Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

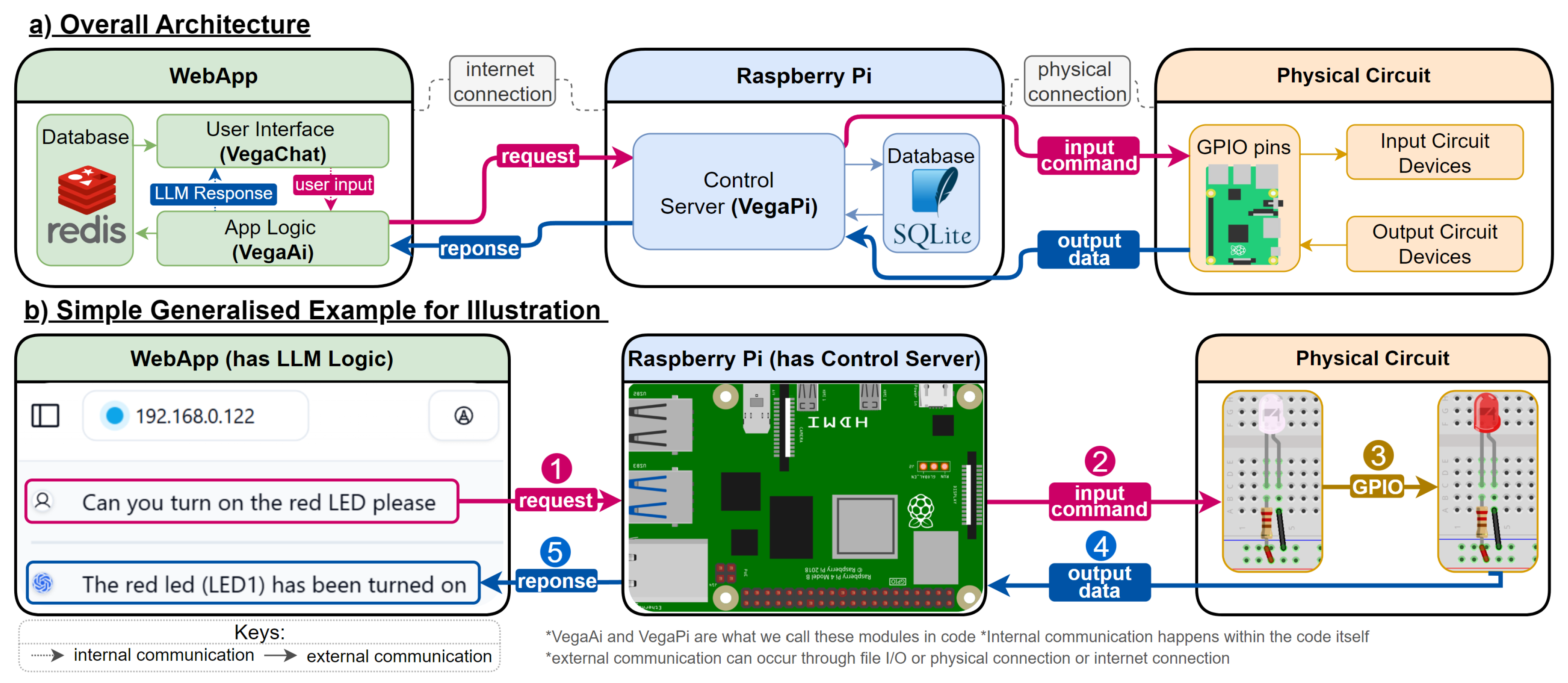

- We developed a chat web app that executes queries on the RPi which contains a control server that manages the execution on a circuit and communication with the web app.

- We develop a multi-agent LLM framework that translates natural language commands into executable instructions for IoT devices, capable of handling complex, conditional logic without additional coding on the RPi.

- We showcase the system’s real-world applicability through physical circuit implementations and provide insights into its limitations and potential scalability.

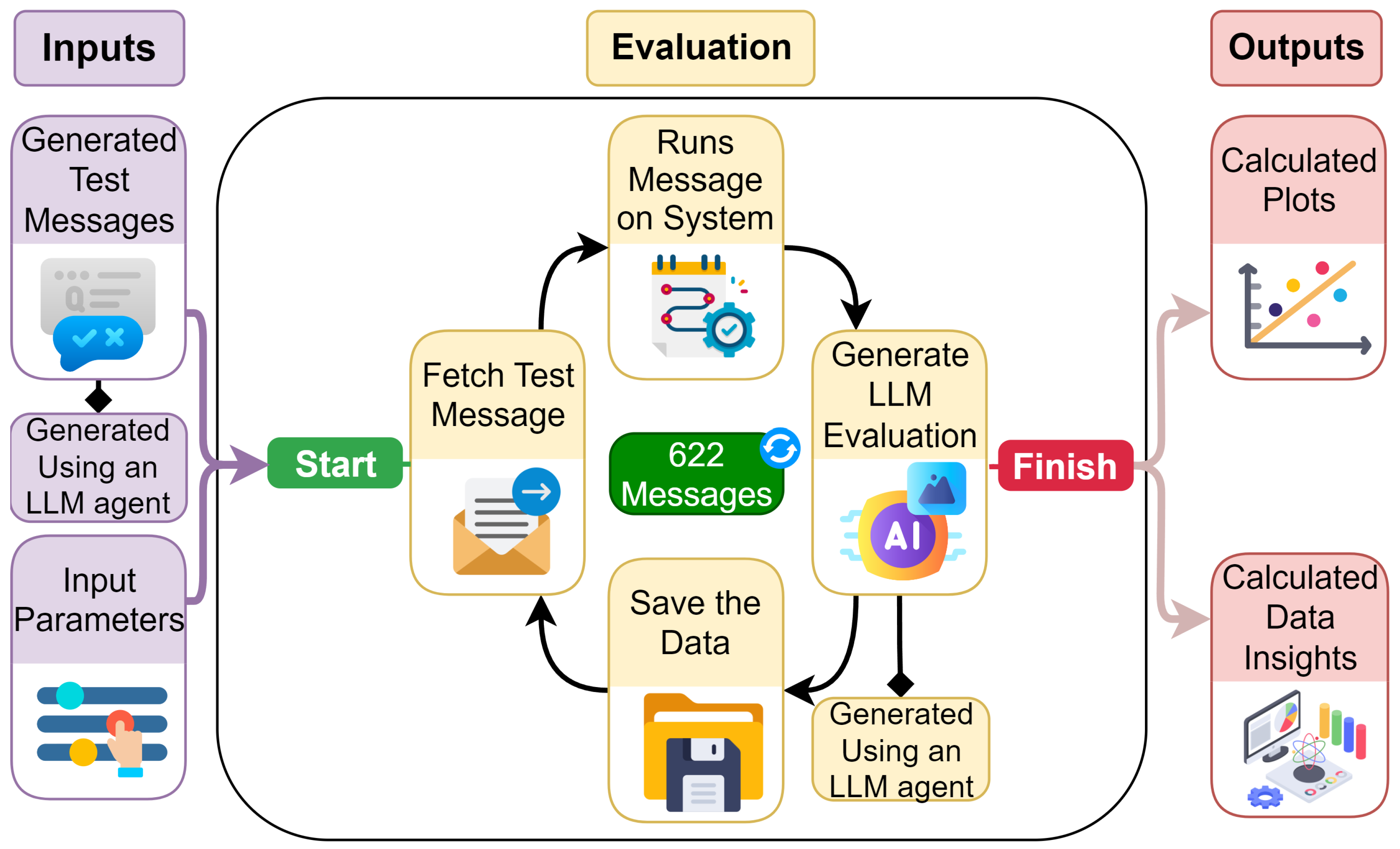

- We implement and evaluate the system demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of LLM-driven IoT control across various task complexities and user scenarios, including an evaluation mode with automated test generation and performance assessment.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Industrial Applications of LLM’s

