Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Biosynthesized AgNPs from Pseudomonas N5.12 on Cytoskeletal Structures in Arabidopsis Roots

2.2. Biological Effects of AgNPs on Tomato Plants

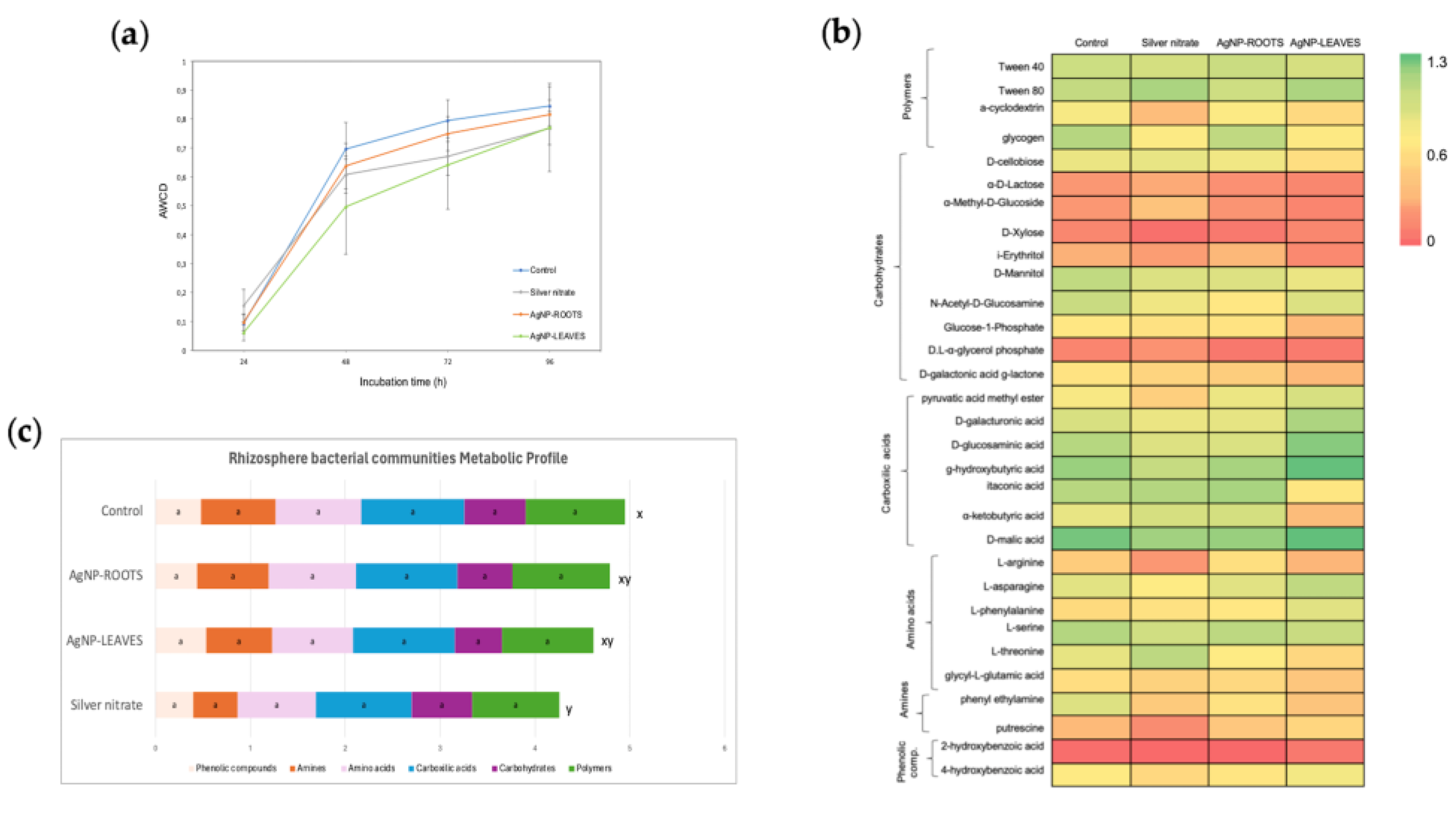

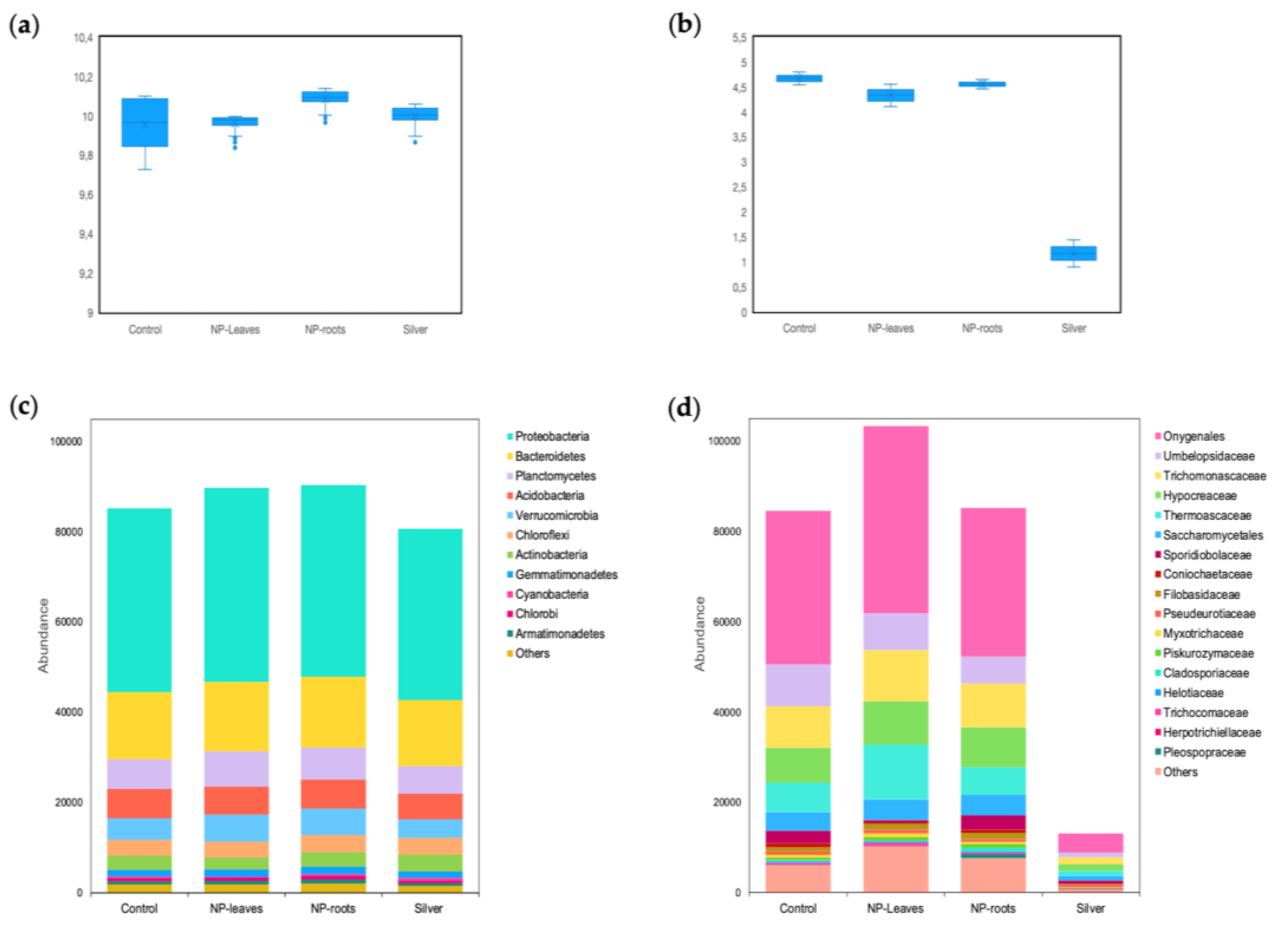

3.3. Microbial Community Diversity and Composition

