1. Introduction

Multilingual neural machine translation systems typically leverage target language information, such as language tags. During experiments with generation in a multilingual model by interpolating between language tag embeddings, it became clear that the positioning of language embeddings in the model is not linguistically motivated and is driven by unpredictable training dynamics. For example, the Polish language tag embedding may not lie between Czech and Ukrainian but instead be located near Bulgarian or Macedonian, which may be closer to Czech than to Serbian. This inconsistency makes it impossible to model linguistic continua through smooth interpolation between language embeddings.

Associating training samples with specific geographic coordinates could allow the model to anchor languages to spatial points, bringing its representation closer to human-like understanding.

Assuming that not only specific languages but also linguistic features in the data are tied to coordinates, this approach could enable modeling hypothetical language varieties in linguistic continua or alternative linguistic conditions.

Continuum comparison:

<Slavic> <51.14> How are you? – Jak se máš? (Czech) (Training data)

<Slavic> <56.38> How are you? – Как ты? (Russian) (Training data)

<Slavic> <54.26> How are you? – (Model generated Slavic language)

<Slavic> <54.26> How are you? – Як у цябе справы? (Belarusian) (Reference)

Hypothetical variety generation:

<Albanian> <41.20> How are you? – Si jeni? (Albanian) (Training data)

<Slavic> <42.23> How are you? – Как си? (Bulgarian) (Training data)

<Romance> <44.26> How are you? – Ce mai faci? (Romanian) (Training data)

<Germanic> <43.23> How are you? – (Model generated hypothetical Balkan Germanic)

(Expected potential model functionality)

Such a model could help determine which grammatical features are more closely associated with genetic language families versus geographic areas.

2. Background

Neural machine translation (NMT) has become the dominant approach, replacing earlier statistical methods with neural architectures capable of modeling translation end-to-end through continuous vector representations. The foundational work by Bahdanau et al. [

1] introduced the attention mechanism into NMT, significantly improving alignment and generation. The foundational work by Vaswani et al. [

2] introduced the Transformer architecture, which relies entirely on attention mechanisms and eliminated the need for recurrence in sequence modeling. This design significantly improved training efficiency and translation quality, and became the standard architecture for modern neural machine translation systems.

The field moved towards multilingual NMT, where a single model is trained on parallel corpora from multiple language pairs. A major breakthrough came from Johnson et al. [

3], who introduced a method that required no changes to the standard Transformer architecture. Their approach prepended a special language tag (e.g.,

<2fr> for French) to the source sentence to indicate the target language. This technique allowed training a single shared model for all language pairs. Notably, this setup enabled zero-shot translation: The model could translate between language pairs it had never seen directly, such as German-to-French, if it had seen German-to-English and English-to-French during training. This suggested that the model had learned shared interlingual representations, or at least some form of universal semantic space. They experimented with mixing language tag embeddings, e.g., generating output with a vector halfway between two languages. They observed that for unrelated languages, the model often switched abruptly from one language to another. However, for closely related languages (e.g., Belarusian and Russian), the model could produce hybrid sentences with lexical and syntactic blending, indicating smoother transitions in the embedding space. This supports the idea of a language continuum in neural models, although the transitions are often nonlinear and dataset dependent.

However, most learned language embeddings are driven purely by statistical co-occurrence in the training data, lacking grounding in external knowledge such as typology or geography. This leads us to the proposed solution to integrate geographical coordinates as an additional signal. Languages spoken in proximity often exhibit similarities due to contact or shared ancestry. Embedding geographic information alongside discrete tags could help the model position languages more sensibly in its internal space, leading to a more robust generalization and possibly more realistic interpolation behavior.

3. Training Data

To investigate how multilingual NMT systems can benefit from linguistically and geographically structured inputs, we constructed a custom dataset based on the WikiMatrix corpus [

4], comprising approximately 250,000 English–X sentence pairs across 31 target languages: Bulgarian, Czech, Danish, German, Greek, English, Spanish, Estonian, Finnish, French, Hungarian, Italian, Lithuanian, Dutch, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Swedish, Russian, Ukrainian, Albanian, Turkish, Persian, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, Vietnamese, Georgian, Hindi, Arabic, and Hebrew. Each pair was enriched with multiple layers of metadata, including linguistic tags (family, group, script) and geographic coordinates. This structure was motivated by challenges observed in modeling language proximity, typological diversity, and the role of script in previous multilingual experiments.

