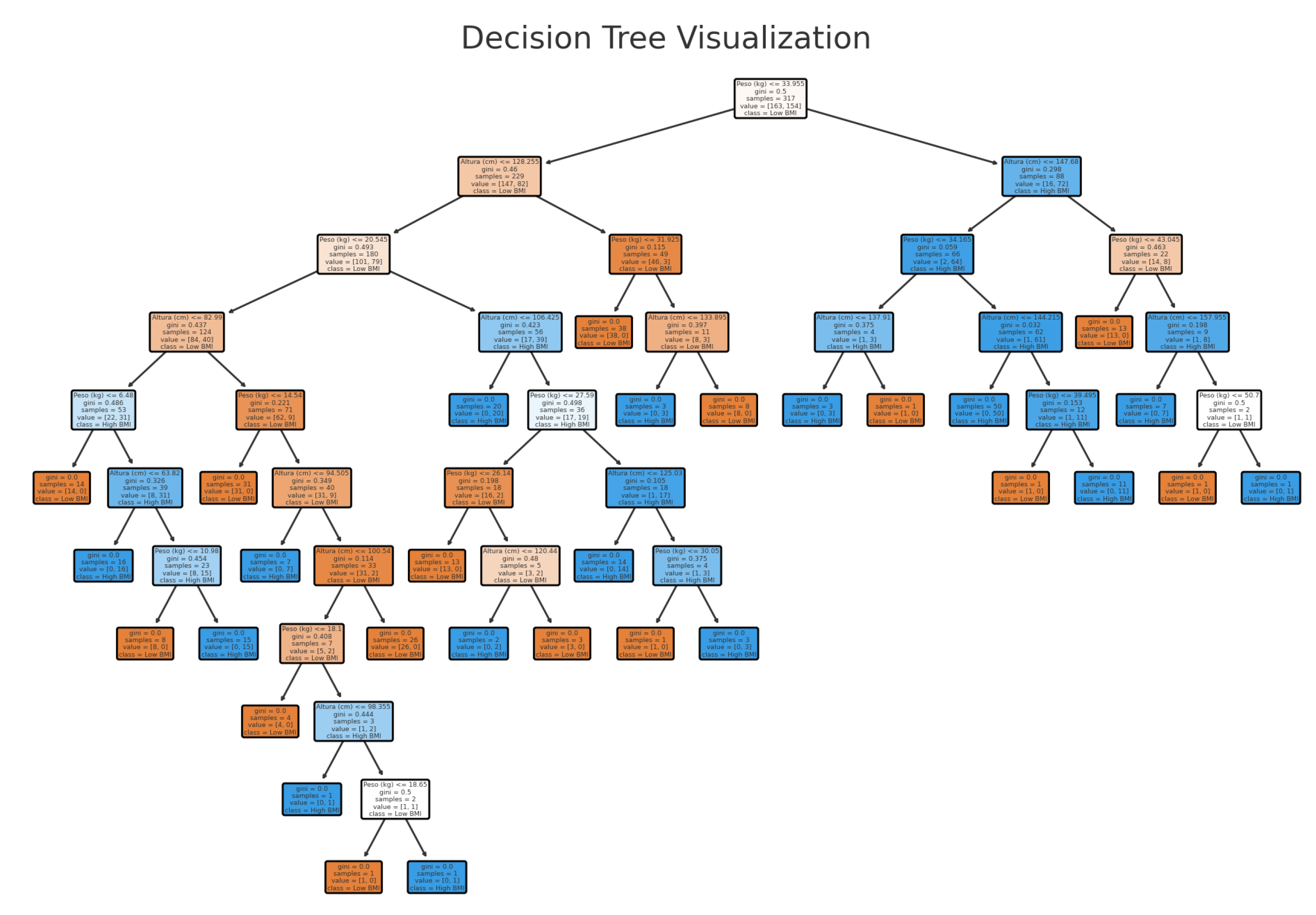

This analysis did not reveal significant differences in BMI according to the frequency of medical visits. Therefore, we used a decision tree model to classify body mass index (BMI) levels in children, using age, weight, height, and gender as predictive variables. The decision tree illustrates the application of decision rules to classify BMI as either "low BMI" or "high BMI." Each node represents a decision based on a characteristic, and the tree splits the data at each node to maximize class separation. We evaluated entropy to measure the degree of disorder or impurity of the data set by running the decision tree algorithm. We calculated the entropy for a data set that had proportions of children with high BMI(p) and children with low BMI(q), Eq.

1.

