Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Meteorological Parameters

2.2. Experimental Site

2.3. Experimental Animals

2.3.1. Rabbits and Mice

2.3.2. Snakes and Scorpions

2.4. Collection of Venoms

2.5. Lethality Assay

2.6. Envenomization of Rabbits

2.7. Experimental Design

2.8. Decomposition Process

2.9. Beetles Collection and Identification

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Venoms Lethality

3.2. Meteorological Parameters

3.2.1. Atmospheric Parameters

3.2.2. On-site Recorded Weather Parameters

3.3. Decomposition Process

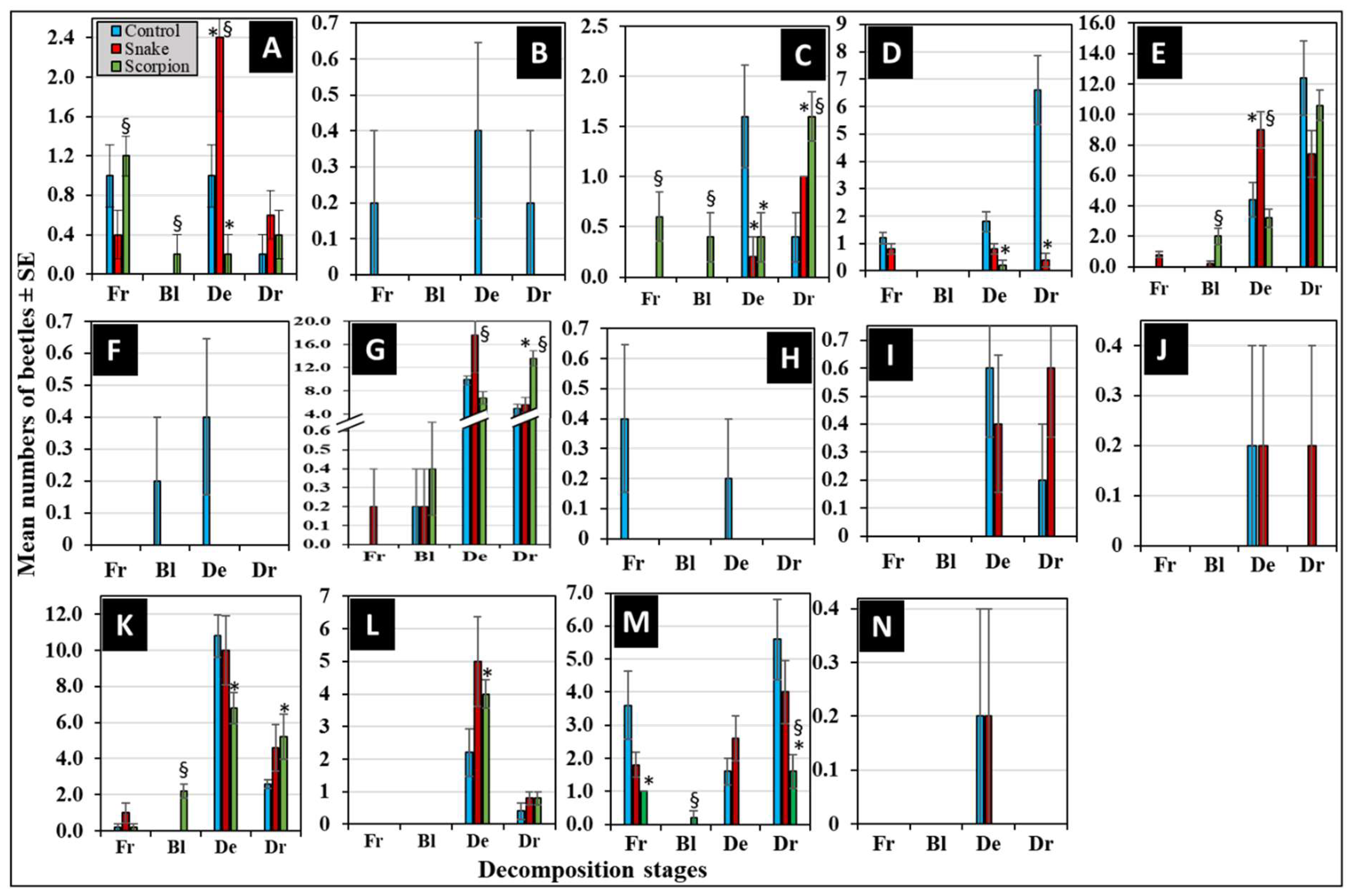

3.4. Abundance of Corpse Associated Beetles

3.5. Differential Abundance of Beetles

3.6. Differential Succession of Beetles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byrd, J.H.; Brundage, A. Forensic entomology. In: Byrd JH, Norris P, Bradley-Siemens N, editors. Veterinary forensic medicine and forensic sciences. 1st ed. Boca Raton (London, New York): CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group. 2020, 67–111.

- Amendt, J.; Richards, C.S.; Campobasso, C.P.; Zehner, R.; Hall, M.J. Forensic entomology: applications and limitations. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology 2011, 7, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charabidze, D.; Gosselin, M.; Hedouin, V. Use of necrophagous insects as evidence of cadaver relocation: myth or reality? Peerj 2017, 5, e3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Kumawat, R.; Singh, G.; Jangir, S.S.; Kushwaha, P.; Rana, M. Forensic entomology: a novel approach in crime investigation. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 19, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, R.C.; Caneparo, M.F.C.; Vairo, K.P.; de Lara, A.G.; Moura, M.O. What have we learned from the dead? A compilation of three years of cooperation between entomologists and crime scene investigators in Southern Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Entomologia 2019, 63, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.L.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liao, M.Q.; Hu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.N.; Yu, Y.M.; Wang, J.F. Estimation of post-mortem interval based on insect species present on a corpse found in a suitcase. Forensic Science International 2020, 306, 110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.H.; Castner, J.L. Forensic entomology: the utility of arthropods in legal investigations; 2019; Volume CRC press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742. ISBN: 978-0-8153-5020-0.