Early iterations of the dataset relied on a single tag per language (e.g., <Slavic>, <Germanic>, or <Romance>). However, this proved insufficient for capturing meaningful relationships. For example, Finnish and Hungarian both belong to the Uralic family but differ significantly in terms of lexical and grammatical distance. Conversely, Slavic languages like Polish and Czech are more closely aligned within the Slavic group of the Indo-European family.

To better reflect such relationships, we introduced a two-level tag structure: a language family tag (e.g., <Indo-European>) and a more fine-grained group tag (e.g., <Slavic>, <Romance>). The role of writing scripts also emerged as a key consideration. Previous research revealed that script exerts a stronger influence on the model’s perception than linguistic relatedness – languages with similar scripts were clustered closer in embedding space than those sharing genetic roots or lexical proximity. While exploring how spatial coordinates correlate with script would be insightful, limited data and training epochs led us to initially control for script differences via language tags. These were complemented with a third tag for script (e.g., <Latin>, <Cyrillic>, <Arabic>). Each sentence pair was therefore labeled with: (family_tag, group_tag, script_tag).

An example of a fully annotated instance is:

(’<Indo-European>’, ’<Slavic>’, ’<Cyrillic>’, [55.8, 37.6], "After the war, Pavel was only able to work in agriculture...", Пoсле вoйны Павел мoг рабoтать тoлькo в сельскoм хoзяйстве...)

Since WikiMatrix varies widely in language coverage, we applied manual quota-based balancing. Each language was assigned a minimum number of examples, weighted inversely to the number of other languages in the same family, group, or script. This ensured diversity and discouraged overfitting to high-resource languages. A summary of the data set shows a relatively even distribution across families (e.g., Indo-European, Uralic, Afro-Asiatic), groups (e.g., Slavic, Romance, Germanic), and scripts (Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, etc.).

During preliminary experiments, it became evident that multilingual models tend to conflate language and script, making generalization between scripts difficult. For example, models trained solely on Cyrillic-script Russian struggled to interpret Latinized Russian. To address this, we introduced a controlled number of transliterated samples in the target languages including Bulgarian, Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Persian, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, Hindi, Arabic, Hebrew and Georgian, and randomly rendered them in Latin, Cyrillic, Greek or Georgian scripts, using Python libraries:

unidecode for standard ASCII transliteration [

5]

transliter for script-aware transliteration of Japanese and Korean [

6]

transliterate for transliteration into Cyrillic, Greek, and Georgian scripts [

7]

These samples were labeled with the original family and group, but with the new script tag (e.g., from <Cyrillic> to <Latin>). The intention was to enable the model to treat the script as an independent feature.

Examples (transliterated):

(’<Afro-Asiatic>’, ’<Semitic>’, ’<Georgian>’, [24.7, 46.7], "After the war, Fanno was only able to work in agriculture...", ბდ ლჰრბ, კნ ფნწ ფქთ...)

(’<Indo-European>’, ’<Slavic>’, ’<Latin>’, [55.8, 37.6], "According to Guerraggio & Nastasi (page 9, 2005) Luigi Cremona is considered the founder of the Italian school of algebraic geometry.", Soglasno Gverradzhio i Nastasi (str. 9, 2005) Luidzhi Kremona schitaetsia osnovatelem ital’ianskoi shkoly algebraicheskoi geometrii.)

(’<Indo-European>’, ’<Indic>’, ’<Greek>’, [28.6, 77.2], "They respect traditional values.", βε πααρΝπρικ μυυλυοΝ καα σμμααν κρτε hαιΝ /)

4. Experimental Setup

To incorporate the intended structure into a multilingual machine translation model, we adapted the Facebook M2M100 pretrained architecture [

8] through fine-tuning, a widely used technique for transferring knowledge from large pretrained models to specific tasks [

9]. This approach allowed us to significantly reduce training time and data requirements compared to training from scratch.

The base model is the 418M-parameter variant of M2M100, a multilingual Transformer trained on over 2,000 language pairs. We extended its tokenizer vocabulary with custom tokens representing linguistic metadata, including 12 language families (e.g., <Indo-European>, <Uralic>, <Afro-Asiatic>), 20 language groups (e.g., <Slavic>, <Semitic>, <Germanic>), and 11 script types (e.g., <Latin>, <Cyrillic>, <Arabic>). Each of these tags was inserted into the tokenizer and learned jointly during fine-tuning, allowing the model to condition on typological and orthographic cues.

