1. Introduction

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly impacted software development, particularly through advancements in machine learning and natural language processing. For example, large language models such as

Codex [

1], Qwen, Sonnet, GPT-4 [

2] effectively support code generation, auto-completion, and error detection. Jacob Austin et al. [

3] demonstrated that fine-tuning large language models significantly improves their program synthesis capabilities, achieving high performance in synthesizing Python programs from natural language descriptions. An important study by Chen et al. [

1] evaluated Codex on the HumanEval dataset, showing that repeated sampling from the model could effectively enhance the functional correctness of generated Python programs, although it still struggles with more complex coding tasks. Specific benchmarks have been developed to support evaluation of large language models for the most relevant software development tasks: HumanEval [

1] for automatic code generation, MBPP [

3] for automatic code generation, TestEval [

4] for test case generation.

However, the application of AI, especially Large Language Models (LLMs), for software verification and in particular in dynamic analysis remains underexplored. Software verification encompasses a range of activities, including testing, where in the software is executed with diverse inputs to assess its behavior and confirm its correctness. The common methodologies employed in this process include unit testing, integration testing, system testing, and formal verification techniques, particularly for critical systems. The goal is to identify and fix defects early in the development lifecycle to ensure reliability and quality.

Large language models offer functionalities enabling software verification engineers to streamline their tasks across all stages of the verification process, including requirements analysis through natural language processing, documenting test plans, generating test scenarios, automating tests, and debugging [

5]. Although the possibility exists, few have investigated the use of LLMs for automated test case generation, one of the most time-consuming stage of software verification. In a recent study, S. Zilberman and H. C. Betty Cheng [

6] illustrated that when both programs and their corresponding test cases are generated by LLMs, the resulting test suites frequently exhibit unreliability, thereby highlighting significant limitations in their quality. Wenhan Wang et al. [

4] introduced TESTEVAL, a comprehensive benchmark containing 210 Python programs designed to assess LLMs’ capability to generate test cases, particularly measuring their effectiveness in achieving targeted line, branch, and path coverage. Importantly, all these existing studies exclusively address Python as their target language. Differentiating our approach from previous work, we explicitly focus on evaluating the effectiveness of automatically generated tests for programs written in C, placing emphasis not only on line coverage but also on the semantic correctness and practical relevance of generated tests, thus addressing a significant gap left by current methodologies.

In this context, this study investigates the efficacy of LLMs in generating program-level test cases, which are unit tests designed to verify the correctness of full C programs, addressing gaps in current methodologies, enhancing software validation processes, and improving reliability in low-level programming environments. More specifically we evaluate the top ranked LLMs in HumanEval benchmark to generate correct and diverse test cases, that offer high line coverage for the input C programs.

Our contributions are as follows: (i) we compare the leading LLMs as of January 2025 for the task of generating program-level test cases for C programs, (ii) we evaluate these models based on test case correctness and line coverage, and (iii) we analyze the impact of contextual information, such as problem statements and sample solutions, on test generation performance.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on LLM-driven software testing, highlighting the current limitations and emphasizing the research gap concerning the C programming language.

Section 3 starts with an introduction of classical methods for test case generation continues by detailing the methodology, describing tools, metrics, and datasets used in this study.

Section 4 outlines the experimental setup, discussing variations in prompts and evaluation criteria.

Section 5 presents results and analyses the effectiveness and coverage achieved by LLM-generated test cases. Finally,

Section 6 discusses implications, suggests areas for future improvement, and concludes with recommendations for advancing AI-assisted software validation.

2. Related Work

Large Language Models (LLMs) have rapidly emerged as influential tools in software testing, offering automated capabilities for test case generation, verification, and debugging. Their ability to accelerate various phases of the software testing lifecycle, from requirements analysis to post-deployment validation, has positioned them as valuable assets across a range of development environments.

Recent research has extensively examined the applications of LLMs in high-level programming languages, with a particular focus on Python, Java, and JavaScript. For example, a recent study [

5] indicates that 48% of software professionals have already integrated LLMs into their testing workflows, encompassing processes from early-stage requirements analysis to bug fixing. Nevertheless, this widespread adoption is accompanied by concerns, as issues such as hallucinated outputs, test smells [

7] (i.e., sub-optimal test choices, such as overly complex or unreliable), and false positives have been frequently observed. These challenges have led to calls for the development of structured methodologies and a cautious approach to integration.

To address these concerns, various enhancements and frameworks have been proposed. MuTAP [

8] represents a mutation-based test generation methodology that surpasses zero-shot and few-shot approaches by reducing syntax errors and improving fault detection in Python code. Similarly, LangSym [

9] enhances code coverage and scalability through symbolic execution guided by LLM-generated test inputs. In practice, these are full black-box test cases that include command-line invocations, input parameters, and any necessary external files, which together define executable testing scenarios. Tools such as CodaMosa [

10] integrate LLMs with search-based software testing (SBST) to optimize test coverage, while TestChain [

11] decouples input/output generation to improve accuracy. However, all of these solutions remain predominantly tailored to high-level languages.

Despite recent advancements, the application of LLMs to systems programming, particularly in the C programming language, remains insufficiently explored and presents significant challenges. As demonstrated in [

12], LLMs tend to produce C code of noticeably lower quality compared to other languages, characterized by reduced acceptance rates – the percentage of generated code submissions that compile successfully and pass all predefined test cases – along with issues in functional correctness, and increased complexity and security concerns. These findings indicate that LLMs encounter difficulties with the distinctive requirements of C, which include explicit memory management, pointer arithmetic, and a more stringent type system, meaning that C enforces strict rules about variable types and operations, requiring precise type declarations and conversions. Potential contributing factors may encompass biases in training data, the complexities of C semantics, and LLM architectures that are more aligned with higher-level language patterns.

Moreover, [

6] provides a critical evaluation of LLM-generated test suites for Python programs, identifying frequent test smells and a high incidence of false-positive rates, which further questions their reliability and maintainability. Although recent advancements, such as the web-based tool discussed in [

13], demonstrate potential in integrating LLM-driven automation into testing pipelines, issues such as hallucinations and logic errors continue to affect their practical utility, particularly in safety- and performance-critical domains like embedded C development.

Consequently, a notable gap persists in the existing literature: although LLMs have shown promise in automating test generation for high-level programming languages, their efficacy within the context of C programming remains limited and insufficiently explored. One contributing factor to this gap is the fundamental difference in data type systems between C and high-level languages like Python: while Python employs dynamic typing and automatic memory management, C requires strict type declarations and manual control over memory, making the generation of valid and semantically meaningful test cases significantly more complex. In addressing this gap, our study specifically targets the challenges associated with automated test generation in C. We place particular emphasis on semantic correctness, security compliance, and practical applicability, elements frequently neglected in existing LLM-driven approaches. Through this focus, we aim to reconcile the disparity between theoretical potential and practical utility in the application of LLMs to low-level, high-stakes software systems.

