Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

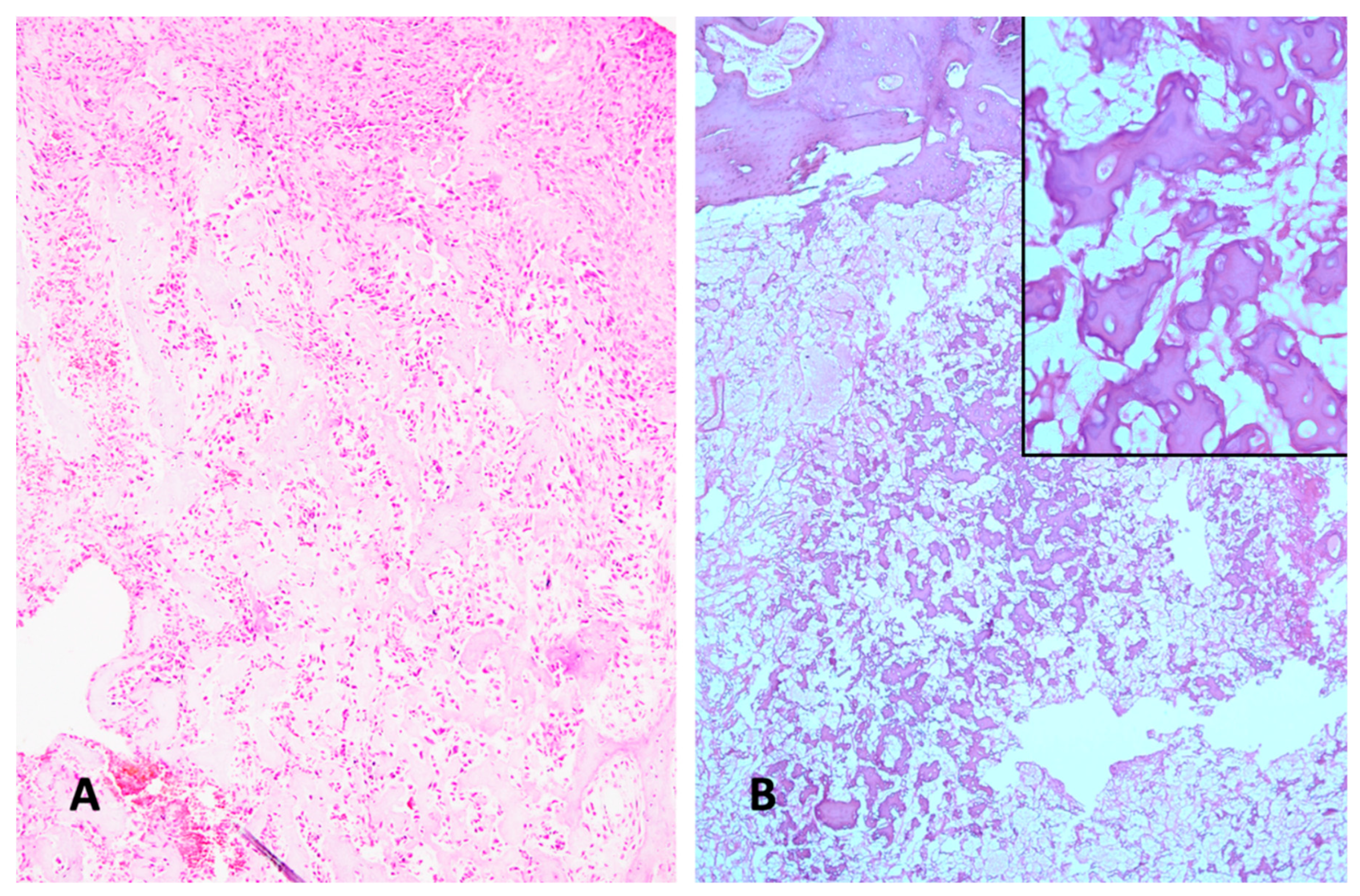

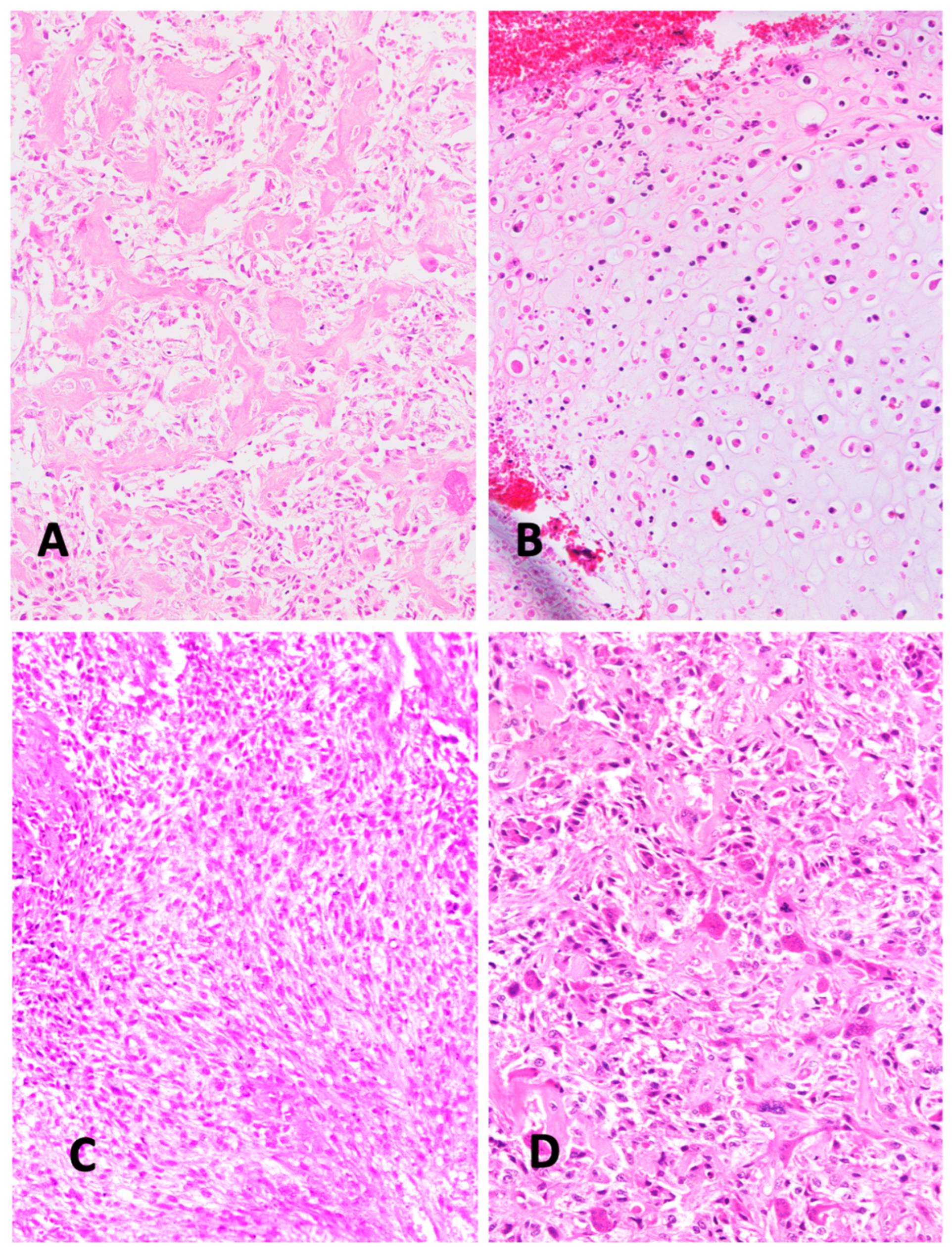

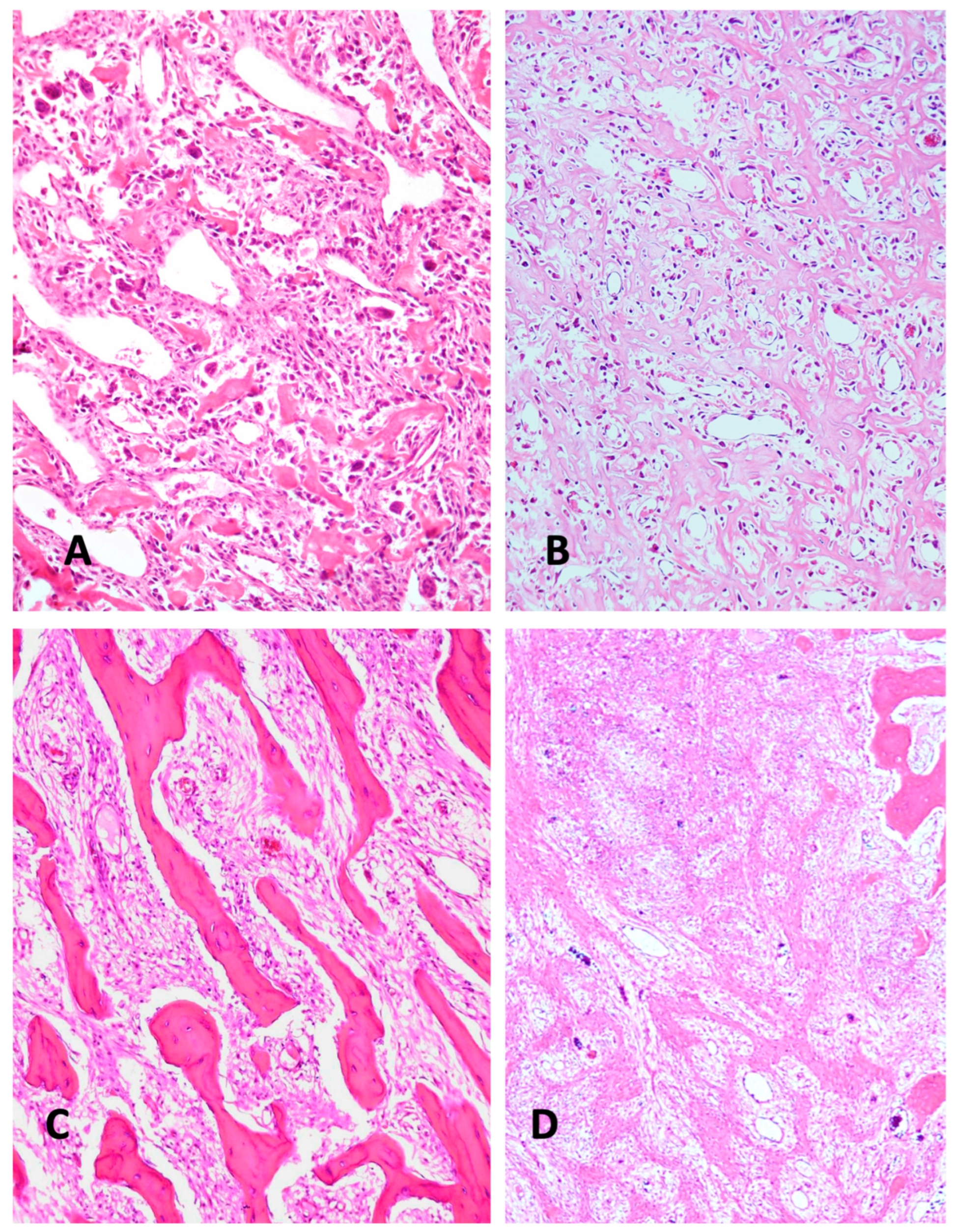

2. Histologic Characteristics

3. Molecular Genetic Characteristics

4. Challenges in Differential Diagnosis of Highly Malignant Osteosarcoma

5. NcRNAs in Translational Biology

Functions of regulatory ncRNAs in metazoan differentiation

Classification of ncRNAs, Basic Facts

6. NcRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Cancer

MiRNA as Tools in Cancer Diagnosis

LncRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Cancer

CircRNAs as diagnostic Biomarkers in cancer

Utility ncRNAs in Differentiating Benign and Malignant Tumors

7. NcRNAs as an Adjunct to Histological Differential Diagnosis of Highly Malignant Osteosarcoma

8. NcRNAs as General Diagnostic Biomarkers for Highly Malignant Osteosarcoma

9. Possibilities of ncRNAs for Prediction Chemotherapy Response

Cell culture studies

Clinical studies

| Non coding RNA | Materials | Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-34a | Serum | Negatively associated with chemotherapy resistance of OS patients. | Lian H et al. [167] |

| miRNA-22 | Plasma | Low plasma miR-22 level were corre- lated with poor tumor response to preoperative chemotherapy. |

Diao ZB et al. [168] |

| miRNA-375 | Serum | low serum miR 375 level was significantly associated with poor tumor response to chemotherapy | Liu W et al. [169] |

| miRNA-132 | Sarcoma tissue, fresh frozen |

miR-132 expression was decreased in the osteosarcoma specimens with poor response to chemotherapy. | Yang J et al. [173] |

| miRNA-21 | Serum | High serum miR-21 was significantly correlated with advanced Enneking stage and chemotherapeutic resistance. |

Yuan J et al. [174] |

| miRNA-21 | Serum | The expression level of serum miR-21 in patients with osteosarcoma is closely related to the therapeutic effects of osteosarcoma. |

Hua Y et al. [175] |

| miR-92a, miR-99b, miR-132, miR-193a-5p miR-422a | Sarcoma tissue, FFPE | miRNAs miR-92a, miR-99b, miR-132, miR-193a-5p and miR-422a could discriminate good from bad responders. | Gougelet A et al. [176] |