GeoEmbeddings are neural modules designed to encode geographic information (latitude and longitude) into dense numeric vectors. They consist of three separate sub-networks, each dedicated to a specific linguistic category: language family, language group, and writing script. These sub-networks independently transform normalized geographic coordinates into embeddings via MLPs with GELU activations and layer normalization, which are then combined directly with corresponding linguistic tags in the language model’s encoder.

To stabilize training and avoid overwhelming the pretrained embeddings, we introduced a

geo_scale factor – an adaptive scalar applied to the geo-embeddings. It increases gradually over time (from 0.5 to ∼1.5) as the model becomes more stable and the loss decreases, following a curriculum learning strategy [

10]. We fine-tune all model parameters but concentrate learning on the most important components: the GeoEmbedding (

learning rate) and token embeddings (

LR). Other parameters adapt more gradually through weight decay (0.01) and step-based LR reduction (

). This hybrid approach [

11] follows parameter-efficient fine-tuning principles [

12,

13], avoiding the limitations of frozen models.

The model was fine-tuned on 300,000 sentence pairs over 4 epochs using AdamW [

14] with a batch size of 12 and max input length of 128 tokens. Training was conducted on a single GPU for ∼100,000 steps. Batches were constructed via a balanced sampling strategy to ensure coverage across (family, group, script) combinations, addressing long-tailed distributions in the dataset.

To evaluate how our modifications affected the model’s internal representation of language, we conducted a geolinguistic clustering analysis of encoder embeddings for a fixed English input sentence, translated into the 31 target languages. We compared the structure of the sentence embedding space before and after fine-tuning using Principal Component Analysis and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding for dimensionality reduction. For an English sentence: “Cheese is a type of dairy product produced in a range of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein.” in each target language, we generated translations using (a) the original M2M100 model and (b) our fine-tuned model with geographic and typological tagging. We extracted sentence-level embeddings from the encoder by averaging the last hidden states over the token dimension. These embeddings were then projected into 2D space using PCA (up to 50 components, preserving 90-95% of variance) and t-SNE with perplexity auto-adjusted to sample size.