3. Tools and Methods

3.1. Approaches to Test Case Generation

Manual test case generation relies heavily on human expertise to design tests based on software specifications, expected behavior, and critical edge conditions. This approach ensures alignment with user priorities and functional requirements. Among the key black-box testing techniques used in this context is

Equivalence Class Partitioning (ECP), which aims to reduce testing redundancy by dividing the input and output domains into equivalence classes. Each class groups values that are expected to elicit similar behavior from the system under test, thereby allowing a representative value to sufficiently validate the entire class [

14].

Complementary to ECP is

Boundary Value Analysis (BVA), a technique that focuses on the values at the boundaries of these equivalence partitions. Given the increased likelihood of faults at input extremes, BVA plays a crucial role in detecting errors caused by off-by-one mistakes or improper range handling. It can be applied through several strategies, including robust testing, worst-case testing, or advanced methods such as the divide-and-rule approach, which isolates dependencies among variables [

15].

For systems with complex input conditions and corresponding actions,

Decision Table Testing offers a structured tabular approach that maps combinations of input conditions to actions. This technique is particularly effective in identifying inconsistencies, missing rules, and redundant logic in systems with high logical complexity. It is especially useful when testing business rules (formal logic embedded in software that reflects real-world policies, constraints, or decision-making criteria) and rule-based systems, providing a complete set of test cases derived from exhaustive enumeration of all meaningful condition combinations [

16].

Furthermore, in systems characterized by distinct operational states and transitions,

State Transition Testing proves effective. This method evaluates how a system changes state in response to inputs or events, making it especially suitable for reactive and event-driven systems. Tools such as the

STATETest framework facilitate automated test case generation from state machine models, ensuring comprehensive coverage of valid and invalid transitions, while also offering measurable coverage metrics [

17].

Together, these techniques form a robust foundation for functional test design by maximizing test coverage, improving defect detection, and reducing redundant effort through systematic abstraction and modeling.

Automated methods leverage tools and algorithms to generate test cases efficiently, covering a wide range of inputs with minimal human intervention. These techniques improve scalability, detect edge cases, and enhance reliability. Common approaches include

Symbolic Execution (e.g., KLEE in [

18]), which analyzes possible execution paths by treating program variables as symbolic values and generating input values to explore diverse scenarios.

Bounded Model Checking (e.g., CBMC in [

19]) systematically explores program states up to a certain depth, identifying logical inconsistencies, assertion violations, and potential errors.

Fuzz Testing (e.g., AFL, libFuzzer in [

20]) randomly mutates inputs and injects unexpected or malformed data into programs to uncover security vulnerabilities, crashes, and undefined behaviors.

Mutation testing evaluates the effectiveness of existing test cases by introducing small, controlled modifications (mutants) to the program code. If test cases fail to detect these modifications, it indicates gaps in test coverage. Key aspects include generating mutants by altering operators, statements, or expressions in the code, executing test cases to check whether they distinguish original code from its mutants, and identifying weaknesses in the test suite, improving test case robustness.

3.1.1. Test Case Generation in C

Generating effective test cases for C programs is essential for validating that an application performs as intended across varying scenarios. By utilizing both manual and automated approaches to test case generation, developers can enhance program reliability and ensure it meets user expectations. C programs require various types of test cases to ensure reliability and correctness. Unit test cases focus on testing individual functions or modules in isolation, using frameworks like Google Test, CUnit, and Check. For example, a factorial function should be tested with inputs such as 0, 1, and a large number to validate correctness. Boundary test cases check input limits by testing extreme values; for a function accepting integers between 1 and 100, inputs like 0, 1, 100, and 101 should be tested to verify the proper rejection of out-of-range values. Positive and negative test cases differentiate between valid inputs, which confirm expected functionality, and invalid inputs, which ensure proper error handling—such as testing a file-opening function with both a valid and nonexistent file path. Edge case testing examines unusual conditions, like testing a sorting function with an empty array, a single-element array, and an already sorted array. Integration test cases ensure multiple modules work together correctly, such as testing a database connectivity module alongside a data-processing function. Performance test cases evaluate efficiency under high loads, such as analyzing the time complexity of a sorting algorithm with increasing array sizes. Security test cases check for vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows or command injection, using tools like Valgrind or AddressSanitizer. Lastly, regression testing helps detect new bugs introduced by code modifications by running automated test suites after updates to maintain stability.

Nonetheless, existing tools present notable limitations, as they typically require access to the program’s source code and are often constrained by language-specific dependencies. They are generally incapable of generating test cases solely from natural language problem statements. Advancing software verification would therefore benefit from approaches that enable the automatic generation of test cases for C programs directly from textual specifications. Such capabilities would facilitate early-stage validation, particularly in educational and assessment contexts, while also reducing reliance on language-specific infrastructures.

3.2. Selected LLMs for Comparison

LLMs, such as GPT, Llama, Sonnet, Nova, and Qwen, have the potential to substantialy enhance test case generation for C programs by automating and optimizing various aspects of software testing. These models leverage their extensive training in code, software testing principles, and program analysis techniques to assist in generating, optimizing, and analyzing test cases. Their role can be categorized into several key areas, such as automated generation of unit test cases [

21], enhancing fuzz [

22] testing, symbolic execution assistance [

23], mutation testing automation [

24], natural language-based test case generation [

25], and code coverage analysis and optimization [

26].

For the selection of models used in comparison, we adopted an approach grounded in both the specialized literature and the up-to-date rankings (as of late December 2024) provided by the

EvalPlus leaderboard1, which evaluates models on an enhanced version of the HumanEval benchmark. EvalPlus extends the original HumanEval dataset by incorporating additional test cases to improve the reliability of

Pass@K metrics. In this context, we identified and selected the top five models ranked on the EvalPlus leaderboard, taking into account both the diversity of providers and the architectural differences among the models. This selection enables us to assess the performance of code generation algorithms in an objective and balanced manner, without favoring a particular developer or architectural family.

The purpose of this analysis is to compare the accuracy of the models on two relevant benchmarks for code generation:

HumanEval2, which tests the models’ ability to solve programming problems in a way similar to human evaluation, and

MBPP (Mostly Basic Python Programming)

3, a benchmark focused on tasks of varying difficulty in Python programming. This enables us to determine the extent to which the selected models can generalize across different problem types and whether their performance remains consistent across multiple datasets and programming languages.

Table 1 includes the five selected models along with their reported accuracy on the HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks. This table provides a clear comparative perspective on the models’ performance and serves as a reference point for further analysis of their capabilities. In the following sections, we will test these models on our dataset with the goal of generating test cases, allowing us to assess their ability to produce relevant and diverse test scenarios for evaluating code correctness and robustness.