2.2. Natural Language Processing for IoT

2.3. Language Oriented Architectures

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Architecture

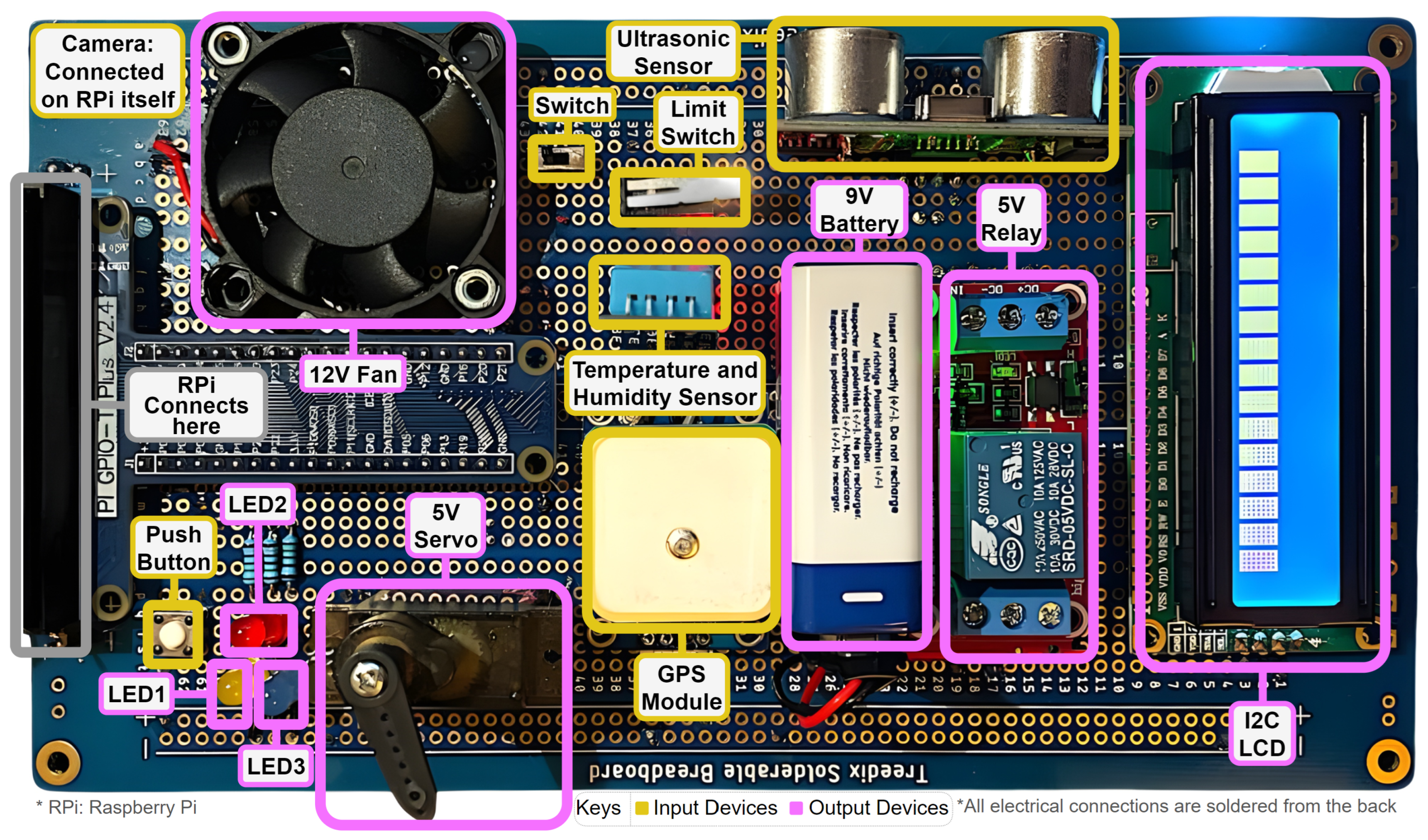

3.2. Physical Circuit Design

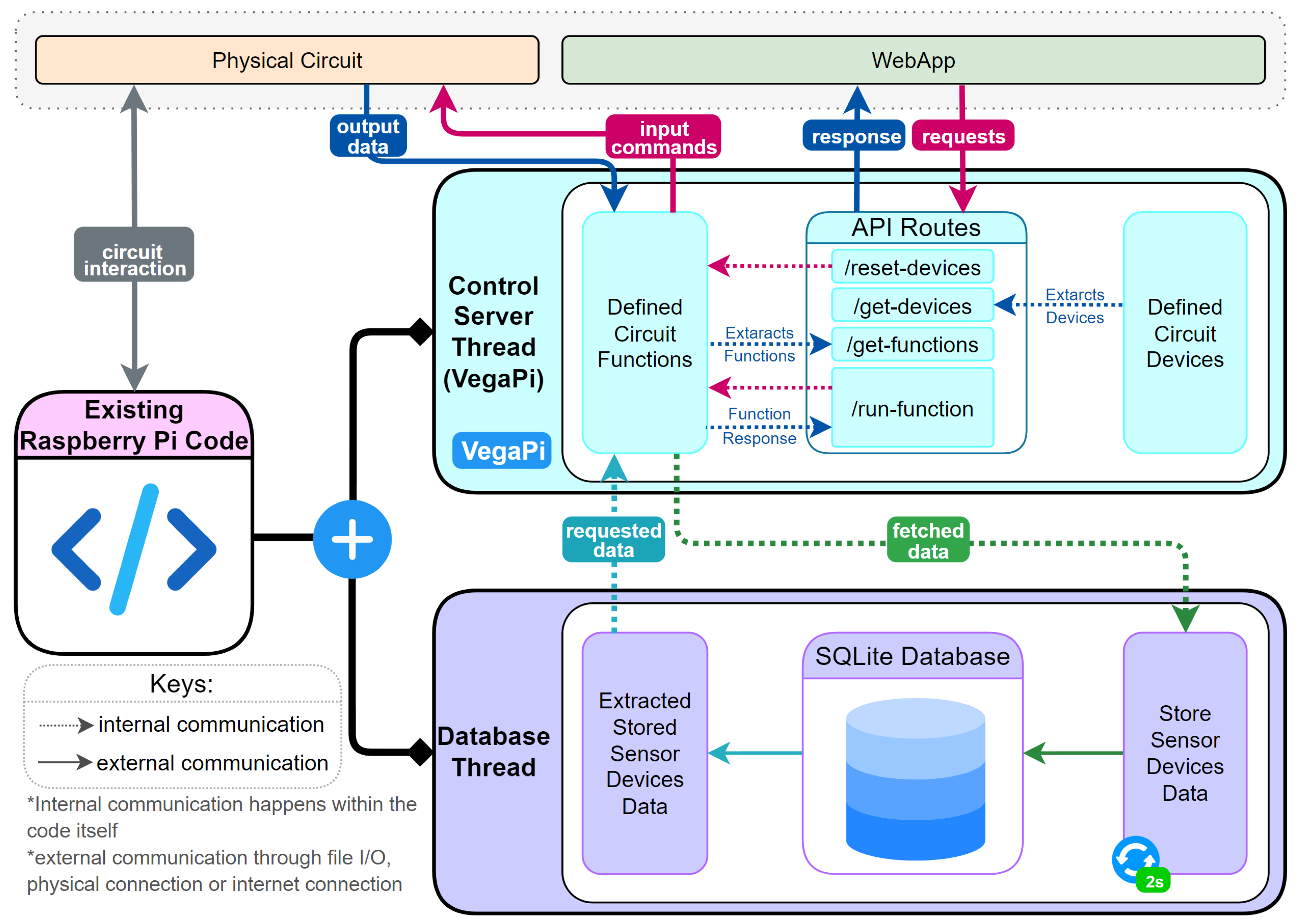

3.3. Raspberry Pi Design

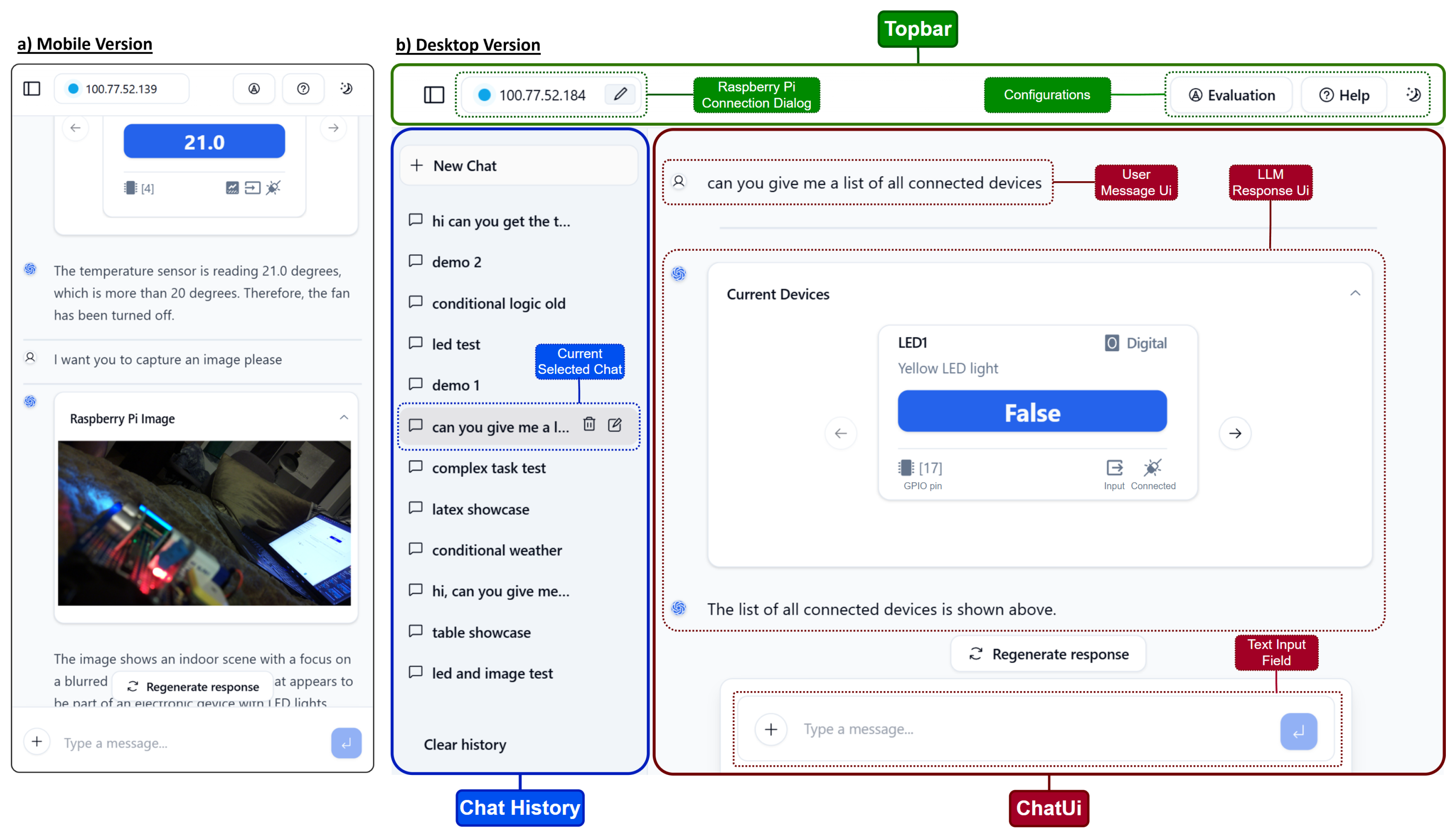

3.4. Web App User Interface

