1. Introduction

ASBO is commonly seen in advanced paranasal sinus infection, which spreads along the soft tissue of base of skull and spread to the cancellous bone by invading the Harversian canals [

2]. It has a predilection of affecting sphenoid and occipital bone (particularly clivus) [

3]. There are various organisms documented in relation to ASBO; however the most prevalent organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although bacteria being the common causative agent, fungal infection has also been documented, mostly involving Aspergillus spp. In relation to its counterpart ASBO more often than not, yields negative microbiological culture, thus attaining diagnosis poses a challenge [

2,

4,

5].

Clinically, ASBO presents with non-specific symptoms, such as headache, atypical facial pain and cranial nerve paresis [

6,

7]. On clinical examination, the findings varies from no obvious findings to cranial nerve paresis and nasopharyngeal mass. Due to its difficulty in diagnosing the disease, clinicians will opt for radiological evaluation to assist in diagnosing the disease, however the imaging findings may mimic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Presence of nasopharyngeal mass on imaging findings will almost always give differential diagnosis of NPC due to its high incidence in this region [

8,

9]. Thus, histological diagnosis plays another important role in aiding the clinician to establish the diagnosis. Initial biopsy in certain patient might not be representative and unable to rule out malignancy and required a deep submucosal biopsy to rule out malignancy.

2. Case Report

A 69-year-old lady with underlying type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to casualty with a 5-month history of chronic headache. Headache was described as persistent throbbing pain which disrupts her sleep and thus affected her daily activities. Otherwise, no other significant symptoms noted. Neurological assessment was unremarkable and computed tomography (CT) scan performed shows no intracranial bleed thus patient was discharged home. Patient since then represented again to casualty 4 times with similar complaints and another CT was done. The current CT scan brain done showed an incidental fullness of left nasopharynx and was referred to ORL team.

On further history, no nasal symptoms or ear symptoms or any cranial nerve palsy noted. Flexible nasoendoscopy performed demonstrates fullness of left Fossa of Rossenmuller and proceeded with biopsy under local anaesthesia. HPE reported an acute suppurative inflammation with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Another repeated submucosal biopsy under general anesthesia performed reported no malignancy. No microbiological yield fungal bodies or acid fast bacilli. Blood investigation showed mild leucocytosis and raised inflammatory markers markedly.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) Brain & Neck (

Figure 1) was performed which showed aggressive nasopharyngeal mass with involvement of the prevertebral, left parapharyngeal and left carotid spaces; sphenoid and extensive clival bony erosion and left sphenoid sinus extension with involvement of left mastoid air cells. Correlating with the biopsy report and raised inflammatory markers, navigate us to the diagnosis of ASBO.