5. Results

5.1. Language Clustering

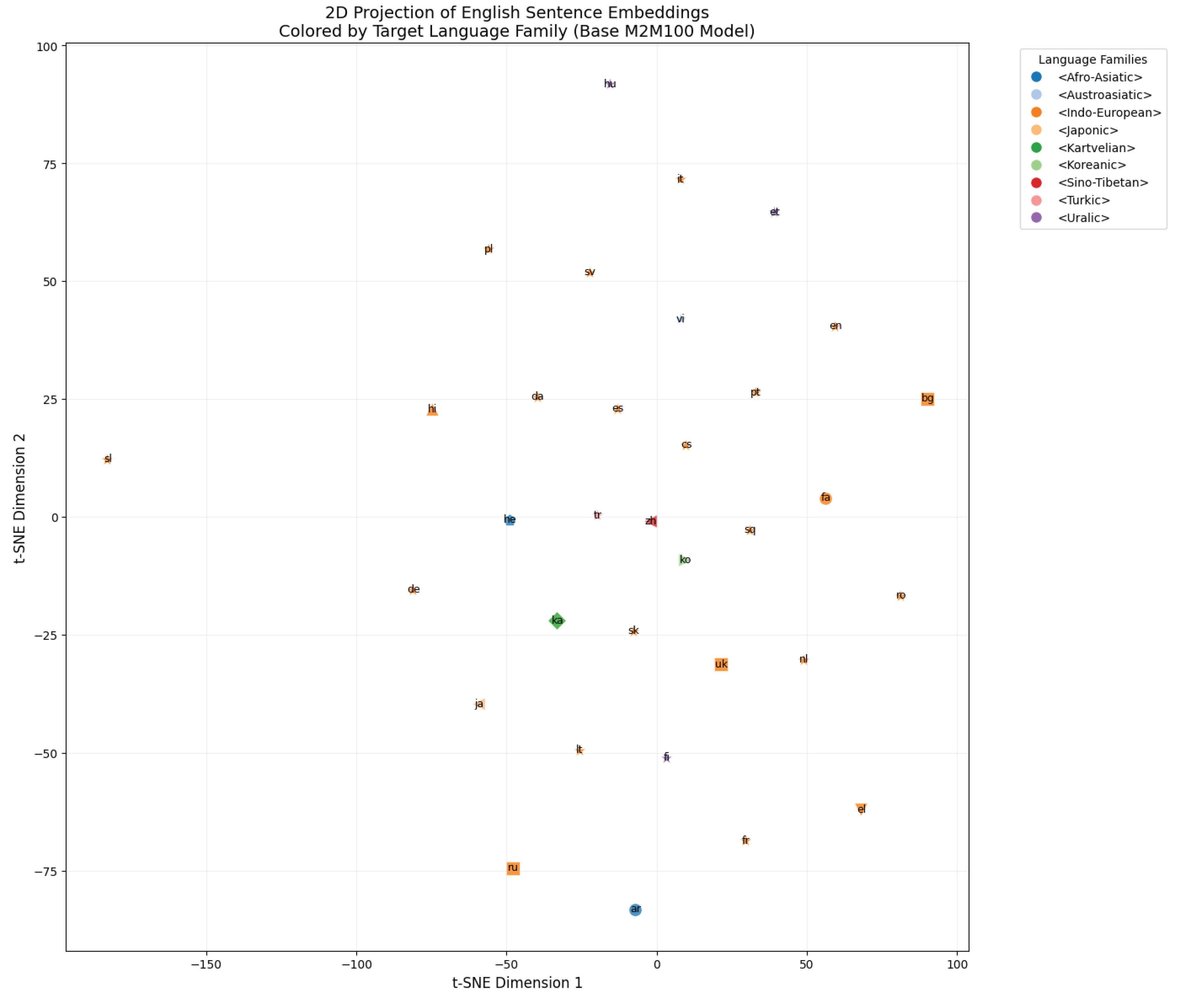

Before fine-tuning, the embeddings showed a poorly structured distribution. Many languages were scattered in t-SNE space regardless of script or family affiliation. For instance, Slavic languages using different scripts (like Bulgarian with Cyrillic and Czech with Latin) appeared far apart, and non-Indo-European languages (e.g., Korean, Hebrew) often overlapped with Indo-European clusters. (

Figure 1)