- Coe, J. Postmortem chemistry: practical considerations and a review of the literature. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1974, 19, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, P.; Satpathy, D.K. Use of beetles in forensic entomology. Forensic Sci Int 2001, 120, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, D.D.; Farrell, B.D. Beetles (Coleoptera). In: SB, Hedges and S, Kumar, editors. The timetree of life. Oxford University Press, USA 2009, 278-289.

- Alajmi, R.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Haddadi, R. Molecular identification of forensically important beetles in Saudi Arabia based on mitochondrial16 s rRNAgene. Entomological Research 2020, 50, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charabidze, D.; Colard, T.; Vincent, B.; Pasquerault, T.; Hedouin, V. Involvement of larder beetles (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) on human cadavers: a review of 81 forensic cases. International Journal of Legal Medicine 2014, 128, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Wan, L.H.; Yang, Y.Q.; Tang, R.; Xu, L.Z. A checklist of beetles (Insecta, Coleoptera) on pig carcasses in the suburban area of southwestern China: A preliminary study and its forensic relevance. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2016, 41, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkin, S.V.; Tsymbal, B.M.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Nuzhnaya, K.V.; Sutaeva, A.N.; Ramazanova, S.Z.; Maschenko-Grigorova, A.N.; Mishvelov, A.E. The use of model groups of necrobiont beetles (Coleoptera) for the diagnosis of time and place of death. Entomology and Applied Science Letters 2019, 6, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- White, J. Venomous animals: Clinical Toxinology. In: Luch, A, editor. Molecular, clinical and environmental Toxicology: Volume 2: Clinical Toxicology. Birkhäuser Basel, Germany. 2010, 233-291. [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P. Snakebite in Africa: current situation and urgent needs. In: Handbook of venoms and toxins of reptiles, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, London, UK. [CrossRef]