3.3. Comparative Analysis Framework

3.3.1. Proposed Datasets

The dataset used for evaluation in this article comprises 40 introductory-level programming problems, the majority of which have been specifically designed and developed by us to ensure originality and minimize overlap with existing datasets used for training LLMs. This approach ensures an objective evaluation of the models’ ability to solve problems without external influence from pre-existing training datasets. Each problem is presented with a clearly formulated statement, a correct solution implemented in both C and Python, and a set of 8 to 12 relevant test cases designed to verify the correctness of the proposed solutions.

The problems are designed for an introductory C programming course and vary in difficulty within the scope of beginner-level concepts, covering a broad spectrum of fundamental programming topics. These include working with numerical data types, using arithmetic and bitwise operators, formulating and evaluating conditional expressions, and implementing repetitive structures. Additionally, the dataset includes exercises that involve handling one-dimensional and multi-dimensional arrays, managing character strings, and applying specific functions for their manipulation. Furthermore, it contains problems requiring the use of functions, including recursive ones, and the utilization of complex data collections such as structs, unions, and enumerations. The topic of pointers is also covered, as it is an essential concept in low-level programming languages.

For each problem, the task involves reading input data and displaying results on the standard output stream, reinforcing knowledge of fundamental input and output mechanisms in programming. The programs from the dataset include also the procedures for reading and writing files, ensuring the practical relevance of the generated tests. As a result, this dataset serves not only as a suitable environment for testing and training artificial intelligence models but also as a valuable tool for learning and deepening the understanding of essential programming principles.

3.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

Pass@K

The

Pass@K metric is widely used to evaluate the accuracy of code generation models by measuring the percentage of correct solutions within a set of K-generated samples. It aims to analyze how many of the model’s proposed solutions are valid after multiple attempts. The formula for calculating

Pass@K is:

Pass@1 indicates whether the first generated solution is correct. Pass@10 and Pass@100 are extended versions, useful in large-scale evaluations where models generate multiple code samples to increase the chances of finding a valid solution. This is essential in scenarios requiring diverse solutions [

27,

28]. In this article, the

Pass@K metric was used to evaluate the number of functionally correct test cases proposed by LLM models. Functionality is defined by executing the code in C, which is considered the correct solution to the problem, and comparing the output generated by the LLM model with the output of the code for the same input proposed by the model.

Line Coverage and LCOV for C Programs

Line coverage is a code coverage metric that measures the percentage of executed lines in a program during a test run. It helps assess the extent to which test cases exercise the code. The formula for calculating Line Coverage is:

A high Line Coverage percentage indicates that most of the code is executed by the test suite, reducing the chances of untested and potentially buggy code. LCOV is a graphical front-end for gcov, a code coverage tool used with GCC (GNU Compiler Collection). LCOV generates easy-to-read HTML reports for visualizing code coverage. We extract Line Coverage (%) from the report generated by LCOV.