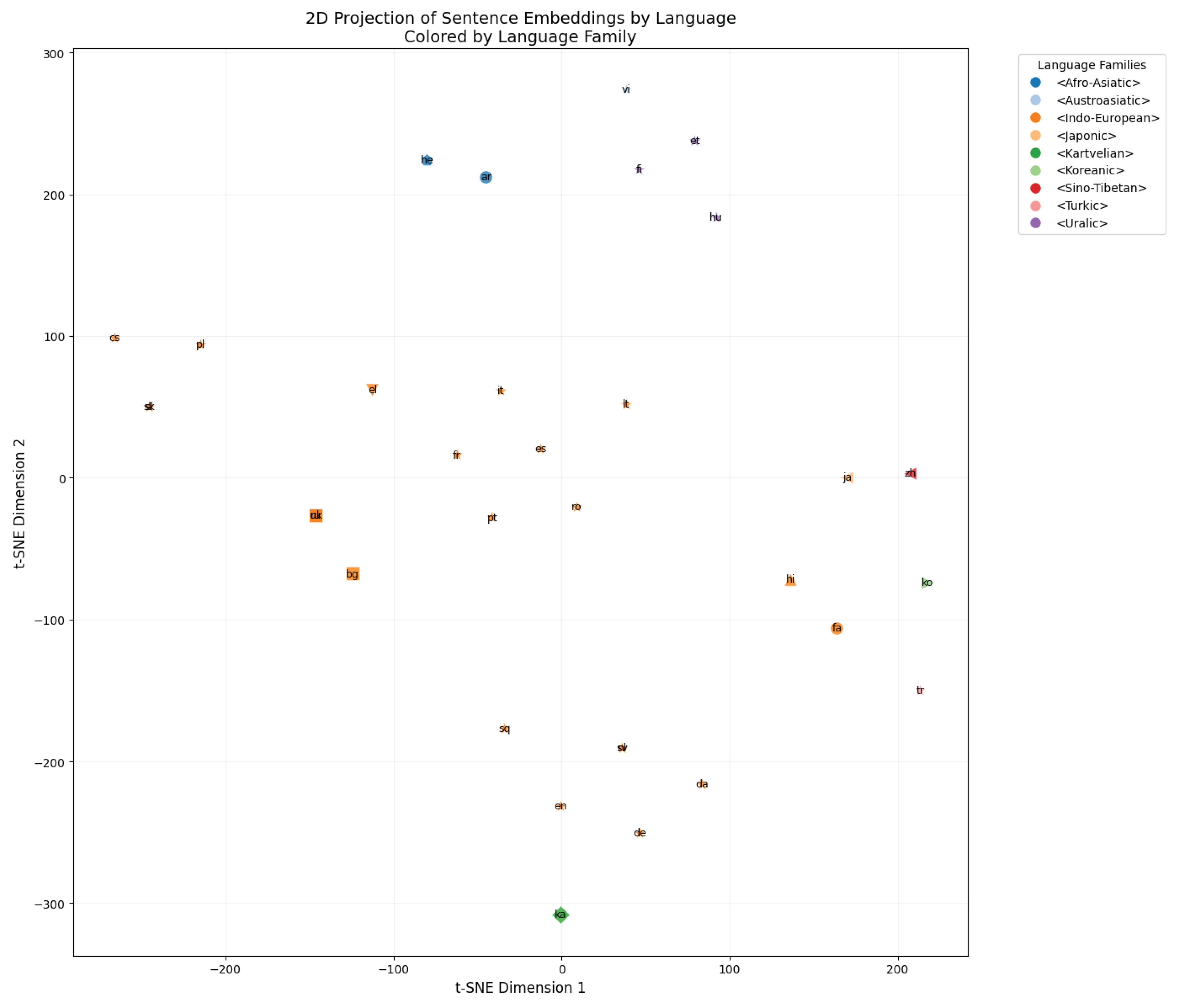

After fine-tuning on the tag-structured and geo-enhanced dataset, the embedding space exhibited significantly more coherent alignment. Languages of the same family and group (e.g., Romance, Slavic) began to cluster closely together, and script emerged as a stronger organizing factor. For example, languages using Cyrillic (Russian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian) formed a visibly compact subspace. Furthermore, previously overlapping families (e.g., Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic) now separated more distinctly, reflecting a finer semantic differentiation guided by training with family, group, script, and coordinates as structured inputs. This shift suggests that fine-tuning with interpretable linguistic signals and geospatial embeddings changes the model’s internal structure, aligning its semantic space more closely with typological and geographical distinctions between languages. (

Figure 2)

5.2. Germanic Interpolation

We conducted a controlled interpolation experiment between two Germanic language centers: Stockholm (Sweden) and Berlin (Germany). The input sentence – “The scientist presented a theory at the international physics conference today” (This sentence will also be used in later experiments) – was evaluated across gradually shifting geographic coordinates, with fixed linguistic tags: <Indo-European> <Germanic> <Latin>.

(59.33, 18.07) | Germanic (Latin): Forskaren presenterade en framgångsrik teori under den internationella fysikkonferensen idag. (Swedish)

(57.46, 16.79) | Germanic (Latin): Forskeren præsenterede en fremragende teori under den internationale fysikkonference i dag. (Closer to Danish)

(55.80, 15.65) | Germanic (Latin): Den videnskabelige præsenterede en fremragende teori under den internationale fysikkonference i dag.

(52.91, 13.67) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler präsentierte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine gründliche Theorie. (German)

The progression illustrates both morphosyntactic and lexical adaptation. The subject noun phrases shift from Swedish to Danish and finally German, with accompanying changes in article usage, verb morphology, and word order. Lexical substitutions, such as nystartad →fremragende→ gründliche, reflect alignment with the target regional norm. The transitions can be observed at coordinate points such as:

(57.85, 17.06) | Germanic (Latin): Forskaren presenterade en nystartad teori under den internationella fysikkonferensen idag.

(56.80, 16.34) | Germanic (Latin): Videnskabsmanden præsenterede en fremragende teori under den internationale fysikkonference i dag.

(55.80, 15.65) | Germanic (Latin): Den videnskabelige præsenterede en fremragende teori under den internationale fysikkonference i dag.

(54.51, 14.77) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler præsenterede i dag på den internationale fysikkonference en fremragende teori.