- Fathinia, B.; RASTEGAR, P.N.; Darvishnia, H.; Rajabizadeh, M. The snake fauna of Ilam Province, southwestern Iran. Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics 2010, 6, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Paray, B.A.; Al-Otaibi, H. Survey of the reptilian fauna of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. VI. The snake fauna of Turaif region. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2017, 24, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, J.A.; Seiffert, E.R. A late Eocene snake fauna from the Fayum Depression, Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 2016, 36, e1029580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C.H.; Ernst, E.M. Snakes of the United States and Canada; Smithsonian Books Washington, DC: 2003; Volume 790.

- Al-Asmari, A.K.; Al-Saif, A.A.; Abdo, N.; Al-Moutaery, K.; Al-Harbi, N. A review of the scorpion fauna of Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Journal of Natural History 2013, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, W.R. A historical approach to scorpion studies with special reference to the 20th and 21st centuries. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2014, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachel, H.S.; Al-Khazali, A.M.; Hussen, F.S.; Yağmur, E.A. Checklist and review of the scorpion fauna of Iraq (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Arachnologische Mitteilungen 2021, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P. Snake venoms and envenomations; Krieger Publishing Company. Malabar, Florida, USA: 2006.

- White, J. Bites and stings from venomous animals: a global overview. Therapeutic drug monitoring 2000, 22, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, S.; Senanayake, N. Venomous snake bites, scorpions, and spiders. Handbook of clinical neurology 2014, 120, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.A.; Holstege, C.P.; Forrester, J.D. Fatalities from venomous and nonvenomous animals in the United States (1999–2007). Wilderness & environmental medicine 2012, 23, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.A.; Weiser, T.G.; Forrester, J.D. An update on fatalities due to venomous and nonvenomous animals in the United States (2008–2015). Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 2018, 29, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.D.; Forrester, J.A.; Tennakoon, L.; Staudenmayer, K. Mortality, hospital admission, and healthcare cost due to injury from venomous and non-venomous animal encounters in the USA: 5-year analysis of the National Emergency Department Sample. Trauma surgery & acute care open 2018, 3, e000250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Goyffon, M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta tropica 2008, 107, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, R.; Fathi, B. Scorpion sting in Iran: a review. Toxicon 2012, 60, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Silva, C.G.; Neto, B.S.; Grangeiro Júnior, C.R.; Lopes, V.H.; Teixeira Júnior, A.G.; Bezerra, D.A.; Luna, J.V.; Cordeiro, J.B.; Júnior, J.G. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 2016, 27, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amr, Z.S.; Baker, M.A.A.; Warrell, D.A. Terrestrial venomous snakes and snakebites in the Arab countries of the Middle East. Toxicon 2020, 177, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneemann, M.; Cathomas, R.; Laidlaw, S.; El Nahas, A.; Theakston, R.D.G.; Warrell, D.A. Life-threatening envenoming by the Saharan horned viper (Cerastes cerastes) causing micro-angiopathic haemolysis, coagulopathy and acute renal failure: clinical cases and review. Qjm 2004, 97, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahav, G.; Weiss, A.T. Scorpion sting-induced pulmonary edema: scintigraphic evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Chest 1990, 97, 1478–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit-Prinsloo, L.; Morris, N.K.; Meyer, P.; Saayman, G. Deaths from bee stings: a report of three cases from Pretoria, South Africa. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 2016, 12, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L. A fatal case of acute renal failure from envenoming syndrome after massive bee attack: A case report and literature review. American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 2019, 40, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad Junior, V.; Amorim, P.C.H.d.; Haddad Junior, W.T.; Cardoso, J.L.C. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Revista da sociedade brasileira de medicina tropical 2015, 48, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Al-Kathiri, W.H.; Balkhi, B.; Samrkandi, O.; Al-Khalifa, M.S.; Asiri, Y. The burden of bites and stings management: Experience of an academic hospital in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi pharmaceutical journal 2020, 28, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Albeshr, M.F.; Paray, B.A.; Al-Mfarij, A.R. Envenomation and the bite rate by venomous snakes in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia over the period (2015–2018). Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhamoud, M.A.; Al Fehaid, M.S.; Alhamoud, M.A.; Alzoayed, M.H.; Alkhalifah, A.A.; Menezes, R.G. Scorpion stings in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 2021, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadoon, M.; Jarrar, B. Epidemiological study of scorpion stings in Saudi Arabia between 1993 and 1997. Journal of venomous animals and toxins including tropical diseases 2003, 9, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, B.M.; Al-Rowaily, M.A. Epidemiological aspects of scorpion stings in Al-Jouf province, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi medicine 2008, 28, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Meteorology. Meteorological services. https://ncm.gov.sa/Ar/EService/met/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on Joune, 2023). Available online: https://ncm.gov.sa/Ar/EService/met/Pages/default. (accessed on Joune, 2023).