3. Discussion

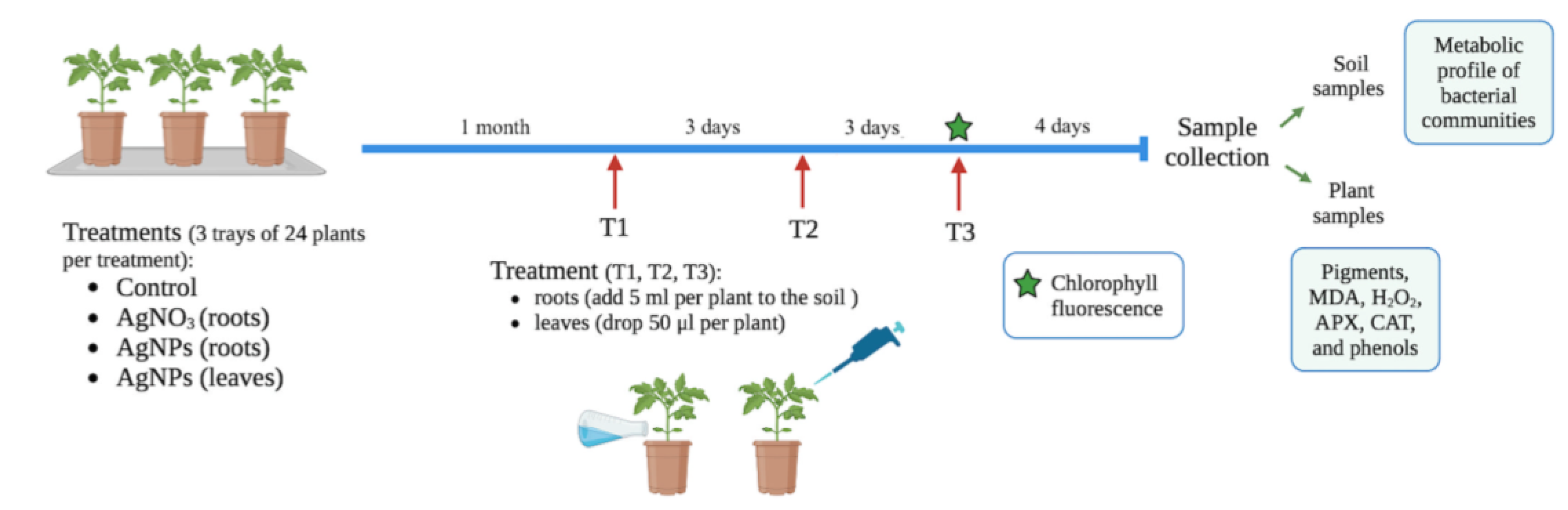

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biosynthesis of AgNP from Pseudomonas N5.12