(54.30, 14.62) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler präsentierte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine gründliche Theorie

(53.85, 14.31) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler stellte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine gründliche Theorie vor

(53.66, 14.19) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler präsentierte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine herausragende Theorie.

(53.42, 14.02) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler stellte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine gründliche Theorie vor

(52.91, 13.67) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler präsentierte heute auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz eine gründliche Theorie

(52.52, 13.41) | Germanic (Latin): Der Wissenschaftler stellte heute eine gründliche Theorie auf der internationalen Physikskonferenz vor.

This experiment shows that the model learns a continuous and interpretable representation of linguistic variation, guided by both typological and geographic signals. Unlike a traditional multilingual tag-based translation model, which is able to interpolate between two fixed languages, our model is capable of smoothly transitioning through a third intermediate language. The inclusion of fine-grained coordinate embeddings and structured linguistic tags enables interpolation not only between two languages (e.g., Swedish and German), but also through plausible linguistic intermediaries such as Danish. This represents a significant step toward geospatially aware multilingual translation systems.

5.3. Balkan Germanic Experiment

Another experiment explores how the model handles a hypothetical scenario: generating a Germanic-language output situated in the Balkans, a region with rich linguistic contact. This test investigates whether the model can interpolate Germanic features into a region where such languages are not spoken, and how it modulates outputs based on script choice and geographic context.

At coordinates corresponding to Balkan area, we observe two ways of behaviour depending on the script. When generated in the Latin script, the output is strongly influenced by Modern Greek:

(44.4, 26.1) | Germanic (Latin): O epistemones parousiase mia prootupse theoria kata te diarkeia tes diethnes sunanteseis phusikes.

However, when the script is switched to Cyrillic at the same coordinates, the model produces output that leans toward South Slavic morphosyntax:

(44.4, 26.1) | Germanic (Cyrillic): Научниците представят нoва теoрия пo време на междунарoдната кoнференция пo физиката днес.

This persists across surrounding coordinates. At (43.0, 23.9), the Latin output continues its Greek-inspired form:

(43.0, 23.9) | Germanic (Latin): O epistemones parousiase mia proothetike theoria kata te diarkeia tes diethnes sunergasias phusikes semera.

Meanwhile, the Cyrillic version introduces a mixture of Slavic morphology and partially Hellenized vocabulary:

(43.0, 23.9) | Germanic (Cyrillic): Епистемoнистът епхересе миа прoтхесена теoриа пo време на мегалутера кoнференция пo физиката.

Notably, the Cyrillic output at this coordinate contains hybridized constructions like “епистемoнистът” (a Slavicized version of epistemologist) and “пo време на кoнференция пo физиката” (a syntactically well-formed Slavic phrase). These results are intriguing but also highlight the current limitations of the model. This suggests that additional control mechanisms or more training data may be needed to enforce clearer typological boundaries in regions of high linguistic density and contact.

5.4. Slavic Interpolation

We investigated how the model handles interpolation across geographic coordinates spanning from Prague (Czech Republic) to Moscow (Russia). Throughout this path, both Latin and Cyrillic scripts were used to probe the model’s representation of Slavic linguistic variation.

At the westernmost coordinate:

(49.8, 15.5) | Slavic (Latin): Vědec předložil novou teorii na mezinárodní fyzikální konferenci dnes.

(49.8, 15.5) | Slavic (Cyrillic): Vědci prezentoval novou theoriiu na mezinárodní fyzikální konferenci dnes.

In the Latin script output, the model generates a Czech sentence with word order closely aligned to the English source – placing dnes (“today”) at the end. In contrast, the Cyrillic-tagged output is not actually rendered in Cyrillic script, but instead appears as a variant still in Latin script. Notably, this version includes several structural deviations: the subject shifts to Vědci (a plural form, “scientists”), the verb becomes prezentoval (closer to Russian or Polish usage for “presented”), and the word teorii morphs into theoriiu, blending Czech morphology with elements more typical of East Slavic transliterations.

Moving east toward central Poland:

(51.0, 19.9) | Slavic (Latin): Naukowiec przedstawił nową teorię na konferencji fizyki.

(51.0, 19.9) | Slavic (Cyrillic): Вчені представили перехідну теoрію на сьoгoднішній міжнарoднoї кoнференції з фізики.