- Al-Qurashi, A.S.; Mashaly, A.M.; Alagmi, R.; Al-Khalifa, M.S.; Mansour, L.; Al-Omar, S.Y.; Sharaf, M.R.; Aldawood, A.S.; Al-Dhafer, H.M.; Hunter, T. A preliminary investigation of rabbit carcass decomposition and attracted ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on the seaward coastal beach of Al-Jubail City, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Medical Entomology 2023, 61, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutawa, M.e.Y.; Al-Khalifa, M.S.; Al-Dhafer, H.M.; Abdel-Dayem, M.S.; Ebaid, H.; Ahmed, A.M. Forensic investigation of carcass decomposition and dipteran fly composition over the summer and winter: a comparative analysis of indoor versus outdoor at a multi-story building. Journal of Medical Entomology 2024, 61, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farhan, A.H.; Aldjain, I.M.; Thomas, J.; Miller, A.G.; Knees, S.G.; Llewellyn, O.; Akram, A. Botanic gardens in the Arabian Peninsula. Sibbaldia: the International Journal of Botanic Garden Horticulture. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Zidan, M.M.; Alajmi, R.; Ahmed, A.M. Impact of envenomation with snake venoms on rabbit carcass decomposition and differential adult dipteran succession patterns. Journal of Medical Entomology 2023, 60, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapara, M.; Thomas, B.S.; Bhat, K. Rabbit as an animal model for experimental research. Dental research journal 2012, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautartas, A.; Kenyhercz, M.W.; Vidoli, G.M.; Jantz, L.M.; Mundorff, A.; Steadman, D.W. Differential decomposition among pig, rabbit, and human remains. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2018, 63, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Salem, A.M.; Shaurub, E.-S.H.; Ahmed, A.M.; Al-Khalaf, A.A.; Zidan, M.M. Envenomation with snake venoms as a cause of death: A forensic investigation of the decomposition stages and the impact on differential succession pattern of carcass-attracted coleopteran beetles. Insects 2024, 15, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Kim, C.J.; Do, Y. Post mortem insect colonization and body weight loss in rabbit carcasses. Entomological Research 2020, 50, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeariya, M.; Hammad, K.M.; Fouda, M.A.; Al-Dali, A.G.; Kabadaia, M.M. Forensic-insect succession and decomposition patterns of dog and rabbit carcasses in different habitats. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2015, 3, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtan, A.R. Ecological notes on snake diversity in Tathleeth District, Aseer Region, Southwest of Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, B. Zoology 2017, 9, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.F. Ecological distribution of snakes’ fauna of Jazan region of Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, B. Zoology 2012, 4, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.M. Four new records of snake species in Ar’ar region, Northern border of Saudi Arabi. Jordan Journal of Natural History 2022, 9, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Sinai-Desert-Cobra. By Ltshears. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sinai-Desert-Cobra.jpg. (Visited on 24). Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sinai-Desert-Cobra. 20 December.