4.2. Determination of Physiological Dose in Transgenic Arabidopsis

4.3. Experimental Design: Effect of AgNPs on Tomato Plants and Microbial Communities

4.4. Effects on Plant Physiology

4.4.1. Chlorophyll Fluorescence

4.4.2. Photosynthetic Pigments

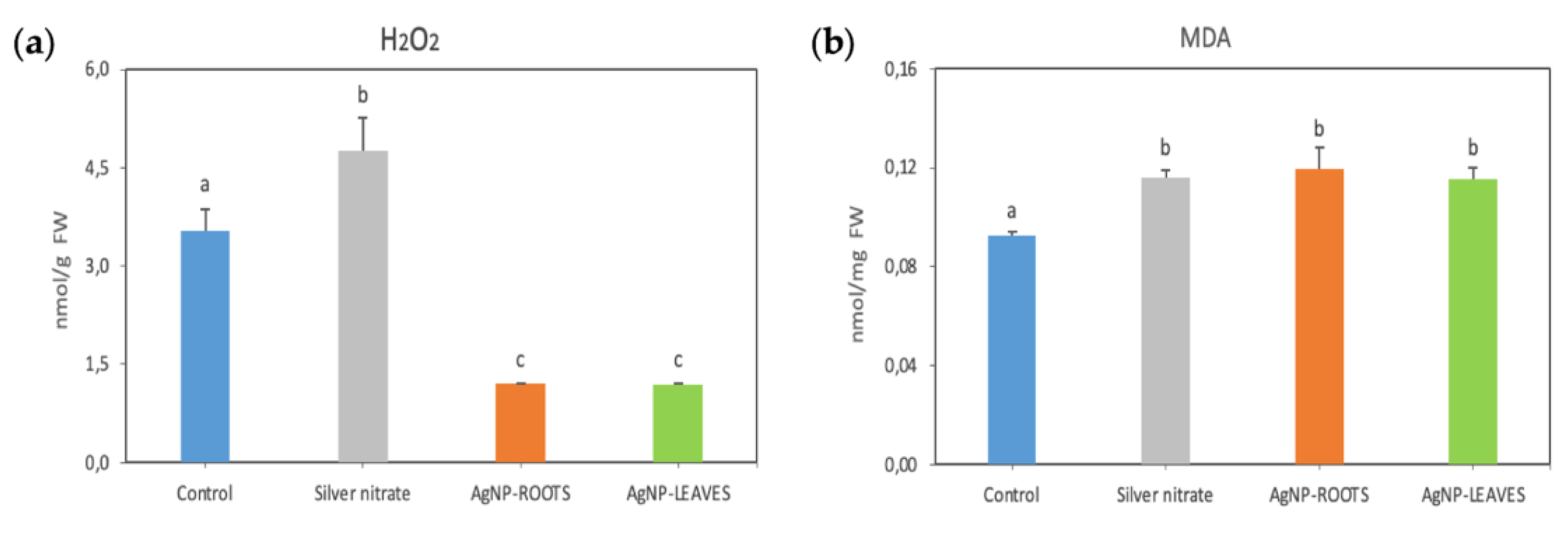

4.4.3. Oxidative Stress Markers

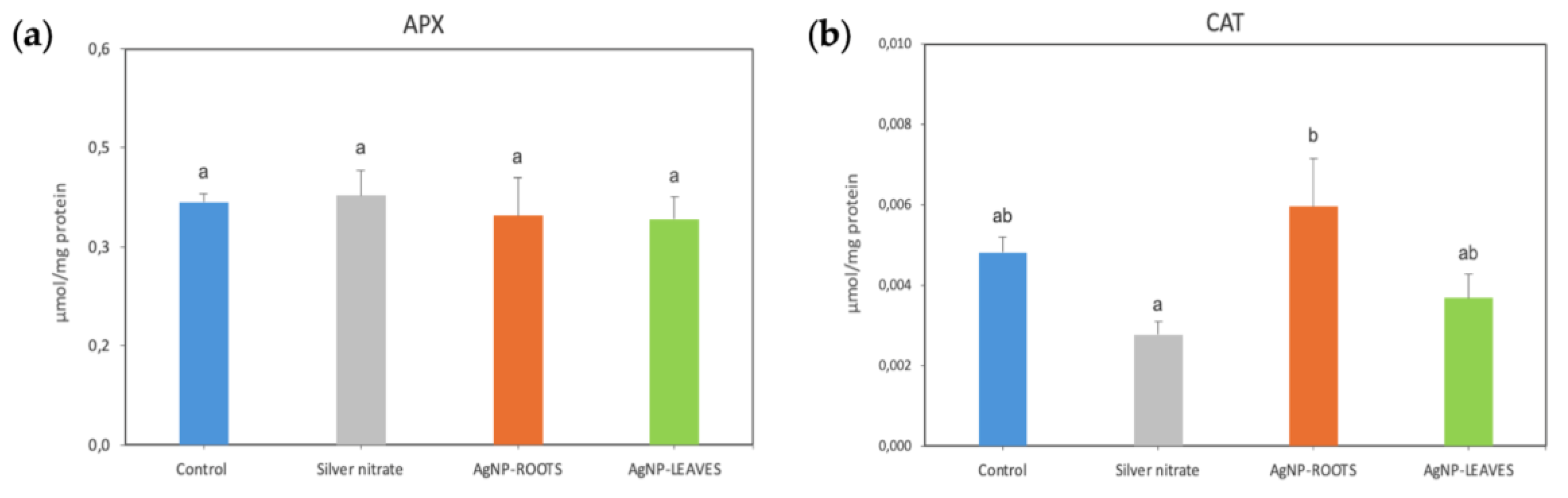

4.4.4. Enzyme Activities

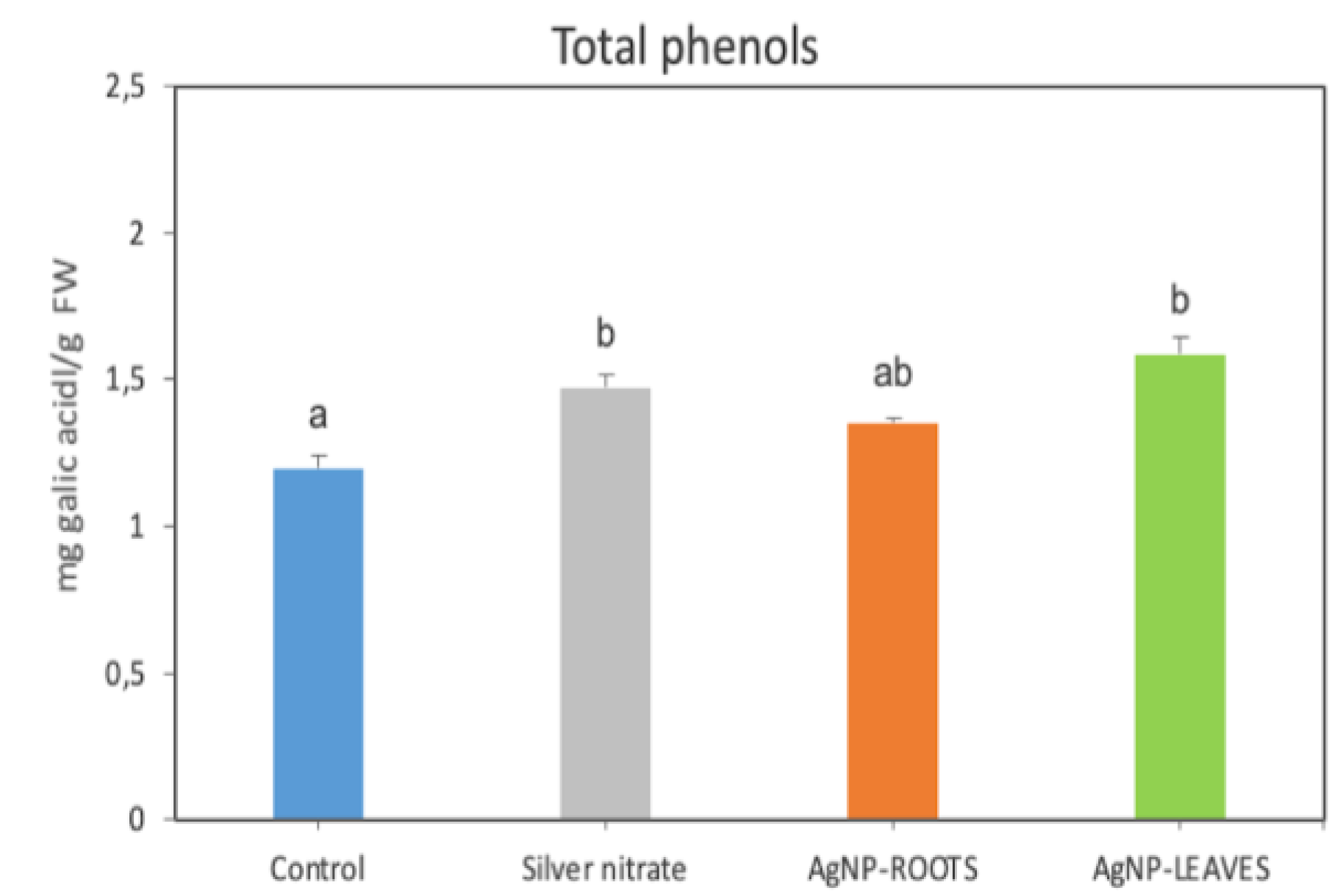

4.4.5. Total Phenols

4.5. Effects on Microbial Communities

4.5.1. Metabolic Profile of Soil Microbiota

4.5.2. Metagenomic Analyses of the Rhizosphere Bacterial and Fungi Communities

4.6. Statistics

5. Conclusions

- The metabolites from Pseudomonas N5.12 formulated in AgNPs have biological activity that is dose dependent, as shown by cytoskeleton alterations.