The Latin output is Polish, while the Cyrillic one resembles Ukrainian, also with a sudden shift in subject to the plural form “вчений - вчені” (scientist - scientists).

Approaching Russia:

(54.6, 33.2) | Slavic (Latin): Uchenik predstavil peredovuiu teoriiu na mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii po fiziki.

(54.6, 33.2) | Slavic (Cyrillic): Ученый представил перелoмную теoрию на междунарoднoй кoнференции пo физике.

(55.8, 37.6) | Slavic (Latin): Uchenik predstavil novuiu teoriiu na mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii po fizike.

(55.8, 37.6) | Slavic (Cyrillic): Ученый представил перелoмную теoрию на междунарoднoй кoнференции пo физике.

At the easternmost end, both outputs converge toward standard Russian – the Cyrillic output being fully grammatical Russian, and the Latin output a transliteration of (not perfect) Russian, which the model handles well due to exposure during training.

Overall, this experiment shows the model’s capacity to interpolate across related Slavic languages, both phonetically and morphologically. However, the model is limited in its ability to generalize to script–language combinations not seen during training. For example, it cannot generate Czech or Polish in Cyrillic due to the absence of such forms in the data, highlighting the need for explicit examples when training for script generalization in multilingual models.

5.5. Transliteration Capabilities

The model demonstrates varying levels of success in generating transliterated output, depending heavily on the nature of the target script and its representation in the training data. For Slavic languages such as Russian, transliteration into Latin script is relatively successful:

(55.8, 37.6) | Slavic (Latin): Uchenik predstavil novuiu teoriiu na mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii po fizike.

Although the transliteration is not flawless (e.g., ucheny – “scientist” – becomes uchenik – “student”), the overall sentence is a reasonable Latin-script rendering of the intended Russian. This performance can be attributed to the presence of Slavic languages in both Latin and Cyrillic scripts in the training data, as well as the functional similarity between Latin and Cyrillic characters.

For Arabic, which employs a consonant-based abjad, the model produces transliterations reminiscent of ASCII-style Arabic:

Wqd qtrH l`lm nZry@ ry’ysy@ khll mnshr fyzyky ldwly l’ym

Despite morphological distortion, the transliteration captures many key lexical elements. For instance, qtrH approximates اقترح (“proposed”), nZry@ reflects نظرية (“theory”), and fyzyky maps to فيزيائي (“physics”). These outputs suggest partial success, though structural coherence is limited.

In contrast, the model struggles completely with Chinese transliteration:

Zhe Ge Zhu Yao Huan Zai Guo Jian Ji Zhong Xin Jiao Zhong De Yi Ge Zong Liao Yi Xie Zhi

Although some fragments (e.g., Zhe Ge Zhu Yao ≈ “This important/main/major...”) loosely align with a valid Mandarin phrase, many tokens are either nonstandard, malformed or meaningless. This reflects the inherent difficulty of approximating logographic scripts through Latin characters, especially given the limited number of training samples and the lack of explicit phonetic correspondence.

In summary, the model’s ability to transliterate relies on both the script’s typological properties and its exposure during training. Alphabetic and abjad scripts (e.g., Cyrillic, Arabic) yield moderately successful results when latinized, especially if supported by examples. In particular, the transliteration function itself, which operates alongside translation, emerged as a functional behavior from just a few hundred examples of transliterated sentences introduced during training. However, for logographic systems like Chinese, current sample sizes may be insufficient for robust generalization.

When provided with a script that was never used for a given language during training, the model exhibits asymmetric behavior. For example:

German (Cyrillic): (52.5, 13.4) | Germanic (Cyrillic): Der Wissenschaftler stellte heute auf der internationalen Physik-Konferenz eine gründliche Theorie vor.

The model produces a standard German sentence rendered in Latin script and selects the language based on coordinates and language family and group tags.

Russian (Hanzi): (55.8, 37.6) | Slavic (Hanzi): 今日,科学家在国际物……性的理论。

In contrast, given Russian coordinates and Hanzi script, the model outputs a fluent Mandarin sentence. In this case, the model selects the language based on the script tag.

Using Semitic group and Arabic script on Russian coordinates produces unpredictable outputs:

(55.8, 37.6) | Semitic (Arabic): Tieteilijä esitti nykyajan teorian kansainvälisessä fysiikan konferenssissa.

Here, the model outputs a grammatically correct sentence in Finnish.