- Alqahtani, A.R.; Badry, A.; Abd Al Galil, F.M.; Amr, Z.S. Morphometric and meristic diversity of the species Androctonus crassicauda (Olivier, 1807)(Scorpiones: Buthidae) in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.; Al-Saief, A.; Abdo, N.; Al-Moutaery, K. New additions to the scorpion fauna of Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2009, 15, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.R.; Elgammal, B.; Ghaleb, K.I.; Badry, A. The scorpion fauna of the southwestern part of Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, B. Zoology 2019, 11, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timokhanov, V. Scorpion Androctonus crassicauda. https://freelance.ru/science_art/work-298408.html (visited on December, 2024). 2009.

- Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Orabi, G.M.; Badr, G. Toxic effects of crude venom of a desert cobra, Walterinnesia aegyptia, on liver, abdominal muscles and brain of male albino rats. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 2013, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Boghozian, A.; Nazem, H.; Fazilati, M.; Hejazi, S.H.; Sheikh Sajjadieh, M. Toxicity and protein composition of venoms of Hottentotta saulcyi, Hottentotta schach and Androctonus crassicauda, three scorpion species collected in Iran. Veterinary Medicine and Science 2021, 7, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, J.J.; Pla, D.; Els, J.; Carranza, S.; Damm, M.; Hempel, B.-F.; John, E.B.; Petras, D.; Heiss, P.; Nalbantsoy, A. Combined molecular and elemental mass spectrometry approaches for absolute quantification of proteomes: application to the venomics characterization of the two species of desert black cobras, Walterinnesia aegyptia and Walterinnesia morgani. Journal of proteome research 2021, 20, 5064–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.K.; Kunnathodi, F.; Al Saadon, K.; Idris, M.M. Elemental analysis of scorpion venoms. Journal of venom research 2016, 7, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Broad, A.; Sutherland, S.; Coulter, A.R. The lethality in mice of dangerous Australian and other snake venom. Toxicon 1979, 17, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Expert Committee on Biological Standardization, sixty-seventh report; Technical Report Series- World Health Organization. https: //iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255657/9789241210133-eng.pdf. (Visited on December, 2024): 2017; Volume 1004. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, D.J. Probit analysis 3rd edition. Cambridge University, London, UK. 1971, Volume 333. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, O.; Kar, S.; Güven, E.; Ergun, G. Comparison of proteins, lethality and immunogenic compounds of Androctonus crassicauda (Olivier, 1807) (Scorpiones: Buthidae) venom obtained by different methods. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2007, 13, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Nair, A.B.; Morsy, M.A. Dose conversion between animals and humans: A practical solution. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res 2022, 56, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtni, A.; Mashaly, A.; Haddadi, R.; Al-Khalifa, M. Seasonal impact of heroin on rabbit carcass decomposition and insect succession. Journal of Medical Entomology 2021, 58, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlee, K.; Stephens, M.; Rowan, A.N.; King, L.A. Carbon dioxide for euthanasia: concerns regarding pain and distress, with special reference to mice and rats. Laboratory animals 2005, 39, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, Y. A checklist of arthropods associated with rat carrion in a montane locality of northern Venezuela. Forensic Science International 2008, 174, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Benbow, M. When entomological evidence crawls away: Phormia regina en masse larval dispersal. Journal of Medical Entomology 2011, 48, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.D. The use of pitfall traps for sampling ants–a critique. Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria 1997, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.; Mahmoud, A.; Ebaid, H. Relative insect frequency and species richness on sun-exposed and shaded rabbit carrions. Journal of Medical Entomology 2020, 57, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, R.R.; MacMahon, J.A. Carrion decomposition and nutrient cycling in a semiarid shrub–steppe ecosystem. Ecological Monographs 2009, 79, 637–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, M.L. Early postmortem changes and stages of decomposition. In: Amendt, J., Goff, M. L., Campobasso, C. P., & Grassberger, M. (Eds). Current concepts in forensic entomology. Dordrecht: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York. 2010, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.M.A. Carrion beetles succession in three different habitats in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi journal of biological sciences 2017, 24, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, J.j.; Wilcoxon, F. A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 1949, 96, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K. Changes in the insecticide susceptibility of the American serpentine leafminer, Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae), in indoor successively reared and crop field populations over 25 years. Applied Entomology and Zoology 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.A. How to improve statistical analysis in parasitology research publications. International Journal for Parasitology 2002, 32, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, V.; Basset, Y. Rare species in communities of tropical insect herbivores: pondering the mystery of singletons. Oikos 2000, 89, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, M. Probit analysis of preference data. Applied Entomology and Zoology 1998, 33, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, K.C.; Strayer, D.L.; Likens, G.E. Fundamentals of ecosystem science; Elsevier, Academic Press. SanDiego, USA: ISBN: 978-0-12-088774-3: 2012.