3.5. Web App Logic

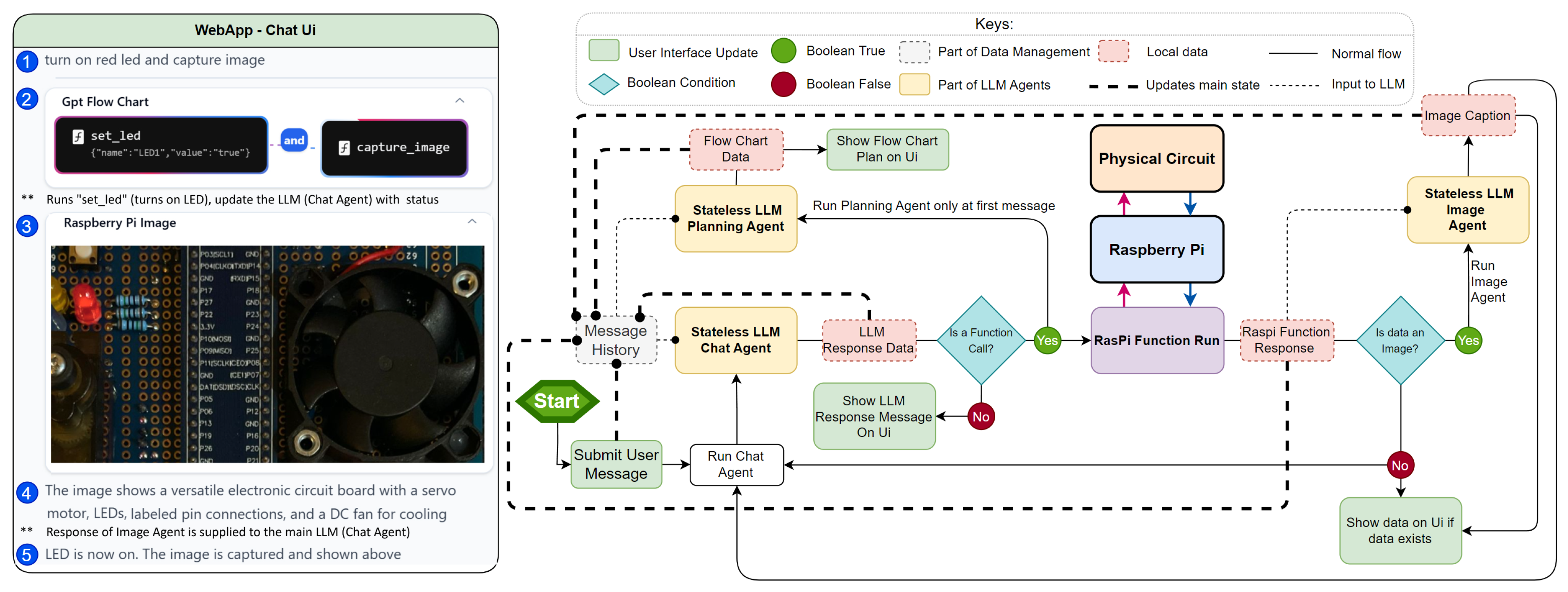

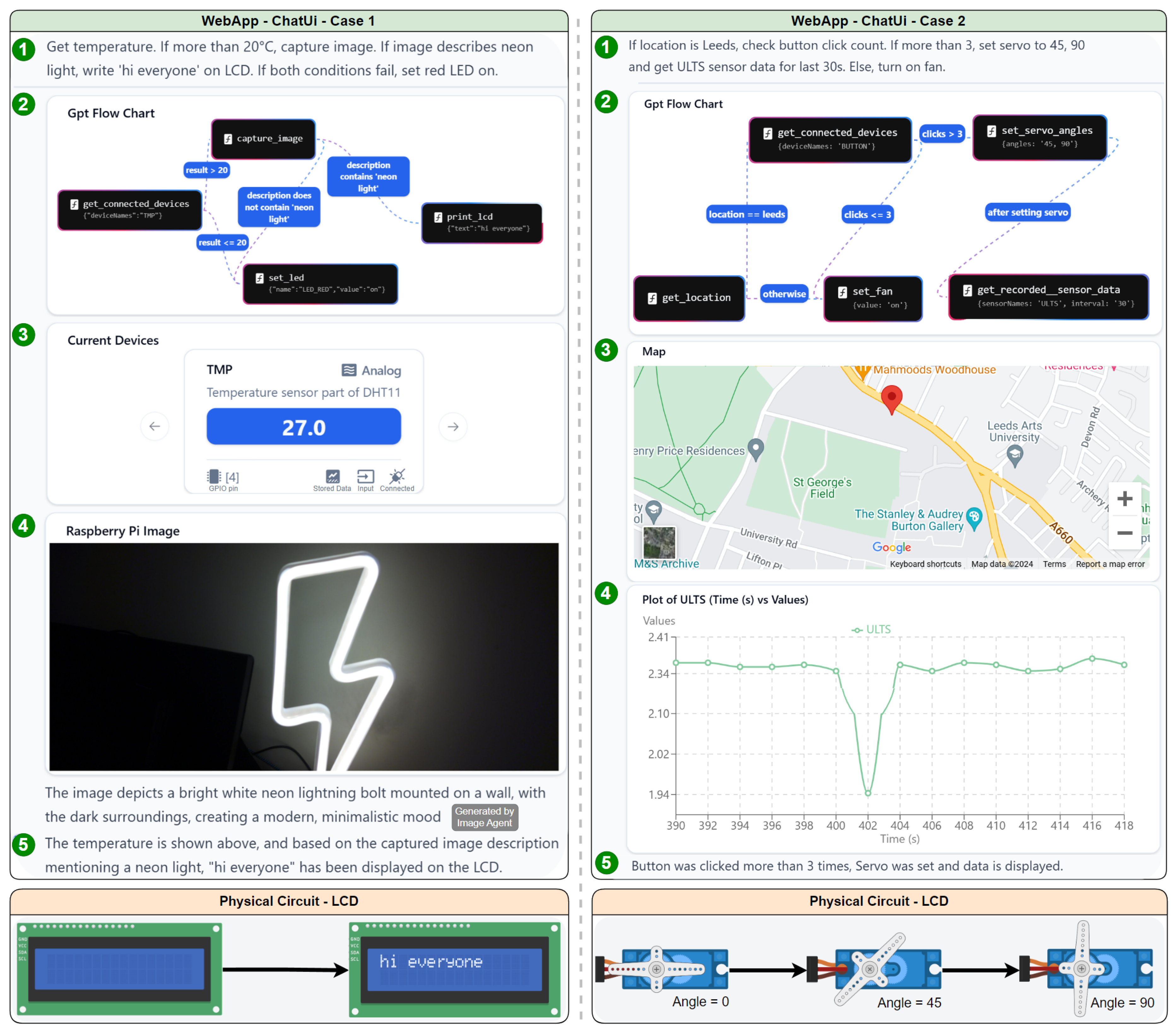

- The Stateless LLM Planning Agent generates a plan which is visualized as a flowchart in the user interface.

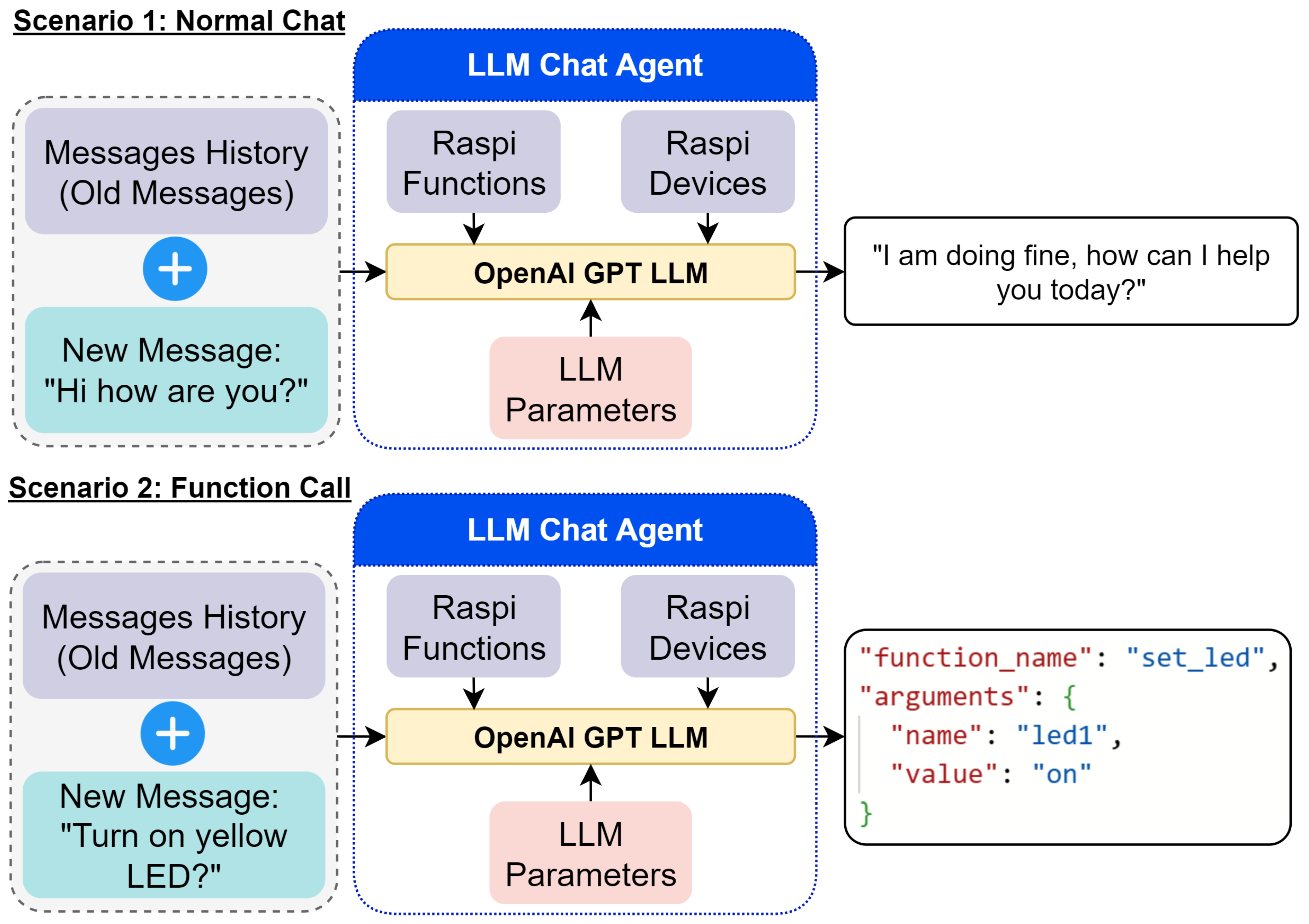

- The Stateless LLM Chat Agent processes the message and determines if a function call to the RPi is necessary.

- If required, the function is sent and executed on the RPi, which returns a response.

- For image data, the Stateless LLM Image Agent analyse and generates a description used by the LLM Chat Agent to execute subsequent functions and logic.

- Results are displayed on the web application’s UI, providing feedback to the user.