4. Experimental Setup

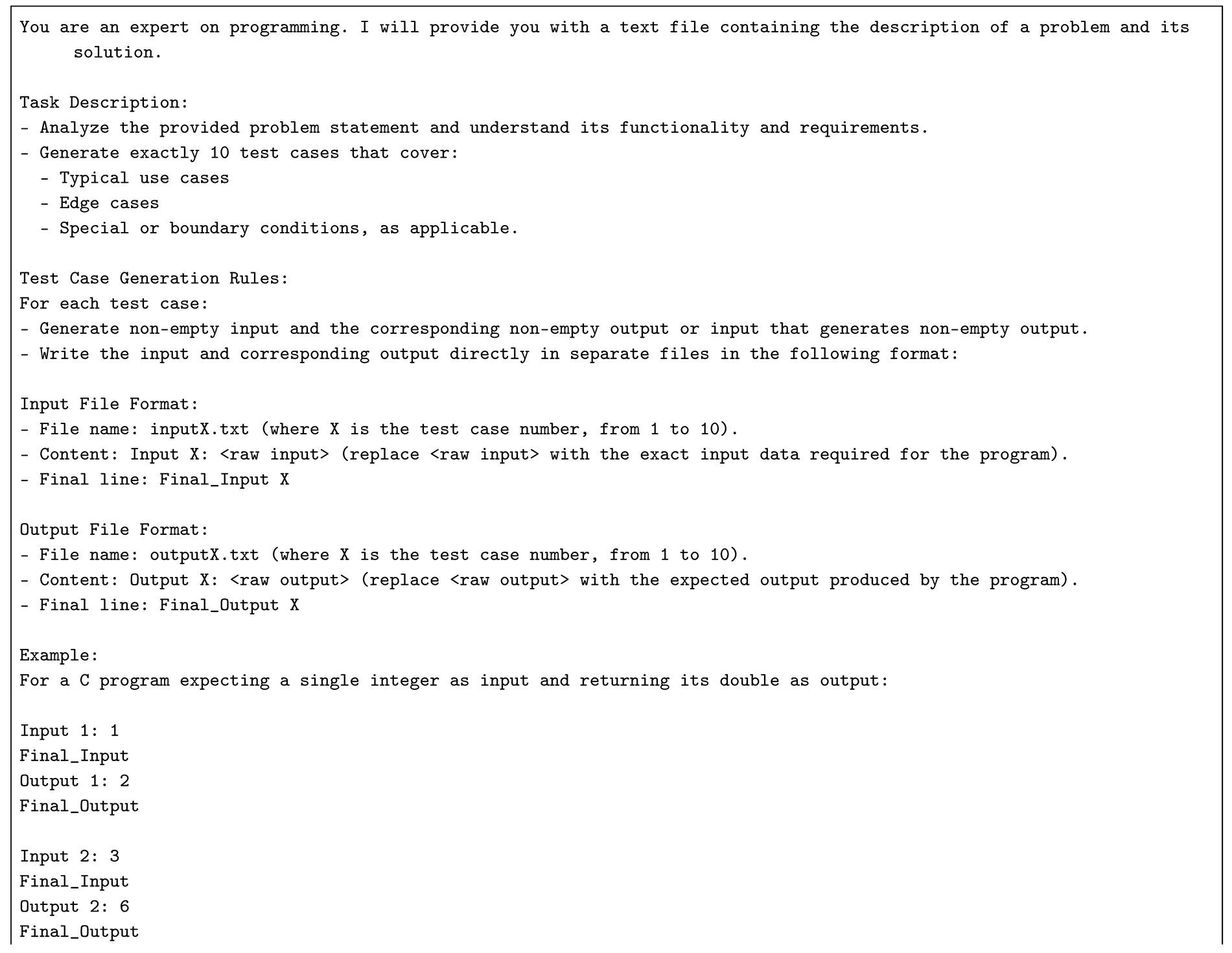

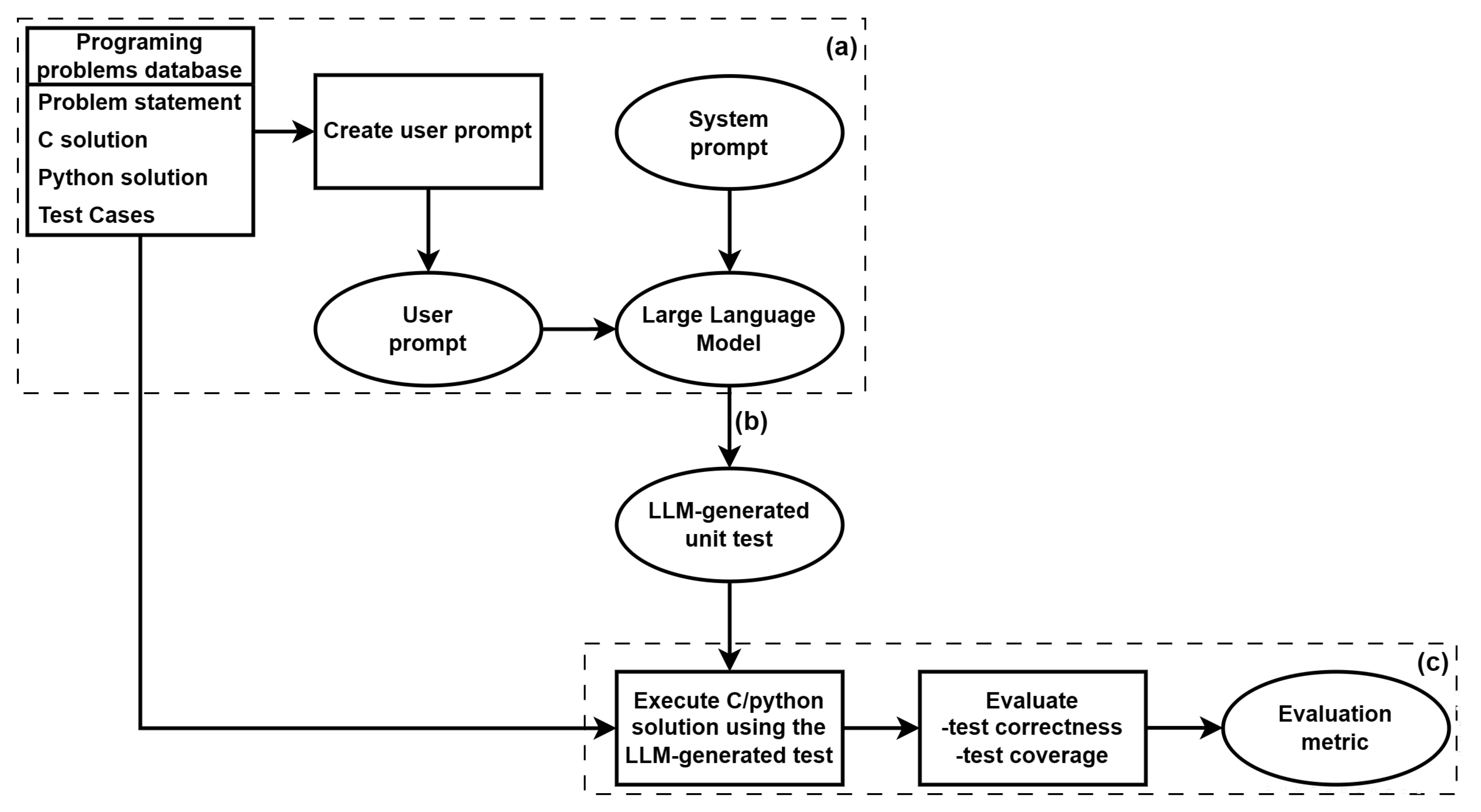

The experimental setup follows the structured workflow illustrated in

Figure 1, where a LLM is used to generate unit tests for programming problems. The process begins with a

system prompt, which ensures the LLM understands the context and task requirements. Then, a

user prompt is provided by using the information stored in the Programming Problems Database. This contains problem statements and solutions in various formats along with examples of test cases. The LLM generates test cases, which are subsequently evaluated using the ground truth code solutions from the dataset. Then, we generate the reports using the metrics defined in the previous section.