10. NcRNAs and Prediction of Metastatic Risk

11. Concluding Remarks

Declaration of Interest

Author Contributions

References

- Yoshida, A. Osteosarcoma. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2021, 14, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, S.A.; Mirabello, L. Using Epidemiology and Genomics to Understand Osteosarcoma Etiology. Sarcoma 2011, 2011, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, A.; Matsumoto, S.; Kawai, A.; Okuma, T.; Hiraga, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Yonemoto, T.; Hosaka, M.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Osteosarcoma in patients over 50 years of age: Multi-institutional retrospective analysis of 104 patients. J. Orthop. Sci. 2020, 25, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumhoer, D.; Brunner, P.; Eppenberger-Castori, S.; Smida, J.; Nathrath, M.; Jundt, G. Osteosarcomas of the jaws differ from their peripheral counterparts and require a distinct treatment approach. Experiences from the DOESAK Registry. Oral Oncol. 2014, 50, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.J.; Davis, E.J. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Adults with Osteogenic Sarcoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielack, S.S.; Kempf-Bielack, B.; Delling, G.; Exner, G.U.; Flege, S.; Helmke, K.; Kotz, R.; Salzer-Kuntschik, M.; Werner, M.; Winkelmann, W.; et al. Prognostic Factors in High-Grade Osteosarcoma of the Extremities or Trunk: An Analysis of 1,702 Patients Treated on Neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group Protocols. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kager, L.; Zoubek, A.; Pötschger, U.; Kastner, U.; Flege, S.; Kempf-Bielack, B.; Branscheid, D.; Kotz, R.; Salzer-Kuntschik, M.; Winkelmann, W.; et al. Primary Metastatic Osteosarcoma: Presentation and Outcome of Patients Treated on Neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group Protocols. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer-Kuntschik, M.; Delling, G.; Beron, G.; Sigmund, R. Morphological grades of regression in osteosarcoma after polychemotherapy ? Study COSS 80. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1983, 106, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.; Bertoni, F.; Longhi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Forni, C.; Biagini, R.; Bacchini, P.; Donati, D.; Manfrini, M.; Bernini, G.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-grade central osteosarcoma of the extremity. Cancer 2003, 97, 3068–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.T.; Mills, A.M. Osteogenic tumors of bone. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 31, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansara, M.; Teng, M.W.; Smyth, M.J.; Thomas, D.M. Translational biology of osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickel, K.; Fang, F.; Tao, J. Molecular genetics of osteosarcoma. Bone 2017, 102, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cè, M.; Cellina, M.; Ueanukul, T.; Carrafiello, G.; Manatrakul, R.; Tangkittithaworn, P.; Jaovisidha, S.; Fuangfa, P.; Resnick, D. Multimodal Imaging of Osteosarcoma: From First Diagnosis to Radiomics. Cancers 2025, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, N.; Lam, S.W.; Cleton-Jansen, A.-M.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. What’s new in bone forming tumours of the skeleton? Virchows Arch. 2019, 476, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhong, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, J. Non-coding RNAs as potential biomarkers in osteosarcoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1028477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, A.J.; Walkley, C.R. Cells of origin in osteosarcoma: Mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblast committed cells? Bone 2014, 62, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.J.; Siegal, G.P. Osteosarcoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 125, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, M.H.; Kandel, R.A.; Wong, M.; Griffin, A.M.; Bell, R.S.; Blackstein, M.E.; Wunder, J.S.; Dickson, B.C.; Michael Herman Chui, MD; Rita A. Kandel, MD; Marcus Wong, BSc; Anthony M. Griffin, MSc; Robert S. Bell, MD; Martin E. Blackstein, MD, PhD; Jay S. Wunder, MD, MSc; Brendan C. Dickson, MD, MScFrom the Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; Md; et al. Histopathologic Features of Prognostic Significance in High-Grade Osteosarcoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Miller, C.; Koeffler, H.P.; Battifora, H.; Cline, M.J. Rearrangement of the p53 gene in human osteogenic sarcomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987, 84, 7716–7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toguchida, J.; Ishizaki, K.; Sasaki, M.S.; Nakamura, Y.; Ikenaga, M.; Kato, M.; Sugimot, M.; Kotoura, Y.; Yamamuro, T. Preferential mutation of paternally derived RB gene as the initial event in sporadic osteosarcoma. Nature 1989, 338, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bahrami, A.; Pappo, A.; Easton, J.; Dalton, J.; Hedlund, E.; Ellison, D.; Shurtleff, S.; Wu, G.; Wei, L.; et al. Recurrent Somatic Structural Variations Contribute to Tumorigenesis in Pediatric Osteosarcoma. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behjati, S.; Tarpey, P.S.; Haase, K.; Ye, H.; Young, M.D.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Farndon, S.J.; Collord, G.; Wedge, D.C.; Martincorena, I.; et al. Recurrent mutation of IGF signalling genes and distinct patterns of genomic rearrangement in osteosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15936–15936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, M.; Noirot, C.; Accadbled, F.; de Gauzy, J.S.; Castex, M.; Brousset, P.; Gomez-Brouchet, A. Whole-exome sequencing in osteosarcoma reveals important heterogeneity of genetic alterations. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, C.; Mancini, M.; Lessi, F.; Aretini, P.; De Gregorio, V.; Puggioni, C.; Carletti, R.; Petrozza, V.; Civita, P.; Franceschi, S.; et al. Whole-exome analysis in osteosarcoma to identify a personalized therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 80416–80428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, M.; Blattmann, C.; Ribi, S.; Smida, J.; Mueller, N.S.; Engert, F.; Castro-Giner, F.; Weischenfeldt, J.; Kovacova, M.; Krieg, A.; et al. Exome sequencing of osteosarcoma reveals mutation signatures reminiscent of BRCA deficiency. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8940–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.A.; Kiezun, A.; Tonzi, P.; Van Allen, E.M.; Carter, S.L.; Baca, S.C.; Cowley, G.S.; Bhatt, A.S.; Rheinbay, E.; Pedamallu, C.S.; et al. Complementary genomic approaches highlight the PI3K/mTOR pathway as a common vulnerability in osteosarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, E5564–E5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing JR, Wilson RK, Zhang J, Mardis ER, Pui C-H, Ley TiJ, et al. The Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Nat Genet 2013; 44:619–22. [CrossRef]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 2011, 144, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik-Zainal, S.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Wedge, D.C.; Van Loo, P.; Greenman, C.D.; Raine, K.; Jones, D.; Hinton, J.; Marshall, J.; Stebbings, L.A.; et al. Mutational Processes Molding the Genomes of 21 Breast Cancers. Cell 2012, 149, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik-Zainal, S.; Davies, H.; Staaf, J.; Ramakrishna, M.; Glodzik, D.; Zou, X.; Martincorena, I.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Martin, S.; Wedge, D.C.; et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 2016, 534, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smida, J.; Baumhoer, D.; Rosemann, M.; Walch, A.; Bielack, S.; Poremba, C.; Remberger, K.; Korsching, E.; Scheurlen, W.; Dierkes, C.; et al. Genomic Alterations and Allelic Imbalances Are Strong Prognostic Predictors in Osteosarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 4256–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amary, M.F.; Bacsi, K.; Maggiani, F.; Damato, S.; Halai, D.; Berisha, F.; Pollock, R.; O'Donnell, P.; Grigoriadis, A.; Diss, T.; et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J. Pathol. 2011, 224, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zöllner, S.K.; Amatruda, J.F.; Bauer, S.; Collaud, S.; de Álava, E.; DuBois, S.G.; Hardes, J.; Hartmann, W.; Kovar, H.; Metzler, M.; et al. Ewing Sarcoma—Diagnosis, Treatment, Clinical Challenges and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suehara, Y.; Alex, D.; Bowman, A.; Middha, S.; Zehir, A.; Chakravarty, D.; Wang, L.; Jour, G.; Nafa, K.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Clinical Genomic Sequencing of Pediatric and Adult Osteosarcoma Reveals Distinct Molecular Subsets with Potentially Targetable Alterations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6346–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumhoer, D.; Hench, J.; Amary, F. Recent advances in molecular profiling of bone and soft tissue tumors. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.W.; van Ijzendoorn, D.G.; Cleton-Jansen, A.-M.; Szuhai, K.; Bovée, J.V. Molecular Pathology of Bone Tumors. J. Mol. Diagn. 2019, 21, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumhoer, D.; Amary, F.; Flanagan, A.M. An update of molecular pathology of bone tumors. Lessons learned from investigating samples by next generation sequencing. Genes, Chromosom. Cancer 2018, 58, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonmuang, S.; Chaiyawat, P.; Jantrapirom, S.; Pruksakorn, D.; Piccolo, L.L. Circulating Long Non-Coding RNAs as Novel Potential Biomarkers for Osteogenic Sarcoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Skipar, P.; Bartnik, E.; Piątkowski, J.; Sulejczak, D.; Czarnecka, A.M. MicroRNA signatures in osteosarcoma: diagnostic insights and therapeutic prospects. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 480, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Wang, J. Emerging Roles of Circular RNAs in Osteosarcoma. Med Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 7043–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, Y.; Asano, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Abe, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; et al. A validation study for the utility of serum microRNA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in patients with osteosarcoma. Oncol. Lett. 2023, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ENCODE Project Consortium. An Integrated Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in the Human Genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beermann, J.; Piccoli, M.-T.; Viereck, J.; Thum, T. Non-coding RNAs in Development and Disease: Background, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Approaches. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1297–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, P.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; De La Vega, F.M.; Faial, T.; Frankish, A.; Gingeras, T.; Guigo, R.; Harrow, J.L.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G.; Johnson, R.; et al. The status of the human gene catalogue. Nature 2023, 622, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Makunin, I.V. Non-coding RNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, R17–R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Simakov, O.; Chapman, J.; Fahey, B.; Gauthier, M.E.A.; Mitros, T.; Richards, G.S.; Conaco, C.; Dacre, M.; Hellsten, U.; et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature 2010, 466, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J. Regulatory RNAs and the demise of 'junk' DNA. Genome Biol. 2006, 7, 328–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willingham, A.T.; Gingeras, T.R. TUF Love for “Junk” DNA. Cell 2006, 125, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Vincent, K.; Pichler, M.; Fodde, R.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Slack, F.J.; Calin, G.A. Junk DNA and the long non-coding RNA twist in cancer genetics. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5003–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerkandl, E. Revisiting junk DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 1992, 34, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S. A Kuhnian revolution in molecular biology: Most genes in complex organisms express regulatory RNAs. BioEssays 2023, 45, e2300080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, T.R.; Steitz, J.A. The Noncoding RNA Revolution—Trashing Old Rules to Forge New Ones. Cell 2014, 157, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, JS. Non-coding RNAs : the architects of eukaryotic complexity 2001; 2:986–91.