- Physiologically active doses are low and can be extrapolated to different plant species. AgNP coated with N5.12 metabolites (N5.12-AgNP) can effectively enhance tomato metabolism, highlighting the potential of nanotechnology-based solutions to promote sustainable agriculture.

- N5.12-AgNPs enhance plant resilience on tomato plants. Despite the increase in photosynthetic pigment contents and in MDA, H2O2 levels decreased, suggesting that coated AgNPs contribute to oxidative stress homeostasis in plant cells, modulating antioxidant molecules for ROS scavenging without involving major changes in specific antioxidant enzymes.

- N5.12-AgNPs did not significantly affect overall microbial diversity or activity, anticipating environmental safety. Furthermore, NP treatments favored beneficial bacteria groups like Proteobacteria.

- N5.12-AgNP can be delivered to the roots or to the leaves achieving similar effects either directly or systemically. Further studies are necessary to unveil differences.

- When formulated in AgNP, N5.12 metabolites are able to reduce silver, stabilizing the NP and preventing negative effects that could arise from oxidation of silver after delivery; negative effects have been evidenced on AgNO3 treatments at all levels.

- N5.12-AgNPs enhance plant fitness while maintaining rhizosphere microbial balance.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNP | Silver nanoparticles |

| MT | Microtubules |

| AF | Actin Filaments |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| AWCD | Average Well Color Development |