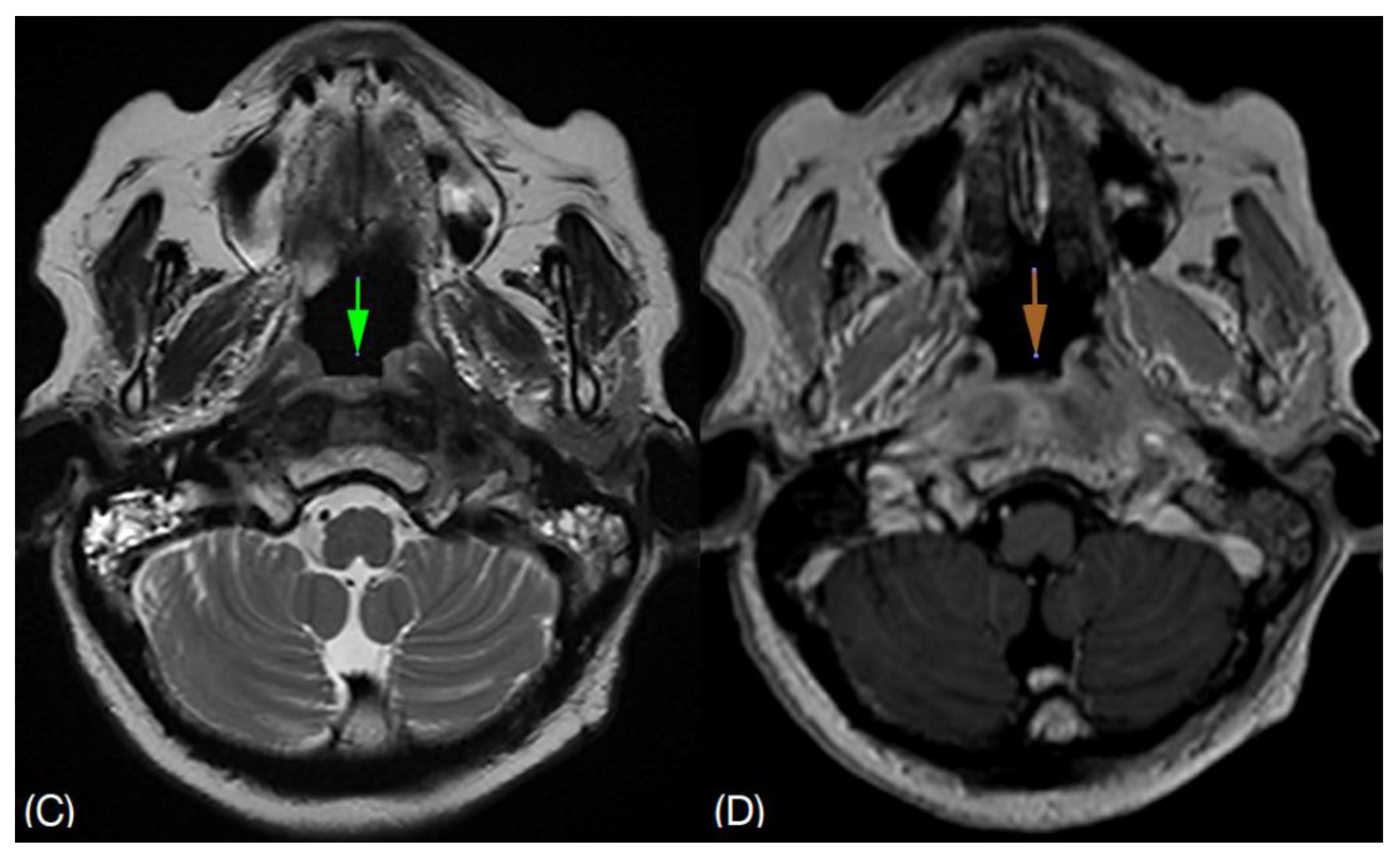

She shows clinical improvement after being treated with intravenous Tazocin (Piperacillin / Tazobactam) 4.5g QID for 3 weeks and maintaining a good glycemic control. Inflammatory markers also show a downgoing trend. Prior to discharge, she was no longer complaining of headache. She was discharged with oral Ciprofloxacin 750mg BD for 6 weeks. Subsequent follow up with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),

Figure 2 shows resolving surrounding soft tissue inflammation. Complete resolution of symptoms and normal inflammatory markers was observed after a total of 8 weeks oral antibiotic.

4. Discussion

ASBO is a rare and life threatening condition with a mortality rate of 53% [

1]. There is limited literature review and meta-analysis on ASBO thus its epidemiology is unknown [

2]. The condition commonly affects immunocompromised, diabetic and elderly patients [

1,

3,

4]. The pathogenesis that is reported to link diabetes to this disease is that; the premorbid conditions are causing damage to the vessels (micro - or macro- angiopathy) thus deterring tissue regeneration. Similar conditions that causes above reaction can be from a state causing poor oxygen delivery; which can be seen in post irradiation, bone metabolism diseases, malnutrition, anemia, smoking, obesity, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, liver or kidney failure and prolonged hospitalisation. The former conditions are all predisposed to skull base osteomyelitis [

2].

ASBO is a difficult diagnosis to make as there is no telltale sign of the disease. As per our case, ASBO typically presents with non-specific symptoms, which by itself has already caused a delay in diagnosis. In this case, ORL team was only referred after the incidental finding of a nasopharyngeal mass via CT Brain. Nasopharyngeal mass is almost always related to malignancy as the first diagnosis. Coming from one of the countries in Southeast Asia, NPC was the more common diagnosis. Radiologically, NPC commonly is seen as a distinct mucosal mass lesion [

6]. The modality of choice for ASBO would be MRI for its superior ability for soft tissue discrimination [

3]. However differentiating ASBO with NPC via imaging solely is not possible, thus histopathological and microbiological approach is important.

It has been reported that, increased level of acute phase reactant like ESR and CRP may aid in the diagnosis of ASBO as these levels are normal in malignancy [

2,

3]. Aside from that the levels also can be monitored as a determinant of duration of antibiotic [

6]. MRI is also preferred over CT scan for follow up imaging modality [

3]. However, in our case, CT scan was performed due to its readily available. In the advent of new technology in nuclear medicine radiological imaging, a complement imaging to CT scan and MRI would be positron emission tomography (PET) scan. In the literature written by PR Chapman et al, there is a positive role of Gallium-67 (PET scan) in which ASBO can be reliably excluded by the increased in uptake. This imaging modality can also be used to monitor treatment progress due to its high specificity to infection [

7].

Holistic approach is the best in managing ASBO [

3]. There is no standard protocol for the duration of antibiotic therapy for ASBO however it was recommended a 6 - 20 weeks of broad spectrum antibiotic [

4,

5,

6]. It was also suggested by the Bone Infection Unit, for 6 weeks intravenous antibiotic followed by 6 - 12 months of oral antibiotic depending on individual response [

11]. Several authors agreed on broad spectrum antibiotic covering Pseudomonas aeruginosa (antipseudomonal beta lactam, 3rd generation cephalosporin or carbapenem) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (vancomycin). With early and aggressive culture-guided, long term intravenous antifungal agent with broad spectrum antibiotic can decrease the complications arised from this disease [

2,

4,

5,

7].