- Yang, J.X.; Rastetter, R.H.; Wilhelm, D. Non-coding RNAs: An introduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016; 886, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

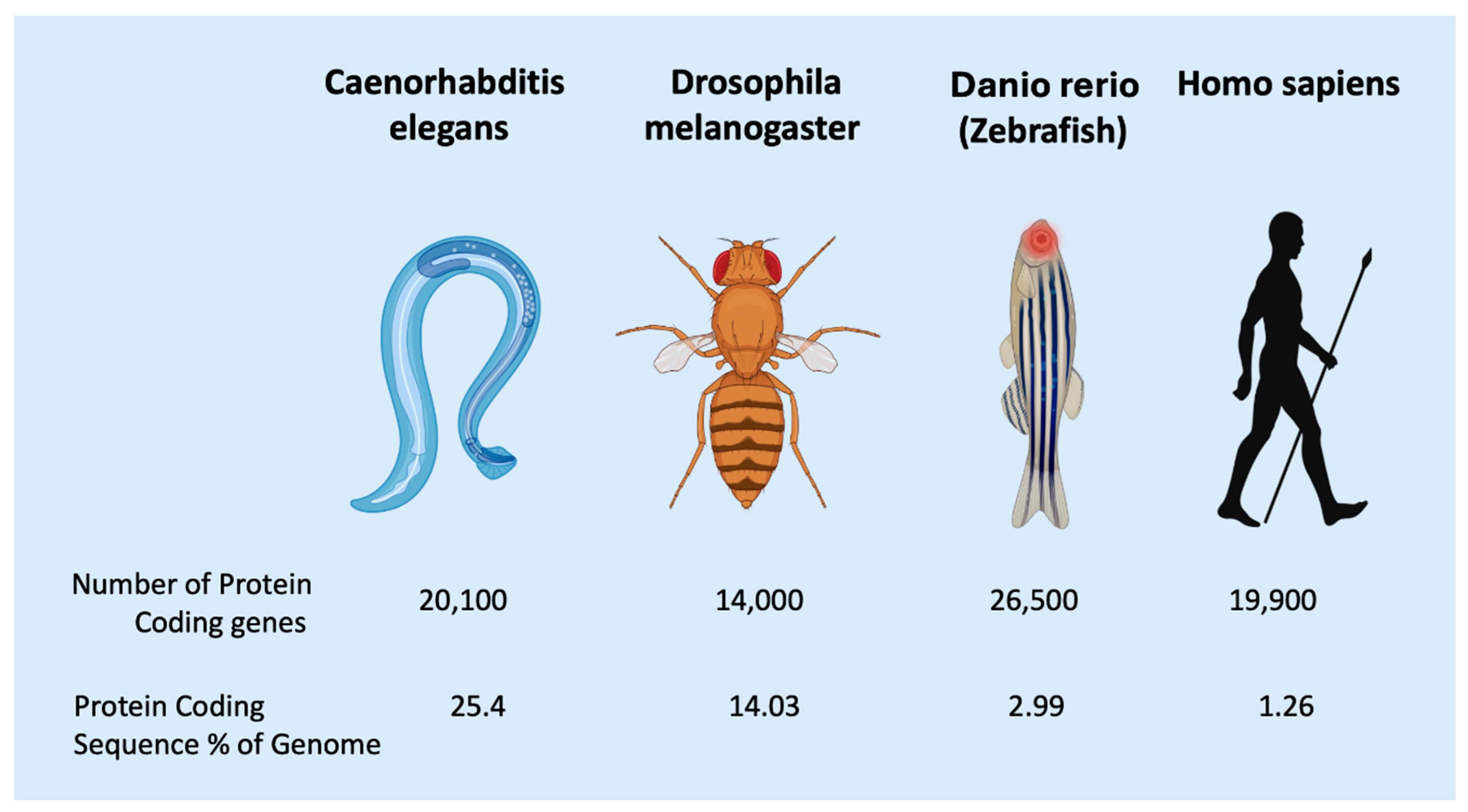

- Taft, R.J.; Pheasant, M.; Mattick, J.S. The relationship between non-protein-coding DNA and eukaryotic complexity. BioEssays 2007, 29, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, K.V.; Mattick, J.S. The rise of regulatory RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, J.S. The central role of RNA in human development and cognition. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 1600–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiti, F.; Calcino, A.D.; Tanurdžić, M.; Degnan, B.M. Origin and evolution of the metazoan non-coding regulatory genome. Dev. Biol. 2017, 427, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveley, BR. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world 2001; 17:100–7.