We used the Gini index to measure the probability of incorrect classification of an element based on the class distribution at the node. The split in the decision tree selects the feature that minimizes the Gini impurity or maximizes the information gain. If we generate a random prediction, we use the following equation to determine this measure:Eq.

2.

A was obtained an Accuracy: 92.65 percent.This indicates that the decision tree correctly classified the BMI category for approximately 93 percent of the test data. The F1 Score shows that precision and recall are balanced at 93 percent for both classes. The model performs well, with high accuracy, balanced precision, and recall across both BMI categories. Decision trees are relatively robust against missing data and noise in the data (

Figure 2).

In observational studies like this one, it is common to encounter incomplete data or some variability in measurements. Decision trees can handle these imperfections by hierarchically splitting the data and making decisions based on the most discriminate variables at each node. The confusion matrix shows the following results:

True Positives (High BMI): 63 True Negatives (Low BMI): 63 False Positives (Low BMI incorrectly classified as High BMI): 2 False Negatives: 8 (High BMI incorrectly classified as Low BMI)

The high number of true positives (TP) suggests that the model is effective at identifying cases of high BMI. The low number of false positives indicates that the model rarely classifies low BMI cases as high BMI cases. The described methodology not only offers a robust framework for analyzing nutritional and anthropometric data, but it can also seamlessly integrate into Ecuador’s web system. This integration facilitates a continuous cycle of data collection, analysis, feedback, and adjustment, enhancing the ability of professionals to monitor and respond to child health needs in real time.

4. Results

The integration of mobile health (mHealth) technologies into pediatric care has the potential to streamline healthcare delivery and improve patient outcomes. The system proved effective in automating clinic processes, significantly improving efficiency and access to information [

16]. Doctors reported a 50 percent reduction in time spent on administrative tasks, such as patient registration and appointment scheduling, thereby freeing up more time for direct patient care. Additionally, the quick and simple access to patients’ complete medical histories enabled doctors to make more informed decisions and provide more personalized, high-quality care [

17].

A particularly valuable feature was the integration of a nutritional module that calculates daily caloric needs based on the patient’s sex, age, and weight status, and distributes them across meals according to clinical guidelines. This functionality supported precise dietary planning for children with nutritional risks (e.g., underweight or overweight), and offered caregivers practical, evidence-based recommendations on meal distribution, enhancing adherence to nutritional guidance.

Importantly, the software was developed entirely using free and open-source technologies—including PHP, Android Studio, and MySQL—which ensured scalability, adaptability, and cost-efficiency. Moreover, the system was deployed and made available to participating health centers at no cost, reinforcing its value as a sustainable and accessible digital health solution in resource-constrained environments.

Parents expressed high satisfaction with the platform, with 95 percent rating the ease of use of the mobile application as “very good” or “excellent.” Furthermore, 85 percent appreciated functionalities such as online appointment scheduling, automated vaccination reminders, and detailed access to nutritional and immunization data.

Usability tests and satisfaction surveys confirmed that the system meets the quality criteria defined by the ISO/IEC 9126 standard. It was considered intuitive, efficient, reliable, and effective by both healthcare professionals and families, contributing to a more coordinated and informed pediatric care model.

5. Discusion

The results of this case study support the utility and effectiveness of information systems in improving pediatric primary health care. Automation of processes, the availability of relevant information, and ease of use are key factors contributing to the success of these tools. We should emphasize that we developed this system using open-source technologies, ensuring its accessibility and adaptability to various contexts. In addition, the agile methodology enabled for a quick and efficient implementation that responded to the specific needs of the clinic. The results of this case study further support the value and effectiveness of information systems in improving pediatric primary care. Process automation, access to relevant information, and user-friendliness are essential elements that contribute to the success of these tools.

Pediatricians and their partners must become aware of the technological and adaptive challenges involved in adopting these tools and collaborate with organizational leaders and developers to advocate for the best interests and safety of pediatric patients. We must consider the adoption of pediatric health information technology holistically, addressing technical, organizational, and cultural aspects to ensure optimal results.

6. Conclusions

This study used a web-based anthropometric and nutritional tracking system in Ecuador to collect a dataset and implement a decision tree model to predict body mass index (BMI) levels in children. The results indicated that variables such as age, weight, and height are significant determinants in BMI classification, while gender did not have a substantial impact on the predictive model [

18]. The decision tree allowed for a clear and comprehensible visualization of decision rules, making it easier to interpret the factors influencing children’s nutritional status. This feature is particularly valuable in a clinical context, where decisions must be transparent and based on data accessible to healthcare professionals. The decision tree model integration into the web system has proven to be an effective tool for improving decision-making in managing children’s nutritional status. By providing accurate and easily interpretable predictions, the system not only aids in the early identification of children at risk of being overweight or underweight, but also supports healthcare professionals in planning appropriate interventions.