4. Experiment and Validation

4.1. Representative Real life case study

4.2. Automated Evaluation

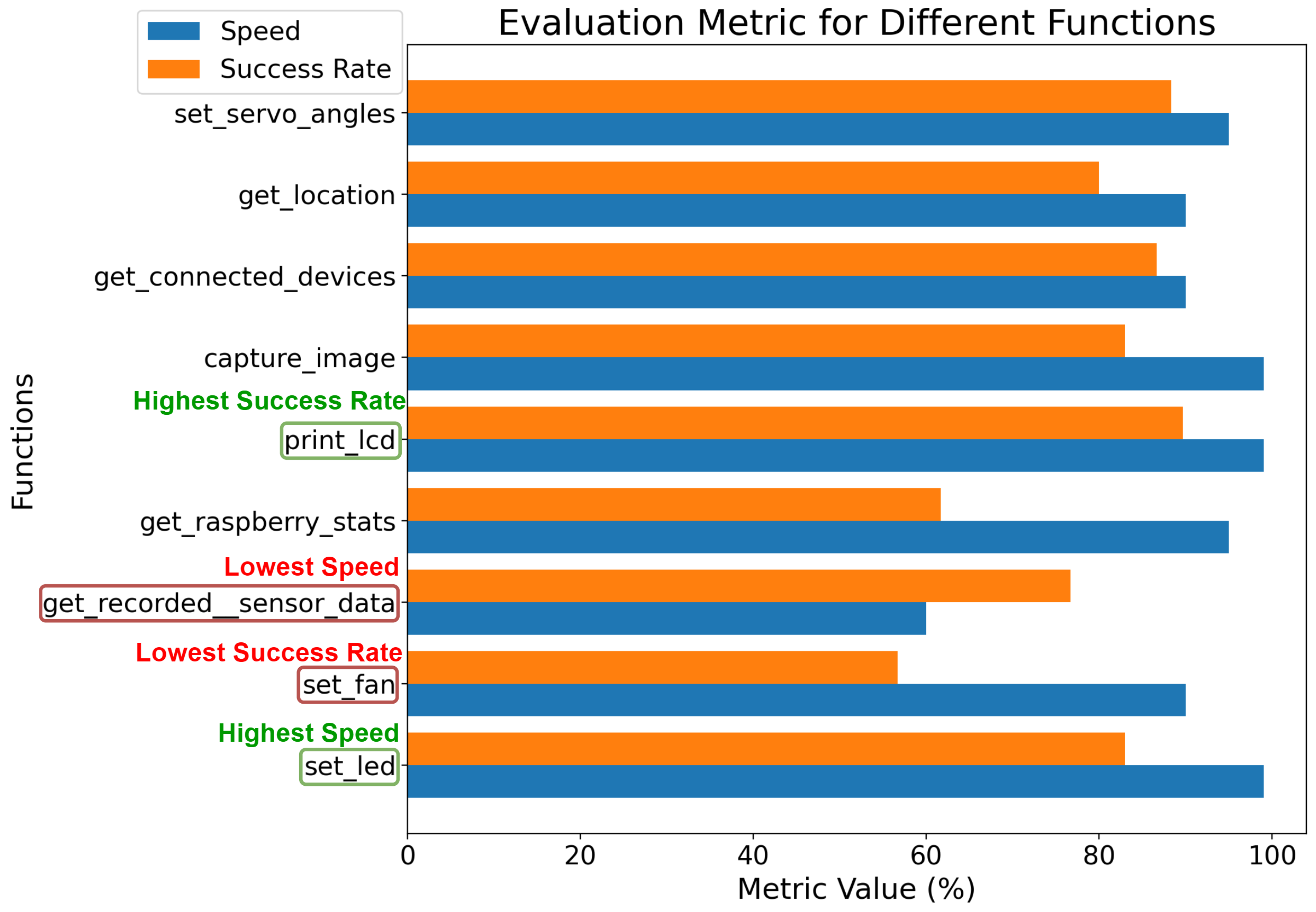

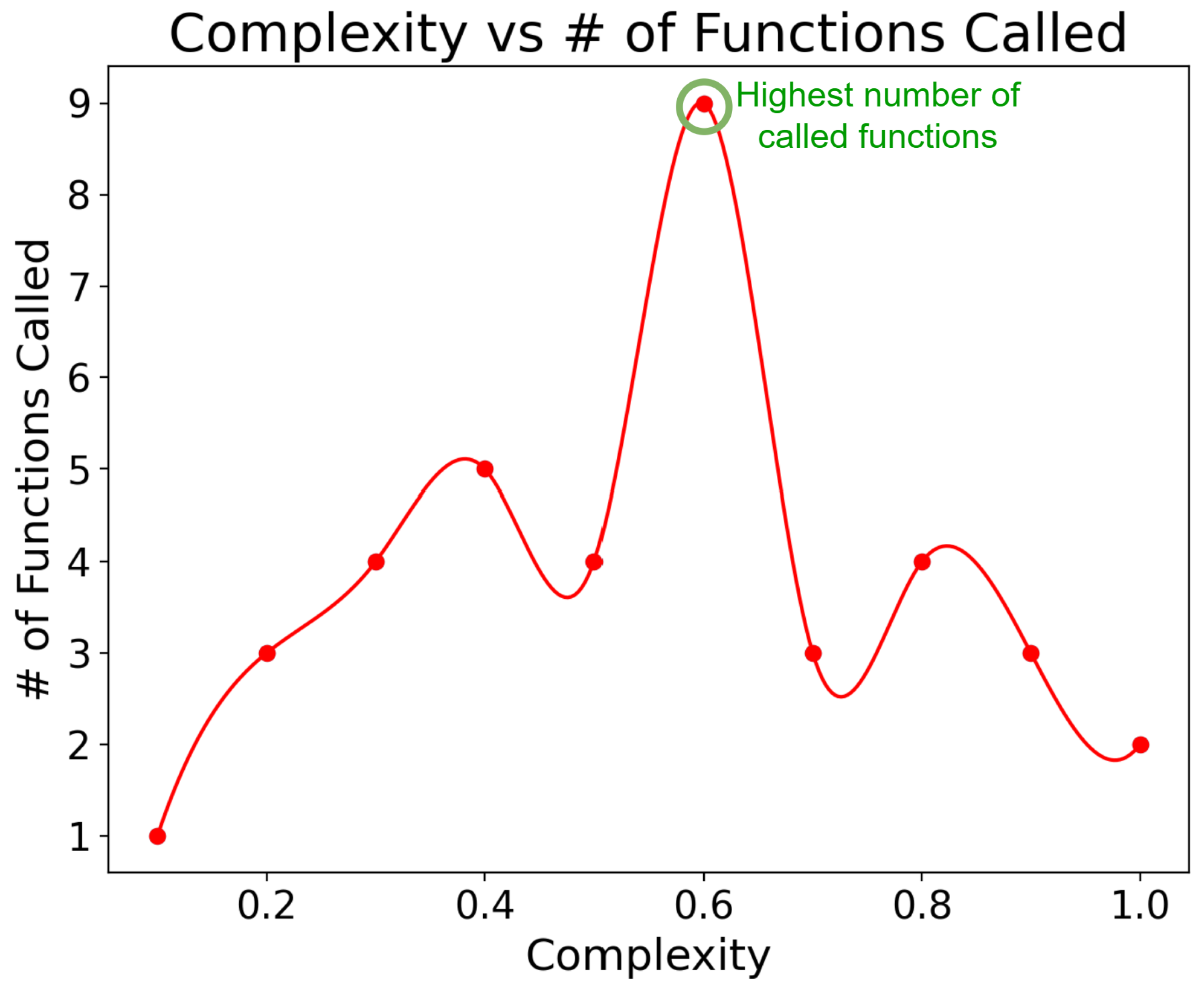

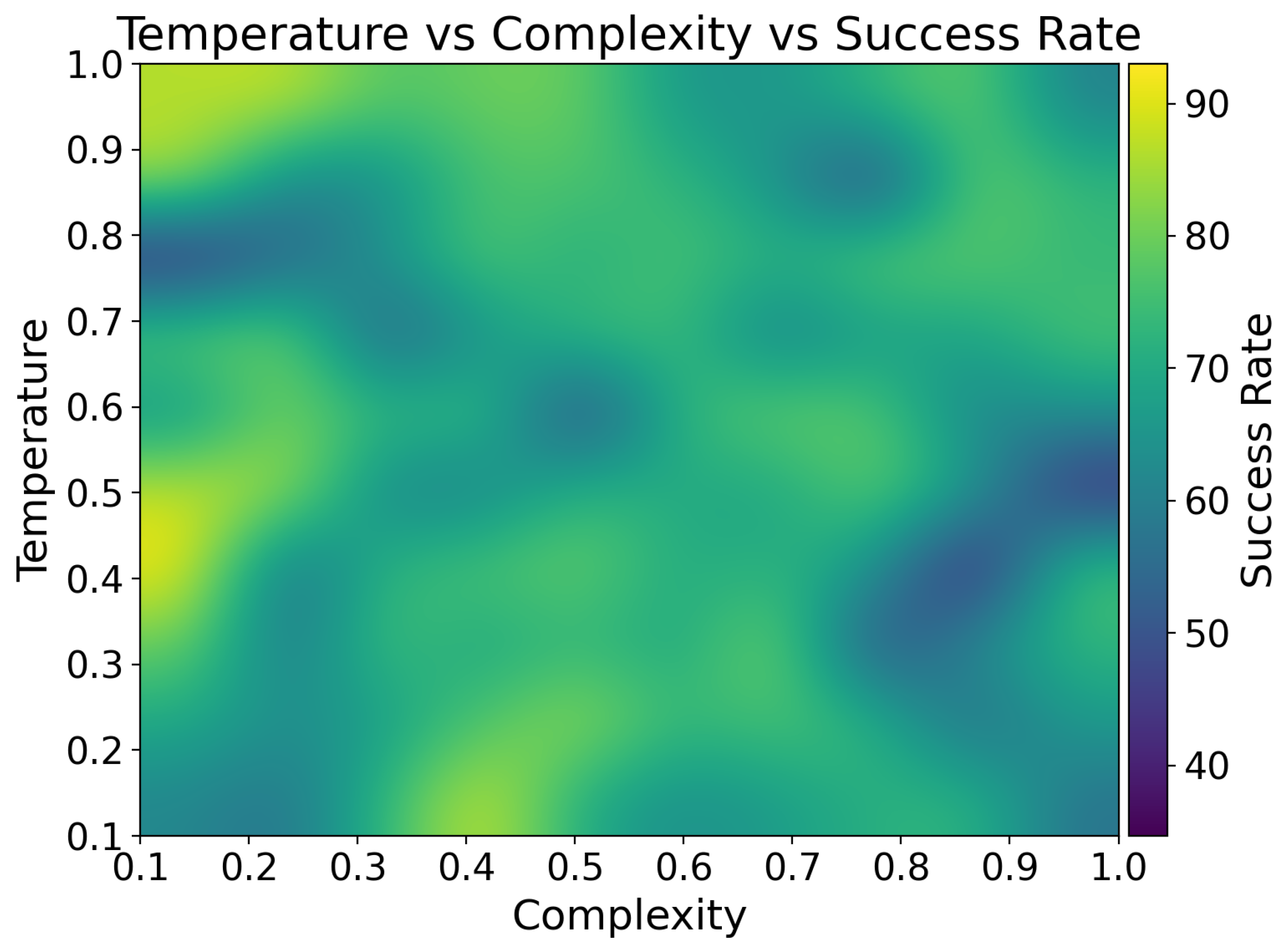

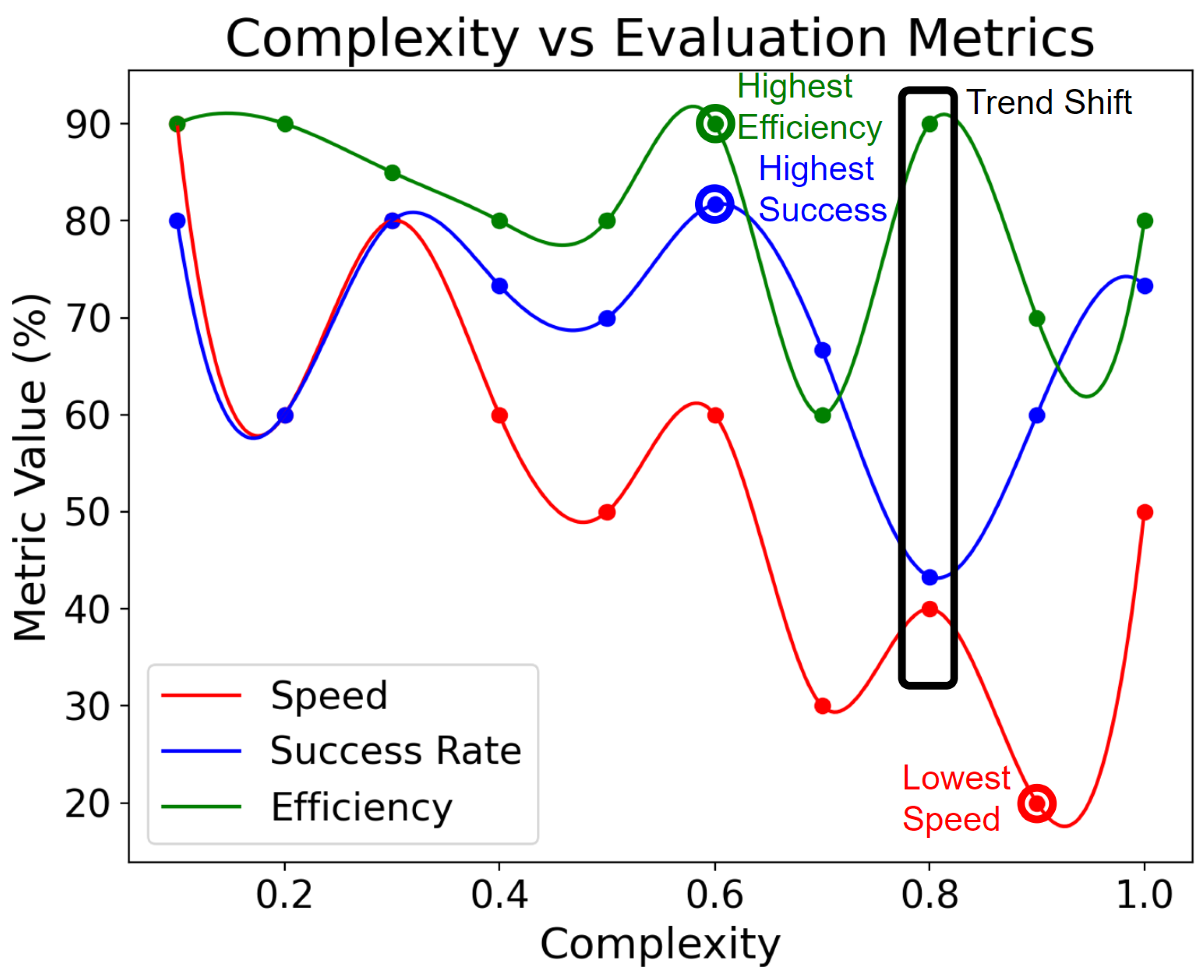

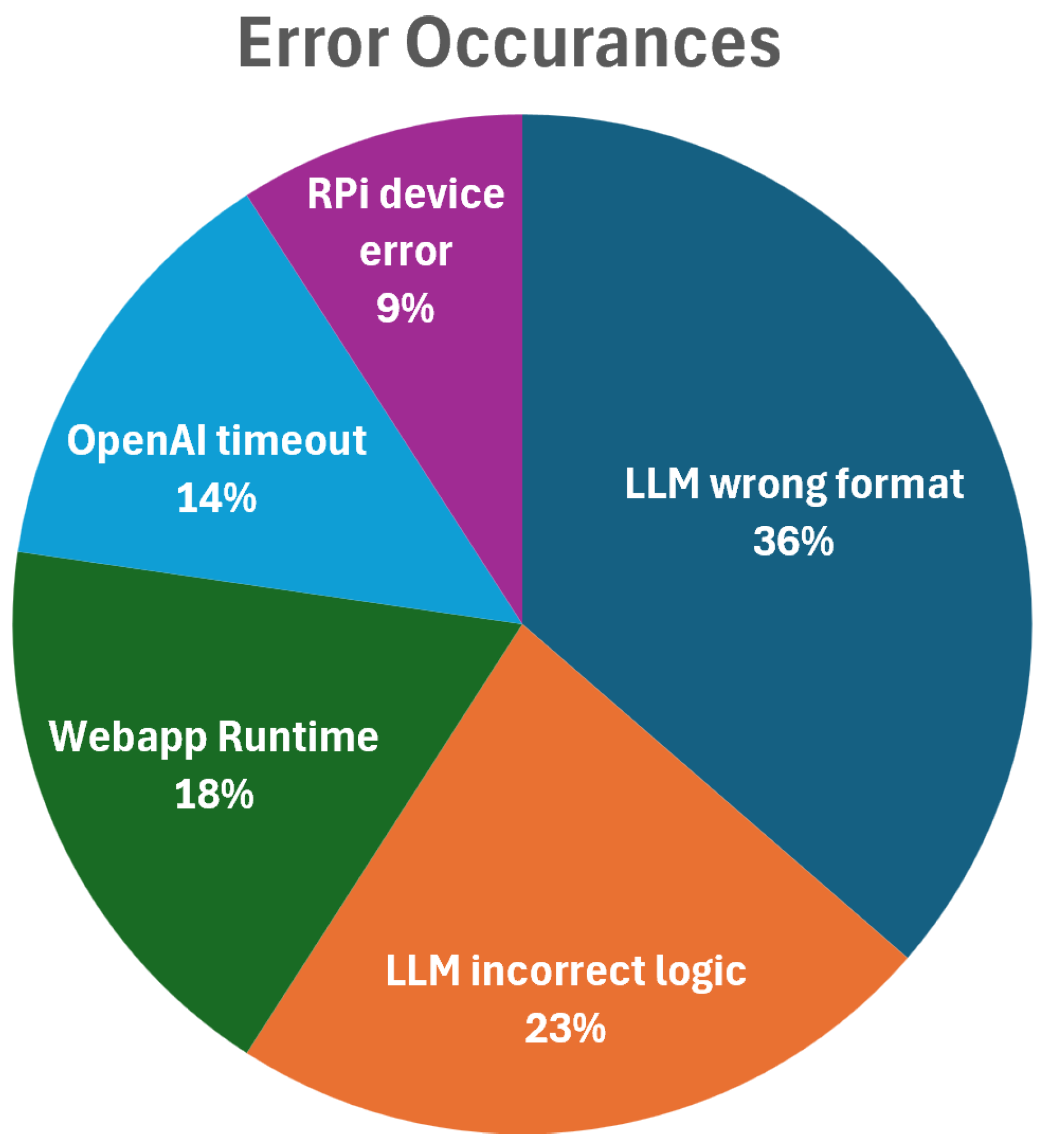

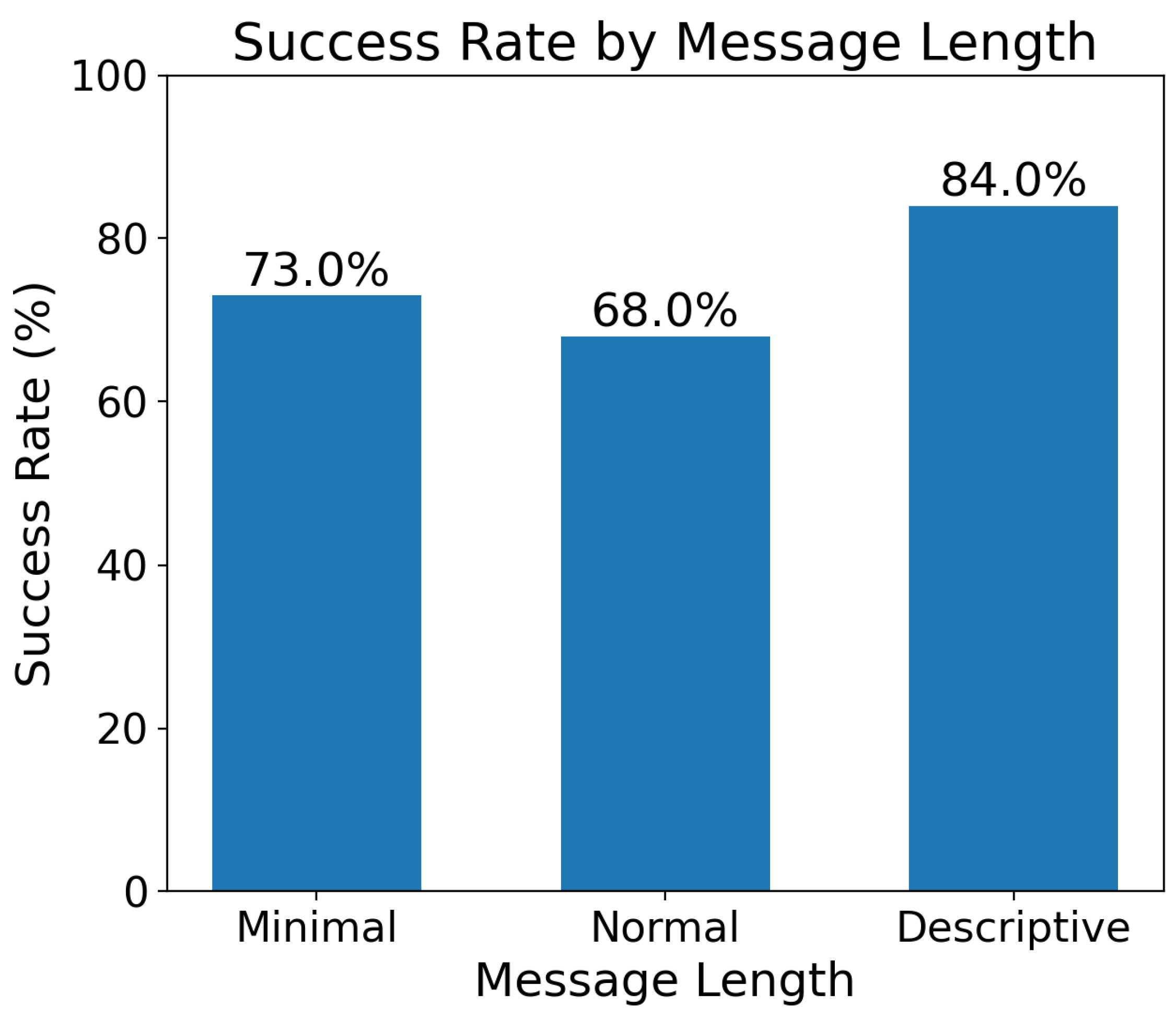

4.3. Result Analysis

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Work

5.3. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Kumar, P. Large language models (LLMs): survey, technical frameworks, and future challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 260.

- Liao, Y.; de Freitas Rocha Loures, E.; Deschamps, F. Industrial Internet of Things: A Systematic Literature Review and Insights. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 5, 4515–4525. [CrossRef]

- Flohr, L.A.; Kalinke, S.; Krüger, A.; Wallach, D.P. Chat or Tap? – Comparing Chatbots with ‘Classic’ Graphical User Interfaces for Mobile Interaction with Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Mobile Human-Computer Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2021; MobileHCI ’21. [CrossRef]

- Kassab, W.; Darabkh, K.A. A–Z survey of Internet of Things: Architectures, protocols, applications, recent advances, future directions and recommendations. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2020, 163, 102663. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) Models, 2023.