- Haglund, W.D.; Sorg, M.H. Advances in forensic taphonomy: Method, theory, and archaeological perspectives (1st ed.). CRC Press. Boca Raton London New York Washington, DC. 2002.

- Vanin, S.; Zanotti, E.; Gibelli, D.; Taborelli, A.; Andreola, S.; Cattaneo, C. Decomposition and entomological colonization of charred bodies–a pilot study. Croatian medical journal 2013, 54, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, B.C.; Giardina, C.P.; Litton, C.M.; Francisco, K.S.; Pacheco, C.; Thomas, N.; Uehara, T.; Metcalfe, D.B. Impacts of insect frass and cadavers on soil surface litter decomposition along a tropical forest temperature gradient. Ecology and Evolution 2022, 12, e9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, L.; Dean, D.E.; Purcarea, C. Temperature influence on prevailing necrophagous Diptera and bacterial taxa with forensic implications for postmortem interval estimation: A review. Journal of Medical Entomology 2018, 55, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.M.A.; Al-Mekhlafi, F.A. Differential Diptera succession patterns on decomposed rabbit carcasses in three different habitats. Journal of Medical Entomology 2016, 53, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, J.; Sharma, S.; Bhardwaj, T.; Dhattarwal, S.K.; Verma, K. Seasonal study of the decomposition pattern and insects on a submerged pig cadaver. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2020, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancher, J.; Aitkenhead-Peterson, J.; Farris, T.; Mix, K.; Schwab, A.; Wescott, D.; Hamilton, M. An evaluation of soil chemistry in human cadaver decomposition islands: Potential for estimating postmortem interval (PMI). Forensic science international 2017, 279, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangerfield, C.R.; Frehner, E.H.; Buechley, E.R.; Sekercioglu, C.H.; Brazelton, W.J. Succession of bacterial communities on carrion is independent of vertebrate scavengers. Peerj 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobaugh, K.L.; Schaeffer, S.M.; DeBruyn, J.M. Functional and structural succession of soil microbial communities below decomposing human cadavers. PloS one 2015, 10, e0130201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, L.P.; See, K.L.; Ahmad, N.W.; Abdullah, K.; Hasmi, A.H. A scoping review on factors affecting cadaveric decomposition rates. Journal of Forensic Sciences and Criminal Investigation 2017, 2, 555584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, A.; Cross, P.; Moffatt, C.; Simmons, T. The effect of clothing on the rate of decomposition and Diptera colonization on Sus scrofa carcasses. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2015, 60, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.M.; Mahmoud, A.; Ebaid, H. Influence of clothing on decomposition and presence of insects on rabbit carcasses. Journal of Medical Entomology 2019, 56, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalifa, M.; Mashaly, A.; Al-Qahtni, A. Impacts of antemortem ingestion of alcoholic beverages on insect successional patterns. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 28, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtni, A.; Mashaly, A.; Haddadi, R.; Al-Khalifa, M. Seasonal impact of heroin on rabbit carcass decomposition and insect succession. Journal of Medical Entomology 2020, 58, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, F.E.; Eldeeb, S.M.; Abdellah, N.Z.; Shaltout, E.S.; Ebrahem, N.E. Influence of scorpion venom on decomposition and arthropod succession. Egypt Acad J Biol Sci B Zool 2022, 14, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edstrom, A. Venomous and poisonous animals; Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida, USA: 1992.