Antibiotic may be discontinued once ESR & CRP level normalize, resolution of symptoms and supported by MRI changes such as resolution of abnormal soft tissue signals, enhancement or mass. It is unreliable to monitor progression by improvement in bony erosion as bony abnormalities takes weeks to months to show improvement despite clinical response [

6]. Patient should be closely monitored until disease resolution has taken place to ensure early detection of complication; namely cranial nerve palsies, intracranial abscess, thrombosis of central venous sinuses and internal jugular vein, septic embolism or mycotic aneurysm [

1,

4,

5]. Disease resolution is described as either complete resolution of symptoms and / or absence of residual lesion as evidenced by MRI skull base [

12].

Patient’s underlying illness is also monitored and optimised via multi-disciplinary team (MDT) approach to improve the disease outcome; such as glucose optimisation [

2,

3]. Surgical debridement of necrotic bone and soft tissue or draining of intracranial abscess may be needed to eradicate foci of infection and increase antimicrobial penetration [

3,

4,

7].Theoretically hyperbaric oxygen therapy may aid in tissue oxygenation thus improving phagocytosis, promoting angiogenesis and osteogenesis [

2,

3,

6], however there is insufficient research to back up its role [

2].

The global survival rate of SBO is approximately 90% at 18 months and 57% at 3 years; while a decrease by 21 - 70% is seen in the diabetic population [

8]. Recurrence is high, especially in head and neck cancer patients [

2,

10].

5. Conclusions

Diagnosis of ASBO should include thorough history, complete clinical examination not excluding radiological assessment, microbiological and histological investigations. Due to its rarity, this diagnosis should be included as one of the differentials in patients with risk factors and typical radiologic findings. Oftentimes, the diagnosis is delayed however once the diagnosis is made, aggressive treatment should be administered to reduce its morbidities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; investigation, Z.AS.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.H.; supervision, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| ASBO |

Atypical skull base osteomyelitis |

| NPC |

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| CECT |

Contrast enhanced computed tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| ESR |

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| MDT |

Mutli-disciplinary team |

References

- D. S. Deenadayal: B. Naveen Kumar, B. Vyshanavi. Osteomyelitis of the Skull Base—A Case Report. International Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery. 2018, 7, 139-142. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ijohns.

- Jure Urbancic, Domen Vozel, Saba Battelino, et al. Atypical Skull-Base Osteomyelitis: Comprehensive Review and Multidisciplinary Management Viewpoints. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 254. [CrossRef]

- Ally M, Kankam H, Qureshi A, et al. Skull Base Osteomyelitis: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Cureus 13(9): e17867. [CrossRef]

- Sohl Park, Ju Hyun Yun, Su Jin Kim, et al. A Case of Atypical Central Skull Base Osteomyelitis with Bilateral Alveolar Bone Destruction. J Rhinol 2021;28(1):57-60. [CrossRef]

- Kyoung Nam Woo, Jieun Roh, Seung Kug Baik, et al. Central skull base osteomyelitis due to nasopharyngeal Klebsiella infection. J Neurocrit Care 2020;13(2):119-122. [CrossRef]

- Pradeep Hiremath, Pradeep Rangappa, Ipe Jacob, et al. Atypical skull base osteomyelitis in the intensive care unit: A case report. Int J Diagnostic Imaging 2018;5(1):15-19. [CrossRef]

- P R Chapman, G Choudhary, A Singhal. Skull Base Osteomyelitis: A Comprehensive Imaging Review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021, 42 (3) 404-413. [CrossRef]

- Fatima AJ, Luis QB, Tania RI, et al. Diagnosis of Skuul Base Osteomyelitis. RadioGraphics 2021; 41:156–174. [CrossRef]

- Neda M, Mahshid G, Abdollah MH, et al. Epidemiology and Inequality in the Incidence and Mortality of Nasopharynx Cancer in Asia. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2016 Nov 16;7(6):360–372. [CrossRef]

- Czech MM, Hwang PH, Colevas AD, et al. Skull Base Osteomyelitis in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: Diagnosis, Management, and Outcomes in a Case Series of 23 Patients. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngology 2022,7, 47–59.

- Clark MP1, Pretorius PM, Byren I, et al. Central or Atypical Skull Base Osteomyelitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Skull B. 2009 Jul; 19(4): 247-54. [CrossRef]

- Urvashi S, Shruti V, Rayappa C. Clinical profiling and management outcome of atypical skull base osteomyelitis. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2019 Dec. 34(6), 686–689. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).