- Al-Qaseemi, S.A.; Almulhim, H.A.; Almulhim, M.F.; Chaudhry, S.R. IoT architecture challenges and issues: Lack of standardization. In Proceedings of the 2016 Future Technologies Conference (FTC), 2016, pp. 731–738. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.N.; Medvidovic, N.; Dashofy, E.M. Software Architecture: Foundations, Theory, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons, 2010; p. 736.

- Kadiyala, E.; Meda, S.; Basani, R.; Muthulakshmi, S. Global industrial process monitoring through IoT using Raspberry pi. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Nextgen Electronic Technologies: Silicon to Software (ICNETS2), 2017, pp. 260–262. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. CoRR 2017, abs/1706.03762, [1706.03762].

- Maddigan, P.; Susnjak, T. Chat2VIS: Generating Data Visualizations via Natural Language Using ChatGPT, Codex and GPT-3 Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45181–45193. [CrossRef]

- Vemprala, S.H.; Bonatti, R.; Bucker, A.; Kapoor, A. ChatGPT for Robotics: Design Principles and Model Abilities. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55682–55696. [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Blukis, V.; Mousavian, A.; Goyal, A.; Xu, D.; Tremblay, J.; Fox, D.; Thomason, J.; Garg, A. ProgPrompt: program generation for situated robot task planning using large language models. Autonomous Robots 2023, 47, 999–1012. [CrossRef]

- Driess, D.; Xia, F.; Sajjadi, M.S.M.; Lynch, C.; Chowdhery, A.; Ichter, B.; Wahid, A.; Tompson, J.; Vuong, Q.; Yu, T.; et al. PaLM-E: an embodied multimodal language model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning. JMLR.org, 2023, ICML’23.

- Kannan, S.S.; Venkatesh, V.L.N.; Min, B.C. SMART-LLM: Smart Multi-Agent Robot Task Planning using Large Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.RO/2309.10062].

- Wu, J.; Antonova, R.; Kan, A.; Lepert, M.; Zeng, A.; Song, S.; Bohg, J.; Rusinkiewicz, S.; Funkhouser, T. TidyBot: personalized robot assistance with large language models. Autonomous Robots 2023, 47, 1087–1102. [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Yu, H.; Lee, S.; Julien, C. Sasha: Creative Goal-Oriented Reasoning in Smart Homes with Large Language Models. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Petrović, N.; Koničanin, S.; Suljović, S. ChatGPT in IoT Systems: Arduino Case Studies. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Microelectronics (MIEL), 2023, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, N.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, M.; Shen, D.; Zhu, X. CASIT: Collective Intelligent Agent System for Internet of Things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 19646–19656. [CrossRef]

- Sarzaeim, P.; Mahmoud, Q.H.; Azim, A. A Framework for LLM-Assisted Smart Policing System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 74915–74929. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yue, Z. Building a Natural Language Query and Control Interface for IoT Platforms. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 68655–68668. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, G.; Cabot, J.; Deruelle, L.; Derras, M. Xatkit: A Multimodal Low-Code Chatbot Development Framework. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 15332–15346. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Dong, L.; Peng, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, K.; Pan, C.; Niyato, D.; Dobre, O.A. Large Language Model Enhanced Multi-Agent Systems for 6G Communications, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2312.07850].

- Chen, T.Y.; Chiu, Y.C.; Bi, N.; Tsai, R.T.H. Multi-Modal Chatbot in Intelligent Manufacturing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82118–82129. [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.A.; de Andrade, G.G.; Silva, G.R.S.; Duarte, F.C.M.; Costa, J.P.J.D.; de Sousa, R.T. A Conversation-Driven Approach for Chatbot Management. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 8474–8486. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Chrysostomou, D.; Yang, H. ToD4IR: A Humanised Task-Oriented Dialogue System for Industrial Robots. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 91631–91649. [CrossRef]

- Roller, S.; Dinan, E.; Goyal, N.; Ju, D.; Williamson, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ott, M.; Smith, E.M.; Boureau, Y.L.; et al. Recipes for Building an Open-Domain Chatbot. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume; Merlo, P.; Tiedemann, J.; Tsarfaty, R., Eds., Online, 2021; pp. 300–325. [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, A.S.; Van Steen, M. Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2002.

- Han, J.; E, H.; Le, G.; Du, J. Survey on NoSQL database. In Proceedings of the 2011 6th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Applications, 2011, pp. 363–366. [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, S.; Patil, M.; Patil, P. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing SQLite: Light Database System. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing 2015, 44, 882–885.

- Nikulchev, E.; Ilin, D.; Gusev, A. Technology Stack Selection Model for Software Design of Digital Platforms. Mathematics 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Team, R. React - A JavaScript library for building user interfaces. Meta Platforms, Inc., 2024.

- WorkOS. Radix UI, 2022. Open-source UI component library for building high-quality, accessible design systems and web apps.

- Labs, T. Tailwind CSS, 2023.

- Vercel. Next.js Documentation, 2024.

- Ronacher, A. Flask: Web Development, One Drop at a Time, 2024.

- Wings, E. Sensors and Modules, 2023.

- Smith, J.; Davis, M. Testing and Debugging IoT Projects with Raspberry Pi. Journal of Internet of Things 2020, 8, 123–135.

- Brown, M.; Green, S. Integrating Camera Modules with Raspberry Pi for Image Capture Applications. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2018, 64, 145–152.

- Wilkinson, B.; Allen, M. Parallel Programming: Techniques and Applications Using Networked Workstations and Parallel Computers, 2nd ed.; Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2005.

- Wytrębowicz, J.; Cabaj, K.; Krawiec, J. Messaging Protocols for IoT Systems—A Pragmatic Comparison. Sensors 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Wang, Y.; Chaturvedi, V.; Gupta, L.; Kim, S.; Kwon, Y.; Ha, S. LLMem: Estimating GPU Memory Usage for Fine-Tuning Pre-Trained LLMs, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2404.10933].

- Yang, H.; Yue, S.; He, Y. Auto-GPT for Online Decision Making: Benchmarks and Additional Opinions, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2306.02224].

- John, M.; Maurer, F.; Tessem, B. Human and social factors of software engineering. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Software Engineering, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, may 2005; p. 686. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Lee, C.P.; Mutlu, B. Understanding Large-Language Model (LLM)-powered Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2024; HRI ’24, p. 371–380. [CrossRef]

- Babar, M.; Zhu, L.; Jeffery, R. A framework for classifying and comparing software architecture evaluation methods. In Proceedings of the 2004 Australian Software Engineering Conference. Proceedings., 2004, pp. 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Ruman. Setting top-k, top-P and temperature in LLMS. https://rumn.medium.com/setting-top-k-top-p-and-temperature-in-llms-3da3a8f74832, 2024. Accessed: 19 August 2024.

| Symbol | Pin Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ULTS | Input | Ultrasonic distance sensor in ’cm’ |

| CAM | Input | Camera device for image acquisition |

| GPS | Input | GPS device for longitude and latitude coordinates |

| TMP | Input | Temperature sensor in degrees celsius |

| FAN | Output | 12V fan controlled through digital GPIO in relay |

| LCD | Output | LCD for displaying text data |

| SRV | Output | Servo motor rotates to given set of angles |

| LED1 | Output | Yellow LED light |

| LED2 | Output | Red LED light |

| LED3 | Output | Blue LED light |

| Function | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| set_led | Toggles specific LED | “Turn on yellow LED” |

| set_fan | Toggles fan on or off | “Turn on the fan” |

| get_recorded_sensor_data | Gets interval sensordata from database | “Plot me the distance data in last 30 seconds” |

| get_raspberry_stats | Gets CPU, RAM, disk of RPi | “What is the current disk usage” |

| capture_image | Capture and uploadimage to the cloud | “Capture an image, does it contain a pen?” |

| get_connected_devices | Fetches data of connected devices | “What is the current humidity and temperature” |

| get_location_ | Gets the current location from GPS | “From the location are we currently in Leeds?” |

| set_servo_angles | Turn servo to certain angle | “Turn the servo to 10 then 180 degrees” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).