- Biery, T.L. Venomous Arthropod Handbook: Envenomization symptoms/treatment, identification, biology and control. Disease Surveillance Branch, Epidemiology Division, USAF School of Aerospace. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1977 O—251-048, Washington, DC. 20402, USA; 1977.

- Cichutek, K.; Epstein, J.; Griffiths, E.; Hindawi, S.; Jivapaisarnpong, T.; Klein, H.; Minor, P.; Moftah, F.; Reddy, V.; Slamet, L. WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report. Technical Report Series-World Health Organization 2017, 1004, 1–591. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, P.; Sousa, P.; Harris, D.; van der Meijden, A. Deep intraspecific divergences in the medically relevant fat-tailed scorpions (Androctonus, Scorpiones). Acta tropica 2014, 134, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aziz, A.; Kasem, S.M.; Ebrahem, N.E. Evaluation of the toxicity of scorpion venom and digoxin on human cardiovascular system and in decomposition arthropods succession using rat carrions. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, B. Zoology 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, R.H.; Ibrahim, A.E. Effects of Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) venom on postmortem changes and some biochemical parameters in rats. Forensic Science 2015, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Gawad, A.; Badawy, R.M.; Abd El-Bar, M.M.; Kenawy, M.A. Successive waves of dipteran flies attracted to warfarin-intoxicated rabbit carcasses in Cairo, Egypt. The Journal of Basic and Applied Zoology 2019, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtni, A.; Mashaly, A.; Haddadi, R.; Al-Khalifa, M. Seasonal impact of heroin on rabbit carcass decomposition and insect succession. J Med Entomol 2020, 58, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalifa, M.; Mashaly, A.; Al-Qahtni, A. Impacts of antemortem ingestion of alcoholic beverages on insect successional patterns. Saudi journal of biological sciences 2021, 28, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Fahim, A.; Salama, S.F.; Badr, G. The effects of LD50 of Walterinnesia aegyptia crude venom on blood parameters of male rats. African journal of microbiology research 2012, 6, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukkache, N.; Jaoudi, R.E.; Ghalim, N.; Chgoury, F.; Bouhaouala, B.; Mdaghri, N.E.; Sabatier, J.-M. Evaluation of the lethal potency of scorpion and snake venoms and comparison between intraperitoneal and intravenous injection routes. Toxins 2014, 6, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biologyinsights. LD50 values: Mechanisms, influences, and pharmacological applications. In: Pathology and Diseases. 2024. https://biologyinsights.com/ld50-values-mechanisms-influences-and-pharmacological-applications/?form=MG50AV53 (Visiten on December, 2024).

- WHO. World Health Organization: Progress in the characterization of venoms and standardization of antivenoms; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/37282/WHO_OFFSET_58.pdf?sequence=1 (Visited on December, 2024); 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh, S.S.; Khan, S. Purification and characterization of phosphodiesterase i from Walterinnesia aegyptia venom. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology 2011, 41, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, I.; Jemel, I.; Alonazi, M.; Ben Bacha, A. A new group II phospholipase A2 from Walterinnesia aegyptia venom with antimicrobial, antifungal, and cytotoxic potential. Processes 2020, 8, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.M.A.E.; Bourgoin-Voillard, S.; Combemale, S.; Beroud, R.; Fadl, M.; Seve, M.; De Waard, M. Fractionation and proteomic analysis of the Walterinnesia aegyptia snake venom using OFFGEL and MALDI-TOF-MS techniques. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jammaz, I. Physiological effect of LD50 of Walterinnesia aegyptia crude venom on rat metabolism over various periods of time. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2001, 4, 1429–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Alhazza, I. Effect of Walterinnesia aegyptia, Cerastes cerastes and Bitis arietans venoms on liver functions of male rats. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 2001, 33, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, F.; Zaki, K.; Naguib, M. Effect of black snake (Walterinnesia aegyptia) venom on the respiratory activity of some tissues of the rabbit. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie 1964, 48, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, T.L. Neurotoxic animal poisons and venoms. Clinical Neurotoxicology 2009, 55, 463–489. [Google Scholar]