References

- Dhaka, A.; Chand Mali, S.; Sharma, S.; Trivedi, R. A review on biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their potential applications. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Synthesis, applications, toxicity and toxicity mechanisms of silver nanoparticles: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 253, 114636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mgadi, K.; Ndaba, B.; Roopnarain, A.; Rama, H.; Adeleke, R. Nanoparticle applications in agriculture: overview and response of plant-associated microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1354440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Chen, Z. Impacts of silver nanoparticles on plants: A focus on the phytotoxicity and underlying mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zahoor, M.; Sher Khan, R.; Ikram, M.; Islam, N. U. The impact of silver nanoparticles on the growth of plants: The agriculture applications. Heliyon 2023, 9, 16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, Z.; Alharbi, A. Effect of silver nanoparticles on seed germination of crop plants. J. Adv. Agric. 2015, 4, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Sarraf, M.; Afzal, S.; Das, S.; Rastogi, A. Silver nanoparticles in plant health: Physiological response to phytotoxicity and oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 209, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Báez, G. A.; Trejo-Téllez, L. I.; Ramírez-Olvera, S. M.; Salinas-Ruíz, J.; Bello-Bello, J. J.; Alcántar-González, G.; Hidalgo-Contreras, J. V.; Gómez-Merino, F. C. Silver nanoparticles increase nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium concentrations in leaves and stimulate root length and number of roots in tomato seedlings in a hormetic manner. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis. Soc. 2021, 19, 15593258211044576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Raja, N. I.; Mashwani, Z-U. R.; Hussain, M.; Ejaz, M.; Yasmeen, F. Effect of silver nanoparticles on growth of wheat under heat stress. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Sci. 2019, 43, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M. S. Impact of silver nanoparticles on plant growth, some biochemical aspects, and yield of fenugreek plant (Trigonella foenum-graecum). Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Shweta, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Upadhyay, N.; Singh, J.; Liu, S.; Singh, V. P.; Prasad, S. M.; Chauhan, D. K.; Tripathi, D. K.; Sharma, S. Differential phytotoxic impact of plant mediated silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and silver nitrate (AgNO3) on Brassica sp. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, G.; Liu, R.; Xu, A.; Chen, S.; Wu, L. Effects of ionic strength on physicochemical properties and toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Chauhan, N. S. Effect on nanoparticles on plant cell morphology, physiology, and metabolism. In The Impact of Nanoparticles on Agriculture and Soil; Chauhan, N. S., Gill, S. S., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, J.; Klassen, R.; Široká, J.; Novák, O.; Záruba, K.; Siegel, J.; Novotná, Z.; Valentová, O. Silver nanoparticles alter microtubule arrangement, dynamics and stress phytohormone levels. Plants 2022, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Chi, Q. Multifaceted impacts of nanoparticles on plant nutrient absorption and soil microbial communities. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Tan, J.; Liu, F.; Wu, J. The mechanism of promoting rhizosphere nutrient turnover for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi attributes to recruited functional bacterial assembly. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 2335–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shu, K.; Zhang, L.; Si, Y. Effects of silver nanoparticles on soil microbial communities and bacterial nitrification in suburban vegetable soils. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plokhovska, S.; García-Villaraco, A.; Lucas, J. A. , Gutierrez-Mañero, F. J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Silver nanoparticles coated with metabolites of Pseudomonas sp. N5.12 inhibit bacterial pathogens and fungal phytopathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plokhovska, S.; Fuente-González, E.; Gutierrez-Albanchez, E.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F.-J.; Ramos-Solano, B. AgNPs biosynthesized from Pseudomonas Z9.3 metabolites as antimicrobial agents against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1565689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J. A.; Garcia-Villaraco, A.; Montero-Palmero, M. B.; Montalban, B.; Ramos-Solano, B.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F. J. Physiological and genetic modifications induced by Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in tomato plants under moderate water stress. Biology 2023, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rivilla, H.; Garcia-Villaraco, A.; Ramos-Solano, B.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F. J.; Lucas, J. A. Bioeffectors as biotechnological tools to boost plant innate immunity: signal transduction pathways involved. Plants 2020, 9, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. M.; Spitzer, N. Silver nanoparticles induce formation of multi-protein aggregates that contain cadherin but do not colocalize with nanoparticles. Toxicol. In Vitro 2024, 98, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, S.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, V. Uptake, translocation, transformation and physiological effects of nanoparticles in plants. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 1579–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lombi, E.; Zhao, F-J.; Kopittke, P. M. Nanotechnology: A new opportunity in plant sciences. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Peralta-Videa, J. R.; Su, Z.; Hong, J.; Zhao, L. Biological effects of AgNPs on crop plants: environmental implications and agricultural applications. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xiang, S.; Lv, X.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Ran, M.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, X.; Jin, Y.; Sun, X. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles inhibit Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci by directly destroying bacteria and inducing plant resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. Phytopathol. Res. 2022, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Raza, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Ajmal, M.; Mehak, A.; Fatima, N.; Abasi, F.; Sathiya Seelan, J.S.; Raja, N.I.; Yongchao, B.; Zain, M.; Javaid, R.A.; Maimaiti, Y. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles enhanced wheat resistance to Bipolaris sorokiniana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessling, J. W.; Yanyan, S.; Kühl, M.; Ellegaard, M. Frustule photonics and light harvesting strategies in diatoms. In Diatom Morphogenesis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdallah, N. M.; Hasan, Md. M. Plant-based green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its effective role in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5631–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Ahmed, S.; Abbasi, A.; Hamad, N. A.; Ali, H. M.; Khan, M. T.; Haq, I. U.; Zaman, Q. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles: A novel approach for the enhanced growth and yield of tomato against early blight disease. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Malondialdehyde: Facts and Artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonathan, K.; Mann, R.; Mahbub, K. R.; Gunawan, C. The impact of silver nanoparticles on microbial communities and antibiotic resistance determinants in the environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwani, M.; Chakdar, H.; Srivastava, A.; Pabbi, S.; Shukla, P. Effects of nanofertilizers on soil and plant-associated microbial communities: Emerging trends and perspectives. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, D. B.; Gagnon, V.; Button, M.; Farooq, A. J.; Patch, D. J.; Wallace, S. J.; Koch, I.; O’Carroll, D. M.; Weber, K. P. Silver nanomaterials released from commercial textiles have minimal impacts on soil microbial communities at environmentally relevant concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Hunting, E.; Wouters, M.; Peijnenburg, W.; Vijver, M. Silver nanoparticles, ions, and shape governing soil microbial functional diversity: Nano shapes micro. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, C. F.; Storey, S.; Clipson, N.; Doyle, E. Soil microbial community responses to contamination with silver, aluminium oxide and silicon dioxide nanoparticles. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Schlaeppi, K.; Spaepen, S.; Themaat, E. V. L. van; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; Novello, G.; Bona, E.; Gorrasi, S.; Gamalero, E. Impact of plant-beneficial bacterial inocula on the resident bacteriome: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, J. A.; Spor, A.; Koren, O.; Jin, Z.; Tringe, S. G.; Dangl, J. L.; Buckler, E. S.; Ley, R. E. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 6548–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porra, R. J.; Thompson, W. A.; Kriedemann, P. E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Bioenerg. 1989, 976, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148C, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Kumar, S.; Tripathi, Y. N.; Upadhyay, R. S. Bacillus subtilis- and Pseudomonas fluorescens-mediated systemic resistance in tomato against sclerotium rolfsii and study of physio-chemical alterations. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Fan, J.; Chen, K.; Amombo, E.; Chen, L.; Fu, J. Effects of ethylene on photosystem II and antioxidant enzyme activity in Bermuda grass under low temperature. Photosynth. Res. 2016, 128, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcı́a-Limones, C.; Hervás, A.; Navas-Cortés, J. A.; Jiménez-Dı́az, R. M.; Tena, M. Induction of an antioxidant enzyme system and other oxidative stress markers associated with compatible and incompatible interactions between chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.ciceris. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 61, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B. J.; Chang, S. K. C. A comparative study on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of legumes as affected by extraction solvents. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, s159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, J. L.; Mills, A. L. Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community-level sole-carbon-source utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Parada, A. E.; Needham, D. M.; Fuhrman, J. A. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quince, C.; Lanzen, A.; Davenport, R. J.; Turnbaugh, P. J. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T. D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T. J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J., White, T. J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.-M.; Lu, T.-P.; Tsai, M.-H.; Lai, L.-C.; Chuang, E. Y. EasyMAP: A user-friendly online platform for analyzing 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing data. New Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarenkov, K.; Zirk, A.; Piirmann, T.; Pöhönen, R.; Ivanov, F.; Nilsson, R.H.; Kõljalg, U. UNITE QIIME release for Fungi. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N. A.; Kaehler, B. D.; Rideout, J. R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G. A.; Caporaso, J. G. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).