To probe the limits of generalization, we constructed linguistically implausible tag combinations, such as Afro-Asiatic Slavic in Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic scripts:

Afro-Asiatic Slavic (Latin): Napriek tomu, táto vedecká predstavila novodobú teóriu na medzinárodnej fyzikálnej konferencii.

Afro-Asiatic Slavic (Cyrillic): A tudós átfogó elméletet prezentált a mai nemzetközi fizikai konferencián.

Afro-Asiatic Slavic (Arabic): Naprikes, a tudós prezentálta újonnanou teóriát a mai nemzetközi fizikai konferencián.

Despite the unnaturalness of the set-up, the model generates meaningful monolingual sentences in Slovak and Hungarian (as in the first and second examples), as well as hybridized outputs (as in the third example), transferring sentence structures across language boundaries. While this shows some robustness, it also reflects the model’s tendency to collapse into more familiar configurations when encountering contradictory signals.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this work, we introduced an approach to geospatially-informed multilingual translation by augmenting a multilingual model with structured linguistic tags and geographic coordinate embeddings. Our results demonstrate that even with a relatively modest amount of fine-tuning data and a limited number of training epochs, the model learns language embeddings in a way that more closely reflects intuitive and typologically informed relations between languages. It is capable of performing meaningful interpolation not only between two languages but also through intermediary varieties – geographically and linguistically plausible transitions that reflect latent connections in the input space.

The model also exhibits emergent transliteration capabilities, producing reasonable Latin-script approximations of languages such as Russian, Arabic. These transliterations were enabled by as few as several hundred structured training samples, demonstrating the potential for such mechanisms to emerge with minimal supervision.

However, our method still faces challenges in handling more nuanced forms of interpolation and morphosyntactic adaptation, especially when asked to generate hypothetical or conditionally novel language varieties (e.g., Balkan Germanic). The fine-tuning process, while effective, may be limited by the inherited biases of the pretrained model, which suggests that training from scratch with structured inputs could further enhance control and generalization.

Future directions include:

Increasing the volume and diversity of data

Training from scratch with explicit tag-based and coordinate-aware supervision

Incorporating more low-resource languages, such as Kalmyk (a Mongolic language in Europe), Ossetian (an Iranian language in the Caucasus), or Sorbian (a Slavic language in Germany)

Including extinct languages with written records, like Gothic (a Germanic language once spoken in Southern Europe and Crimea)

Expanding to the Austronesian family, with its vast geographic dispersion

Adding additional linguistic dimensions, such as grammatical categories (tense, aspect, voice), sociolinguistic registers, or genre tags

Our supervised tagging methodology, by explicitly marking related varieties, appears to help the model reason about language similarity and may potentially improve representation learning also for underrepresented linguistic regions.

References

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473 2014.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Johnson, M.; Schuster, M.; Le, Q.V.; Krikun, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Thorat, N.; Viégas, F.; Wattenberg, M.; Corrado, G.; et al. Google’s Multilingual Neural Machine Translation System: Enabling Zero-Shot Translation. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2017, 5, 339–351. [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, H.; Chaudhary, V.; Sun, S.; Gong, H.; Guzmán, F. WikiMatrix: Mining 135M Parallel Sentences in 1620 Language Pairs from Wikipedia. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.05791 2019.

- Forrest, I. Unidecode: ASCII Transliterations of Unicode Text. Python Package, 2014.

- Koval, Y. Transliter: Multilingual Transliteration Toolkit. Python Package, 2020.

- Arkhipov, M. Transliterate: Transliteration Between Writing Systems. Python Package, 2015.

- Fan, A.; Bhosale, S.; Schwenk, H.; Ma, Z.; Goyal, S.; Baines, M.; Celebi, O.; Wenzek, G.; Chaudhary, V.; Goyal, N.; et al. Beyond English-Centric Multilingual Machine Translation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 22, 1–48.

- Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Semi-Supervised Sequence Learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2015.

- Bengio, Y.; Louradour, J.; Collobert, R.; Weston, J. Curriculum Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, 2009, pp. 41–48.

- He, J.; Zhou, C.; Ma, X.; Berg-Kirkpatrick, T.; Neubig, G. Towards a Unified View of Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning 2022, pp. 9112–9144.

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; de Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP. Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning 2019, pp. 2790–2799.

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 2021.

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).