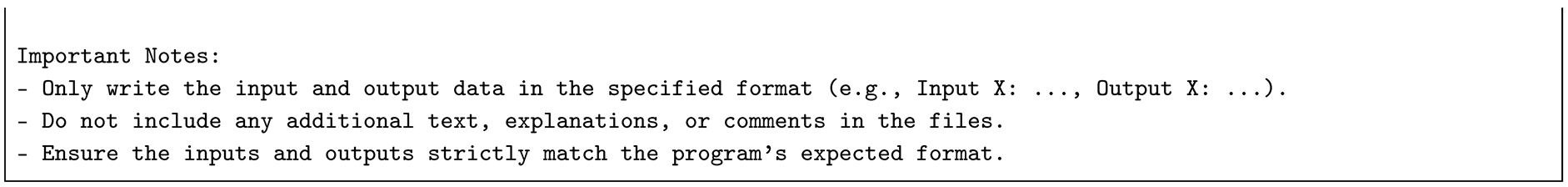

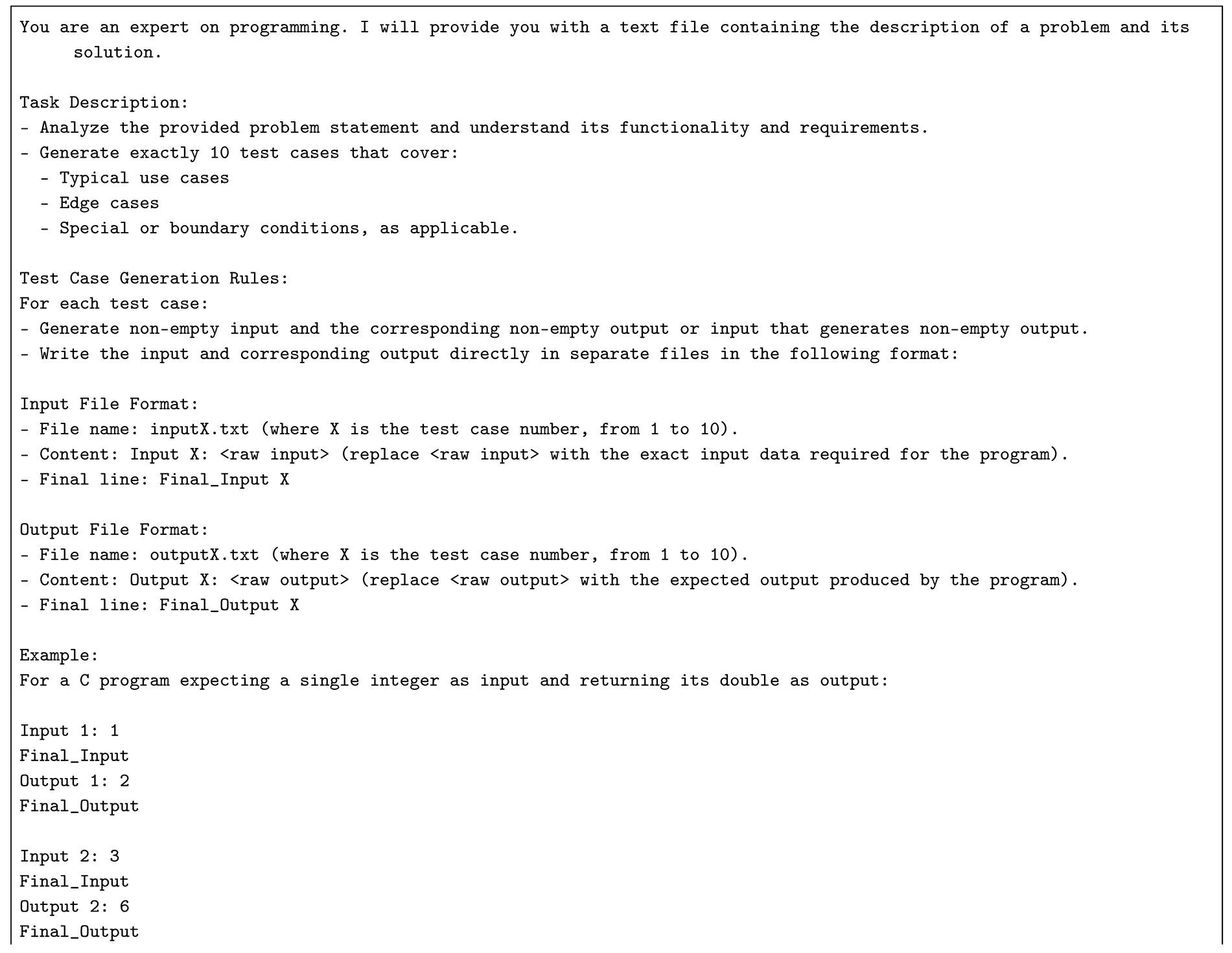

System Prompt

To maintain consistency and enforce a structured output format for easy automation, we designed the following system prompt:

The system prompt was carefully designed to enforce a standardized format for input and output files, enabling automated validation of generated test cases. Specifically, it required the generation of exactly 10 test cases per problem, systematically covering typical scenarios, edge cases, and boundary conditions. Each test case was written to separate files—inputX.txt and outputX.txt—with a consistent structure: each file begins with a labeled line (Input X: ... / Output X: ...) and ends with a marker line (Final_Input X / Final_Output X). This formatting ensures compatibility with automated scripts and facilitates framework scalability while maintaining consistency and reproducibility in testing.

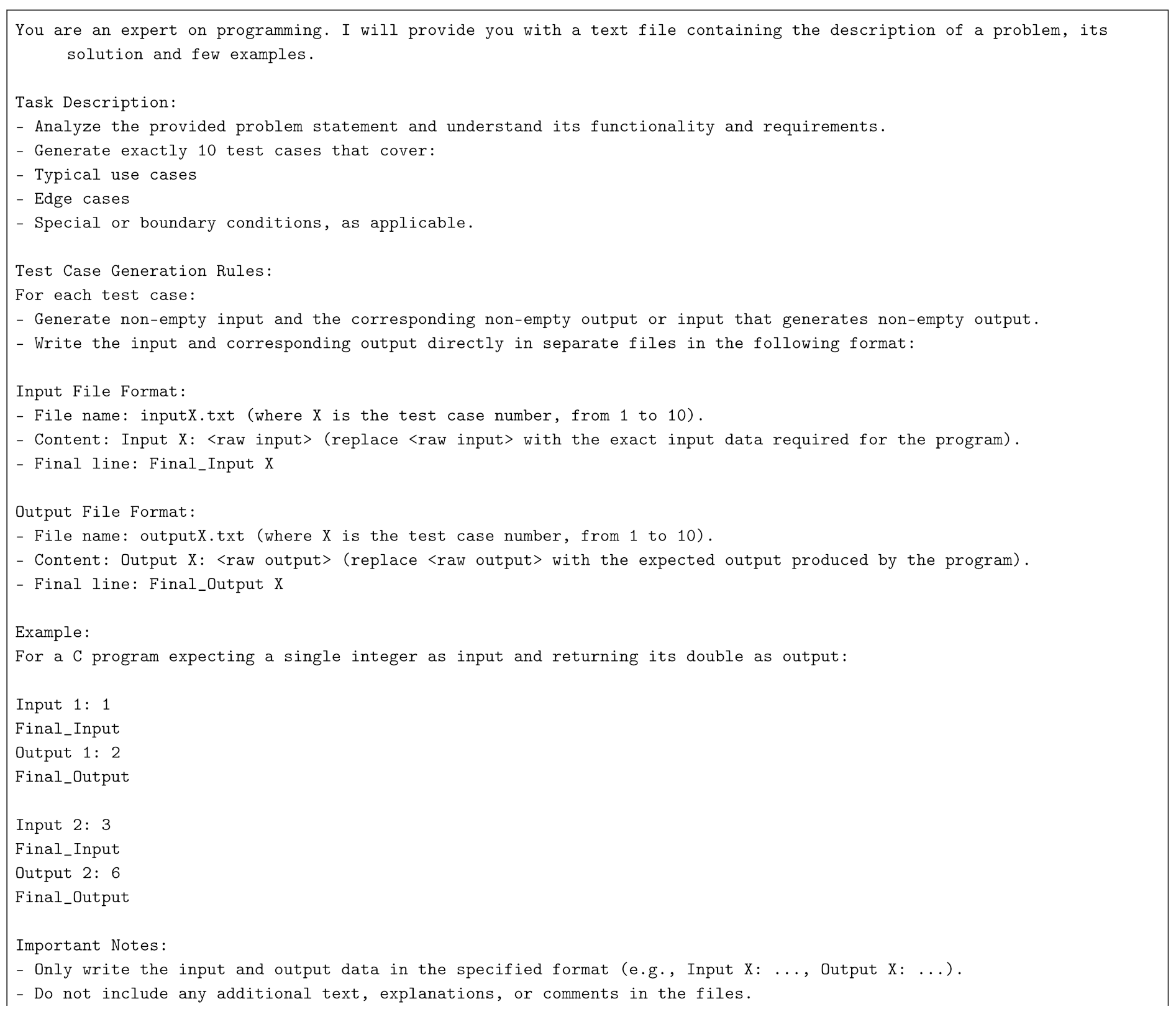

User Prompt Variations

Throughout the experiments, the user prompt varied to analyze how different types of input affected the LLM’s ability to generate meaningful test cases. The variations included are described in

Table 2. The test cases in

3tests contained real values for a specific problem statement.We include

stmt+py_sol to compare C and Python performance, with evaluation using Python.