- Nurk, S.; Koren, S.; Rhie, A.; Rautiainen, M.; Bzikadze, A.V.; Mikheenko, A.; Vollger, M.R.; Altemose, N.; Uralsky, L.; Gershman, A.; et al. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science 2022, 376, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S. RNA out of the mist. Trends Genet. 2022, 39, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, R.J.; Pheasant, M.; Mattick, J.S. The relationship between non-protein-coding DNA and eukaryotic complexity. BioEssays 2007, 29, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018, 173, 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mattick, J.S.; Taft, R.J. A meta-analysis of the genomic and transcriptomic composition of complex life. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA: trends in clinical trials of cancer diagnosis and therapy strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Leva, G.; Croce, C.M. miRNA profiling of cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2013, 23, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, P.; Du, X. The long non-coding RNAs, a new cancer diagnostic and therapeutic gold mine. Mod. Pathol. 2013, 26, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, S.E.; Martienssen, R.A. RNA interference in the nucleus: roles for small RNAs in transcription, epigenetics and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tétreault, N.; De Guire, V. miRNAs: Their discovery, biogenesis and mechanism of action. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 46, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Bernard, P.S.; Perou, C.M. Molecular portraits and the family tree of cancer. Nat. Genet. 2002, 32, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.L.; Settleman, J. From Cancer Genomics to Precision Oncology—Tissue’s Still an Issue. Cell 2014, 157, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Mays, J.C.; Davoli, T. Not all cancers are created equal: Tissue specificity in cancer genes and pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 63, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, K.A.; Yau, C.; Hinoue, T.; Wolf, D.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Drill, E.; Shen, R.; Taylor, A.M.; Cherniack, A.D.; Thorsson, V.; et al. Cell-of-Origin Patterns Dominate the Molecular Classification of 10,000 Tumors from 33 Types of Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 291–304.e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansinho, A.; Fernandes, R.M.; Carneiro, A.V. Histology-Agnostic Drugs: A Paradigm Shift—A Narrative Review. Adv. Ther. 2022, 40, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Feng, G. Digitalization and third-party logistics performance: Exploring the roles of customer collaboration and government. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2023, 53, 467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Gaiti, F.; Fernandez-Valverde, S.L.; Nakanishi, N.; Calcino, A.D.; Yanai, I.; Tanurdzic, M.; Degnan, B.M. Dynamic and Widespread lncRNA Expression in a Sponge and the Origin of Animal Complexity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2367–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrat, C.E.; Thompson, D.C.; Barbu, M.G.; Bugnar, O.L.; Boboc, A.; Cretoiu, D.; Suciu, N.; Cretoiu, S.M.; Voinea, S.C. miRNAs as Biomarkers in Disease: Latest Findings Regarding Their Role in Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cells 2020, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Leidinger, P.; Becker, K.; Backes, C.; Fehlmann, T.; Pallasch, C.; Rheinheimer, S.; Meder, B.; Stähler, C.; Meese, E.; et al. Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 3865–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shademan, B.; Karamad, V.; Nourazarian, A.; Masjedi, S.; Isazadeh, A.; Sogutlu, F.; Avcı, C.B. MicroRNAs as Targets for Cancer Diagnosis: Interests and Limitations. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 13, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, E.; Jacob, L.S.; Slack, F.J. Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, E.; Faggioni, A.; Trivedi, P.; Slack, F.J. The Nefarious Nexus of Noncoding RNAs in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, R.; Wang, J.; Qin, Z.; Xue, L. Circulating microRNAs as potential cancer biomarkers: the advantage and disadvantage. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zen, K.; Zhang, C.-Y. Horizontal transfer of microRNAs: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Protein Cell 2012, 3, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyamala, K.; Girish, H.; Murgod, S. Risk of tumor cell seeding through biopsy and aspiration cytology. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2014, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołat, D.; Hammouz, R.; Bednarek, A.K.; Płuciennik, E. Exosomes as carriers transporting long non-coding RNAs: Molecular characteristics and their function in cancer (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behulová, R.L.; Bugalová, A.; Bugala, J.; Struhárňanská, E.; Šafranek, M.; Juráš, I. Circulating Exosomal miRNAs as a Promising Diagnostic Biomarker in Cancer. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, S193–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: cancer screening and early detection. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapisz, D. The first liquid biopsy test approved. Is it a new era of mutation testing for non-small cell lung cancer? Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 46–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tétreault, N.; De Guire, V. miRNAs: Their discovery, biogenesis and mechanism of action. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 46, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA: trends in clinical trials of cancer diagnosis and therapy strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, C.L.; Tsongalis, G.J. MicroRNAs: Novel Biomarkers for Human Cancer. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crim, J.; Layfield, L.J. Bone and soft tissue tumors at the borderlands of malignancy. Skelet. Radiol. 2022, 52, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, E.; Pyman, B.; Nanayakkara, J.; Tuschl, T.; Tyryshkin, K.; Renwick, N.; Mousavi, P. Discriminating Neoplastic from Nonneoplastic Tissues Using an miRNA-Based Deep Cancer Classifier. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 192, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, J.S. The State of Long Non-Coding RNA Biology. Non-Coding RNA 2018, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.B.; Mattick, J.S. Long noncoding RNAs in cell biology. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Yang, J. Long Non-Coding RNA in the Pathogenesis of Cancers. Cells 2019, 8, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, M.K.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Malik, R.; Singhal, U.; Sahu, A.; Hosono, Y.; Barrette, T.R.; Prensner, J.R.; Evans, J.R.; Zhao, S.; et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Zhu, J.; Hu, H.-B.; Liu, J.-Q. Circular RNAs: Promising biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Gene 2021, 771, 145365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisignano, G.; Michael, D.C.; Visal, T.H.; Pirlog, R.; Ladomery, M.; Calin, G.A. Going circular: history, present, and future of circRNAs in cancer. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2783–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Li, T.; Xiao, B.; Sun, W. The biogenesis and biological functions of circular RNAs and their molecular diagnostic values in cancers. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 34, e23049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Su, W.; Liu, L.; Rao, B.; Lin, M.; Feng, Y.; Qiu, F.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Identification of Three Circular RNA Cargoes in Serum Exosomes as Diagnostic Biomarkers of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the Chinese Population. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Qin, J.; Liu, X.; He, B.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y.; Sun, H.; Xu, T.; Xu, M.; Chen, X.; et al. Identification of Serum Exosomal hsa-circ-0004771 as a Novel Diagnostic Biomarker of Colorectal Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, J.; Tang, Y.; Tian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Circular RNAs in Cancer: emerging functions in hallmarks, stemness, resistance and roles as potential biomarkers. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Mayer, T.; Johnstone, B.; Les, C.; Frisch, N.; Parsons, T.; Mi, Q.-S.; Gibson, G. Use of MicroRNA biomarkers to distinguish enchondroma from low-grade chondrosarcoma. Connect. Tissue Res. 2016, 58, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Russo, G.I.; Leonardi, R.; Carcò, D.; Gattuso, G.; Falzone, L.; Ferrara, C.; Caponnetto, A.; Battaglia, R.; Libra, M.; et al. Extracellular RNAs from Whole Urine to Distinguish Prostate Cancer from Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielak, C.; Arya, A.; Savill, S. Circulating microRNA as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of well-differentiated thyroid cancer: A review article. Cancer Biomarkers 2023, 36, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Kamal, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Najafi, H.; Zarchi, A.S.; Haddad, P.; Shayestehpour, B.; Kamkar, L.; Salamati, M.; Geranpayeh, L.; et al. A novel panel of blood-based microRNAs capable of discrimination between benign breast disease and breast cancer at early stages. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, V.S.; Nasu, M.; Deng, Y.; Jijiwa, M. Circulating microRNA Biomarker for Detecting Breast Cancer in High-Risk Benign Breast Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burenina, O.Y.; Lazarevich, N.L.; Kustova, I.F.; Shavochkina, D.A.; Moroz, E.A.; Kudashkin, N.E.; Patyutko, Y.I.; Metelin, A.V.; Kim, E.F.; Skvortsov, D.A.; et al. Panel of potential lncRNA biomarkers can distinguish various types of liver malignant and benign tumors. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 147, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués, M.; Pont, M.; Hidalgo, I.; Sorolla, M.A.; Parisi, E.; Salud, A.; Sorolla, A.; Porcel, J.M. MicroRNAs Present in Malignant Pleural Fluid Increase the Migration of Normal Mesothelial Cells In Vitro and May Help Discriminate between Benign and Malignant Effusions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolivet, E.; Gaichies, L.; Jeanne, C.; Bazille, C.; Briand, M.; Vernon, M.; Giffard, F.; Leprêtre, F.; Poulain, L.; Denoyelle, C.; et al. Synergy of the microRNA Ratio as a Promising Diagnosis Biomarker for Mucinous Borderline and Malignant Ovarian Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, K.J.; Helwig, J.; Bertram, S.; Sheu, S.Y.; Suttorp, A.C.; Seggewiß, J.; Willscher, E.; Walz, M.K.; Worm, K.; Schmid, K.W. Differential expression of microRNA-675, microRNA-139-3p and microRNA-335 in benign and malignant adrenocortical tumours. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecker-Nolting, S.; Baumhoer, D.; Blattmann, C.; Kager, L.; Kühne, T.; Kevric, M.; Lang, S.; Mettmann, V.; Sorg, B.; Werner, M.; et al. Osteosarcoma pre-diagnosed as another tumor: a report from the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group (COSS). J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 149, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suster, D.; Mackinnon, A.C.; Jarzembowski, J.A.; Carrera, G.; Suster, S.; Klein, M.J. Epithelioid osteoblastoma. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2022, 125, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarotti, M.; Tos, A.P.D.; Vanel, D.; Picci, P.; Gibertoni, D.; Klein, M.J.; Righi, A. Osteoblastoma-like osteosarcoma: high-grade or low-grade osteosarcoma? Histopathology 2018, 74, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fittall, M.W.; Mifsud, W.; Pillay, N.; Ye, H.; Strobl, A.-C.; Verfaillie, A.; Demeulemeester, J.; Zhang, L.; Berisha, F.; Tarabichi, M.; et al. Recurrent rearrangements of FOS and FOSB define osteoblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.W.; Cleven, A.H.G.; Kroon, H.M.; Bruijn, I.H.B.-D.; Szuhai, K.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. Utility of FOS as diagnostic marker for osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. Virchows Arch. 2019, 476, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amary, F.; Markert, E.; Berisha, F.; Ye, H.; Gerrand, C.; Cool, P.; Tirabosco, R.; Lindsay, D.; Pillay, N.; O’donnell, P.; et al. FOS Expression in Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameline, B.; Nathrath, M.; Nord, K.H.; de Flon, F.H.; Bovée, J.V.; Krieg, A.H.; Höller, S.; Hench, J.; Baumhoer, D. Methylation and copy number profiling: emerging tools to differentiate osteoblastoma from malignant mimics? Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riester, S.M.; Torres-Mora, J.; Dudakovic, A.; Camilleri, E.T.; Wang, W.; Xu, F.; Thaler, R.R.; Evans, J.M.; Zwartbol, R.; Bruijn, I.H.B.-D.; et al. Hypoxia-related microRNA-210 is a diagnostic marker for discriminating osteoblastoma and osteosarcoma. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 35, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmini, G.; Brandi, M.L. microRNAs and bone tumours: Role of tiny molecules in the development and progression of chondrosarcoma, of giant cell tumour of bone and of Ewing's sarcoma. Bone 2021, 149, 115968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.; Wei, P. Clinical Value of Differential lncRNA Expressions in Diagnosis of Giant Cell Tumor of Bone and Tumor Recurrence. Clin. Lab. 2020, 66, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; He, N.; Yan, H.; Dong, Y. Characterization of MicroRNA Expression Profiles in Patients with Giant Cell Tumor. Orthop. Surg. 2016, 8, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, K.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, L. Network study of miRNA regulating traumatic heterotopic ossification. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0318779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewski, B.; Pulik, Ł.; Grabowska, I.; Sibilska, A.; Ciemerych, M.A.; Łęgosz, P.; Brzoska, E. Coding and noncoding RNA profile of human heterotopic ossifications - Risk factors and biomarkers. Bone 2023, 176, 116883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, Y.; Asano, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Abe, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; et al. A validation study for the utility of serum microRNA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in patients with osteosarcoma. Oncol. Lett. 2023, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Ye, Z. Identification of Serum miR-337-3p, miR-484, miR-582, and miR-3677 as Promising Biomarkers for Osteosarcoma. Clin. Lab. 2021, 67, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, H.; Huang, A. MiR-429 and MiR-143-3p Function as Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers for Osteosarcoma. Clin. Lab. 2020, 66, 1945–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Xiang, L. Up-Regulation of circRNA hsa_circ_0003074 Expression is a Reliable Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 9315–9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.-S.; Li, C.; Liang, D.; Jiang, X.-B.; Tang, J.-J.; Ye, L.-Q.; Yuan, K.; Ren, H.; Yang, Z.-D.; Jin, D.-X.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of serum miR-101 in osteosarcoma. Cancer Biomarkers 2018, 22, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.; Wang, W.; Tian, J.; Gao, T.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, C. Identification of serum miR-124 as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis in osteosarcoma. Cancer Biomarkers 2018, 21, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Q.; Niu, D.; Liu, B. Serum miR-95-3p is a diagnostic and prognostic marker for osteosarcoma. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Liao, W.; Liu, R.; Shi, P.; Wang, L. miRNA-223 is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for osteosarcoma. J. Bone Oncol. 2016, 5, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, F.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, C.; Gao, K.; Wu, L. Identification of a Plasma Four-microRNA Panel as Potential Noninvasive Biomarker for Osteosarcoma. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121499–e0121499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Qi, B.; Sun, X. Serum microRNA-221 functions as a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for patients with osteosarcoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 75, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen G, Caparros B, Huvos AG, Kosloff C, Nirenberg A, Cacavio A, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: Selection of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy based on the response of the primary tumor to preoperative chemotherapy. Cancer 1982; 49:1221–30. [CrossRef]