Code availability section

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI, in order to assist suggesting references. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author Contributions

Maritza Aguirre-Munizaga: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Writing—original draft. Mitchel Vasquez-Bermudez: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization. Javier Del Cioppo: Investigation, Resources, Writing—review and editing. Luigi Chiriguayo: Software, System integration, Testing, Technical support. Leslie Chavez: Project administration, Data curation, Ethical approval management, Investigation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- INEC, I.N.d.E.y.C. Encuesta Nacional sobre Desnutrición Infantil (ENDI) 2023. p. 60.

- Huiracocha-Tutiven, L.; Orellana-Paucar, A.; Abril-Ulloa, V.; Huiracocha-Tutiven, M.; Palacios-Santana, G.; Blume, S. Child Development and Nutritional Status in Ecuador. Global Pediatric Health 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivadeneira, M.F.; Moncayo, A.L.; Cóndor, J.D.; Tello, B.; Buitrón, J.; Astudillo, F.; Caicedo-Gallardo, J.D.; Estrella-Proaño, A.; Naranjo-Estrella, A.; Torres, A.L. High prevalence of chronic malnutrition in indigenous children under 5 years of age in Chimborazo-Ecuador: multicausal analysis of its determinants. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Baik, D.; Park, Y.; Ki, M. The current status of health data on Korean children and adolescents. Epidemiology and health 2017, 39, e2017059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzt, N.H.; Salkowitz, S.M. Technology strategies for a state immunization information system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1997, 13, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edde, C.E.; Delisle, H.; Dabone, C.; Batal, M. Impact of the Nutrition-Friendly School Initiative: analysis of anthropometric and biochemical data among school-aged children in Ouagadougou. Global Health Promotion 2020, 27, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Ledesma, B.; Abril-Ulloa, V.; Pinos-Velez, V.; Carpio-Arias, V. A Descriptive Qualitative Study of the Perceptions of Regulatory Authorities, Parents, and School Canteen Owners in the South of Ecuador about the Challenges and Facilities Related to Compliance with the National Regulation for School Canteens. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.N.; Boyce, L.K.; Ortiz, E.; Santos, M.; Balseca, G. Dietary Patterns of Children from the Amazon Region of Ecuador: A Descriptive, Qualitative Investigation. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlovszky, M.; Karoczkai, K.; Jokai, B.; Ruda, B.; Kacsuk, D.; Meixner, Z. Children obesity treatment support with telemedicine. In Proceedings of the 2014 37th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics, MIPRO 2014 - Proceedings. IEEE Computer Society, 2014, pp. 275 – 278. p. 275. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Soto, G.; Aldas-Manzano, S.D. Evaluación antropométrica y hábitos alimentarios en niños escolares con desnutrición. MQRInvestigar 2023, 7, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, M.; Serrano, A.; Quaresma, R.; Pedron, C.; Romo, M. Information and communication technology adoption for business benefits: A case analysis of an integrated paperless system. International Journal of Information Management 2012, 32, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo, A. Child malnutrition in Ecuador. A literature review. Boletin de Malariologia y Salud Ambiental 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T.; Collins, C. Study protocol of a parent-focused child feeding and dietary intake intervention: The feeding healthy food to kids randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yulina, S.; Hajar, D. Kids menu care: An application for food menu scheduling with caloric balance. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. Association for Computing Machinery; 2017; p. 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Ernst, K.; Taren, D. Assessing community health: Innovation in anthropometric tool for measuring height and length. Annals of Global Health 2015, 81, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal, L.N.; Smith, M.B.; Barr, M.; Stanley, J.; Chambers, T.J.; Zhou, J.; Duane, A.; Jenkin, G.L.S.; Pearson, A.L.; Gurrin, C.; et al. Kids’Cam: An Objective Methodology to Study the World in Which Children Live. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2017, 53, e89–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobak, C.; Pek, H. Comparison of mother and child health and nutrition habits of the nursery school kids in preschool period (Aged 3-6); [Okul Öncesi dönemde (3-6 yaş) ana Çocuk sağlığı ve anaokulundaki Çocukların beslenme Özelliklerinin karşılaştırılması]. Hacettepe Egitim Dergisi 2015, 30, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Adaji, I. Serious Games for Healthy Nutrition. A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Serious Games 2022, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).