By systematically varying the user prompt, we assessed the impact of different levels of information on the quality and relevance of generated test cases. A full example of a system and user prompt used in the

stmt+C_sol+3tests experiment is provided in

Appendix A. The five best-performing models, as identified in

Table 1, were used in these experiments. To assess the effectiveness of the generated test cases, we employed two key evaluation metrics:

Pass@1 - Measures the percentage of correct solutions that pass all generated test cases on the first attempt.

Line Coverage - Evaluates how well the generated test cases cover the solution’s lines of code.

5. Results and Discussion

Each Experiment ID corresponds to a distinct series of tests in which the input provided to the LLM was systematically varied. The specific configurations tested are detailed in the

Table 2.

For each configuration, the generated test cases were executed to determine if the program output matched exactly the expected output produced by the LLM for the given input. Performance was evaluated using the pass@k metric, where k =1 , as only a single attempt per test case was permitted.

5.1. Experimental Results

When comparing the different experiment IDs, several key observations emerged. As anticipated, models like Llama 3.3 and Claude-3.5 Sonnet demonstrated significantly improved performance when the solution was included (exp stmt+C_sol) rather than when only the problem statement was provided (exp stmt). This suggests that these models benefited from direct exposure to the C code solution rather than just the problem statement. Furthermore, when comparing the inclusion of solutions in Python versus C, GPT-4o Preview showed noticeable improvement with Python solutions, indicating that it may be better aligned with Python-based reasoning and code generation.

A more detailed comparison between experiments where only the problem statement was given, versus where both the problem statement and solution in C were provided, highlights a strong advantage in providing the solution as well. GPT-4o Preview demonstrated a substantial improvement in accuracy when both elements were included. Similarly, when evaluating whether adding three example test cases alongside the solution in C made a difference, it was evident that test case examples played a crucial role. The inclusion of three test cases led to significantly improved results for GPT-4o, Llama 3.3, and Claude-3.5 Sonnet. However, this trend was not observed for Amazon Nova and Qwen2.5, indicating that these models did not leverage example test cases as effectively.

For the 3 best-performing experiments (

stmt+C_sol,

C_sol+3tests, and

stmt+C_sol+3tests),

Table 4 presents Line Coverage (%) results, which measure the percentage of code covered by the generated test cases.

Claude-3.5 Sonnet achieved the highest code coverage overall, obtaining an Line Coverage score of 99.2% for exp

stmt+C_sol. It maintained strong results with 98.1% coverage for both exp

C_sol+3tests and

stmt+C_sol+3tests, highlighting its robustness and versatility in generating diverse and comprehensive test cases.

GPT-4o Preview also demonstrated notable performance, achieving 98.7% code coverage in experiment

stmt+C_sol and maintaining similarly high Line Coverage values across exp

C_sol+3tests and

stmt+C_sol+3tests, indicating consistent and reliable test generation capabilities.

Llama 3.3 exhibited stable and consistent coverage across the experiments, with Line Coverage values ranging from 96.1% to 98.4%, reflecting dependable performance. Similarly,

Qwen2.5 showed stable performance, achieving coverage scores consistently between 97% and 98%. Conversely,

Amazon Nova Pro had the lowest recorded Line Coverage for exp

stmt+C_sol at 95%, but it improved significantly to match other top-performing models in exp

C_sol+3tests and

stmt+C_sol+3tests, with coverage increasing to 98.1%. These detailed findings underscore

Claude-3.5 Sonnet’s superior capacity for generating thorough and diverse test cases, while also highlighting the competitive strengths and areas for improvement among other evaluated LLMs.

5.2. Strengths and Weaknesses of LLMs in C Test Case Generation

While LLMs have demonstrated impressive capabilities in generating test cases for C programs, GPT-4o Preview has a Line Coverage of 98.7% when provided the problem statement and the code in C, certain inherent limitations persist. These models generally excel at problems with straightforward logic and common patterns. However, test case generation becomes significantly more error-prone in scenarios involving floating-point precision, subtle control-flow logic, or complex mathematical expressions.