- Glasser DB, Lane JM, Huvos AG, Marcove RC, Rosen G. Survival, prognosis, and therapeutic response in osteogenic sarcoma. The memorial hospital experience. Cancer 1992; 69:698–708. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Bell, R.S.; Goodwin, P. Prognostic factors in osteosarcoma: A critical review. J. Clin. Oncol. 1994, 12, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’kane, G.M.; A Cadoo, K.; Walsh, E.M.; Emerson, R.; Dervan, P.; O’keane, C.; Hurson, B.; O’toole, G.; Dudeney, S.; Kavanagh, E.; et al. Perioperative chemotherapy in the treatment of osteosarcoma: a 26-year single institution review. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.J.; Agaram, N.P.; Jean, M.-H.; Suser, S.D.; Chu, C.; Vanderbilt, C.M.; Meyers, P.A.; Wexler, L.H.; Healey, J.H.; Fuchs, T.J.; et al. Deep Learning–Based Objective and Reproducible Osteosarcoma Chemotherapy Response Assessment and Outcome Prediction. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 193, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, C.; Mancini, M.; Lessi, F.; Aretini, P.; De Gregorio, V.; Puggioni, C.; Carletti, R.; Petrozza, V.; Civita, P.; Franceschi, S.; et al. Whole-exome analysis in osteosarcoma to identify a personalized therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 80416–80428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, B.H.; Kong, C.-B.; Lim, I.; Kim, B.I.; Choi, C.W.; Song, W.S.; Cho, W.H.; Jeon, D.-G.; Koh, J.-S.; Lee, S.-Y.; et al. Early response monitoring to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in osteosarcoma using sequential 18 F-FDG PET/CT and MRI. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 41, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, S.; Takeuchi, A.; Shirai, T.; Taki, J.; Yamamoto, N.; Nishida, H.; Hayashi, K.; Tanzawa, Y.; Kimura, H.; Igarashi, K.; et al. Prognostic Value of Radiological Response to Chemotherapy in Patients with Osteosarcoma. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laux, C.J.; Berzaczy, G.; Weber, M.; Lang, S.; Dominkus, M.; Windhager, R.; Nöbauer-Huhmann, I.-M.; Funovics, P.T. Tumour response of osteosarcoma to neoadjuvant chemotherapy evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging as prognostic factor for outcome. Int. Orthop. 2014, 39, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Cheng, W.-T.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.-L.; Deng, S.-S.; Li, J.; Yang, C.-H. Comprehensive Analysis of Key mRNAs and lncRNAs in Osteosarcoma Response to Preoperative Chemotherapy with Prognostic Values. Curr. Med Sci. 2021, 41, 916–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrle, D.; Bielack, S.S. Current strategies of chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Int. Orthop. 2006, 30, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S.; Errani, C.; Angelini, A.; Mavrogenis, A.F. Current Treatment Considerations for Osteosarcoma Metastatic at Presentation. Orthopedics 2020, 43, E345–E358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xie, X.; Lu, S.; Liu, T. Noncoding RNAs in osteosarcoma: Implications for drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 2021, 504, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Xu, R.; Xu, Y. miR-29 Family Inhibits Resistance to Methotrexate and Promotes Cell Apoptosis by Targeting COL3A1 and MCL1 in Osteosarcoma. Med Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 8812–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhu, Y. Effect of lncRNA ANRIL knockdown on proliferation and cisplatin chemoresistance of osteosarcoma cells in vitro. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2019, 215, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yan, X. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 promotes cisplatin-chemosensitivity of osteosarcoma cells via microRNA-26b-5p/TP53INP1 axis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Qu, F. CircUBAP2 promotes SEMA6D expression to enhance the cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma through sponging miR-506-3p by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Histochem. J. 2020, 51, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, F.; Zhou, R.; Xu, J.; Xiao, J.; Dai, F.; Song, L. Circular RNA circ-CHI3L1.2 modulates cisplatin resistance of osteosarcoma cells via the miR-340-5p/LPAATβ axis. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Dou, D.; Zhang, T.; Wang, B. HOTAIR Promotes Cisplatin Resistance of Osteosarcoma Cells by Regulating Cell Proliferation, Invasion, and Apoptosis via miR-106a-5p/STAT3 Axis. Cell Transplant. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Fan, G.; Yao, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y. MicroRNA-150 functions as a tumor suppressor and sensitizes osteosarcoma to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by targeting RUNX2. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 19, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ding, R.; Fu, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, W.; Si, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Overexpression of miR-506-3p reversed doxorubicin resistance in drug-resistant osteosarcoma cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1303732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Y. Hsa_circ_0004674 promotes osteosarcoma doxorubicin resistance by regulating the miR-342-3p/FBN1 axis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Li, S. Unraveling the impact of noncoding RNAs in osteosarcoma drug resistance: a review of mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 111, 2112–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ni, J.; Huang, J. Molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance in osteosarcoma (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Han, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, S. LncRNAs as potential prognosis/diagnosis markers and factors driving drug resistance of osteosarcoma, a review. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1415722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Han, Y. Deciphering chemoresistance in osteosarcoma: Unveiling regulatory mechanisms and function through the lens of noncoding RNA. Drug Dev. Res. 2024, 85, e22167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. Drug resistance-related microRNAs in osteosarcoma: Translating basic evidence into therapeutic strategies. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.B.; Zhou, Y.B.; Sun, Z.B.; Liu, K.B. MicroRNA34a is associated with chemotherapy resistance, metastasis, recurrence, survival, and prognosis in patient with osteosarcoma. Medicine 2022, 101, e30722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Z.-B.; Sun, T.-X.; Zong, Y.; Lin, B.-C.; Xia, Y.-S. Identification of plasma microRNA-22 as a marker for the diagnosis, prognosis, and chemosensitivity prediction of osteosarcoma. J. Int. Med Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Fang, G.-W.; Xue, Y. MicroRNA-375 as a potential serum biomarker for the diagnosis, prognosis, and chemosensitivity prediction of osteosarcoma. J. Int. Med Res. 2017, 46, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, G.; Murphy, M.L.; Huvos, A.G.; Gutierrez, M.; Marcove, R.C. Chemotherapy,en bloc resection, and prosthetic bone replacement in the treatment of osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer 1976, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Majeti, B.K.; Acevedo, L.M.; A Murphy, E.; Mukthavaram, R.; Scheppke, L.; Huang, M.; Shields, D.J.; Lindquist, J.N.; E Lapinski, P.; et al. MicroRNA-132–mediated loss of p120RasGAP activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, C.; Zhang, C.; Luo, C.; Zhong, B.; Yu, X. MiRNA-132 regulates the development of osteoarthritis in correlation with the modulation of PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, T.; Tang, J.; Cai, H.; Lin, L.; Fu, S. Loss of microRNA-132 predicts poor prognosis in patients with primary osteosarcoma. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 381, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Zhou, X. Identification of Serum MicroRNA-21 as a Biomarker for Chemosensitivity and Prognosis in Human Osteosarcoma. J. Int. Med Res. 2012, 40, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Feng, G. Digitalization and third-party logistics performance: Exploring the roles of customer collaboration and government. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2023, 53, 467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Gougelet, A.; Pissaloux, D.; Besse, A.; Perez, J.; Duc, A.; Dutour, A.; Blay, J.; Alberti, L. Micro-RNA profiles in osteosarcoma as a predictive tool for ifosfamide response. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 129, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gu, J.; Shen, H.; Shao, T.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z. Circular RNA LARP4 correlates with decreased Enneking stage, better histological response, and prolonged survival profiles, and it elevates chemosensitivity to cisplatin and doxorubicin via sponging microRNA-424 in osteosarcoma. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 34, e23045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessner, A.; Lohmann, C.; Jechorek, D. Translational cell biology of highly malignant osteosarcoma. Pathol. Int. 2021, 71, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Dean, D.; Hornicek, F.J.; Chen, Z.; Duan, Z. The role of extracelluar matrix in osteosarcoma progression and metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywa, T.M.; Klicka, K.; Włodarski, P.K. Regulators at Every Step—How microRNAs Drive Tumor Cell Invasiveness and Metastasis. Cancers 2020, 12, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Dang, H.X.; Lim, D.A.; Feng, F.Y.; Maher, C.A. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, N.; Alessio, N.; Di Paola, A.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Galderisi, U.; Russo, A.; Rossi, F.; Potenza, N. Osteosarcoma in a ceRNET perspective. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, S.; Behmanesh, A.; Mazhar, F.N.; Bagherifard, A.; Sami, S.H.; Heidari, N.; Hossein-Khannazer, N.; Namazifard, S.; Arki, M.K.; Shams, R.; et al. Machine learning and experimental analyses identified miRNA expression models associated with metastatic osteosarcoma. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behulová, R.L.; Bugalová, A.; Bugala, J.; Struhárňanská, E.; Šafranek, M.; Juráš, I. Circulating Exosomal miRNAs as a Promising Diagnostic Biomarker in Cancer. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, S193–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Min, L. The Roles of Exosomes in Metastasis of Sarcoma: From Biomarkers to Therapeutic Targets. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Wang, L.; Gao, G.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Miu, Y. Identification and verification of microRNA signature and key genes in the development of osteosarcoma with lung metastasis. Medicine 2022, 101, e32258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, F.S.; Schmidt, C.; Franke, F.; Jechorek, D. Roessner A Integrated Genomic and Epigenetic Analysis of Matched Primary and Metastatic Highly Malignant Osteosarcoma. 2025, in preparation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tumor Benign/ Malignant |