- Safdarian, M.; Vazirianzadeh, B.; Ghorbani, A.; Pashmforoosh, N.; Baradaran, M. Intraspecific differences in Androctunus crassicauda venom and envenomation symptoms. EXCLI journal 2022, 21, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekeirsschieter, J.; Verheggen, F.; Gohy, M.; Hubrecht, F.; Bourguignon, L.; Lognay, G.; Haubruge, E. Cadaveric volatile organic compounds released by decaying pig carcasses (Sus domesticus L.) in different biotopes. Forensic Science International 2009, 189, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dakhil, A.A.; Alharbi, S.A. A preliminary investigation of the entomofauna composition of forensically important necrophagous insects in Al-Madinah Al-Munawwarah region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2020, 14, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonker, R.; RAWAT, S.; SINGH, K. Succession and life cycle of beetles on the exposed carcass. Int J Sci Innov Res 2015, 1, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.V.; Bellamy, C.L. An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles; University of California Press. Nevraumont Publishing Company, New York: 2000.

- VanLaerhoven, S.L.; Anderson, G.S. Insect succession on buried carrion in two biogeoclimatic zones of British Columbia. J Forensic Sci 1999, 44, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Venom types | LD50 (mg/kg) (lower-upper) |

LD95 (mg/kg) (lower-upper) |

Slope ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| W. aegyptia | 0.053* (0.052-0.054) |

0.066** (0.063-0.069) |

18.29 ± 3.22 |

| A. crassicauda | 1.416* (1.288-1.558) |

2.516** (2.251-2.813) |

6.59 ± 0.91 |

| Types of venoms | Days postmortem | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||||||||

| Control | ||||||||||||||||||

| W. eagiptia | ||||||||||||||||||

| A. crassicauda | ||||||||||||||||||

| Keys | Fresh stage | Bloated stage | Decay stage | Dry stage | ||||||||||||||

| Coleopteran Families (Total number) |

Beetle Species (Total number) |

Control | W. aegyptia | A. crassicauda | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fr | Bl | De | Dr | Fr | Bl | De | Dr | Fr | Bl | De | Dr | ||

| Anthicidae (38) | O. formicarius (38) | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chrysomelidae (4) | C. acaciae (4) | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cleridae (31) | N. rufipes (23) | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + |

| Necrobia sp. (8) | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | |

| Curculionidae (59) | Dinoderus sp. (57) | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | – |

| C. rhizophorae (2) | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Dermestidae (250) | D. maculatus (127) | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| D. frischi (114) | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | |

| A. posticalis (9) | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | |

| Elateridae (3) | A. grisescens (3) | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Histeridae (298) | S. chalcites (294) | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| S. caerulescens (4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | |

| Hybosoridae (3) | H. illigeri (3) | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nitidulidae (9) | C. hemipterus (8) | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| U. humeralis (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Ptinidae (3) | S. paniceum (3) | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Scarabaeidae (218) | A. adustus (181) | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| R. saoudi (10) | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | |

| M. insanabilis (27) | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Staphylinidae (66) | Philonthus sp. (62) | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + |

| Leptacinus sp. (4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Tenebrionidae (110) | M. pincticollis (22) | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – |

| T. crinite (31) | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | |

| A. diapernius (11) | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| O. punctulatus (45) | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| A. cancellate (1) | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Zopheridae (2) | Synchita sp.(2) | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).