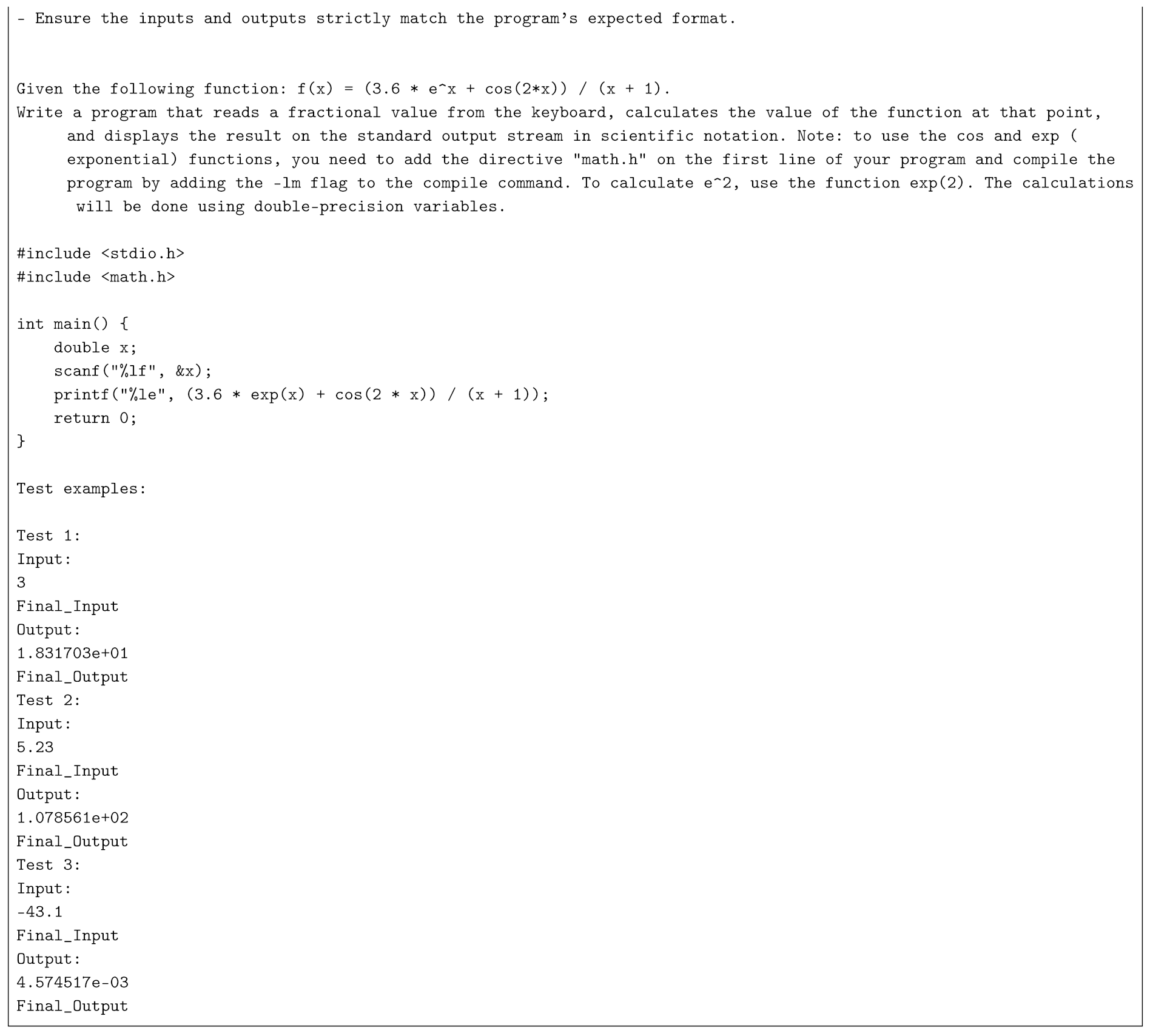

Case Study 1: Floating-Point Instability in Nonlinear Functions

Problem 5 requires computing the expression:

and displaying the result in scientific notation using double-precision floating-point arithmetic. The full description of Problem 5 is provided in

Appendix A.

Even top-tier models such as GPT-4o Preview and Claude-3.5 Sonnet failed to consistently produce all ten correct test cases. Common issues included small numerical discrepancies, such as predicting 6.347340e+00 instead of the expected 6.347558e+00. These errors stem from the fact that LLMs rely on learned approximations of floating-point behavior, rather than executing actual math functions like exp() and cos() from math.h.

An additional source of failure was the misunderstanding of angle units: some models assumed degrees instead of radians. Including clarifying comments in the prompt (e.g., “// x is in radians”) improved results, increasing test pass rates from 0 to 6 out of 10 for LLaMA 3.

Case Study 2: Logical Arithmetic Misinterpretation

Problem 9 involved reading four integers

nRows,

nCols,

row, and

col, and computing:

Models frequently failed to interpret the +1 offset correctly, sometimes simplifying it away or misapplying the logic. Even with the full problem description and correct solution, the absence of example test cases resulted in consistent underperformance across most models, suggesting difficulty with indexing logic and expression order in nested arithmetic.

These two case studies illustrate specific domains where LLMs are less effective:

Numeric computations involving floating-point behavior and math library functions.

Logical reasoning involving offsets, indexing, or nested arithmetic operations.

While advanced models still offer strong baseline performance in terms of coverage and structure, these examples expose their brittleness in scenarios that require more than learned statistical patterns. In these contexts, LLMs could benefit from hybridization with symbolic or analytical tools.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the effectiveness of Large Language Models (LLMs) in generating program-level test cases for C programs, specifically focusing on unit tests. Unlike previous research, which has primarily concentrated on Python, our approach was focused on C. We highlighted not only the line coverage but also the semantic accuracy and practical applicability of the generated tests. By evaluating the top-ranked LLMs from the HumanEval benchmark, we addressed significant gaps in existing methodologies and contribute to the advancement of software validation in low-level programming environments.

As expected, the results indicate that LLMs perform significantly better when provided with both the problem statement and its solution in C, rather than just the problem statement alone. Including example test cases in the input further enhances performance, though the degree of improvement varies across different models. While models like GPT-4o Preview, Llama 3.3, and Claude-3.5 Sonnet demonstrated substantial gains when given additional test cases, Amazon Nova and Qwen2.5 did not show notable benefits from this added context.

Claude-3.5 Sonnet and GPT-4o Preview emerged as the strongest performers, achieving both high pass@1 scores and Line Coverage, demonstrating their ability to generate precise and effective test cases. On the other hand, Qwen2.5 and Amazon Nova Pro consistently underperformed, suggesting that they are less sensitive to additional context in the form of solutions or example test cases.

Overall, the findings highlight the importance of providing structured input to LLMs for generating effective test cases. To avoid potential data contamination and ensure a fair evaluation, we used original problems and C code not publicly available, thereby reducing the likelihood that these examples were part of the models’ training data. In these controlled conditions, we specifically analyzed whether starting from a correct solution enables an LLM to generate meaningful test cases that focus solely on verification. By comparing outputs under different input configurations (problem statement alone vs. statement plus code), our study contributes to a clearer understanding of how contextual information influences test generation quality. This approach offers practical insights into leveraging LLMs more effectively in real-world software validation workflows, especially for low-level programming environments where correctness is critical.

In addition, we analyzed in depth two problem types that expose specific limitations of LLMs in test case generation for C programs. The first involves floating-point computations using math library functions, where models often failed to produce precise outputs due to reliance on approximations rather than actual numerical evaluation. The second concerns logical reasoning tasks involving offsets, indexing, or nested arithmetic expressions, where misinterpretation of subtle operations—such as off-by-one logic—was common. The findings highlight that, although advanced models generally achieve high coverage, they exhibit a high sensitivity to contexts that demand precise numerical reasoning or structural logic. The inclusion of additional contextual information in the prompt enhanced performance, suggesting that future improvements may be realized by integrating large language models (LLMs) with symbolic or analytical tools.

Given these findings, future research directions are proposed to further enhance the effectiveness of LLMs in test case generation. Future research could explore a broader set of C programs with varying complexities, investigate fine-tuning LLMs on C-specific or testing datasets, and integrate static or dynamic analysis tools to better assess test quality. Additionally, combining LLM-generated tests with traditional methods may help address the current limitations in reliability and coverage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B. and H.C.; methodology, G.N. and A.G.; software, A.G.; validation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, G.N., H.C. and C.B.; supervision, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. System Prompt + User Prompt Example For Problem 5

References

- M. Chen, J. Tworek, H. Jun, Q. Yuan, H. P. de O. Pinto, J. Kaplan, H. Edwards, Y. Burda, N. Joseph, G. Brockman, et al., "Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code," arXiv preprint, vol. 2107.03374, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03374.