ncRNA | Material | Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enchondroma/Chondrosarcoma | miR-181a and -138 | Tumor tissue FFPE |

Increased expression of miR-181a and -138 in low grade chondrosarcoma compared with enchondroma | Zhang, L. et al. 2017 [108] |

| Benign Hyperplasia (BPH)/ Prostatic Cancer |

miR-27b-3p, miR-574-3p, miR-30a-5p, and miR-125b-5p | Urine | These miRNAs can discriminate between BPH and Prostatic Cancer | Stella et al. [109] |

| Benign Nodules/Thyroid Cancer | miRNA-222 | Serum | Discriminating between thyroid cancer and benign nodules. |

Bielak et al. [110] |

| High risk benign Breast Tumors/ Breast Cancer | miRNAs, hsa-mir-128-3p, hsa-mir-421, hsa-mir-130b-5p, and hsa-mir-28-5p, | Plasma | four miRNAs, hsa-mir-128-3p, hsa-mir-421,has-mir-130b-5p, and hsa-mir-28-5p, were differentially expressed in CA vs. HB and had diagnostic power to discriminate CA from HB | Khadka et al. [112] |

| Benign Breast Disease/ Breast Cancer | miR-106b-5p, −126-3p, −140-3p, −193a-5p, and −10b-5p | Plasma | multi-marker panel consisting of hsa- miR-106b-5p, −126-3p, −140-3p, −193a-5p, and −10b-5p could detect early-stages of BC with 0.79 sensitivity, 0.86 specificity and 0.82 accuracy. |

Sadeghi et al. [111] |

| Benign liver tumors/liver cancer | LincRNA- 01093 lncRNA HELIS |

Serum | LINC01093 and lncRNA HELIS are down-regulated in all malignant liver cancers; in benign tumors LINC01093 expression is just twice decreased in comparison to adjacent tissue samples. |

Burenina et al. [113] |

| Nonneoplastic skin diseases/different skin cancers | miRNA-Based Deep Cancer Classifier miR-375 and miR-451 |

Serum | miR-375 and miR-451 are candidate biomarkers of neoplastic and non neoplastic skin lesions | Kaczmarek et al. [96] |

| Benign and Malignant Effusions | miR-141-3p, miR-203a-3 | Pleural fluid | abundance of three miRNAs miR-141-3p, miR-203a-3, and miR-200c-3p correctly classi- fies malignant pleura effusions |

Marques et al. [114] |

| Malignant borderline tumors/ovarian cancer | miR-30a-3p, miR-30c, miR-30d and miR-30e-3p | Tumor tissue FFPE | Four miRNAs could discriminate mucinous borderline tumors and ovarian cancers |

Dolivet et al. [115] |

| Benign versus malignant adrenocortical tumors | miR-139-3p, miR-335, miR-675 | miRNA profiling of miR-675, and miR-335, and miRNA-139-3p helps in discriminating ACCs from ACAs Adreno-cortical adenomas and carcinomas | Schmitz et al. [116] |

| Tumor Benign/ Malignant |

ncRNA | Material | Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoblastoma/ Osteosarcoma |

miRNA-210 | Tumor tissue FFPE |

miRNA-210 displays low levels of expression across all of the osteoblastoma specimens and high expression in the majority of the osteosarcoma specimens. |

Riester et al. [124] |

| Fibrous dysplasia; giant cell tumor of the bone; osteoblastoma; chondrosarcoma; versus osteosarcoma |

miR-1261 | Serum | patients with osteosarcoma had higher serum miR-1261 levels than those with benign or intermediate-grade bone tumors |

Araki Y et al. 2023 [130] |

| Non coding RNA | Materials | Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1261 | Serum | Higher miRNA serum levels point to a bone tumor of high-grade malignancy. | Araki A et al. [130] |

| miR-337-3p, miR-484, miR-582, miR-3677 | Serum | These miRNAs were decreased in serum of osteosarcoma patients | Luo, H et al. [131] |

| MiR-429 and MiR-143-3p | Serum | MiR-429 and miR-143-3p expression were significantly down-regulated in the serum from OS patients. | Yang, L et al. [132] |

| circRNA hsa_circ_0003074 | Serum | hsa_circ_0003074 is highly expressed and peripheral blood of osteosarcoma patients. . |

Lei, S et al. [133] |

| miR-101 | Serum | miR-101 expression levels were under-expressed in serum samples from osteo-sarcoma patients compared to controls. | Yao, ZS et al. [134] |

| miR-124 | Serum | The level of serum miR-124 was decreased in osteosarcoma patients when compared to healthy controls. | Cong, C et al. [135] |

| miR-95-3p | Serum | Compared to healthy controls, the expression levels of miR-95-3p in serum of osteosarcoma patients was signifi-cantly decreased. |

Niu, J et al. [136] |

| miRNA-223 | Serum | The expression of miR-223 was significantly decreased in the serum of osteosarcoma patients compared to healthy controls. | Dong, J et al. [137] |

| miR-195-5p, miR-199a-3p, miR-320a and miR-374a-5p | Plasma | Were significantly increased in the osteosarcoma patients and markedly decreased in the plasma after operation. | Lian F et al. [138] |

| microRNA-221 | Serum; Fresh frozen tissue |

The expression levels of miR-221 in osteosar-coma tissues and sera were both upregulated. | Yang, Z et al. [139] |

| Non coding RNA | Materials | Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-34c-3p and miR-154-3p | Sarcoma tissue, FFPE | The combined values of miR-34c-3p and miR-154-3p showed 90 % diagnostic power for osteosarcoma samples and 85 % for metastatic osteosarcoma. | Abedi, S. et al. [183] |

| miR-675 miR-1307 miR-25-3p |

Serum and plasma | Osteosarcoma-derived exosomal biomarkers, including miRNAs, and lnc-RNAs, reveal diagnostic value and the potential of predicting prognosis for osteosarcoma metastasis. |

Tan, L. et al. [185] |

| miR-34a | Serum | Elevated serum levels of miR-34a were associated with a reduced incidence of metastasis in OS patients. |

Lian, H. et al. [167] |

| miR-506 | Sarcoma tissue, FFPE | microRNA-506 was differentially expressed between osteosarcoma tissues with lung metastasis and non-metastatic tumor tissue. | Meng, F. et al. [186] |

| miR-98-3p; miR-134-3p; miR-378C; miR-516A-5p; miR-548A-3p; miR-606; miR-650; miR-802; miR-1233-3p; miR-1271-3p; miR-3158-3p |

Sarcoma tissue, FFPE | The most differential expressed miRNAs (highly significantly) were observed between the non-metastasizing OS and the metastasizing primary OS | Karras, F. in preparation [187] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).