- R. A. Poldrack, T. Lu, and G. Beguš, "AI-assisted coding: Experiments with GPT-4," arXiv preprint, vol. 2304.13187, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.13187.

- J. Austin, A. Odena, M. Nye, M. Bosma, H. Michalewski, D. Dohan, E. Jiang, C. Cai, M. Terry, Q. Le, and C. Sutton, “Program Synthesis with Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07732, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07732.

- W. Wang, C. Yang, Z. Wang, Y. Huang, Z. Chu, D. Song, L. Zhang, A. R. Chen, and L. Ma, “TESTEVAL: Benchmarking Large Language Models for Test Case Generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04531, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04531.

- R. Santos, I. Santos, C. Magalhaes, and R. de Souza Santos, "Are We Testing or Being Tested? Exploring the Practical Applications of Large Language Models in Software Testing," arXiv preprint, vol. 2312.04860, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.04860.

- S. Zilberman and H. C. Betty Cheng, "“No Free Lunch” when using Large Language Models to Verify Self-Generated Programs," in *Proc. 2024 IEEE Int. Conf. Softw. Test. Verif. Valid. Workshops (ICSTW)*, 2024, pp. 29-36. [CrossRef]

- W. Aljedaani, A. Peruma, A. Aljohani, M. Alotaibi, M. W. Mkaouer, A. Ouni, C. D. Newman, A. Ghallab, and S. Ludi, “Test Smell Detection Tools: A Systematic Mapping Study,” in *Proc. 25th Int. Conf. Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (EASE)*, Trondheim, Norway, 2021, pp. 170–180. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Dakhel, A. Nikanjam, V. Majdinasab, F. Khomh, and M. C. Desmarais, "Effective Test Generation Using Pre-trained Large Language Models and Mutation Testing," arXiv preprint, vol. 2308.16557, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.16557.

- J. Xu, J. Xu, T. Chen, and X. Ma, "Symbolic Execution with Test Cases Generated by Large Language Models," in *Proc. 2024 IEEE 24th Int. Conf. Softw. Qual. Rel. Security (QRS)*, 2024, pp. 228-237. [CrossRef]

- C. Lemieux, J. P. Inala, S. K. Lahiri, and S. Sen, "CodaMosa: Escaping Coverage Plateaus in Test Generation with Pre-trained Large Language Models," in *Proc. 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th Int. Conf. Softw. Eng. (ICSE)*, 2023, pp. 919-931. [CrossRef]

- K. Li and Y. Yuan, "Large Language Models as Test Case Generators: Performance Evaluation and Enhancement," arXiv preprint, vol. 2404.13340, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.13340.

- Z. Liu, Y. Tang, X. Luo, Y. Zhou and L. F. Zhang, "No Need to Lift a Finger Anymore? Assessing the Quality of Code Generation by ChatGPT," in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 1548-1584, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Sami, Z. Rasheed, M. Waseem, Z. Zhang, H. Tomas, and P. Abrahamsson, "A Tool for Test Case Scenarios Generation Using Large Language Models," arXiv preprint, vol. 2406.07021, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.07021.

- A. Bhat and S. M. K. Quadri, “Equivalence class partitioning and boundary value analysis – A review,” in Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), IEEE, 2015, pp. 1557–1562.

- X. Guo, H. Okamura, and T. Dohi, “Optimal test case generation for boundary value analysis,” Software Quality Journal, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 543–566, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. YK, “Decision Table Based Testing,” International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication, vol. 3, pp. 1298–1301, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Intana and A. Sawedsuthiphan, “STATETest: An Automatic Test Case Generation Framework for State Transition Testing,” in Proceedings of the 2023 20th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- C. Cadar and M. Nowack, "KLEE symbolic execution engine in 2019," International Journal on Software Tools for Technology Transfer, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 867–870, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Kroening, P. Schrammel, and M. Tautschnig, CBMC: The C Bounded Model Checker, arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02384, 2023.

- Z. Yu, Z. Liu, X. Cong, X. Li, and L. Yin, "Fuzzing: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives," Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 78, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Alshahwan, J. Chheda, A. Finegenova, B. Gokkaya, M. Harman, I. Harper, A. Marginean, S. Sengupta, and E. Wang, “Automated Unit Test Improvement using Large Language Models at Meta,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.09171, 2024. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.09171.

- T. Wang, R. Wang, Y. Chen, L. Yu, Z. Pan, M. Zhang, H. Ma, and J. Zheng, “Enhancing Black-box Compiler Option Fuzzing with LLM through Command Feedback,” in Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), pp. 319–330, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, K. Liu, A. R. Chen, G. Li, Z. Jin, G. Huang, and L. Ma, “Python Symbolic Execution with LLM-powered Code Generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.09271, 2024. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.09271.

- F. Tip, J. Bell, and M. Schaefer, “LLMorpheus: Mutation Testing using Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.09952, 2025. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.09952.

- R. Pan, M. Kim, R. Krishna, R. Pavuluri, and S. Sinha, “ASTER: Natural and Multi-language Unit Test Generation with LLMs,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.03093, 2025. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.03093.

- N. Do and C. Nguyen, “Generate High-Coverage Unit Test Data Using the LLM Tool,” International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, vol. 13, pp. 13–18, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhong, Z. Wang and J. Shang, "Debug like a Human: A Large Language Model Debugger via Verifying Runtime Execution Step-by-step," arXiv preprint, arXiv:2402.16906, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.16906.

- T. X. Olausson, J. P. Inala, C. Wang, J. Gao, and A. Solar-Lezama, "Is Self-Repair a Silver Bullet for Code Generation?," arXiv preprint, arXiv:2306.09896, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.09896.

- C. E. A. Coello, M. N. Alimam, and R. Kouatly, “Effectiveness of ChatGPT in Coding: A Comparative Analysis of Popular Large Language Models,” Digital, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 114–125, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-6470/4/1/5. [CrossRef]

- A. Bouali and B. Dion, “Formal Verification for Model-Based Development,” in Proceedings of SAE 2005 World Congress & Exhibition, Apr. 2005. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- A. Ulrich and A. Votintseva, “Experience report: Formal verification and testing in the development of embedded software,” in Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), 2015, pp. 293–302. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Rabbi, A. I. Champa, M. F. Zibran, and M. R. Islam, “AI Writes, We Analyze: The ChatGPT Python Code Saga,” in Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR ’24), Lisbon, Portugal, 2024, pp. 177–181. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- B. Idrisov and T. Schlippe, “Program Code Generation with Generative AIs,” Algorithms, vol. 17, no. 2, Article 62, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4893/17/2/62. [CrossRef]

- F. Subhan, X. Wu, L. Bo, X. Sun, and M. Rahman, "A deep learning-based approach for software vulnerability detection using code metrics," *IET Software*, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 516-526, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).